A Comprehensive Guide to 16S rRNA and ITS Amplicon Sequencing for Microbial Community Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing for profiling bacterial and fungal communities.

A Comprehensive Guide to 16S rRNA and ITS Amplicon Sequencing for Microbial Community Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing for profiling bacterial and fungal communities. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and diverse applications from environmental monitoring to clinical diagnostics. The content delves into critical troubleshooting aspects, including primer selection, contamination control, and data analysis optimization, and concludes with a comparative evaluation of emerging techniques and bioinformatics tools to ensure taxonomic accuracy and biological relevance in microbiome studies.

Core Principles and Scope of Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

In the field of microbial ecology, understanding the composition and dynamics of microbial communities is essential across diverse environments—from the human gut to industrial bioreactors. Targeted amplicon sequencing has emerged as a foundational method for such investigations, enabling researchers to determine the taxonomic makeup of complex microbial samples by sequencing specific marker genes [1] [2]. This approach focuses on amplifying and sequencing a particular gene or genomic region of interest, bypassing the need for culturing, which historically captured only a very small subset of easily culturable bacteria [2].

The most commonly targeted genes for this purpose are the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene for bacteria and archaea, and the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region for fungi [1]. The 16S rRNA gene, approximately 1,550 base pairs long, contains nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that provide taxonomic signatures for distinguishing different organisms, interspersed with conserved regions that allow for the design of universal PCR primers [3] [4] [5]. Similarly, the ITS regions, located between the 18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNA genes in fungi, offer high sequence variability for differentiating fungal species [1]. This targeted method provides a powerful balance between comprehensive community profiling and cost-effective, high-throughput sequencing, making it an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand microbiome relationships in health, disease, and various ecosystems.

Core Principles and Marker Gene Selection

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The 16S rRNA gene is a highly conserved genetic marker found in all prokaryotic organisms (bacteria and archaea), encoding the RNA component of the 30S ribosomal subunit [4] [1]. Its utility in microbial taxonomy and phylogenetics stems from several key properties: it is universally distributed across prokaryotes, contains sufficiently conserved sequences for primer design, and possesses variable regions that accumulate mutations at different rates, providing phylogenetic resolution at multiple taxonomic levels [4] [2]. The gene functions as a "molecular chronometer" for measuring evolutionary relationships, with the degree of sequence conservation reflecting its critical role in protein synthesis—a fundamental cellular process [4].

The structure of the 16S rRNA gene includes nine variable regions (V1-V9) interspersed throughout highly conserved sequences [3] [5]. These variable regions evolve at different rates, with some offering better discrimination for specific taxonomic groups than others. For example, the V4 region is widely used for its balanced characteristics, while the V1-V2 and V3-V4 regions often provide superior resolution for certain bacterial phyla [3] [5]. The conserved regions enable researchers to design "universal" PCR primers that can amplify the 16S gene from a broad range of microorganisms, while the variable regions provide the sequence diversity necessary for taxonomic classification [2].

ITS Region Sequencing

For fungal community analysis, the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) regions represent the marker of choice. The ITS lies between the rRNA genes in fungal genomes, comprising two non-coding spacers: ITS1 (between 18S and 5.8S rRNA genes) and ITS2 (between 5.8S and 28S rRNA genes) [1]. Unlike the coding regions of rRNA genes, these spacers evolve rapidly and exhibit significant sequence divergence even between closely related fungal species, making them ideal for species-level identification [1].

The ITS1 and ITS2 regions are relatively small (approximately 350 bp and 400 bp, respectively), making them well-suited for high-throughput sequencing platforms while containing sufficient variation for discriminating between fungal taxa [1]. Fungal ITS sequencing has become the standard method for mycobiome studies across diverse environments, from clinical samples to agricultural and industrial settings. The compact nature of these regions facilitates amplification and sequencing from complex samples, while established reference databases enable robust taxonomic assignment.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparison of Marker Genes for Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

| Feature | 16S rRNA Gene | ITS Region |

|---|---|---|

| Target Organisms | Bacteria and Archaea | Fungi |

| Genetic Location | Chromosomal (multiple copies) | Between rRNA genes (non-coding) |

| Length | ~1,550 bp | ITS1: ~350 bp; ITS2: ~400 bp |

| Copy Number Variation | 1-21 copies per genome [6] | ~100 copies [1] |

| Primary Application | Bacterial community profiling | Fungal community profiling |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus to species level (strain level with full-length) [5] | Species to strain level |

| Key Advantage | Extensive reference databases | High interspecies variability |

| Main Limitation | Intragenomic heterogeneity [5] | Lack of universal primers for all fungi |

Experimental Design and Workflow Considerations

Variable Region Selection

The choice of which 16S rRNA variable region to sequence represents a critical decision point in experimental design, as this selection significantly influences the resulting taxonomic profile [3]. Different variable regions exhibit varying degrees of discrimination power for specific bacterial taxa, meaning that primer choice can determine which organisms are detected—and with what accuracy—in a complex community [3] [5].

Recent comparative studies have demonstrated that full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing provides the highest taxonomic resolution, potentially discriminating between closely related species and even strains [5]. However, when technical or budgetary constraints necessitate targeting specific variable regions, different sub-regions show distinct performance characteristics. The V4 region is among the most commonly used but may fail to provide species-level classification for many taxa, while regions such as V1-V2 and V3-V4 often offer improved discrimination for specific bacterial groups [3] [5].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Commonly Used 16S rRNA Variable Regions

| Target Region | Recommended Primers | Taxonomic Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | 27F-338R [3] | Good for Proteobacteria [5] | May miss Bacteroidetes [3] |

| V3-V4 | 341F-785R [3] | Effective for many human gut taxa | Lower resolution for Actinobacteria [5] |

| V4 | 515F-806R [3] | Broad applicability, well-established | Poor species-level discrimination (56% failure rate) [5] |

| V4-V5 | 515F-944R [3] | Good for specific environments | May miss Bacteroidetes [3] |

| V6-V8 | 939F-1378R [3] | Effective for Clostridium and Staphylococcus [5] | Less commonly used, smaller reference databases |

| Full-length (V1-V9) | 27F-1492R | Highest taxonomic resolution [5] | Requires long-read sequencing platforms |

Sample Collection and Preservation

Robust microbiome research begins with appropriate sample collection and preservation techniques to minimize technical artifacts and preserve authentic community structures. For microbial community analysis, sample types can range from water, soil, and stool to swabs (oral, skin, nasal) and tissue biopsies [1] [2]. Each sample type presents unique challenges for maintaining microbiome integrity during collection and storage.

Rapid stabilization of microbial communities is essential, as continued metabolic activity or DNA degradation can alter community profiles. For DNA-based analyses, immediate freezing at -80°C or use of specialized preservation buffers that inactivate nucleases and prevent bacterial growth is recommended [2]. For RNA-based approaches, which target the active microbiota, even more rapid processing is necessary due to the lability of RNA molecules [6]. The biomass level of samples should also be considered, with low-biomass samples (such as uterine cytobrush samples) requiring extra precautions to avoid contamination from reagents or the environment [6].

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

DNA extraction methods must be selected based on the sample type and the microbial groups of interest, as different protocols exhibit varying efficiencies for Gram-positive versus Gram-negative bacteria, or for organisms with tough cell walls [7]. The goal is to achieve comprehensive cell lysis while minimizing shearing of DNA and avoiding co-purification of inhibitors that could compromise downstream PCR.

For library preparation, the first step involves targeted amplification of the marker gene region using primers that incorporate platform-specific sequencing adapters and barcodes [3] [7]. The use of unique barcode sequences for each sample enables multiplexing—pooling numerous samples in a single sequencing run—which dramatically reduces per-sample costs [2]. For challenging samples with high host DNA contamination (such as coral tissues), additional steps such as peptide nucleic acid (PNA) clamps may be employed to suppress amplification of host sequences [7]. The number of PCR cycles should be minimized to reduce the introduction of amplification biases, particularly for low-biomass samples where over-amplification can distort community representations [7] [6].

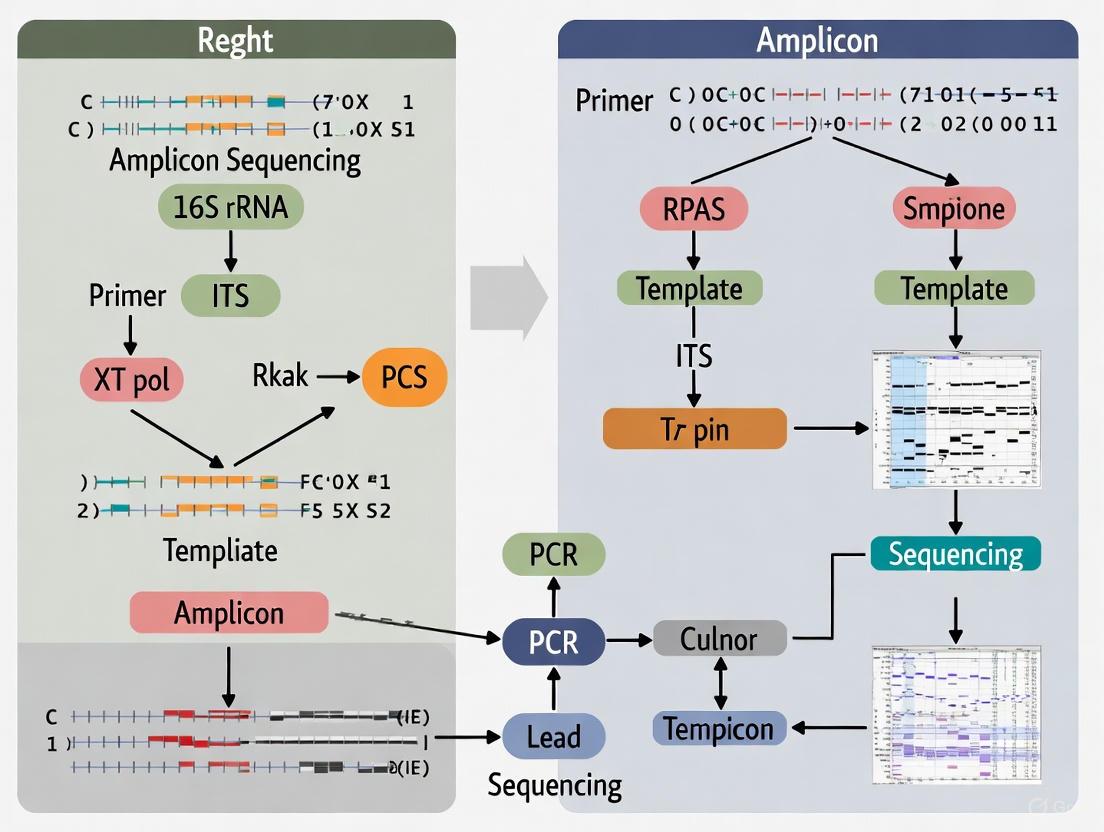

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing studies, from sample collection through data analysis.

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipelines

Sequence Processing and Clustering

The analysis of amplicon sequencing data begins with quality control and preprocessing of raw sequence reads. This typically involves merging paired-end reads (when using Illumina platforms), quality filtering to remove low-quality sequences, dereplication (collapsing identical sequences), and removing chimeric sequences—artifactual amplicons formed during PCR from multiple parent sequences [8]. These steps are crucial for reducing technical noise before biological interpretation.

Processed sequences are then grouped into taxonomic units using either Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). OTU clustering groups sequences based on a similarity threshold (traditionally 97%), assuming that sequencing errors and minor variations can be collapsed into a single unit [3] [8]. In contrast, ASV methods (also called zOTUs or ESVs) employ denoising algorithms to distinguish biological sequences from sequencing errors, resulting in units that differ by as little as a single nucleotide [3] [8]. ASV approaches (e.g., DADA2, Deblur) generally provide higher resolution and greater reproducibility across studies, while OTU methods (e.g., UPARSE, mothur) may be more robust to sequencing errors in some contexts [8].

Taxonomic Assignment and Diversity Analysis

Taxonomic classification assigns biological identities to OTUs or ASVs by comparing them to reference databases of known microbial sequences. Commonly used databases include GreenGenes (GG), Silva, the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP), and specialized databases for particular environments [3]. The choice of database significantly influences results, as variations in nomenclature, taxonomy, and sequence coverage can lead to different taxonomic assignments for the same sequence [3].

Downstream analysis typically includes measures of alpha diversity (within-sample diversity) and beta diversity (between-sample diversity). Alpha diversity metrics (e.g., Chao1, Simpson index) provide insights into community richness and evenness, while beta diversity measures (e.g., Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, UniFrac distance) enable comparison of community structures across different samples or experimental conditions [8]. These analyses form the basis for identifying statistically significant differences in microbial communities between experimental groups—a key objective in many microbiome studies.

Figure 2: Bioinformatic processing pipeline for 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing data.

Applications Across Research Fields

Medical and Pharmaceutical Applications

In medical research, 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing have revolutionized our understanding of the human microbiome's role in health and disease. These approaches have been used to investigate microbiome associations with metabolic diseases, digestive disorders, autoimmune conditions, neurological diseases, and various cancers [9] [1]. The high sensitivity of these methods enables detection of low-abundance pathogens or dysbiotic communities that may contribute to disease pathogenesis.

In drug development, microbiome analysis provides insights into how pharmaceutical interventions alter microbial communities, potentially explaining drug efficacy or side effects. Additionally, the highly individualized nature of human microbiomes has prompted investigation into microbial fingerprints for forensic identification, where an individual's unique microbial signature can be traced from skin, oral, or gut samples [9]. Skin microbiome analysis, for instance, has demonstrated up to 100% classification accuracy for matching samples to specific individuals [9].

Agricultural, Environmental, and Industrial Applications

Beyond human health, targeted amplicon sequencing finds extensive applications in agricultural science, where it is used to study microbial interactions in the rhizosphere, the effects of agricultural practices on soil health, and plant-microbe relationships that influence crop productivity [1]. Understanding these microbial dynamics enables development of sustainable farming practices and microbiome-based solutions for plant health.

In environmental studies, these methods facilitate characterization of microbial communities in diverse habitats—from polluted ecosystems to extreme environments—providing insights into microbial adaptations and ecosystem functioning [1]. Industrial applications include monitoring bioremediation processes, optimizing wastewater treatment systems, and developing bioenergy solutions through identification of functional microbial strains [1]. In each context, the targeted approach provides a cost-effective means to survey microbial community structure and dynamics at scale.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 16S/ITS Amplicon Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation Buffers (e.g., RLT Plus with DTT) | Stabilize nucleic acids during sample storage | RNA stabilizers needed for RNA-based approaches [6] |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Kit) | Co-purification of DNA and RNA from same sample | Enables parallel DNA- and RNA-based analysis [6] |

| Barcoded PCR Primers | Amplification of target regions with sample indexes | Design affects taxonomic coverage and bias [3] [7] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification with minimal errors | Reduces PCR-derived sequence artifacts |

| PNA Clamps | Suppress host DNA amplification | Critical for low-biomass or host-contaminated samples [7] |

| Positive Control Standards (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard) | Monitor technical performance | Should mimic sample complexity [6] |

| Size Selection Beads | Cleanup and normalization of amplicon libraries | Affect size distribution and remove primer dimers |

| Sequencing Kits (Platform-specific) | Generate sequence data | Read length and error profiles vary by platform [5] [1] |

| (E,E)-8,10-dodecadienyl acetate | (E,E)-8,10-dodecadienyl acetate, CAS:53880-51-6, MF:C14H24O2, MW:224.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Hydroxy-7-acetoxy-8-methoxyflavone | 5-Hydroxy-7-acetoxy-8-methoxyflavone, MF:C18H14O6, MW:326.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Variations and Emerging Approaches

DNA-based vs. RNA-based Approaches

Most amplicon sequencing studies utilize DNA-based approaches, which reflect the total microbial community (including dormant cells and free DNA) present in a sample. However, RNA-based 16S rRNA sequencing is emerging as a complementary approach that specifically targets the active microbiota by reverse transcribing and sequencing rRNA molecules [6]. Since ribosomal RNA is more abundant than rRNA genes in metabolically active cells (e.g., E. coli contains ~25,000 ribosomes per cell), RNA-based approaches offer significantly higher sensitivity, particularly for low-biomass samples [6].

Comparative studies have demonstrated that RNA-based analysis typically reveals higher microbial diversity, with significant differences in alpha and beta diversity metrics compared to DNA-based approaches [6]. However, both methods have biases: DNA-based analysis is influenced by varying rRNA gene copy numbers (1-21 per genome), while RNA-based analysis is affected by differences in ribosome content per cell, which varies with growth rate and cell size [6]. A combined DNA-RNA approach provides the most comprehensive view of microbial communities, distinguishing between present and active members.

Technological Platforms and Their Applications

The evolution of sequencing technologies has dramatically expanded options for amplicon sequencing. Second-generation platforms (e.g., Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq) offer high accuracy and throughput for short reads (up to 600 bp), typically targeting one to three variable regions [3]. Third-generation platforms (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) enable full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing (~1500 bp), providing superior taxonomic resolution to the species and strain level [5].

Full-length sequencing reveals that many bacterial genomes contain multiple polymorphic copies of the 16S rRNA gene that vary slightly in sequence [5]. These intragenomic copy variants have traditionally been collapsed by short-read approaches but can be resolved with long-read technologies, potentially providing additional strain-level discrimination [5]. However, long-read technologies historically had higher error rates, though recent improvements in circular consensus sequencing (CCS) have substantially enhanced accuracy [5]. The choice of platform therefore represents a trade-off between read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost that must be optimized for each research question.

16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing represent powerful, targeted approaches for profiling microbial communities across diverse research contexts. The method's strength lies in its ability to provide comprehensive taxonomic characterization of complex samples in a cost-effective, high-throughput manner. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve—particularly with the emergence of accurate long-read platforms—the taxonomic resolution achievable through these approaches will continue to improve, potentially enabling reliable discrimination at the species and strain level.

Critical considerations for robust experimental design include appropriate selection of variable regions, careful sample handling to preserve community integrity, and implementation of bioinformatic pipelines that minimize technical artifacts while maximizing biological information. For certain applications, emerging variations such as RNA-based sequencing or full-length amplicon approaches may provide valuable complementary insights. As these methodologies become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, they will continue to drive discoveries in microbial ecology, host-microbe interactions, and the diverse roles of microorganisms in health, disease, and ecosystem functioning.

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a cornerstone of microbial ecology and serves as the universal genetic barcode for identifying and classifying Bacteria and Archaea [10]. This gene, approximately 1500 base pairs (bp) in length, contains a unique combination of evolutionarily conserved regions and nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that provide distinct taxonomic signatures [11] [10]. The conserved regions enable the design of universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers that can amplify this gene from virtually all prokaryotic organisms, while the variable regions contain sufficient sequence diversity to differentiate between microbial taxa at various phylogenetic levels, from domain to species [12].

The utility of the 16S rRNA gene extends beyond mere identification. Its application has revolutionized our understanding of microbial communities in diverse environments, from the human gut to extreme ecosystems. Through targeted amplicon sequencing, researchers can now characterize complex microbial populations without the limitations of culturing, revealing the tremendous diversity of microbial life that was previously undetectable using traditional microbiological methods [10]. The resulting data provide insights into microbial community structure, diversity, dynamics, and ecological functions, making 16S rRNA gene sequencing an indispensable tool in modern microbiology.

Molecular Foundations and Primer Design

Genetic Structure and Phylogenetic Significance

The 16S rRNA gene forms an integral component of the prokaryotic 30S ribosomal subunit, playing a critical role in protein synthesis by facilitating the initiation of mRNA translation and ensuring proper codon-anticodon pairing [13]. The gene's remarkable suitability as a phylogenetic marker stems from its functional constancy, universal distribution across prokaryotes, and appropriate evolutionary clock properties, with variable regions evolving at different rates that provide resolution at different taxonomic levels [13] [12].

The central pseudoknot structure, formed by nucleotides 17-19 pairing with nucleotides 916-918, represents a particularly conserved and functionally essential region of the 16S rRNA molecule [13]. This structural element is crucial for translational initiation and exhibits high susceptibility to point mutations, making it a critical consideration in primer design and functional studies [13]. The conservation of this and other functional domains ensures that the 16S rRNA gene maintains its essential cellular function while accumulating neutral mutations in non-critical regions that provide phylogenetic information.

Primer Design Strategies and Considerations

The design of PCR primers for 16S rRNA gene amplification represents a critical methodological step that directly influences experimental outcomes. Effective primer design must balance multiple competing objectives: maximizing coverage (the fraction of bacterial 16S sequences successfully targeted), optimizing efficiency (the ability to amplify target sequences specifically and robustly), and minimizing primer matching-bias (differential amplification of certain taxa over others) [14].

Computational approaches like the Multi-Objective Primer Optimization for 16S experiments (mopo16S) algorithm have been developed to systematically evaluate and optimize primer sets based on these criteria [14]. These methods employ multi-objective optimization that simultaneously considers thermodynamic properties (melting temperature, GC-content), structural characteristics (3'-end stability, secondary structure formation), and taxonomic coverage against comprehensive 16S rRNA reference databases [14]. The development of degenerate primers—mixtures of oligonucleotides with variations at specific positions—has further enhanced the ability to target diverse microbial taxa, though these introduce challenges in reproducible synthesis and potential amplification biases [14].

Table 1: Key Considerations for 16S rRNA Primer Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 52°C or higher | Primer binding efficiency; specificity of amplification |

| GC Content | 40-70% | Specificity and stability of primer-template binding |

| 3'-End Stability | Avoid poly-A/T tracts | Prevention of non-specific amplification |

| Primer Length | 18-25 bp | Balance between specificity and coverage |

| Degenerate Positions | Minimize when possible | Reduced synthesis reproducibility and potential bias |

Recent advances in primer design have addressed previously overlooked mismatches at critical positions. For example, the common universal primers Bac8f and UN1541r overlap variable sites at positions 19 and 1527, which can introduce mutations during amplification, particularly problematic at position 19 due to its involvement in the central pseudoknot [13]. New primer sets such as Bac1f and UN1542r have been designed to avoid these mismatch sites, improving amplification accuracy [13].

Experimental Approaches and Sequencing Platforms

Short-Read versus Long-Read Sequencing

The selection of sequencing platform represents a fundamental methodological choice that governs the scope and resolution of 16S rRNA gene analysis. Short-read sequencing platforms, particularly Illumina systems, have traditionally dominated 16S rRNA sequencing due to their high throughput, low per-base cost, and well-established analytical pipelines [11] [10]. However, these platforms are limited by read length constraints, typically targeting only 1-3 variable regions (such as V3-V4 or V4-V5) in a single experiment, which restricts taxonomic resolution, often to the genus level [11] [15].

In contrast, long-read sequencing technologies offered by Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) enable full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing (~1500 bp) or even entire ribosomal RNA operon (RRN) sequencing (~4500 bp), which spans the 16S-ITS-23S genomic region [16] [15]. This comprehensive approach captures all variable regions and provides substantially improved phylogenetic resolution, frequently enabling species-level and sometimes strain-level discrimination [15]. The advancement of these platforms, particularly with ONT's Q20+ chemistry and PacBio's HiFi sequencing, has addressed earlier limitations in accuracy, making long-read approaches increasingly viable for high-resolution microbial profiling [15].

Table 2: Comparison of 16S rRNA Sequencing Approaches

| Platform | Read Length | Target Region | Taxonomic Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq | 2×300 bp | Single or dual variable regions (e.g., V3-V4) | Genus-level | High-throughput community profiling |

| xGen Amplicon Panel | Multiple discontinuous regions | All 9 variable regions (separate amplicons) | Species-level with multi-region approach | Species-level identification from short reads |

| PacBio HiFi | Full-length 16S (~1500 bp) | Entire 16S rRNA gene | Species-level | High-accuracy full-length sequencing |

| Oxford Nanopore | Full-length 16S or RRN | Complete 16S or 16S-ITS-23S operon | Species to strain-level | Real-time sequencing; portable analysis |

Multi-Variable Region Sequencing with Short-Read Platforms

Innovative approaches have been developed to enhance taxonomic resolution while maintaining the benefits of short-read sequencing. The xGen 16S Amplicon Panel v2 utilizes multiple primer pairs to generate amplicons covering all nine variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, which are sequenced concurrently on Illumina platforms [11]. When processed through specialized bioinformatics pipelines like Swift Normalase Amplicon Panels APP for Python 3 (SNAPP-py3), this method achieves species-level resolution typically associated with long-read approaches while leveraging the cost-effectiveness and throughput of Illumina sequencing [11].

This multi-region approach addresses the fundamental limitation of single-region sequencing by capturing complementary taxonomic information from different variable regions, as each region possesses different discriminatory power for various bacterial taxa [11]. The method has demonstrated high reproducibility in technical replicates and accurate species-level identification in mock communities, with observed relative abundances closely matching theoretical expectations [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

The initial steps of sample collection and nucleic acid extraction critically influence downstream results in 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Collection methods must be tailored to the sample type—whether stool, rectal swabs, tissue, or environmental samples—as different collection approaches can yield substantially different microbial profiles even when sampling the same source [11] [17]. For example, concurrent stool and rectal swab samples from the same infants show significant differences in microbial composition, highlighting the importance of consistent methodology throughout a study [11].

DNA extraction should be optimized for the specific sample type to maximize yield while preserving accurate community representation. Key considerations include cell lysis efficiency across different bacterial taxa (Gram-positive versus Gram-negative), inhibition removal, and minimization of DNA shearing. The inclusion of mock community controls containing known quantities of specific bacterial species is essential for evaluating extraction efficiency and identifying technical biases introduced during this process [11] [17].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Short-Red Multi-Variable Region Protocol (xGen 16S Amplicon Panel)

The xGen 16S Amplicon Panel v2 enables comprehensive profiling of all nine variable regions through the following workflow [11]:

DNA Quality Assessment: Verify DNA quantity and quality using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) and ensure integrity through electrophoretic analysis.

Multiplex PCR Amplification: Utilize the panel's primer mixture to simultaneously amplify all variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene in a single, multiplexed reaction.

Library Construction: Process amplicons through indexing PCR to add sample-specific barcodes and sequencing adapters compatible with Illumina platforms.

Library Normalization and Pooling: Quantify individual libraries, normalize to equimolar concentrations, and combine into a single sequencing pool.

Sequencing: Load the pooled library onto an Illumina MiSeq or similar instrument using appropriate read length (e.g., 2×300 bp) to ensure sufficient overlap for paired-end assembly.

This protocol is particularly valuable when species-level resolution is required but access to long-read sequencing is limited, providing a compromise between information content and platform accessibility [11].

Full-Length 16S and RRN Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore Protocol)

The Oxford Nanopore Microbial Amplicon Barcoding Kit (SQK-MAB114.24) provides a workflow for full-length 16S or ITS sequencing [16]:

PCR Amplification: Amplify the full-length 16S rRNA gene using inclusive primers designed for broad taxonomic coverage. Reaction conditions: 10 ng gDNA template, LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix, 16S-specific primers, with thermal cycling parameters according to manufacturer specifications.

Amplicon Barcoding: Attach unique barcodes to individual amplicon samples using a 15-minute barcoding reaction, enabling multiplexing of up to 24 samples.

Pooling and Clean-up: Combine barcoded samples and purify using bead-based clean-up to remove primers, dimers, and other contaminants.

Adapter Ligation: Rapidly attach sequencing adapters (5 minutes) without additional PCR amplification, preserving the integrity of full-length amplicons.

Priming and Loading: Prepare the flow cell with priming buffer and load the adapted library for sequencing.

Sequencing and Real-time Analysis: Initiate sequencing runs through MinKNOW software, with optional real-time analysis through EPI2ME 16S workflow for immediate taxonomic classification [16].

This fragmentation-free workflow preserves full-length amplicons, enabling complete coverage of the 16S rRNA gene and maximizing phylogenetic resolution [16].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipelines

The analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing data requires specialized bioinformatics tools to transform raw sequence data into biological insights. Two established platforms, QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology) and mothur, provide comprehensive pipelines for processing 16S rRNA amplicon data [18]. These toolsets incorporate quality filtering, chimera detection, sequence clustering, taxonomic classification, and diversity analysis in reproducible workflows.

For users seeking more accessible interfaces, the Galaxy mothur Toolset (GmT) provides a user-friendly web interface for the complete suite of mothur tools, enabling researchers without command-line expertise to perform sophisticated analyses [19]. The standard GmT workflow includes [19]:

- Read Processing: Pair-end read merging (make.contigs) and quality trimming (trim.seqs)

- Alignment and Filtering: Alignment to reference databases (align.seqs) and sequence screening (screen.seqs)

- Chimera Removal: Identification and removal of chimeric sequences (chimera.uchime)

- Taxonomic Classification: Bayesian classification against reference databases (classify.seqs)

- OTU Clustering: Distance calculation (dist.seqs) and OTU clustering at 97% similarity (cluster)

- Diversity Analysis: α- and β-diversity calculations and visualization

The emergence of long-read sequencing has necessitated the development of specialized classification approaches for full-length 16S and RRN data. The Minimap2 classifier in combination with comprehensive databases like GROND has demonstrated superior performance for species-level classification of RRN sequencing data, outperforming traditional OTU-clustering methods [15].

16S rRNA Gene Analysis Workflow: From Sample to Interpretation

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 16S rRNA Gene Analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Tool | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Kits | xGen 16S Amplicon Panel v2 | Amplification of all 9 variable regions for Illumina sequencing |

| Microbial Amplicon Barcoding Kit (ONT) | Full-length 16S or ITS sequencing on Nanopore platforms | |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Standards | Mock community controls for quality validation | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME 2 | Comprehensive pipeline for 16S rRNA data analysis |

| mothur | Open-source platform for microbial community analysis | |

| Galaxy mothur Toolset (GmT) | Web-based interface for mothur tools | |

| Minimap2 | Alignment tool for long-read 16S and RRN data | |

| Reference Databases | SILVA | Curated database of aligned ribosomal RNA sequences |

| GreenGenes | 16S rRNA gene database and taxonomy | |

| GROND | Database for ribosomal RNA operon analysis | |

| RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) | Annotated database of rRNA sequences |

Applications and Best Practices

Applications in Microbial Research

The applications of 16S rRNA gene sequencing span diverse research areas, from clinical microbiology to environmental science. In human microbiome studies, this approach has revealed microbial dysbiosis associated with chronic conditions such as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), where decreased microbial diversity and altered abundance of specific taxa correlate with disease severity and clinical outcomes [12]. In agricultural research, 16S rRNA profiling has characterized poultry gastrointestinal microbiota and its relationship to host health, nutrition, and growth performance [17].

The technology continues to evolve with emerging applications in forensic microbiology, bioremediation monitoring, food safety, and built environment analysis. The expanding utilization of this method across disciplines underscores its fundamental importance in understanding microbial systems in virtually every environment on Earth.

Standardization and Reproducibility Considerations

The proliferation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing applications has revealed significant challenges in methodological standardization and reproducibility. Variations in DNA extraction protocols, primer selection, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatic analyses can introduce substantial biases, affecting community structure representation and leading to over- or under-estimation of specific taxa [17]. These methodological differences make cross-study comparisons problematic and highlight the need for standardized protocols within research communities.

Best practices to enhance reproducibility include [11] [17]:

Incorporation of Mock Controls: Routine use of defined microbial communities to quantify technical variability and accuracy.

Detailed Methodological Reporting: Comprehensive documentation of DNA extraction methods, primer sequences, PCR conditions, and bioinformatic parameters.

Platform Validation: Assessment of multiple variable regions or full-length sequencing when possible to overcome region-specific biases.

Data Sharing and Public Archiving: Deposition of raw sequence data and associated metadata in public repositories to enable reanalysis and comparison.

Database Consistency: Use of consistent, curated reference databases with version control to ensure comparable taxonomic classifications.

The development of field-specific guidelines for 16S rRNA gene sequencing, encompassing sample collection through data deposition, represents an ongoing effort to improve reliability and comparability across microbial community studies [17].

The 16S rRNA gene remains an indispensable tool for microbial identification and community analysis, continuing to provide fundamental insights into the diversity, ecology, and function of prokaryotic communities across diverse environments. Advances in sequencing technologies, particularly the emergence of long-read platforms and multi-region amplification approaches, have enhanced the resolution and accuracy of 16S rRNA-based studies, enabling species-level discrimination that was previously challenging with short-read methods.

As the field continues to evolve, the integration of 16S rRNA gene sequencing with other 'omics approaches—including metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics—will provide more comprehensive understanding of microbial community structure and function. Similarly, the development of standardized protocols and reference materials will strengthen the reproducibility and comparability of findings across studies. Through these continued methodological refinements and applications, 16S rRNA gene sequencing will maintain its central role in advancing our understanding of the microbial world that shapes human health, ecosystem function, and global biogeochemical cycles.

The Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene cluster has been established as the official primary DNA barcode for fungi, providing a powerful tool for mycologists, ecologists, and drug development professionals engaged in microbial community analysis [10] [20]. This non-coding region, characterized by significant sequence variability and flanked by highly conserved genes, enables precise taxonomic classification and has become the cornerstone of modern fungal diversity studies using amplicon sequencing technologies [21] [22].

The adoption of the ITS region as the universal fungal barcode stems from several key advantages: its multicopy nature within the fungal genome, which facilitates amplification from minute quantities of DNA; the presence of conserved regions that allow for the design of broad-range primers; and sufficient sequence variation to discriminate between closely related species across the fungal kingdom [10] [23] [22]. Compared to other genetic markers, the ITS region offers an optimal balance of conservation and variability, making it particularly suitable for phylogenetic studies and environmental sampling where unknown fungal diversity is expected [24] [1].

The ITS Region: Structure and Rationale for Fungal Barcoding

Molecular Architecture

The ITS region is located within the rRNA gene cluster and consists of two variable spacers:

- ITS1: Located between the 18S (small subunit) and 5.8S rRNA genes, typically ranging from 150-400 bp in length [24]

- ITS2: Situated between the 5.8S and 28S (large subunit) rRNA genes, with a similar length range to ITS1 [21]

- Flanking regions: The ITS region is bounded by the 18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNA genes, which contain conserved sequences ideal for primer binding [21] [1]

The complete ITS region (including the 5.8S gene) typically spans 500-750 base pairs, though this length can vary considerably across fungal taxa [21]. This variability in length and sequence composition provides the phylogenetic signal necessary for distinguishing between species.

Comparative Advantages Over Alternative Markers

While other genetic regions such as RPB1, RPB2, β-tubulin, and TEF1α (the secondary fungal barcode) may offer superior discrimination for specific taxonomic groups, the ITS region remains the most comprehensively utilized marker for fungal identification [24]. Key comparative advantages include:

- Amplification success: Higher amplification rates across diverse fungal taxa compared to protein-coding genes [24]

- Database coverage: Substantially more reference sequences in public databases than any other fungal marker [24]

- Taxonomic resolution: Generally provides species-level identification for most fungi, though resolution varies among genera [24] [20]

The ITS region's limitations are most apparent in certain ubiquitous genera such as Aspergillus and Penicillium, where interspecific variation may be insufficient for reliable discrimination [24] [20]. In such cases, supplemental markers may be required for definitive identification.

Experimental Performance and Comparative Analysis

Assessment of ITS1 versus ITS2 Subregions

The length of the complete ITS region (500-700 bp) often exceeds the optimal read length of widely used Illumina platforms, necessitating targeted sequencing of either the ITS1 or ITS2 subregion [24]. Research using defined mock communities has yielded important insights into the comparative performance of these subregions:

Table 1: Performance comparison of ITS1 and ITS2 subregions based on defined mock community analysis

| Parameter | ITS1 | ITS2 | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Lower | Slightly better | Illumina sequencing of 37 defined mock communities [24] |

| Recall | Comparable | Comparable | Illumina sequencing of 37 defined mock communities [24] |

| Amplicon Length | 150-400 bp | 150-400 bp | Varies by taxonomic group [24] |

| Primer Universality | Fewer universal primer sites | More universal primer sites | Affects amplification success across diverse taxa [24] |

| Diversity Estimation | May overestimate diversity | More conservative estimates | Due to higher variability in ITS1 [24] |

| Database Representation | Variable by taxonomic group | Variable by taxonomic group | Affects classification accuracy [24] |

The choice between ITS1 and ITS2 involves trade-offs that must be considered in experimental design. While ITS2 typically provides slightly better precision with comparable recall, the optimal subregion may depend on the specific fungal taxa being investigated and the reference databases available for classification [24].

Bioinformatics and Database Considerations

Classification accuracy in ITS sequencing depends critically on bioinformatics tools and reference database selection:

Table 2: Impact of bioinformatics methods and databases on classification accuracy

| Factor | Options | Performance Considerations | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Algorithm | BLAST | Better performance but may require expert curation | Mock community evaluation [24] |

| mothur (Bayesian) | Better performance in automated workflow | Mock community evaluation [24] | |

| Reference Database | UNITE | Widely adopted, species hypotheses | Variable performance depending on taxa [24] |

| BCCM/IHEM | Specialized collection, better for medical fungi | Outperformed UNITE in mock community study [24] | |

| NCBI RTL/ISHAM | Curated databases for specific applications | Important for pathogenic fungi [24] | |

| Taxonomic Level | Species level | Challenging for some genera (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium) | Lower precision compared to genus level [24] |

| Genus level | Generally reliable classification | Good precision and recall [24] | |

| Intermediate levels | May present adequate alternatives | Species complex or section level [24] |

Recent research demonstrates that classification performance varies considerably depending on all considered variables, with 56-100% of species correctly assigned across different experimental setups [24]. The reference database employed has a marked effect, with specialized databases such as BCCM/IHEM sometimes outperforming more general databases like UNITE, likely due to differences in sequence curation and taxonomic coverage relevant to specific research questions [24].

Wet Laboratory Protocols

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Environmental Sample Collection:

- Air samples: Collect using cyclonic samplers (e.g., NIOSH BC251) at 2-15 L/min onto 0.8 μm mixed cellulose ester filters [22]

- Dust samples: Composite collections from vacuum bags or sieved dust (300-mesh) from carpets and floors [22]

- Clinical specimens: Swabs, tissue biopsies, or bodily fluids collected in sterile containers

- Soil/water: Collection of representative samples using sterile corers or filtration systems

DNA Extraction Protocol:

- Mechanical disruption: Process samples with glass beads (212-300 μm) in a bead beater for 15-30 seconds at high speed [22]

- Lysis: Add commercial lysis buffer (e.g., High Pure PCR Template Kit) and incubate according to manufacturer specifications

- DNA purification: Bind DNA to silica columns, wash with appropriate buffers, and elute in 50-100 μL elution buffer [22]

- Quality assessment: Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods and verify quality via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ≥1.8)

PCR Amplification and Library Preparation

Primer Selection:

- ITS1-F/ITS2: For ITS1 region amplification (~300 bp) [25]

- ITS3/ITS4: For ITS2 region amplification (~400 bp) [25]

- Full-ITS primers: For long-read sequencing platforms (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore)

Amplification Protocol:

- Reaction setup:

- 2X PCR Master Mix: 25 μL

- Forward primer (10 μM): 2.5 μL

- Reverse primer (10 μM): 2.5 μL

- DNA template: 2-10 ng

- Nuclease-free water to 50 μL

Thermal cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 3-5 minutes

- 25-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 50-55°C for 30-45 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 60-90 seconds

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

Library preparation:

- Clean amplified products using magnetic beads

- Attach platform-specific adapters and barcodes

- Validate library quality using bioanalyzer or tape station

Bioinformatics Analysis Workflow

Data Processing and Taxonomic Classification

Quality Control and Denoising:

- Raw read processing:

- Demultiplex samples based on barcodes

- Trim primers and adapters using tools like cutadapt [25]

- Quality filtering based on Q-scores (typically Q≥20)

Denoising approaches:

- DADA2: For Illumina data to resolve amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [25]

- Deblur: For single-end Illumina data with quality trimming

- UNOISE: For denoising and chimera removal

Sequence clustering:

Taxonomic Classification:

- Reference-based assignment:

- Align sequences to curated databases (UNITE, BCCM/IHEM) using BLAST, Naive Bayes, or alignment tools [24]

- Consider both percent identity and query coverage thresholds

- Confidence assessment:

- Apply bootstrap thresholds (typically ≥80%) for reliable assignments

- Consider taxonomic hierarchies from species to phylum level

Diversity and Community Analysis

Alpha Diversity (within-sample diversity):

- Richness estimators: Chao1, ACE, observed OTUs/ASVs

- Diversity indices: Shannon, Simpson, Inverse Simpson

- Evenness: Pielou's evenness, Simpson's evenness

Beta Diversity (between-sample diversity):

- Distance metrics: Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, Unweighted/Weighted UniFrac

- Ordination methods: PCoA, NMDS, CCA

- Statistical testing: PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, Mantel test

Differential Abundance Analysis:

- Statistical tests: DESeq2, edgeR, LEfSe, METASTATS

- Multivariate methods: RDA, CCA for environmental correlations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for fungal ITS analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | High Pure PCR Template Kit (Roche) | Efficient DNA extraction from complex samples | Optimal for air and dust samples [22] |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction from soil and environmental samples | Effective for difficult-to-lyse fungi | |

| PCR Amplification | ITS1-F/ITS2 primers | Amplification of ITS1 subregion | Fragment size ~300 bp [25] |

| ITS3/ITS4 primers | Amplification of ITS2 subregion | Fragment size ~400 bp [25] | |

| 5.8S-Fun/ITS4-Fun primers | Full ITS amplification for specific applications | Amplicon range: 267-511 bp [25] | |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep | Library construction for Illumina platforms | Integrated workflow for amplicon sequencing [10] |

| SQK-16S024 kit (Oxford Nanopore) | Full-length ITS sequencing | Enables long-read ITS analysis [15] | |

| Quality Control | Agilent Bioanalyzer | Library quality assessment | Determines fragment size distribution |

| Qubit Fluorometer | DNA quantification | More accurate than spectrophotometry for low concentrations | |

| Bioinformatics | QIIME2 platform | End-to-end analysis of ITS data | Extensive plugin ecosystem [25] |

| mothur pipeline | Alternative analysis workflow | Well-established for microbial communities [24] | |

| UNITE database | Primary reference for taxonomic assignment | Species hypotheses approach [24] [25] | |

| BCCM/IHEM database | Specialized database for medical fungi | Enhanced performance for clinical isolates [24] | |

| N-Desmethyl Rosiglitazone | N-Desmethyl Rosiglitazone, CAS:257892-31-2, MF:C17H17N3O3S, MW:343.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Sec-butyl-3-methoxypyrazine | 2-sec-Butyl-3-methoxypyrazine | High-Purity Reference Standard | 2-sec-Butyl-3-methoxypyrazine for flavor & olfaction research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Environmental Mycology

ITS-based metabarcoding has revolutionized environmental mycology by providing culture-independent characterization of fungal communities:

- Indoor mycology: Identification of diverse Ascomycota and Basidiomycota communities in homes of asthmatic children, revealing previously overlooked taxa with potential health implications [22]

- Agricultural systems: Analysis of rhizosphere fungi and their responses to agricultural practices, with potential applications in crop protection and soil health assessment

- Biogeographic studies: Investigation of fungal distribution patterns across environmental gradients and ecosystem types

Clinical and Pharmaceutical Applications

The precision of ITS sequencing enables critical applications in clinical diagnostics and drug discovery:

- Clinical mycology: Species-level identification of pathogens in otomycosis cases, revealing Aspergillus as the dominant pathogen and Malassezia as prevalent in healthy ears [21]

- Drug discovery: Identification of novel fungal species from unique environments as potential sources of bioactive compounds

- Pharmaceutical quality control: Detection of fungal contaminants in manufacturing environments and finished products

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Despite its utility, researchers must acknowledge several methodological considerations:

- Intragenomic variation: Approximately 65% of multi-copy fungal genomes contain ITS sequence variation, which can affect diversity estimates and taxonomic assignments [23]

- Database inaccuracies: Up to 20% of public repository sequences may be incorrectly annotated, emphasizing the need for curated databases [24]

- Technical biases: DNA extraction efficiency, primer selection, and PCR conditions can all influence community representation [24] [22]

The ITS region remains the gold standard for fungal identification and diversity assessment, offering unparalleled taxonomic resolution across most fungal groups. While challenges persist in species-level discrimination for certain genera and in managing technical artifacts, ongoing refinements in sequencing technologies, reference databases, and bioinformatics pipelines continue to enhance its utility. For researchers and drug development professionals, ITS-based approaches provide a powerful framework for exploring fungal communities in diverse contexts, from environmental ecosystems to clinical settings, with important implications for ecological understanding, public health, and biotechnological innovation.

Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Culture-Free Microbial Profiling

Culture-free microbial profiling, primarily through 16S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing, has revolutionized microbial community analysis by enabling comprehensive biodiversity assessment beyond the constraints of cultivability. These methods provide unprecedented insights into microbial community composition, dynamics, and functional potential across diverse environments from human health to industrial applications. However, inherent technical and biological limitations—including primer bias, variable gene copy numbers, inability to distinguish viable from non-viable cells, and analytical pipeline dependencies—significantly impact data interpretation. This application note delineates the advantages and limitations of culture-free profiling methodologies within 16S rRNA and ITS research frameworks, providing structured experimental protocols, quantitative performance comparisons, and standardized workflows to enhance research reproducibility and analytical accuracy for scientists and drug development professionals.

Traditional microbial characterization relying on laboratory cultivation has historically limited our understanding of microbial diversity, as an estimated 99% of microorganisms cannot be cultured under standard laboratory conditions [26]. Culture-free microbial profiling, utilizing targeted amplicon sequencing of phylogenetic marker genes such as the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene for bacteria and archaea and the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region for fungi, has fundamentally transformed microbial ecology and diagnostics. This approach enables the precise identification and relative quantification of microbial taxa directly from complex samples without cultivation bias [27] [28].

The power of these methods lies in their ability to provide high-resolution community analysis from diverse sample types, including human tissues, environmental samples, and industrial products. By targeting conserved yet variable genetic regions, researchers can characterize microbiomes at various taxonomic levels, exploring community shifts in response to disease, environmental changes, or therapeutic interventions [29] [28]. Despite their transformative impact, the techniques carry inherent limitations that must be acknowledged and mitigated to ensure biologically accurate interpretations. This application note details the balanced landscape of culture-free microbial profiling, providing a framework for its rigorous application in research and drug development.

Advantages of Culture-Free Microbial Profiling

Comprehensive Community Analysis

Unlike culture-dependent methods that selectively isolate microorganisms based on their growth requirements, culture-free profiling captures the entire microbial community present in a sample.

- Identification of Unculturable Taxa: Advanced Microbial Profiling (AMP) reveals organisms that are difficult or impossible to culture in the lab, providing a more complete picture of microbial diversity [26].

- Detection of Injured and Viable-but-Non-Culturable (VBNC) Cells: The method identifies both healthy and metabolically compromised microbial cells that would otherwise escape detection through traditional culturing [26].

- High-Throughput Capacity: The technology can analyze dozens of samples simultaneously, generating thousands of microbial marker sequences per sample in a single run, enabling robust statistical analysis and population dynamics studies [26].

Enhanced Sensitivity and Resolution

The sensitivity of culture-free methods significantly surpasses traditional approaches, enabling detection of low-abundance taxa and fine-scale differentiation between closely related organisms.

- Superior Sensitivity: RNA-based 16S rRNA sequencing demonstrates at least a 10-fold higher sensitivity compared to DNA-based approaches, enabling detection of rare taxa in low-biomass samples like the uterine microbiome [6].

- Strain-Level Differentiation: Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) methods like DADA2 offer single-nucleotide resolution, providing finer taxonomic precision than traditional Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering and enabling tracking of specific bacterial strains within communities [28].

Diagnostic and Predictive Capabilities

Culture-free profiling has demonstrated significant utility in clinical diagnostics by detecting pathogens that evade traditional methods and providing predictive insights into microbial community functions.

- Clinical Pathogen Detection: The MYcrobiota platform confirmed bacterial DNA in 37/37 culture-positive clinical samples and detected potentially relevant bacterial taxa in 2/10 culture-negative samples, demonstrating 95% sensitivity and specificity compared to culture [29].

- Functional Prediction: Tools like Tax4Fun predict functional profiles from 16S rRNA data, linking phylogenetic information to potential metabolic capabilities within microbial communities [30].

- Process Monitoring: In anaerobic digestion, linking microbial community dynamics to operational parameters allows for better process control and stability prediction [30].

Table 1: Quantitative Advantages of Culture-Free vs. Culture-Based Methods

| Parameter | Culture-Free Profiling | Traditional Culturing |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Threshold | 0.01% relative abundance [28] | ≥1% (culture-dependent) |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Species/Strain level (ASV) [28] | Species level (MALDI-TOF) [29] |

| Process Time | 1-3 days [28] | 2-5 days [29] |

| Throughput | Dozens of samples simultaneously [26] | Limited by cultivation space |

| Unculturable Detection | Yes [26] | No |

| Sensitivity in Low Biomass | 10-fold higher for RNA-based [6] | Limited |

Inherent Limitations and Biases

Technical and Methodological Biases

Multiple technical steps in culture-free profiling introduce distortions that may not accurately reflect the original microbial community composition.

- Primer Selection Bias: The choice of primer pairs and amplified variable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4-V5) significantly influences which taxa are detected and their relative abundances [31] [28]. Different hypervariable regions exhibit varying degrees of conservation and discrimination power.

- DNA Extraction Efficiency: Lysis efficiency varies across microbial taxa due to differences in cell wall structure, potentially underrepresenting difficult-to-lyse organisms like Gram-positive bacteria [6].

- PCR Amplification Bias: During amplification, template-specific variations in PCR efficiencies (PCR competition) and formation of chimeric sequences distort abundance measurements, particularly in polymicrobial samples [29].

- Gene Copy Number Variation: The 16S rRNA gene copy number varies significantly (1-21 copies per genome) across bacterial taxa, leading to overestimation of species with high copy numbers and underestimation of those with low copy numbers when using DNA-based approaches [6].

Biological Limitations

Fundamental biological considerations limit the interpretation of data generated from culture-free profiling approaches.

- Viability Assessment: DNA-based analysis cannot distinguish between live bacteria, dead cells, and free bacterial DNA, potentially leading to false positive results in viability-dependent contexts [29] [6].

- Ribosomal Content Variability: RNA-based approaches are biased by the number of ribosomes per cell, which varies with growth rate, cell size, and metabolic activity, complicating abundance quantification [6].

- Host DNA Contamination: In low-microbial-biomass samples (e.g., BALF, tissue biopsies), host DNA can comprise over 99.99% of total DNA, drastically reducing microbial sequencing depth unless depletion methods are employed [32].

Analytical and Bioinformatics Challenges

The interpretation of sequencing data is heavily dependent on bioinformatics pipelines, which can yield dramatically different biological conclusions.

- Pipeline-Dependent Results: Common analysis tools (QIIME, Mothur, QIIME2) produce significantly different taxonomic compositions from the same environmental dataset, with abundant taxa potentially going undetected depending on the pipeline selected [33].

- Contamination Sensitivity: The techniques are highly susceptible to contamination from laboratory reagents and environments, particularly problematic for low-biomass samples where contaminant DNA can exceed target DNA [29] [32].

- Database Limitations: Incomplete reference databases lead to limited read assignment and substantial gaps in data interpretation, particularly for novel or understudied lineages [30].

Table 2: Systematic Biases in Culture-Free Profiling Methodologies

| Bias Type | Impact on Results | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Selection | Variable detection of taxa; abundance distortion [31] | Use well-validated primer sets; multiple variable regions |

| Gene Copy Number | Over/under-estimation of taxa abundance [6] | Apply copy number correction algorithms |

| Viability Blindness | Detection of non-viable cells and free DNA [6] | Incorporate propidium monoazide (PMA) treatment |

| Host DNA Contamination | Reduced microbial sequencing depth [32] | Implement host depletion methods (saponin, nucleases) |

| PCR Artifacts | Chimera formation; abundance inaccuracies [29] | Use micelle PCR; internal calibrators; validation |

| Bioinformatic Pipeline | Dramatically different community profiles [33] | Standardize pipeline; mock community validation |

Experimental Protocols

DNA- and RNA-Based 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

This protocol outlines a simultaneous DNA and RNA extraction method followed by 16S rRNA (gene) amplicon sequencing to differentiate between total and active microbial communities [30] [6].

Sample Preparation and Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Sample Preservation: Immediately freeze samples at -80°C or in liquid nitrogen. For RNA preservation, add 25% glycerol to samples before freezing [32].

- Simultaneous DNA/RNA Extraction: Use the RNA PowerSoil Total RNA Isolation Kit with the RNA PowerSoil DNA Elution Accessory Kit (MoBio Laboratories) for co-extraction [30].

- DNase Treatment: Treat RNA extracts with DNase I Kit for Purified RNA in Solution to remove residual DNA. Validate DNA removal via PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene followed by agarose gel electrophoresis [30].

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert RNA to cDNA using the qScriber cDNA Synthesis Kit [30].

- Quality Control: Assess nucleic acid quality and concentration using Nanodrop spectrophotometry and fluorometric methods (e.g., QuantiFluor RNA/DNA Systems) [6].

16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Sequencing:

- Primer Selection: Target the V3-V4 hypervariable region using primers 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 785R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC) for bacterial communities [30].

- PCR Amplification: Perform amplification using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase with the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 25-30 cycles of 95°C for 40 sec, 53°C for 40 sec, 72°C for 60 sec; final elongation at 72°C for 7 min [31].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Purify amplicons using Agencourt AMPure XP beads, prepare Illumina-compatible libraries using the Ovation Rapid DR Multiplex System, and sequence on Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq platforms with 200-250bp paired-end reads [30] [28].

Host DNA Depletion for Low-Biomass Samples

For samples with high host-to-microbe ratios (e.g., BALF, tissue biopsies), implement host DNA depletion to increase microbial sequencing depth [32].

Pre-extraction Methods (Select one approach):

- Saponin Lysis with Nuclease Digestion (S_ase):

- Treat sample with 0.025% saponin to lyse mammalian cells

- Follow with nuclease digestion to degrade released host DNA

- Centrifuge to pellet intact microbial cells

- Proceed with DNA extraction from pellet [32]

- Filter-based Method with Nuclease Digestion (F_ase):

- Filter sample through 10μm filter to separate microbial from host cells

- Treat filtrate with nuclease to digest cell-free DNA

- Collect microbial cells via centrifugation

- Proceed with DNA extraction [32]

Quality Control:

- Quantify host DNA depletion efficiency via qPCR targeting human-specific genes (e.g., β-actin)

- Monitor bacterial DNA retention using 16S rRNA gene qPCR [32]

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for DNA- and RNA-based microbial community analysis, including host depletion for low-biomass samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Culture-Free Microbial Profiling

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| PowerSoil DNA/RNA Isolation Kit (MoBio) | Simultaneous nucleic acid co-extraction | Maintains ratio between DNA and RNA communities; reduces extraction bias [30] |

| AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit (Qiagen) | Parallel nucleic acid purification | Optimal for low-biomass samples like uterine cytobrushes [6] |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | Host DNA depletion (post-extraction) | Selective methylation-based depletion; less effective for respiratory samples [32] |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit (Zymo) | Host DNA depletion (pre-extraction) | High efficiency host removal; reduces human DNA to 0.9‱ of original [32] |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) | 16S rRNA gene amplification | Reduces PCR errors; maintains sequence fidelity [31] |

| PNA Clamps/Blocking Oligonucleotides | Inhibition of host gene amplification | Suppresses mitochondrial 12S rRNA amplification in eukaryotic samples [6] |

| Agencourt AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) | PCR purification and size selection | Removes primer dimers; selects appropriate amplicon size [30] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Mock community control | Validates sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy [6] |

| 7-Hydroxycoumarin-4-acetic acid | 7-Hydroxycoumarin-4-acetic Acid | High Purity Reagent | 7-Hydroxycoumarin-4-acetic acid is a key fluorescent probe & substrate for enzyme assays. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Fluoresceinamine Maleic Acid Monoamide | Fluoresceinamine Maleic Acid Monoamide | RUO | Fluoresceinamine Maleic Acid Monoamide is a key fluorescent probe for bioconjugation & protein labeling. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Culture-free microbial profiling represents a powerful paradigm shift in microbial community analysis, offering unprecedented depth and breadth in taxonomic characterization that far surpasses traditional culture-based methods. The techniques provide robust tools for clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and industrial process control by detecting previously inaccessible microorganisms and revealing complex community dynamics. However, the inherent methodological limitations—spanning technical biases, biological constraints, and analytical challenges—necessitate careful experimental design and cautious data interpretation.

Strategic implementation requires selecting appropriate protocols based on sample type and research questions, incorporating both DNA- and RNA-based approaches to distinguish between total and active communities, applying rigorous controls for contamination and viability assessment, and standardizing bioinformatics pipelines to ensure reproducible results. As these technologies continue to evolve with improved host depletion methods, single-nucleotide resolution, and more comprehensive reference databases, culture-free profiling will increasingly bridge the gap between microbial community structure and function, offering enhanced predictive capabilities for research and drug development professionals.

The study of microbial communities has been revolutionized by the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, moving beyond culture-dependent methods that could only access a small fraction of microbial diversity [34] [35]. Three principal methodologies have emerged as cornerstones of modern microbiome research: 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacteria and archaea, Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequencing for fungi, and shotgun metagenomic sequencing for comprehensive genomic analysis of all microorganisms [36] [37] [38]. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations, making the choice of methodology a critical initial decision that shapes all subsequent experimental processes, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

This framework provides a structured approach for researchers to select the most appropriate sequencing method based on their specific research questions, sample types, and resource constraints. By comparing these technologies across multiple dimensions—including taxonomic resolution, functional capability, cost, and analytical requirements—we aim to equip scientists with the tools needed to design robust and informative microbiome studies across diverse applications from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [36] [37].

Technology Comparison and Selection Framework

Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Technologies

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of microbial sequencing methodologies

| Factor | 16S rRNA Sequencing | ITS Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | ~$50 USD [39] | Similar to 16S [38] | Starting at ~$150+ (varies with depth) [39] |

| Target Organisms | Bacteria & Archaea [36] [39] | Fungi [38] [39] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Viruses [37] [39] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (sometimes species) [40] [39] | Species-level for fungi [38] | Species to strain-level [40] [37] [39] |

| Functional Profiling | No (only predicted via tools like PICRUSt) [36] [39] | Limited to taxonomic identification | Yes (direct assessment of genetic potential) [37] [39] |

| Experimental Bias | Medium-High (primer selection, amplification bias) [34] [39] | Medium-High (primer selection, amplification bias) | Lower (no targeted amplification) but analytical biases exist [37] [39] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner-Intermediate [36] [39] | Beginner-Intermediate | Intermediate-Advanced [37] [39] |

| Host DNA Contamination Sensitivity | Low [39] | Low | High (varies with sample type) [37] [39] |

| Reference Databases | Well-established (SILVA, Greengenes) [36] [35] | Specialized fungal databases | Growing but less curated (NCBI, GTDB) [37] [34] |

Decision Framework Workflow

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting the appropriate sequencing method based on key experimental considerations:

Sequencing Method Decision Workflow: This diagram provides a systematic approach for selecting the most appropriate sequencing method based on research goals, sample type, and available resources.

Application-Specific Recommendations

Different research scenarios demand distinct methodological approaches. For human gut microbiome studies where comprehensive functional insights are valuable, shotgun metagenomics is often preferred despite higher costs, as it provides strain-level resolution and direct functional assessment [34]. In environmental samples with potentially high fungal biomass or diverse microbial kingdoms, a multi-amplicon approach (combining 16S and ITS) may offer the most comprehensive taxonomic profile within budget constraints [38]. For longitudinal studies tracking specific bacterial populations over time, 16S rRNA sequencing provides a cost-effective solution, especially when targeting known bacterial groups [40] [36].

In clinical diagnostics where rapid pathogen identification is critical, targeted approaches often prevail. However, for unexplained infections or complex clinical presentations, shotgun metagenomics can provide unbiased detection of all potential pathogens without prior assumptions about causative agents [41]. For samples with high host DNA contamination (e.g., tissue biopsies, skin swabs), amplicon-based methods (16S/ITS) are generally more robust as they require minimal microbial DNA relative to host DNA [39].

Experimental Protocols

Universal Sample Preparation Guidelines

Proper sample handling is critical for all sequencing methods to ensure nucleic acid integrity and representative microbial community preservation. The following protocols apply across all sequencing approaches:

- Sterility: Use sterile collection containers and tools to prevent contamination from environmental microbes [36] [37].

- Temperature Control: Freeze samples immediately at -20°C or -80°C after collection. For field collections, use liquid nitrogen or specialized preservation buffers (e.g., RNAlater) when immediate freezing isn't possible [36] [37].

- Time Considerations: Process or freeze samples as quickly as possible after collection—ideally within hours. When immediate processing isn't feasible, temporary storage at 4°C is acceptable for up to 24 hours [36] [37].

- Aliquoting: Aliquot samples before freezing to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which degrade DNA and introduce bias [36] [37].

DNA Extraction Protocols

Table 2: DNA extraction methods for different sample types

| Sample Type | Recommended Kit | Critical Modifications | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Stool | NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel) [34] | Increased bead-beating time (5-10 min) for tough Gram-positive bacteria | Fluorometric quantification (Qubit), check for PCR inhibitors |

| Soil/Environmental | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) [38] | Additional humic acid removal steps, extended lysis | 260/280 ratio ~1.8, 260/230 >2.0 |

| Fungal Cultures | CTAB-based extraction [38] | Lyticase pretreatment for cell wall degradation, RNAse treatment | High molecular weight on gel electrophoresis |

| Low Biomass (skin, water) | DNeasy PowerLyzer Powersoil (Qiagen) [34] | Carrier RNA in elution buffer, reduced elution volume | Minimum 1ng/μL for amplicon, 10ng/μL for shotgun |

Standardized DNA Extraction Protocol

The following protocol is adapted for diverse sample types with specific modifications for different sequencing approaches:

Cell Lysis:

DNA Precipitation:

DNA Purification:

Library Preparation Protocols

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing (V4 Region)

This protocol targets the V4 hypervariable region using primers 515F/806R for optimal bacterial community coverage [38]:

First-Stage PCR:

- Reaction mix: 2.5μL 10X buffer, 1μL dNTPs (10mM), 0.5μL each primer (10μM), 0.125μL HotStart polymerase, 2μL template DNA, 18.375μL PCR-grade water

- Cycling conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 25 cycles of: 95°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s; final extension 72°C for 5 min [38]

Indexing PCR:

- Use dual indexing approach to minimize index hopping

- 8 cycles with indexing primers [38]

Cleanup and Normalization:

- Clean amplified DNA using magnetic beads (0.8X ratio)

- Quantify using fluorometry (Qubit)

- Pool equimolar amounts of each sample [38]

ITS Sequencing (ITS2 Region)

This protocol specifically targets the fungal ITS2 region for fungal community analysis:

PCR Amplification:

- Use primers ITS3/ITS4 targeting the ITS2 region

- Reaction mix similar to 16S protocol with modified cycling: 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of: 95°C for 30s, 52°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s; final extension 72°C for 5 min [38]

Library Preparation:

- Follow similar cleanup and pooling strategy as 16S protocol