Clearing the Static: A Comprehensive Guide to Noise Reduction in Microbial Community Data Analysis

Microbiome data is inherently noisy, presenting significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to derive robust biological insights.

Clearing the Static: A Comprehensive Guide to Noise Reduction in Microbial Community Data Analysis

Abstract

Microbiome data is inherently noisy, presenting significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to derive robust biological insights. This article provides a comprehensive guide to navigating and mitigating these challenges, from foundational concepts to advanced computational techniques. We first explore the core sources of noise, including technical artifacts, contamination, and data sparsity. We then detail a suite of methodological solutions, covering experimental design, computational decontamination, and advanced deep learning models like denoising diffusion processes. The guide further offers practical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing analyses in challenging scenarios like low-biomass studies and provides a framework for validating findings through synthetic data benchmarks and rigorous comparative analysis. By synthesizing these approaches, this resource aims to empower researchers to achieve higher data fidelity, leading to more reliable and reproducible results in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Signal: Defining Noise and Its Sources in Microbiome Data

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Failed PCR in Microbiome Studies

1. Identify the Problem The problem is a failed PCR reaction, characterized by no visible product on an agarose gel despite the DNA ladder being present [1].

2. List All Possible Explanations Possible causes include issues with any component of the PCR Master Mix: Taq DNA Polymerase, MgCl2, Buffer, dNTPs, primers, or the DNA template. Also consider equipment and procedural errors [1].

3. Collect the Data

- Controls: Check if a positive control (e.g., using a known DNA vector) produced a product [1].

- Storage and Conditions: Verify the expiration date and storage conditions of the PCR kit [1].

- Procedure: Review your laboratory notebook against the manufacturer's instructions for any modifications or missed steps [1].

4. Eliminate Explanations If the positive control worked and the kit was valid and properly stored, eliminate the kit and procedure as causes [1].

5. Check with Experimentation Test remaining potential causes. For example, run the DNA samples on a gel to check for degradation and measure DNA concentration to confirm sufficient template was used [1].

6. Identify the Cause After experimentation, the cause can be identified (e.g., degraded DNA or low DNA concentration). Plan to fix the issue, such as using a premade master mix to reduce future errors [1].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting High Variability in Cell Viability Assays

1. Identify the Problem The problem is a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT assay) showing unexpectedly high error bars and high variability in results [2].

2. List All Possible Explanations Consider causes related to assay controls, specific cell line culturing conditions (e.g., dual adherent/non-adherent lines), and technical procedures during wash steps [2].

3. Collect the Data

- Controls: Verify that appropriate negative controls (e.g., a cytotoxic compound with a range of behavior) were included [2].

- Procedure: Examine the detailed protocol, focusing on steps like aspiration during washes [2].

4. Eliminate Explanations If controls are correct, focus on procedural techniques.

5. Check with Experimentation Propose an experiment to modify the technique, such as carefully aspirating supernatant with a pipette on the well wall and tilting the plate, while examining cell density after each step. Run this with both a negative control and the test sample [2].

6. Identify the Cause The source of error is often user-generated, such as inconsistent aspiration during washes leading to uneven cell loss. Proper technique should resolve the high variability [2].

Guide 3: Investigating Potential Microbial Contamination in Analogue Habitats

1. Identify the Problem The goal is to determine if human-associated microbes from inside a habitat (e.g., a Mars analogue station) have contaminated the external environment [3].

2. List All Possible Explanations

- Forward contamination (interior microbes leaking out).

- Backwards contamination (environmental microbes brought inside).

- Cross-contamination from sampling procedures [3].

3. Collect the Data

- Sampling: Collect duplicate swab samples from high-touch interior surfaces (e.g., door handles, keyboards) and triplicate soil samples from the immediate exterior. Use sterile swab kits and PBS [3].

- DNA Analysis: Perform DNA extraction and sequence target genes (e.g., bacterial 16S rRNA, fungal ITS1). Include a negative control (PBS and an unexposed swab) to identify any kit or reagent contaminants ("kitome") [3].

- Bioinformatics: Process sequencing data using a standardized pipeline like QIIME2 [3].

4. Eliminate Explanations

- Control Analysis: The negative control identifies contaminant DNA present in reagents.

- Statistical Analysis: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) to see if soil samples cluster separately from interior swabs [3].

5. Interpret Results

- No Forward Contamination: If PCA shows no significant shared ASVs between interior and soil samples, and the soil microbiome is characterized by typical environmental taxa (e.g., Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota), forward contamination is not detected [3].

- Evidence of Backwards Contamination: If bacterial genera not typically human-associated (e.g., Paracoccus, Cesiribacter, Psychrobacter) are found in both soil and interior swabs, this suggests environmental microbes were brought inside [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between technical and biological replicates?

- Technical Replicates are repeated measurements of the same sample. They assess the reproducibility and variability of the assay or technique itself but do not address biological relevance [4].

- Biological Replicates are measurements taken from biologically distinct samples (e.g., from different organisms, different batches of independently cultured cells). They capture random biological variation and indicate how widely an experimental effect can be generalized [4].

Q2: What are the key alpha diversity metrics I should report for microbiome data? A comprehensive analysis should include metrics from these core categories [5]:

| Category | Key Metrics | What it Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Richness | Chao1, ACE, Observed ASVs | Number of distinct species or taxa in a sample [5]. |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Faith's PD | Evolutionary history encompassed by all species in a sample [5]. |

| Information | Shannon, Brillouin | Combines richness and evenness of species abundances [5]. |

| Dominance/Evenness | Simpson, Berger-Parker, ENSPIE | How evenly abundances are distributed among species; dominance of the most abundant taxon [5]. |

Q3: How can I determine if my microbiome samples have been cross-contaminated?

- Sequencing Controls: Always include and sequence negative extraction controls (blanks) to identify contaminant DNA from reagents or kits ("kitome") [3].

- Community Analysis: Look for taxa in your samples that are known laboratory or reagent contaminants. The presence of these in your blanks but not your samples indicates potential cross-contamination [3].

- Source Tracking: Use statistical methods to compare the microbial profiles of your samples with potential contaminant sources [3].

Q4: My negative control in a PCR-based assay is showing a positive result. What should I do? This is a classic sign of contamination. Follow a systematic approach [1]:

- List Explanations: Contaminated water/PBS, contaminated primers, contaminated master mix, aerosol contamination from positive samples, or contaminated DNA template [1].

- Test Systematically: Test each component of your reaction with a fresh, unopened aliquot if possible. Include a "water-only" control (no template) to pinpoint the source.

- Decontaminate: Clean workspaces and equipment with UV light or DNA-degrading solutions. Use dedicated pipettes and filter tips for PCR setup [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sampling and Analyzing Microbiomes for Contamination Studies

1. Sample Collection [3]

- Interior Surfaces: Using sterile swab kits (e.g., FloqSwabs) moistened with sterile PBS, swab a defined area (e.g., 10x10 cm) of high-touch surfaces. Swab in multiple directions.

- Exterior Soil: Using ethanol-sterilized gloves, collect soil into sterile 50 mL Falcon tubes.

- Storage: Refrigerate samples at 4°C immediately after collection, then transfer to -80°C for long-term storage.

2. DNA Extraction [3]

- Swab Processing: Add PBS to the swab container, agitate, centrifuge, and use the pellet with a DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit).

- Soil Processing: Use a high-yield soil DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit).

- Quality Control: Check DNA concentration and quality.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing [3]

- Target Amplicons: Amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4 region), the archaeal 16S rRNA gene, and the fungal ITS1 region.

- Sequencing: Perform on a platform such as Illumina MiSeq.

4. Bioinformatic Analysis [3]

- Processing: Use QIIME2 to demultiplex sequences, perform quality control, cluster into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), and assign taxonomy.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on ASV tables to visualize sample similarity/dissimilarity.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Sterile Swab Kits (e.g., FloqSwabs) | For standardized and sterile collection of microbes from surfaces [3]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | For effective DNA extraction from swab pellets and other low-biomass samples, inhibiting PCR inhibitors often found in environmental samples [3]. |

| DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit (Qiagen) | For high-yield DNA extraction from complex and challenging matrices like soil [3]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | A sterile, neutral solution used to moisten swabs for effective microbial collection without damaging cells [3]. |

| Illumina MiSeq System | A sequencing platform suitable for mid-output amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA, ITS) for microbiome characterization [3]. |

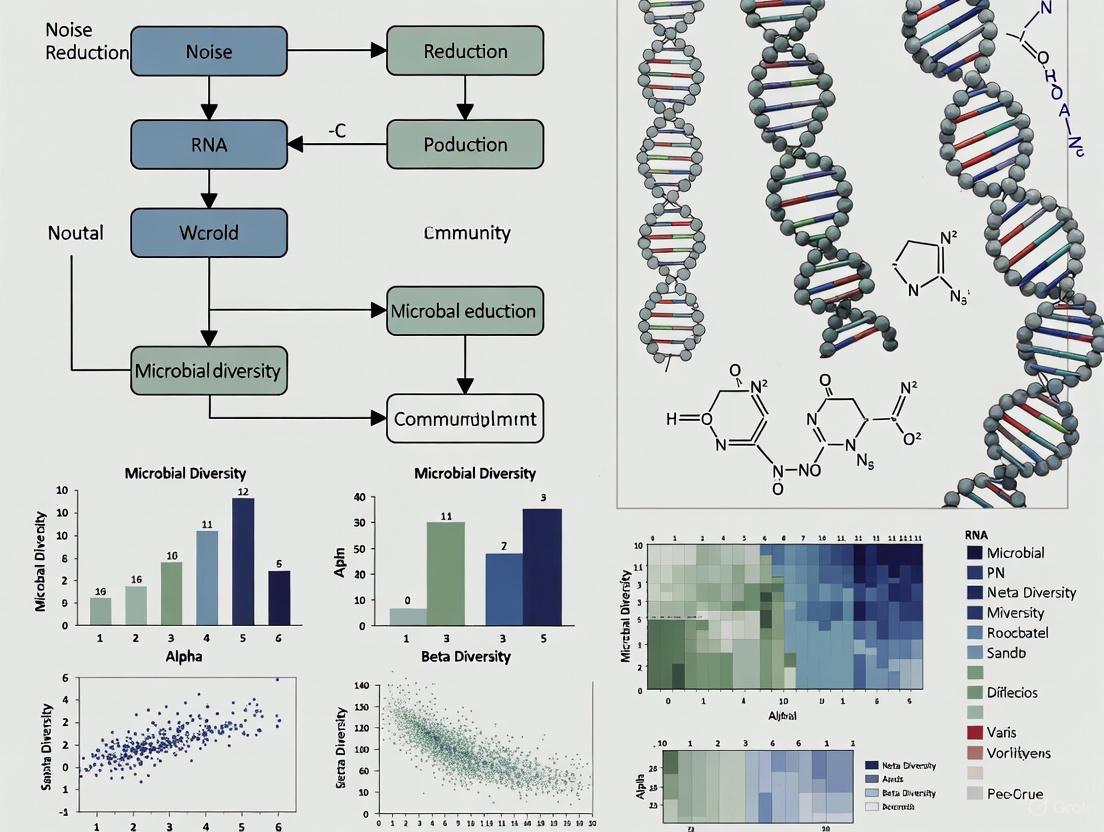

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Microbiome Contamination Analysis Workflow

Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are low-biomass samples particularly vulnerable to contamination? In low-biomass samples (e.g., tissues like placenta, tumors, or blood), the amount of target microbial DNA is very small. Contaminating DNA from reagents, kits, or the laboratory environment can constitute a large proportion of the total DNA recovered, effectively swamping the true biological signal [6] [7]. This can lead to incorrect conclusions, as evidenced by controversies in placental and tumor microbiome research [8].

Q2: How can I tell if my dataset is affected by batch effects? Batch effects occur when technical differences (e.g., different reagent lots, personnel, or sequencing runs) systematically alter your data. A key indicator is when your samples cluster more strongly by processing batch than by the biological groups of interest in ordination plots [8] [9]. This is especially problematic if the batch structure is confounded with your experimental conditions [8].

Q3: What is the difference between contamination and host DNA misclassification? Contamination is the introduction of external DNA from non-sample sources like reagents or the lab environment [8] [6]. Host DNA misclassification occurs when host DNA sequences (e.g., from human tissue) are incorrectly identified as microbial during bioinformatic analysis, which is a significant risk in samples where host DNA makes up the vast majority of sequenced material [8].

Q4: What are the most critical controls for a low-biomass microbiome study? It is strongly advised to include multiple types of process controls to account for various contamination sources [8] [6]. These should be processed alongside your actual samples through the entire workflow. Essential controls are listed in the table below.

Q5: Can I rely solely on bioinformatic decontamination tools? No. While bioinformatic decontamination is a valuable step, it cannot fully replace careful experimental design [8] [6]. These tools may struggle to distinguish signal from noise in extensively contaminated datasets, and well-to-well leakage can violate their core assumptions [8] [6]. The most robust strategy combines rigorous contamination prevention during sample collection and processing with subsequent bioinformatic cleaning.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Mitigating Contamination

Contamination is a critical challenge that requires vigilance at every stage of your workflow.

Prevention at the Source:

- Sample Collection: Use single-use, DNA-free collection materials. Decontaminate reusable equipment with solutions like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) to degrade DNA, not just ethanol which kills cells but may leave DNA intact [6].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, and clean suits to minimize contamination from skin, hair, or aerosols [6].

- Reagents: Use high-purity, molecular biology-grade reagents. Be aware that commercial DNA extraction kits and PCR reagents are known sources of contaminating DNA [7].

Detection and Diagnosis:

- Process Controls: Sequence your negative controls (e.g., blank extractions, no-template PCRs). The microbial profile of these controls represents your background contamination [8] [7].

- Compare to Contaminant Databases: Compare the taxa in your samples against known contaminant genera commonly found in reagents. The table below lists frequently observed contaminants [7].

Solutions:

Guide 2: Managing Batch Effects and Processing Bias

Batch effects can introduce artificial patterns that obscure or mimic true biological signals.

Prevention at the Source:

- Study Design: The single most important step is to avoid batch confounding. Ensure that your biological groups of interest (e.g., case vs. control) are evenly distributed across all processing batches (DNA extraction plates, sequencing runs, etc.) [8]. Use randomization or tools like BalanceIT for optimal sample placement [8].

- Standardization: Use identical protocols, reagents, and personnel for processing all samples whenever possible.

Detection and Diagnosis:

- Exploratory Data Analysis: Visualize your data using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA). If samples cluster strongly by batch rather than biology, you have a batch effect.

- Statistical Tests: Use PERMANOVA to test if the variance explained by the batch variable is significant.

Solutions:

Guide 3: Addressing Host DNA Misclassification

In host-derived samples, over 99.99% of sequenced reads can be host DNA, creating a risk of misclassification [8].

Prevention at the Source:

- Host Depletion: Wet-lab methods to enrich for microbial DNA include saponin-based lysis to remove host cells or kit-based probes to capture and remove host DNA (e.g., NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit) [8].

Detection and Diagnosis:

- Read Mapping: Check the percentage of reads that map to the host genome (e.g., human GRCh38) using aligners like Bowtie2 or BWA. A very high percentage (>99%) is typical for low-biomass samples and signals a high risk of misclassification [8].

Solutions:

- Bioinformatic Filtering: Rigorously filter out all reads that align to the host genome before performing taxonomic profiling.

- Improved Classification: Use sensitive and specific classification tools (e.g., Kraken2 with carefully curated databases) that are less likely to misassign host reads to microbial taxa [8].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Contaminant Genera Found in Reagents and Kits

This list, while not exhaustive, includes bacterial genera frequently identified as contaminants in laboratory reagents and DNA extraction kits [7].

| Contaminant Genus | Typical Source/Environment |

|---|---|

| Acinetobacter | Water, soil |

| Bacillus | Soil, water |

| Bradyrhizobium | Soil |

| Burkholderia | Soil, water |

| Corynebacterium | Human skin |

| Methylobacterium | Water, soil |

| Propionibacterium | Human skin |

| Pseudomonas | Water, soil |

| Ralstonia | Water |

| Sphingomonas | Water, soil |

| Stenotrophomonas | Water |

Table 2: Essential Process Controls for Low-Biomass Studies

A combination of control types is recommended to capture contamination from different sources [8] [6].

| Control Type | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Blank Extraction | No sample added to the extraction kit | Identifies contaminants from DNA extraction kits and reagents [7]. |

| No-Template PCR (NTC) | Ultrapure water added to the PCR mix | Identifies contaminants present in PCR master mixes [8]. |

| Sample Collection Control | Swab exposed to air or an empty collection tube | Identifies contaminants from the collection equipment and environment [6]. |

| Mock Community | A defined mix of microbial cells/DNA with known ratios | Evaluates bias and accuracy throughout the entire workflow [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Contamination-Aware DNA Extraction Workflow

This protocol outlines a rigorous approach for extracting DNA from low-biomass samples.

Key Materials:

- DNA-free collection kits (e.g., sterile swabs, tubes)

- DNA extraction kit (be aware of its inherent contaminant profile)

- PPE (gloves, lab coat, mask)

- DNA-free water

- Reagents for surface decontamination (e.g., 10% bleach, UV light)

Methodology:

- Pre-extraction Setup:

- Clean all work surfaces and equipment with a DNA-degrading solution (e.g., 10% bleach) followed by 80% ethanol to remove residual bleach [6].

- Use a dedicated pre-PCR workspace, ideally with a UV-equipped laminar flow hood.

- Include at least one blank extraction control and one mock community control for every batch of extractions.

Sample Handling:

- Process low-biomass samples before high-biomass samples to prevent cross-contamination.

- Change gloves frequently between handling different samples and controls.

DNA Extraction:

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for your chosen DNA extraction kit.

- Include all controls in the same extraction run as your samples.

Post-extraction:

- Quantify DNA using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit). Expect very low yields for low-biomass samples and controls.

- Store DNA at -20°C until ready for library preparation.

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Diagnosing and Correcting Batch Effects

This protocol uses bioinformatic tools to detect and mitigate batch effects in sequenced data.

Key Materials:

- Raw count table (e.g., ASV/OTU table) from your microbiome analysis pipeline.

- Sample metadata file that includes batch information (e.g., extraction date, sequencing run).

Methodology:

- Exploratory Visualization:

- Using R or Python, generate a PCoA plot (e.g., based on Bray-Curtis distance). Color the points by biological group and shape by batch.

- Visually inspect whether samples from the same batch cluster together.

Statistical Testing:

- Perform a PERMANOVA test (e.g., using the

adonis2function in R'sveganpackage) with the model:distance_matrix ~ biological_group + batch. - Assess the statistical significance and effect size of the

batchterm.

- Perform a PERMANOVA test (e.g., using the

Batch Effect Correction (if needed):

- Choose a correction method. For supervised correction with known batches,

ComBatorlimmaare common choices [9]. - Apply the correction to the transformed count data (e.g., CLR-transformed data).

- Important: Always correct for batch effects within the same study. Do not use this to combine different studies with fundamentally different protocols.

- Choose a correction method. For supervised correction with known batches,

Post-correction Validation:

- Repeat the PCoA plot and PERMANOVA test on the corrected data.

- Confirm that the batch effect is reduced while the biological signal is preserved.

Visualizations

This diagram outlines the major noise sources at each step of a low-biomass microbiome study and key strategies to mitigate them.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| DNA Degrading Solution (e.g., bleach) | Critical for surface decontamination; destroys contaminating DNA that ethanol alone leaves behind [6]. |

| Ultra-clean DNA Extraction Kits | Specifically designed for low-biomass or forensic applications; may have lower inherent contaminant levels. |

| Mock Microbial Communities | Defined mixes of microorganisms with known abundances; used as a positive control to evaluate technical bias and accuracy across the entire workflow [10]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Gloves, masks, and clean suits minimize the introduction of contaminating DNA from researchers [6]. |

| DNA-free Tubes and Water | Certified nucleic-acid-free consumables reduce the introduction of contaminating DNA from labware and reagents [6]. |

| Host Depletion Kits | Use probes or enzymatic treatments to selectively remove host DNA, thereby enriching the relative proportion of microbial DNA for sequencing [8]. |

| Cyclooctane-1,5-diamine | Cyclooctane-1,5-diamine |

| Heptane, 2,2,5-trimethyl- | Heptane, 2,2,5-trimethyl-, CAS:20291-95-6, MF:C10H22, MW:142.28 g/mol |

Why is contamination such a major concern in low-biomass microbiome studies?

In low-biomass microbiome studies, samples contain only minimal amounts of microbial DNA. This scarcity makes them particularly vulnerable to contamination from external DNA, which can constitute a large proportion of the final sequencing data and obscure true biological signals [6] [8].

The primary sources of this contamination include:

- Environmental contamination: DNA from reagents, kits, sampling equipment, and laboratory surfaces [6] [11]

- Human-derived contamination: Microbial DNA from researchers' skin, hair, or clothing introduced during sample handling [6]

- Cross-contamination (well-to-well leakage): Transfer of DNA between samples processed concurrently, such as in adjacent wells of a 96-well plate [6] [8]

- Host DNA misclassification: In host-associated samples, the majority of DNA may originate from the host, and this host DNA can sometimes be misidentified as microbial [8]

The central problem is proportionality: with minimal target DNA, even tiny amounts of contaminant DNA become significant, potentially leading to false conclusions about the microbial community present [6].

What are the key experimental controls needed for reliable low-biomass research?

Implementing comprehensive process controls is essential for identifying contamination sources. The table below summarizes the critical controls recommended for low-biomass studies:

Table: Essential Experimental Controls for Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies

| Control Type | Description | Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Extraction Controls | Reagents without sample taken through DNA extraction process | Identifies contamination from extraction kits and reagents | Blank extraction controls, library preparation controls [8] |

| Sampling Controls | Sterile collection devices exposed to sampling environment | Captures contamination from collection equipment and air | Empty collection kits, swabs exposed to air, surface swabs [6] |

| Process-Specific Controls | Controls representing specific contamination sources | Identifies contributions from individual processing steps | Sampling fluids, drilling fluids, preservation solutions [6] [8] |

| Full-Process Controls | Controls passing through entire experimental workflow | Represents all contaminants concurrently | No-template controls, blank controls included in each batch [8] |

Researchers should include multiple controls for each contamination source, as two controls are always preferable to one, with more recommended when high contamination is expected [6] [8]. These controls should be processed alongside actual samples through all experimental stages.

How can I prevent contamination during sample collection?

Proper sampling techniques are crucial for minimizing initial contamination. Follow these evidence-based protocols:

Decontaminate equipment and surfaces: Treat tools, vessels, and gloves with 80% ethanol (to kill microorganisms) followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (to remove residual DNA). Use sodium hypochlorite (bleach), UV-C exposure, or commercial DNA removal solutions where practical [6].

Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, cleansuits, and shoe covers to limit sample contact with human-derived contaminants. Change gloves frequently and ensure they don't touch anything before sample collection [6].

Employ sterile, single-use materials: Use pre-sterilized, DNA-free collection vessels and swabs whenever possible. Keep containers sealed until the moment of sample collection [6].

Implement rigorous training: Ensure all personnel involved in sampling receive comprehensive instruction on contamination avoidance protocols [6].

What computational methods can decontaminate low-biomass microbiome data?

Several computational approaches have been developed to identify and remove contaminant signals from low-biomass microbiome data. The table below compares key methods and their applications:

Table: Computational Decontamination Tools for Low-Biomass Microbiome Data

| Tool/Method | Approach Category | Key Features | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| micRoclean R package [11] | Control-based with two pipelines | Offers "Original Composition Estimation" and "Biomarker Identification" pipelines; Provides filtering loss statistic to prevent over-filtering | 16S rRNA data; Handles multiple batches and well-to-well leakage |

| decontam [11] | Control and prevalence-based | Identifies contaminant features based on prevalence in negative controls or prevalence in low-concentration samples | 16S rRNA and shotgun data; Requires negative controls or sample quantitative data |

| SCRuB [11] | Control-based | Accounts for well-to-well leakage contamination; Can partially remove reads rather than entire features | 16S rRNA data; Especially useful when spatial well information is available |

| MicrobIEM [11] | Control-based | Leverages negative control samples to identify and remove contaminants | 16S rRNA data; User-friendly interface |

| Blocklist Methods [11] | Predefined contaminant lists | Removes features previously identified in literature as common contaminants | Screening step before more sophisticated methods |

The micRoclean package is particularly valuable as it provides guidance on pipeline selection based on research goals and implements a filtering loss statistic to quantify the impact of decontamination on the overall data structure, helping prevent over-filtering [11].

How should I design my study to avoid batch confounding?

Batch effects occur when technical variations between processing batches correlate with biological variables of interest, creating artifactual signals. Avoid this through careful experimental design:

Strategic sample randomization: Actively balance phenotypes and covariates of interest across batches rather than relying on random assignment. Use tools like BalanceIT to generate unconfounded batches [8].

Process cases and controls together: Ensure each batch includes similar ratios of case and control samples to prevent batch effects from being misinterpreted as biological signals [8].

Include controls in every batch: Place negative controls in each processing batch to account for batch-specific contamination profiles [8].

Document all processing variables: Record details including reagent lots, equipment used, personnel, and processing dates to facilitate batch effect detection during analysis [8].

What specialized reagents and equipment are essential for low-biomass work?

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies

| Item | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-free Collection Swabs/Containers | Sample collection without introducing contaminants | Pre-sterilized, single-use; Verify DNA-free status [6] |

| Nucleic Acid Degrading Solutions | Eliminate contaminating DNA from surfaces and equipment | Sodium hypochlorite, specialized DNA removal solutions [6] |

| Sample Preservation Solutions | Stabilize microbial DNA without degradation | Commercial stabilizers allow transport without freezing [12] |

| DNA Extraction Kits with Low-Biomass Protocols | Optimized nucleic acid recovery from minimal starting material | Validate performance with target sample types [12] |

| Ultra-Pure, DNA-Free Reagents | Minimize introduction of contaminant DNA | Verify DNA-free status of all reagents, including water [6] |

| Multiple Negative Control Types | Identify various contamination sources | Include extraction, sampling, and process controls [8] |

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between major contamination sources in low-biomass studies and the corresponding control strategies:

Where can I find validated analysis pipelines for low-biomass data?

Several web-based platforms offer specialized analysis pipelines:

MicrobiomeAnalyst: A comprehensive web-based tool that provides statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. While it doesn't process raw sequencing data, it accepts feature abundance tables and offers 19 different statistical analysis and visualization methods specifically suited for microbiome data [13].

micRoclean R package: An open-source R package specifically designed for decontaminating low-biomass 16S rRNA data. It includes two specialized pipelines - one for estimating original composition and another for biomarker identification - and provides a filtering loss statistic to prevent over-filtering [11].

When using these platforms, ensure you:

- Upload properly processed feature abundance tables and metadata

- Specify appropriate normalization methods for low-biomass data

- Apply decontamination algorithms using your negative controls

- Use the provided R command history to maintain reproducibility [13]

High-throughput sequencing technologies, such as 16S rRNA gene amplicon and shotgun metagenomic sequencing, have revolutionized microbial community research. However, the data generated from these methods possess several intrinsic characteristics that complicate statistical analysis and biological interpretation. The three most critical challenges are compositionality, sparsity, and zero-inflation. Compositionality arises because sequencing data provides relative, not absolute, abundances, constrained to a constant sum (e.g., 1 or 100%) [14] [15]. Sparsity refers to the phenomenon where a large proportion of microbial taxa are detected in only a small fraction of samples [16]. Zero-inflation describes the excess of zero counts in the data, which can stem from both true biological absence (biological zeros) and technical limitations like low sequencing depth or sampling effort (technical zeros) [16] [17]. Understanding and mitigating the effects of these properties is essential for any robust microbiome data analysis pipeline.

? Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the practical difference between sparsity and zero-inflation in microbiome data? While these terms are related, they describe different aspects of the data. Sparsity broadly refers to the fact that the data matrix contains mostly zero values, meaning most taxa are absent from most samples [16]. Zero-inflation is a specific statistical property indicating that the number of observed zeros is significantly greater than what would be expected under a standard count distribution (e.g., Poisson or Negative Binomial) [14] [16]. All zero-inflated datasets are sparse, but not all sparse datasets are necessarily zero-inflated from a modeling perspective.

2. Why is compositionality a problem for measuring associations between microbes? Because the abundance of each taxon is not independent, compositionality can induce spurious correlations [18] [15]. If one taxon's abundance increases, the relative abundances of all others must decrease to maintain the constant sum. This negative bias can make it appear that taxa are negatively correlated even when no biological interaction exists, severely complicating network inference and differential abundance testing [15].

3. How can I determine if a zero count is biological or technical in origin? Without prior biological knowledge or experimental controls (e.g., spike-ins), definitively distinguishing between the two is difficult [16] [6]. However, several strategies can help infer the nature of zeros:

- Prevalence and Context: Zeros that occur consistently across all samples in a group (group-wise structured zeros) are more likely to be biological [16].

- Controls and Denoising: The use of negative controls during sampling and sequencing can help identify technical contaminants [6]. Computational denoising methods like

mbDenoisecan also help recover true abundance levels by borrowing information across samples and taxa [17].

4. My dataset has many rare taxa. Should I filter them before analysis? Filtering rare taxa is a common preprocessing step to reduce noise and the burden of multiple testing [16] [18]. A prevalent filter (e.g., removing taxa present in less than 5-10% of samples) is often recommended. However, this step must be performed carefully, as it can remove valuable biological signal and alter the compositional structure if the discarded reads are not accounted for [18]. The choice of threshold is often a balance between reducing noise and retaining information.

5. Which is more critical to address first: compositionality or zero-inflation?

The order of operations depends on your analytical goal. For diversity metrics and ordination, addressing compositionality via appropriate transformations (e.g., Centered Log-Ratio - CLR) is often the first step [9]. For differential abundance testing or network inference, an integrated approach that simultaneously handles both properties is ideal. Methods like COZINE (for networks) and DESeq2-ZINBWaVE (for differential abundance) are specifically designed for this purpose [16] [15].

? Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High False Positives in Differential Abundance Analysis

- Symptoms: Identifying a large number of differentially abundant taxa that lack biological plausibility or cannot be validated.

- Potential Causes:

- Unaccounted for Confounders: Technical batch effects or environmental variables that are correlated with the phenotype of interest [9].

- Failure to Model Zero-Inflation: Using standard count models that do not account for excess zeros, leading to biased estimates [16].

- Improper Normalization: Using raw counts or simple rarefaction without considering compositionality and its effect on variance [16].

- Solutions:

- Step 1: Apply supervised (e.g.,

ComBat,limma) or unsupervised (e.g., PCA correction) methods to remove unwanted variation from known and unknown technical sources [9]. - Step 2: Use differential abundance methods explicitly designed for zero-inflated and compositional data. A combined approach using

DESeq2-ZINBWaVEfor zero-inflated taxa and standardDESeq2for taxa with group-wise structured zeros has been shown to be effective [16]. - Step 3: Ensure proper normalization using methods that are compositionally aware, such as those employing geometric means (e.g.,

DESeq2's median-of-ratios) or specialized tools likeWrench[16].

- Step 1: Apply supervised (e.g.,

Problem: Unstable or Uninterpretable Microbial Networks

- Symptoms: Inferred co-occurrence networks are overly dense, dominated by negative associations, or change drastically with minor changes in the data.

- Potential Causes:

- Spurious Correlations from Compositionality: Using Pearson or Spearman correlation on relative abundance data without correction [15] [19].

- Impact of Rare Taxa: Including taxa with very low prevalence creates associations based almost entirely on matching zeros, which are statistically unreliable [18].

- Environmental Confounding: Unmeasured environmental variables drive co-occurrence patterns, which are misinterpreted as direct biotic interactions [18].

- Solutions:

- Step 1: Preprocess data carefully. Apply a prevalence filter and use a method like

COZINEorSPIEC-EASIthat directly models compositionality and zero-inflation for network inference [18] [15]. - Step 2: For longitudinal data, use tools like

LUPINEthat leverage information from multiple time points to infer more stable, dynamic networks [19]. - Step 3: Incorporate measured environmental factors as additional nodes in the network or regress out their effect before inference to disentangle biotic from abiotic associations [18].

- Step 1: Preprocess data carefully. Apply a prevalence filter and use a method like

Problem: Poor Performance in Phenotype Prediction Models

- Symptoms: Machine learning models trained on microbiome data have low predictive accuracy on validation sets or fail to generalize to other datasets.

- Potential Causes:

- Solutions:

- Step 1: Denoise the data. Use a method like

mbDenoise, which employs a Zero-Inflated Probabilistic PCA (ZIPPCA) model to learn the latent biological structure and recover true abundances, thereby improving downstream prediction tasks [17]. - Step 2: Apply feature selection. Before model training, perform robust differential abundance analysis or use regularization techniques (e.g., lasso) to select a smaller set of informative taxa.

- Step 3: Correct for batch effects. When pooling data from multiple studies for greater predictive power, use batch correction methods to harmonize the datasets [9].

- Step 1: Denoise the data. Use a method like

? Comparative Tables of Methods and Workflows

Table 1: Overview of Statistical Software for Addressing Data Challenges

| Tool Name | Primary Purpose | Key Features | Addresses | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SparseDOSSA 2 | Simulation & Benchmarking | Generates realistic synthetic microbiome profiles with known structure | Compositionality, Zero-Inflation, Sparsity | [14] |

| COZINE | Network Inference | Uses a multivariate Hurdle model for conditional dependencies without pseudo-counts | Compositionality, Zero-Inflation | [15] |

| DESeq2-ZINBWaVE | Differential Abundance | Applies observation weights to handle zero-inflation within a robust count framework | Zero-Inflation, Sparsity | [16] |

| mbDenoise | Data Denoising | Uses a ZIPPCA model to recover true abundance and distinguish technical/biological zeros | Zero-Inflation, Technical Noise | [17] |

| LUPINE | Longitudinal Network Inference | Leverages past time point information to infer dynamic microbial interactions | Compositionality, Longitudinal Sparsity | [19] |

| PCA Correction | Confounding Adjustment | Unsupervised method to remove variation captured by top principal components | Technical Variation, Batch Effects | [9] |

Table 2: Guide to Selecting a Differential Abundance Workflow Based on Data Characteristics

| Data Characteristic | Recommended Workflow | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High zero-inflation, but no group-wise structured zeros | Use DESeq2-ZINBWaVE |

The ZINBWaVE weights effectively control the false discovery rate induced by scattered zero counts [16]. |

| Presence of group-wise structured zeros | Use standard DESeq2 |

Its penalized likelihood estimation provides finite parameter estimates and appropriate p-values for taxa that are absent in an entire group [16]. |

| Mixed zero patterns (both scattered and structured) | Combined Approach: Run both DESeq2-ZINBWaVE and DESeq2, then merge results. |

This hybrid strategy robustly handles all types of zeros commonly found in microbiome data [16]. |

? Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Robust Differential Abundance Analysis with DESeq2-ZINBWaVE and DESeq2

This protocol outlines a combined analysis pipeline to handle zero-inflation and group-wise structured zeros [16].

- Data Preprocessing: Begin with a raw count table. Apply a prevalence filter (e.g., retain taxa present in at least 5% of samples). Do not rarefy.

- Run DESeq2-ZINBWaVE Analysis:

- Compute observation weights using the

ZINBWaVEpackage to model the zero inflation. - Input the count table and weights into

DESeq2for differential abundance testing. This step is optimal for taxa with scattered zeros.

- Compute observation weights using the

- Run Standard DESeq2 Analysis:

- Run

DESeq2on the same filtered count table without using weights. This step is optimal for taxa with group-wise structured zeros.

- Run

- Results Integration:

- Combine the list of significant taxa from both analyses, taking care to resolve overlaps.

- The final output is a comprehensive list of differentially abundant taxa, robust to the various patterns of zeros.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the combined analysis pipeline:

Protocol 2: Microbial Network Inference with COZINE

This protocol details steps for inferring a microbial association network that accounts for compositionality and zero-inflation without using pseudo-counts [15].

- Input: Use the raw OTU or ASV count table as input.

- Transformation: Transform the data into two representations:

- A binary matrix indicating presence (1) or absence (0).

- A continuous matrix where non-zero values are transformed using the Centered Log-Ratio (CLR), and zero values are preserved as zeros.

- Model Fitting: Fit the multivariate Hurdle model to the combined data representations. This model jointly captures:

- Dependencies between presences/absences of taxa.

- Dependencies between continuous abundances.

- Dependencies between the binary and continuous parts.

- Network Estimation: Use neighborhood selection with a group-lasso penalty to estimate a sparse set of conditional dependencies (edges) between taxa.

- Output: The result is an undirected network graph where edges represent robust, direct ecological relationships (co-occurrence or mutual exclusion).

The conceptual framework of the COZINE method is shown below:

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Reference / Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| SparseDOSSA 2 | Software/Bioconductor Package | Statistical model to simulate realistic synthetic microbiome data for methods benchmarking. | [14] |

| ZINBWaVE Weights | Algorithm / R Package | Generates observation weights for zero-inflated count data, enabling use with tools like DESeq2 and edgeR. |

[16] |

| Negative Controls | Experimental Reagent | DNA-free water or swabs used during sampling and DNA extraction to identify contaminating sequences. | [6] |

| CLR Transformation | Mathematical Transform | Transforms compositional data to a Euclidean space to help break the sum constraint before analysis. | [9] [15] |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Laboratory Supply | Clean suits, masks, and gloves to minimize the introduction of contaminant DNA from researchers during sampling of low-biomass environments. | [6] |

| DNA Decontamination Solutions | Laboratory Reagent | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), UV-C light, or commercial DNA removal solutions to sterilize surfaces and equipment. | [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of noise in microbial community data? Noise in microbiome data primarily stems from technical variation introduced during sample processing and data generation. This includes batch effects from different sequencing runs, variations in DNA extraction protocols, sample storage conditions, primer choices, and sequencing depths [9]. Furthermore, the inherent compositionality of the data—where abundances represent relative proportions rather than absolute counts—is a major source of spurious correlations if not handled properly [20] [21].

FAQ 2: How does noise specifically affect alpha and beta diversity metrics? Noise can significantly bias both alpha and beta diversity metrics. Technical variations in sequencing depth can artificially inflate or deflate richness estimates (a key alpha diversity component) because a more deeply sequenced sample is more likely to exhibit greater diversity by chance [22]. For beta diversity, which measures differences in community composition between samples, technical covariates (e.g., different study protocols) can introduce variation that obscures true biological signals. If these technical factors are confounded with the phenotype of interest, they can lead to false conclusions about group differences [9].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between supervised and unsupervised noise correction methods, and when should I use each?

- Supervised methods (e.g., ComBat, limma, Batch Mean Centering) require you to specify the known sources of unwanted variation (e.g., batch ID) in advance. They are effective when all major technical confounders are known and measured [9].

- Unsupervised methods (e.g., PCA correction, ReFactor, SVA) infer the sources of unwanted variation directly from the data itself. These are advantageous when technical variables are unmeasured or unknown, a common scenario in meta-analyses [9].

The choice depends on your data: use supervised correction when technical batches are well-documented, and unsupervised approaches when dealing with complex or poorly annotated datasets where hidden confounders are suspected [9].

FAQ 4: Why are microbiome association tests particularly vulnerable to noise? Microbiome association tests are vulnerable because the data is compositional, sparse (zero-inflated), and over-dispersed [9] [20]. Compositionality means that an increase in one taxon's relative abundance necessarily causes a decrease in others, creating spurious negative correlations [21]. Noise from technical sources can amplify these inherent properties, leading to both false positive and false negative findings when identifying microbial signatures of disease [9] [20].

FAQ 5: How can I determine if my diversity metrics have been affected by uneven sequencing depth? Generating alpha rarefaction curves is a standard diagnostic approach. This curve plots the number of sequences sampled (rarefaction depth) against the expected diversity value. If the curve has not reached a stable plateau for your samples, it indicates that the observed diversity is still sensitive to sequencing effort, and the metrics are unreliable. A common practice is to rarefy (subsample) all samples to a depth where the curves begin to stabilize, thus comparing diversity at a standardized sequencing depth [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Microbial Signatures Across Studies

Symptoms: A microbial taxon identified as a significant biomarker in one study fails to replicate in another study of the same disease.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected Batch Effects | Perform PERMANOVA on beta diversity using "Study" or "Batch" as a factor. A significant result indicates strong batch effects. | Apply a supervised batch correction method like ComBat [9] or use a meta-analysis framework like Melody that does not require data pooling [20]. |

| Compositional Data Artifacts | Check if the association results change dramatically when using a different reference feature in a log-ratio method. | Use compositionally-aware models like those in ANCOM-BC2, LinDA, or the Melody framework, which are designed to handle relative abundance data [20]. |

| Inadequate Handling of Sparsity | Examine the prevalence (number of non-zero samples) of your identified signatures. Very rare taxa are less reproducible. | Use methods robust to sparsity or apply careful prevalence filtering before analysis. Frameworks like Melody avoid zero imputation to prevent bias [20]. |

Problem 2: Diversity Metrics are Confounded by Technical Variables

Symptoms: A principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plot of beta diversity shows clear separation by technical groups (e.g., sequencing run, extraction kit) instead of, or in addition to, biological groups.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Major Technical Variance | Check the variance explained by top principal components (PCs). If early PCs are strongly correlated with technical variables, they are confounding the analysis. | Apply an unsupervised correction method like PCA correction, which regresses out the effect of the first few PCs before downstream analysis [9]. |

| Uneven Sequencing Depth | Compare the library sizes (total reads per sample) between groups. A difference greater than ~10x is a concern [22]. | For diversity analyses, use rarefaction to a common depth [22]. For differential abundance, use methods with built-in normalization like DESeq2 (VST) or EdgeR (logCPM) [9]. |

Quantitative Data on Noise Correction Performance

The following table summarizes findings from a comparative analysis of different noise correction methods, highlighting their performance in key analytical tasks [9].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Noise Correction Methods in Microbiome Analysis

| Method | Type | Key Requirement | Performance in Biomarker Discovery (False Positive Reduction) | Performance in Phenotype Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Supervised | Known batch variables | Effective | Improves prediction when technical variables are known |

| limma | Supervised | Known batch variables | Effective | Improves prediction when technical variables are known |

| Batch Mean Centering (BMC) | Supervised | Known batch variables | Effective | Improves prediction when technical variables are known |

| PCA Correction | Unsupervised | None | Comparable to supervised methods | Improves prediction only when technical variables contribute to most of the variance |

| VST (DESeq2) | Transformation | - | Often used as a pre-processing step before correction | - |

| logCPM (EdgeR) | Transformation | - | Often used as a pre-processing step before correction | - |

| CLR | Transformation | - | Makes data more suitable for factor analysis like PCA | - |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Evaluation and Correction

Protocol A: Evaluating Technical Noise via Principal Components Analysis

This protocol helps diagnose the presence and sources of unwanted technical variation in your dataset.

- Data Transformation: Transform your microbial abundance count data using a variance-stabilizing method. The Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation is recommended as it handles compositionality and makes data more suitable for PCA [9].

- Perform PCA: Conduct Principal Components Analysis on the transformed data.

- Correlate PCs with Metadata: Statistically test (e.g., using PERMANOVA or linear models) the association between the top principal components and all available technical and biological metadata (e.g., sequencing batch, DNA concentration, study center, phenotype of interest).

- Interpretation: If the top PCs are significantly associated with technical variables, this indicates substantial technical noise that requires correction before association testing [9].

Protocol B: Applying Supervised Batch Correction with ComBat

This protocol uses the ComBat method to remove batch effects when batch identities are known.

- Input Data: Use a transformed feature table (e.g., CLR-transformed or VST-transformed counts). The data should be in a matrix where rows are features (taxa/ASVs) and columns are samples.

- Specify Batches and Model: Define the known batch variable(s) for each sample. Optionally, specify a model matrix for the biological variable of interest (e.g., disease status) to protect this signal during correction.

- Run ComBat: Apply the ComBat algorithm (available in R packages like

sva) using the parametric empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects [9]. - Downstream Analysis: Use the batch-corrected data for subsequent diversity or association analyses.

Protocol C: Meta-analysis with the Melody Framework

This protocol outlines how to use the Melody framework for a robust meta-analysis of multiple microbiome studies without pooling raw data, thereby avoiding batch effect issues.

- Generate Study-Specific Summaries: For each study individually, fit a quasi-multinomial regression model linking the microbiome count data to the covariate of interest. This generates summary statistics (association estimates and variances) for each microbial feature [20].

- Harmonize Statistics: The Melody framework internally harmonizes these study-specific summary statistics. It does not require rarefaction, zero imputation, or batch effect correction of the raw data [20].

- Estimate Sparse Meta-Association: Melody frames the meta-analysis as a best subset selection problem. It uses a cardinality constraint to identify the sparsest set of microbial features (driver signatures) whose consistent absolute abundance changes can explain the observed relative abundance associations across all studies [20].

- Identify Signatures: The output is a set of robust, generalizable microbial signatures with non-zero meta-association coefficients.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting appropriate noise reduction strategies in microbiome analysis, based on data characteristics and known information about technical batches [9] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Noise Reduction in Microbiome Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| CLR Transformation | Data transformation that handles compositionality by using log-ratios relative to the geometric mean of a sample. | Makes data more suitable for PCA and other Euclidean-based methods [9]. |

| DESeq2 (VST) | Variance-Stabilizing Transformation for count data. | Normalizes for sequencing depth and variance heterogeneity, often used prior to batch correction [9]. |

| EdgeR (logCPM) | Log-counts-per-million transformation. | Another common normalization and transformation method for count data [9]. |

| ComBat | Supervised batch effect correction using empirical Bayes. | Effective when all major batch variables are known and documented [9]. |

| PCA Correction | Unsupervised method that regresses out top principal components. | Useful for removing unknown sources of technical variation; effective for reducing false positives [9]. |

| Melody | Summary-data meta-analysis framework. | Identifies generalizable microbial signatures from multiple studies without needing to pool raw data, avoiding batch effects [20]. |

| R package 'mina' | Integrates compositional and co-occurrence network analysis. | Identifies representative taxa and compares microbial networks across conditions to find key interactions [23]. |

| SPIEC-EASI | Compositionally-aware network inference tool. | Infers microbial co-occurrence networks while mitigating spurious correlations caused by compositionality [21]. |

| 1-Decene, 1-ethoxy- | 1-Decene, 1-ethoxy-, CAS:61668-40-4, MF:C12H24O, MW:184.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Z)-Pent-2-enyl butyrate | (Z)-Pent-2-enyl Butyrate CAS 42125-13-3 |

The De-noising Toolkit: Experimental and Computational Strategies for Cleaner Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical sources of noise in microbial community data, and how can I control for them? Technical covariates, including sample storage, cell lysis protocol, DNA extraction method, preparation kit, and primer choice, systematically introduce unwanted variation and bias relative abundances [9]. Control these by standardizing protocols across your experiment, using spike-in controls to quantify technical noise [24], and applying statistical correction methods a priori to adjust for both known and unknown sources of variation [9].

2. How can I design an experiment to reliably distinguish true biological signals from technical noise? Implement a replicated sampling design. The DIVERS (Decomposition of Variance Using Replicate Sampling) protocol is a powerful approach [24]. For a time-series study, at each time point, collect two spatial replicate samples from randomly chosen locations. Split one of these spatial replicates in half to create two technical replicates. Use a spike-in strain during sample processing to later calculate absolute abundances. This design allows statistical decomposition of variance into temporal, spatial, and technical components [24].

3. My microbiome data is compositional. What is the best way to transform it before analysis to reduce artifacts? The choice of transformation can depend on the subsequent analysis. For general purpose dimensionality reduction or factor analysis like PCA, the Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation is widely recommended as it breaks the dependency between features inherent in compositional data [9]. Other transformations like Variance Stabilizing Transformation (VST) or logCPM are also used, but CLR is particularly suited for compositional data [9] [5].

4. Which alpha diversity metrics should I use to get a comprehensive view of my community? No single metric captures all aspects of diversity. It is recommended to use a suite of metrics that collectively characterize:

- Richness: The number of species or ASVs (e.g., Observed features).

- Dominance/Evenness: The distribution of abundances among species (e.g., Berger-Parker index, which has a clear biological interpretation as the proportion of the most abundant taxon).

- Phylogenetic Diversity: The evolutionary relatedness of community members (e.g., Faith's PD).

- Information: An integrated measure of richness and evenness (e.g., Shannon entropy) [5]. Using this set provides a more robust and comprehensive analysis.

5. How can I identify if my analysis is being confounded by unmeasured technical variables? Perform a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on your data and color the samples by known batch variables (e.g., extraction date, sequencing run). If the top principal components are strongly associated with these technical variables, confounding is likely [9]. An unsupervised PCA correction approach can then be applied to regress out these confounding effects, even for unmeasured variables [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Unreplicable Differential Abundance Results

Potential Causes:

- Confounding technical variables (e.g., different DNA extraction kits used in case vs. control groups) [9].

- Analysis performed on relative abundances, which are susceptible to compositionality effects [24].

- Inadequate statistical power or failure to account for multiple hypotheses testing.

Solutions:

- Statistically Correct for Noise: Apply a background noise correction method. For a supervised approach (when technical variables are known), use ComBat or limma. For an unsupervised approach (to also account for hidden factors), use PCA correction [9].

- Use Absolute Abundance: Whenever possible, move beyond relative abundances. Employ a spike-in control during DNA extraction to estimate and use absolute microbial abundances in your models, which avoids compositionality artifacts [24].

- Validate Findings: If pooling datasets, ensure that batch effects are corrected. Use a discovery dataset and a held-out validation dataset to confirm your results [9].

Problem: Inability to Determine if Abundance Changes are Temporal, Spatial, or Noise

Potential Cause: The experimental design does not allow for the separation of these different sources of variability.

Solution: Implement the DIVERS Workflow [24] The following experimental and computational workflow is designed to decompose variance into its core components.

Problem: Choosing the Wrong Alpha Diversity Metric Leads to Misinterpretation

Potential Cause: Selecting an alpha diversity metric without understanding what aspect of diversity (richness, evenness, phylogeny) it measures.

Solution: Use a Category-Based Suite of Metrics [5] The table below summarizes key metrics and their primary purpose to guide your selection.

| Category | Purpose | Recommended Metric | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Quantifies the number of distinct types (e.g., ASVs). | Observed Features | The total number of unique ASVs in a sample. Simple and intuitive. |

| Dominance | Measures the uniformity of abundance distribution. | Berger-Parker Index | The proportion of the most abundant taxon in the community. |

| Phylogenetic | Incorporates evolutionary relationships between members. | Faith's PD | The sum of the branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree for all taxa in a sample. |

| Information | Integrates richness and evenness into a single value. | Shannon Entropy | Increases with both the number of ASVs and the evenness of their distribution. |

| (Methanol)trimethoxyboron | (Methanol)trimethoxyboron|High-Purity Research Chemical | Bench Chemicals | |

| 1-Hexylallyl formate | 1-Hexylallyl formate, CAS:84681-89-0, MF:C10H18O2, MW:170.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Spike-in Control (e.g., Synthetic Community or Unique Strain) | Added in known quantities prior to DNA extraction to enable the estimation of absolute abundances from sequencing data, countering compositionality effects [24]. |

| Standardized DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil) | Ensures consistent and reproducible lysis of microbial cells and DNA recovery across all samples, minimizing a major source of technical variation [9]. |

| Sterile Swab Kits (e.g., FloqSwabs) | For standardized collection of microbiome samples from surfaces, as used in controlled analog studies [3]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | A neutral buffer used for moistening swabs and resuspending samples during processing without altering the microbial community [3]. |

| Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) & 16S rRNA Primers | For amplicon-based profiling of fungal (ITS) and bacterial (16S) communities, respectively. Primer choice is a known source of bias and must be consistent [25] [9]. |

| Standardized Sequencing Kit (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) | Provides a controlled protocol for library preparation and sequencing, reducing batch effects introduced during this final data generation step [3] [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is computational decontamination and why is it critical in microbial community analysis? Computational decontamination refers to the use of bioinformatics tools to identify and remove DNA sequences that do not originate from the target sample but are introduced through contamination. This is a crucial noise reduction step because contamination falsely inflates within-sample diversity, obscures true biological differences between samples, and can lead to erroneous conclusions, such as false positive pathogen identification or incorrect ancestral gene reconstructions [26] [27]. In low-biomass environments, contaminants can comprise a significant fraction of sequencing reads, severely compromising data integrity [27].

2. My metagenomic dataset is from a low-biomass environment. What is the best decontamination approach?

For low-biomass samples (where contaminant DNA concentration [C] is similar to or greater than sample DNA [S]), the prevalence-based method is highly recommended. This method, implemented in tools like decontam, identifies contaminants by comparing their prevalence (presence/absence) in true biological samples versus negative control samples processed alongside them. Contaminants will have a significantly higher prevalence in negative controls due to the absence of competing sample DNA [27]. The frequency-based method, which relies on an inverse correlation between contaminant frequency and total DNA concentration, becomes less reliable in these scenarios [27].

3. How can I distinguish a true Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) event from contamination in a genome assembly?

Distinguishing HGT from contamination requires analyzing the genomic context. Contamination often appears as entire contigs or scaffolds where the majority of encoded proteins have taxonomic labels discordant with the target organism. In contrast, HGT events are typically single genes or small genomic regions embedded within contigs that are otherwise consistent with the host genome. Tools like ContScout combine reference database classification with gene position data, allowing them to mark and remove entire alien contigs while largely retaining HGT signals [26].

4. I suspect my DNA sequencing library is contaminated with cloned cDNA. How can I detect and remove it?

Cloned cDNAs lack introns and can be identified by the presence of "clipped" reads at exon boundaries in genomic alignments. The tool cDNA-detector is specifically designed for this purpose. It uses a binomial model to test if the fraction of clipped reads at exon boundaries is significantly higher than the background, identifying candidate contaminant transcripts. It can then remove these contaminant reads from the alignment file (BAM), reducing the risk of spurious variant or peak calls [28].

5. What are the most common sources of contamination I should be aware of? Contamination can originate from multiple sources, broadly categorized as:

- External Contamination: From laboratory reagents, collection instruments, laboratory surfaces and air, or research personnel [27] [3].

- Internal/Cross-Contamination: Occurs when samples mix with each other during processing or sequencing [27].

- Human Contamination: A very common type, especially in human microbiome studies, requiring removal of human reads from microbial data [29].

- Specific Contaminants: Bacterial sequences are the most common contaminant in eukaryotic genomes, followed by fungi, plants, and metazoans. Common bacterial genera found as contaminants include Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Escherichia/Shigella [26] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Positive Contamination Calls in Low-Diversity Samples

Problem: Your decontamination tool is flagging an unexpectedly high number of native, low-abundance taxa as contaminants.

Solution:

- Adjust Thresholds: Manually review and increase the significance threshold (e.g., the P-value or score statistic) in your decontamination tool. This makes the classification more conservative.

- Leverage Negative Controls: If available, switch to or combine with a prevalence-based method using sequenced negative controls. This directly identifies sequences that are more abundant in controls than in true samples [27].

- Validate with Coverage: Investigate the coverage and distribution of the flagged sequences. True, rare biosphere members will often have even, if low, coverage across their contigs, while contaminants might have patchy or inconsistent coverage.

Issue 2: Poor Contaminant Identification in Genomes with Limited Reference Data

Problem: When processing a genome from a poorly studied organism, the decontamination tool fails to classify a large portion of sequences, allowing contaminants to go undetected.

Solution:

- Use Protein-Based Tools: Tools that use protein sequences (e.g.,

ContScout,Conterminator) for taxonomic classification are often more sensitive in this scenario because protein sequences evolve slower than DNA, allowing for better detection of evolutionary distant contaminants [26]. - Multi-Tool Consensus: Run multiple decontamination tools and look for sequences flagged by a consensus of them. Over 95% of proteins tagged by both

ConterminatorandBASTAwere also identified as alien byContScout, indicating high-confidence contaminants [26]. - Manual Curation: For critical projects, tools like

Anvi'ocan be used to visualize contig statistics (e.g., GC content, tetranucleotide frequency, differential coverage) to manually identify and remove contaminant contigs [27].

Issue 3: Decontamination Workflow is Too Slow for Large Metagenomic Datasets

Problem: The similarity search step in your decontamination pipeline is a computational bottleneck.

Solution:

- Optimize Search Tools: Use speed-optimized tools like

DIAMOND(BLASTX-like searches) orMMseqs2for the alignment step.ContScoutsupports both and reports that the similarity search can account for 80-99% of the total run time, so this is the key step to optimize [26]. - Pre-Filter with Fast Classifiers: Use a fast k-mer-based classifier like

Krakenas an initial filter to quickly remove reads that are clearly human or from other known contaminant sources before a more sensitive alignment [30] [29]. - Leverage Containerization: Use the Docker container provided by tools like

ContScoutto ensure all dependencies are correctly configured and to facilitate deployment on high-performance computing clusters [26].

Comparison of Computational Decontamination Tools

The table below summarizes key tools for different decontamination scenarios.

| Tool Name | Primary Use Case | Input Data | Core Method | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ContScout [26] | Removal of contaminant proteins from annotated genomes | Protein sequences, Annotated Genomes | Taxonomy-aware protein similarity search + contig consensus | High specificity; can distinguish HGT from contamination [26] |

| Decontam [27] | Identifying contaminants in marker-gene & metagenomic data | ASV/OTU Table (from 16S rRNA) | Prevalence in negative controls or inverse frequency to DNA concentration | Simple statistical classification; integrates easily with QIIME2/R workflows [27] |

| cDNA-detector [28] | Detecting/removing cloned cDNA in NGS libraries | BAM alignment files | Binomial model of clipped reads at exon boundaries | Specifically designed for cDNA contamination; outperforms Vecuum [28] |

| DeconSeq [29] | Removing sequence contamination (e.g., human) from genomic/metagenomic data | Raw reads (longer-read, >150bp) | Alignment to reference contaminant genomes | Robust framework with graphical visualization; web and standalone versions [29] |

| Custom Pipeline [30] | Cleaning eukaryotic pathogen draft genomes | Genome assemblies | Alignment of pseudo-reads to host/contaminant databases | Effectively reduces false positives in pathogen diagnosis [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Protocol 1: Prevalence-Based Contamination Identification withdecontam

This protocol is ideal for amplicon sequencing studies (e.g., 16S rRNA) where negative controls have been sequenced.

1. Sample and Data Preparation:

- Generate an Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) or Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) table from your sequencing data using a standard pipeline (e.g., QIIME2, DADA2).

- Prepare a sample metadata sheet that includes a column (e.g.,

is_neg_control) marking which samples are true biological samples and which are negative controls.

2. Running decontam in R:

3. Interpretation:

- The

decontamalgorithm performs a chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test for small sample sizes) on the presence-absence table of each sequence feature between true samples and negative controls. A low P-value indicates the feature is significantly more prevalent in controls and is thus classified as a contaminant [27].

Protocol 2: Contaminant Detection and Removal in Genome Assemblies withContScout

This protocol is for removing contaminant sequences from annotated eukaryotic genome assemblies.

1. Prerequisites:

- Software: Install

ContScoutvia its Docker container for easy deployment. - Input Data: An annotated genome file in GFF3 or GenBank format, containing the predicted protein sequences.

- Database: Download and format a reference protein database (e.g., UniRef100).

2. Execution:

- The typical command to run

ContScoutinvolves pointing it to your input files and the database. (Refer to theContScoutGitHub repository for the exact command syntax). ContScoutfirst classifies each predicted protein via a similarity search against the reference database usingDIAMONDorMMseqs2[26].- It then assigns a consensus taxonomic label to each contig based on the classifications of its encoded proteins. Contigs where the majority of labels disagree with the target organism are marked for removal [26].

3. Output:

- The primary output is a "clean" genome file with contaminant contigs removed.

- It also provides a detailed report of which sequences were removed and their predicted taxonomic origin, which is crucial for manual validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key resources used in the experiments and methods cited in this guide.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FloqSwabs (Copan) [3] | Sterile swab for microbial surface sampling | Collecting microbiome samples from interior surfaces of habitat modules (MDRS study) [3] |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) [3] | DNA extraction from environmental and difficult soil samples | Extracting DNA from swab pellets and soil samples for 16S rRNA sequencing [3] |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [3] | A balanced salt solution for suspending and rinsing cells | Moistening swabs for sample collection and resuspending pellets during DNA extraction [3] |

| Modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium (mGAM) [31] | A rich growth medium for cultivating gut bacteria | Used in pairwise co-culture experiments to study bacterial interaction patterns [31] |

| UniRef100 Database [26] | A comprehensive database of non-redundant protein sequences | Used as a reference for protein-based taxonomic classification in ContScout [26] |

| Illumina MiSeq Platform [3] [32] | A bench-top sequencer for targeted and small genome sequencing | Used for 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing in multiple studies [3] [32] |

| 1,3,2-Benzothiazagermole | `1,3,2-Benzothiazagermole|[State Core Research Use]` | 1,3,2-Benzothiazagermole is a high-purity reagent for research applications in [e.g., materials science]. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Barium di(ethanesulphonate) | Barium di(ethanesulphonate), CAS:74113-46-5, MF:C4H10BaO6S2, MW:355.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Method Selection and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a conceptual workflow for selecting and applying decontamination methods based on the data type and available controls.

In the analysis of microbial community data, batch effects represent a significant source of technical variation that can confound biological signals and compromise research validity. These unwanted variations arise from technical sources such as different sequencing platforms, reagent lots, handling personnel, or processing dates [33] [34]. In the context of noise reduction for microbial community data analysis, effective batch effect correction is essential for distinguishing true biological variation from technical artifacts, thereby ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of research findings.

This technical support center document provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions to assist researchers in addressing specific challenges encountered during batch effect correction workflows. The content is structured to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in implementing robust batch effect correction strategies tailored to microbiome data analysis.

FAQ: Understanding Batch Effects

What are batch effects and how do they arise in microbiome studies? Batch effects are technical, non-biological factors that introduce unwanted variation in high-throughput data. In microbiome studies, they arise from differences in experimental conditions across samples processed at different times, locations, or using different protocols. Technical factors include variations in DNA extraction efficiency, PCR amplification bias, sequencing depth, and different handling personnel [33] [34]. These effects can confound true biological signals, leading to spurious findings if not properly addressed.