Key Drivers of Soil Microbial Community Composition: From Foundational Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article synthesizes current research on the complex factors governing soil microbial community composition, a field with profound implications for ecosystem health and biomedical discovery.

Key Drivers of Soil Microbial Community Composition: From Foundational Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the complex factors governing soil microbial community composition, a field with profound implications for ecosystem health and biomedical discovery. We explore the hierarchical influence of soil properties, from energy sources and environmental stressors to plant interactions. The content details advanced methodological approaches for community profiling, analyzes common disturbances like drought and monoculture, and presents comparative validation of agricultural management practices. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights how understanding soil microbiomes can inform strategies for ecosystem restoration and provide novel insights into microbial ecology relevant to human health.

The Hierarchical Framework of Soil Microbiome Drivers: Energy, Stress, and Host Interactions

The soil microbiome, a complex assembly of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and other microorganisms, is a fundamental component of terrestrial ecosystems, driving critical processes from organic matter decomposition to nutrient cycling [1] [2]. Understanding the factors that shape the structure and function of these communities remains a central challenge in microbial ecology. While numerous studies have identified correlations between various environmental attributes and microbial composition, the incredible complexity of soil systems, with thousands of taxa coexisting in microhabitats separated by micrometers, makes identifying causative relationships particularly difficult [1]. This complexity is further compounded by the interplay of spatial and temporal scales, which influences the relative importance of different drivers.

To address this challenge, we propose a hierarchical model that ranks environmental and edaphic attributes based on their importance to the fundamental physiological needs of soil microorganisms. This framework moves beyond simple correlation-based analyses to provide a mechanistic understanding of community assembly, enabling more accurate predictions of microbial responses to environmental change and more targeted manipulations for agricultural and ecosystem management. By systematically organizing drivers according to ecological principles, this model offers researchers a structured approach for designing experiments, interpreting data, and building predictive models of soil microbial ecology.

The Hierarchical Framework for Microbial Drivers

The proposed hierarchical model ranks drivers based on their fundamental importance to microbial survival, growth, and function, while simultaneously accounting for the influence of spatial and temporal scales. This framework recognizes that while all factors can influence microbial communities, they do not contribute equally to community assembly processes.

Theoretical Foundation and Ranking Principles

The model organizes drivers into four primary tiers based on microbial physiological requirements:

Tier 1: Energy Supply - Factors that supply energy, including organic carbon quality/quantity and electron acceptors (especially oxygen), represent the most fundamental determinants of microbial presence and activity [1]. These resources directly fuel metabolic processes and establish the basic potential for microbial growth in a given habitat.

Tier 2: Environmental Effectors - Abiotic conditions that create the physical and chemical context for microbial life, including pH, salt concentration, drought stress, and toxic chemicals [1]. These factors determine whether a habitat is suitable for microbial persistence by imposing physiological constraints on survival.

Tier 3: Macro-organism Associations - Biological interactions with plants (including their seasonality), animals, and soil fauna that modify the soil environment and provide specialized niches [1]. These associations often mediate resource availability and microhabitat formation.

Tier 4: Nutrients - Essential elements required for biomass synthesis, with nitrogen and phosphorus typically being most critical, followed by other micronutrients and metals [1]. While essential, these factors often become limiting only after energy and habitat requirements are satisfied.

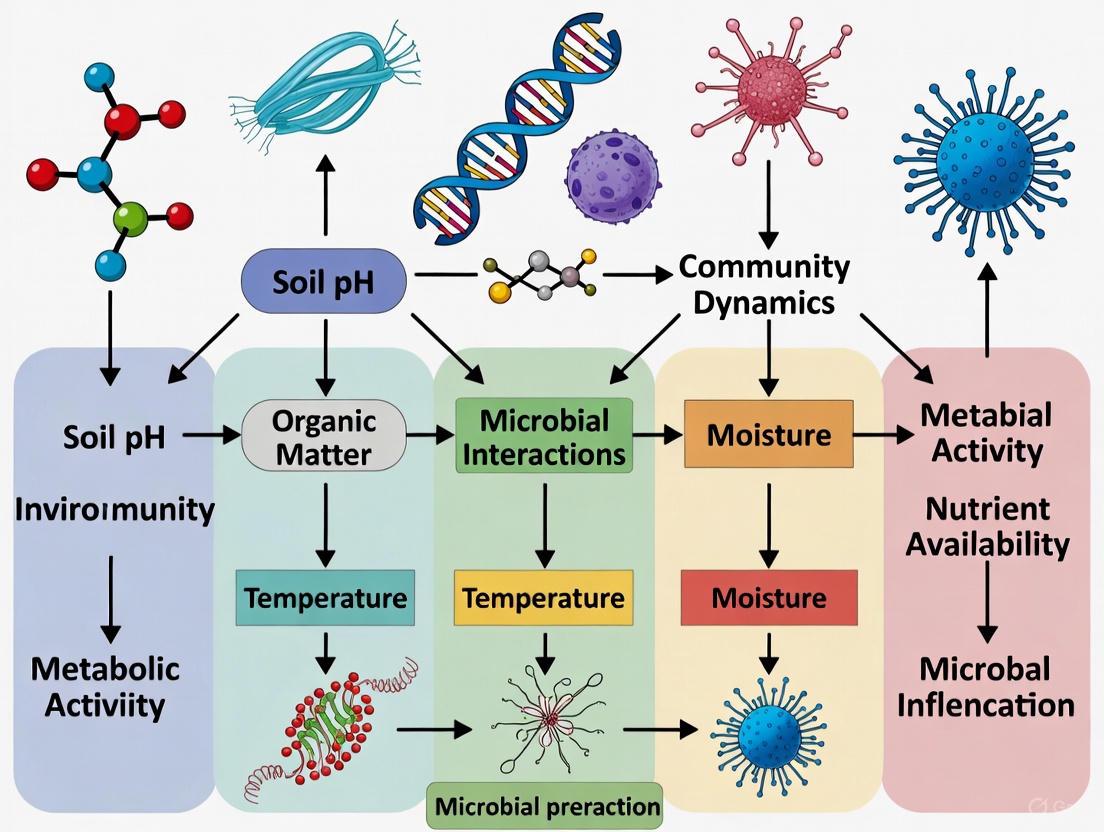

This hierarchy is visually summarized in the following diagram, which illustrates both the ranking and the interconnections between driver categories:

The Dimension of Scale in Driver Hierarchy

The relevance of specific drivers varies considerably across spatial and temporal scales, creating a dynamic context for the hierarchical model. At larger spatial scales (field to regional), factors influencing soil formation—parent material, climate, vegetation, and topography—create variation in soil type and physicochemical properties that fundamentally shape microbial composition [1]. In contrast, at smaller spatial scales (aggregate to millimeter), distinct environments vary in terms of organic matter quality, pH, pore geometry, and redox potential, creating microhabitats that support different microbial communities [1].

Temporal scale similarly influences driver importance. Persistent populations that have long adapted to soil conditions form a stable community core, while dynamic populations respond to seasonal fluctuations, resource inputs, or disturbance events [1]. This temporal dynamic was demonstrated in a three-year biodiversity experiment where microbial response to plant composition strengthened over time, while response to plant species richness weakened [3].

Quantitative Evidence Supporting the Hierarchy

Relative Contributions of Different Driver Classes

Research across diverse ecosystems has quantified the relative importance of the hierarchical driver categories. A comprehensive study of tropical soils found that bacterial community composition had a strong relationship to edaphic factors (70-80% similarity within communities), while archaeal and fungal communities showed weaker relationships (40-50% similarity) [4]. More specifically, the study identified distinct sets of edaphic factors that best explained variation for each microbial domain:

Table 1: Edaphic Factors Explaining Microbial Community Variation

| Microbial Group | Most Explanatory Edaphic Factors | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Total carbon, sodium, magnesium, zinc | Strongest correlation |

| Fungi | Sodium, magnesium, phosphorus, boron, C/N ratio | Moderate correlation |

| Archaea | Set 1: Sulfur, sodium, ammonium-NSet 2: Clay, potassium, ammonium-N, nitrate-N | Weakest correlation |

These findings demonstrate the tiered hierarchy in action, with carbon resources (Tier 1) featuring prominently for bacteria, while nutrients (Tier 4) and effectors like sodium (Tier 2) appear across domains but with varying importance.

Precipitation as a Cross-Cutting Environmental Effector

As a key environmental effector (Tier 2), precipitation regimes demonstrate how hierarchical drivers operate across ecosystems. A three-year biodiversity experiment found that precipitation manipulations (50% vs. 150% of ambient) drove significant differentiation in all microbial groups studied [3]. The direction of response, however, varied by functional group: oomycete and bacterial diversity increased with 150% precipitation, while arbuscular mycorrhizal and saprotroph fungal diversity decreased [3].

The influence of precipitation operates across temporal scales, with long-term patterns (30+ years) creating legacy effects on soil physiology and microbial assemblages [2]. Forests exposed to higher precipitation over decades showed positive correlations between total organic carbon, total nitrogen, extracellular enzyme activities, and phospholipid fatty acids content, though microbial diversity paradoxically decreased [2]. This demonstrates how a Tier 2 environmental effector (precipitation) can influence Tier 1 factors (energy resources like organic carbon), creating complex interactions across hierarchical levels.

Table 2: Microbial Responses to Precipitation Manipulation

| Microbial Group | Response to Increased Precipitation | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Oomycetes | Diversity increased | 3-year biodiversity experiment [3] |

| Bacteria | Diversity increased | 3-year biodiversity experiment [3] |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi | Diversity decreased | 3-year biodiversity experiment [3] |

| Saprotroph Fungi | Diversity decreased | 3-year biodiversity experiment [3] |

| Overall Microbial Biomass | Positive correlation with TOC, TN, EEAs, PLFA | 30-year precipitation gradient [2] |

| Microbial Diversity | Negative correlation with precipitation | 30-year precipitation gradient [2] |

Plant Associations as Biological Drivers

The influence of plant associations (Tier 3) demonstrates how biological interactions modify microbial communities. Research has shown that plant species richness can generate increases in microbial diversity, with different plant species selecting for distinct microbiomes through root architecture, exudates, and other functional traits [3]. This relationship, however, is time-dependent, as demonstrated by experiments showing that microbial differentiation in response to plant family and species composition strengthened after three growing seasons compared to responses after the first year [3].

The critical importance of an intact soil microbiome for plant establishment was further demonstrated through gamma-irradiation experiments, which found that microbiome dysbiosis severely reduced canola shoot and root growth, despite preserved soil physicochemical properties [5]. This highlights the reciprocal nature of plant-microbe interactions and their placement in Tier 3 of the hierarchy.

Methodologies for Studying the Driver Hierarchy

Community Profiling and Typing Approaches

Characterizing microbial communities across different hierarchical drivers requires sophisticated profiling and typing methodologies. Common approaches include:

Amplicon Sequencing: Targeted amplification of taxonomic marker genes (16S rRNA for prokaryotes, ITS for fungi) followed by high-throughput sequencing [4] [6]. This approach provides detailed compositional data but limited functional information.

Phospholipid Fatty Acid Analysis (PLFA): Extraction and analysis of membrane phospholipids to characterize functional groups within microbial communities [7]. This method provides information on viable biomass and broad functional groups but limited taxonomic resolution.

Community Typing Techniques: Statistical approaches for identifying distinct microbial communities, including:

- Unsupervised clustering methods (hierarchical clustering, K-means)

- Dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, PCoA)

- Model-based approaches (Dirichlet Multinomial Mixtures) [8]

The experimental workflow for implementing these techniques typically follows a structured pathway from sampling through data analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementation of these methodologies requires specific research reagents and tools, particularly for nucleic acid-based approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Soil Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil) | Efficient lysis of diverse microbial cells and purification of inhibitor-free DNA | Standardized extraction from soil matrices [5] |

| PCR Primers (515F/806R, ITS1F/ITS4) | Target-specific amplification of taxonomic marker genes | 16S rRNA amplification for bacterial communities; ITS for fungal communities [4] |

| Illumina Sequencing Chemistry | High-throughput sequencing of amplicon libraries | MiSeq 600 cycle v3 kits for community profiling [6] |

| Quantitative PCR Reagents | Absolute quantification of specific taxonomic or functional groups | Pathogen abundance (e.g., Verticillium dahliae, pathogenic Streptomyces) [6] |

| PLFA Standards & Solvents | Extraction and identification of membrane phospholipids | Microbial biomass estimation and functional group characterization [7] |

| GSK-843 | GSK-843, MF:C19H15N5S2, MW:377.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KeIKK5 | KeIKK5, MF:C20H21N3O3, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The hierarchical model for soil microbial drivers has significant implications for both basic research and applied management. By providing a structured framework for understanding microbial community assembly, it enables more targeted manipulations of soil ecosystems for agricultural productivity, conservation, and climate change mitigation.

In agricultural contexts, understanding driver hierarchies can inform management practices that optimize crop production through microbiome management [6]. The recognition that microbial communities are shaped by identifiable hierarchies of factors provides a roadmap for designing cropping systems, rotation strategies, and soil amendments that foster beneficial microbial assemblages.

Under climate change scenarios, the hierarchical model helps predict how microbial communities—and the functions they mediate—may respond to altered precipitation patterns, temperature regimes, and atmospheric composition [7] [2]. Research in mountain ecosystems has demonstrated how microbial community composition and associated nutrient cycling processes vary with altitude and aspect, providing insights into how these systems may respond to global warming [7].

Future research should focus on quantifying interaction effects between driver tiers, incorporating temporal dynamics more explicitly into the hierarchy, and linking specific driver combinations to microbial functional traits and ecosystem processes. The integration of multi-omics approaches—combining metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics—will be particularly valuable for moving beyond correlation to mechanistic understanding [2].

The hierarchical model for soil microbial drivers presented here offers a structured framework for understanding the complex interplay of factors that shape soil microbial communities. By ranking drivers according to their fundamental importance to microbial physiology and acknowledging the modifying influence of spatial and temporal scales, this approach provides researchers with a powerful tool for designing experiments, interpreting data, and predicting microbial responses to environmental change.

The evidence from diverse studies consistently supports the proposed hierarchy, with energy resources (Tier 1) and environmental effectors (Tier 2) generally exerting stronger influences than biological associations (Tier 3) and nutrients (Tier 4), though with important context-dependent variations. As research in soil microbial ecology continues to advance, this hierarchical framework provides a foundation for building more predictive models of microbial community dynamics and developing more targeted approaches for managing soil ecosystems in a changing world.

In soil and other environments, microbial community composition and function are governed by the availability of two fundamental resources: organic carbon for energy and electron acceptors for respiration. The interplay between these resources dictates the metabolic pathways employed by microorganisms, ultimately shaping the ecosystem's biogeochemical functioning. This review examines the primacy of organic carbon and oxygen availability in regulating microbial energy dynamics, with a specific focus on how the limitation of terminal electron acceptors (TEAs) influences community structure and function in soil environments. Understanding these relationships is crucial for predicting ecosystem responses to environmental changes, such as deoxygenation and organic matter input, and for harnessing microbial capabilities in bioremediation and bioenergy applications.

Core Principles of Energy and Electron Flow

Organic Carbon as the Energy Source

Organic carbon (Corg) compounds, derived from plant exudates, decaying biomass, or anthropogenic inputs, serve as the primary energy source for heterotrophic microorganisms in soil. Through catabolic reactions, microbes oxidize these compounds, generating electrons that are transferred through an electron transport chain to a terminal electron acceptor. The type of Corg—whether labile (e.g., simple sugars, organic acids) or recalcitrant (e.g., humic substances, lignin)—significantly influences the rate of energy generation and the microbial taxa capable of its utilization [9].

The Electron Acceptor Hierarchy

Microorganisms utilize electron acceptors in a sequence based on the energy yield of the corresponding redox reaction, following the thermodynamic hierarchy of O2 > NO3- > Mn(IV) > Fe(III) > SO42- > CO2 [9]. Oxygen (O2), as the most energetically favorable TEA, supports aerobic respiration. When oxygen is depleted, anaerobic microorganisms sequentially utilize alternative TEAs. The availability of these acceptors is a critical factor determining microbial community composition and metabolic output, including the ratio of carbon dioxide (CO2) to methane (CH4) released [10].

Table 1: Energy Yields of Key Respiratory Pathways

| Respiratory Pathway | Terminal Electron Acceptor | Relative Energy Yield (per glucose) | Key Microbial Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Respiration | O2 | High (Highest) | Diverse aerobes |

| Denitrification | NO3- → N2 | High (~99% of aerobic) | Pseudomonas, Paracoccus |

| Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium (DNRA) | NO3- → NH4+ | Medium (~64% of aerobic) | Shewanella, Geobacter |

| Metal Reduction | Fe(III) → Fe(II), Mn(IV) → Mn(II) | Medium | Shewanella, Geobacter |

| Sulfate Reduction | SO42- → H2S | Low | Desulfovibrio |

| Methanogenesis | CO2 → CH4 | Low (Lowest) | Methanobacterium, Methanoregula |

Microbial Community Composition and Metabolic Adaptations

Community Shifts Along Oxygen Gradients

The transition from oxic to anoxic conditions creates distinct ecological niches, leading to profound shifts in microbial community composition. In surface layers of peatland soils, communities are dominated by Acidobacteriota, Actinomycetota, and Proteobacteria, which include many aerobic chemoorganoheterotrophs [10]. In contrast, deeper anoxic layers show a predominance of Thermoproteota (archaea), Chloroflexota, and Verrucomicrobiota, which are specialized for anaerobic metabolisms [10]. This stratification is a direct response to TEA availability and organic matter quality.

The Role of Exoelectrogens and Interspecies Interactions

A key functional group in anaerobic soils are exoelectrogens—microorganisms capable of Extracellular Electron Transfer (EET). Model organisms like Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and Geobacter sulfurreducens can transfer electrons derived from Corg oxidation directly to insoluble extracellular acceptors such as Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxides, or even to electrodes in microbial fuel cells (MFCs) [11] [12]. This capability allows them to access electron acceptors that are inaccessible to other microbes.

The introduction of an exogenous exoelectrogen like S. oneidensis MR-1 into an iron mine soil community can significantly alter the population dynamics, enhancing the electrochemical activity of the entire consortium [11]. In one study, co-culture with MR-1 increased the relative abundance of Pelobacteraceae while decreasing Rhodocyclaceae, resulting in a higher maximum power density (195 ± 8 mW/m²) compared to the native soil community alone (175 ± 7 mW/m²) [11]. This demonstrates how specific microbial inoculations can be used to steer community composition and function towards desired outcomes, such as enhanced power generation or bioremediation.

Experimental Evidence and Data Synthesis

Quantitative data from controlled experiments provides critical evidence for the interactions between carbon, electron acceptors, and microbial communities. The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Microbial Community and Electron Acceptor Studies

| Study System / Condition | Key Measured Variable | Result / Value | Implication for Community/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFC: Iron mine soil + S. oneidensis MR-1 (Co-culture) | Maximum Power Density | 195 ± 8 mW/m² | Interspecies interaction enhances electroactivity [11] |

| MFC: Iron mine soil alone | Maximum Power Density | 175 ± 7 mW/m² | Baseline performance of native community [11] |

| MFC: S. oneidensis MR-1 alone | Maximum Power Density | 88 ± 8 mW/m² | Pure culture less effective than mixed community [11] |

| S. baltica culture (Suboxic, High NO3-) | C:N Loss Ratio (Denitrification) | ~2.0 | Nitrate availability compensates for O2 lack; N loss [9] |

| S. baltica culture (Suboxic, Low NO3-) | C:N Loss Ratio (DNRA) | ~5.5 | Alternative anaerobic pathway; N retention [9] |

| SPRUCE Peatland (Depth: 100-175 cm) | Read Recruitment to MAGs | 67.4 - 67.7% | High representation of deep peat anaerobes in genomic library [10] |

Methodologies for Investigating Microbial EET and Community Dynamics

Enrichment and Analysis of Electroactive Biofilms

Protocol: Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC) Setup for Soil Biofilms [11]

- Reactor Configuration: Construct two-chambered electrochemical fuel cells, typically from glass, with a proton exchange membrane (e.g., Nafion-117) separating the anode and cathode chambers.

- Electrode Preparation: Use carbon paper or cloth (e.g., 3 cm x 3 cm) as electrodes. Clean them via sequential ultrasonic cleaning in acetone and deionized water.

- Inoculation and Medium: Inoculate the anode chamber with the soil sample or microbial culture in a defined anaerobic medium (e.g., DM medium). The cathode chamber contains a catholyte, often 50 mmol/L potassium ferricyanide in a phosphate buffer.

- Operation: Connect the electrodes via an external resistor (e.g., 1000 Ω) and operate the MFC at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C). Anaerobic conditions in the anode are maintained by sparging with nitrogen gas.

- Data Collection: Monitor voltage across the resistor daily using a data acquisition card. Calculate current and power density using Ohm's law. Perform electrochemical analyses like cyclic voltammetry (e.g., at 10 mV/s) to characterize electron transfer mechanisms.

- Post-experiment Analysis: After operation, analyze biofilms on the anode using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for morphology and 16S rRNA gene sequencing (e.g., Illumina HiSeq of the V4 region with primers 515F/806R) for community composition.

Investigating Electron Acceptor Limitations in Culture

Protocol: Continuous Culture with Oxygen and Nitrate Gradients [9]

- Culture System: Establish a continuous culture system with a facultative anaerobic bacterium (e.g., Shewanella baltica) and a defined labile carbon source (e.g., glucose).

- Variable Manipulation: Test a gradient of oxygen concentrations, from fully oxic to suboxic (<5 µmol Lâ»Â¹). Cross this with variations in the availability of alternative electron acceptors, specifically high and low concentrations of inorganic nitrogen (nitrate/nitrite) relative to the carbon source.

- Monitoring and Sampling: Continuously monitor and document dissolved oxygen. Regularly sample the culture to measure key parameters.

- Key Analyses:

- Carbon and Nitrogen Uptake/Loss: Quantify dissolved organic carbon (DOC) uptake, particulate organic carbon (POC) production, and nitrogen loss to establish C:N loss ratios, which indicate the dominant respiratory pathway (e.g., denitrification vs. DNRA).

- Growth Efficiency: Calculate Bacterial Growth Efficiency (BGE) as the ratio of bacterial production to bacterial carbon demand.

Diagram 1: Pathway determination by resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Investigating Electron Transfer and Microbial Communities

| Category / Item | Specific Example(s) | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Electroactive Microbes | Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, Geobacter sulfurreducens | Model exoelectrogens for studying EET mechanisms, co-culture experiments, and bioelectrochemical system inoculation [11] [12]. |

| Bioelectrochemical Systems | Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC), Microbial Electrolysis Cell (MEC) | Apparatus to cultivate electroactive biofilms, study EET, and apply it for power generation or remediation of heavy metals [12]. |

| Electrode Materials | Carbon paper, carbon cloth; CNF/Mn—Co, rGO/PANI-modified anodes | Serve as solid electron acceptors/donors. Modified anodes enhance conductivity and EET rate, improving system performance and microbial tolerance to toxins [11] [12]. |

| Electron Mediators & Shuttles | Humic acids, Biochar | Act as redox-active molecules that can shuttle electrons between microbes and distant electron acceptors, accelerating EET rates [12]. |

| Conductive Minerals | Pyrite (FeS₂), Magnetite (Fe₃O₄), other Iron Oxides | Serve as insoluble electron acceptors in anaerobic respiration. Can participate in abiotic-biotic coupled reduction of contaminants like Sb(V) and Cr(VI) [12]. |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Microbial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., SunShineBio) | Extract and purify metagenomic DNA from complex environmental samples like biofilms on anodes for subsequent 16S rRNA sequencing [11]. |

| Sequencing Primers | 515F (5'-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3'), 806R (5'-GGACTACVSGGGTATCTAAT-3') | Target the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene for high-throughput Illumina sequencing and community analysis [11]. |

| 10-Deacetylpaclitaxel 7-Xyloside | 10-Deacetylpaclitaxel 7-Xyloside, MF:C50H57NO17, MW:944.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NSC23925 | NSC23925, CAS:1977557-97-3, MF:C65H84N10O11, MW:1181.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Soil Research and Bioremediation

The principles governing energy and electron acceptors directly influence strategies for managing soil microbial communities. The ability of exoelectrogens to reduce heavy metals via EET is being harnessed for bioremediation. For instance, coupled systems like constructed wetlands-MFCs (CW-MFCs) have demonstrated removal efficiencies exceeding 90% for Cu, Pb, Zn, and Cd [12]. The manipulation of electron acceptor availability, such as by adding organic carbon to drive the reduction of contaminants like Cr(VI), represents a powerful approach to in situ remediation.

Furthermore, the resilience of peatland microbial communities to warming, as observed in the SPRUCE experiment, suggests that the metabolic versatility of these communities allows them to adapt their activity without drastic taxonomic shifts [10]. This finding is crucial for predictive models of soil carbon cycling under climate change.

Diagram 2: Conceptual research framework.

The dynamics of organic carbon and electron acceptors are foundational to understanding and predicting the structure and function of soil microbial communities. The primacy of oxygen availability, and the subsequent cascade of alternative electron accepting processes when oxygen is depleted, creates a complex metabolic landscape that shapes community composition. Advances in genomic techniques and bioelectrochemical systems have illuminated the critical role of specialized microbes, such as exoelectrogens, and their interspecies interactions. Integrating these principles into soil research provides a robust framework for addressing pressing environmental challenges, from climate change feedbacks to the development of novel bioremediation technologies. Future work should focus on elucidating the EET mechanisms of non-model electroactive microorganisms and translating laboratory findings into predictable field-scale applications.

{#context} This whitepaper examines three critical environmental stressors—pH, salinity, and drought intensity—as defining factors shaping soil microbial community composition, structure, and function. The content is framed within the context of a broader thesis on soil research, providing technical depth and methodological insights for researchers and scientists. {#context}

Soil microbial communities are fundamental drivers of ecosystem functioning, regulating processes from nutrient cycling to plant health. Understanding the forces that shape these communities is a primary objective in microbial ecology. Among the most influential factors are the abiotic environmental stressors of soil pH, salinity, and drought intensity. These stressors act as powerful filters, selecting for microbial taxa with specific functional traits and ultimately determining community assembly and resilience [13] [14]. This technical guide synthesizes current research to elucidate the mechanisms through which these stressors exert their influence, providing a foundational resource for ongoing soil research and the development of microbial management strategies.

Drought Intensity

Microbial Response Mechanisms and Community Shifts

Drought stress, characterized by prolonged water deficit, alters the soil physical habitat and imposes significant osmotic stress on microorganisms. The primary microbial survival strategies involve the reallocation of carbon resources towards the production of osmolytes (e.g., trehalose, ectoine, and proline) to maintain cellular turgor pressure, the formation of protective biofilms, and a potential shift to dormancy [15] [13]. These mechanisms are energetically expensive, often leading to trade-offs where resources are diverted from growth and enzyme production to stress tolerance [15].

These physiological responses scale to the community level, causing measurable shifts in composition. Actinobacteria and other Gram-positive bacteria are frequently reported to be more resistant to drought due to their thicker, more rigid cell walls, often becoming enriched in dry soils [16] [13]. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria like some Pseudomonadota are often more sensitive and may decline in relative abundance [16]. The fungal response is complex; some studies indicate that fungi, with their hyphal networks that can access water in small soil pores and adaptations like melanized cell walls, exhibit greater resistance to drought than bacteria [17] [18]. However, this is context-dependent, with other studies showing strong fungal responses to extreme events [17].

Table 1: Microbial Functional Traits and Trade-offs Under Drought Stress

| Functional Trait | Representative Indicators | Response to Drought | Resource Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Tolerance (S) | Osmolyte production genes; Trehalose synthesis | Increases [15] | High carbon cost |

| Resource Acquisition (A) | Extracellular enzyme activity (e.g., phosphatases, β-glucosidase) | Decreases [19] [13] | Reduced nutrient mining |

| High Yield (Y) | Growth rate; Carbon use efficiency | Decreases [15] | Energy diverted to maintenance |

Legacy Effects and Ecosystem Implications

A critical concept in drought microbiology is the legacy effect, where past exposure to water stress alters how soil microbiota respond to future droughts. Soils with a history of low precipitation harbor microbial communities that are functionally adapted to dry conditions, which can persist for months and even mitigate the negative physiological effects of subsequent droughts on plants [16]. Research on a native wild grass (Tripsacum dactyloides) showed that soil microbiota with a low-precipitation legacy altered the expression of plant genes related to transpiration and intrinsic water-use efficiency, thereby enhancing plant drought tolerance [16]. However, this protective effect was not observed for maize, indicating plant species-specific outcomes [16].

The intensity of drought is a key determinant of its long-term impact. Mild droughts may allow microbial communities to return to their baseline composition after rewetting. In contrast, severe or extreme droughts can cause shifts in bacterial and fungal community composition that persist for months after the drought ends, indicating a potential for irreversible change [20] [17]. These legacy effects can disrupt key ecosystem functions, including the cycling of carbon and nitrogen, with significant implications for soil fertility and overall ecosystem stability [19] [18].

Diagram 1: Microbial Drought Response Pathway. This flowchart illustrates the cascade from drought stress to ecosystem-level outcomes, highlighting the role of physiological and community-level microbial adaptations.

Soil Salinity

Compositional and Functional Adaptations

Soil salinity imposes both osmotic stress, which dehydrates microbial cells, and ionic stress, which can disrupt enzyme function and be toxic at high concentrations. Unlike drought, which can show variable diversity responses, salinity is a dominant filter and a key driver of consistent shifts in microbial community composition, significantly reducing microbial activity and potential enzyme function [14]. While bacterial richness may not always show a significant decline, the community structure undergoes a profound reorganization.

Microbial communities in saline soils exhibit distinct co-occurrence network patterns, showing stronger dependencies between species, which suggests a shift towards more specialized and interdependent communities as a coping mechanism [14]. Furthermore, microbial groups capable of producing compatible solutes (e.g., glycine betaine) and maintaining ion homeostasis are selected for. Over time, this leads to the enrichment of salt-tolerant microbial lineages, resulting in a community with a distinct functional potential adapted to the saline environment [14].

Table 2: Experimental Overview of Salinity and Drought Studies

| Stress Factor | Experimental Design | Key Measured Parameters | Major Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity | Field survey of coastal agro-ecosystems; soils categorized as non-, mild-, and severe-salinity [14] | Soil EC, pH, SOC; Bacterial 16S sequencing; Microbial activity via microcalorimetry | Salinity is a major driver of community composition; Labile C addition alleviates salt restriction on microbial activity. |

| Drought Intensity | Outdoor grassland mesocosm experiment with increasing drought intensity levels [20] | Bacterial & fungal community composition (sequencing); Potential extracellular enzyme activity | Severe drought shifts community composition with effects persisting 2 months after rewetting; Plant community traits mediate the response. |

| Drought & Resources | Field manipulation of drought and carbon availability across land uses [15] | Metagenomics; Microbial biomass C; Respiration; Stress tolerance bioassays | Drought increases microbial allocation to stress tolerance; Added carbon enables greater expression of stress tolerance under drought. |

Mitigation Through Carbon Amendment

A critical insight from recent research is that the negative effects of salinity on microbial activity are not solely due to toxicity but are also linked to resource limitation, particularly carbon. Sparse plant growth in saline soils leads to low organic matter inputs, further constraining microbial energy supplies [14]. Microcalorimetric studies demonstrate that while salinity prolongs the lag time of microbial communities (delaying the onset of activity), the addition of labile organic amendments like glucose can greatly alleviate salt restrictions [14]. Once activated with sufficient carbon, the microbial communities in saline soils can exhibit high growth rates, revealing a significant potential for restored ecological function with appropriate management.

Research Reagents and Methodologies

This section details key reagents, tools, and methodologies essential for investigating microbial community responses to environmental stressors, providing a toolkit for experimental design.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

| Reagent / Method | Primary Function / Rationale | Technical Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) | Standardized extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from diverse soil types, critical for downstream sequencing. | Used in both salinity [14] and drought [18] studies to ensure comparative metagenomic and amplicon analysis. |

| 515F/806R Primers | Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene V4 region for profiling bacterial and archaeal community composition. | A standard for bacterial diversity studies; used in salinity [14] and drought [18] research. |

| ITS7/ITS4 Primers | Amplification of the fungal ITS2 region for fungal community profiling. | Essential for parallel analysis of the fungal kingdom, as in clonal oak drought studies [18]. |

| Isothermal Microcalorimetry | Direct, continuous measurement of microbial metabolic heat output in soil samples. | Used to assess microbial growth kinetics and response to glucose amendment in saline soils [14]. |

| Metagenomic & Metatranscriptomic Sequencing | Unbiased analysis of the functional potential (genes) and actual activity (mRNA) of the entire microbial community. | Key for identifying drought-enriched traits (e.g., osmolyte synthesis) and legacy effects [16] [15]. |

| Hot Water/Cold Water Extraction | Quantification of labile (easily decomposable) and bioavailable soil organic carbon (CWC) and nitrogen (HWC, HWN). | Used to link soil carbon pools to microbial activity and drought response [18]. |

Representative Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Drought Legacy on Soil Microbiota

The following workflow, derived from a 2025 Nature Microbiology study, provides a robust methodology for investigating precipitation legacy effects on soil microbial communities and their functional consequences for plants [16].

- Site Selection and Soil Collection: Identify a steep natural precipitation gradient. Collect soil cores from multiple sites along the gradient, ensuring representation of low- and high-precipitation histories. Record site characteristics (e.g., mean annual precipitation, temperature, vegetation type).

- Conditioning Phase (Experimental Perturbation): Subject collected soils to a controlled factorial experiment.

- Factors:

Precipitation Legacy(field condition) xConditioning Watering(drought vs. well-watered) xHost(unplanted vs. planted with a model grass). - Duration: Conduct over a significant period (e.g., 5 months) to allow for community adjustment.

- Factors:

- Molecular Analysis:

- DNA Extraction: Use a standardized kit (e.g., PowerSoil Kit) on all samples.

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: Sequence all samples to assess taxonomic composition and functional gene potential. Assemble contigs and annotate genes using databases like KEGG and GO.

- Variant Analysis: Map reads to reference genomes of key bacterial taxa to identify precipitation-associated genetic variants.

- Plant Response Assay:

- Plant Growth: Grow target plant species (e.g., a native grass and a crop like maize) in the conditioned soils.

- Drought Challenge: Expose plants to an acute drought stress.

- Physiological Monitoring: Measure plant physiology (e.g., water-use efficiency, transpiration rate).

- RNA Sequencing: Perform RNA-Seq on plant roots to identify differentially expressed genes in response to soil microbiota history.

- Data Integration: Correlate microbial community and metagenomic data with plant physiological and transcriptomic outcomes to establish mechanistic links.

Diagram 2: Legacy Effect Study Workflow. This diagram outlines the key phases in an experimental investigation of microbial legacy effects, from soil collection through to data integration.

The stressors of drought intensity, salinity, and pH are powerful determinants of soil microbial community structure and function. Drought triggers trade-offs where microbes allocate carbon to survival over growth, with consequences for nutrient cycling. The intensity of drought and the historical legacy of water stress are critical in determining whether changes are transient or persistent. Salinity acts as a dominant filter, restructuring communities and suppressing activity, though this can be mitigated by carbon addition. Understanding the distinct and interactive mechanisms of these stressors provides a predictive framework for managing soil microbial communities to enhance ecosystem resilience in a changing global climate.

The intricate relationships between plants and soil microorganisms form a critical nexus governing ecosystem health, agricultural productivity, and global biogeochemical cycles. Within this complex web of interactions, plant vegetation and root traits serve as primary determinants shaping microbial community structure and function in soil environments. This technical whitepaper synthesizes current research on the mechanisms through which plant hosts modulate their associated microbiomes, framing these interactions within the broader context of factors influencing microbial community composition in soil research. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that plant functional traits, including root architecture, exudation profiles, and microbial interaction capabilities, selectively filter soil microorganisms, thereby driving community assembly processes [5] [21]. Understanding these plant-mediated selection mechanisms provides crucial insights for harnessing plant-microbe interactions to enhance agricultural sustainability, ecosystem resilience, and soil health.

Core Mechanisms of Plant-Mediated Microbial Modulation

Root Morphological and Architectural Traits

Root system architecture profoundly influences microbial habitat availability and heterogeneity in the rhizosphere. Plants with larger root systems and more extensive branching create greater surface area for microbial colonization and more diverse microhabitats through increased exudate gradients and niche partitioning [5]. Research on canola (Brassica napus L.) genotypes with contrasting root sizes demonstrated that a large-rooted genotype (NAM37) outperformed a small-rooted genotype (NAM23) in microbiome-intact soils, but this growth advantage disappeared in microbiome-disrupted irradiated soils [5]. This indicates that intrinsic root traits and the native soil microbiome interact dynamically to determine plant fitness, rather than root size alone conferring advantage.

Root thickness also differentially influences microbial communities, with thinner roots typically favoring bacterial colonization while thicker roots promote fungal communities, including symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi [21]. These morphological characteristics determine the physical architecture of the microbial habitat and influence resource distribution patterns.

Table 1: Root Morphological Traits and Their Effects on Microbial Communities

| Root Trait | Effect on Microbial Communities | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Total root length and branching | Creates heterogeneous microhabitats; increases microbial diversity and functional complexity | Large-rooted canola genotype (NAM37) showed growth advantage only in microbiome-intact soils [5] |

| Root thickness | Thinner roots favor bacteria; thicker roots promote fungi | Observation across potato cultivars; thinner roots with higher nitrogen availability favored bacteria [21] |

| Below-ground biomass | Positively correlates with microbiome interactive trait (MIT) scores | Field study of potato cultivars showed association between MIT scores and below-ground biomass [21] |

| Root-to-shoot ratio | Reflects resource allocation to microbial interactions | Pesticide application eliminated variation in root-to-shoot ratio among potato cultivars [21] |

Root Exudation and Chemical Signaling

Root exudates comprise a complex blend of primary and secondary metabolites that serve as chemical signals and nutrient sources for soil microorganisms. These chemical communications govern microbial attraction, colonization, and community assembly in the rhizosphere. Primary metabolites such as sugars and organic acids preferentially enrich bacterial taxa including Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, while fatty acids favor Firmicutes [21]. Secondary metabolites play more specialized roles in microbial modulation; for instance, benzoxazinoids from maize attract Chloroflexi bacteria [21], while coumarins from Arabidopsis thaliana inhibit abundant Pseudomonas species [21].

The spatial and temporal patterns of root exudation create chemical gradients that guide microbial colonization and activity. Transcriptomic analyses in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) revealed that rhizosphere restructuring activates plant-microbe interaction pathways including sugar metabolism, nitrogen metabolism, and aromatic compound degradation [22]. In contrast, native rhizosphere with higher microbial load resisted restructuring and favored metabolic pathways that preserve microbial stability, such as cell wall and signal molecule biosynthesis [22].

Plant Genotype and Microbiome Interactive Traits

Plant genotypes exhibit considerable variation in their capacity to interact with and shape microbial communities, a concept formalized as Microbiome Interactive Traits (MIT) [21]. These traits include root length, root biomass, root exudates, and the associated rhizosphere microbial community, which collectively shape dynamic plant-microbiome interactions and impact plant development [21]. Potato cultivars with higher MIT scores generally exhibited higher below-ground biomass in field conditions regardless of management treatment [21].

Plant breeding history influences MIT capabilities, as selective breeding has often diminished genetic diversity and weakened plants' ability to influence their microbiome, disrupting beneficial interactions [21]. Modern cultivar development programs are increasingly considering microbiome interaction capabilities alongside traditional agronomic traits to enhance plant resilience and reduce dependence on chemical inputs.

Environmental and Management Factors Modifying Plant-Microbe Interactions

Agricultural Management Practices

Agricultural management practices significantly alter plant-microbe relationships by modifying both the soil environment and plant physiology. Conventional management relying on chemical inputs can disrupt microbial interactions, while biological approaches enhance inter-kingdom microbial connections [21]. Research on potato cultivars demonstrated that agricultural treatments had a stronger influence on rhizosphere microbiome composition than cultivar differences, with fungal communities responding more strongly to treatments than bacterial communities [21].

Fertilizer and pesticide applications particularly impact microbial communities, with fertilizer and fertilizer-pesticide combinations causing the greatest dissimilarity from control bacterial communities, while pesticide and fertilizer-pesticide treatments most affected fungal communities [21]. These management-induced shifts in microbial composition can feedback to influence plant health and productivity.

Table 2: Agricultural Management Effects on Plant-Microbe Interactions

| Management Practice | Effect on Microbial Communities | Impact on Plant-Microbe Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Biological management (microbial consortia) | Enhances inter-kingdom microbial interactions | Improves plant performance; strengthens beneficial microbial networks |

| Chemical fertilizer | Shifts bacterial community composition | Reduces microbial diversity; disrupts functional relationships |

| Pesticides | Strongly affects fungal communities | Eliminates variation in root-to-shoot ratio among cultivars |

| Combined fertilizer-pesticide | Causes greatest dissimilarity from control communities | Disrupts both bacterial and fungal components of microbiome |

Soil Disturbance and Dysbiosis

Soil disturbances that induce microbial dysbiosis significantly alter plant-microbe interactions. Gamma irradiation of soil, which effectively reduces microbial load while preserving soil physicochemical properties, dramatically inhibits plant early growth, reducing shoot fresh mass by 8-10 fold and root fresh mass and length by 3-13 fold [5]. This growth suppression correlates with depletion of potentially beneficial taxa (e.g., Sphingomonas, certain Fusarium and Gibberella species) and enrichment of detrimental taxa (e.g., Mucilaginibacter, Leifsonia, and Trichoderma atrobrunneum) [5].

Moist heat treatment that reduced resident soil bacterial abundance by 96.4% resulted in 78% recovery after planting, which promoted plant growth and health by restructuring the rhizosphere microbiome and activating plant-microbe interaction pathways [22]. This demonstrates the resilience of soil microbial communities and their capacity for recovery following disturbance, with plants playing a crucial role in facilitating this recovery.

Abiotic Stress Factors

Drought intensity represents a significant abiotic factor that shapes soil microbial community structure and functioning, with effects that persist after re-wetting [20]. Increasing drought intensity markedly shifts bacterial and fungal community composition, with severe droughts causing changes that persist long-term, while mild drought effects are more transient [20].

Plant community composition and functional traits mediate microbial responses to drought stress. Leaf dry matter content and leaf nitrogen concentration explain significant variation in bacterial and fungal community composition during and after drought [20]. Similarly, plant community functional group abundance (grass:forb ratio) influences microbial responses to drought stress [20], highlighting how vegetation characteristics buffer microbial communities against environmental stressors.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Microbial Load Modulation Experiments

Moist heat treatment (MHT) protocols provide a controlled approach to investigating how microbial load reduction affects plant-microbe interactions. The following methodology was used to assess microbial load modulation in cucumber systems [22]:

- Soil Treatment: Apply moist heat treatment to soil to reduce resident bacterial abundance (achieving 96.4% ± 0.9% reduction)

- Planting and Monitoring: Plant Cucumis sativus L. in treated and untreated soils

- Microbial Analysis: Perform relative and quantitative rhizosphere microbiome profiling at multiple time points

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Assess plant gene expression responses to microbial inoculation in different soil conditions

- Phenotypic Assessment: Evaluate plant growth parameters and health indicators

This approach demonstrated that MHT-induced dysbiosis promoted plant growth by restructuring the rhizosphere microbiome and activating plant-microbe interaction pathways, while native rhizosphere with higher microbial load resisted restructuring [22].

Genotype Comparison Studies

Evaluating plant genotypes with contrasting root traits under different soil microbiome conditions provides insights into plant-microbiome interactions:

- Genotype Selection: Identify genotypes with contrasting root traits (e.g., large-rooted vs small-rooted canola genotypes) [5]

- Soil Treatments: Apply gamma irradiation (50 kGy minimum dose) to create microbiome-disrupted soils while preserving soil physicochemical properties [5]

- Experimental Design: Establish rhizoboxes with controlled bulk density (1.16 g cmâ»Â³) and irrigation protocols [5]

- Sampling: Collect unplanted soil, rhizosphere soil, and root samples at designated time points (e.g., 14 days post-transplant) [5]

- Microbial Profiling: Extract DNA and perform amplicon sequencing of bacterial and fungal communities [5]

- Growth Assessment: Quantify root length using WinRHIZO Tron software and measure shoot and root biomass [5]

This methodology revealed that the growth advantage of large-rooted genotypes depends on an intact soil microbiome, as both genotypes performed equally poorly in irradiated soils [5].

Microbial Inoculation Studies

Investigating how specific bacterial inoculants influence plant-associated microbiomes:

- Strain Isolation and Selection: Isolate endophytic bacteria from host plants (e.g., Artemisia species) and characterize for plant growth-promoting traits (phosphate solubilization, nitrogen fixation, pathogen antagonism) [23]

- Seed Inoculation: Surface-sterilize seeds, immerse in bacterial suspensions (OD600=1.0, ~10⸠CFU mLâ»Â¹) for 3 hours with gentle shaking [23]

- Experimental Setup: Sow treated seeds in sterilized pots with autoclaved soil under controlled greenhouse conditions [23]

- Harvest and DNA Extraction: Harvest plants at early vegetative stage (20 days, BBCH stages 11-19), surface-sterilize tissues, extract DNA [23]

- Microbial Community Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing (e.g., PacBio technology for 16S rRNA), analyze alpha and beta diversity, and conduct taxonomic annotation [23]

This approach demonstrated that inoculation with Bacillus strains AR11 and AR32 significantly influenced microbial diversity and community composition in pea plants, with AR11-treated samples enriched with beneficial taxa such as Paenibacillus, Flavobacterium, and Methylotenera [23].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Plant-microbe interactions involve sophisticated signaling pathways that regulate microbial colonization and function. Transcriptomic analyses in cucumber revealed that in dysbiotic soil conditions, bioinoculants trigger induced systemic resistance characterized by downregulation of PAL and POX gene families together with SAMDC, and upregulation of auxin-regulatory and calcium uniporter genes [22]. This response reflects a reallocation of metabolic energy from defense to growth, while maintaining active signaling for beneficial colonization and pathogen perception via modulation of calcium influx [22].

The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in plant-microbe interactions:

Figure 1: Signaling Pathways in Plant-Microbe Interactions

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plant-Microbe Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit; extracts high-quality DNA from soil samples | Microbial community analysis from rhizosphere soil [5] |

| Sterilization Agents | 70% ethanol, 2.5-5% sodium hypochlorite; surface sterilization of seeds and plant tissues | Ensuring endophytic origin of isolates; preventing contamination [23] |

| Growth Media | Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA); isolation and cultivation of bacterial isolates | Isolation of endophytic bacteria from Artemisia species [23] |

| Sequencing Technology | PacBio Sequel II; long-read sequencing for improved strain resolution | 16S rRNA amplification with primers 27F and 1492R [23] |

| Reference Databases | SILVA database (Release 138); taxonomic annotation of sequences | OTU clustering and taxonomic assignment [23] |

| Soil Sterilization Method | Gamma irradiation (50 kGy); effective microbial depletion while preserving soil properties | Creating microbiome-disrupted soils for canola experiments [5] |

| Root Imaging Software | WinRHIZO Tron software; quantification of root architecture parameters | Root length measurement in rhizobox experiments [5] |

| Statistical Analysis | R packages (vegan v2.6-4, phyloseq v1.42.0); community analysis | Beta diversity analysis using Bray-Curtis distances [23] |

Vegetation and root traits represent powerful determinants of soil microbial community structure, functioning through morphological, chemical, and genetic mechanisms that create selective environments for microorganisms. Root architectural traits define the physical habitat template, root exudates provide chemical signaling and resources, and plant genotype determines the specific interaction capacities formalized as Microbiome Interactive Traits. These plant-mediated effects are subsequently modified by environmental factors, agricultural management practices, and soil conditions, creating complex feedback loops that ultimately influence plant health, ecosystem functioning, and agricultural productivity. Understanding these multidimensional interactions provides the foundation for developing novel strategies to harness plant-microbe relationships for sustainable agriculture, including the design of crop cultivars with enhanced microbiome interaction capabilities and management practices that support beneficial plant-microbe partnerships. Future research priorities include overcoming technical challenges in microbiome measurement, improving integration of multi-omics data, and translating basic research findings into field-ready applications that are robust across diverse environmental contexts [24].

Nutrient availability is a primary determinant of soil microbial community composition and function, creating a critical linkage between aboveground plant communities and belowground biological processes. Within terrestrial ecosystems, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and essential micronutrients operate in a complex balance that regulates microbial diversity, enzymatic activity, and biogeochemical cycling. Understanding the relative roles of these nutrients is fundamental to predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change and developing sustainable land management practices. This technical review synthesizes current research on how nutrient limitations shape soil microbial communities, with particular emphasis on the mechanistic pathways through which N, P, and micronutrients independently and interactively influence belowground ecological processes. The content is framed within the context of a broader thesis on factors influencing microbial community composition in soil research, providing researchers and scientists with experimental frameworks and analytical approaches for investigating nutrient-microbe interactions.

Nitrogen Limitations and Microbial Community Dynamics

Nitrogen Addition Effects on Microbial Diversity and Function

Nitrogen availability significantly constrains soil microbial communities, with profound implications for ecosystem functioning. Experimental evidence from subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests demonstrates that N addition induces dose-dependent reductions in both bacterial and fungal diversity [25]. This diversity loss correlates strongly with suppressed activity of key ecological enzymes including invertase (Inv), urease (Ure), and acid phosphatase (ACP), while catalase (CAT) activity shows enhancement under N enrichment [25]. These enzymatic shifts reflect fundamental alterations in microbial metabolic priorities and carbon acquisition strategies under changing N availability.

The mechanisms underlying these changes involve both direct and indirect pathways. Nitrogen addition directly alters soil physicochemical properties, reducing pH and increasing osmotic stress, which selectively inhibits sensitive microbial taxa [25]. Indirectly, N-mediated changes in plant community composition and root exudation patterns further modify the microbial habitat. Co-linearity network analyses reveal that bacterial communities typically show stronger interactions with ecological enzymes, while fungal associations are more closely linked with nutrient pools, suggesting functional complementarity between these microbial domains [25].

Table 1: Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Soil Microbial Properties and Nutrient Dynamics

| Parameter | Low N (10 g/m²/yr) | Medium N (20 g/m²/yr) | High N (25 g/m²/yr) | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Diversity | Moderate decrease | Significant decrease | Severe decrease | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shannon index |

| Fungal Diversity | Moderate decrease | Significant decrease | Severe decrease | ITS sequencing, Shannon index |

| Invertase Activity | 15-20% inhibition | 30-40% inhibition | 50-60% inhibition | Colorimetric enzyme assays |

| Urease Activity | 10-15% inhibition | 25-35% inhibition | 45-55% inhibition | Colorimetric enzyme assays |

| Acid Phosphatase Activity | 5-10% inhibition | 20-25% inhibition | 35-45% inhibition | Colorimetric enzyme assays |

| Soil Organic Carbon | 5-8% decrease | 12-15% decrease | 18-22% decrease | Elemental analysis |

| Total Nitrogen | 3-5% decrease | 8-10% decrease | 12-15% decrease | Elemental analysis |

Plant Diversity as a Buffer to Nitrogen-Induced Changes

Emerging evidence suggests that plant diversity can modulate microbial responses to N deposition. In grassland ecosystems, high plant diversity alleviates the negative effects of N addition on soil nitrogen cycling multifunctionality (NCMF) [26]. This buffering capacity operates through multiple mechanisms: diverse plant communities increase soil organic matter via varied root architectures and carbon inputs, thereby reducing microbial carbon limitation and supporting more robust nutrient cycling [26]. The carbon inputs from diverse plant root systems provide essential energy sources for carbon-intensive microbial processes, maintaining metabolic activity despite N-induced stress.

The interaction between plant diversity and N deposition creates a complex feedback system where plant community composition influences microbial function, which in turn regulates nutrient availability for plants. This relationship highlights the importance of considering aboveground-belowground linkages when predicting ecosystem responses to anthropogenic N deposition and developing management strategies to mitigate its impacts.

Phosphorus Limitations and Microbial Adaptation Strategies

Microbial Responses to Phosphorus Scarcity

Phosphorus limitation triggers sophisticated microbial adaptation strategies that enhance P acquisition and conservation. Research in forest ecosystems reveals that microbes respond to P scarcity through multiple complementary mechanisms: increased production of phosphatase enzymes, enhanced expression of P transporter genes, and shifts in community composition toward taxa with specialized P acquisition capabilities [27]. The relative importance of these strategies varies across ecosystem types, with subtropical forests generally exhibiting stronger P limitation than temperate forests.

In subtropical forests, P limitation induces a coordinated response involving "transporter genes + trophic structure + enzyme catalytic efficiency" that enhances microbial P acquisition capacity [27]. Nitrogen addition in P-limited systems further intensifies P limitation by increasing microbial demand, leading to upregulated expression of P transporter genes (e.g., pstB) and enhanced microbial capacity for inorganic P uptake [27]. This response demonstrates the interactive effects of multiple nutrient limitations on microbial physiological adaptation.

Table 2: Microbial Phosphorus Acquisition Strategies Under Phosphorus Limitation

| Adaptation Strategy | Mechanism | Key Microbes Involved | Environmental Triggers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatase Enzyme Production | Organic P mineralization through enzymatic hydrolysis | Bacteria with phoD genes; AM fungi | Low available P; High organic P |

| P Transporter Upregulation | Enhanced inorganic P uptake | Acidobacteria; Pseudomonadota | N addition; Low inorganic P |

| Trophic Reorganization | Predation pressure on bacteria releasing P | Protists | N and P co-addition |

| Community Composition Shift | Enrichment of P-efficient taxa | Rare taxa like nitrogen-fixing bacteria | Persistent P limitation |

| Mycorrhizal Associations | Hyphal extension increasing P exploration area | AM and ECM fungi | Low P mobility in soil |

Enzymatic Adaptations to Phosphorus Limitation

Phosphorus cycling in forest ecosystems is strongly regulated by microbial enzymatic processes. The kinetic parameters of phosphatase enzymes, including their catalytic efficiency, show contrasting responses to N and P additions [27]. While N addition generally increases phosphatase activity and catalytic efficiency in P-limited systems, P addition typically suppresses these parameters in forests with strong pre-existing P limitation [27]. These responses represent a sophisticated microbial regulatory strategy that optimizes metabolic investment in P acquisition based on environmental availability.

The relationship between nutrient availability and enzymatic investment follows economic principles of resource allocation, where microbes balance the metabolic cost of enzyme production against the nutrient gain from substrate hydrolysis. This balance is reflected in the stoichiometry of ecological enzymes, with studies across the North-South Transect in Eastern China showing that soil microbial communities in P-limited systems adjust enzyme ratios to alleviate P constraints [27].

Micronutrient Limitations and Microbial Community Structure

Differential Effects of Micronutrient Deficiencies

Micronutrients, though required in trace amounts, exert disproportionate influence on soil microbial communities and plant-microbe interactions. Controlled studies using axenic systems demonstrate that deficiencies in copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), molybdenum (Mo), and boron (B) differentially reshape microbial community structure and function [28]. Cu deficiency reduces bacterial alpha diversity (25% decline in Shannon index), while Mn, Mo, and B deficiencies enhance microbial richness (Chao1 increase: 15-30%) [28]. These contrasting effects highlight the element-specific roles micronutrients play in microbial physiology.

Taxonomic profiling reveals that specific microbial genera show distinct responses to micronutrient limitations. Stress-adapted genera including Luteibacter, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia emerge as key responders, while Pseudomonas abundance decreases under Cu and B deficiency but increases under Mn and Mo deprivation [28]. These taxonomic shifts have functional consequences, with Cu deficiency suppressing photosynthesis-associated bacteria and Mo limitation enriching nitrogen-cycling taxa such as denitrifiers [28].

Network Interactions Under Micronutrient Stress

Co-occurrence network analysis provides insights into how micronutrient limitations alter microbial interaction patterns. Mn and Mo deficiencies intensify microbial interactions, resulting in more complex and interconnected networks, while Cu and B deficiencies reduce network connectivity and stability [28]. These patterns suggest that certain micronutrient limitations may foster microbial cooperation and functional redundancy, while others disrupt community organization.

The network approach reveals a bidirectional "plant-microbe" regulatory axis where micronutrient availability mediates communication between plants and their associated microbiota. Cu deficiency directly impairs plant growth by disrupting photosynthetic symbionts and enriching potential pathogens, while Mn and Mo deprivation enrich endophytic taxa linked to nutrient metabolism and stress resilience [28]. This axis represents an important mechanism through which micronutrients influence plant health and ecosystem productivity.

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Nutrient Limitations

Experimental Designs for Manipulating Nutrient Availability

Research on nutrient limitations employs diverse experimental designs to isolate specific nutrient effects. Fully factorial microcosm experiments manipulating both plant diversity and nitrogen addition allow researchers to examine interactive effects on soil nitrogen cycling multifunctionality (NCMF) [26]. Similarly, nutrient omission designs (e.g., NPK, PK, NK, NP treatments) enable identification of specific nutrient limitations in agricultural systems [29]. These approaches reveal that balanced NPK fertilization increases microbial diversity and abundance compared to nutrient-deficient treatments [29].

Long-term nutrient addition experiments in forest ecosystems provide insights into cumulative nutrient effects. The use of reference plots (CK, 0 g N mâ»Â² yearâ»Â¹) alongside low (LN: 10 g N mâ»Â² yearâ»Â¹), medium (MN: 20 g N mâ»Â² yearâ»Â¹), and high nitrogen (HN: 25 g N mâ»Â² yearâ»Â¹) treatments establishes dose-response relationships that clarify N threshold effects [25]. Such experiments demonstrate that surface soils typically show the highest microbial diversity, ecological enzyme activities, and nutrient contents, highlighting the importance of stratification in soil sampling designs.

Microbial Community Manipulation Techniques

Soil autoclaving provides a rapid method for creating sterile conditions to investigate microbial functions in nutrient cycling. When combined with serial dilution and reinoculation approaches (e.g., AS, AS+10â»Â¹, AS+10â»Â³, AS+10â»â¶, NS), this method allows researchers to establish gradients of microbial diversity and examine their consequences for N and P dynamics [30]. Following reinoculation, microbial activity (measured via 14COâ‚‚ respiration) can exceed that of non-sterile controls, demonstrating functional redundancy in soil communities [30].

Isotopic tracing techniques using ¹â´C-glucose and ³³P provide sensitive measures of microbial metabolic activity and nutrient transformation processes. These approaches reveal that autoclaving procedures alter nutrient availability, reducing ³³P lability and increasing N-NH₄⺠concentration regardless of microbial community structure [30]. Such findings highlight the importance of accounting for methodology-induced artifacts when interpreting nutrient dynamics data.

Nutrient Effects on Soil Microbes

Analytical Techniques for Assessing Microbial Community Structure

High-throughput sequencing of marker genes (16S rRNA for bacteria, ITS for fungi) provides comprehensive characterization of microbial community composition in response to nutrient manipulations [28] [31]. When combined with co-occurrence network analysis, this approach reveals how nutrient limitations alter microbial interaction patterns, with continuous cropping systems showing reduced fungal network complexity and weakened bacterial-fungal interactions [31]. These network disruptions correlate with increased pathogen abundance and ecosystem dysfunction.

Integration of molecular data with soil chemical analyses through redundancy analysis (RDA) identifies key environmental drivers of microbial community structure. Studies consistently identify pH, total nitrogen (TN), nitrate nitrogen (NO₃â»-N), ammonium nitrogen (NHâ‚„âº-N), and total organic carbon (TOC) as critical factors shaping microbial communities under nutrient stress [31]. This multivariate approach helps disentangle the complex interplay between nutrient availability and microbial ecology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Nutrient-Microbe Interactions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer Formulations | Urea [CO(NHâ‚‚)â‚‚], Superphosphate, Potassium sulfate | Nutrient addition experiments | Purity, solubility, application rate calibration |

| Isotopic Tracers | ¹â´C-glucose, ³³P-labeled compounds | Tracking nutrient pathways and transformations | Half-life, detection method, safety protocols |

| DNA Extraction Kits | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (QIAGEN) | Microbial community analysis | Yield, inhibitor removal, compatibility with downstream applications |

| PCR Reagents | 16S rRNA primers (515F/806R), ITS primers (ITS5-1737F) | Amplicon sequencing | Specificity, amplification efficiency, bias minimization |

| Enzyme Assay Reagents | p-Nitrophenol substrates, MUB-based substrates | Extracellular enzyme activity measurement | Substrate saturation, pH optimum, incubation time |

| Sterilization Agents | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Axenic system creation | Concentration optimization, plant toxicity assessment |

| Growth Media Components | Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium, Plant growth regulators | Controlled plant-microbe studies | Nutrient composition, pH adjustment, sterilization method |

| a15:0-i15:0 PE | a15:0-i15:0 PE, MF:C35H70NO8P, MW:663.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (S)-ZLc002 | (S)-ZLc002, MF:C10H17NO5, MW:231.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Nitrogen, phosphorus, and micronutrients each play distinct but interconnected roles in regulating soil microbial community composition and function. Nitrogen limitations typically dominate temperate ecosystems, triggering microbial enzymatic responses that enhance N availability but often at the cost of reduced diversity under elevated N inputs. Phosphorus limitations prevail in many tropical and subtropical systems, driving sophisticated microbial adaptations involving phosphatase production, transporter gene expression, and trophic reorganization. Micronutrient limitations introduce additional complexity, with element-specific effects on microbial network structure and plant-microbe interactions. Understanding these hierarchical nutrient limitations provides a conceptual framework for predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change and developing targeted management strategies that optimize nutrient availability for sustainable ecosystem functioning. Future research should prioritize multi-nutrient factorial experiments that capture interactive effects and leverage emerging molecular techniques to resolve mechanistic links between nutrient availability, microbial physiology, and ecosystem processes.

Research Framework Guide

Understanding the factors that influence soil microbial community composition requires a explicit multiscale perspective. A central thesis emerging in microbial ecology is that the drivers of community structure and function are not static; they shift profoundly across spatial and temporal scales [32] [33]. At the scale of individual soil aggregates, biological interactions and micron-scale resource heterogeneity dominate. In contrast, at regional and global scales, climatic factors and major soil edaphic properties become the primary determinants of microbial biogeography [34]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on these scaling relationships, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists on the concepts, methodologies, and quantitative patterns that define how microbial drivers change from aggregate to regional levels. This framework is critical for accurately interpreting experimental data, designing ecological studies, and predicting how microbial communities and their associated ecosystem functions will respond to global change.

Spatial Scaling: From Centimeter Heterogeneity to Continental Patterns

Quantitative Patterns of Spatial Scaling

The spatial scaling of soil microbial communities is characterized by a transition from extreme patchiness at fine scales to coherent biogeographical patterns at broader scales. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on how drivers change across spatial extents.

Table 1: Scaling of Microbial Community Properties and Their Drivers Across Spatial Extents

| Spatial Scale | Key Community Properties | Dominant Drivers | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centimeter Scale (Aggregate to Core) | Pronounced heterogeneity; Relative abundance of dominant phyla (e.g., Verrucomicrobia) can vary 2.5-fold within a 10x10 cm grid [32]. | Micro-environmental heterogeneity; Micron-scale resource patches; Biological interactions. | Lack of significant spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I ~ -0.024); No significant correlation between pairwise UniFrac distances and spatial distance [32]. |

| Ecosystem Scale (Meters to Kilometers) | Significant but subtle shifts in community composition and structure; Higher alpha diversity observed in fertilized plots [32]. | Land management (e.g., fertilization); Plant cover; Soil type; pH. | Coherent patterns emerge despite fine-scale patchiness; 20% of bacterial taxa shared with globally sourced samples [32]. |

| Regional Scale (Continental) | Microbial biomass carbon stocks show strong spatial patterns; Decreased by 3.4% globally from 1992-2013, with strongest decreases in northern high-latitude regions [34]. | Primary: Mean Annual Temperature, Soil Organic Carbon, Soil pH [34]. Secondary: Precipitation, Land-Cover Type, Clay Content [33] [34]. | Machine learning models (Random Forest) identify temperature as the most important predictor; Non-linear relationships with clay content and pH [34]. |

Vertical Scaling with Soil Depth

The determinants of microbial communities are not consistent throughout the soil profile, adding a critical vertical dimension to spatial scaling.

Table 2: Scaling of Microbial Drivers and Function with Soil Depth

| Soil Layer | Microbial Biomass & Diversity | Dominant Drivers | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topsoil (e.g., 0-20 cm) | Higher biomass and diversity [35]; Strongest response to global change drivers [34]. | Plant-related factors (biomass, exudates); Organic carbon inputs; Aridity [33]. | Fast bacterial-based energy channel; Strong links to plant productivity. |

| Subsoil (e.g., 20-100 cm) | Lower biomass but significant (35-60% of total profile) [33]; Increased relative abundance of archaea with depth [35]. | Abiotic environmental factors (e.g., soil pH, bulk density) [33]; Adaptation to lower-nutrient conditions [35]. | Slow fungal-based energy channel; Key role in nutrient mineralization and groundwater quality. |

Figure 1: Conceptual diagram of how primary drivers of soil microbial communities shift across spatial scales and soil depth.

Temporal Scaling: From Diel Cycles to Decadal Trends