Microbial Community Composition and Structure Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of microbial community analysis, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Microbial Community Composition and Structure Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of microbial community analysis, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. We cover foundational ecological principles governing community assembly and delve into cutting-edge molecular techniques, including high-throughput 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics. The article provides rigorous methodological comparisons and introduces advanced computational approaches like graph neural networks and LSTM models for predicting community dynamics. Special emphasis is placed on troubleshooting common experimental pitfalls in low-biomass studies like cancer microbiome research and optimizing bioinformatics pipelines. By synthesizing validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics across tools and environments—from human gut to wastewater ecosystems—this resource offers both theoretical understanding and practical guidance for robust experimental design and data interpretation in biomedical applications.

Understanding Microbial Ecosystems: Core Principles and Ecological Significance

Microbial community structure represents a foundational concept in microbial ecology, describing the organization and interplay of microorganisms within a shared environment. This structure is defined by three core pillars: composition (the identity of the taxa present), diversity (the variety and abundance distribution of these taxa), and dynamics (the temporal changes in community properties) [1]. Understanding these elements is critical for researchers and drug development professionals as it provides insights into community function, stability, and its impact on host health and disease states. The complex nature of microbiome data—characterized by high dimensionality, compositionality, and zero-inflation—requires sophisticated statistical models and experimental methods to accurately describe and predict community behavior [2]. This guide synthesizes current methodologies and analytical frameworks for defining microbial community structure within the broader context of microbial ecology and therapeutic development.

Core Components of Microbial Community Structure

Composition: The "Who is There"

Community composition refers to the identity of the microorganisms present in a sample, typically characterized using taxonomic labels from domain to species level. Advances in culture-independent metagenomic sequencing have revealed that the human microbiome comprises thousands of taxa from Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya, with the gut hosting the highest microbial load and functional potency [1]. A key challenge is that a significant portion of microbial sequences remains unassigned, corresponding to "microbial dark matter," which necessitates complementary culture-dependent approaches for comprehensive characterization [3].

Diversity: The Variety of Life

Microbial diversity quantifies the variety of microorganisms within a community, encompassing multiple levels of biological organization from genetic to ecological diversity [4]. This concept is operationalized through several key metrics:

- Alpha Diversity describes the diversity within a single community, incorporating species richness (the number of different species) and species evenness (how evenly individuals are distributed across those species) [5].

- Beta Diversity measures the similarity or dissimilarity in taxonomic diversity between different microbial communities [5].

- Gamma Diversity represents the overall diversity for all different ecosystems within a larger region [5].

Table 1: Common Alpha Diversity Metrics

| Metric | Description | Formula/Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Margalef's Richness | Estimates species richness, accounting for community size. | ( D = \frac{(S - 1)}{\log(n)} ) where (S) is total species and (n) is total individuals [5]. |

| Chao1 | Estimates true species richness, incorporating unobserved rare species. | ( S{chao1} = S{obs} + \frac{n{1}(n{1} - 1)}{2(n2 + 1)} ) where (n1) is singletons and (n_2) is doubletons [5]. |

| ACE (Abundance-based Coverage Estimator) | Estimates species richness based on abundance distribution, incorporating rare species. | Not covered in detail by search results. |

Dynamics: Temporal Changes and Interactions

Dynamics refer to the temporal changes in community composition, diversity, and function. Individual species abundances can fluctuate greatly over time with limited recurring patterns, making accurate forecasting a major challenge [6]. These dynamics are shaped by a complex interplay of deterministic factors (e.g., temperature, nutrients, predation), stochastic factors (e.g., immigration), species-species interactions, and evolutionary processes [6] [7]. Emerging graph neural network models can now predict species-level abundance dynamics up to 2-4 months into the future using historical relative abundance data [6].

Methodologies for Analysis

A comprehensive analysis of microbial community structure requires an integrated approach, combining both classical and modern molecular techniques.

Traditional Culture-Dependent Methods

Traditional methods rely on microbial isolation and pure culture, using microscopic observation and physiological characterization to understand community structure. While foundational, these methods have critical limitations, as a large proportion of environmental microorganisms are unculturable, making it impossible to capture the full community diversity [4].

- Experimental Protocol: Experienced Colony Picking (ECP)

- Sample Preparation: Fresh fecal sample (0.5 g) is homogenized with 4.5 g of distilled water, and tenfold serial dilutions are prepared in 0.85% NaCl solution [3].

- Plating: Aliquots (200 µL) from dilutions (e.g., 10â»Â³ to 10â»â·) are plated on various agar media types (e.g., nutrient-rich, selective, oligotrophic) [3].

- Incubation: Plates are incubated anaerobically (95% N₂, 5% H₂) and aerobically at 37°C for 5-7 days [3].

- Colony Selection & Purity: One or two single colonies of the same type are selected based on size, shape, color, and protrusion. Selected colonies are streaked on solid medium for purification to obtain pure culture isolates [3].

- Identification: DNA of isolated strains is extracted, and the 16S rRNA gene is amplified via PCR and sequenced for taxonomic identification [3].

Modern Culture-Independent Molecular Methods

These methods bypass the need for cultivation, providing a more comprehensive view of microbial communities.

Metagenomic Sequencing: This involves the functional and sequence-based analysis of the collective microbial genomes contained in an environmental sample. It provides a comprehensive view of genetic diversity, species composition, and functional potential [4].

- Experimental Protocol: Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing (CIMS)

- DNA Extraction: Metagenomic DNA is extracted directly from a sample (e.g., ~100 mg of stool) using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) [3].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: DNA libraries are constructed from fragments (~300 bp) and sequenced using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq 2500) to generate paired-end reads (e.g., 100 bp forward and reverse) [3].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Low-quality reads, adapters, and host contaminants are removed. Taxonomic profiling is performed using tools like MetaPhlAn2, and functional analysis is conducted by aligning reads to databases like UniRef and KEGG [3].

- Experimental Protocol: Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing (CIMS)

Hybrid Approaches: Newer methodologies aim to bridge the gap between culture-dependent and independent methods.

- Experimental Protocol: Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS)

- Culturing: Samples are cultured extensively under multiple conditions (e.g., 12 different media, anaerobic/aerobic) [3].

- Harvesting: Instead of picking single colonies, all colonies from the culture plates are collected by scraping the plate surfaces and pooling the biomass [3].

- DNA Sequencing & Analysis: Metagenomic DNA is extracted from this pooled biomass and subjected to shotgun metagenomic sequencing, followed by the same bioinformatic analysis as in CIMS [3]. This method identifies a broader spectrum of culturable microorganisms than conventional ECP [3].

- Experimental Protocol: Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS)

Other Molecular Techniques: Several other techniques are used for microbial community fingerprinting, including Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE), Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (T-RFLP), and Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH) [4].

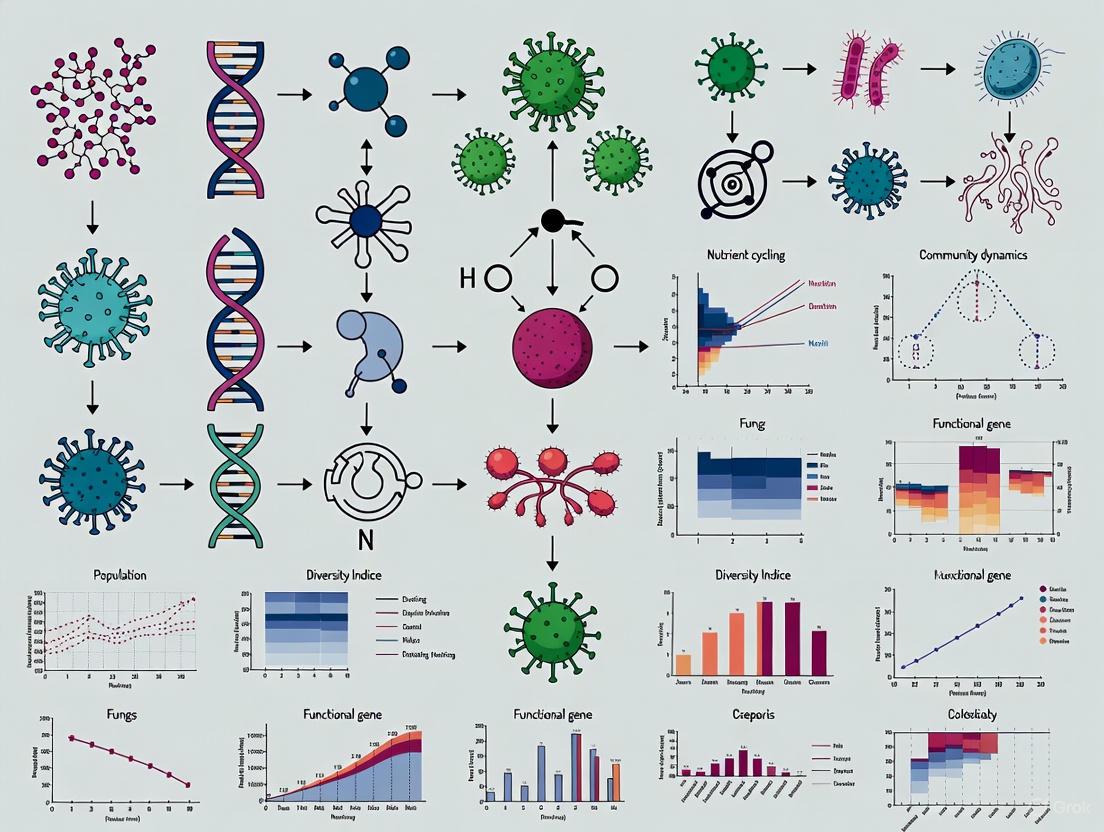

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in selecting an appropriate method for profiling microbial community structure.

Statistical Modeling and Data Visualization

Statistical models are essential for describing and simulating realistic microbial community profiles, accounting for their unique properties like compositionality, sparsity, and high dimensionality.

SparseDOSSA Model: SparseDOSSA (Sparse Data Observations for the Simulation of Synthetic Abundances) is a hierarchical model that captures the main characteristics of microbiome data [2].

- Components: It uses zero-inflated log-normal distributions for marginal microbial abundances, a multivariate Gaussian copula to model feature-feature correlations, and a multinomial model for the read count generation process, while also accounting for compositionality [2].

- Application: This model can be fit to real data to parameterize community structures and then "reversed" to simulate synthetic, realistic microbial profiles with known ground truth. This is invaluable for benchmarking analytical methods, conducting power analyses, and spiking-in known microbial-phenotype associations [2].

Data Visualization Rules: Effective colorization of biological data visualizations is critical for clear communication. Key rules include [8]:

- Rule 1: Identify the nature of your data (e.g., Nominal: species names; Ordinal: disease severity; Quantitative: age, abundance).

- Rule 2: Select an appropriate color space (e.g., perceptually uniform CIE Luv/Lab is superior to standard RGB).

- Rule 7: Be aware of color conventions in your discipline.

- Rule 8: Assess color deficiencies to ensure accessibility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microbial Community Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | To support the growth of specific microbial groups from complex communities. | LGAM, PYG (nutrient-rich); PYA, PYD (probiotic enrichment); selective media like MRS-L for Bifidobacterium, RG for Lactobacillus [3]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | To isolate high-quality metagenomic DNA directly from samples or cultured biomass. | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [3]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | To amplify a phylogenetic marker gene for identification of bacterial isolates or community profiling via amplicon sequencing. | Universal primers for PCR amplification followed by Sanger sequencing of isolates [3]. |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits | To prepare DNA libraries for high-throughput sequencing on platforms like Illumina. | Illumina library preparation kits for 300 bp fragments and 100 bp paired-end sequencing on HiSeq 2500 [3]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools & Databases | For taxonomic profiling, functional annotation, and diversity analysis of sequencing data. | Kraken2/Bracken (taxonomic profiling), HUMAnN2/MetaPhlAn2 (community profiling & function), MiDAS database (ecosystem-specific taxonomy) [6] [5] [3]. |

| Statistical Software & Models | For modeling community structure, simulating data, and performing differential analysis. | SparseDOSSA2 (R/Bioconductor package for modeling/simulation) [2]. |

| Kadsuracoccinic Acid A | Kadsuracoccinic Acid A, MF:C30H44O4, MW:468.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Thienamycin | (+)-Thienamycin, CAS:65750-57-4, MF:C11H16N2O4S, MW:272.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Interplay Between Structure, Function, and Dynamics

A central question in microbial ecology is the relationship between community structure ("who is there") and ecosystem function ("what they are doing"). The strength of this relationship is mediated by several factors [7]:

- Trait-Based Approaches: The distribution of functional traits within a community (e.g., plasticity, redundancy, enzyme production) provides a mechanistic link between structure and function. Communities with greater functional redundancy may be more resilient to perturbations [7].

- Species Interactions: Interactions such as cooperation, competition, and cheating (organisms using a public good without contributing) can significantly alter the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem function [7].

- Evolutionary Dynamics: Horizontal gene transfer and within-lineage diversification can decouple phylogenetic structure from functional output, emphasizing the need for fine-scale resolution in analyses [7].

- Community Assembly: The processes governing how communities form (deterministic vs. stochastic) can influence the subsequent link between the resulting structure and its function [7].

- Physical Dynamics: Community structure is most likely to influence ecosystem function when biological processes are rate-limiting, rather than when physical constraints (e.g., diffusion limitations) dominate [7].

The following diagram illustrates the complex, interconnected factors that govern the relationship between microbial community structure and its resulting function, as identified in contemporary research.

Advanced Predictive Modeling of Community Dynamics

Accurately forecasting the future dynamics of individual microbial species remains a major challenge. A recently developed graph neural network (GNN) model demonstrates the ability to predict species-level abundance dynamics up to 2-4 months into the future using only historical relative abundance data [6].

- Model Architecture and Workflow:

- Input: Moving windows of 10 consecutive historical time points from a multivariate cluster of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [6].

- Processing Layers:

- Graph Convolution Layer: Learns and extracts interaction features and relational dependencies between ASVs [6].

- Temporal Convolution Layer: Extracts temporal features across the time series data [6].

- Output Layer: Uses fully connected neural networks to predict the relative abundances of each ASV for the next 10 time points [6].

- Pre-clustering: Pre-clustering ASVs (e.g., using graph network interaction strengths or ranked abundances) before model training significantly enhances prediction accuracy compared to clustering by known biological function [6].

- Application: This approach, implemented as the "mc-prediction" workflow, was validated on 24 wastewater treatment plants and also shown to be suitable for other ecosystems like the human gut microbiome [6].

Microbial interactions function as a fundamental unit in complex ecosystems, serving as a critical determinant of community composition, structure, and function [9]. These interactions, ranging from positive to negative and neutral, are ubiquitous, diverse, and critically important in the function of any biological community, influencing processes from global biogeochemistry to human health and disease [9] [10]. Understanding the nature of these dynamic relationships allows researchers to unravel the ecological roles of microbial species, predict community behavior, and manipulate consortia for applications in biotechnology, medicine, and environmental management [9]. The characterization of these interactions—including their directionality, reciprocity, strength, and mode of action—provides invaluable insights into the stability and functional output of microbial systems [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for classifying and analyzing these relationships within the context of microbial community composition and structure analysis research, equipping scientists with the methodologies and conceptual models needed to decipher complex microbial ecosystems.

A Classification System for Microbial Interactions

Microbial interactions are fundamentally categorized based on the net effect they have on the interacting partners, classified as positive, negative, or neutral [9] [10]. In these dynamic systems, positive interactions are defined as those wherein at least one partner benefits, negative interactions are those where one microbial population negatively affects another, and neutral interactions have no measurable effect [9]. The table below provides a systematic overview of these interaction types, their effects on the involved organisms, and specific examples.

Table 1: Classification of Microbial Interaction Types

| Interaction Type | Effect on Organism A | Effect on Organism B | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism [10] | Benefit | Benefit | An obligatory relationship where both organisms are metabolically dependent on each other [10]. | Lichens (fungi + algae), syntrophic methanogenic consortia in sludge digesters [10]. |

| Protocooperation [10] | Benefit | Benefit | A non-obligatory mutualistic interaction [10]. | Desulfovibrio and Chromatium; N2-fixing and cellulolytic bacteria [10]. |

| Commensalism [10] | Benefit | Neutral | One organism benefits while the other remains unaffected [10]. | E. coli consumes oxygen, creating an anaerobic environment for Bacteroides [10]. |

| Predation [10] | Benefit | Harm | One organism (predator) engulfs or attacks another (prey), typically causing death [10]. | Protozoa feeding on soil bacteria; predatory bacteria like Bdellovibrio [10]. |

| Parasitism [10] | Benefit | Harm | One organism (parasite) derives nutrition from a host, harming it over a prolonged period [10]. | Bacteriophages; Bdellovibrio as an ectoparasite of gram-negative bacteria [10]. |

| Competition [10] | Harm | Harm | Both populations are adversely affected while competing for the same limited resources [10]. | Paramecium caudatum and P. aurelia competing for the same bacterial food source [10]. |

| Amensalism (Antagonism) [10] | Neutral (or unaffected) | Harm | One population produces substances that inhibit another population [10]. | Lactic acid bacteria inhibiting Candida albicans in the vaginal tract [10]. |

Methodologies for Characterizing Interactions

Qualitative and Observational Methods

Qualitative assessment forms the foundational step in identifying microbial interactions, focusing on phenotypic changes and spatial structures [9]. These methods provide direct observation of inter-species dynamics.

- Co-culturing Experiments: Cultivating microbial species together, either with direct cell-cell contact or separated by a membrane, allows for the observation of directional interactions, mode of action, and spatiotemporal variation [9]. This can include plating assays, two-chamber systems, and host-microbe co-cultures to mimic in vivo conditions [9].

- Microscopy and Imaging: Techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) are used to visualize mixed-species biofilm structures, morphological changes, and physical co-aggregation [9]. Time-lapse imaging in specialized chambers (e.g., MOCHA) can track colony morphology dynamics and morphogenesis in response to co-culturing [9].

- Analysis of Chemical Compounds: Microbial interactions are often mediated by secreted compounds.

- Volatile Compounds: Assessing the transcriptional or growth response of one microbe to volatiles produced by a co-inhabitant [9].

- Quorum Sensing Signals: Using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to identify and quantify autoinducers and other signaling molecules involved in microbial communication [9].

- Metabolite Exchange: Detecting cross-fed metabolites, enzymes, or nutrients that suggest syntrophy or competition [9].

Quantitative and Computational Methods

Quantitative methods leverage high-throughput data and computational models to infer interactions and predict community dynamics, offering a systems-level perspective [6] [9].

- Network Inference and Construction: Microbial association networks are constructed from abundance data (e.g., from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing) to visualize and quantify potential positive and negative correlations between species [9]. This helps generate hypotheses about interaction partners.

- Dynamic Modeling with Machine Learning: Advanced computational models, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), use historical relative abundance data to predict future community dynamics [6]. These models learn interaction strengths and temporal features to accurately forecast species-level abundances multiple time points into the future, without relying on environmental parameters [6].

- Functional Prediction from Genomic Data: Tools like PICRUSt2 are used to predict the metabolic functional potential of a microbial community based on marker-gene sequencing data [11]. This helps infer the ecological roles of symbionts and how their functional profiles (e.g., denitrification, vitamin synthesis) contribute to interactions and host health [11].

- Synthetic Microbial Consortia: Designed communities of known species are constructed to quantitatively test and validate hypothesized interactions in a controlled setting, providing a framework for understanding the principles of community assembly and function [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of these diverse methodologies to progress from observation to prediction in microbial interaction analysis.

Diagram 1: An integrated workflow for analyzing microbial interactions, combining qualitative observations with quantitative modeling.

Advanced Computational Modeling: Predicting Community Dynamics

The ability to predict the temporal dynamics of individual microbial species is a major frontier in microbial ecology. A graph neural network (GNN)-based approach demonstrates the power of computational models to forecast community structure [6].

- Model Architecture: The GNN model uses only historical relative abundance data (e.g., from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing) as input. Its architecture consists of:

- Graph Convolution Layer: Learns the interaction strengths and extracts relational features between amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [6].

- Temporal Convolution Layer: Extracts temporal features across consecutive time points [6].

- Output Layer: Uses fully connected neural networks to predict future relative abundances of each ASV [6].

- Input and Output: The model is trained on moving windows of 10 consecutive historical samples to predict the next 10 consecutive time points, enabling predictions 2-4 months into the future [6].

- Pre-clustering for Accuracy: Model performance is optimized by pre-clustering ASVs (e.g., into groups of 5) before training. Clustering based on graph network interaction strengths or by ranked abundances yields the highest prediction accuracy, outperforming clustering by biological function [6].

This modeling approach, implemented in the "mc-prediction" software workflow, is generic and has been successfully applied to ecosystems ranging from wastewater treatment plants to the human gut microbiome [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Microbial Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| PET Membranes / Two-Chamber Assays [9] | Enables co-culturing of microbes with indirect contact, allowing study of metabolite and volatile compound exchange. |

| Fluorescent Labels & Tags [9] | Used for tracking and visualizing specific microorganisms within mixed communities via microscopy (e.g., CLSM). |

| Sterile Swabs & Cell Lifters [11] | For the non-destructive collection of mucosal surface microbiota (e.g., gill, skin, intestinal mucus) from host organisms. |

| DNA Extraction Kits [6] [11] | Essential for extracting high-quality genomic DNA from complex community samples for subsequent sequencing. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers & Sequencing Kits [6] [11] | Allows for amplicon sequencing to determine microbial community composition and structure at high resolution. |

| PCTE Membrane Filters (0.2µm) [11] | For filtering water samples to collect microbial biomass for environmental association analysis. |

| LC-MS Reagents & Columns [9] | For identifying and quantifying metabolites, quorum sensing molecules, and other chemical mediators of interaction. |

| ELISA Kits (e.g., for cortisol, estradiol) [11] | To measure host stress or physiological response biomarkers correlated with shifts in microbial communities. |

| IOX5 | IOX5, MF:C17H19F3N4O2, MW:368.35 g/mol |

| Amylin (8-37), human | Amylin (8-37), human, MF:C138H216N42O45, MW:3183.4 g/mol |

Visualization and Data Interpretation Guidelines

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting complex interaction data, such as microbial networks. Adherence to design principles ensures clarity and accuracy.

- Color Contrast in Diagrams: For node-link diagrams, ensure sufficient contrast between all elements (nodes, edges, labels) and the background [12]. When nodes are colored to represent quantitative attributes (e.g., abundance), use shades of blue over yellow for better perception, and pair with complementary-colored or neutral gray links to enhance node color discriminability [13].

- Color Palette and Order: Use a controlled color palette with distinct hues and consistent perceived lightness to represent different microbial groups or interaction types [14]. If coloring edges based on a node attribute, carefully consider the rationale—using source node color, target node color, or a mix of both—and randomize edge drawing order to prevent visual bias [14].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized model of positive and negative interaction mechanisms at the metabolic level.

Diagram 2: Mechanisms of positive (syntrophy) and negative (amensalism) microbial interactions.

Understanding the ecological drivers of microbial community assembly is a fundamental pursuit in microbial ecology, with significant implications for environmental management, biotechnology, and human health. The structure, dynamics, and function of any microbial community are ultimately determined by the complex interplay between environmental conditions, biological interactions, and stochastic processes. This review synthesizes current knowledge on how environmental factors shape community assembly, framing this understanding within the broader context of microbial community composition and structure analysis research. We examine the mechanistic pathways through which abiotic and biotic drivers filter and select for specific microbial taxa, thereby determining community trajectories and ecosystem functioning. By integrating findings from diverse ecosystems—including wastewater treatment, forest soils, and host-associated environments—this guide provides a technical framework for researchers investigating the principles governing microbial assembly patterns across different habitats and scales.

Key Environmental Drivers of Microbial Community Assembly

Environmental factors act as selective filters that determine microbial community composition by favoring taxa with specific functional traits adapted to prevailing conditions. The relative importance of these drivers varies across ecosystems, but several fundamental factors consistently emerge as primary determinants of community structure across diverse habitats.

Table 1: Key Environmental Drivers of Microbial Community Assembly

| Environmental Driver | Mechanism of Influence | Ecosystem Examples | Technical Measurement Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Regulates enzyme kinetics, membrane fluidity, and metabolic rates; selects for thermal adaptation traits | Activated sludge systems, soils, host-associated environments | Amplicon sequencing with temperature covariation analysis; microcosm experiments with temperature gradients |

| pH | Affects membrane potential, nutrient solubility, and enzyme conformation; imposes physiological constraints | Soils, aquatic systems, engineered bioreactors | pH manipulation experiments; biogeographic surveys across natural pH gradients |

| Nutrient Availability | Determines energy and biomass yield; selects for resource acquisition strategies and metabolic pathways | Wastewater treatment, agricultural soils, gut microbiome | Chemical assays (N, P, S); stoichiometric analysis; isotopic tracing |

| Water Availability | Influences osmotic stress, diffusion rates, and cellular hydration; selects for osmoregulation capabilities | Arid soils, hypersaline environments, mucosal surfaces | Water potential measurements; osmolyte profiling; desiccation experiments |

| Toxic Compounds | Creates stress conditions that eliminate sensitive taxa; selects for detoxification and resistance mechanisms | Industrial wastewater, contaminated sites, antibiotic-exposed microbiomes | Toxicity assays; resistance gene quantification; functional enrichment analysis |

| Oxygen Availability | Determines metabolic pathways (aerobic vs. anaerobic); creates redox gradients that partition communities | Sediments, biofilms, gut environments, activated sludge | Microsensor profiling; redox potential measurements; anaerobic cultivation |

Beyond these fundamental abiotic factors, biotic interactions including competition, predation, mutualism, and facilitation further refine community composition by altering the outcome of environmental selection. The physical structure of the environment also plays a crucial role by creating microhabitats with distinct conditions and limiting dispersal, thereby influencing both deterministic and stochastic assembly processes [6] [15] [11].

In wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), for instance, both stochastic factors (e.g., immigration) and deterministic factors (e.g., temperature, nutrients, predation) significantly influence community structure, though their relative contributions vary across systems [6]. Similarly, in forest litter decomposition, climate, litter quality, and microbial communities collectively control decomposition rates, with microbial functional groups (e.g., copiotrophs and oligotrophs) responding differently to these environmental constraints [15].

Methodologies for Investigating Environmental Drivers

Experimental Approaches for Establishing Causality

Determining causal relationships between environmental factors and community assembly requires carefully designed experiments that manipulate driver variables while controlling for confounding factors. Several established protocols enable researchers to disentangle the complex effects of multiple environmental parameters.

Microcosm/Mesocosm Experiments: These controlled system approaches involve manipulating environmental factors in laboratory or semi-natural settings to observe community responses. A typical protocol involves: (1) collecting inoculum from the natural environment; (2) establishing replicate cultures in controlled environments; (3) applying specific environmental treatments (e.g., temperature gradients, nutrient amendments, pH manipulation); (4) monitoring community dynamics over time through sampling; and (5) analyzing compositional and functional changes using molecular methods [15].

Cross-System Comparative Studies: This approach leverages natural environmental gradients to identify relationships between environmental factors and community composition. The MIMICS model calibration study exemplifies this approach, using litterbag decomposition experiments across 10 temperate forest NEON sites to quantify how soil moisture, litter lignin:N ratio, and microbial community composition (represented as copiotroph-to-oligotroph ratio) interact to control decomposition rates [15]. The methodological framework involves: (1) selecting sites across environmental gradients; (2) standardizing sample collection and processing; (3) measuring environmental parameters; (4) characterizing microbial communities; and (5) using statistical modeling to identify driver-response relationships.

Longitudinal Time-Series Analysis: This approach examines how temporal environmental variation influences community dynamics. The WWTP study demonstrating graph neural network prediction of microbial dynamics exemplifies this method, involving 4,709 samples collected over 3-8 years with 2-5 sampling points per month [6]. The protocol includes: (1) high-frequency temporal sampling; (2) standardized DNA extraction and sequencing; (3) precise recording of operational parameters; (4) time-series statistical modeling; and (5) validation of predictions against held-out data.

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Linking Environmental Factors to Community Structure

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Data Outputs | Statistical Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Characterization | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics | Relative abundance tables, Phylogenetic trees, Gene abundance, Functional potential | Diversity indices (alpha, beta), Compositional analysis, Phylogenetic conservation |

| Environmental Measurement | Chemical assays, Sensor networks, Isotopic tracing, Metabolic profiling | Concentration data, Process rates, Reaction norms, Stoichiometric ratios | Correlation analysis, Regression modeling, Multivariate statistics |

| Integration Methods | Mantel tests, Canonical correspondence analysis, Structural equation modeling, Network analysis | Variance partitioning, Path coefficients, Interaction networks, Driver effect sizes | Model selection criteria, Permutation tests, Cross-validation |

Special Considerations for Low-Biomass Environments

Investigating environmental drivers in low-biomass systems requires specialized methodologies to avoid contamination artifacts that can compromise data interpretation. A recent consensus statement outlines essential practices for such studies [16]:

Contamination-Aware Sampling Protocols:

- Decontaminate all sampling equipment using 80% ethanol followed by nucleic acid-degrading solutions

- Use personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, cleansuits, and masks to minimize human-derived contamination

- Include appropriate controls: empty collection vessels, swabs of sampling environment air, and samples of preservation solutions

- Process controls alongside actual samples through all downstream steps to identify contamination sources

DNA Extraction and Sequencing Considerations:

- Use extraction kits specifically designed for low-biomass samples

- Include multiple extraction negative controls

- Utilize DNA-free reagents and consumables

- Apply bioinformatic decontamination tools specifically validated for low-biomass data

These precautions are particularly crucial when studying environments like atmospheric samples, deep subsurface habitats, certain human tissues (respiratory tract, blood), drinking water, and other systems where microbial biomass approaches detection limits [16].

Technical Implementation and Workflows

Data Integration and Modeling Approaches

Modern analysis of environmental drivers in microbial ecology increasingly relies on computational approaches that can handle the high-dimensional, compositionally complex nature of microbiome data. Several advanced modeling frameworks have demonstrated particular utility for elucidating driver-community relationships.

Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models: For predicting microbial community dynamics based on environmental parameters and historical abundance data, GNNs offer a powerful approach. The "mc-prediction" workflow exemplifies this method [6], implementing the following steps: (1) input historical relative abundance data as multivariate time series; (2) apply graph convolution layers to learn interaction strengths between microbial taxa; (3) use temporal convolution layers to extract temporal features across timepoints; (4) employ fully connected neural networks to predict future abundances; (5) validate predictions against held-out data. This approach has successfully predicted species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (2-4 months) in WWTP systems [6].

Process-Based Model Integration: The MIMICS (MIcrobial-MIneral Carbon Stabilization) model represents another approach, integrating empirical microbial data into process-based ecosystem models [15]. The calibration protocol involves: (1) measuring empirical effect sizes for environmental drivers (e.g., soil moisture, litter quality, microbial community composition); (2) setting up the model to provide comparable modeled effect sizes; (3) using Monte Carlo parameterization to calibrate the model to both process rates and their empirical drivers; (4) validating the calibrated model against independent data; (5) projecting responses under future scenarios (e.g., climate change). This approach ensures that models capture not only current system behavior but also the underlying mechanisms governing responses to environmental change.

Visualization Strategies for Communicating Driver-Community Relationships

Effective visualization of microbiome data in the context of environmental drivers requires careful selection of plot types based on the specific research question and data structure [17].

For comparing taxonomic diversity across environmental conditions:

- Alpha diversity: Box plots with jittered data points for group-level comparisons; scatter plots for sample-level visualization

- Beta diversity: Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots with environmental vector overlays for group-level patterns; dendrograms or heatmaps for sample-level relationships

For displaying taxonomic distributions in response to environmental gradients:

- Relative abundance: Stacked bar charts for group-level comparisons; heatmaps for sample-level patterns

- Differential abundance: Bar graphs showing effect sizes across environmental treatments

For identifying core taxa across environmental conditions:

- UpSet plots for comparing taxon intersections across more than three environmental conditions

- Venn diagrams for simpler comparisons (three or fewer conditions)

For visualizing microbial interactions modulated by environmental factors:

- Network plots showing correlation structures under different environmental conditions

- Correlograms displaying relationships between microbial taxa and environmental parameters

All visualizations should be optimized for interpretability by including descriptive titles, clear axis labels, careful color selection (using consistent, color-blind-friendly palettes), and strategic ordering of data (e.g., by median values or environmental gradients) [17].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Analysis

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit, MagAttract PowerSoil DNA Kit | Extracts microbial DNA from complex environmental samples while inhibiting PCR inhibitors | Critical for low-biomass samples; includes inhibition removal technology |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina 16S rRNA gene sequencing panels, Shotgun metagenomics kits | Provides comprehensive profiling of microbial community composition and functional potential | 16S for taxonomic profiling; shotgun for functional capacity assessment |

| PCR Reagents | HotStart Taq DNA polymerase, Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target genes for sequencing; high-fidelity enzymes reduce amplification errors | Choice of polymerase affects error rates and amplification efficiency |

| Bioinformatic Tools | QIIME 2, mothur, DADA2, PICRUSt2 | Processes raw sequencing data; performs diversity analysis; predicts functional potential | Essential for transforming sequence data into ecological insights |

| Statistical Packages | R vegan package, phyloseq, DESeq2 | Performs multivariate statistics, differential abundance testing, and diversity calculations | Enables rigorous statistical testing of environmental driver effects |

| Contamination Controls | DNA-free water, synthetic microbial community standards, extraction blanks | Identifies and quantifies contamination in low-biomass studies | Critical for validating results from low-biomass environments [16] |

Conceptual Framework and Experimental Workflows

The relationship between environmental factors and community assembly follows a logical progression from driver imposition to community response and eventual ecosystem outcome. The diagram below illustrates this conceptual framework:

Conceptual Framework of Ecological Drivers in Microbial Community Assembly

A typical experimental workflow for investigating these relationships integrates field sampling, laboratory processing, and computational analysis, as illustrated below:

Experimental Workflow for Investigating Ecological Drivers

Environmental factors shape microbial community assembly through deterministic selection processes that filter taxa based on their functional traits, while stochastic processes introduce additional variability. The integration of advanced molecular methods with sophisticated computational modeling now enables researchers to not only document these patterns but also predict community responses to environmental change. As research in this field advances, emerging approaches that incorporate empirical microbial data into process-based models, leverage large-scale comparative datasets, and employ machine learning for pattern recognition will further enhance our ability to understand and forecast how environmental drivers structure microbial communities across diverse ecosystems. This knowledge is essential for addressing pressing challenges in environmental management, climate change mitigation, and microbiome-based therapeutics, where predicting and managing microbial community responses to changing conditions is of paramount importance.

The study of microbial communities, or microbiomes, has revolutionized our understanding of life on Earth, from human health to ecosystem functioning. This whitepaper provides a technical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, framed within the broader context of microbial community composition and structure analysis research. The human body harbors approximately 39 trillion bacterial cells, rivaling the number of human cells, with collective microbial genomes containing millions of genes compared to the approximately 23,000 in the human genome [18] [19]. This genetic complexity enables microbiomes to influence processes ranging from ecosystem biogeochemistry to cancer pathogenesis and response to immunotherapy.

Advancements in sequencing technologies and computational methods have enabled high-resolution analysis of microbial communities across diverse habitats. This document presents a comparative analysis of three critical microbiome niches: the human gut, environmental ecosystems (specifically wastewater treatment plants), and cancer-associated microbial communities. By examining their structural features, functional roles, and analytical approaches, this guide aims to equip researchers with the methodological frameworks needed to advance microbiome science across basic and applied research domains, particularly in therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Communities

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of Major Microbiome Types

| Feature | Human Gut Microbiome | Environmental Microbiome (Wastewater Treatment) | Cancer-Associated Microbiome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Microbial Abundance | ~100 trillion microorganisms [19] | Varies by plant size; 52-65% of DNA sequences from top 200 ASVs in Danish WWTPs [6] | Low biomass; heterogeneous distribution [20] |

| Key Dominant Taxa | Bacteroides, Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium [18] [19] | Polyphosphate accumulating organisms (PAOs), Glycogen accumulating organisms (GAOs), Filamentous bacteria [6] | Fusobacterium spp. (OSCC), Helicobacter pylori (gastric), Akkermansia muciniphila (multiple cancers) [18] [21] |

| Diversity Metrics | Shannon/Simpson/Chao1 indices; Higher diversity correlates with better psychological well-being (zr = 0.215) [19] | Bray-Curtis dissimilarity; Mean Absolute Error; Mean Squared Error for predictive models [6] | Varies by cancer type; often reduced diversity with specific pathogen enrichment [18] [20] |

| Primary Functions | Metabolism, immune regulation, neuroendocrine signaling, drug metabolism [18] [19] | Pollutant removal, nutrient cycling, energy recovery [6] | Modulating TME, affecting therapy response, promoting chronic inflammation [18] [21] |

| Influencing Factors | Diet, age, medications, genetics, lifestyle [18] [19] | Temperature, nutrients, predation, immigration, operational parameters [6] | Tumor type, immune status, compromised mucosal barriers [18] [20] |

Table 2: Impact of Specific Microbial Taxa on Cancer Immunotherapy

| Microbial Taxon | Cancer Type | Impact on Therapy | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium spp. | Melanoma, NSCLC | Enhanced anti-PD-1/PD-L1 efficacy [21] | Dendritic cell maturation, enhanced CD8+ T cell activity [21] |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | NSCLC, RCC, HCC | Improved anti-PD-1 response [21] | Modulation of immune cell infiltration in TME [21] |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Melanoma | Restored anti-CTLA-4 efficacy [21] | Th1 cell activation in tumor-draining lymph nodes [21] |

| Faecalibacterium | Multiple cancers | Generally compromised in aged adults [18] | Production of anti-inflammatory metabolites like butyrate [18] |

| Fusobacterium spp. | Colorectal cancer, OSCC | Cancer progression and therapy resistance [18] | DNA damage, chronic inflammation, mucosal barrier disruption [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Microbial Community Profiling Techniques

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: This amplicon-based approach remains the gold standard for microbial community structural analysis due to its cost-effectiveness and well-established bioinformatics pipelines [20]. The protocol involves: (1) DNA extraction from samples using bead-beating or enzymatic lysis protocols; (2) Amplification of hypervariable regions (V3-V4) using primer pairs (e.g., 341F/806R); (3) Library preparation and sequencing on Illumina platforms; (4) Bioinformatic processing including quality filtering, ASV/OTU clustering, taxonomic classification using reference databases (Silva, Greengenes, or ecosystem-specific databases like MiDAS 4 for wastewater samples) [6] [20]. This method provides robust community composition data but limited functional information.

Shotgun Metagenomics: For functional potential assessment, shotgun metagenomics sequences all genomic DNA in a sample [20]. The protocol includes: (1) High-quality DNA extraction; (2) Library preparation without target-specific amplification; (3) High-throughput sequencing on Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore platforms; (4) Computational analysis including quality control, assembly, binning, gene prediction, and functional annotation using databases like KEGG, COG, and eggNOG [20]. This approach provides species-level resolution and insights into functional potential but requires higher sequencing depth and computational resources.

Microbial Single-Cell Sequencing: To address microbial heterogeneity, emerging techniques like microSPLiT and smRandom-seq2 enable transcriptome profiling at single-microbe resolution [20]. The workflow involves: (1) Sample dissociation and single-cell encapsulation; (2) Cell lysis and mRNA capture; (3) Reverse transcription and library preparation; (4) Sequencing and bioinformatic analysis to identify cellular subpopulations and rare cell states [20]. This method reveals functional heterogeneity but requires specialized equipment and expertise.

Predictive Modeling of Microbial Dynamics

Graph Neural Network (GNN) Approach: A recently developed methodology for predicting microbial community dynamics uses historical relative abundance data to forecast future compositions [6]. The "mc-prediction" workflow implements the following steps: (1) Data preprocessing and normalization of time-series data; (2) Pre-clustering of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) using graph network interaction strengths or ranked abundances; (3) Model training with moving windows of 10 consecutive samples as input; (4) Graph convolution layer to learn ASV interaction strengths; (5) Temporal convolution layer to extract temporal features; (6) Output layer with fully connected neural networks to predict future relative abundances [6]. This approach has successfully predicted species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (2-4 months) in wastewater treatment plants and human gut microbiomes.

Spatial Analysis of Tumor Microbiome

Spatial Transcriptomics with Microbiome Mapping: To understand the spatial distribution of microbes within the tumor microenvironment, an integrated approach combines: (1) Tissue sectioning and spatial barcoding using 10x Visium platform; (2) Hybridization capture of microbial transcripts; (3) In situ sequencing; (4) Computational deconvolution of host and microbial signals; (5) Correlation with histopathological features [20]. This methodology has revealed that bacterial communities in tumors are distributed across highly immunosuppressive microecological landscapes.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Signaling Pathways in Cancer-Associated Microbiome

Figure 1: Microbial Modulation of Cancer Signaling. Intratumoral microbes activate multiple signaling pathways including TLRs, STING, NF-κB, ERK, and WNT/β-catenin through microbial components and metabolites, promoting inflammation, proliferation, immune evasion, and metastasis [20].

Predictive Modeling Workflow

Figure 2: Microbial Community Prediction Workflow. GNN-based prediction workflow using historical abundance data to forecast future microbial community structures through preprocessing, clustering, and temporal modeling [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Primers (341F/806R) | Amplification of hypervariable regions for bacterial community profiling | Human gut, environmental, and intratumoral microbiome characterization [6] [20] |

| MiDAS 4 Database | Ecosystem-specific taxonomic classification reference | Species-level classification of wastewater treatment plant microbiomes [6] |

| SPRi-based Barcoding Beads | Single-cell encapsulation and mRNA capture for microbial transcriptomics | Identification of functional heterogeneity in bacterial subpopulations using microSPLiT [20] |

| Graph Neural Network Framework | Modeling relational dependencies in multivariate time series data | Predicting future microbial community structure in WWTPs and human gut [6] |

| Spatial Barcoding Slides (10x Visium) | In situ capture of transcriptomic data with spatial coordinates | Mapping microbial communities within tumor microenvironments [20] |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) Material | Microbial community transfer between donors and recipients | Overcoming immunotherapy resistance in melanoma patients [21] |

| CB-7921220 | CB-7921220, MF:C14H12N2O2, MW:240.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ZEN-2759 | ZEN-2759, MF:C17H16N2O2, MW:280.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comparative analysis demonstrates both shared principles and unique characteristics across human gut, environmental, and cancer-associated microbiomes. While all microbial communities follow ecological principles of diversity, succession, and environmental response, their specific compositions, functions, and applications differ significantly. The human gut microbiome exhibits remarkable plasticity in response to dietary interventions and represents a promising therapeutic target for enhancing cancer immunotherapy outcomes [21]. Environmental microbiomes, such as those in wastewater treatment systems, demonstrate predictable dynamics that can be modeled for process optimization [6]. Cancer-associated microbiomes present unique configurations that influence disease progression and treatment response, offering novel diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities [18] [20].

Emerging technologies including single-cell microbiome sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and graph neural network-based predictive models are advancing our capacity to understand and manipulate these complex communities. As the field progresses, integrating multi-omics data with advanced computational models will be essential for translating microbiome research into clinical applications and environmental solutions. The global microbiome market, projected to reach $1.52 billion by 2030, reflects the growing recognition of these microbial communities as fundamental drivers of health, disease, and ecosystem functioning [22].

Advanced Analytical Techniques: From Laboratory Methods to Computational Modeling

The analysis of microbial community composition and structure is a cornerstone of modern microbiology, enabling advancements in human health, agriculture, and environmental science. The choice of sequencing methodology profoundly influences the resolution, depth, and biological insights attainable from any microbiome study. Two principal high-throughput sequencing approaches have emerged as critical technologies for taxonomic profiling: 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suited for different research objectives and resource constraints. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these foundational methods, detailing their experimental protocols, analytical capabilities, and performance characteristics to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal approach for their specific investigative needs.

16S rRNA gene sequencing (metataxonomics) employs polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) of the bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA gene, which are then sequenced, typically using Illumina short-read or Nanopore/PacBio long-read platforms [23] [24]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomic sequencing is an untargeted approach that involves randomly fragmenting and sequencing all DNA present in a sample, enabling simultaneous identification of bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms without amplification biases [23] [25].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of 16S rRNA Sequencing vs. Shotgun Metagenomics

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Target | Specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene [23] | All genomic DNA in a sample [23] |

| Taxonomic Scope | Limited to Bacteria and Archaea [23] | Comprehensive: Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Eukaryotes [23] [26] |

| Typical Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (short-read); Species-level with full-length [24] | Species to Strain-level [26] |

| Functional Potential | Not available (must be inferred) | Direct characterization of functional genes and pathways [27] [28] |

| Relative Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Computational Demand | Lower | Higher, requires extensive bioinformatics resources [26] |

| Primary Biases | Primer selection, PCR amplification [29] | Database completeness, host DNA contamination [26] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Comparative Studies

| Performance Metric | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Power | Detects only part of the community, biased towards abundant taxa [29] [26] | Higher power to identify less abundant taxa with sufficient reads [29] | Chicken gut microbiota study [29] |

| Significant Genera (Caeca vs. Crop) | 108 | 256 | Same chicken gut dataset analyzed with both methods [29] |

| Alpha Diversity | Lower, sparser data [26] | Higher, detects more species [26] | Human colorectal cancer stool samples [26] |

| Abundance Correlation | Positive correlation for shared taxa, but 16S can miss low-abundance genera [29] | More complete abundance profile | Genus-level comparison [29] [26] |

| Species-Level Resolution | Challenging with short reads; improved with full-length sequencing [24] | Reliable species and strain-level discrimination [26] | Human gut microbiome analysis [26] [24] |

Experimental Protocols

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow

A. DNA Extraction: The initial step is crucial for obtaining high-quality, unbiased microbial DNA. Kits specifically designed for complex samples (e.g., soil, stool) are recommended, such as the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN) or the NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel) [26] [30]. These kits efficiently lyse diverse microbial cell walls and remove PCR inhibitors like humic acids. The inclusion of bead-beating is essential for breaking down tough cell walls.

B. Library Preparation (Illumina Short-Read):

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target hypervariable region (e.g., V3-V4) using universal primer sets (e.g., 341F/805R) [26]. The number of PCR cycles (typically 25-35) should be minimized to reduce amplification bias [30].

- Attachment of Indices and Adapters: A second, limited-cycle PCR step is used to attach unique dual indices and sequencing adapters to the amplicons.

- Library Validation: The final library is purified and quantified using fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) and its size distribution verified with a Fragment Analyzer or Bioanalyzer [31].

C. Library Preparation (Nanopore Full-Length):

- Full-Length PCR: Amplify the nearly complete 16S rRNA gene (~1500 bp) using primers such as 27F and 1492R [24].

- Barcoding: Purified amplicons are ligated to native barcodes using a kit like the Native Barcoding Kit 96 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) [31].

- Adapter Ligation: Sequencing adapters are ligated to the barcoded amplicons to facilitate their loading onto the flow cell.

- Sequencing: The library is loaded onto a MinION device using an R9.4.1 or newer flow cell for sequencing [30] [24].

D. Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Short-Read (DADA2/QIIME2): Raw reads are quality-filtered, trimmed, denoised, and merged to create Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). Taxonomy is assigned using reference databases like SILVA or Greengenes [26] [24].

- Long-Read (Emu): Tools like Emu are designed for the error-profile of Nanopore reads and perform taxonomic assignment without constructing ASVs, often using a curated default database [31] [24].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

A. DNA Extraction & Quality Control: This requires high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. The same kits as for 16S sequencing are used, but with extra care to minimize shearing. DNA quantity and quality are critical and are assessed via Qubit and agarose gel electrophoresis [25] [26].

B. Library Preparation:

- Fragmentation: Genomic DNA is randomly sheared to a target size of 300-800 bp via mechanical shearing (e.g., sonication) or enzymatic digestion.

- End-Repair and dA-Tailing: DNA fragments are enzymatically treated to create blunt ends, followed by the addition of an 'A' base to the 3' end.

- Adapter Ligation: Sequencing adapters, including sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing, are ligated to the fragments.

- Library Amplification & Clean-up: The adapter-ligated fragments are PCR-amplified (typically 4-10 cycles) and purified. The final library is quantified and its size distribution validated [25] [26].

C. Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced on high-throughput platforms like the Illumina NovaSeq or PacBio Sequel IIe to generate tens of millions of reads per sample for sufficient coverage [25].

D. Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Quality Control & Host Removal: Tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic are used for quality control. Reads mapping to the host genome (e.g., human, cow) are removed using Bowtie2 [25] [26].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Reads are aligned to comprehensive genomic databases (e.g., GTDB, NCBI RefSeq) using tools like Meteor2 or MetaPhlAn4 to estimate taxonomic abundances [27] [26]. Meteor2 leverages environment-specific microbial gene catalogues for high sensitivity, particularly for low-abundance species [27].

- Functional Profiling: Reads are mapped to functional databases (e.g., KEGG, CAZy, CARD) using tools like HUMAnN3 or the integrated pipeline in Meteor2 to reconstruct metabolic pathways and identify antibiotic resistance genes [27] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Metagenomic Sequencing

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Lyses microbial cells and purifies DNA from complex samples while removing inhibitors. | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN) [30], NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel) [26], Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit (Zymo Research) [31] |

| PCR Enzymes | Amplifies the target 16S rRNA gene region or adds full-length adapters in shotgun library prep. | High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5, KAPA HiFi) |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Universal primer sets targeting specific hypervariable regions for amplification. | 341F/805R (for V3-V4) [26], 27F/1492R (for full-length) [24] |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares DNA fragments for sequencing by end-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and indexing. | Illumina DNA Prep, Oxford Nanopore Native Barcoding Kit [31] |

| Mock Community Standard | Validates the entire workflow, from DNA extraction to bioinformatics, assessing accuracy and bias. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (D6300/D6305/D6331) [31] [30] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | For processing raw data, taxonomic profiling, and functional analysis. | DADA2 [26], QIIME2 [24], Emu [24], Meteor2 [27], MetaPhlAn4 [27], HUMAnN3 [27] |

| Reference Databases | Curated collections of genomic or gene sequences for taxonomic and functional assignment. | SILVA [26] [24], GTDB [27], KEGG [27], CARD [28] |

| Brezivaptan | Brezivaptan, CAS:1370444-22-6, MF:C25H30ClN5O3, MW:484.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-OMe-UDP | 5-OMe-UDP, MF:C10H16N2O13P2, MW:434.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Technologies

The choice of sequencing method directly impacts the ability to discover biologically meaningful patterns and biomarkers. For instance, in a study on colorectal cancer (CRC), full-length 16S rRNA sequencing with Nanopore's R10.4.1 chemistry enabled species-level identification of established CRC biomarkers like Parvimonas micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum, which were less distinctly resolved with short-read Illumina V3-V4 sequencing [24]. Similarly, shotgun sequencing's capacity to profile the entire community revealed discriminative patterns in less abundant genera that 16S sequencing failed to detect [29].

Furthermore, shotgun sequencing unlocks functional insights. As demonstrated in a study of postpartum dairy cows, shotgun data allowed researchers to not only identify pathogenic bacteria associated with clinical endometritis but also to find that the Wnt/catenin signaling pathway had a lower abundance in diseased cows compared to healthy ones [25]. In environmental microbiology, shotgun metagenomics has been used to reveal how crop rotation practices alter the rhizosphere microbiome and to uncover the dynamics of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in fungal-dominated environments [28] [32].

Both 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics provide powerful yet distinct lenses for examining microbial communities. 16S rRNA sequencing remains a robust, cost-effective choice for large-scale studies focused on bacterial and archaeal composition, particularly when genus-level resolution is adequate or sample biomass is low. The advent of full-length 16S sequencing with third-generation platforms is steadily closing the resolution gap at the species level. Shotgun metagenomics, while more resource-intensive, offers an unparalleled, comprehensive view of the microbiome by delivering high-resolution taxonomic profiling across all domains of life and directly characterizing the community's functional potential.

The decision between these methods is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is optimal for a specific research question, experimental context, and resource framework. As sequencing costs continue to decline and analytical tools like Meteor2 become more sophisticated and accessible, shotgun metagenomics is poised to become the standard for holistic microbiome analysis, especially in clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development where strain-level tracking and functional insights are critical.

High-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the study of microbial communities, enabling researchers to move beyond culture-dependent methods to comprehensively analyze complex microbial ecosystems. Within microbial community composition and structure research, these technologies allow for unprecedented resolution in profiling taxonomic membership, functional potential, and metabolic activities. Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology forms the backbone of modern microbial ecology investigations, providing the accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness required for population-scale studies [33] [34].

The application of high-throughput sequencing in microbiome research presents unique experimental design challenges that distinguish it from conventional molecular biology approaches. Microbial communities are dynamic entities influenced by host factors, environmental exposures, and technical variability throughout the sequencing workflow [35]. Understanding the capabilities of different Illumina platforms, along with appropriate experimental frameworks, is therefore essential for generating meaningful biological insights into microbial community assembly, structure, and function.

Illumina Sequencing Platform Specifications and Selection

Illumina offers a range of sequencing platforms categorized into benchtop and production-scale systems, each with distinct throughput, runtime, and application capabilities. Selecting the appropriate platform depends on the scale of the microbial study, desired sequencing depth, and specific research questions being addressed.

Table 1: Comparison of Benchtop Sequencing Platforms

| Specification | iSeq 100 System | MiSeq System | NextSeq 1000/2000 Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max output per flow cell | 30 Gb | 120 Gb | 540 Gb |

| Run time (range) | ~4–24 hours | ~11–29 hours | ~8–44 hours |

| Max reads per run (single reads) | 100M | 400M | 1.8B |

| Max read length | 2 × 500 bp | 2 × 150 bp | 2 × 300 bp |

| Key microbial applications | 16S metagenomic sequencing, small whole-genome sequencing (microbe, virus) | 16S metagenomic sequencing, metagenomic profiling, small whole-genome sequencing | Metagenomic profiling (shotgun), whole-genome sequencing, metatranscriptomics |

Table 2: Comparison of Production-Scale Sequencing Platforms

| Specification | NextSeq 2000 System | NovaSeq 6000 System | NovaSeq X Plus System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max output per flow cell | 540 Gb | 3 Tb | 8 Tb |

| Run time (range) | ~8–44 hours | ~13–44 hours | ~17–48 hours |

| Max reads per run (single reads) | 1.8B | 20B (dual flow cells) | 52B (dual flow cells) |

| Max read length | 2 × 300 bp | 2 × 250 bp | 2 × 150 bp |

| Key microbial applications | Metagenomic profiling, large whole-genome sequencing | Large whole-genome sequencing, metagenomic profiling | Large whole-genome sequencing, metagenomic profiling at production scale |

For large-scale microbial ecology studies requiring extensive sequencing depth, such as population-level microbiome surveys or meta-analyses, production-scale systems like the NovaSeq X Series provide the necessary throughput [33]. The NovaSeq X Plus System delivers up to 16 Tb output and 52 billion single reads per dual flow cell run, enabling unprecedented scale in microbial community profiling [33]. Benchtop systems like the MiSeq and NextSeq 1000/2000 are ideal for targeted amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA gene) and smaller metagenomic studies [36].

Experimental Design for Microbial Community Studies

Foundational Considerations for Multi-Omic Approaches

Robust experimental design in microbial community research requires careful consideration of the specific research questions, available samples, and appropriate sequencing technologies. Multi-omic approaches that combine genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data provide a more comprehensive understanding of microbial community structure and function [33] [35]. Different technologies measure distinct aspects of microbial communities: 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing reveals phylogenetic composition; shotgun metagenomics characterizes functional genetic potential; metatranscriptomics profiles gene expression; and metabolomics identifies bioactive compounds [35].

A critical consideration in microbial experimental design is recognizing that the strain serves as the fundamental epidemiological unit [35]. Significant genomic and functional variation exists within microbial species, with profound implications for host health. For example, Escherichia coli encompasses neutral commensals, pathogenic strains, and probiotics, with a pangenome exceeding 16,000 gene families [35]. Strain-level resolution requires sufficient sequencing depth and appropriate bioinformatic tools to discriminate closely related organisms, which can be achieved through both amplicon and shotgun metagenomic approaches with careful optimization [35].

Two-Stage Study Design and Sample Selection

Microbial community studies can be efficiently designed using a two-stage approach that combines initial broad surveying with targeted follow-up investigations [37]. This strategy involves first conducting a high-level survey of many samples (e.g., using 16S amplicon sequencing) followed by selecting subsets for more intensive multi-omic characterization (e.g., metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, or metabolomic profiling) [37].

Purposive sample selection methods for follow-up stages include:

- Representative sampling: Selecting samples typical of the initially surveyed population

- Diversity maximization: Targeting communities with high microbial diversity

- Extreme/deviant community sampling: Focusing on outliers with unusual characteristics

- Phenotype-discriminant sampling: Identifying communities that distinguish among environmental or host phenotypes

- Rare species targeting: Specifically investigating communities containing low-abundance taxa

Each selection approach influences the resulting sample set characteristics, with only representative sampling minimizing differences from the original microbial survey [37]. Diversity maximization, in particular, can result in strongly non-representative follow-up samples [37]. Implementation tools like microPITA (Microbiomes: Picking Interesting Taxa for Analysis) facilitate two-stage study design for microbial communities [37].

Special Considerations for Metatranscriptomics

Metatranscriptomic RNA sequencing presents unique experimental challenges as it captures the dynamically expressed gene repertoire of microbial communities under specific conditions [35]. Key considerations include:

- Sample preservation: Methods must maintain RNA integrity, requiring immediate stabilization upon collection [35]

- Timing: Samples are highly sensitive to exact collection circumstances and temporal dynamics [35]

- Paired metagenomes: Metatranscriptomes should be accompanied by metagenomic data to differentiate changes in gene expression from variations in DNA copy number (microbial growth) [35]

- Technical variability: RNA extraction protocols are particularly sensitive to technical artifacts and require rigorous standardization [35]

Sequencing Data Quality and Analysis

Quality Metrics and Their Impact on Data Interpretation

Sequencing quality scores are critical for assessing data reliability in microbial community studies. The quality score (Q) follows a phred-like algorithm where Q = -10logâ‚â‚€(e), with 'e' representing the estimated probability of an incorrect base call [34]. Key quality benchmarks include:

- Q20: 1 in 100 error rate (99% accuracy)

- Q30: 1 in 1000 error rate (99.9% accuracy) - considered the benchmark for high-quality NGS [34]

Lower quality scores can render significant portions of reads unusable and increase false-positive variant calls, potentially leading to inaccurate biological conclusions about microbial community composition [34]. For Illumina systems, the majority of bases typically score Q30 and above, providing confidence in downstream analyses such as single-nucleotide variant (SNV) calling for strain-level discrimination [35] [34].

Bioinformatics and Data Management

High-throughput microbial community studies generate massive datasets requiring sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines and data management strategies. Illumina's DRAGEN (Dynamic Read Analysis for GENomics) platform provides secondary analysis capabilities, processing an entire human genome at 30x coverage in approximately 25 minutes [33]. For larger microbial ecology studies, comprehensive platforms like Illumina Connected Analytics offer cloud-based data management, enabling researchers to aggregate, explore, and share large volumes of multi-omic data in a secure, scalable environment [33].

Data analysis considerations for microbial community studies include:

- Software licenses and compute resources: Adequate computational infrastructure is essential for processing complex metagenomic datasets

- Storage solutions: Sequencing data requires substantial storage capacity, often necessitating compression and archiving strategies

- Analysis pipeline scalability: Bioinformatics workflows must handle increasing data volumes as studies expand

- Multi-omic integration tools: Specialized software is needed to combine taxonomic, functional, and expression data

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Innovation Roadmap for Microbial Community Analysis

Illumina's technology innovation roadmap includes several developments with significant implications for microbial community research:

Constellation mapped read technology (Estimated 1H 2026): This approach uses a simplified NGS workflow with on-flow cell library preparation and cluster proximity information, enabling enhanced mapping of challenging genomic regions, ultra-long phasing, and improved detection of large structural rearrangements without compromising short-read accuracy [38]

Spatial transcriptomics (Estimated 1H 2026): This technology will capture poly(A) RNA transcripts on an advanced substrate, allowing hypothesis-free analysis of gene expression profiling with spatial context in complex microbial environments like biofilms or host tissues [38]

5-base solution for methylation studies: Available in 2025, this novel chemistry simultaneously detects genetic variants and methylation patterns in a single assay by converting 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to thymine (T), enabling integrated genomic and epigenomic characterization of microbial communities [38]

Multi-omic data analysis platforms (Estimated 2H 2025): These will enable researchers to combine different data types (transcriptomics, proteomics, etc.) and support multimodal analysis including spatial and single-cell data through streamlined bioinformatic pipelines [38]

Comparative Platform Performance

As new sequencing technologies emerge, performance comparisons become essential for platform selection. In a comparative analysis of whole-genome sequencing performance, the Illumina NovaSeq X Series demonstrated several advantages over the Ultima Genomics UG 100 platform [39]:

- 6× fewer SNV errors and 22× fewer indel errors compared to the UG 100 platform when assessed against the full NIST v4.2.1 benchmark [39]

- Comprehensive genome coverage without excluding challenging regions, whereas the UG 100 platform masks 4.2% of the genome where performance is poor [39]

- Superior performance in GC-rich regions and homopolymers longer than 10 base pairs, which are often functionally important in microbial genomes [39]

- More accurate variant calling in biologically relevant genes, including those with associations to disease [39]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Sequencing

| Reagent/Category | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| NovaSeq X Series 10B Reagent Kit | High-intensity sequencing applications on production-scale systems for large microbial community studies [39] |