Beyond the Petri Dish: Innovative Strategies for Cultivating the Unculturable Microbial Majority

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest scientific advances and methodologies for cultivating previously unculturable microorganisms.

Beyond the Petri Dish: Innovative Strategies for Cultivating the Unculturable Microbial Majority

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest scientific advances and methodologies for cultivating previously unculturable microorganisms. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational reasons for unculturability, details cutting-edge cultivation techniques like high-throughput dilution-to-extinction and in-situ encapsulation, and offers optimization strategies for microbial growth. It further addresses the critical validation of cultivation success through genomic comparisons and highlights the profound implications for discovering novel antibiotics, such as clovibactin, and for expanding our functional understanding of microbial ecology and evolution.

The Uncultured Majority: Understanding the Scale and Significance of Hidden Microbial Life

For researchers in microbiology and drug development, a fundamental challenge persists: the vast majority of microbial diversity on Earth resists growth under standard laboratory conditions. This phenomenon, known as the "Great Plate Count Anomaly," describes the discrepancy of several orders of magnitude between the number of microbial cells observed microscopically in an environmental sample and the number of colonies that actually grow on a Petri plate [1] [2]. It is estimated that while traditional cultivation methods allow us to study only about 0.1% to 1.0% of microbial species in many environments, the remaining 99% represent an untapped reservoir of genetic and metabolic diversity, including potential novel natural products [1] [3]. This technical support center is designed to provide actionable troubleshooting guides and methodologies to help you overcome these cultivation barriers and access this "uncultured majority."

FAQs: Understanding the Core Challenge

1. What exactly does "unculturable" mean in a practical research context?

"Unculturable" is a operational term indicating that a microorganism cannot be grown using current standard laboratory culturing techniques. It does not mean the organism can never be cultured [1]. The term highlights a gap in our knowledge about the organism's specific biological and environmental needs. These microbes are often metabolically active in their native environment but fail to proliferate when transferred to artificial media [4].

2. What are the primary reasons our laboratory cultivation attempts fail?

Failure is typically not due to a single factor but a combination of several:

- Inappropriate Nutrient Levels: Standard laboratory media are often too nutrient-rich, which can inhibit or kill oligotrophic (nutrient-preferring) bacteria from environments like open ocean or soil [5] [2].

- Absence of Essential Growth Factors: The laboratory medium may lack specific signaling molecules, vitamins, or other growth factors that are provided by other organisms in a complex community [1] [4].

- Dependence on Other Microorganisms (Syntrophy): Some bacteria rely on the metabolic byproducts of helper species for growth. Isolating them disrupts these essential cross-feeding relationships [2] [4].

- Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State: Many bacteria enter a dormant, low-metabolism state in response to stress and will not form colonies on plates, even though they are alive [3].

3. How can we identify if an uncultured microbe is even present in our sample?

Cultivation-independent molecular techniques are key for detecting these organisms.

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: This is the primary tool. By extracting DNA directly from an environmental sample (e.g., soil, water), amplifying the 16S rRNA gene, and sequencing it, you can identify the phylogenetic "fingerprints" of microbes without needing to culture them [1] [6].

- Metagenomics: Shotgun sequencing of all the DNA in a sample allows you to reconstruct full or partial genomes of uncultured organisms, providing hypotheses about their metabolic capabilities and potential growth requirements [7] [6].

4. Why is overcoming this anomaly critical for drug discovery?

Bacteria are a prolific source of bioactive natural products. The "discovery void" of new antibiotic classes since the late 1980s is partly attributed to the repeated isolation of the same, culturable bacteria [1]. Uncultured phyla are believed to harbor the majority of microbial natural product diversity, and accessing them is essential for discovering new classes of antibiotics, anticancer agents, and other pharmaceuticals [1].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: Low Microbial Yield on Standard Media

Problem: The number of colonies on your plates is far lower than the direct cell count from your sample.

Solutions:

- Reduce Nutrient Concentration: Use diluted standard media (e.g., 1/10 or 1/100 strength R2A) or create low-nutrient media using filtered water from your sample's environment [5] [2].

- Prolong Incubation Time: Many slow-growing bacteria will not form visible colonies in the standard 1-2 day incubation period. Extend incubation times to several weeks or even months [4].

- Use Alternative Gelling Agents: Agar can contain inhibitory compounds. Test gellan gum as a solidifying agent, which has been shown to improve the growth of some fastidious microbes [4].

- Supplement with Soil or Environmental Extract: Add filter-sterilized extract from the sample's native environment (e.g., soil extract) to the medium to introduce natural nutrients and trace elements [4].

Guide 2: Cultivating a Specific, Previously Uncultured Phylotype

Problem: Molecular data (e.g., 16S sequencing) confirms the presence of a target uncultured organism (e.g., from the TM7 phylum or SAR11 clade), but you cannot get it to grow.

Solutions:

- Employ Co-culture Techniques: Cultivate your sample in the presence of a "helper" strain from the same environment. The helper strain may provide essential growth factors, remove toxic metabolites, or signal resuscitation from dormancy [1] [8].

- Simulate the Natural Environment with Diffusion Chambers/Bioreactors: Trap cells in a semi-permeable chamber that is then placed back into the native environment or an artificial system that mimics it. This allows diffusion of natural nutrients and signals while containing the cells for later isolation [1] [4].

- Apply High-Throughput Culturing (HTC) in Microplates: Use extinction culturing by serially diluting cells to a very low density (e.g., average of 1-5 cells per well) in 48- or 96-well plates containing a low-nutrient medium. This separates cells and reduces competition, allowing slow-growers to proliferate [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To isolate oligotrophic and slow-growing bacteria from aquatic environments.

Materials:

- Filter-sterilized (0.2 µm) water from the sample environment, used as the cultivation medium.

- 48-well or 96-well non-tissue-culture-treated microplates.

- DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) stain and fluorescence microscope.

Method:

- Prepare Medium: Collect environmental water, filter-sterilize it, and restore bicarbonate buffer by sparging with COâ‚‚ followed by sterile air.

- Enumerate Inoculum: Perform a direct cell count of the source sample using DAPI staining and microscopy.

- Dilute and Dispense: Dilute the sample in the prepared medium to a final average inoculum of 1-5 cells per well. Dispense 1 mL aliquots into each well of the microplate.

- Incubate: Incubate plates in the dark at a temperature relevant to the sample's environment (e.g., 16°C for temperate marine waters) for 3-6 weeks.

- Detect Growth: After incubation, use a cell array manifold or plate reader to detect growth. For the array method, filter 200 µL from each well onto a polycarbonate membrane, stain with DAPI, and score for microcolonies under fluorescence microscopy.

- Isolate and Purify: Transfer cells from positive wells to fresh medium or solid media for further purification and identification.

Objective: To cultivate soil bacteria by maintaining a continuous connection to their natural chemical environment.

Materials:

- Inner chamber (e.g., 2L plastic container) with multiple 6mm holes drilled in its walls.

- Outer chamber (e.g., 4L plastic container).

- Polycarbonate membrane (0.4 µm pore size).

- Fresh, sieved soil from the sample site.

- Low-nutrient cultivation media (e.g., R2A, soil extract media).

Method:

- Assemble Bioreactor: Glue the polycarbonate membrane to the outer surface of the inner chamber, covering all holes. Sterilize all components.

- Load Chambers: Place the inner chamber inside the outer chamber. Fill the gap between the two chambers with the fresh, sieved soil.

- Inoculate: Add your soil sample and cultivation medium into the inner chamber.

- Incubate: Seal the bioreactor and incubate at room temperature with gentle stirring for 4 weeks. During this time, chemical compounds, nutrients, and signaling molecules diffuse from the soil through the membrane into the inner chamber.

- Sample and Isolate: After incubation, take samples from the liquid in the inner chamber, perform serial dilutions, and plate them onto solid agar plates. Incubate these plates for several weeks to isolate pure cultures.

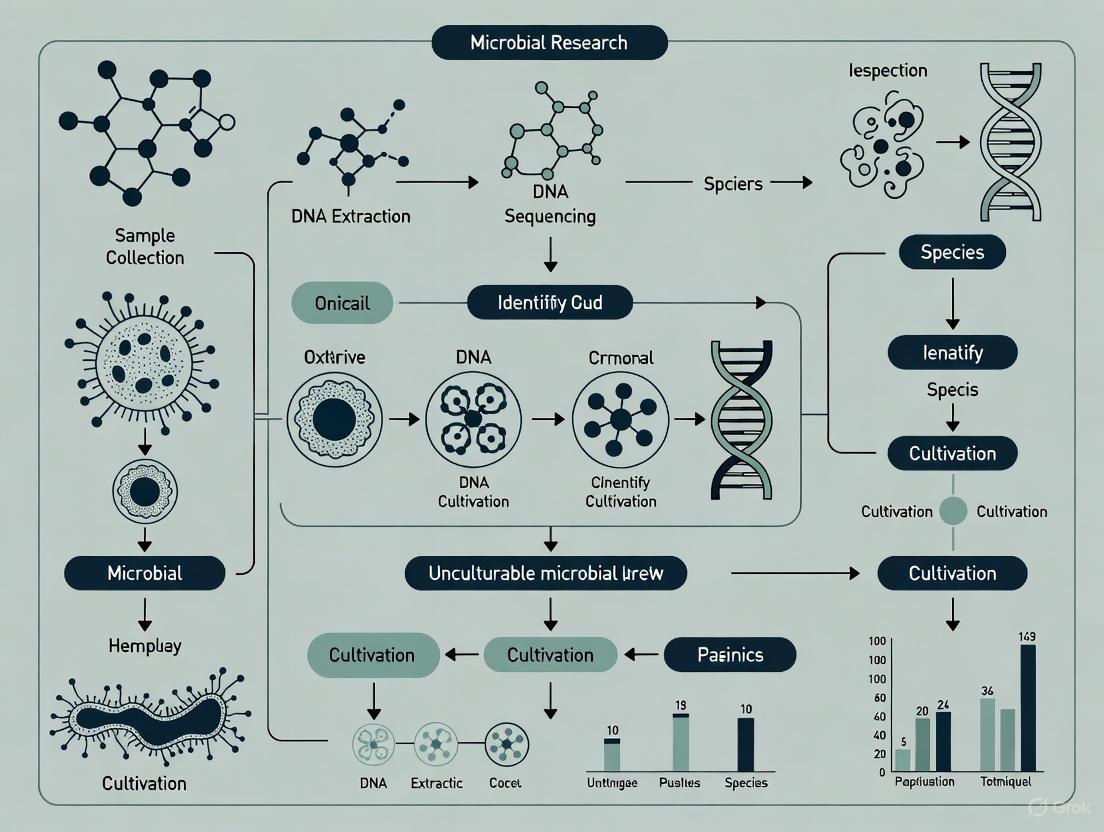

The workflow below visualizes the strategic approach to cultivating unculturable microorganisms, integrating both cultivation-independent and cultivation-dependent methods:

The table below summarizes the performance of various advanced cultivation techniques compared to traditional methods, demonstrating their efficacy in addressing the Great Plate Count Anomaly.

Table 1: Efficacy of Advanced Microbial Cultivation Techniques

| Cultivation Method | Typical Recovery Rate | Comparative Improvement Over Standard Plating | Key Isolates / Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Plating | 0.01% - 1% of total cells | (Baseline) | Commonly culturable genera | [1] [5] |

| Diffusion Chambers (in situ) | Up to 40% of total cells | 14- to 1,400-fold | Previously uncultured marine bacteria | [1] |

| High-Throughput Extinction Culturing | Up to 14% of total cells | 14- to 1,400-fold | SAR11, OM43, SAR92 clades | [5] |

| Novel Diffusion Bioreactor (Soil) | 35 previously uncultured strains | Significantly higher than conventional method | Uncultured soil bacteria from four phyla | [4] |

| Co-culture with Helper Strains | Increased diversity | 51 novel species with Rpf factor | Increased taxonomic diversity from soil | [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Cultivation of Unculturable Microorganisms

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Nutrient Media | To cultivate oligotrophic bacteria that are inhibited by standard, rich media. | Dilute Peptone (0.01%), R2A (full or 50% strength), unamended filter-sterilized environmental water. |

| Environmental Extracts | To introduce native nutrients, trace elements, and potential signaling molecules into the growth medium. | Soil Extract, Water Extract (filter-sterilized through a 0.2 µm membrane). |

| Alternative Gelling Agents | To provide a solid surface without potential inhibitory compounds found in agar. | Gellan Gum. |

| Semi-Permeable Membranes | The core component of diffusion-based techniques, allowing chemical exchange while containing cells. | Polycarbonate Membranes (0.4 µm or 0.2 µm pore size). |

| Microtiter Plates | For high-throughput extinction culturing and co-culture experiments. | 48-well or 96-well non-tissue-culture-treated plates. |

| Resuscitation-Promoting Factor (Rpf) | A bacterial cytokine that can stimulate the resuscitation of dormant cells and promote growth. | Purified Rpf or culture supernatant from Micrococcus luteus [6]. |

| Stable Isotopes (for SIP) | To label and subsequently isolate DNA from active microorganisms within a community. | ¹³C-labeled or ¹âµN-labeled substrates for Stable Isotope Probing (SIP) [7]. |

| MMBC | MMBC, MF:C20H13NO7, MW:379.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-HT2A receptor agonist-6 | 5-HT2A receptor agonist-6, CAS:1028307-48-3, MF:C18H19N3O3, MW:325.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The vast majority of the microbial world remains a scientific frontier, with an estimated 99% of microorganisms eluding standard laboratory cultivation techniques [9]. This "microbial dark matter" represents an enormous reservoir of unexplored biological diversity and genetic potential. Current genomic analyses reveal that of the 194 bacterial and archaeal phyla identified through the Genome Taxonomy Database, a staggering 85 phyla lack any cultured representatives [10]. This cultivation gap severely limits our understanding of microbial evolution, physiology, and ecology, while simultaneously restricting access to novel compounds with potential biotechnological and therapeutic applications.

The following technical support content is designed to assist researchers in overcoming the fundamental challenges in cultivating previously uncultured microorganisms. By integrating modern genomic insights with refined cultivation methodologies, this resource provides practical frameworks for bringing elusive microbial taxa into culture.

FAQs: Understanding Microbial Cultivation Challenges

1. Why are so many microorganisms considered "unculturable" using standard methods?

Most environmental microbes possess physiological traits and growth requirements that are not met by conventional cultivation approaches [11]. Key factors include:

- Unknown growth requirements: Many uncultured organisms require specific nutrients, signaling molecules, or growth factors that are not present in standard media [12]

- Slow growth rates: Oligotrophic (low-nutrient adapted) microorganisms grow slowly and are easily outcompeted by fast-growing copiotrophs in traditional rich media [10]

- Dependency on other organisms: Many microbes require metabolic byproducts from other community members through cross-feeding relationships [13]

- Low abundance: Some species exist at very low cell densities in their environments, making them difficult to enrich and isolate [13]

- Environmental sensitivity: Some organisms may be sensitive to oxygen, light, or other stressors encountered during standard cultivation attempts [12]

2. How can genomic data help us cultivate previously uncultured microorganisms?

Metagenomic and single-cell genomic information provides critical insights for designing targeted cultivation strategies [13] [14]:

- Metabolic pathway reconstruction: Genomic data can reveal an organism's nutritional requirements, energy metabolism, and potential auxotrophies [13]

- Habitat simulation: Genomic information about habitat conditions (temperature, pH, salinity) allows researchers to better mimic natural environments [11]

- Growth factor identification: Analysis can identify requirements for specific vitamins, cofactors, or signaling molecules [12]

- Community interaction mapping: Genomes can reveal dependencies on other microorganisms, guiding co-culture approaches [13]

3. What is the difference between oligotrophs and copiotrophs, and why does it matter for cultivation?

Table: Characteristics of Oligotrophic vs. Copiotrophic Microorganisms

| Characteristic | Oligotrophs | Copiotrophs |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Adaptation | Low nutrient concentrations | High nutrient concentrations |

| Growth Rate | Slow | Fast |

| Representation in Culture Collections | Underrepresented | Overrepresented |

| Environmental Abundance | Often high | Often low |

| Cultivation Media | Low nutrient media required | Grow on standard rich media |

Understanding this distinction is critical because most cultivation efforts historically have favored copiotrophs, creating a significant bias in microbial culture collections [10]. The "great plate count anomaly" refers to the observation that typically only 1% of environmental microbes form colonies on standard agar plates, primarily because most are oligotrophs inhibited by rich media [10].

4. What are the most promising new technologies for cultivating uncultured microbes?

Several innovative approaches have shown significant success:

- High-throughput dilution-to-extinction: Minimizes competition by separating individual cells in low-nutrient media [10]

- Reverse genomics: Using genetic sequences to design targeted capture and cultivation methods [15]

- Microfluidic devices: Enabling single-cell isolation and culture under controlled conditions [14]

- In situ cultivation: Allowing microorganisms to grow in their natural environment before laboratory transfer [14]

- Co-culture systems: Cultivating multiple species together to satisfy cross-feeding requirements [13]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Isate Slow-Growing or Low-Abundance Species

Symptoms:

- Fast-growing species consistently overgrow plates

- No growth observed despite confirmed viable cells in environmental samples

- Small colonies that stop growing after reaching microscopic size

Solutions:

- Apply high-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation [10]

- Use 96-well plates with low-nutrient media

- Dilute inoculum to approximately 1 cell per well

- Incubate for extended periods (6-8 weeks or longer)

- Use multiple defined media formulations mimicking natural conditions

Reduce nutrient concentrations in media [12]

- Use carbon concentrations at micromolar levels

- Avoid rich organic substrates like yeast extract or peptone

- Consider artificial media that mimic natural water or soil solutions

Extend incubation times significantly beyond standard protocols [12]

- Some oligotrophic microorganisms require 30+ days to form visible colonies

- Protect plates from desiccation during extended incubation

- Monitor growth using molecular methods (PCR) rather than visual inspection

Problem: Contamination or Overgrowth by Fast-Growing Species

Symptoms:

- Same rapidly-growing species appear regardless of media used

- Unable to obtain pure cultures of target organisms

- Molecular analysis reveals diverse species in initial inoculation that disappear after transfer

Solutions:

- Use selective physical treatments

- Pre-filtration through different pore-size filters to select for specific size fractions

- Mild heat treatment to select for spore-formers or heat-resistant species

- Centrifugation gradients to separate cells by density

Apply chemical selection methods

- Incorporate antibiotics targeted against common contaminants

- Use specific carbon sources that only support growth of desired taxa

- Incorporate humic acids or other natural compounds that stimulate target organisms [12]

Modify atmospheric conditions [12]

- Reduce oxygen concentrations (1-2% Oâ‚‚) for microaerophiles

- Increase COâ‚‚ concentrations (5%) for capnophiles

- Create anoxic conditions for strict anaerobes

Problem: Failure to Replicate Natural Environmental Conditions

Symptoms:

- Cells grow initially but cannot be subcultured

- Organisms grow in environmental samples but not in laboratory media

- Growth occurs only in mixed culture but not in isolation

Solutions:

- Incorporate chemical signals and growth factors [12]

- Add acyl homoserine lactones or other quorum-signaling molecules

- Include catalase or pyruvate to detoxify hydrogen peroxide [12]

- Add humic acids or analogs like anthraquinone disulfonate

Simulate natural substrate concentrations

- Use carbon sources at environmentally relevant concentrations (μg/L to mg/L range)

- Replicate the stoichiometry of natural waters or soils

- Include organic nitrogen and phosphorus sources at appropriate ratios

Implement co-culture approaches [13]

- Culture with helper strains that provide essential nutrients

- Use feeder layers or conditioned media from other cultures

- Create synthetic communities of 2-3 species rather than pursuing pure culture

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation for Freshwater Oligotrophs

Based on successful isolation of 627 axenic strains from freshwater ecosystems [10]

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table: Essential Reagents for Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Defined oligotrophic media (med2/med3) | Mimics natural freshwater nutrient conditions | Contains carbohydrates, organic acids, vitamins in μM concentrations |

| MM-med medium | Selects for methylotrophic bacteria | Contains methanol, methylamine as sole carbon sources |

| Catalase | Detoxifies hydrogen peroxide | Critical for preventing oxidative stress during isolation |

| SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 | Library preparation for genome sequencing | Enables verification of isolates via whole genome sequencing [16] |

| Barcoded adapter plates | Multiplexing samples for sequencing | Allows efficient genome sequencing of multiple isolates [16] |

Methodology:

- Sample collection and processing:

- Collect water samples from appropriate depth (epilimnion vs. hypolimnion)

- Process within 24 hours of collection with storage at 4°C

- Pre-filter through 3μm filters to remove larger organisms and particles

Inoculation and incubation:

- Prepare serial dilutions in multiple defined media types

- Dispense into 96-deep-well plates at approximately 1 cell per well

- Incubate at in situ temperatures (16°C for temperate lakes) for 6-8 weeks

- Monitor growth visually and via molecular screening

Molecular screening and isolation:

- Screen using PCR-based methods like plate wash PCR (PWPCR) [12]

- Identify wells containing target taxa via 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Transfer positive cultures to fresh media for purification

- Confirm axenic status by microscopy and repeated molecular analysis

Protocol 2: Metagenome-Guided Targeted Isolation

Methodology:

- Metagenomic analysis:

- Sequence environmental metagenomes from target habitat

- Reconstruct metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) for uncultured taxa

- Analyze metabolic pathways to predict growth requirements [13]

Media design based on genomic predictions:

- Include carbon sources identified in metabolic reconstructions

- Add required vitamins or cofactors based on identified auxotrophies

- Adjust oxygen conditions based on detected respiratory pathways

- Incorporate potential electron donors/acceptors

Targeted isolation:

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting with designed probes

- Apply antibody-based capture for specific cell types

- Use diffusion chambers or in situ devices to simulate natural conditions

Quantitative Context: The Scale of Microbial Diversity

Table: Quantifying the Uncultured Microbial Majority

| Diversity Metric | Value | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated global prokaryotic diversity | 2.2-4.3 million operational taxonomic units | Based on 16S rRNA gene surveys [13] |

| Bacterial phyla with no cultured representatives | 85 phyla | From 194 total phyla in GTDB [10] |

| Cultured vs. validly described species | 24,745 described of 113,104 species clusters | GTDB Release R220 [10] |

| Uncultured genera and phyla in environmental samples | 81% and 25% of microbial cells | Across Earth's microbiomes [13] |

| Success rate with high-throughput dilution-to-extinction | 10 axenic strains per sample (12.6% viability) | Freshwater cultivation study [10] |

The systematic cultivation of previously uncultured microorganisms requires moving beyond traditional methods to embrace integrated approaches that combine genomic insights with refined cultivation techniques. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and methodological frameworks presented in this technical support resource, researchers can significantly advance their ability to bring elusive microbial taxa into culture. Each new cultivated isolate not only expands our understanding of microbial diversity but also provides opportunities for discovering novel metabolic capabilities, ecological interactions, and potentially valuable compounds for biotechnology and medicine. The cultivation tools now available, particularly when guided by genomic data, are progressively dismantling the concept of "uncultivability" that has long limited microbial discovery.

The overwhelming majority of microorganisms in nature have evaded traditional laboratory cultivation, creating a significant bottleneck in the discovery of novel antibiotics and natural products. It is estimated that less than 1% of bacterial diversity can be cultured using standard techniques, leaving over 99% of microorganisms, often referred to as "microbial dark matter," unexplored [17] [4]. This cultivation gap coincides with a critical "discovery void" in antibiotic development; the most recent novel class of antibiotics to reach the market was discovered in 1987 [18] [19] [20]. Overcoming the technical challenges of growing uncultured species is therefore not merely an academic exercise, but a crucial endeavor for accessing new chemical scaffolds to combat the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis [1] [21]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to help researchers access this untapped reservoir of biodiversity.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

Q1: What does it mean for a microorganism to be "unculturable"?

The term "unculturable" is a misnomer; it indicates that current standard laboratory culturing techniques are unable to support the growth of a given bacterium. These organisms are clearly metabolically active and growing in their natural environment, but we lack critical information about their specific biological and nutritional requirements to replicate those conditions in the lab [1]. The inability to cultivate them signifies a gap in our knowledge, not an inherent property of the microbe itself [4].

Q2: Why is accessing uncultured bacteria so critical for new antibiotic discovery?

Historically, natural products from bacteria have been the source of over half of all commercially available pharmaceuticals [1]. The repeated isolation and screening of the same small fraction of culturable bacteria has led to a high rate of compound rediscovery and the collapse of the antibiotic discovery pipeline [1] [22]. It is estimated that to find a new class of antibiotics, more than 10 million isolates from known, culturable bacteria would need to be screened [1]. Accessing the uncultured majority dramatically expands the accessible genetic and metabolic diversity, offering the most promising path to discovering truly novel antibiotic classes [1] [17] [20].

Q3: What are the primary reasons these bacteria fail to grow in the lab?

The simple explanation is a failure to replicate essential aspects of their natural environment. The specific reasons are multifaceted and can include [1] [4]:

- Lack of essential nutrients or growth factors: The standard, nutrient-rich media may be inappropriate for oligotrophic (nutrient-poor environment-adapted) organisms.

- Absence of essential signaling molecules: Some bacteria require chemical signals from other microbes to initiate growth or division.

- Dependence on other organisms (helper strains): Some species rely on helper bacteria to provide specific metabolites, detoxify the environment, or remove oxidative stress.

- Incorrect physicochemical conditions: Factors such as pH, osmotic conditions, temperature, or oxygen tension may not be adequately replicated.

- Inhibition by standard media components: Some ingredients, like agar itself, can be inhibitory to certain microbes [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Cultivation Barriers

This section addresses specific experimental issues and offers solutions based on advanced cultivation strategies.

Table 1: Common Experimental Problems and Advanced Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low recovery of novel isolates; overgrowth by fast-growing lab strains. | Standard media are too rich and selective for fast-growing, common bacteria. | Use low-nutrient media (e.g., 1:10 or 1:100 dilution of R2A); incorporate soil extract (SE) to mimic natural conditions; use gellan gum as an alternative solidifying agent. | [4] |

| Suspected dependence on other microbes or signaling molecules. | The target organism requires growth factors provided by a helper community. | Implement co-culture techniques; use diffusion chambers or bioreactors that allow chemical exchange with a helper community or soil environment. | [1] [4] |

| No growth even after prolonged incubation. | Incubation time is insufficient for slow-growing oligotrophs. | Extend incubation time significantly to 4-8 weeks or longer; protect plates from desiccation during long-term incubation. | [4] |

| Inability to replicate the target organism's natural habitat. | Critical environmental parameters are not being mimicked in the lab. | Employ in situ cultivation using diffusion chambers incubated in the native environment, or use novel bioreactor designs that simulate the natural habitat. | [1] [4] |

| Known high biosynthetic potential from genetic data, but cultivation fails. | The biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) are silent under lab conditions. | Use metagenomics: construct large-insert libraries (e.g., BACs) from environmental DNA (eDNA) and express them in a heterologous host like E. coli or Streptomyces. | [17] [6] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Culturing Uncultured Bacteria

Protocol 1: Diffusion Bioreactor Cultivation

This protocol, adapted from an advanced cultivation study, uses a semi-permeable membrane to maintain cells in their natural chemical environment while allowing for the recovery of pure isolates [4].

1. Bioreactor Design and Setup:

- Construct a double-chambered system with an inner chamber placed inside an outer chamber.

- The inner chamber (e.g., a 2L plastic container) has walls drilled with ~160 holes (6mm diameter) and is covered on the outside with a polycarbonate membrane (0.4 µm pore size).

- Sterilize all components with 70% ethanol, UV light, and rinsing with particle-free water.

- Fill the gap between the inner and outer chamber with fresh, sieved soil from the sampling site.

- Add the soil inoculum (e.g., 3g) and liquid cultivation medium (e.g., 300mL of diluted R2A, R2A-SE, or J26-SE medium) to the inner chamber.

2. Cultivation and Isolation:

- Seal the bioreactor and incubate at room temperature with slow stirring for 4 weeks.

- After incubation, serially dilute the content from the inner chamber and spread onto agar plates of the same medium.

- Incubate the plates aerobically at 25°C for an additional 4 weeks.

- Periodically check for slow-growing microcolonies and purify them through repeated sub-culturing.

This method has been proven successful in cultivating previously uncultured strains by allowing continuous diffusion of essential nutrients and signaling molecules from the natural soil environment [4].

Protocol 2: Function-Based Metagenomic Workflow

This culture-independent protocol bypasses cultivation altogether to access biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) directly from environmental samples [17] [6].

1. Environmental DNA (eDNA) Extraction and Library Construction:

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA directly from the environmental sample (e.g., soil, sediment). Indirect extraction methods that involve physical separation of cells first are preferred to obtain larger DNA fragments.

- Fragment the eDNA and clone it into a * Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) vector* to accommodate large gene clusters (up to 200 kb).

- Transform the constructed library into a heterologous host. While E. coli is common, consider alternative hosts like Streptomyces lividans, Pseudomonas putida, or Ralstonia metallidurans for better expression of genes from phylogenetically distant bacteria [17].

2. Screening for Natural Product Biosynthesis:

- Function-based screening: Screen library clones for desired antimicrobial activity against indicator strains or for specific phenotypes (e.g., pigment production).

- Sequence-based screening: Alternatively, screen the library using next-generation sequencing or PCR for conserved biosynthetic genes like Polyketide Synthases (PKS) and Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS) [17] [6].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this metagenomic approach, showing the two primary screening paths.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Cultivation and Metagenomics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Extract (SE) | A component of culture media to simulate the chemical environment of soil, providing unknown essential nutrients and trace elements. | Prepare from the same habitat as the target inoculum to increase relevance [4]. |

| Gellan Gum | An alternative solidifying agent to agar. | Can prevent the inhibition of growth observed in some fastidious microbes when agar is used [4]. |

| R2A Medium (Diluted) | A low-nutrient medium ideal for isolating slow-growing oligotrophic bacteria from water and soil. | Diluting to 10% or 50% of standard strength can further improve recovery of novel isolates [4]. |

| Diffusion Chamber / Bioreactor | A device that allows chemical exchange between the native environment and the cultivation chamber, mimicking natural habitat. | Can be custom-built or use commercial Transwell plates. Critical for supplying unknown growth factors [1] [4]. |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) Vector | A cloning vector capable of maintaining very large inserts of foreign DNA (100-200 kb), suitable for entire biosynthetic gene clusters. | Essential for function-based metagenomics to capture large operons for natural product synthesis [17]. |

| Heterologous Hosts (e.g., S. lividans) | Expression systems for eDNA libraries. Alternative hosts can improve expression of BGCs compared to the standard E. coli host. | Matching the phylogenetic background of the eDNA and the host can dramatically increase success rates [17]. |

| Resuscitation-Promoting Factor (Rpf) | A bacterial cytokine that stimulates the growth of dormant and recalcitrant bacteria. | Adding Rpf or culture supernatant containing it (e.g., from Micrococcus luteus) can increase microbial diversity in cultures [6]. |

| DL-Tyrosine-d7 | L-4-Hydroxyphenyl-D4-alanine-2,3,3-D3 | L-4-Hydroxyphenyl-D4-alanine-2,3,3-D3 is a deuterated amino acid for metabolic and Parkinson's disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 14-Norpseurotin | 14-Norpseurotin, CAS:1031727-34-0, MF:C21H23NO8, MW:417.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide for Microbial Cultivation

Cultivating environmentally relevant microorganisms, particularly oligotrophs and interdependent species, presents unique challenges. This guide addresses common failure points and provides targeted solutions to bring the "uncultivated microbial majority" into culture [10] [23].

Problem: No Growth or Extremely Slow Growth of Inoculant

Potential Cause & Solution:

Potential Cause Recommended Action Key References / Rationale Inappropriate nutrient concentration (Media is too rich for oligotrophs) [10]. Use low-nutrient media or dilution-to-extinction techniques with defined media that mimic natural substrate concentrations [10] [24]. Rationale: Oligotrophs are inhibited by high nutrient levels. Success was shown using media with 1.1-1.3 mg DOC/L [10]. Insufficient incubation time [24]. Extend incubation periods significantly—weeks or months—instead of days [24]. Rationale: Slow-growing oligotrophs require extended time. Isolates from Antarctic soil appeared after 4-15 weeks [24]. Missing essential growth factors or vitamins [10] [23]. Supplement media with specific growth factors like zincmethylphyrins, short-chain fatty acids, or vitamins based on genomic/metagenomic predictions [23]. Rationale: Many aquatic prokaryotes have reduced genomes with multiple auxotrophies [10].

Problem: Contamination by Fast-Growing Copiotrophs

Potential Cause & Solution:

Potential Cause Recommended Action Key References / Rationale Fast-growing copiotrophs outcompete target slow-growers [10]. Apply high-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation, inoculating at approximately one cell per well to isolate slow-growers from competitors [10]. Rationale: This method physically separates target cells, preventing overgrowth. 627 axenic strains were isolated this way [10]. Inadequate sterilization of equipment or media. Implement rigorous sterilization protocols and work in a sterile environment, ideally with a laminar flow hood [24]. Rationale: Critical for excluding contaminants during long incubations.

Problem: Growth Cessation Upon Subculturing

Potential Cause & Solution:

Potential Cause Recommended Action Key References / Rationale Dependence on other microbes for essential nutrients or detoxification [10] [23]. Employ co-cultivation strategies or use diffusion chambers/iCHIP devices that allow chemical exchange with the native environment [23]. Rationale: Dependencies on co-occurring microbes are common. Co-culture helped isolate Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum [23]. Uncharacterized dependency on signaling molecules. Experiment with conditioned media from environmental samples or known microbial partners. Rationale: Intraspecific and interspecies interactions (e.g., quorum sensing) profoundly affect growth [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective media strategies for isolating oligotrophic microbes? The most successful strategies involve using defined, artificial media with low carbon content (e.g., 1.1-1.3 mg DOC/L) that closely mimics the chemical composition of the natural environment from which the sample was taken. This avoids the inhibition of oligotrophs that occurs on standard nutrient-rich media [10]. Dilution-to-extinction in such media is a highly effective high-throughput method [10].

Q2: How long should I wait for growth to appear before discarding a culture? For many uncultured oligotrophs, incubation periods need to be significantly longer than standard protocols. Viable cultures can appear after 4 weeks, and some may require up to 15 weeks of incubation. Patience and measures to prevent media desiccation are crucial [24].

Q3: My isolated strain grows poorly in liquid media but better on solid surfaces. Why? Some slow-growing environmental bacteria, particularly those with a free-living lifestyle, show a preference for solid surfaces or may form microcolonies that are difficult to disperse in liquid. Continued cultivation on solid media, such as gellan gum-based plates, is often a viable solution [10] [24].

Q4: How can genomic data inform my cultivation strategies? Genome-centric metagenomics and single-cell genomics can reveal metabolic deficiencies (auxotrophies) and potential metabolic pathways of your target organism. This information allows for the rational design of specific cultivation media by supplementing missing vitamins, cofactors, or specific carbon sources that the microbe is predicted to require [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

This protocol is adapted from methods that successfully isolated 627 axenic strains of abundant freshwater bacteria [10].

- Objective: To isolate slow-growing oligotrophic microbes by physically separating them from faster-growing competitors and providing a low-nutrient environment.

- Materials:

- Sterile, defined oligotrophic media (e.g., med2 or med3 from reference [10])

- 96-deep-well plates

- Environmental sample (water, soil suspension)

- Sterile dilution blanks

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Serially dilute the environmental sample in a sterile, dilute saline solution (e.g., 0.9% NaCl) [24].

- Inoculation: Inoculate 96-deep-well plates with a dilution calculated to contain approximately one microbial cell per well [10].

- Incubation: Incubate plates at a temperature relevant to the sample's origin (e.g., 16°C for freshwater lakes) for 6-8 weeks or longer [10].

- Screening: Monitor wells for turbidity. Screen positive wells for purity via 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

- Purification: Transfer cultures from positive wells to fresh defined media to obtain axenic strains.

Protocol 2: Cultivation Using Long Incubation and Low Nutrients

This protocol is effective for isolating rare and slow-growing microorganisms from soil and other solid samples [24].

- Objective: To isolate recalcitrant microorganisms by simulating low-nutrient conditions and allowing for extremely slow growth rates.

- Materials:

- Low-nutrient media (e.g., 1/100 diluted Nutrient Broth, ~0.08 g/L) [24]

- Gellan gum (as a solidifying agent)

- MgSO₄·7H₂O

- Procedure:

- Media Preparation: Prepare 1/100 diluted Nutrient Broth, solidified with 0.7% gellan gum. Add 0.1% MgSO₄·7H₂O to promote solidification [24].

- Plating: Spread plate serial dilutions of the soil suspension onto the prepared media.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at a low temperature (e.g., 12°C) in sealed polyethylene bags to prevent desiccation for up to 15 weeks [24].

- Selection: Weekly, use a stereo microscope to identify and mark new, morphologically distinct colonies that appear after 4 weeks of incubation.

- Isolation: Pick and streak these late-appearing colonies onto fresh plates of the same low-nutrient media to obtain pure isolates.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical troubleshooting workflow for addressing microbial cultivation failures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for advanced cultivation of uncultured microbes.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Defined Oligotrophic Media (e.g., med2/med3 [10]) | Provides a reproducible, low-nutrient environment that mimics natural conditions to avoid inhibiting oligotrophs. |

| Gellan Gum | A superior solidifying agent for plates, often preferred over agar for the growth of certain environmental microbes [24]. |

| Diffusion Chambers / iCHIP [23] | Devices that allow microbes to be cultivated in situ by permitting the diffusion of environmental nutrients and signals. |

| Specific Growth Factors (e.g., vitamins, short-chain fatty acids, coproporphyrins [23]) | Supplements to address auxotrophies predicted by genomic analysis or suspected in fastidious microbes. |

| Selective Inhibitors (e.g., diuron [23]) | Used to suppress the growth of oxygenic phototrophs or other competing microorganisms in enrichment cultures. |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryldithio-CoA | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryldithio-CoA, CAS:134785-93-6, MF:C27H44N7O20P3S2, MW:943.7 g/mol |

| 3-Hydroxystearic acid | 3-Hydroxystearic acid, CAS:45261-96-9, MF:C18H36O3, MW:300.5 g/mol |

Cultivation Breakthroughs: From Simulated Environments to High-Throughput Technologies

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

This guide addresses specific, frequently encountered problems when performing dilution-to-extinction cultivation, helping to ensure the successful isolation of previously unculturable species.

Table: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

| Problem | Probable Cause | Recommended Solution | Prevention Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| No bacterial growth in wells after incubation [25] | Over-dilution of the bacterial suspension. | Reduce the dilution factor or increase the starting inoculum concentration [25]. | Perform a pilot test to determine the optimal dilution for your sample. |

| Excessive growth in all wells [25] | Bacterial concentration in the dilution series is too high. | Prepare a more diluted suspension before plating to optimize for microbial diversity [25]. | Use cell counting (e.g., flow cytometry) to standardize the initial inoculum [10]. |

| Cross-contamination between wells [25] | Splashing during pipetting. | Use slow and controlled pipetting; centrifuge the plate before pipetting to minimize splashing [25]. | Work in a laminar flow hood and use filter tips. |

| Drying of liquid medium in outer wells [25] | Incomplete sealing of microplates. | Ensure plates are tightly sealed with Parafilm, paying special attention to the edges [25]. | Use plates with low-evaporation lids and incubate in a humidified chamber. |

| No visible PCR product [25] | PCR inhibitors from the sample or degraded DNA. | Dilute the DNA template 1:10 or purify it using a cleanup kit [25]. Avoid overheating during alkaline lysis [25]. | Include a positive control in the PCR reaction. |

| Low recovery rate after freezing [25] | Sensitivity to freeze-thaw process; insufficient cryoprotectant mixing. | Increase bacterial concentration in glycerol stocks; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [25]. | Ensure glycerol and bacterial culture are thoroughly mixed before storage at -80°C [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core principle behind dilution-to-extinction cultivation, and why is it effective for "unculturable" species?

Dilution-to-extinction involves progressively diluting a microbial sample in a growth medium until, theoretically, only a single cell remains in some of the wells [26]. This method is effective for isolating rare and slow-growing bacteria for two main reasons. First, it physically separates cells, preventing fast-growing "weeds" from outcompeting slow-growing or rare taxa [25] [27]. Second, it allows researchers to use very low-nutrient defined media that mimic a microbe's natural oligotrophic environment, which is often essential for the growth of many environmentally relevant microbes that are inhibited by standard rich media [10] [28].

2. How do I choose between a defined medium and a natural medium like autoclaved lake water?

Both approaches have merits. Defined artificial media are preferred for reproducibility and for systematically determining the specific nutritional requirements of an isolate [10]. They allow for precise control over every component. Natural media (e.g., filter-sterilized lake or seawater) can be highly effective as they inherently contain the natural mix of nutrients and trace elements from the environment [29]. However, their composition can vary seasonally, and sterilization can degrade heat-sensitive compounds [10]. A modern strategy is to create defined media that chemically mimic natural conditions, often containing µM concentrations of carbon sources, vitamins, and other organic compounds [10].

3. Our team successfully isolated a novel bacterium using this method, but it grows very slowly. How can we improve its growth?

Slow growth is a common characteristic of many oligotrophic isolates [10]. To improve growth, consider:

- Co-cultivation: Some bacteria depend on other microbes for essential nutrients or detoxification of metabolites [1] [10]. Try growing your isolate with a helper strain from the same environment.

- Supplementation: Add small amounts of catalase to degrade toxic reactive oxygen species, which has been key to cultivating groups like the freshwater acI Actinobacteria [30]. Other supplements like resuscitation-promoting factor (Rpf) can also stimulate growth [6].

- Patience: Ensure your incubation times are sufficiently long (weeks to months) and avoid frequent sub-culturing, which can stress slow-growing organisms [1].

4. Our sequencing results show low-quality reads or unequal depth across samples. What went wrong?

This is often a problem with the PCR step prior to sequencing. Low-quality reads can result from poor primer specificity or degraded PCR products [25]. To fix this, use a high-fidelity polymerase and verify your primer design. Unequal sequencing depth is typically caused by uneven concentrations of PCR products before pooling [25]. Always double-check and normalize PCR product concentrations to ensure an even representation of all samples [25].

5. What are the major limitations of high-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation?

While powerful, this method has inherent biases:

- Liquid Medium Bias: It preferentially isolates microbes that grow well in liquid, potentially missing those that require solid surfaces for biofilm formation [25].

- Aerobic Bias: The protocol is typically designed for aerobic conditions and will miss obligate anaerobes without modification [25].

- Loss of Interdependent Microbes: The method isolates individual cells, disrupting syntrophic or symbiotic relationships essential for some species [25] [1].

- Medium Selectivity: The choice of medium (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth) will favor certain groups while excluding oligotrophs or extremophiles that require specialized nutrients [25] [28].

Experimental Workflow and Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a high-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation experiment, from sample preparation to the generation of a culture collection.

Core Protocol Steps:

- Sample Collection & Preparation: Fresh environmental samples (e.g., plant roots, lake water) are collected and processed to create a homogeneous cell suspension in a buffer like sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [25] [27].

- Serial Dilution & Dispensing: The cell suspension is subjected to a series of dilutions in a defined, low-nutrient culture medium. The diluted suspension is then dispensed into the wells of 96-well plates, with a theoretical dilution aiming for one cell per well [25] [10].

- Incubation: Plates are sealed to prevent evaporation and incubated for extended periods (from several weeks to months) at a temperature reflective of the natural environment [27] [10]. This allows slow-growing oligotrophs to proliferate.

- Growth Screening & Purification: Wells are visually inspected for turbidity, indicating microbial growth [27]. Positive wells are transferred to fresh medium to ensure purity and robust growth. Purity is confirmed via microscopy and sequencing.

- Identification & Preservation: Isolates are identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and pure cultures are preserved in glycerol stocks at -80°C for long-term storage and future studies [25] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Reagents for Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation with Defined Media

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Oligotrophic Media | Simulates natural nutrient conditions to grow bacteria adapted to low nutrient availability (oligotrophs) [10]. | Artificial freshwater media (e.g., med2, med3) with µM concentrations of carbon sources, vitamins, and organic compounds [10]. |

| Catalase | Degrades toxic hydrogen peroxide, a common stressor in vitro. Crucial for isolating sensitive taxa. | Supplementation was key to cultivating previously uncultured acI lineage Actinobacteria from a lake [30]. |

| Resuscitation-Promoting Factor (Rpf) | A bacterial growth factor that stimulates the resuscitation of dormant cells from a viable but non-culturable state. | Micrococcus luteus culture supernatant containing Rpf increased the diversity of cultured bacteria from soil [6]. |

| Complex Natural Carbon Sources | Provides a diverse mixture of organic compounds to support the growth of bacteria with unknown or complex nutritional needs. | Sediment dissolved organic matter (DOM) and bacterial cell lysate were far more effective than simple sugars in cultivating diverse subsurface microbes [28]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Tools | Enables efficient processing of thousands of cultures. | Use of 96-well deep-well plates, automated liquid handling, and flow cytometry for growth screening [25] [29]. |

| Magnetic Beads for DNA Clean-up | Purifies PCR products by removing contaminants and enzymes, essential for high-quality sequencing library preparation. | Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS magnetic beads used to clean up PCR products before sequencing [25]. |

| 2'-Deoxy-NAD+ | 2'-Deoxy-NAD+, CAS:151411-04-0, MF:C21H28N7O14P2+, MW:664.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Quifenadine hydrochloride | Quifenadine Hydrochloride|CAS 10447-38-8|H1 Blocker |

The pursuit of cultivating the "unculturable" represents one of the most significant challenges in modern microbiology. The vast majority of microbial species on Earth resist growth under standard laboratory conditions, creating a substantial gap in our understanding of microbial diversity and its potential applications [1]. This technical support center is designed to equip researchers with practical methodologies for employing advanced in-situ cultivation techniques, specifically diffusion chambers and semi-permeable capsules. These approaches bridge the gap between the laboratory and the natural environment, allowing researchers to cultivate previously inaccessible microorganisms for drug discovery, ecological studies, and fundamental biological research [4] [31].

Key Experimental Protocols

Diffusion Bioreactor Assembly and Workflow

The diffusion bioreactor technique enables environmental nutrients and signalling molecules to reach encapsulated microorganisms, mimicking their natural habitat.

Detailed Methodology [4]:

- Chamber Construction: The system consists of two chambers. The inner chamber is a 2-L plastic container (approximately 140 mm wide × 150 mm tall). The outer chamber is a larger 4-L plastic container (approximately 240 mm wide × 120 mm tall).

- Membrane Preparation: Create approximately 160 holes (6 mm diameter) in the walls of the inner chamber. Affix a sterile polycarbonate membrane with a 0.4 µm pore size to the outer side of this chamber. This membrane allows for the diffusion of molecules while containing the cells.

- Sterilization: Sterilize all components with 70% ethanol, air-dry under UV light in a laminar flow hood for 24 hours, and perform a final rinse with particle-free molecular grade water.

- System Setup:

- Place the prepared inner chamber inside the outer chamber.

- Fill the gap between the two chambers with freshly collected and sieved environmental soil (e.g., forest soil) to recreate the natural chemical environment.

- Inside the inner chamber, add 3 grams of the soil sample to be cultured into 300 mL of a selected culture medium.

- Seal the inner chamber lid tightly with sealing tape.

- Incubation and Recovery: Incubate the entire bioreactor assembly at room temperature for up to 4 weeks with gentle stirring. After incubation, serially dilute the contents of the inner chamber, plate onto solid agar media, and incubate aerobically at 25°C for another 4 weeks to obtain pure isolates.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

Microencapsulation and In-Situ Incubation

This protocol uses agarose microbeads to encapsulate single cells or micro-colonies, protecting them and allowing for high-throughput analysis while exposed to their native environment.

Detailed Methodology [31]:

- Sample Preparation: Dislodge bacteria from the environmental sample (e.g., marine sediment). Wash the sediment with a diluted nutrient broth (e.g., 1:10 Marine Broth) to remove salts and debris. Concentrate the bacterial cells via centrifugation.

- Cell Encapsulation:

- Resuspend the concentrated cells in 1% (w/v) Low Gelling Temperature (LGT) agarose, prepared in a diluted culture medium and maintained at 35°C.

- Use a microfluidic chip to generate microbeads with a diameter of 80 ± 20 µm, containing the encapsulated bacteria.

- Dialysis Cassette In-Situ Incubation:

- Load the agarose microbeads (or a non-encapsulated cell resuspension for comparison) into a modified dialysis cassette (e.g., a Slyde-A-Lyzer cassette).

- Seal the cassette and incubate it in the original natural environment (e.g., submerged in the source marine water) for one week. This allows for continuous diffusion of environmental compounds.

- Laboratory Cultivation: After the in-situ incubation, retrieve the cassette. Plate the contents (either the microbeads or the liquid suspension) onto solid culture media and incubate under appropriate laboratory conditions to recover isolates.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Recovery of Novel Isolates

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low diversity of recovered colonies; predominantly fast-growing, common species. | Nutrient-rich media favor fast-growing bacteria and inhibit oligotrophic (nutrient-preferring) species [1]. | Use low-nutrient media such as 50% diluted R2A, or media supplemented with soil extract (SE) or habitat-specific extracts [4]. |

| Incubation time is too short for slow-growing species to form visible colonies [4]. | Extend incubation periods significantly, up to several weeks or months [4]. | |

| Missing essential growth factors or signaling molecules provided by other microbes in the natural community [1]. | Employ co-culture techniques with "helper" strains from the same environment, or use diffusion systems that allow exchange of metabolites [1]. |

Contamination and System Integrity

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Growth of contaminants (e.g., mold, common lab bacteria) in the inner chamber or capsules. | Compromised membrane or seal, allowing invasive cells to enter [32]. | Prior to use, perform an overpressure test on assembled chambers to check for leaks. Replace O-rings and seals regularly [32]. |

| Contaminated inoculum or laboratory media [32]. | Check the sterility of the inoculum by plating a sample on a rich medium. Ensure all media and reagents are properly sterilized [32]. | |

| Contamination introduced during the assembly process. | Pre-assemble as many components as possible before sterilization. Minimize connections made after autoclaving [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main advantage of using an in-situ diffusion chamber over traditional lab plates? A1: Diffusion chambers and capsules allow microorganisms to be exposed to the natural chemical and physical gradients of their original habitat, including nutrients, signaling molecules, and metabolic byproducts from neighboring organisms. This simulated natural environment provides essential growth conditions that are impossible to replicate with synthetic media in a petri dish, enabling the cultivation of previously "unculturable" species [1] [4].

Q2: How does the pore size of the membrane affect the experiment? A2: The membrane must have a pore size small enough to physically contain the bacterial cells (typically 0.4 µm or smaller) but large enough to allow the free diffusion of nutrients, dissolved gases, and other critical small molecules from the external environment into the chamber [4].

Q3: We are not recovering any growth after retrieval. What could be wrong? A3: First, verify that your sterilization process (e.g., autoclaving) reached the correct temperature and time, and that steam could penetrate all parts of the equipment [32]. Second, ensure the membrane is not clogged with soil particles, which would prevent diffusion. Third, consider extending the in-situ incubation period, as some slow-growing species may require more time to initiate replication [4].

Q4: Can these techniques be used for anaerobic microorganisms? A4: Yes, the principle is adaptable. The system must be assembled and incubated in an anaerobic environment to ensure that oxygen does not diffuse through the membrane and into the chamber. This typically requires the use of an anaerobic chamber for setup and placement in an anoxic environment for incubation [33].

Data Presentation: Optimizing Recovery

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from a key study that utilized a diffusion bioreactor for cultivating soil bacteria, highlighting the impact of critical experimental parameters [4].

Table 1: Impact of Experimental Parameters on Bacterial Recovery from Forest Soil Using a Diffusion Bioreactor [4]

| Parameter | Condition Tested | Key Finding on Recovery |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivation Technique | Novel Diffusion Bioreactor | Successfully cultivated 35 previously uncultured strains. |

| Traditional Shake Flask/Plating | No previously uncultured strains were recovered. | |

| Sampling Season | Summer (e.g., July, August) | Increased recovery of uncultured and novel isolates. |

| Winter (e.g., February, January) | Lower recovery of novel diversity. | |

| Incubation Period | Prolonged (up to 4 weeks) | Critical for the recovery of slow-growing species. |

| Culture Media | Low-substrate (e.g., 50% R2A, R2A-SE) | Enhanced recovery of novel and uncultured isolates. |

| Nutrient-rich (e.g., TSA, LB) | Favored fast-growing, commonly cultured species. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for In-Situ Cultivation Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Permeable Membrane | Forms a physical barrier that permits diffusion of molecules but contains cells. | Polycarbonate membrane (0.4 µm pore size) [4]. |

| Low-Gelling Temperature Agarose | Used for microencapsulation of cells; gels at low temperatures to maintain cell viability [31]. | Sigma A9414, prepared in diluted culture medium at 35°C [31]. |

| Dialysis Cassette | Serves as a ready-made, robust diffusion chamber for in-situ incubation. | Modified Slyde-A-Lyzer cassettes [31]. |

| Culture Media | Provides basal nutrients for growth. Low-nutrient media are often superior. | R2A, 50% Diluted R2A, Soil Extract (SE)-supplemented media [4]. |

| Soil Extract (SE) | Adds habitat-specific nutrients and trace elements that may be critical for growth of fastidious organisms [4]. | Prepared by centrifuging and filter-sterilizing an aqueous soil slurry. |

| Cycloheximide | An antifungal agent to suppress fungal contamination in bacterial cultures. | Used at 50 µg/mL in culture media [4]. |

| N-Boc-Tris | N-Boc-Tris, CAS:146651-71-0, MF:C9H19NO5, MW:221.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Triammonium phosphate trihydrate | Triammonium phosphate trihydrate, CAS:25447-33-0, MF:H18N3O7P, MW:203.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technique Selection and Workflow

Choosing the right technique and understanding the microbial responses to their environment are crucial for success. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for technique selection and the biological principles underlying in-situ cultivation.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the population ratio in my synthetic consortium unstable over time? The instability often arises from competitive or antagonistic relationships between member species, where faster-growing microbes outcompete others for limited resources like phosphate and nitrogen, even in nutrient-rich environments [34] [35]. This "winner-takes-all" dynamic can collapse the intended community structure. To mitigate this, design cross-feeding dependencies or allocate different carbon sources to different species to reduce direct competition [35].

Q2: How can I determine the interaction types between species in my consortium? Computational modeling tools like the generalized Lotka-Volterra (gLV) model can predict interaction types and their impact on community diversity [34] [36]. Furthermore, Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) can model temporal metabolic exchanges and emergent interactions during community assembly [34]. These tools provide mechanistic insights into the ecological relationships within your consortium.

Q3: What should I do if my coculture shows reduced overall biomass or product yield? Reduced yield can result from metabolic imbalances or competitive interactions that suppress the growth of individual members compared to their monoculture performance [34] [35]. Establish mutualistic cross-feeding interactions, for example, by engineering co-dependence on exchanged metabolites like amino acids or vitamins, to shift the relationship toward symbiosis and enhance system stability and output [35].

Q4: How does the initial inoculation ratio affect the final community structure? Research on a model three-member rhizosphere community found that different initial inoculum ratios (varying by up to three orders of magnitude) did not significantly alter the final community structure or the competitive interaction patterns [34]. The community consistently reached the same stable composition, suggesting that in some systems, emergent interactions rather than initial conditions dictate the final outcome.

Troubleshooting Common Coculture Problems

Problem: Rapid Overgrowth by One consortium Member

- Potential Causes: Direct competition for a primary nutrient source (e.g., glucose, phosphate); lack of growth-inhibiting interactions toward the dominant member [35].

- Solutions:

- Resource Partitioning: Genetically engineer members to utilize different carbon substrates. For example, knock out glucose transporter genes in one strain to force the use of another carbon source like xylose [35].

- Establish Cross-Feeding: Design the system so that the overgrown member relies on a metabolite provided by another member, creating a mutualistic check on its population [35].

Problem: Low Product Titer Despite Good Cell Growth

- Potential Causes: Metabolic burden; inefficient metabolite transfer between members leading to dilution in the extracellular environment [35].

- Solutions:

- Spatial Engineering: Use materials or biofilms to spatially organize the members, potentially reducing diffusion distances and improving metabolic exchange efficiency [37].

- Pathway Optimization: Rebalance the metabolic flux by adjusting gene expression levels in the different members to minimize the accumulation of inhibitory intermediates [35].

Problem: Consortium Fails to Stabilize After Serial Transfer

- Potential Causes: Antagonistic interactions, such as one member producing inhibitory compounds; lack of essential cross-feeding metabolites [35].

- Solutions:

- Screen for Compatibility: Before final assembly, test all pairwise interactions to identify and replace strains that exhibit strong antagonism [35].

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Coculture the members over multiple generations to allow for the evolution of stable, cooperative interactions, as demonstrated in systems where vitamin-producers were evolved to support vitamin-dependent yeast [35].

Summarized Experimental Data

Table 1: Population Dynamics in a Model Three-Member Bacterial Community in Nutrient-Rich Medium [34]

| Bacterial Strain | Relative Abundance in Stabilized Community (Plate Count) | Relative Abundance in Stabilized Community (qPCR) | Growth in Coculture vs. Monoculture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. GM17 | Dominant (Majority) | Dominant (Majority) | Significantly decreased |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Intermediate | Higher than plate count | No significant difference (plate count) / Decreased (qPCR) |

| Sphingobium sp. AP49 | Low | Low | Decreased by ~two orders of magnitude |

Table 2: Computational Tools for Modeling and Designing Microbial Consortia [34] [36]

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Lotka-Volterra (gLV) | Ecological Model | Predicts interaction types (e.g., competition, cooperation) between species and their effect on community diversity. | Analyzing succession and stability in a three-strain rhizosphere community [34]. |

| Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) | Metabolic Model | Models time-dependent microbial growth and metabolite-mediated interactions using genome-scale metabolic models. | Predicting temporal metabolic exchanges during community assembly [34]. |

| COMETS (Computation of Microbial Ecosystems in Time and Space) | Software Platform (extends dFBA) | Simulates spatiotemporal dynamics and metabolic interactions of microbial communities. | Providing mechanistic insight into community structure emergence [34]. |

| Treg Induction Score (TrIS) | Computational Index | Scores and ranks microbial consortia by their predicted potential to induce a specific immune response (e.g., Treg cells). | Selecting optimal Clostridia consortia for immune modulation in mice [36]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing and Tracking a Synthetic Microbial Community

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the formation of stabilized communities in nutrient-rich conditions [34].

1.1 Bacterial Strains and Medium

- Strains: Pseudomonas sp. GM17, Pantoea sp. YR343, and Sphingobium sp. AP49 (or your chosen isolates).

- Medium: R2A complex medium (or another nutrient-rich medium relevant to the isolation environment).

1.2 Inoculation and Serial Transfer

- Prepare the initial co-culture by inoculating the three strains in R2A medium at the desired initial ratio (e.g., 1:1:1, or varied for testing priority effects).

- Incubate at an appropriate temperature (e.g., 30°C) with shaking for 24 hours (or one growth cycle).

- After the growth cycle, serially transfer the community by diluting an aliquot (e.g., 1:100) into fresh R2A medium.

- Repeat this transfer for multiple cycles (e.g., 5-10 cycles) to allow the community to stabilize.

1.3 Tracking Community Structure

- Plate Counting: At each transfer time point, serially dilute the culture and spread plate on solid R2A agar. Identify and count the different species based on colony morphology.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): As a complementary and often more precise method, extract total DNA from the community at each time point. Perform qPCR using strain-specific primers to quantify the abundance of each member. Calculate the relative percentage of each species.

1.4 Data Analysis

- Plot the relative abundance of each species over time for both plate counting and qPCR data to visualize community succession and stabilization.

- Compare the final abundance of each species in coculture to its maximum abundance in monoculture to infer interaction types (e.g., competition if growth is decreased).

Protocol 2: Computational Simulation of Community Dynamics using gLV

This protocol outlines how to use the gLV model to predict microbial interactions [34] [36].

2.1 Model Formulation The generalized Lotka-Volterra model for multiple species is defined by the equation:

( \frac{dXi}{dt} = \mui Xi \left(1 - \frac{\sum{j=1}^n \alpha{ij} Xj}{K_i}\right) )

Where:

- ( X_i ) is the biomass (or abundance) of species ( i ).

- ( \mu_i ) is the intrinsic growth rate of species ( i ).

- ( K_i ) is the carrying capacity of species ( i ).

- ( \alpha_{ij} ) is the interaction coefficient, representing the effect of species ( j ) on species ( i ).

2.2 Parameterization

- Monoculture Data: Grow each species in monoculture to estimate its intrinsic growth rate (( \mui )) and carrying capacity (( Ki )).

- Interaction Terms (( \alpha_{ij} )): Estimate the interaction coefficients by fitting the gLV model to time-series data of all species in coculture. This can be done using nonlinear regression or other model-fitting algorithms.

2.3 Simulation and Prediction

- Use the parameterized gLV model to simulate the population dynamics of the community over time from different starting conditions.

- Validate the model by comparing its predictions with experimental data not used in the fitting process (e.g., from different initial inoculum ratios).

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Coculture Development Workflow

Microbial Interaction Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Microbial Consortium Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| R2A Complex Medium | A nutrient-rich medium suitable for cultivating a wide range of environmental bacteria, mimicking resource-abundant environments like the rhizosphere [34]. | Serving as the growth medium to study community assembly without obligate metabolic dependencies [34]. |

| Strain-Specific qPCR Primers | Enable precise quantification of individual species' abundance within a mixed community, bypassing limitations of morphology-based colony counting [34]. | Tracking the population dynamics of each consortium member over serial transfer cycles [34]. |

| COMETS Software Platform | A powerful bioinformatics tool that performs dFBA simulations to predict spatiotemporal metabolic interactions in microbial communities [34]. | Modeling and predicting metabolite exchanges and emergent interactions during consortium stabilization [34]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Critical for routine quality control to detect mycoplasma contamination, which can alter cell metabolism and gene expression without obvious visual signs [38] [39]. | Ensuring that mammalian cell cocultures or host-interaction experiments are not compromised by underlying contamination [40]. |

| Antibiotics for Selection | Used to maintain plasmid stability or select for specific engineered strains within a consortium. Use with caution to avoid inducing gene expression changes [38]. | Maintaining a desired population ratio in a consortium of engineered strains, each with different antibiotic resistance markers. |

| 9-Fluorenylmethanol | 9-Fluorenemethanol, 99%|CAS 24324-17-2|RUO | 9-Fluorenemethanol, a key synthetic intermediate for Fmoc peptide chemistry. ≥98% purity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers tackling the challenge of cultivating previously uncultured microorganisms. The following troubleshooting guides and FAQs address common experimental hurdles in using genomic data to design custom growth media, supporting broader efforts in microbial cultivation for drug discovery and environmental research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Targeted Isolation Challenges

Problem 1: Poor or No Growth Despite Genomic Evidence of Metabolic Potential

Question: My microorganism's genome suggests all necessary metabolic pathways are present, but I'm not observing growth in my designed medium. What could be wrong?

Answer: This common issue often stems from mismatches between genomic potential and actual cultivation requirements. Try these solutions:

- Verify nutrient concentrations: Genomic evidence often indicates trophic strategy. For genome-streamlined oligotrophs, reduce carbon content to 1-2 mg DOC per liter, as high nutrient levels can inhibit growth [10].

- Check for auxotrophies: Look for missing biosynthetic pathways in the genome that suggest dependencies on specific growth factors. Supplement with yeast extract (0.001-0.01%) or a vitamin mixture to cover potential gaps [10].

- Recreate environmental conditions: If the source environment data is available, match pH, temperature, and ionic composition. For freshwater oligotrophs, successful cultivation often occurs at 16°C with μM concentrations of organic compounds [10].

- Extended incubation: Slowly growing oligotrophs may require 6-8 weeks before visible growth appears [10].

Problem 2: Contamination Outcompetes Target Organism

Question: My custom media supports growth, but fast-growing contaminants overwhelm my target microorganism. How can I address this?

Answer: This typically occurs when media conditions favor copiotrophs over your target organism:

- Apply dilution-to-extinction: Inoculate multiple wells with approximately one cell per well to separate target organisms from competitors [10].

- Reduce nutrient levels: Switch to low-nutrient defined media that specifically disadvantages fast-growing copiotrophs [10].

- Use semi-permeable membranes: Cultivate cells in diffusion chambers that allow nutrient exchange while providing physical separation [1].

- Add resuscitation factors: Supplement with Micrococcus luteus culture supernatant containing resuscitation-promoting factor (Rpf) to stimulate dormant cells [6].

Problem 3: Growth Initiates but Cannot Be Sustained

Question: I observe initial growth in primary cultivation, but the culture cannot be maintained through transfers. What might be causing this?

Answer: This suggests missing factors in your transfer media:

- Identify essential cofactors: Genomic analysis may reveal dependencies on specific metabolites. Test additions of catalase, various vitamins, or specific carbon sources [10].

- Check for metabolic byproduct dependencies: Some microorganisms require metabolites produced by other bacteria. Consider co-culture with suspected partner organisms [1].