Advanced Methods for Analyzing Microbial Community Dynamics: From Sequencing to Predictive Modeling

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary methods for analyzing microbial community dynamics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced Methods for Analyzing Microbial Community Dynamics: From Sequencing to Predictive Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary methods for analyzing microbial community dynamics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of microbial interactions and the pivotal role of dynamics in ecosystems ranging from the human gut to wastewater treatment. The piece delves into cutting-edge methodological applications, including high-throughput sequencing, quantitative profiling, and graph neural networks for temporal forecasting. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for model reconstruction and data integration. Finally, it offers a rigorous comparative analysis of method validation, benchmarking the performance of various tools and approaches. This synthesis aims to serve as a guide for selecting and implementing robust analytical frameworks in both research and clinical development.

The Core Principles of Microbial Communities and Their Dynamics

Application Note: Deciphering Microbial Cross-Talk through Modern Methodologies

Microbial interactions function as fundamental units in complex ecosystems, driving community structure, stability, and function [1]. These interactions—classified as positive (mutualism, commensalism), negative (competition, amensalism, parasitism), or neutral—govern ecosystem processes ranging from biogeochemical cycling in soils to host-microbe relationships in human health [2] [1]. Understanding the precise mechanisms of these dynamic exchanges, particularly quorum sensing and metabolic cross-feeding, provides crucial insights for manipulating microbial communities to address pressing challenges in agriculture, medicine, and environmental biotechnology.

Recent technological advances have transformed our ability to probe these interactions from qualitative observations to quantitative, predictive frameworks. This Application Note synthesizes current methodologies and presents a detailed protocol for investigating a specific case of quorum sensing-mediated metabolic cross-feeding that enhances aluminum tolerance in soil microbial consortia, demonstrating the practical application of these techniques in a real-world research context [3] [4].

Key Experimental Findings: Quinolone-Mediated Cross-Feeding

A recent investigation revealed a sophisticated metabolic cross-feeding mechanism between Rhodococcus erythropolis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa that confers enhanced aluminum tolerance to the consortium [3] [4]. The study demonstrated that:

- Co-culture consortium (RP) exhibited significantly greater Al tolerance than either bacterium in mono-culture, with enhanced metabolic activity under Al stress measured via single-cell Raman spectroscopy with reverse heavy water labeling (Reverse-Raman-D2O) [3].

- P. aeruginosa produces the quorum sensing molecule 2-heptyl-1H-quinolin-4-one (HHQ), which is efficiently degraded by R. erythropolis [3].

- This degradation reduces quorum sensing-mediated population density limitations, further enhancing the metabolic activity of P. aeruginosa under Al stress [3].

- R. erythropolis converts HHQ into tryptophan via the chorismate biosynthesis pathway, promoting peptidoglycan synthesis for improved cell wall stability and enhanced Al tolerance [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Data from Bacterial Co-culture Under Aluminum Stress

| Parameter | Mono-culture | Co-culture | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa metabolic activity (1.0 mM Al³âº) | Unchanged from baseline | Significantly augmented | Reverse-Raman-D2O (C-D ratio) |

| R. erythropolis metabolic activity (1.0 mM Al³âº) | Decreased by 28.46% | Increased by 25.42% | Reverse-Raman-D2O (C-D ratio) |

| P. aeruginosa cell density (12h, 0.1 mM Al³âº) | 5.72 × 10â¹ copies mLâ»Â¹ | 1.53x greater than mono-culture | Growth curve analysis |

| HHQ concentration | High in P. aeruginosa mono-culture | Reduced by ~50% | GC-MS |

| Plant growth promotion (Shoot fresh weight) | Increased with mono-culture | 21.32-34.98% greater than mono-cultures | Field measurement |

Protocol: Analyzing Quorum Sensing-Mediated Metabolic Cross-Feeding

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for investigating the quinolone-mediated metabolic cross-feeding mechanism:

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | Model organisms for interaction studies | Rhodococcus erythropolis & Pseudomonas aeruginosa [3] |

| Minimal Media | Cultivation under controlled nutrient conditions | pH 4.0 with varying Al³⺠concentrations (0-1.0 mM) [3] |

| Heavy Water (Dâ‚‚O) | Labeling for metabolic activity assessment | Reverse-Raman-D2O spectroscopy [3] |

| GC-MS Equipment | Detection and quantification of metabolites | Identification of HHQ and other cross-fed metabolites [3] |

| FISH Probes | Visualization and quantification of colonization | Species-specific 16S rRNA probes [3] |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Quantification of absolute bacterial abundance | Species-specific primers [3] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Phase 1: Cultivation and Growth Assessment

- Culture Preparation: Maintain Rhodococcus erythropolis (Rh) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Ps) as pure cultures. Prepare co-culture (RP) by combining equal cell numbers.

- Aluminum Stress Application: Inoculate mono-cultures and co-culture in minimal medium (pH 4.0) supplemented with Al³⺠(0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 mM). Use unsupplemented medium as control.

- Growth Monitoring: Measure optical density (OD₆₀₀) and perform quantitative culture for 24-48 hours to establish growth curves and determine cell densities (copies mLâ»Â¹).

- Metabolic Activity Assessment:

- Add 20% Dâ‚‚O (v/v) to cultures under Al stress.

- Incubate for 6-12 hours.

- Measure C-D ratio using single-cell Raman spectroscopy.

- Calculate metabolic activity based on deuterium incorporation (lower C-D ratio indicates higher activity).

Phase 2: Molecular Analysis of Cross-Feeding

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis:

- Culture bacteria in Al-supplemented medium for 24 hours.

- Centrifuge cultures (10,000 × g, 10 min) to separate cells from supernatant.

- Extract metabolites from supernatant using ethyl acetate.

- Analyze extracts by GC-MS for HHQ and other metabolites.

- Compare metabolite profiles between mono-cultures and co-culture.

Molecular Docking Simulations:

- Obtain 3D structures of QsdR and mvfR transcription factors from protein databases.

- Prepare HHQ and other detected metabolite structures.

- Perform semiflexible molecular docking to calculate binding free energies.

- Identify metabolites with strongest binding affinities.

Phase 3: Functional Validation

Colonization Efficiency:

- Extract metagenomic DNA from culture samples.

- Perform qRT-PCR with species-specific primers to determine absolute abundance of each strain.

- Compare abundance in mono-culture versus co-culture.

Plant Bioassays:

- Inoculate rice plants with mono-cultures or co-culture under acidic soil conditions with Al toxicity.

- Measure plant growth parameters (shoot fresh weight, root length, grain yield) after 60-90 days.

- Determine Al content in plant tissues.

Expected Results and Interpretation

- Successful cross-feeding is indicated by reduced HHQ in co-culture versus P. aeruginosa mono-culture, enhanced metabolic activity of both partners in co-culture under Al stress, and improved plant growth with co-culture inoculation.

- Molecular mechanism validation requires demonstration of strong binding affinity between HHQ and regulatory proteins, plus conversion of HHQ to tryptophan in R. erythropolis.

- Technical considerations: Include appropriate controls (uninoculated media, pure cultures), perform experiments with biological replicates (n≥3), and use standardized culture conditions.

Advanced Analytical Methods for Microbial Interaction Research

Computational Modeling of Community Dynamics

Graph neural network (GNN) models represent advanced computational tools for predicting microbial community dynamics based on historical abundance data [5]. The "mc-prediction" workflow uses only historical relative abundance data to predict future species dynamics, accurately forecasting up to 10 time points ahead (2-4 months) in wastewater treatment plant microbiota [5].

Table 3: Comparison of Microbial Interaction Analysis Methods

| Method Type | Examples | Key Applications | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Co-culturing, Microscopy, Metabolite profiling | Observation of directionality, mode of action, spatiotemporal variation [1] | Species to Community |

| Quantitative | Network inference, GNN models, Synthetic consortia | Prediction of dynamics, Hypothesis testing, Community design [5] [1] | Strain to Ecosystem |

| Multi-omics | Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics, Metaproteomics | Functional potential, Active processes, Biomolecular activity [6] | Gene to Pathway |

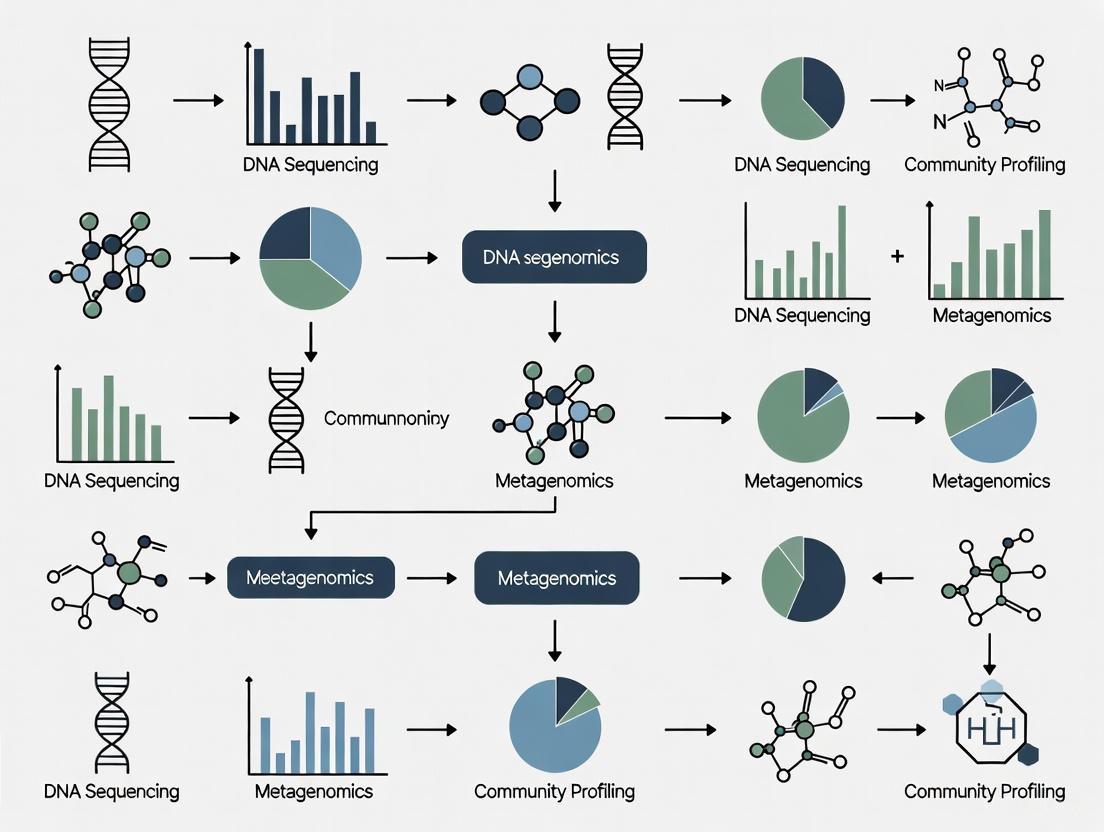

Multi-omics Integration Framework

The following diagram illustrates the integration of multi-omics data for comprehensive analysis of microbial interactions:

Strain-Level Resolution in Microbial Epidemiology

Strain-level differentiation is crucial for understanding microbial interactions as functional capabilities can vary dramatically within species [6]. For example, Escherichia coli encompasses neutral commensals, pathogens, and probiotic strains within its pangenome of over 16,000 genes [6]. Strain resolution can be achieved through:

- Shotgun metagenomics with single nucleotide variant (SNV) calling or variable region identification

- Advanced 16S analysis discriminating sequence variants differing by just single nucleotides

- Culture-based methods complemented by molecular typing

This resolution is particularly important when linking microbial interactions to functional outcomes, as strain-specific genes often determine interactions and ecological impacts [6].

The integration of qualitative observations, quantitative measurements, and computational modeling provides a powerful framework for deciphering complex microbial interactions. The protocol presented here for analyzing quorum sensing-mediated metabolic cross-feeding exemplifies how modern methodologies can unravel sophisticated microbial dialogue with important implications for managing microbial communities in agricultural, environmental, and biomedical contexts. As these methods continue to evolve, particularly with advances in multi-omics integration and machine learning, researchers will gain increasingly predictive understanding of microbial community dynamics, enabling the rational design of microbial consortia for specific applications.

Understanding temporal dynamics is fundamental to microbial ecology, influencing outcomes from ecosystem stability in wastewater treatment to host health in mammals. Microbial communities are not static; their composition and function fluctuate due to a complex interplay of deterministic forces (like environmental selection) and stochastic events (like ecological drift) [7]. These temporal shifts can dictate the functional output of an ecosystem, affecting processes from pollutant removal in engineered systems to immune modulation in hosts. Analyzing these dynamics requires robust methodological frameworks capable of capturing and predicting complex, multi-variable interactions over time. This application note details cutting-edge protocols and analytical tools for capturing and interpreting microbial temporal dynamics, providing researchers with a practical toolkit for advanced community ecology research.

Application Notes: Core Concepts and Current Research

The Ecological Foundations of Microbial Dynamics

The assembly and maintenance of microbial communities over time are governed by core ecological processes, often framed by the dichotomy between niche-based and neutral theories [7].

- Deterministic vs. Stochastic Processes: Deterministic processes are directional forces that shape community structure predictably, driven by factors like environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH), host filtering (e.g., immune pressure), and specific species traits. In contrast, stochastic processes are random events—such as unpredictable dispersal, birth, or death—that cause non-directional variation in species abundance [7].

- Priority Effects: The timing and order of species arrival during community assembly can have lasting effects on the community's trajectory. Early colonizers can shape subsequent dynamics through:

- Niche Preemption: Consuming resources to limit the success of late-arriving species.

- Niche Modification: Altering the environment to facilitate later colonizers [7].

- Disruptions to the expected order of succession in the human infant gut, for instance, have been linked to various disease states [7].

Predictive Modeling of Temporal Dynamics

A landmark 2025 study demonstrated the power of machine learning for forecasting microbial community dynamics. The research developed a graph neural network (GNN) model to predict species-level abundance in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) up to 2-4 months into the future, using only historical relative abundance data [5].

- Key Innovation: The GNN architecture is uniquely suited for this task as it learns the relational dependencies and interaction strengths between different microbial taxa, represented as a graph, while simultaneously extracting temporal features from the time-series data [5].

- Performance: The model, implemented as the "mc-prediction" workflow, was validated on 24 full-scale WWTPs (4,709 samples over 3-8 years) and was also successfully applied to human gut microbiome datasets, confirming its broad applicability to any longitudinal microbial system [5].

Case Study: Seasonal vs. Crop-Driven Dynamics in Soil

A 2025 study on rotational cropping systems highlights the relative impact of different temporal drivers. The research found that while crop species and growth stages influenced soil microbial community structure, these effects were generally modest and variable. In contrast, seasonal factors and soil physicochemical properties—particularly electrical conductivity—exerted stronger and more consistent effects on microbial beta diversity [8]. Despite taxonomic shifts, a core microbiome dominated by Acidobacteriota and Bacillus persisted across seasons, and functional predictions revealed an environmentally controlled peak in nitrification potential during warmer months [8]. This underscores the resilience of soil microbiomes and the dominant role of abiotic temporal factors in this system.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Predicting Microbial Dynamics with Graph Neural Networks

This protocol summarizes the methodology for implementing the GNN-based prediction model as described in Skytte et al. Nat Commun (2025) [5].

1. Sample Collection and Data Generation

- Objective: Obtain longitudinal relative abundance data for a microbial community.

- Procedure:

- Collect time-series samples from the ecosystem of interest (e.g., activated sludge, host gut, soil). The Danish WWTP study collected 4,709 samples over 3-8 years, at a frequency of 2-5 times per month [5].

- Perform DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (e.g., targeting the V3-V4 region) on all samples.

- Process sequences using a standard pipeline (e.g., DADA2) to infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and classify taxa using an appropriate reference database (e.g., MiDAS 4 for wastewater) [5].

- Generate a relative abundance table for the top ~200 ASVs, which typically captures >50% of the community biomass.

2. Data Preprocessing and Clustering

- Objective: Structure the data for model input.

- Procedure:

- Make a chronological 3-way split of each time-series dataset into training, validation, and test sets [5].

- To maximize prediction accuracy, pre-cluster ASVs into small multivariate groups. The study found that clustering by graph network interaction strengths or by ranked abundances yielded the best results [5].

- Set the cluster size to 5 ASVs. Avoid clustering solely by broad biological function, as this reduced accuracy [5].

- Structure the data into moving windows of 10 consecutive historical time points as model inputs, with the goal of predicting the next 10 consecutive future time points.

3. Model Training and Prediction

- Objective: Train the GNN model to forecast future abundances.

- Procedure:

- Graph Convolution Layer: The model first learns the interaction strengths and extracts relational features between ASVs within each cluster [5].

- Temporal Convolution Layer: This layer then extracts temporal features across the 10-time-point window [5].

- Output Layer: Fully connected neural networks use the extracted relational and temporal features to predict the relative abundances of each ASV for the next 10 time points [5].

- Iterate this process throughout the training, validation, and test datasets. The model is designed to be trained and tested independently for each unique site or system.

Protocol: Assessing Soil Microbial Community Dynamics

This protocol is adapted from the rotational cropping study to analyze temporal dynamics in soil [8].

1. Field Design and Sampling

- Objective: Capture the effects of crop rotation and seasonality.

- Procedure:

- Establish a long-term crop rotation system. The cited study used a 6-year rotation cycle divided into six sectors [8].

- Collect bulk soil samples (e.g., from 0-20 cm depth) from each sector at multiple time points covering key seasonal changes and crop growth stages (e.g., pre-cultivation, peak growth, post-harvest). Use a minimum of four biological replicates per sector per time point [8].

- Pool and homogenize soil cores from each sampling point to minimize micro-variability.

2. Molecular and Physicochemical Analysis

- Objective: Generate community and environmental data.

- Procedure:

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Extract metagenomic DNA from all samples using a dedicated kit (e.g., FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil). Amplify the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4 region with primers Pro341F/Pro805R) and sequence on an Illumina platform [8].

- Bioinformatics: Process raw sequences through a standard pipeline (e.g., DADA2 in R) to infer ASVs. Assign taxonomy using a reference database (e.g., SILVA 138) [8].

- Soil Physicochemistry: Air-dry and sieve soils. Measure key variables like pH and electrical conductivity (EC) in a soil-water suspension. Perform Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy on supernatants to characterize organic components [8].

3. Data Integration and Statistical Analysis

- Objective: Identify drivers of temporal change.

- Procedure:

- Calculate alpha diversity (e.g., Shannon index, Chao1 richness) and beta diversity (e.g., Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) indices using packages like

Veganin R [8]. - Use non-parametric statistical tests (e.g., PERMANOVA) to relate community composition differences (beta diversity) to factors like crop type, sampling date, and soil properties like EC [8].

- Employ functional prediction tools (e.g., PICRUSt2) to infer metabolic potential and its changes over time.

- Calculate alpha diversity (e.g., Shannon index, Chao1 richness) and beta diversity (e.g., Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) indices using packages like

Data Visualization and Workflows

Workflow Diagram: Predictive Modeling of Microbial Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for collecting data and applying a graph neural network to predict microbial community dynamics.

Table 1: Summary of Predictive Model Performance Across Different Pre-clustering Methods [5] This table compares the prediction accuracy, measured by the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between predicted and actual communities, achieved using different methods for pre-clustering Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) before model training. Lower values indicate better performance.

| Pre-clustering Method | Brief Description | Median Prediction Accuracy (Bray-Curtis) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Network | Clusters ASVs based on interaction strengths learned by the GNN. | Best Overall | Captures complex, data-driven relational dependencies. |

| Ranked Abundance | Clusters ASVs in simple groups of 5 based on abundance ranking. | Very Good | Simple to implement, requires no prior biological knowledge. |

| IDEC Algorithm | Uses Improved Deep Embedded Clustering to self-determine clusters. | Good (High Variability) | Can achieve high accuracy but results are less consistent. |

| Biological Function | Clusters ASVs into groups like PAOs, NOBs, filamentous bacteria. | Lower | Intuitive, but generally resulted in lower prediction accuracy. |

Table 2: Key Abiotic and Temporal Drivers of Soil Microbial Community Dynamics [8] This table summarizes the relative influence of different factors on soil microbial community structure (beta diversity) as identified in the rotational cropping study.

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Strength of Influence on Community | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seasonal & Abiotic | Electrical Conductivity (EC) | Strong & Consistent | A key measure of soil salinity and ion content. |

| Seasonal & Abiotic | Seasonal Timing / Temperature | Strong & Consistent | Warm seasons showed a peak in predicted nitrification potential. |

| Biotic & Management | Crop Species / Identity | Modest & Variable | Effect was detectable but often outweighed by abiotic factors. |

| Biotic & Management | Crop Growth Stage | Modest & Variable | - |

| Community Property | Core Microbiome (e.g., Acidobacteriota, Bacillus) | Persistent | Dominant taxa remained stable across crops and seasons. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Dynamics Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) | Standardized and efficient metagenomic DNA extraction from complex environmental samples like soil and sludge [8]. |

| Pro341F / Pro805R Primers | PCR amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 hypervariable region for metabarcoding studies [8]. |

| Illumina MiSeq Platform | High-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA amplicons to profile microbial community composition [8]. |

| MiDAS 4 Database | Ecosystem-specific taxonomic reference database for high-resolution classification of ASVs from wastewater treatment ecosystems [5]. |

| SILVA SSU Database | Comprehensive, curated ribosomal RNA database for general taxonomic classification of 16S sequences from diverse environments [8]. |

| DADA2 (R package) | Pipeline for processing sequencing data to resolve exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), providing higher resolution than OTU clustering [8]. |

| "mc-prediction" Workflow | A publicly available software workflow (https://github.com/kasperskytte/mc-prediction) for implementing the graph neural network-based prediction model [5]. |

| Pyridin-4-ol | 4-Hydroxypyridine | High-Purity Reagent | RUO |

| 1-Boc-3-(hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidine | 1-Boc-3-(hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidine, CAS:114214-69-6, MF:C10H19NO3, MW:201.26 g/mol |

Application Note: Comparative Analysis of Microbial Community Dynamics

Microbial communities drive essential functions across diverse ecosystems, from human health to environmental processes. Understanding their dynamics in key habitats—the human gut, soil, and engineered systems—provides crucial insights for advancing medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology. This application note presents a standardized framework for comparing microbial community structure, function, and dynamics across these ecosystems, enabling researchers to identify universal principles and system-specific characteristics. We integrate quantitative comparisons, experimental protocols, and computational tools to support cross-disciplinary microbiome research.

Comparative Ecosystem Analysis

The table below summarizes key quantitative and functional characteristics of microbial communities across the three focal ecosystems, highlighting both shared and distinct properties.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microbial Communities in Key Ecosystems

| Parameter | Human Gut | Soil | Engineered Systems (WWTP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Density | 10^11-10^12 cells/g (colon) [9] | 10^7-10^9 cells/g [9] | Varies with operational parameters |

| Species Diversity | ~400-5000 species/g [9] | ~4,000-50,000 species/g [9] | Highly variable; often dominated by functional guilds |

| Core Functions | Nutrient metabolism, immune modulation, gut barrier integrity [10] | Biogeochemical cycling, organic matter decomposition, plant symbiosis [10] | Pollutant removal, nutrient recovery, sludge settling [5] |

| Key Specialist Taxa | Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Christensenella minuta [10] | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, N2-fixing rhizobia, methanotrophs [10] | Nitrosomonadaceae (AOB), Nitrospiraceae (NOB), Candidatus Microthrix [5] [11] |

| Key Generalist Taxa | Clostridium, Acinetobacter, Stenotrophomonas, Ruminococcus [10] | Clostridium, Acinetobacter, Stenotrophomonas, Pseudomonas [10] | Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas [10] [5] |

| Primary Dynamics Drivers | Diet, host genetics, medications, lifestyle [9] | Land use, plant cover, agricultural practices, climate [9] | Temperature, substrate loading, retention times, immigration [5] |

| Typical Disturbance Regimes | Antibiotics, dietary shifts, disease states | Crop rotation, tillage, chemical amendments [9] | Process upsets, toxic shocks, cleaning cycles (e.g., scraping in SSFs) [11] |

Conceptual Framework: The Microbiome Continuum

A significant paradigm in microbial ecology is the concept of interconnected microbiomes forming a continuum across different habitats. The soil-plant-human gut microbiome axis proposes that soil acts as a microbial seed bank, with microorganisms traversing to the human gut via plant-based food or direct environmental exposure [10]. This transmission has profound implications for human health, as geographic patterns in gut microbiome composition are influenced by local diet, lifestyle, and environmental exposure [10] [9]. Conversely, human activities reciprocally influence soil and engineered systems through waste streams and agricultural practices, creating a complex feedback loop [10] [9]. Engineered systems like wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) represent a critical node in this cycle, receiving and processing microbial communities from human populations [5].

Protocols for Microbial Community Analysis

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Sampling and Community Profiling

Objective: To collect and process temporal samples from human gut, soil, or engineered systems for microbial community analysis.

Materials:

- Sample Collection: Stool collection kits (gut), soil corers (soil), automated water samplers or grab bottles (engineered systems).

- Preservation: RNAlater, DNA/RNA Shield, or immediate freezing at -80°C.

- DNA Extraction: Kits optimized for difficult matrices (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit).

- Library Prep & Sequencing: 16S rRNA gene primers (e.g., 515F/806R for V4 region), metagenomic shotgun sequencing kits.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection:

- Human Gut: Collect fecal samples using standardized kits. Record participant metadata (diet, health status).

- Soil: Use a sterile corer to collect rhizosphere or bulk soil from multiple points in a transect. Combine and homogenize.

- Engineered Systems: Collect biomass (e.g., activated sludge, Schmutzdecke layer from slow sand filters) in triplicate at consistent time intervals (e.g., 2-5 times per month) [5] [11].

- Preservation: Immediately preserve samples according to the chosen reagent's protocol. Store at -80°C until nucleic acid extraction.

- DNA Extraction: Follow manufacturer's protocols with included bead-beating step for mechanical lysis. Include extraction blanks as controls.

- Sequencing Library Preparation:

- For 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, amplify the target region using barcoded primers.

- For metagenomic shotgun sequencing, fragment DNA and construct libraries using a commercial kit.

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq for 16S, NovaSeq for metagenomes).

Protocol 2: Computational Analysis of Temporal Dynamics

Objective: To process sequencing data and model the temporal dynamics of microbial communities.

Materials:

- Computing Infrastructure: High-performance computing cluster or workstation with sufficient RAM (>32 GB recommended).

- Software: QIIME 2, DADA2, Mc-Prediction workflow [5], R or Python with relevant packages (phyloseq, microbiome, scikit-learn).

Procedure:

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- 16S Data: Demultiplex sequences, perform quality filtering, denoising (e.g., with DADA2), and Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) classification against a reference database (e.g., MiDAS for WWTPs [5], SILVA for general use).

- Shotgun Metagenomic Data: Perform quality trimming, remove host/environmental reads, and assemble contigs or directly analyze with tools like HUMAnN3 for functional profiling.

- Community Metrics Calculation: Calculate alpha-diversity (e.g., Chao1, Shannon) and beta-diversity (e.g., Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) indices.

- Temporal Modeling with Graph Neural Networks (GNN):

- Input: A time-series of relative abundance data for the top ~200 ASVs/species.

- Pre-clustering: Cluster ASVs into groups (e.g., of 5) based on graph network interaction strengths to improve prediction accuracy [5].

- Model Training: Train the GNN model on chronological training data using moving windows of 10 consecutive time points.

- Prediction: Use the trained model (

mc-predictionworkflow) to predict future community composition (e.g., up to 10 time points ahead) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents, tools, and computational resources for conducting microbial community dynamics research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Microbial Community Dynamics

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | High-efficiency DNA extraction from difficult samples with inhibitors (soil, stool). | Standardized DNA extraction for cross-study comparison of soil and gut microbiomes. |

| MiDAS 4 Database | Ecosystem-specific 16S rRNA reference database for accurate taxonomic classification in wastewater. | Identifying process-critical bacteria like Nitrospiraceae (NOB) in activated sludge [5]. |

| Mc-Prediction Workflow | Graph neural network-based tool for predicting future microbial community structure from time-series data. | Forecasting dynamics of functional guilds in a WWTP 2-4 months in advance [5]. |

| RNAlater / DNA/RNA Shield | Preserves nucleic acid integrity in samples during storage and transport. | Stabilizing microbial community structure in field-collected soil or water samples. |

| Viz Palette Tool | Online tool to test and adjust color palettes for accessibility (color blindness). | Ensuring scientific figures are interpretable by all readers [12]. |

| ggsci R Package Palettes | Provides color palettes inspired by scientific journals (e.g., 'nejm', 'lancet'). | Creating publication-ready, color-blind safe figures for microbial community bar plots [13]. |

| Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle | Iterative engineering framework for manipulating and optimizing microbiome function. | Engineering a synthetic community for enhanced pollutant degradation in a bioreactor [14]. |

| 1,2-Didecanoyl PC | 1,2-Didecanoyl PC, CAS:3436-44-0, MF:C28H56NO8P, MW:565.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 9-Anthryldiazomethane | 9-Anthryldiazomethane | Derivatization Reagent | 9-Anthryldiazomethane is a fluorescent derivatization agent for HPLC analysis of carboxylic acids. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Case Studies in Dynamics and Engineering

Case Study 1: Predictive Management in Wastewater Treatment

In a longitudinal study of 24 Danish wastewater treatment plants, a graph neural network model was trained on historical relative abundance data of the top 200 Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). The model successfully predicted species-level dynamics up to 2-4 months into the future, enabling proactive management of process-critical microbes like the filamentous Candidatus Microthrix, which can cause sludge settling problems [5]. This demonstrates the power of predictive models for maintaining stability in engineered ecosystems.

Case Study 2: Dysbiosis in the Konjac Rhizosphere

Metagenomic analysis of the konjac rhizosphere during soft rot disease revealed significant shifts in microbial community structure. A notable peak in microbial richness (Chao1 index) was observed in diseased plants, a phenomenon known as dysbiosis-associated richness inflation. Furthermore, the diseased state was characterized by a significant enrichment of pathogenic Rhizopus species and a decline in putative beneficial taxa like Chloroflexi and Acidobacteria [15]. This highlights how cross-kingdom interactions (plant-microbe) drive dynamics in soil ecosystems.

The DBTL Framework for Microbiome Engineering

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle provides a systematic approach for engineering microbiomes [14]. This iterative process can be applied across ecosystems:

- Design: Formulate a microbiome configuration for a desired function. This can be top-down (using environmental variables like substrate loading to shape the community) or bottom-up (designing based on reconstructed metabolic networks of constituent species) [14].

- Build: Construct the designed microbiome using methods like synthetic inoculation or self-assembly from a defined inoculum.

- Test: Evaluate the constructed microbiome's function against specified metrics using multi-omics and physiological data.

- Learn: Analyze the outcomes to refine models and inform the next DBTL cycle, accelerating scientific discovery and biotechnological application [14].

Understanding the dynamics of microbial communities requires a framework of core ecological concepts. Community assembly describes the processes governing the formation and composition of microbial communities, driven by both deterministic factors (like environmental selection) and stochastic processes (like random immigration) [5]. Resilience is the capacity of a community to recover its original state after a disturbance, emerging from both individual organism adaptations and community-level coordination [16]. Functional stability refers to the maintenance of ecosystem processes despite fluctuations in community composition, often underpinned by mechanisms like functional redundancy [16] [17]. These interconnected concepts are essential for analyzing and predicting microbial community dynamics in diverse environments, from engineered systems to natural soils [5] [16].

Quantitative Foundations: Metrics and Data

Tracking changes in microbial communities over time requires robust quantitative metrics. The following table summarizes key analytical measures used in longitudinal studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Analyzing Microbial Community Dynamics

| Metric | Formula/Definition | Application Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity | ( BC{jk} = 1 - \frac{2 \sum \min(S{ij}, S{ik})}{\sum S{ij} + \sum S{ik}} ) where (S{ij}) and (S_{ik}) are the abundance of species (i) in samples (j) and (k). | Beta-diversity analysis; assessing community composition shifts over time or between conditions [16]. | Values range from 0 (identical communities) to 1 (no species in common). A low value indicates high compositional stability [16]. |

| Contrast Ratio (for Data Visualization) | ( \text{Contrast Ratio} = \frac{L1 + 0.05}{L2 + 0.05} ) where L1 is the relative luminance of the lighter color and L2 of the darker [18]. | Ensuring accessibility and readability in data visualization of complex microbial data. | Minimum 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text (WCAG Level AA). Essential for clear scientific communication [18]. |

| Community Stability Index | Not explicitly defined in results; generally reflects resistance to and recovery from disturbance. | Evaluating community resilience, often calculated from time-series abundance data [16]. | A high index indicates a community that is more resistant to change and recovers more quickly from perturbations [16]. |

| Functional Redundancy | Often inferred from the relationship between taxonomic and functional diversity metrics from metagenomic data [17]. | Assessing whether multiple taxa perform the same function, thus buffering ecosystem processes [17]. | High functional redundancy can maintain functional stability even when taxonomic composition shifts [17]. |

Advanced modeling approaches, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), have been successfully applied to predict species-level abundance dynamics in complex communities. These models can accurately forecast microbial dynamics up to 2-4 months into the future using historical relative abundance data, demonstrating their power for temporal analysis [5].

Experimental Protocols for Community Analysis

Protocol: Predicting Temporal Dynamics with Graph Neural Networks

This protocol outlines the procedure for using a GNN to forecast future microbial community composition based on historical data [5].

1. Sample Collection and Sequencing

- Frequency: Collect samples longitudinally. A high-frequency sampling regime (e.g., 2-5 times per month) is ideal for capturing dynamics [5].

- Duration: Long-term studies (3-8 years) provide robust data for model training and validation [5].

- Method: Use 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing for cost-effective community profiling. Classify Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) using an ecosystem-specific database (e.g., MiDAS 4 for wastewater) for high-resolution taxonomy [5].

2. Data Preprocessing and Clustering

- Abundance Filtering: Select the top N most abundant ASVs (e.g., top 200) that represent a significant portion of the total reads (e.g., >50%) to reduce noise from rare taxa [5].

- Pre-clustering: Cluster ASVs into smaller, interacting groups to improve model performance. The following table compares clustering methods: Table 2: Comparison of Pre-clustering Methods for Microbial Abundance Data

| Clustering Method | Description | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Network Interaction Strengths | Clusters based on inferred interaction strengths from the graph network itself [5]. | Achieved the best overall prediction accuracy across multiple datasets [5]. |

| Ranked Abundances | Groups ASVs by their ranked abundance (e.g., in groups of 5) [5]. | Generally resulted in very good prediction accuracy, comparable to graph-based clustering [5]. |

| Improved Deep Embedded Clustering (IDEC) | An unsupervised algorithm that decides the optimal cluster number itself [5]. | Enabled some of the highest accuracies but produced a larger spread in accuracy between clusters, making it less reliable [5]. |

| Biological Function | Groups ASVs into known functional guilds (e.g., PAOs, AOB, NOBs) [5]. | Generally resulted in lower prediction accuracy compared to other methods, except in specific cases [5]. |

3. Model Training and Architecture

- Input: Use moving windows of 10 consecutive historical time points for each cluster of ASVs [5].

- Architecture: The GNN consists of several layers:

- Graph Convolution Layer: Learns and extracts interaction features between ASVs within a cluster [5].

- Temporal Convolution Layer: Extracts temporal features across the time-series data [5].

- Output Layer: Uses fully connected neural networks to predict the relative abundances of each ASV for future time points [5].

- Output: The model predicts relative abundances for a specified number of future time points (e.g., up to 10 time points ahead, equivalent to 2-4 months) [5].

4. Model Validation

- Data Splitting: Perform a chronological 3-way split of the time-series data for each individual site into training, validation, and test datasets [5].

- Accuracy Metrics: Evaluate prediction accuracy against the held-out test data using metrics like Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) [5].

Protocol: Assessing Resilience via Time-Resolved Multiomics

This protocol is designed to investigate the mechanisms of microbial community resilience in response to environmental disturbances, such as drought and rewetting in arid soils [16].

1. Experimental Design and Sampling

- Site Selection: Choose a site with a predictable environmental fluctuation (e.g., arid soil subject to monsoon seasons) [16].

- Temporal Sampling: Collect soil samples from multiple biological replicates (e.g., 4 sites) across multiple time points that capture pre-disturbance, during disturbance, and post-disturbance/recovery phases (e.g., 8 time points over 5 months) [16].

- Physicochemical Data: Concurrently measure environmental parameters such as soil moisture, temperature, and vegetation density (NDVI) [16].

2. Multiomics Data Generation

- Community Profiling:

- Metabolomic Profiling:

- Use Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry (FTICR-MS) to characterize the composition of soil organic matter and microbial metabolites [16].

3. Data Integration and Analysis

- Community Stability: Calculate beta-diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) to test for significant shifts in taxonomic composition across time [16]. Resilience is indicated if post-disturbance communities return to pre-disturbance composition.

- Functional and Metabolic Shifts: Analyze FTICR-MS data to see if organic matter composition changes significantly despite taxonomic stability, indicating metabolic reorganization [16].

- Genomic Basis of Adaptation: Analyze MAGs to identify individual microbial adaptations (e.g., stress response genes, dormancy-related genes) that contribute to community-level resilience [16].

- Network Analysis: Construct co-occurrence networks to identify how microbial interactions reorganize between environmental states, which can reveal keystone taxa [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Microbial Community Dynamics

| Category / Item | Specific Examples / Specifications | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing & Molecular Biology | ||

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Primers targeting V3-V4 hypervariable region; MiDAS 4 database for classification [5]. | Cost-effective profiling of microbial community composition and taxonomic structure at high resolution (ASV level) [5]. |

| HiFi Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | PacBio long-read sequencing platforms [19]. | Enables precise taxonomic profiling, reconstruction of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs), and precise functional gene analysis, providing deeper insights than short-reads [19]. |

| FTICR-MS | Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry [16]. | Characterizes the molecular composition of soil organic matter and microbial metabolites, linking community function to metabolic outputs [16]. |

| Computational Tools & Software | ||

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Workflow | "mc-prediction" workflow [5]. | A specialized tool for predicting future microbial community dynamics using historical abundance data via graph neural networks [5]. |

| Metagenomic Analysis | HUMAnN 4 for functional profiling; CoverM for genome coverage analysis [16] [19]. | Precisely profiles the abundance of microbial metabolic pathways from metagenomic data; quantifies relative abundance of MAGs in community [16] [19]. |

| R Packages for Visualization | urbnthemes package for ggplot2 [20]. |

Applies consistent, accessible styling and color palettes to data visualizations, ensuring clarity and adherence to contrast guidelines [20]. |

| Accessibility & Color Contrast Checkers | WebAIM Contrast Checker; WAVE browser extension [21] [22]. | Ensures that data visualizations meet WCAG 2.2 guidelines (e.g., 4.5:1 contrast ratio for text), making them readable for all users, including those with color vision deficiencies [21] [22]. |

| Solvent Blue 35 | Solvent Blue 35, CAS:17354-14-2, MF:C22H26N2O2, MW:350.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide | N-Methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide, CAS:769-49-3, MF:C7H8N2O2, MW:152.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Cutting-Edge Techniques for Profiling and Predicting Community Dynamics

In the field of microbial ecology, high-throughput sequencing technologies have revolutionized our ability to decipher the composition and function of complex microbial communities. The two predominant strategies, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing, provide complementary yet distinct lenses for studying microbiomes [23]. The choice between these methods is a critical initial step in research design, impacting cost, analytical depth, and the fundamental biological questions that can be addressed. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these technologies, framed within the context of analyzing microbial community dynamics, to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate methodology for their investigations.

Fundamental Principles

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing is a targeted amplicon sequencing approach. It relies on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify one or more hypervariable regions (V1-V9) of the 16S rRNA gene, a conserved genetic marker present in all bacteria and archaea [24] [25]. The resulting sequences are clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and compared against reference databases like SILVA or Greengenes for taxonomic classification [26] [23].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing is an untargeted approach. It involves fragmenting all genomic DNA in a sample into small pieces, sequencing these fragments randomly, and then using bioinformatics to reconstruct the sequences and identify the organisms and genes present [27] [24]. This method sequences the entire genetic content, enabling the profiling of all domains of life—bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and protists—from a single sample [28] [29].

Comparative Technical Specifications

The following table summarizes the core technical differences between the two methodologies, which are crucial for experimental design.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of 16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Factor | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Targeted PCR amplification of a specific gene region [24] | Untargeted, random fragmentation and sequencing of all DNA [27] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus level (sometimes species); high false-positive rate at species level [24] [28] | Species and strain-level resolution [24] [29] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [24] [25] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Protists [24] [28] |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect prediction via tools like PICRUSt (not direct) [24] | Direct characterization of functional genes and metabolic pathways [27] [24] |

| Host DNA Interference | Low (PCR enriches for microbial target) [28] | High (requires host DNA depletion or high sequencing depth) [24] [28] |

| Recommended Sample Type | All types, especially low-microbial-biomass/high-host-DNA samples (e.g., skin swabs) [28] | All types, best for high-microbial-biomass samples (e.g., stool) [24] [28] |

Quantitative Performance and Cost Analysis

Empirical comparisons reveal significant differences in the output and capabilities of the two techniques. Studies consistently show that shotgun sequencing detects a greater portion of microbial diversity, particularly among less abundant taxa, which are often missed by 16S sequencing [26] [29]. For instance, in a study of the chicken gut microbiota, shotgun sequencing identified 256 statistically significant changes in genera abundance between gut compartments, compared to only 108 identified by 16S sequencing [26].

While 16S data is generally sparser and shows lower alpha diversity than shotgun data, the overall patterns can be correlated. One study reported an average correlation of 0.69 for genus abundances between the two methods when considering common taxa [26]. Furthermore, both techniques have demonstrated the ability to train machine learning models that can predict disease states, such as pediatric ulcerative colitis, with comparable high accuracy [30].

Table 2: Performance and Logistical Considerations

| Aspect | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics | Shallow Shotgun |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Cost per Sample | ~$50 USD (Lower cost) [24] | Starting at ~$150 USD (Higher cost) [24] | Close to 16S cost [24] [28] |

| Sensitivity to Low-Abundance Taxa | Lower power to identify less abundant taxa [26] | Higher power with sufficient sequencing depth [26] | Intermediate |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner to Intermediate [24] | Intermediate to Advanced [24] | Intermediate |

| Minimum DNA Input | Low (can work with <1 ng DNA) [28] | Higher (typically >1 ng/μL) [28] | Similar to standard shotgun |

| Data Output | Sequences only the 16S gene region | Sequences all genomic DNA; more data-rich [24] | Reduced data per sample but retains multi-kingdom coverage [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The standard workflow for 16S rRNA gene sequencing involves several key stages, from sample preparation to bioinformatic analysis.

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Extract microbial DNA from the sample using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp Powerfecal DNA Kit, Dneasy PowerLyzer Powersoil Kit) following the manufacturer's instructions. Mechanical lysis is often recommended for thorough cell disruption [30] [29].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target hypervariable region (e.g., V4 or V3-V4) of the 16S rRNA gene using universal primer pairs (e.g., 515F/806R). The PCR reaction incorporates unique barcodes for each sample to enable multiplexing [30] [24].

- Library Preparation: Clean up the amplified PCR product to remove reagents and primers. Size-select the DNA to ensure the correct fragment size is retained [24].

- Pooling and Sequencing: Quantify the purified libraries and pool them in equimolar ratios. Sequence the pooled library on an Illumina MiSeq or similar platform using a 2x150bp or 2x250bp paired-end protocol [30].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Pre-processing: Use tools like DADA2 or QIIME 2 to trim primers, filter low-quality reads and chimeras, and merge paired-end reads [29].

- Clustering/Denoising: Generate OTUs (e.g., with MOTHUR) or ASVs (e.g., with DADA2) to cluster sequences into taxonomic units [26] [31].

- Taxonomy Assignment: Assign taxonomy to OTUs/ASVs by aligning them to reference databases such as SILVA, Greengenes, or the RDP [23] [29].

Workflow for Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

Shotgun metagenomics involves a more complex preparation and analytical process to handle the entirety of genomic content.

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. The quality of input DNA is paramount for all downstream steps [25]. Kits like the NucleoSpin Soil Kit are commonly used.

- Library Preparation: Fragment the purified DNA via physical shearing or enzymatic tagmentation (e.g., using Nextera XT kits). This step randomly breaks the DNA into small fragments. Adapters and sample-specific barcodes are then ligated to the fragments [30] [25].

- Sequencing: Pool the barcoded libraries and sequence on a high-output platform like the Illumina NextSeq or NovaSeq, generating tens of millions of paired-end reads (e.g., 2x150bp) per sample to achieve sufficient depth [30].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control and Host Removal: Trim adapters and low-quality bases with tools like Trim Galore! or KneadData. Remove reads that align to the host genome (e.g., human GRCh38) using Bowtie2 [30] [29].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Classify reads using reference-based tools like MetaPhlAn or Kraken2, which align reads to comprehensive databases of microbial genomes (e.g., NCBI RefSeq, GTDB) [24] [29].

- Functional Profiling: Assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs and predict genes. Annotate these genes against functional databases (e.g., KEGG, eggNOG) using tools like HUMAnN to determine the abundance of metabolic pathways and functional genes [24] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of microbiome sequencing requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their applications.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Microbiome Sequencing

| Item | Function/Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples; critical for downstream success. | QIAamp Powerfecal DNA Kit (Qiagen), Dneasy PowerLyzer Powersoil Kit (Qiagen), NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel) [30] [29] |

| PCR Primers | Targeted amplification of specific 16S rRNA hypervariable regions for amplicon sequencing. | 515F/806R for V4 region [30] |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries, including fragmentation, adapter ligation, and indexing. | Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) [30] [25] |

| Reference Databases (16S) | Taxonomic classification of 16S rRNA sequence reads. | SILVA, Greengenes, Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) [23] [29] |

| Reference Databases (Shotgun) | Taxonomic classification and functional annotation of metagenomic reads. | NCBI RefSeq, GTDB, UHGG [29] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software for data processing, quality control, taxonomic assignment, and functional analysis. | QIIME 2, MOTHUR (16S); MetaPhlAn, HUMAnN, Kraken2, DRAGEN (Shotgun) [27] [24] [23] |

| N-Stearoylglycine | N-Stearoylglycine, CAS:158305-64-7, MF:C20H39NO3, MW:341.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tin(II) oxalate | Tin(II) oxalate, CAS:814-94-8, MF:C2O4Sn, MW:206.73 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application in Microbial Community Dynamics

Understanding microbial community dynamics—such as succession, stability, and response to perturbation—is a central goal in microbial ecology. The choice of sequencing technology directly impacts the insights gained.

16S rRNA Sequencing is highly effective for tracking broad-scale changes in community structure over time or across conditions. For example, in a study of artificial selection for chitin-degrading communities, 16S sequencing revealed rapid succession where Gammaproteobacteria (primary degraders) were succeeded by cheaters and grazing organisms, explaining observed fluctuations in enzymatic activity [31]. This makes 16S ideal for large-scale longitudinal studies where the primary focus is on monitoring shifts in taxonomic composition and beta-diversity without the need for functional details.

Shotgun Metagenomics provides a system-level view, enabling the linkage of taxonomic shifts to functional changes. It can identify the specific genes and pathways (e.g., chitinase enzymes) that are enriched during community succession [31]. Furthermore, by providing strain-level resolution, shotgun sequencing can track specific strains within a community, uncovering dynamics that are invisible at the genus or species level provided by 16S. This is crucial for understanding mechanisms behind community assembly, stability, and functional output.

Both 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing are powerful, yet distinct, tools for profiling microbial communities. 16S sequencing offers a cost-effective, straightforward method for answering questions about taxonomic composition and diversity, making it ideal for large-scale studies or when focusing on well-defined bacterial and archaeal communities. Shotgun metagenomics provides a more comprehensive view, delivering higher taxonomic resolution, multi-kingdom coverage, and direct insight into the functional potential of the microbiome, albeit at a higher cost and computational burden.

The decision between them should be guided by the research question, budget, sample type, and analytical capabilities. For research focused on microbial community dynamics, 16S is excellent for tracking structural changes, while shotgun is indispensable for uncovering the functional mechanisms and fine-scale strain dynamics that underpin those changes. As sequencing costs continue to decrease and bioinformatic tools become more accessible, shotgun metagenomics, particularly the "shallow shotgun" approach, is poised to become an increasingly standard tool for in-depth microbiome analysis.

In microbial community analysis, standard high-throughput sequencing protocols generate data in relative abundances, where the increase of one taxon artificially forces the decrease of all others in the profile [32]. This compositional nature of sequencing data limits biological interpretation, as it cannot distinguish whether a taxon's increase is due to actual growth or the decline of other community members. Absolute quantification resolves this ambiguity by measuring the exact number of microbial cells or genome copies in a sample, enabling true cross-comparison between samples and studies [33] [32].

Spike-in controls provide a powerful experimental approach for converting relative sequencing data to absolute abundances by adding known quantities of foreign biological materials to samples prior to DNA extraction [32] [34]. These controls track efficiency throughout the entire workflow—from cell lysis and DNA extraction to PCR amplification and sequencing—allowing researchers to compute scaling factors that transform relative proportions into absolute counts [35]. This approach is becoming increasingly crucial in both basic research and applied settings, such as pharmaceutical manufacturing where accurate microbial load assessment is critical for sterility assurance and patient safety [36].

Types of Spike-in Controls

Two principal types of spike-in controls are used in microbial sequencing studies, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 1: Comparison of Spike-in Control Types

| Control Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Cell Controls | Intact microbial cells (often inactivated) with different cell wall properties [34]. | Controls for DNA extraction efficiency and cell lysis bias; accounts for differential lysis of Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacteria [33] [34]. | Potential similarity to native microbiota; may require a priori community knowledge [32]. |

| Synthetic DNA Controls | Engineered DNA sequences with negligible similarity to natural genomes [32]. | Highly customizable; minimal risk of confounding native data; stable and reproducible [32]. | Does not control for cell lysis efficiency; requires careful GC-content design to address amplification bias [32]. |

Commercial Spike-in Solutions

Several optimized spike-in controls are commercially available, providing standardized reagents for absolute quantification:

Table 2: Commercial Spike-in Control Products

| Product Name | Composition | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I | Equal cell numbers of Imtechella halotolerans (Gram-negative) and Allobacillus halotolerans (Gram-positive) [34]. | High microbial load samples (e.g., feces, cell culture) [34]. | Controls for extraction bias across cell wall types; provided fully inactivated [34]. |

| synDNA Spike-in Pools | 10 synthetic DNA molecules (2,000 bp) with variable GC content (26-66%) [32]. | Shotgun metagenomics and amplicon sequencing [32]. | Covers range of GC contents to minimize amplification bias; negligible identity to NCBI database sequences [32]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards | Defined mixtures of 8-12 bacterial species with published reference genomes [37]. | Method validation and benchmarking [37]. | Well-characterized composition; useful for validating absolute quantification methods [37]. |

Experimental Design and Implementation

Workflow for Absolute Quantification

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for implementing spike-in controls in microbial community studies:

Determining Spike-in Concentration

The optimal spike-in concentration depends on the expected microbial load of the sample. As a general guideline:

- For high biomass samples (e.g., stool, soil): Spike-in should comprise 0.1-1% of total DNA [37]

- For low biomass samples (e.g., water, swabs): Spike-in may comprise 10-50% of total DNA [34] [37]

It is critical to perform preliminary tests to ensure spike-in reads are detectable but do not dominate the sequencing library, typically aiming for 0.5-5% of total sequencing reads [37].

Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Whole Cell Spike-in for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

This protocol utilizes commercial whole cell spike-in controls to achieve absolute quantification in bacterial community analysis [34] [37].

Materials Required:

- ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I (High Microbial Load) [34]

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit) [37]

- PCR reagents for 16S rRNA gene amplification

- Sequencing library preparation reagents

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw spike-in control and samples on ice.

- Spike-in Addition: Add 10 μL of spike-in control to 1 mL of sample, representing approximately 10% of total DNA [37]. Vortex thoroughly.

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA using preferred method, ensuring proper lysis conditions for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [34] [37].

- Quality Control: Measure DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA BR Assay) [37].

- Library Preparation: Amplify the V1-V9 regions of the 16S rRNA gene using full-length primers (27F/1492R) with 25-35 PCR cycles [37].

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on appropriate platform (e.g., MinION Mk1C for nanopore sequencing) [37].

Protocol 2: Synthetic DNA Spike-in for Shotgun Metagenomics

This protocol employs synthetic DNA spike-ins for absolute quantification in shotgun metagenomic studies [32].

Materials Required:

- synDNA pool (10 synthetic DNAs with varying GC content) [32]

- DNA extraction kit

- Library preparation reagents for shotgun metagenomics

Procedure:

- synDNA Preparation: Dilute synDNA pool to working concentration (typically 0.001-0.1 ng/μL) [32].

- Spike-in Addition: Add 5 μL of diluted synDNA pool to 45 μL of extracted DNA, matching the GC content distribution to expected community profile [32].

- Library Preparation: Proceed with standard shotgun metagenomic library preparation.

- Sequencing: Sequence on appropriate platform (Illumina recommended for GC bias assessment) [32].

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Data Processing Workflow

The computational workflow for analyzing spike-in controlled data involves both standard bioinformatic processing and specialized absolute abundance calculation:

Absolute Abundance Calculation

The DspikeIn R package (available through Bioconductor) provides a comprehensive toolkit for absolute abundance calculation from spike-in controlled data [35]. The fundamental calculation is:

Scaling Factor (S) = (Expected spike-in molecules) / (Observed spike-in reads)

Absolute Abundance (A) = (Relative abundance of taxon × Total reads × S)

The DspikeIn package implements this with additional corrections for technical variation and GC content bias [35].

Key Functions in DspikeIn:

validate_spikein_clade(): Confirms spike-in identificationcalculate_spikeIn_factors(): Computes sample-specific scaling factorsconvert_to_absolute_counts(): Transforms relative to absolute abundancesplot_spikein_tree_diagnostic(): Visualizes spike-in performance [35]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Spike-in Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Cell Spike-ins | ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control I (D6320) [34] | Contains Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; ideal for 16S rRNA gene sequencing studies. |

| Synthetic DNA Spike-ins | synDNA pools (custom design) [32] | Engineered sequences; optimal for shotgun metagenomics with minimal cross-mapping. |

| Reference Standards | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (D6300) [37] | Validates method accuracy; use for initial protocol optimization. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit [37] | Ensures efficient lysis of diverse bacterial cell types. |

| Quantification Reagents | Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit [37] | Fluorometric quantification superior for low biomass samples. |

| Analysis Software | DspikeIn R package [35] | Comprehensive pipeline for absolute abundance calculation. |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Viability Assessment with PMAxx Treatment

For distinguishing between viable and non-viable bacteria, spike-in controls can be integrated with viability dyes such as PMAxx. This modified intercalating dye penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells and cross-links DNA upon light exposure, preventing its amplification [33].

Integrated Protocol:

- Add PMAxx dye to sample (final concentration 50-100 μM)

- Incubate in dark for 10 minutes

- Expose to bright light for 15 minutes (photo-induced cross-linking)

- Add whole cell spike-in controls

- Proceed with DNA extraction and sequencing [33]

This approach enables absolute quantification of viable microbial populations, crucial for applications such as sterilization validation and probiotic potency testing [33].

Method Validation and Quality Control

Comprehensive validation should include:

- Linearity testing: Serial dilution of spike-ins to confirm quantitative response [32] [37]

- Limit of detection: Determine minimum spike-in concentration yielding reliable quantification [37]

- Precision assessment: Replicate measurements to establish technical variability [35]

- Comparison to reference methods: Correlate with culture-based counts (CFU) or flow cytometry where feasible [33] [37]

Implementing spike-in controls transforms standard relative microbiome data into quantitative absolute abundance measurements, enabling robust cross-sample comparisons and accurate assessment of microbial load dynamics. The protocols outlined here provide researchers with practical guidance for selecting appropriate controls, designing experiments, and analyzing resulting data. As the field moves toward more quantitative frameworks in microbial ecology and pharmaceutical bioburden assessment [36], spike-in methods will play an increasingly vital role in generating reproducible, biologically meaningful results.

Understanding and predicting the temporal dynamics of microbial communities at the species level is a central challenge in microbial ecology, with significant implications for environmental management, human health, and drug development. Traditional models often struggle to capture the complex, non-linear interactions between microbial species that drive community dynamics. The emergence of graph neural networks (GNNs) offers a powerful framework for addressing this challenge by explicitly modeling microbial communities as relational networks, where nodes represent species and edges represent potential ecological interactions [5] [38]. This application note details the implementation of GNN-based predictive models for forecasting species-level abundance, providing researchers with practical protocols and resources for applying these advanced computational techniques to longitudinal microbial datasets.

Background and Significance

Microbial communities are complex systems characterized by diverse interaction types—including positive (mutualism, commensalism), negative (competition, amensalism), and neutral relationships—that collectively shape community structure and function [1]. The ability to accurately predict how these interactions influence future species abundances enables proactive management in applications ranging from wastewater treatment optimization to personalized medicine [5] [39] [31]. GNNs are particularly suited to this task because they incorporate an inductive bias that respects the set-like nature of microbial communities, enforcing permutation invariance and granting combinatorial generalization [38]. This allows models to learn from historical abundance patterns and infer future dynamics without requiring complete mechanistic understanding of all underlying ecological processes.

GNN Architecture for Microbial Community Prediction

Model Design Principles

The GNN architecture for microbial abundance prediction operates on the fundamental principle of learning relational dependencies between species through graph convolutional layers that extract interaction features, followed by temporal convolutional layers that capture dynamic patterns across time [5]. This architecture conceptualizes the microbial community as a graph where:

- Nodes represent individual microbial taxa (e.g., amplicon sequence variants - ASVs)

- Edges represent inferred ecological interactions between taxa

- Node features correspond to temporal abundance patterns

The model employs a multi-head attention mechanism that enables the network to jointly attend to information from different interaction subspaces, capturing the diverse nature of microbial relationships [40]. This design allows the model to learn both the strength and directionality of species interactions directly from abundance data, without requiring a priori knowledge of interaction mechanisms.

Core Architectural Components

Table 1: Core Components of GNN Architecture for Microbial Abundance Prediction

| Component | Function | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolution Layer | Learns interaction strengths between microbial species | Extracts relational features using polynomial graph filters; applies message-passing between connected nodes [5] [41] |

| Temporal Convolution Layer | Captures abundance patterns across time | Uses 1D convolutional operations across sequential measurements; identifies seasonal and non-seasonal dynamics [5] |

| Multi-Head Attention Mechanism | Identifies important interactions across different representation subspaces | Computes attention weights for target nodes; enables model to focus on most relevant ecological relationships [40] |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | Generates final abundance predictions | Fully connected neural network that maps extracted features to future abundance values [5] [40] |

Figure 1: GNN Model Architecture for Abundance Prediction. The workflow processes historical abundance data through sequential layers to generate future abundance predictions.

Experimental Protocols

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

Protocol 4.1.1: Microbial Community Data Curation

- Sample Collection: Collect longitudinal microbial community samples with consistent temporal intervals. Optimal sampling frequency is 2-5 times per month over extended periods (3-8 years recommended) [5].

- Sequence Processing: Process raw sequencing data through standard amplicon sequence analysis pipelines (DADA2 recommended) to generate amplicon sequence variant (ASV) tables [5] [31].

- Abundance Filtering: Filter ASVs to retain the top 200 most abundant taxa, which typically represent 52-65% of all sequence reads and the majority of functional biomass [5].

- Data Partitioning: Chronologically split datasets into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets to ensure temporally realistic evaluation [5].

- Normalization: Apply relative abundance normalization (converting counts to proportions) to account for sampling depth variation while preserving compositional structure.

Protocol 4.1.2: Graph Construction

- Node Definition: Define nodes as individual microbial taxa (ASVs) with initial node features corresponding to their abundance vectors across time.

- Edge Construction: Implement one of the following pre-clustering methods to define relational edges:

- Graph-based clustering: Use graphical clustering algorithms on network interaction strengths derived from the GNN itself [5]

- Ranked abundance clustering: Group ASVs by abundance ranks in clusters of 5 [5]

- Biological function clustering: Cluster by known functional groups (e.g., PAOs, GAOs, filamentous bacteria) [5]

- Window Selection: Create moving windows of 10 consecutive historical time points as model inputs, with the subsequent 10 time points as prediction targets [5].

Model Training and Implementation

Protocol 4.2.1: GNN Training Procedure

- Architecture Configuration: Implement a 5-layer GNN with multi-head Graph Attention Convolution (GATConv) mechanisms for Model-to-Target and Target-to-Target interaction layers [40].

- Embedding Generation: Use BioBERT (version 1.1) to tokenize and generate initial 768-dimensional embeddings for biological entities [40].

- Parameter Initialization: Initialize weights using Xavier uniform initialization and set hidden dimensions to 2,048 (8 attention heads × 256 dimensions per head) [40].

- Model Training: Train using chronological splits with early stopping based on validation loss to prevent overfitting.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize learning rate (typical range: 0.001-0.0001), batch size (16-32), and dropout rate (0.2-0.5) via Bayesian optimization.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of GNN Models for Microbial Abundance Prediction

| Dataset | Prediction Horizon | Clustering Method | Bray-Curtis Similarity | Key Predictive Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 Danish WWTPs [5] | 10 time points (2-4 months) | Graph-based clustering | High (0.85-0.92) | Thalassotalea, Cellvibrionaceae |

| 24 Danish WWTPs [5] | 20 time points (8 months) | Ranked abundance clustering | Moderate to High (0.75-0.88) | Crocinitomix, Terasakiella |

| Human Gut Microbiome [5] | 10-15 time points (2-3 months) | Graph-based clustering | High (0.82-0.90) | Functional groups rather than specific taxa |

| Laboratory Chitin Degradation [31] | Community succession peaks | Biological function clustering | Variable (dependent on transfer timing) | Gammaproteobacteria |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for GNN-based Prediction. End-to-end protocol from raw data to predictive insights.

Model Evaluation and Interpretation

Protocol 4.3.1: Performance Assessment

- Metric Calculation: Evaluate model performance using multiple metrics:

- Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between predicted and observed community composition

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for individual taxon abundance predictions

- Mean Squared Error (MSE) to penalize larger prediction errors [5]

- Temporal Validation: Assess prediction accuracy across different forecast horizons (5, 10, 15, 20 time points) to determine optimal practical prediction limits.

- Cluster-wise Analysis: Evaluate performance variation across different pre-clustering methods to identify optimal grouping strategies for specific ecosystem types.

- Abundance-stratified Evaluation: Calculate accuracy separately for high, medium, and low abundance taxa to identify potential prediction biases.

Protocol 4.3.2: Ecological Interpretation

- Interaction Network Extraction: Derive microbial interaction networks from trained GNN weights to identify strong positive and negative relationships between taxa.

- Keystone Species Identification: Detect potential keystone species through centrality analysis of the inferred interaction network.

- Functional Validation: Correlate predicted abundance changes with known functional capacities of taxa (e.g., using databases like MiDAS Field Guide) [5].

- Dynamic Analysis: Track how predicted interaction strengths vary across different environmental conditions or temporal phases.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GNN-based Microbial Prediction

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| mc-prediction Workflow [5] | Open-source GNN implementation for community prediction | Python workflow available at https://github.com/kasperskytte/mc-prediction |

| MiDAS 4 Database [5] | Ecosystem-specific taxonomic reference database | Provides high-resolution species-level classification for wastewater treatment plant microbes |