A Comprehensive Guide to Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a systematic comparison of microbial biomass measurement techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of microbial biomass measurement techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, detailed methodologies, troubleshooting for common challenges, and rigorous validation approaches. By synthesizing current research, the review aims to serve as a definitive guide for selecting, optimizing, and validating the most appropriate biomass quantification method for specific experimental contexts, from environmental soil analysis to clinical biofilm assessment and pharmaceutical development.

Understanding Microbial Biomass: Core Concepts and Why Measurement Matters

Defining Microbial Biomass and Its Significance in Ecosystems and Industry

Microbial biomass refers to the total mass of living microorganisms—including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa—in a given habitat or ecosystem, often expressed in terms of living or dry weight per unit area or volume [1]. In soil, it represents the living component of soil organic matter, excluding soil animals and plant roots [2] [3]. Although it typically constitutes less than 5% of total soil organic matter, microbial biomass acts as a critical labile pool of carbon and nutrients, driving essential ecosystem processes such as decomposition, nutrient cycling, and soil structure formation [2].

Its significance extends from fundamental ecosystem functioning to various industrial applications. In ecosystems, microbial biomass is a key indicator of soil health and plays a vital role in carbon sequestration and nutrient supply to plants [4]. In industrial contexts, microbial biomass serves as a foundation for producing biofuels, bioplastics, biopharmaceuticals, and other valuable bioproducts through advanced biotechnological processes [5] [6].

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods

Accurately quantifying microbial biomass is fundamental to both ecological research and industrial biotechnology. However, the choice of measurement method can significantly influence results and their interpretation. The following section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of prominent techniques.

Table 1: Overview of Major Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Measurable Parameters | Throughput | Relative Cost | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE) [2] [7] | Cell lysis via chloroform vapor; quantification of extracted cellular components. | Microbial C (ΔCmic), Microbial N (ΔNmic) | Medium | Low to Medium | Robust, established "gold standard"; provides nutrient pool data. | Susceptible to interference (e.g., from biochar); time-consuming. |

| Chloroform Fumigation-Incubation (FI) [2] [7] | Cell lysis via chloroform; quantification of CO₂ from lysed cell consumption. | Microbial C (ΔCmic) | Low | Low | Well-established historical method. | Even more susceptible to interference than FE; long incubation. |

| Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) Analysis [3] [8] | Extraction and quantification of membrane phospholipids, which degrade rapidly upon cell death. | Total microbial biomass, Fungal/Bacterial biomass, Community structure (low resolution). | Low | High | Measures living biomass directly; provides community composition data. | High cost; complex, variable protocols between labs [8]. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) [8] | Amplification and quantification of biomarker genes (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria). | Gene copy abundance (Bacterial, Fungal). | High | Medium | High specificity; targets specific taxonomic groups. | Results vary with DNA extraction & primer choice; semi-quantitative. |

| Droplet-Digital PCR (ddPCR) [8] | Absolute quantification of biomarker genes via endpoint PCR in partitioned droplets. | Absolute gene copy number (Bacterial, Fungal). | High | High | Superior precision and repeatability vs. qPCR; less susceptible to inhibition. | Narrower dynamic range than qPCR; higher cost [8]. |

| COâ‚‚ High Pressurization (CO2HP) [7] | Cell lysis via high-pressure COâ‚‚; subsequent C measurement. | Microbial C (via extraction or incubation). | Medium | Research Stage | Novel approach. | CO2HP-I method can overestimate biomass due to COâ‚‚ adsorption/desorption [7]. |

Experimental Data and Method Selection

Recent comparative studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of these methods, guiding researchers in selecting the most appropriate technique.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Fungi-to-Bacteria (F/B) Ratio Measurement Methods [8]

| Method | Precision | Repeatability | Correlation with PLFA | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLFA Analysis | High | High | Benchmark | Gold standard for reliable F/B ratio and microbial abundance. |

| Droplet-Digital PCR (ddPCR) | High | High | Strong correlation | Preferred for precise, absolute quantification of gene abundance. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Medium | Medium | Weaker correlation | Viable alternative if ddPCR is unavailable; requires careful calibration. |

| microBIOMETER | N/A | N/A | Poor correlation for F/B | Low-cost, rapid assessment of total microbial biomass only. |

A 2025 method comparison study concluded that PLFA and ddPCR provided the most reliable outcomes for assessing microbial abundance and the fungi-to-bacteria ratio, with PLFA being the most precise and repeatable [8]. While tools like microBIOMETER offer a low-cost option for estimating total microbial biomass, they did not match the reliability of PLFA for determining community composition [8].

Method selection can also be influenced by soil amendments. A 2025 study demonstrated that biochar, depending on its type and application rate, can interfere with traditional chloroform-based methods (FE and FI) and the novel CO2HP method, potentially leading to over- or underestimation of microbial carbon [7]. This highlights the necessity of validating methods in the context of specific experimental conditions.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, detailed protocols for two common and one emerging method are outlined below.

Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE)

The FE method is a widely used and robust technique for estimating soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen [2].

Workflow Diagram: Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction

Materials & Reagents:

- Soil Sample: Fresh, pre-incubated soil, sieved (<2 mm) and adjusted to a standard moisture level.

- Chloroform (CHCl₃): Ethanol-free, highly pure.

- Potassium Sulfate (Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„) Extraction Solution: 0.5 M.

- Vacuum Desiccator: With porcelain plate.

- Beakers: For soil portions and extraction.

- Organic Carbon Analyzer: e.g., TOC analyzer.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Divide a fresh soil sample (equivalent to 25-50 g oven-dry weight) into two portions.

- Fumigation: Place one portion in a vacuum desiccator alongside a beaker containing ~50 ml of chloroform and a few anti-bumping granules. Evacuate the desiccator until the chloroform boils vigorously. Maintain the vacuum and incubate in the dark at 25°C for 24 hours.

- Control: Keep the second, non-fumigated portion in a sealed container at 25°C for the same duration.

- CHCl₃ Removal: After fumigation, repeatedly evacuate the desiccator to remove all chloroform fumes.

- Extraction: Transfer both the fumigated and non-fumigated soils to separate flasks. Add 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ solution (typically at a 1:4 soil-to-solution ratio). Shake vigorously for 30-60 minutes.

- Filtration/Clarification: Filter or centrifuge the extracts to obtain a clear solution.

- Analysis: Determine the organic carbon (and nitrogen, if desired) concentration in both extracts using a suitable analyzer.

- Calculation: Calculate the microbial biomass C (ΔCmic) using the formula: ΔCmic = (Cfumigated - Cnon-fumigated) / kEC, where kEC is a conversion factor, typically 0.45 [2].

Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) Analysis

PLFA analysis measures membrane phospholipids, which are indicators of viable microbial biomass and community structure [8].

Workflow Diagram: PLFA Analysis

Materials & Reagents:

- Extraction Solvents: Single-phase extraction buffer (e.g., Citrate buffer, Methanol, Chloroform).

- Solid-Phase Extraction Columns: Silica-bonded columns.

- Derivatization Reagents: Mild alkaline methanol reagent for transmethylation.

- Internal Standards: Known amounts of specific PLFAs not found in the sample.

- Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS): For separation and detection.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Lipid Extraction: Extract total lipids from the soil sample using a single-phase mixture of citrate buffer, methanol, and chloroform. Shake for several hours.

- Phase Separation: Split the extract into polar and non-polar phases by adding citrate buffer and chloroform. The lipids are in the organic (chloroform) phase.

- Fractionation: Concentrate the lipid extract and load it onto a solid-phase extraction column. Elute the neutral lipids, glycolipids, and phospholipids sequentially. The phospholipid fraction is collected.

- Transmethylation: Subject the phospholipid fraction to mild alkaline methanolysis to convert the phospholipids into Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs).

- GC-MS Analysis: Inject the FAME samples into a GC-MS system. The FAMEs are separated by the gas chromatograph and identified/quantified by the mass spectrometer.

- Data Analysis: Identify specific PLFA biomarkers (e.g., 18:2ω6 for fungi, specific branched-chain for bacteria) and quantify them. Total microbial biomass is estimated from the sum of all PLFAs, and the fungi-to-bacteria ratio is calculated from the respective biomarkers [3] [8].

Droplet-Digital PCR (ddPCR)

ddPCR provides absolute quantification of microbial abundance without the need for a standard curve, offering high precision [8].

Workflow Diagram: ddPCR Workflow

Materials & Reagents:

- Extracted DNA: From soil samples.

- ddPCR Supermix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and other necessary components.

- Primers and Probes: Sequence-specific for bacterial 16S rRNA genes, fungal ITS or 18S rRNA genes, etc.

- Droplet Generation Oil & Cartridges: For water-in-oil emulsion.

- ddPCR System: Including droplet generator, thermal cycler, and droplet reader.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- PCR Mix Preparation: Combine the DNA template with the ddPCR supermix, fluorophore-labeled probes (e.g., FAM, HEX), and forward and reverse primers for the target gene (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria).

- Droplet Generation: Load the PCR mix and droplet generation oil into a designated cartridge. The droplet generator partitions the sample into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets.

- PCR Amplification: Transfer the droplets to a PCR plate and run a standard thermal cycling protocol. In droplets containing the target DNA, amplification occurs, leading to a fluorescent signal.

- Droplet Reading: After amplification, the droplet reader flows each droplet individually past a fluorescence detector. Droplets are counted as positive or negative based on their fluorescence amplitude.

- Absolute Quantification: The concentration of the target DNA in the original sample is calculated based on the fraction of positive droplets using Poisson statistics, providing an absolute copy number per unit of DNA or soil [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Biomass Studies

Selecting the appropriate reagents and materials is critical for the accuracy and reproducibility of microbial biomass measurements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) [2] | Cell membrane disruption and lysis of microorganisms. | Chloroform Fumigation (FE, FI). | Must be ethanol-free for maximum efficacy; requires careful handling and fume hood use. |

| Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ Solution [2] | Extraction of soluble organic carbon and nitrogen from lysed microbial cells. | Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE). | Standardized molarity (e.g., 0.5 M) is critical for cross-study comparisons. |

| PLFA Internal Standards [8] | Quantification and correction for extraction efficiency losses. | Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) Analysis. | Must be a non-indigenous PLFA (e.g., 19:0 PC) added at the very beginning of extraction. |

| PCR Primers & Probes [8] | Target-specific amplification of microbial biomarker genes. | qPCR and ddPCR. | Specificity is paramount (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria, ITS/18S for fungi); design impacts results. |

| Droplet Generation Oil [8] | Creates stable, monodisperse droplets for partitioning the PCR reaction. | Droplet-Digital PCR (ddPCR). | Must be compatible with the specific ddPCR instrument and thermal cycling conditions. |

Microbial biomass is a cornerstone of ecosystem stability and a versatile driver of industrial innovation. Its accurate quantification is non-trivial, with the optimal method depending heavily on the research question, budget, and required resolution. For broad ecological assessments of total living biomass and functional groups, PLFA analysis remains the most robust and informative benchmark [8]. For studies targeting specific taxonomic groups with high precision, ddPCR emerges as a superior molecular tool [8]. Researchers must be aware of potential interferences, such as those from soil amendments like biochar, which can compromise even established methods like FE and FI [7]. As the field advances, the integration of genomic data with ecosystem models promises a deeper, more predictive understanding of microbial functions across diverse environments [9].

Soil health is fundamentally governed by the living component beneath our feet—the soil microbiome. This diverse community of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and other microorganisms acts as the primary engine driving nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and ecosystem resilience [10] [11]. Despite its critical importance, this biological system has historically functioned as a "black box," with its intricate processes largely obscured from scientific view [10]. The quantification of soil microbial biomass provides a crucial index for peering into this black box, offering researchers a measurable proxy for understanding soil biological activity and its relationship to overall ecosystem function [11] [12].

Recent methodological advances have transformed our capacity to measure and interpret this living soil component. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the predominant techniques used to estimate microbial biomass, evaluating their applications, limitations, and performance across different research contexts. For soil scientists, ecologists, and environmental researchers, selecting an appropriate biomass quantification strategy is paramount for accurately assessing soil health status and predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change [12] [13].

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods

Performance Metrics and Applicability

Table 1: Comparison of Major Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods

| Method | What It Measures | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Throughput | Cost | F/B Ratio Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (CFE) | Total microbial biomass C and N via cell lysis [14] [15] | Considered reliable and interpretable; Direct biomass measurement [12] [15] | Labor-intensive; Requires toxic chemicals [12] | Low | Low-Moderate | No |

| Phospholipid Fatty Acid Analysis (PLFA) | Microbial biomass and community structure via membrane lipids [8] | Gold standard for F/B ratios; High precision and repeatability [8] [15] | Significant inter-laboratory variability; Complex protocols [8] | Moderate | High | Excellent |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Microbial abundance via gene copy numbers [8] | High sensitivity; Taxon-specific quantification | Inhibition biases; Narrow dynamic range [8] | High | Moderate | Good with limitations |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute microbial abundance via nucleic acid partitioning [8] | Better precision than qPCR; Reduced inhibition effects [8] | Narrower dynamic range than qPCR [8] | High | Moderate-High | Good with limitations |

| Substrate-Induced Respiration (SIR) | Active microbial biomass via COâ‚‚ evolution [12] | Simple; High throughput; Functional activity measure [12] | Not suitable for all soil types (e.g., peat) [12] | High | Low | No |

| microBIOMETER | Total microbial biomass via turbidity and F/B ratio [8] | Rapid, low-cost, field-deployable [8] | Does not match PLFA results for F/B ratio [8] | Very High | Low | Limited reliability |

Method Selection Guidelines Based on Research Objectives

Table 2: Method Recommendations for Specific Research Applications

| Research Objective | Recommended Primary Method(s) | Complementary Method(s) | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Microbial Biomass Assessment | CFE, SIR [12] [15] | PLFA, DNA quantification [15] | CFE provides robust biomass C estimates; SIR reflects active portion [12] |

| Fungi-to-Bacteria Ratio Determination | PLFA [8] | ddPCR, qPCR [8] | PLFA remains gold standard; molecular methods show promise but with biases [8] |

| High-Throughput Screening | SIR, microBIOMETER [12] [8] | POXC, MinC [12] [16] | Trade-offs between accuracy and throughput must be considered [12] |

| Microbial Community Modeling | PLFA, DNA-based methods [15] | CFE for calibration [15] | Correlation equations exist to relate different methods [15] |

| Agricultural Management Impact Studies | CFE, PLFA, SIR [12] | Enzyme assays, respiration metrics [12] [13] | Seasonal variation requires temporal sampling design [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (CFE) for Microbial Biomass C and N

The CFE method provides a robust estimation of total microbial biomass carbon (Cₘᵢð’¸) and nitrogen (Nₘᵢð’¸) through direct cell lysis [14] [15]. The standard protocol involves:

Sample Preparation: Fresh soil samples are sieved (<2 mm) and adjusted to approximately 50-60% water holding capacity. Visible organic debris, roots, and stones are removed [14].

Fumigation Process: Duplicate soil samples (30 g each) are exposed to ethanol-free chloroform vapor for 24 hours in a vacuum desiccator maintained at 25°C in darkness [14].

Extraction and Analysis: Both fumigated and non-fumigated control samples are extracted with 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ (1:4 w/v) by shaking for 30 minutes at 200 rpm. The extracts are filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper [14].

Calculation: Organic carbon in the extracts is determined by potassium dichromate oxidation and titration with ferrous ammonium sulfate. Cₘᵢ𒸠is calculated as: Cₘᵢ𒸠= (ECₑₓₜᵣâ‚ð’¸â‚œâ‚‘ð’¸ - ECð’¸â‚’ₙₜᵣₒₗ) / kEC, where EC represents extractable C and kEC is the extraction efficiency factor (typically 0.45) [14].

Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) Analysis

PLFA analysis characterizes microbial biomass and community structure based on membrane lipid biomarkers [8]. The standardized protocol consists of six key stages:

Sample Storage and Preparation: Soils are freeze-dried and stored at -80°C to preserve lipid integrity [8].

Total Lipid Extraction: Lipids are extracted using a single-phase chloroform-methanol-citrate buffer mixture (1:2:0.8 v/v/v) [8].

Lipid Class Separation: The total lipid extract is fractionated into neutral lipids, glycolipids, and phospholipids using solid-phase extraction silica columns [8].

Transmethylation: Phospholipids are subjected to alkaline methanolysis to form fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) [8].

GC-MS Analysis: FAMEs are separated, identified, and quantified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [8].

Data Analysis: Biomarker fatty acids are assigned to specific microbial groups (e.g., 18:2ω6c for fungi, 16:1ω7c for bacteria) [8].

DNA-Based Quantification (qPCR/ddPCR)

Molecular approaches target taxonomic marker genes to estimate microbial abundance [8]:

DNA Extraction: Commercial soil DNA extraction kits are employed with bead-beating for cell lysis. Clay-rich soils may require modified protocols to improve extraction efficiency [15].

Primer Selection: Bacterial abundance is typically quantified using 16S rRNA gene primers (e.g., 515F/806R), while fungal abundance targets 18S rRNA gene or ITS region primers [8].

qPCR Protocol: Reactions contain template DNA, primer pairs, and SYBR Green master mix. Thermal cycling conditions include initial denaturation (95°C, 3 min), followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 30 s), annealing (55°C, 30 s), and extension (72°C, 30 s) [8].

ddPCR Protocol: The reaction mixture is partitioned into ~20,000 nanodroplets. End-point PCR amplification is followed by droplet reading to determine positive and negative reactions, enabling absolute quantification without standard curves [8].

Methodological Decision Framework and Workflows

Analytical Workflow for Comprehensive Soil Health Assessment

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Biomass Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Application | Specific Function | Method(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-free Chloroform | Cell membrane disruption | Lyses microbial cells to release cytoplasmic contents | CFE [14] |

| Potassium Sulfate (0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Soluble carbon extraction | Extracts organic C from fumigated and non-fumigated soils | CFE [14] |

| Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Lipid extraction medium | Maintains pH during phospholipid extraction | PLFA [8] |

| Chloroform-Methanol Mixture | Total lipid extraction | Single-phase extraction of membrane lipids from soil | PLFA [8] |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Standards | GC-MS calibration | Quantitative standards for fatty acid identification and quantification | PLFA [8] |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | DNA quantification | Fluorescent intercalating dye for qPCR amplification detection | qPCR [8] |

| Taxon-Specific Primers | Target amplification | Amplifies 16S rRNA (bacteria) or 18S/ITS (fungi) marker genes | qPCR/ddPCR [8] |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Reaction partitioning | Creates nanodroplets for absolute quantification in ddPCR | ddPCR [8] |

The journey to unravel soil's "black box" requires sophisticated methodological approaches that balance accuracy, practicality, and interpretive power. No single method currently provides a perfect solution for all research contexts, but strategic integration of complementary approaches can yield comprehensive insights into soil microbial communities and their functional contributions to ecosystem health [15] [13].

PLFA analysis remains the gold standard for fungi-to-bacteria ratio determination, while CFE provides robust estimates of total microbial biomass carbon [8] [14]. Emerging molecular techniques like ddPCR offer promising alternatives with enhanced precision, though they have not yet surpassed established methods for all applications [8]. For high-throughput screening, SIR and commercial kits like microBIOMETER provide practical options, though with acknowledged trade-offs in accuracy [12] [8].

Future methodological development should focus on standardizing protocols across laboratories, improving the interpretability of biomass measurements within soil health frameworks, and establishing clearer relationships between microbial indicators and ecosystem functions [12] [17]. As climate change and sustainable land management become increasingly pressing concerns, refining these "black box" indices will be essential for monitoring soil health and maintaining the ecosystem services upon which terrestrial life depends [10] [11].

Quantifying microbial biomass and its molecular components is a foundational step in research and drug development, yet the path from cell lysis to final data interpretation is fraught with challenges. The initial steps of cellular disruption and nucleic acid extraction introduce significant variability that can confound downstream analysis and signal interpretation. This guide objectively compares common methodological approaches by synthesizing experimental data from recent studies, providing a framework for selecting optimal protocols based on specific research goals.

The process of quantifying microbial elements involves a multi-stage pipeline, each stage of which introduces potential bias. It begins with cell lysis, where the cellular envelope is disrupted to release internal components, followed by extraction and purification of target molecules (e.g., DNA, RNA, metabolites). Finally, the detection and signal interpretation stage aims to correlate the measured signal with absolute biological quantities. Challenges at any one stage can compromise the entire experiment. This is particularly critical in low-biomass environments—such as certain human tissues, atmospheric samples, or treated drinking water—where the target signal is minimal and the risk of contamination or amplification bias is high [18].

The following sections break down this pipeline, comparing the efficiency of different techniques and providing detailed experimental protocols to aid in method selection and reproducibility.

Part 1: Comparative Analysis of Cell Lysis and Extraction Methods

The choice of cell lysis and subsequent extraction method has a profound impact on the yield, quality, and representativeness of the isolated analytes. The optimal method often depends on the cell type, the target molecule, and the desired downstream application.

Cell Lysis Method Efficiency

Cell lysis methods are broadly classified as mechanical, chemical, or enzymatic. Mechanical methods are often more effective for tough cell walls, while chemical and enzymatic methods can be milder and more specific.

Table 1: Comparison of Cell Lysis Methods for Different Microorganisms

| Lysis Method | Mechanism of Action | Optimal Cell Type | Efficiency / Key Finding | Major Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bead Beating (Horizontal) [19] | Physical grinding using beads in a vortex adapter. | Candida albicans (Yeast) | 100% lysis efficiency observed with RiboPure Lysis Buffer. | Generation of significant heat, requiring cooling. |

| Bead Beating (Vertical) [19] | Manual vortexing with beads in a vertical tube position. | Candida albicans (Yeast) | 83% lysis efficiency with RiboPure Lysis Buffer. | Less efficient than horizontal orientation due to reduced shearing area. |

| Lyticase Treatment [19] | Enzymatic degradation of the yeast cell wall. | Candida albicans (Yeast) | 95% lysis efficiency after 1 hour incubation. | Less efficient than optimized bead beating; longer processing time. |

| High-Pressure Homogenizer [20] | Shearing forces from forcing cells through a narrow orifice under high pressure. | Bacteria, Fungi (Large scale) | Protein release follows first-order kinetics; suitable for high throughput. | Heat generation; potential degradation of some enzymes [20]. |

| Detergent-Based Lysis [21] | Solubilizes membrane lipids and proteins to create pores. | Mammalian cells, Bacteria (for proteins) | Rapid lysis; choice of ionic (strong) or non-ionic (mild, protein-preserving) detergents. | Can interfere with downstream protein assays; may denature proteins. |

| Freeze-Thaw Cycling [21] | Formation of ice crystals that rupture the membrane. | Mammalian cells | Simple and widely used; helps preserve cellular proteins/nucleic acids. | Ineffective for cells with rigid walls; can cause cold denaturation of proteins. |

Impact of Lysis and Detachment on Metabolomic Profiles

Beyond simple efficiency, the method of preparing cells for analysis can drastically alter the metabolic profile observed. A 2022 untargeted metabolomics study on MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells highlights this point.

Table 2: Impact of Sample Preparation on Metabolomic Profiles in MDA-MB-231 Cells [22]

| Experimental Factor | Compared Methods | Effect on Metabolic Profile | Key Metabolic Pathways Significantly Altered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detachment Method | Trypsinization vs. Cell Scraping | The greatest effect on metabolic profiles, with a clear distinction between methods. | Tyrosine metabolism, Urea cycle/amino group metabolism, Arginine and proline metabolism, Vitamin B6 metabolism, Tryptophan metabolism. |

| Lysis Method | Homogenizer Beads vs. Freeze-Thaw Cycling | A lesser, but still significant, effect on profiles. | Primarily pathways related to fatty acids (e.g., de novo fatty acid biosynthesis, fatty acid activation). |

Supporting Experimental Data: The study found that scraped samples generally showed higher abundances of amino acids (e.g., histidine, leucine, phenylalanine) and urea cycle metabolites. In contrast, trypsinized samples had higher levels of lactate and acylcarnitines [22]. No single method was universally superior, underscoring the need for method selection based on the metabolite classes of interest.

Methods for Estimating Microbial Biomass

For environmental samples like soil, estimating total microbial biomass presents its own set of challenges, with different methods offering varying trade-offs between throughput, cost, and accuracy.

Table 3: Comparison of Proxies for Soil Microbial Biomass Estimation [23]

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (CFE) | Measures C released from lysed microbial cells. | Considered a "gold standard"; extensive historical use and evaluation. | Labor-intensive; uses toxic reagents; lacks taxonomic resolution; accuracy varies with soil type. |

| Phospholipid Fatty Acids (PLFA) | Quantifies lipids from living cell membranes. | Measures viable biomass; provides broad taxonomic resolution (e.g., fungi vs. bacteria). | Resource-intensive; does not account for Archaea; overlap in biomarkers can reduce accuracy. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Measures abundance of a universal marker gene (e.g., 16S rRNA). | High throughput; reduced reagent use; can estimate fungal:bacterial ratios. | Affected by variable gene copy number per cell; vulnerable to "relic DNA" from dead cells. |

| Total DNA Yield | Measures total DNA extracted from a soil sample. | Rapid; potentially high throughput; low soil mass requirement. | Affected by extraction efficiency and "relic DNA"; relationship to live biomass not robust. |

| Bacterial-to-Host DNA Ratio (B:H) [24] | Estimates gut bacterial biomass from metagenomic data using host DNA as an internal standard. | Simple, low-cost; uses existing sequencing data; no extra experiments needed. | Primarily applicable to stool metagenomes where host DNA is present. |

Part 2: Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this guide.

Objective: To compare the efficiency of different cell lysis methods for yeast cells stored in RNAlater. Materials:

- Candida albicans cells (10^7 cells in log growth phase)

- RiboPure Lysis Buffer (RPLB)

- Zirconium beads (0.5 mm)

- Vortex mixer with a horizontal vortex adapter

- Lyticase Lysis Buffer (LLB) with 2 U/μl lyticase

- Microscope for visualization

Methodology:

- Preparation: Aliquot 1 mL of C. albicans cell suspension (10^7 cells) and store at -80°C in RNAlater or a control medium (TSB with 15% glycerol).

- Lysis by Bead Beating:

- Thaw the aliquot.

- Add cells to a tube containing RiboPure Lysis Buffer and 0.5 mm zirconium beads.

- Secure the tube in a horizontal vortex adapter.

- Vortex at maximum speed for 10 minutes.

- Lysis by Lyticase Treatment (Control):

- Incubate cells in Lyticase Lysis Buffer (2 U/μl) for 1 hour at the recommended temperature.

- Efficiency Assessment:

- Use microscopic visualization to count lysed versus intact cells.

- Calculate the percentage of cell lysis for each method.

Reported Result: For cells stored in RNAlater, horizontal bead beating in RPLB resulted in 73.5% cell lysis efficiency, which was superior to the other methods tested under the same conditions [19].

Objective: To investigate the effects of different detachment and lysis methods on the metabolomic profile of MDA-MB-231 cells. Materials:

- MDA-MB-231 cell line

- Trypsin-EDTA solution for detachment

- Cell scrapers

- Homogenizer beads

- Liquid nitrogen for freeze-thaw cycles

- UHPLC-HRMS system for untargeted metabolomics

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Grow MDA-MB-231 cells to 80-90% confluence.

- Detachment (Two Methods):

- Trypsinization: Detach cells using a standard trypsin-EDTA solution.

- Scraping: Mechanically detach cells using a sterile cell scraper.

- Lysis (Two Methods):

- Bead Homogenization: Lyse cell pellets using homogenizer beads in a mechanical homogenizer.

- Freeze-Thaw Cycling: Subject cell pellets to multiple cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing.

- Metabolite Extraction & Analysis:

- Extract metabolites using a standardized solvent system.

- Analyze using UHPLC-HRMS.

- Process data with peak alignment, normalization, and multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, OPLS-DA).

- Identify pathways using software like MetaboAnalyst.

Part 3: Visualizing Workflows and Challenges

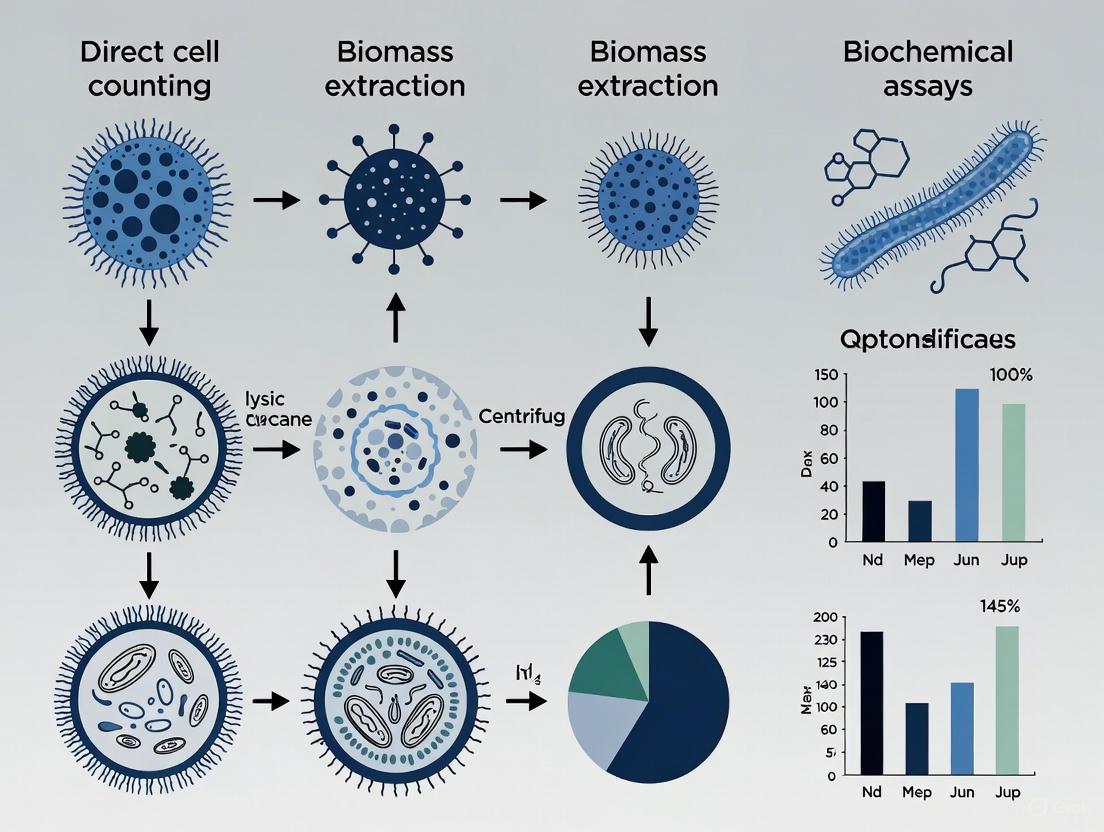

The following diagrams outline the logical relationships and workflows in microbial quantification and the specific challenges in low-biomass studies.

Part 4: The Scientist's Toolkit - Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting the right reagents is critical for successful and reproducible cell lysis and biomass quantification.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Lysis and Biomass Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Principle of Action | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| RiboPure Lysis Buffer [19] | A chemical buffer designed for efficient disruption of cellular membranes, often used in conjunction with mechanical methods. | Effective for lysing tough cell walls, such as those of yeast (e.g., Candida albicans). |

| Zirconium Beads (0.5 mm) [19] | Inert, durable beads that provide physical grinding action during bead beating to break open cells. | Mechanical lysis of microbial and fungal cells in bead mills. |

| Lyticase [19] | An enzyme that specifically targets and degrades the beta-glucan in yeast cell walls. | Enzymatic lysis of yeast cells; often a component of standard DNA/RNA extraction kits. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [21] | A strong ionic detergent that solubilizes lipids and proteins in the cell membrane, leading to complete lysis and protein denaturation. | General purpose cell lysis; plasmid DNA preparation; protein gel electrophoresis. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) [21] | Milder detergents that disrupt lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions but do not denature proteins. | Cell lysis where maintaining protein native structure and function is critical. |

| RNAlater [19] | A RNA-stabilizing solution that permeates tissues and cells to stabilize and protect cellular RNA. | Stabilization of RNA in cells and tissues prior to RNA extraction, preventing degradation. |

| Chloroform [23] | An organic solvent used in the chloroform fumigation-extraction (CFE) method to lyse microbial cells and release cellular carbon. | Estimation of soil microbial biomass carbon. |

| Bead Mill Homogenizer [20] | Equipment that uses rapid shaking with beads to disrupt cells through physical shearing and impact. | High-throughput mechanical lysis of a wide range of cell types, including bacteria and yeast. |

| High-Pressure Homogenizer [20] | Equipment that forces a cell suspension through a narrow valve under high pressure, shearing the cells. | Large-scale disruption of cells for industrial or extensive research applications. |

| WH-4-023 | WH-4-023, CAS:837422-57-8, MF:C32H36N6O4, MW:568.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Sarmentose | D-Sarmentose, CAS:13484-14-5, MF:C7H14O4, MW:162.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey from cellular lysis to accurate signal interpretation is complex and heavily influenced by methodological choices. As the comparative data shows, no single lysis or quantification method is universally superior. The decision between mechanical, chemical, or enzymatic lysis, or the selection of a biomass estimation proxy, must be guided by the specific cell type, the analyte of interest, and the required balance between throughput and accuracy. Furthermore, the challenges of working with low-biomass samples necessitate rigorous contamination controls throughout the entire workflow. By understanding the trade-offs and experimental evidence outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can make more informed decisions, leading to more reliable and interpretable quantification data.

In microbial research, accurately determining microbial biomass is fundamental to understanding ecosystem dynamics, biotechnological applications, and environmental processes. The methodologies for quantification can be broadly categorized into biomass-based systems, which measure collective activity or chemical components of the microbial community, and molecular-based systems, which target specific cellular components or genetic material for enumeration and identification [25]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodological categories, detailing their protocols, performance, and appropriate applications to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal tool for their specific research context.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance metrics, and typical applications of the major method categories.

Table 1: Comparison of Biomass-Based and Molecular-Based Methods for Microbial Biomass Estimation

| Method Category | Specific Method | Principle of Operation | Key Measured Parameter | Reported Correlation/Performance | Throughput | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass-Based | Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE) | Measures C & N flush from lysed microbial cells [26]. | Microbial Biomass Carbon (MBC) [26] | Correlates with DNA yield, PLFA, qPCR [15]. Dominates ~83% of MBC studies [26]. | Medium | Soil health studies; Ecosystem monitoring [14]. |

| Biomass-Based | Substrate-Induced Respiration (SIR) | Measures initial respiration response to added glucose [26]. | Basal Respiration Rate | Used in ~17% of studies; rapid response indicator [26]. | High | Metabolic activity assessment; quick soil health checks [14]. |

| Biomass-Based | Oxygen Uptake Rate (OUR) | Measures oxygen consumption by microbes under non-limited growth [25]. | Model Biomass (Activity-based) [25] | Correlated with DAPI cell count (69% of model-predicted biomass) [25]. | Medium | Wastewater transformation modeling; engineering applications [25]. |

| Molecular-Based | Phospholipid Fatty Acids (PLFA) | Quantifies membrane lipids as indicator of live biomass [15]. | Total PLFA concentration | Correlates with CFE; better for total biomass than fungi/bacteria parsing [15]. | Medium | Community structure analysis; broad biomass estimation [15]. |

| Molecular-Based | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Quantifies gene copies of target genes (e.g., 16S rRNA) [15]. | Gene Copy Number (GCN) | Correlates with CFE; improved with clay content correction [15]. | High | Targeted quantification of specific microbial groups. |

| Molecular-Based | Total DNA Yield | Extracts and quantifies total DNA from a soil sample [15]. | DNA Concentration (μg/g soil) | Correlates strongly with CFE [15]. | High | Total microbial load; pre-screening for molecular work. |

| Molecular-Based | Microscopy with Staining (DAPI/AO) | Fluorescent stains bind to DNA for direct cell counting [25]. | Total Cell Counts | DAPI count was 69% of model biomass from OUR [25]. | Low | Direct enumeration; distinguishing cell states [25]. |

Experimental Protocols

Key Biomass-Based Protocol: Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE)

The FE method is a cornerstone technique for estimating soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and nitrogen (MBC) [26].

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. A moist soil sample (>40% water holding capacity) is divided into two subsamples. Any visible organic debris, roots, or stones are removed, and the soil is sieved (<2 mm) [14].

- Step 2: Fumigation. One subsample is placed in a desiccator with ethanol-free chloroform (stabilized with alternatives like β-isoamylene) and fumigated for 24 hours at 25°C in the dark. This step lyses microbial cells [26] [14].

- Step 3: Chloroform Removal. After fumigation, the chloroform vapor is completely evacuated from the desiccator by repeated vacuum extraction [26].

- Step 4: Extraction. Both the fumigated and the non-fumigated (control) subsamples are extracted with 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ at a soil-to-solution ratio of 1:4 (w/v) for 30 minutes on a reciprocating shaker at 200 rpm [26] [14].

- Step 5: Filtration and Analysis. The soil suspensions are filtered (e.g., through Whatman No. 42 filter paper). The organic carbon in the extracts is then determined, often by oxidation with 0.4N K₂Cr₂O₇ and back-titration with ferrous ammonium sulfate (Walkley-Black method) [14].

- Step 6: Calculation. MBC is calculated from the difference in extractable organic carbon between the fumigated and non-fumigated samples using a conversion factor (k_EC, often 0.45) [26].

- Formula:

MBC = (Organic C_fumigated - Organic C_non-fumigated) / k_EC[14]

- Formula:

Key Molecular-Based Protocol: Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

qPCR is used to quantify the abundance of specific microbial genes (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria) in environmental samples [15].

- Step 1: Total DNA Extraction. Total genomic DNA is extracted from the soil or biomass sample using a commercial kit or standardized protocol (e.g., bead-beating for cell lysis). The efficiency of this step is critical and can be lower in clay-rich soils, requiring corrections in final data analysis [15].

- Step 2: DNA Quantification and Quality Check. The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA are measured using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) or fluorometer (e.g., Qubit).

- Step 3: Preparation of qPCR Reaction. The reaction mixture is prepared to contain:

- Template DNA (typically 1-10 ng/μL)

- Forward and reverse primers specific to the target gene

- Fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan) or DNA-binding dye (e.g., SYBR Green)

- dNTPs, reaction buffer, and a thermostable DNA polymerase

- Step 4: Amplification and Detection. The plate is run in a real-time PCR cycler. The cycle conditions typically are:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3-5 minutes.

- Amplification (40-50 cycles): Denaturation at 95°C for 15-30 seconds, Annealing at primer-specific temperature (50-60°C) for 30-45 seconds, and Extension at 72°C for 30-60 seconds. Fluorescence is measured at the end of each cycle.

- Step 5: Data Analysis. The cycle threshold (Ct) values for each sample are used. The gene copy number in the original sample is determined by comparing the Ct values to a standard curve created from serial dilutions of a known concentration of the target gene [15].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow selection between these two major methodological categories.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for executing the profiled microbial biomass estimation methods.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Biomass Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Methods of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-free Chloroform | Lyses microbial cells during fumigation by destroying cell membrane integrity [26]. | Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE) [26] [14] |

| 0.5 M Potassium Sulfate (Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Saline solution used to extract organic carbon and nitrogen from fumigated and non-fumigated soils [26] [14]. | Chloroform Fumigation-Extraction (FE) [14] |

| DNA Stains (DAPI, Acridine Orange) | Fluorescent dyes that bind to nucleic acids, enabling direct enumeration of total cell counts under microscopy [25]. | Direct Microscopy Enumeration [25] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a stable, isotonic environment for handling and suspending microbial cells without causing osmotic stress. | Various, including cell washing and suspension |

| Lysis Buffers (e.g., with SDS) | Disrupts cell membranes and releases intracellular components, including DNA and proteins, for analysis. | DNA Extraction (for qPCR, GCN) [15] |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades proteins and inactivates nucleases during DNA extraction, protecting the target DNA. | DNA Extraction (for qPCR, GCN) |

| SYBR Green / TaqMan Probes | Fluorescent markers used to detect and quantify amplified DNA products in real-time during qPCR cycles [15]. | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) [15] |

| Chloroform & Methanol Mixture | Organic solvent mixture used for the extraction of phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) from microbial membranes. | Phospholipid Fatty Acids (PLFA) |

| 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine-d70 | 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine-d70, MF:C41H82NO8P, MW:818.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anticancer agent 224 | Anticancer agent 224, MF:C31H39FN2O2S, MW:522.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comparison elucidates that the choice between biomass-based and molecular-based systems is not a matter of superiority but of context. Biomass-based methods like FE and SIR offer a robust, integrative measure of the living microbial pool, making them indispensable for soil health and ecosystem studies [26] [14]. In contrast, molecular-based methods like qPCR and PLFA provide higher resolution for specific groups or total biomass estimation, though they may require corrections for environmental factors like clay content [15]. A strong correlation exists between the data produced by these different categories, such as between FE and total DNA yield or PLFA, validating their collective use in microbial ecology [15]. For a comprehensive understanding, researchers should consider a multi-method approach that leverages the strengths of both categories to validate findings and gain deeper insights into microbial community structure and function.

A Deep Dive into Measurement Techniques: Principles, Protocols, and Applications

For nearly half a century, chloroform-based methods have served as the cornerstone for quantifying soil microbial biomass, a critical parameter for understanding biogeochemical cycling and ecosystem functioning. Among these, the Fumigation-Incubation (FI) and Fumigation-Extraction (FE) methods have emerged as the most widely recognized and applied techniques. The FI method, pioneered by Jenkinson and Powlson in 1976, represented a breakthrough in indirect biomass estimation [27] [26]. Its successor, the FE method (also known as chloroform fumigation-extraction, CFE), developed by Vance et al. in 1987, offered a faster alternative applicable to a wider range of soils [28] [26]. Despite the emergence of modern techniques like phospholipid fatty acid analysis and molecular methods, these "traditional workhorses" maintain their relevance in contemporary soil science, with the FE method dominating current literature and being used in 83.2% of studies on microbial biomass carbon in 2024, compared to 16.5% for FI [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of their performance, protocols, and applications to inform researcher selection.

Both FI and FE methods operate on the same fundamental principle: chloroform fumigation lyses microbial cells, releasing their internal contents, and the quantification of these released components allows for estimation of initial biomass. However, their pathways diverge significantly after fumigation, leading to distinct advantages and limitations.

The Fumigation-Incubation (FI) method involves measuring the respiration response of re-inoculated microbes to the killed biomass. After fumigation and chloroform removal, the soil is inoculated with a small amount of fresh, non-fumigated soil and incubated for 10 days. The respired COâ‚‚ from the decomposition of the dead microbial cells is trapped and measured. The difference in COâ‚‚ production between fumigated and non-fumigated controls is proportional to the initial microbial biomass, using a conversion factor (Kc) of 0.45 [27].

The Fumigation-Extraction (FE) method streamlines this process by directly measuring the cellular components released immediately after fumigation. Following the 24-hour fumigation and fumigant removal, soils are extracted with 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ for 30 minutes. The difference in extractable organic carbon and nitrogen between fumigated and non-fumigated soils is measured, and microbial biomass is calculated using a conversion factor (kEC) of 0.45 for surface soils [28] [27] [26].

Table 1: Core Principle and Workflow Comparison of FI and FE Methods

| Feature | Fumigation-Incubation (FI) | Fumigation-Extraction (FE) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Measures respiration of re-inoculated microbes consuming lysed cells | Directly measures cellular components (C, N, P, S) flushed from lysed cells |

| Post-Fumigation Process | 10-day incubation with inoculum | Immediate chemical extraction with 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ |

| Primary Measurement | COâ‚‚ evolution during incubation | Extractable organic C and total N in solution |

| Key Conversion Factor | Kc = 0.40–0.45 | kEC = 0.45 (for surface soils) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standardized FI Protocol:

- Pre-incubation: Moist soil samples are often pre-incubated for a few days to stabilize microbial activity post-disturbance.

- Fumigation: Soil samples are placed in a desiccator with ethanol-free chloroform and incubated in the dark for 24 hours at 25°C [28].

- Fumigant Removal: Chloroform is removed by repeated evacuation.

- Inoculation & Incubation: Fumigated soils are inoculated with a small aliquot (e.g., 1% w/w) of non-fumigated soil and incubated for 10 days in sealed jars.

- COâ‚‚ Measurement: The COâ‚‚ evolved during incubation is trapped in an alkaline solution (e.g., NaOH) and quantified by titration, or measured via gas chromatography or infrared gas analysis [27].

Standardized FE Protocol:

- Fumigation: As in FI, soil samples are fumigated with ethanol-free chloroform for 24 hours [26].

- Fumigant Removal: Chloroform is completely removed by repeated evacuation. Chloroform stabilized with 2-methyl-2-butene is often used as it is more easily removed [26].

- Extraction: Fumigated and parallel non-fumigated control soils are extracted with 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ (typically at a 1:4 soil-to-extractant ratio) by oscillating shaking at 200 rpm for 30 minutes [26] [14].

- Filtration & Analysis: The extracts are filtered (e.g., through Whatman No. 42 filter paper). The organic carbon in the extracts is then quantified, often by the Walkley-Black method [14] or via a TOC analyzer.

Comparative Performance and Supporting Data

The choice between FI and FE significantly impacts results, workflow, and applicability. Experimental data across diverse soils reveal critical performance differences.

Table 2: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of FI and FE Methods

| Performance Characteristic | Fumigation-Incubation (FI) | Fumigation-Extraction (FE) |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Long (~10 days incubation) [27] | Short (can be completed in ~2 days) [28] [29] |

| Applicable Soil Range | Limited; not suitable for acidic (pH <5), saline, or recently amended soils [28] [27] | Broad; validated for acidic, waterlogged, high OM, and saline soils [28] [29] |

| Measurable Elements | Primarily C and N [27] | C, N, P, and S simultaneously [26] [29] |

| Sensitivity to Soil Conditions | High sensitivity to soil water content, particularly in dry soils [28] | Less sensitive, though adjustments are needed for very dry soils [28] |

| Impact of Fumigation Time | Standardized at 24 hours | C/N release can increase with longer fumigation (up to 10 days), potentially causing 24-hour underestimation [28] |

| Influence of Nutrient Addition | N/A | Robust; not significantly biased by experimental N/P addition in acidic forests [30] |

| Integration with Isotopic Studies | Restricted to 14C, 13C, 15N [27] | Compatible with a wider range (14C, 13C, 15N, 32P, 35S) [27] |

Supporting Experimental Evidence:

- A study on forest soils found that a 1-day fumigation, as used in standard FE, underestimated the maximum flush of microbial C and N by 24% and 18%, respectively, on average, compared to longer fumigation times. This suggests that for some soils, the standard FE protocol may systematically underestimate biomass [28].

- The FE method has been tested for robustness in experimentally fertilized soils. Research in strongly acidified Chinese forests showed that adding nitrogen and phosphorus immediately before fumigation—thus not altering actual biomass—did not significantly bias MBC or MBN measurements, confirming its reliability for nutrient-addition studies [30].

- In a broad-scale comparison across eight soil orders, FE maintained strong correlations with other biomass proxies like PLFA and DNA-based methods, supporting its validity for cross-ecosystem studies [23].

Current Research Context and Method Selection

Within the broader thesis of microbial biomass measurement, FI and FE represent robust, "whole-biomass" approaches compared to specific biomarker methods (e.g., PLFA, ATP) or molecular techniques (e.g., qPCR). While FI was foundational, the scientific community has largely shifted towards FE due to its practicality and wider applicability [26].

The FE method's dominance is evident in its extensive use for calibrating newer models that explicitly incorporate microbial parameters into soil carbon cycling projections [23]. Its ability to provide access to "virtually all elements and organic components stored as CHCl₃-labile compounds" makes it a uniquely comprehensive tool [26]. However, both methods are considered a "black box" as they do not provide taxonomic differentiation between bacterial and fungal biomass, a key limitation addressed by methods like PLFA analysis [23].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Critical Specifications & Hazards |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) | Lyses microbial cells during fumigation by destroying cell membrane integrity. | Must be ethanol-free. Stabilized with 2-methyl-2-butene is recommended. Toxic, suspected carcinogen [26] [31]. |

| 0.5 M Potassium Sulfate (Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Extracts solubilized organic carbon and nitrogen from fumigated and non-fumigated soils. | Standard extractant for FE; ratio is typically 1:4 (soil:extractant w/v) [26] [14]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Traps COâ‚‚ respired during the FI incubation for subsequent titration. | Used in a shallow vial inside the incubation jar with the soil sample [27]. |

| Chemical Fume Hood | Primary engineering control for all procedures involving chloroform. | Mandatory for protecting the researcher from toxic vapors [31]. |

The comparative analysis demonstrates a clear trade-off: while FI is a direct physiological measurement, FE offers greater speed, versatility, and applicability to a wider range of soil types.

Select Fumigation-Incubation (FI) if:

- Working with non-acidic, non-waterlogged soils where a physiological respiration-based measurement is preferred.

- Your laboratory infrastructure is geared towards respirometric measurements (e.g., GC, IRGA) but lacks access to a TOC analyzer.

Select Fumigation-Extraction (FE) if:

- Analyzing a broad range of soils, including acidic, waterlogged, or high organic matter soils [28] [29].

- Research requires high-throughput analysis or the simultaneous measurement of microbial biomass C, N, P, and S [26] [29].

- The study involves isotopic labeling with a wider range of isotopes (e.g., 32P, 35S) [27].

For most contemporary research scenarios, particularly those involving diverse soil types or high-throughput needs, the FE method presents the more robust and efficient choice, explaining its status as the current dominant technique in the field.

Method Workflows

Quantifying the soil microbial biomass is fundamental to understanding the role of microorganisms in driving biogeochemical processes, from organic matter decomposition to nutrient cycling [26]. This living component, often described as the "eye of the needle" through which all organic matter must pass, represents a small but critically active portion of soil organic matter [26]. Researchers have developed a suite of methodologies to estimate microbial biomass, each with distinct principles, advantages, and limitations. These methods can be broadly categorized into physiological approaches like substrate-induced respiration (SIR) and fumigation incubation (FI), chemical extraction techniques such as fumigation extraction (FE), and biochemical assays including measurements of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or specific cellular components like ergosterol [32] [26].

The choice of method is rarely arbitrary and is often dictated by the specific research question, soil properties, and practical constraints. While no single method is without limitations, the use of multiple, independent techniques in tandem provides a powerful strategy to validate findings and ensure robust interpretation of the data [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these key methods, with a particular focus on the role of Substrate-Induced Respiration and the derived metabolic quotients in physiological profiling of soil microbial communities.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Biomass Measurement Methods

Table 1: Comparison of major microbial biomass measurement methods.

| Method | Principle | What it Measures | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate-Induced Respiration (SIR) | Measures initial respiration response after adding an excess of an easily available substrate (e.g., glucose) [33]. | Maximum initial respiratory response, proportional to active microbial biomass [32]. | Simple, rapid, and cost-effective; can be combined with selective inhibition to estimate fungal:bacterial ratios [32]. | Does not measure total biomass C directly; requires calibration; response can be influenced by soil community structure [34]. |

| Fumigation-Extraction (FE) | Fumigation with chloroform lyses microbial cells; subsequent extraction measures released cellular components (e.g., C, N) [26]. | Extractable carbon (or nitrogen) from lysed microbial cells [34]. | Directly accesses a wide range of elements; dominant method in modern studies [26]. | Requires a calibration factor (kEC) to convert extracted C to biomass C; use of toxic chloroform [34] [26]. |

| Fumigation-Incubation (FI) | Fumigation lyses cells; subsequent incubation measures COâ‚‚ released from the decomposition of killed biomass by re-colonizers [26]. | COâ‚‚ flush from decomposition of lysed biomass. | Well-established historical method. | Requires an active, non-stressed re-colonizing population; unsuitable for soils with high organic matter or low pH [34]. |

| Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Assay | Extraction and measurement of ATP, a universal energy currency found in all living cells [26]. | Concentration of ATP in soil, correlated with microbial biomass [26] [35]. | Very rapid, sensitive, and cheap; particularly useful for soils with low organic matter [26]. | Requires a stable ATP-to-biomass-C ratio for conversion; this ratio can be affected by environmental conditions [26]. |

| Microscopy (Biovolume) | Direct counting and sizing of microbial cells (bacteria, fungal hyphae) in a soil film or smear [32]. | Direct count and biovolume of bacteria and fungi. | Direct observation of community structure; does not rely on physiological or chemical constants [32]. | Time-consuming and requires significant expertise; can be subjective [32]. |

Table 2: Summary of quantitative performance from comparative studies.

| Study Context | Method A | Method B | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soils with different pH (2.6 to 11.1% organic C) | Fumigation-Extraction (FE) | Substrate-Induced Respiration (SIR) | Strong correlation (r=0.95) between microbial biomass C estimates from both methods across the pH range. | [34] |

| Metal-contaminated soils | Fumigation-Extraction (FE) | SIR / ATP | Microbial biomass in metal-contaminated soils was about half of that in control soils, a result confirmed by all three methods (FE, SIR, ATP). | [35] |

| Ryegrass-amended & fumigated soils | Selective Inhibition (via SIR) | Direct Microscopy | Both methods detected the same directional shifts in fungal:bacterial ratios following soil treatments, demonstrating good agreement. | [32] |

| Various soils (15 studies) | ATP (Enzymatic assay) | FE (for MBC) | A weighted median of 9.6 µmol ATP gâ»Â¹ MBC was established, providing a conversion ratio. | [26] |

| Various soils (21 studies) | ATP (HPLC assay) | FE (for MBC) | A median of 5.8 µmol ATP gâ»Â¹ MBC was found, highlighting how methodology can influence conversion factors. | [26] |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Substrate-Induced Respiration (SIR) and Selective Inhibition

The Substrate-Induced Respiration (SIR) method is based on measuring the initial burst of respiration after adding an ample amount of an easily decomposable substrate, most commonly glucose, to the soil [33]. This maximum respiratory response is directly proportional to the size of the active microbial biomass. A key advantage of the SIR method is its adaptability for determining the community structure of the biomass through selective inhibition [32].

Experimental Protocol for SIR with Selective Inhibition:

- Soil Preparation: Sieve (<2 mm) field-moist soil and adjust moisture to approximately 40-50% of its water-holding capacity. Pre-incubate for a defined period (e.g., 5-10 days) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C) to stabilize microbial activity.

- Substrate Addition: Amend soil samples with a glucose solution to achieve a concentration that saturates microbial metabolism (a common rate is 5-10 mg glucose gâ»Â¹ soil). Include control samples without glucose.

- Selective Inhibition (for community structure): To parallel samples, add either a bacterial antibiotic (e.g., streptomycin) or a fungal antibiotic (e.g., cycloheximide) along with the glucose substrate.

- Respiratory Measurement: Immediately transfer the soils to sealed containers and incubate. Measure the evolution of COâ‚‚ over a short period (2-6 hours) using an infrared gas analyzer or by trapping COâ‚‚ in an alkali solution and titrating.

- Calculation:

- Total Microbial Biomass C: The maximum initial respiration rate (µL COâ‚‚ gâ»Â¹ soil hâ»Â¹) from the glucose-amended sample is calculated. This value can be converted to microbial biomass C using a calibration factor established in the literature.

- Fungal:Bacterial Ratios: The respiration inhibited by streptomycin is attributed to bacteria, while the respiration inhibited by cycloheximide is attributed to fungi. These values are used to estimate the proportional contributions of each group to the total biomass [32].

Fumigation-Extraction (FE) Method

The Fumigation-Extraction (FE) method is currently the dominant technique for estimating microbial biomass carbon (MBC) [26]. It involves lysing microbial cells with chloroform vapor and then extracting and quantifying the cellular components released into the soil.

Experimental Protocol for FE:

- Soil Preparation: Divide a moist soil sample (>40% water-holding capacity) into two subsamples.

- Fumigation: Place one subsample in a desiccator with ethanol-free chloroform (often stabilized with 2-methyl-2-butene) and fumigate for 24 hours in the dark. After fumigation, remove the chloroform by repeated evacuation.

- Extraction: Extract both the fumigated subsample and the non-fumigated control subsample with 0.5 M Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„ (typically at a 1:4 soil:extractant ratio) by oscillating shaking for 30 minutes. Filter the extracts.

- Analysis: Analyze the extracts for organic carbon (e.g., using a TOC analyzer). The difference in extractable organic C between the fumigated and non-fumigated samples represents the carbon flushed from the lysed microbial cells (CHCl₃-labile C).

- Calculation: Microbial biomass C (MBC) is calculated as: MBC = EC / kEC, where EC is (organic C from fumigated soil) - (organic C from non-fumigated soil), and kEC is an empirical conversion factor, typically ranging from 0.35 to 0.45 [26].

Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Assay

Measuring Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) offers a rapid and sensitive alternative for estimating microbial biomass, as ATP is the universal energy currency of living cells and is degraded rapidly in dead cells [26].

Experimental Protocol for ATP Analysis:

- Extraction: Add a potent extractant, such as trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or a proprietary buffer, to a soil sample to immediately inactivate enzymes and release ATP from microbial cells. Vigorously mix the suspension.

- Analysis: Two main analytical paths can be followed:

- Enzymatic Assay (Luminometry): Mix a portion of the soil extract with a firefly luciferin-luciferase enzyme complex. The light produced in the reaction, measured with a luminometer, is directly proportional to the ATP concentration. This method has been improved by replacing toxic paraquat with imidazole in the extractant [26].

- Chromatographic Assay (HPLC): Use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to separate and quantify ATP along with other adenylates (ADP, AMP). This allows for the calculation of the Adenylate Energy Charge (AEC), an indicator of the metabolic energy status of the microbial community [26].

- Calculation: The measured ATP concentration is converted to microbial biomass C using a published ratio. Recent reviews suggest a median of 9.6 µmol ATP gâ»Â¹ MBC for the enzymatic assay and 5.8 µmol ATP gâ»Â¹ MBC for the HPLC-based technique [26].

Workflow and Metabolic Profiling

Experimental Workflow for Method Selection and Comparison

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making workflow for selecting and applying the primary microbial biomass measurement methods discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting microbial biomass measurement methods to achieve physiological profiling.

Calculation and Interpretation of Metabolic Quotients

Physiological profiling extends beyond mere biomass quantification to assess the metabolic state of the soil microbial community. This is achieved by calculating specific metabolic quotients.

Metabolic Quotient (qCOâ‚‚): The metabolic quotient for COâ‚‚ (qCOâ‚‚) is the rate of basal respiration per unit of microbial biomass [34]. It represents the maintenance energy requirement of the soil microbial community and is interpreted as an indicator of environmental stress or ecosystem development. A higher qCOâ‚‚ suggests a microbial community under stress (e.g., from metal contamination, low pH) or in a state of ecological succession, where energy is inefficiently used for maintenance rather than growth [34].

Adenylate Energy Charge (AEC): The Adenylate Energy Charge is calculated when ATP, ADP, and AMP are measured (typically via HPLC) using the formula: AEC = (ATP + 0.5 × ADP) / (ATP + ADP + AMP) [26]. This ratio, which can range from 0 (all AMP) to 1 (all ATP), reflects the energy status of the microbial cells. A high AEC (>0.8) indicates a metabolically active and healthy community, while a low AEC suggests a starved or stressed community [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for microbial biomass measurements.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Glucose | The standard substrate used in the SIR method to induce a maximum respiratory response from the soil microbial community [33]. |

| Streptomycin & Cycloheximide | Antibiotics used in the selective inhibition technique, applied during SIR to selectively suppress bacterial and fungal activity, respectively, allowing for the estimation of their biomass contributions [32]. |

| Ethanol-free Chloroform | The fumigant used in FE and FI methods to lyse microbial cells. It is often stabilized with 2-methyl-2-butene (β-isoamylene) to avoid the complications of ethanol-stabilized chloroform and to facilitate its complete removal from soil [26]. |

| 0.5 M Potassium Sulfate (Kâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | The common extractant solution used in the FE method to dissolve cellular components released from fumigated microbial biomass [34] [26]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) / Imidazole | A powerful extractant combination used for the efficient and rapid extraction of ATP from soil microorganisms, with imidazole acting as a safer replacement for toxic paraquat [26]. |

| Luciferin-Luciferase Enzyme Complex | The key reagent in the bioluminescent ATP assay. It reacts with ATP to produce light, the intensity of which is measured with a luminometer to quantify ATP concentration [26]. |

| COâ‚‚ Trapping Solution (e.g., NaOH) | Used in respirometric methods (SIR, FI) to absorb evolved COâ‚‚, which is later quantified by titration to determine the rate of microbial respiration [32]. |

| Infrared Gas Analyzer (IRGA) | An instrumental alternative to chemical trapping for the direct, real-time measurement of COâ‚‚ concentration in the headspace of incubating soil samples, used in SIR and other respiration methods [36]. |

| Antifungal agent 44 | Antifungal agent 44, MF:C41H51BrNO4P, MW:732.7 g/mol |

| TDI-015051 | TDI-015051, MF:C22H22FN5O4S, MW:471.5 g/mol |

The accurate quantification of microbial biomass is a fundamental requirement in diverse fields, including environmental science, pharmacology, and soil health research. Among the various techniques available, the analysis of Phospholipid Fatty Acids (PLFA) and Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) has emerged as two prominent culturing-independent methods for estimating viable microbial biomass and, to a limited extent, assessing community composition. These biomarkers offer a rapid snapshot of the living microbial component, as they are rapidly degraded upon cell death. This guide provides a objective comparison of PLFA and ATP analysis, detailing their principles, experimental protocols, and performance characteristics to aid researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for their specific applications.

Principles and Methodological Comparison

PLFA analysis is a phenotypic approach that exploits the structural diversity of phospholipids, which are essential components of the cell membranes of all living organisms [37]. The method is based on the premise that phospholipids are rapidly degraded upon cell death, and thus provide a measure of the viable microbial community [37]. The profile of different PLFAs can serve as a fingerprint of the microbial community structure, and specific "signature" PLFAs can indicate the presence of broad microbial groups, such as fungi, Gram-positive bacteria, and Gram-negative bacteria [37].

ATP analysis, in contrast, quantifies adenosine triphosphate, the universal energy currency of all living cells [26]. Its concentration in a sample is used as a direct indicator of the presence of metabolically active biomass. The assay is fast, robust, and easy to perform [38]. A stable ratio of ATP to Microbial Biomass Carbon (MBC) is often assumed, allowing for the estimation of total living biomass from ATP measurements [26].

Table 1: Core Principles of PLFA and ATP Analyses

| Feature | Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) | Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Phospholipids from cell membranes [37] | Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from cells [26] |

| Fundamental Principle | Phenotypic; membrane structural diversity [37] | Physiological; universal energy currency [26] |

| Information Gained | Total viable biomass; coarse-level community structure [37] | Total metabolically active biomass |

| Key Assumption | Phospholipids degrade rapidly after cell death [37] | ATP concentration correlates linearly with biomass [26] |

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key procedural steps for each method.

PLFA Analysis Workflow

ATP Analysis Workflow

Comparative Performance Data

The performance of PLFA and ATP can be evaluated based on their sensitivity, the quantitative data they yield, and their ability to reflect changes in microbial communities under different conditions.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of PLFA and ATP in Environmental Samples

| Performance Metric | PLFA Analysis | ATP Analysis | Context & Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Biomass Yield | 1.17 × 10⹠± 7.68 × 10⸠cells gâ»Â¹ dry soil (converted from PLFA) [38] | 9.47 × 10⸠± 1.07 × 10â¹ cells gâ»Â¹ dry soil (converted from ATP) [38] | Comparison in grassland soils showed PLFA and ATP yielded comparable but variable cell counts [38]. |

| Sensitivity to Management | Detects changes under no-till vs. conventional tillage; organic vs. conventional farming [12]. | Rapid response to environmental changes; useful for long-term monitoring [12]. | Both are sensitive indicators, but PLFA provides additional structural information [12]. |

| Community Composition Insight | Can distinguish broad groups (e.g., fungi, G+ and G- bacteria) using specific biomarkers [37]. | No taxonomic information; reflects total metabolically active biomass only. | PLFA profiles revealed 7 to 15 different individual PLFAs across a precipitation gradient [39]. |

| Correlation with Other Methods | Significantly different view of bacterial composition compared to 16S rRNA metabarcoding [40]. | Good correlation with FCM and PLFA for total biomass estimation in some studies [38]. | In a multi-method comparison, PLFA, ATP, FCM, and qPCR showed varying degrees of agreement [38]. |

A critical application of these methods is their use in conjunction with molecular techniques like 16S rRNA gene metabarcoding. While metabarcoding reveals relative taxonomic abundances, it cannot provide absolute quantitative data. PLFA analysis can be used to "calibrate" these relative sequences abundances into estimated absolute abundances, providing a more accurate picture of the microbial community [40]. For instance, one study found that adjusting relative abundances from metabarcoding with PLFA-based biomass estimates led to significant changes in the perceived microbial community composition across all substrates tested [40].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) Analysis

The following protocol is adapted from established methods [37] [41] and is routinely used for soil and environmental samples.

Lipid Extraction:

- Weigh 2-3 g of freeze-dried and homogenized sample.

- Add a single-phase extraction mixture consisting of chloroform, methanol, and a citrate buffer (pH 4.0) or phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a ratio of 1:2:0.8 (Bligh & Dyer method). The choice of buffer can affect efficiency, with citrate sometimes yielding more from acidic, organic-rich soils [41].

- Shake vigorously for 2 hours and centrifuge to separate phases. The organic (chloroform) layer contains the total lipids.

Lipid Fractionation:

- Load the concentrated lipid extract onto a solid-phase extraction (SPE) column packed with silica gel.

- Sequentially elute with:

- Chloroform → Recovers neutral lipids (e.g., triglycerides, cholesterol esters).

- Acetone → Recovers glycolipids.

- Methanol → Recovers the target phospholipids.

- Note: Recent efficiency evaluations suggest methanol may fail to recover a majority of phospholipids yet elute unexpected glycolipid, potentially biasing results [41]. This step requires careful validation.

Mild Alkaline Methanolysis (Transesterification):

- Take the methanol fraction (containing phospholipids) to dryness under a stream of Nâ‚‚ gas.

- Add a solution of methanol-toluene and a KOH solution (alkaline catalyst) to convert the phospholipid fatty acids into Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs).

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes. The alkaline catalyst is generally more efficient (mean 86% across phospholipids) than an acidic one [41].

Analysis by Gas Chromatography (GC):

- Re-dissolve the FAMEs in hexane and inject into a Gas Chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) or a mass spectrometer (MS).

- Identify individual FAMEs by comparing their retention times to known standards. Quantify based on peak areas.

Protocol for Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Analysis

This protocol is based on the enzymatic luciferin-luciferase reaction and can be applied to soil and other biological samples [26].

ATP Extraction:

- Weigh 1 g of fresh soil/sample.