Compositional Data Analysis in Microbiome Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Application

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for handling the compositional nature of microbiome data.

Compositional Data Analysis in Microbiome Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for handling the compositional nature of microbiome data. Covering foundational principles of compositional data analysis (CoDA), we explore established and emerging methodological approaches, address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world data challenges, and present validation frameworks for comparing differential abundance methods. With the global microbiome market projected to reach $1.52 billion by 2030, mastering these analytical techniques is increasingly crucial for developing robust biomarkers and therapeutics across gastrointestinal diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders.

Understanding Compositional Data: Why Microbiome Analysis Demands Specialized Approaches

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Compositional Data Fundamentals

FAQ 1: What makes microbiome data "compositional"? Microbiome data are compositional because the data obtained from sequencing—such as counts of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs)—are constrained to sum to the same total (e.g., the total number of sequences per sample, known as the library size). This means the data only convey relative information about the proportions of each taxon, not its absolute abundance in the original sample. The abundances are effectively parts of a whole that must sum to 1 (or 100%) [1] [2] [3].

FAQ 2: Why is ignoring compositionality problematic in data analysis? Ignoring the compositional nature of microbiome data can lead to spurious correlations and false-positive findings [2]. Because the data are constrained, an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon mathematically forces a decrease in the relative abundance of others, even if their absolute abundances remain unchanged. This creates interdependencies between features that violate the assumptions of standard statistical tests, which can result in misleading conclusions about differential abundance and microbial associations [4] [2] [3].

FAQ 3: What is the "closure problem" in compositional data? The closure problem refers to the artifact introduced when data are forced to sum to a constant. This constraint means that components do not vary independently. A true change in the absolute abundance of a single taxon will cause the relative proportions of all other taxa in the sample to shift, creating the illusion that they have changed when they may not have [2].

FAQ 4: How does compositionality affect the analysis of cross-sectional versus longitudinal studies? In cross-sectional studies, compositionality can bias comparisons between different groups of samples (e.g., healthy vs. diseased). In longitudinal studies, an additional challenge arises because samples measured at different times may represent different sub-compositions if the total microbial load changes over time. This makes it critical to use analytical methods that respect compositional properties across time points [5].

FAQ 5: Are sequencing count data from other fields, like transcriptomics or glycomics, also compositional? Yes. Any data generated by high-throughput sequencing that is subject to a total sum constraint is compositional. This includes transcriptomics data (bulk and single-cell RNA-seq) and comparative glycomics data, where relative abundances of glycans are measured. The same CoDA principles are being applied to these fields to ensure statistically rigorous analysis [6] [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Analytical Issues

Issue 1: My model performance is poor and I suspect overfitting due to high dimensionality.

- Potential Cause: Microbiome data often have thousands of features (taxa) but only tens or hundreds of samples. This "curse of dimensionality," combined with data sparsity, can easily lead to overfitted models that fail to generalize [1].

- Solution: Implement robust feature selection to identify a compact set of predictive taxa.

- Recommended Method: Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevancy (mRMR) or LASSO regression have been shown to be highly effective for microbiome data, offering a massive reduction in feature space while maintaining or improving model performance [1].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Normalize your data using a method like centered log-ratio (CLR).

- Apply a feature selection algorithm (e.g., mRMR or LASSO) within a nested cross-validation framework.

- Train your classifier (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest) on the reduced feature set.

- Validate performance on a held-out test set or via the outer loop of cross-validation, using metrics like AUC.

Issue 2: My differential abundance analysis is producing inconsistent or unreliable results.

- Potential Cause: Applying standard statistical tests (e.g., t-tests) directly to relative abundances or raw counts without accounting for compositionality.

- Solution: Use a differential abundance analysis (DAA) method designed for compositional data.

- Recommended Workflow:

- Apply a CoDA transformation such as Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) or Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) to your count data [4] [7].

- Consider group-wise normalization. Novel methods like Fold-Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) calculate normalization factors at the group level, which can better control the false discovery rate in challenging scenarios [8] [3].

- Run a CoDA-aware DAA method such as

coda4microbiome, which performs penalized regression on all possible pairwise log-ratios to identify microbial signatures [5].

- Recommended Workflow:

Issue 3: My data are full of zeros (sparse), and CoDA transformations cannot handle them.

- Potential Cause: Log-ratio transformations require non-zero values. Zeros, which can be due to biological absence or technical dropouts (common in both microbiome and scRNA-seq data), are a known challenge for CoDA [6].

- Solution: Employ a strategy to handle zeros before transformation.

- Approach 1 (Count Addition): Add a small, uniform value to all counts (a "prior") or use a sophisticated count addition scheme like the one implemented in the

CoDAhdR package for scRNA-seq, which may be adaptable to microbiome data [6]. - Approach 2 (Imputation): Use imputation methods (e.g., ALRA, MAGIC) to estimate the values of zeros, though this should be done cautiously [6].

- Approach 3 (Novel Transformations): For highly zero-inflated data, newer transformations like Centered Arcsine Contrast (CAC) and Additive Arcsine Contrast (AAC) may be more effective than CLR or ALR [7].

- Approach 1 (Count Addition): Add a small, uniform value to all counts (a "prior") or use a sophisticated count addition scheme like the one implemented in the

Comparative Data on Method Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Normalization Techniques and Their Impact on Classifiers [1]

| Normalization Method | Description | Recommended Classifier Pairing | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Normalizes data relative to the geometric mean of all features in a sample. | Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines | Improves model performance and facilitates feature selection. |

| Relative Abundances | Converts counts to proportions per sample. | Random Forest | Random Forest models yield strong results using relative abundances directly. |

| Presence-Absence | Converts data to binary (1 for present, 0 for absent). | All Classifiers (KNN, RF, SVM, etc.) | Achieved performance similar to abundance-based transformations across classifiers. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods [1]

| Feature Selection Method | Key Advantages | Computational Efficiency | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRMR (Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevancy) | Identifies compact, informative feature sets; performance comparable to top methods. | Moderate | High |

| LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) | Top results in performance; effective feature selection. | High (requires lower computation times) | High |

| Autoencoders | Can perform well with complex, non-linear patterns. | Low | Low (lacks direct interpretability) |

| Mutual Information | Captures non-linear dependencies. | Moderate | Moderate (can suffer from redundancy) |

| ReliefF | Instance-based feature selection. | Moderate | Struggles with data sparsity |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Basic CoDA Workflow for Cross-Sectional Studies

This protocol uses the coda4microbiome R package to identify a microbial signature for a binary outcome (e.g., disease status) [5].

- Data Preparation: Load your data as a matrix of counts or proportions (samples x taxa) and a vector of outcomes.

- Model Fitting: Use the

coda4microbiomefunction to fit a penalized logistic regression model on the "all-pairs log-ratio model." The algorithm internally:- Calculates all possible pairwise log-ratios between taxa.

- Performs

cv.glmnet(elastic-net penalized regression) to select the most predictive log-ratios.

- Signature Interpretation: The output is a microbial signature expressed as a balance between two groups of taxa: those with positive coefficients (associated with one outcome) and those with negative coefficients (associated with the other).

- Validation: The package provides functions to plot the signature's prediction accuracy and the selected taxa with their coefficients.

Protocol 2: Applying CoDA Transformations for Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering

This protocol is essential for visualizing and exploring microbiome data without the distortion of compositionality [4].

- Handle Zeros: Apply a chosen zero-handling method (e.g., count addition) to your raw count table.

- CLR Transformation: Transform the entire dataset using the CLR transformation. For a sample vector

x, CLR is calculated asclr(x) = log( x / g(x) ), whereg(x)is the geometric mean ofx. - Calculate Aitchison Distance: Compute the Aitchison distance matrix between samples. This is the Euclidean distance applied to the CLR-transformed data. It is the proper metric for compositional data.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Use the Aitchison distance matrix as input for:

- Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) for visualization.

- Clustering algorithms (e.g., hierarchical clustering). Studies have shown that clustering with Aitchison distance provides better separation of biological groups than using Euclidean distance on log-transformed relative abundances [4].

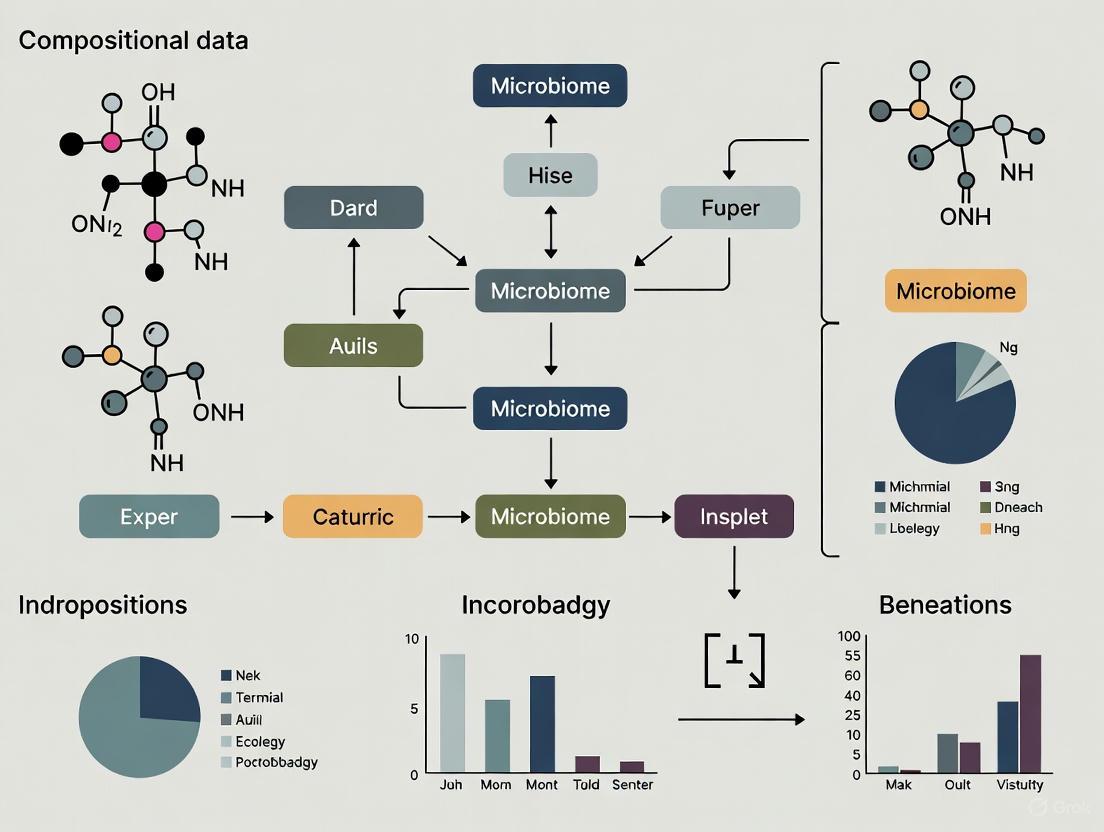

Visual Workflows and Logical Diagrams

CoDA-Based Differential Abundance Analysis Workflow

Diagram Title: CoDA-Based Differential Abundance Analysis Workflow

Feature Selection and Classification Pipeline for Microbiome Data

Diagram Title: Feature Selection and Classification Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Compositional Data Analysis

| Tool / Resource Name | Type / Function | Key Application in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome (R package) | Algorithm for microbial signature identification | Identifies predictive balances of taxa for both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies using penalized regression on log-ratios [5]. |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance analysis tool | Uses a Dirichlet-multinomial model to infer relative abundances and performs significance testing on CLR-transformed data, robust to compositionality [3]. |

| MetagenomeSeq | Differential abundance analysis tool | Often used with novel normalization factors like FTSS for improved false discovery rate control [8] [3]. |

| glmnet (R package) | Penalized regression | The engine for performing feature selection (via LASSO) within frameworks like coda4microbiome [5]. |

| CoDAhd (R package) | CoDA transformations for high-dim. data | Applies CoDA log-ratio transformations to high-dimensional, sparse data like scRNA-seq; methods may be adaptable to microbiome data [6]. |

| Aitchison Distance | A compositional distance metric | The proper metric for calculating beta-diversity and for use in ordination (PCoA) and clustering of compositional data [4]. |

| Center Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation | Core CoDA transformation | Normalizes data by the geometric mean of the sample, moving data from the simplex to Euclidean space for downstream analysis [1] [4]. |

| Cysteine peptide | Cysteine peptide, MF:C32H50N10O9S, MW:750.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SW203668 | SW203668, MF:C22H19N3O2S, MW:389.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What makes microbiome data "compositional," and why is this a problem for standard statistical tests?

Microbiome data, derived from sequencing technologies like 16S rRNA or shotgun metagenomics, are inherently compositional. This means the data represent relative abundances where the count of any single taxon is dependent on the counts of all others in the sample because the total number of sequenced reads per sample (library size) is arbitrary and non-informative [9] [10]. Standard statistical methods (e.g., t-tests, Pearson correlation) applied to compositional data can produce misleading or invalid results [9]. A key issue is spurious correlation, where an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon can artificially create the appearance of a decrease in others, even if their absolute abundances remain unchanged [10].

FAQ 2: My data has many zeros. What is the best way to handle this "zero-inflation"?

Zero-inflation, where a large proportion (often up to 90%) of the data are zeros, is a major characteristic of microbiome data [11] [12]. These zeros can be either true absences (the taxon is genuinely not present) or false zeros (the taxon is present but undetected due to technical limitations like insufficient sequencing depth) [11]. Simply ignoring these zeros or using a fixed pseudocount can introduce bias. Specialized statistical models that explicitly account for this zero-inflation, such as Zero-Inflated Gaussian (ZIG) models (e.g., in metagenomeSeq) or Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) models, are often recommended as they can model the two types of zeros separately [11] [13].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic data from a statistical perspective?

While both data types share challenges like compositionality and sparsity, key differences influence analytical choices:

- 16S rRNA Data: Typically used for taxonomic profiling. It is characterized by high dimensionality and is less precise at the species level. Statistical methods often focus on operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [11].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Data: Used for both taxonomic and functional profiling. It generally has even smaller sample sizes and can be more plagued by high levels of biological and technical variability compared to 16S data. Its zero-inflation is often more due to under-sampling, and its data structure is closer to RNA-seq data [9].

FAQ 4: How does the choice of normalization method impact my differential abundance results?

The normalization method you choose can drastically alter your biological conclusions. A large-scale comparison of 14 differential abundance methods across 38 datasets found that different tools identified drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa [14]. For instance, some methods like limma-voom and Wilcoxon test on CLR-transformed data tended to identify a larger number of significant taxa, while others like ALDEx2 were more conservative [14]. The performance of these methods can also be influenced by data characteristics such as sample size, sequencing depth, and library size variation between groups [14] [10]. Therefore, using a consensus approach based on multiple methods is recommended to ensure robust interpretations [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Inconsistent or Unreliable Differential Abundance Results

Problem: You are running differential abundance analysis, but the list of significant taxa changes dramatically when you use a different method or normalization.

Solution:

- Diagnose Data Characteristics: Before analysis, assess your data's key features:

- Library Size Variation: Calculate the total reads per sample. A large variation (e.g., 10x difference between the smallest and largest library) can severely bias many methods [10].

- Sparsity: Calculate the percentage of zeros in your OTU/ASV table. High sparsity (>70-90%) requires methods robust to zero-inflation [12].

- Apply Compositional Data-Aware Methods: Avoid standard tests on raw or rarefied counts. Instead, use methods designed for compositionality. Empirical evaluations suggest the following for control of false discoveries:

- Use a Consensus Approach: Do not rely on a single method. Run multiple methods from different classes (e.g., a compositional method like

ALDEx2, a model-based method likeDESeq2oredgeRwith care, and a non-parametric method on CLR data) and compare the results. Taxa that are consistently identified across multiple methods are more reliable [14]. - Consider Data Filtering: Apply a prevalence filter (e.g., retain only taxa present in at least 10% of samples) to remove rare taxa that can contribute to noise and false discoveries. Note that this filtering must be independent of the test statistic [14].

Table 1: Common Differential Abundance Methods and Their Key Characteristics

| Method | Underlying Principle | Handles Compositionality? | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM/ANCOM-II [14] [10] | Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) | Yes | Conservative; can have lower sensitivity. |

| ALDEx2 [14] | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Yes | Uses a pseudocount; good FDR control. |

| DESeq2 [11] [14] | Negative Binomial Model | No* | Can be sensitive to library size differences and compositionality if not careful. |

| edgeR [11] [14] | Negative Binomial Model | No* | Can have a higher false discovery rate in some microbiome data benchmarks. |

| metagenomeSeq [11] | Zero-Inflated Gaussian (ZIG) | No* | Specifically models zero-inflation. |

| Wilcoxon on CLR [14] | Non-parametric on CLR | Yes | Can identify a high number of taxa; performance depends on CLR transformation. |

*Can be used with appropriate normalization but is not inherently compositional.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Batch Effects and Technical Variation

Problem: Your sample clusters or statistical results are driven more by technical factors (e.g., sequencing run, DNA extraction date) than by the biological conditions of interest.

Solution:

- Prevention in Design: Randomize samples from different experimental groups across sequencing runs and processing batches whenever possible.

- Visual Detection: Use ordination plots (PCoA, PCA) colored by the suspected batch variable. If samples cluster by batch, correction is needed.

- Statistical Correction: Employ batch effect correction methods. The choice depends on your experimental design and whether the batch is known.

- Important Note: Normalization alone is often insufficient to correct for batch effects. Dedicated batch correction methods are required, and their application should be validated to ensure biological signal is not removed [11].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: A Robust Workflow for Differential Abundance Analysis

This protocol outlines a method for identifying taxa that differ in abundance between two or more groups, while accounting for key data challenges.

Differential Abundance Analysis Workflow

Procedure:

- Quality Control & Filtering:

- Input: Raw OTU or ASV count table and sample metadata.

- Action: Remove samples with an extremely low number of reads (library size). Then, apply an independent prevalence filter to remove taxa that are rarely observed (e.g., those present in less than 10% of all samples) [14]. This reduces noise and computational burden.

- Normalization:

- Action: Choose a normalization technique to correct for uneven library sizes across samples. Do not use simple total sum scaling (converting to proportions) without further adjustment, as it reinforces the compositional structure.

- Common Choices:

- Differential Abundance Testing:

- Action: Apply multiple differential abundance methods from different statistical classes. As shown in Table 1, include at least one method that is inherently compositional (e.g.,

ALDEx2orANCOM-II).

- Action: Apply multiple differential abundance methods from different statistical classes. As shown in Table 1, include at least one method that is inherently compositional (e.g.,

- Consensus Analysis:

- Action: Compare the lists of significant taxa generated by the different methods. Prioritize taxa that are identified by multiple, methodologically distinct tools for downstream interpretation and validation [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Computational Tools for Microbiome Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 [11] | Software Package (R) | High-resolution processing of 16S rRNA data to infer exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). | Provides a more accurate alternative to OTU clustering. |

| QIIME 2 [11] | Software Pipeline | A comprehensive, user-friendly platform for processing and analyzing microbiome data from raw sequences. | Integrates many other tools and methods. |

| ALDEx2 [14] | Software Package (R) | Differential abundance analysis using a compositional data-aware Bayesian approach. | Good control of false discovery rate; uses CLR transformation. |

| ANCOM(-II) [14] [10] | Software Package (R) | Differential abundance analysis based on log-ratios, designed for compositional data. | Known for being conservative, leading to fewer false positives. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR [11] [14] | Software Package (R) | Generalized linear models for differential abundance analysis (negative binomial). | Use with caution; ensure proper normalization and be aware of compositionality limitations. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Data Transformation | Transforms compositional data to a Euclidean space for downstream analysis. | Requires handling of zeros (e.g., with a pseudocount) prior to transformation [14]. |

| GMPR Normalization | Normalization Method | A robust normalization method specifically designed for zero-inflated microbiome count data [12]. | Can be more effective than TSS or rarefying for sparse data. |

| Ramiprilat-d5 | Ramiprilat-d5, MF:C21H28N2O5, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Magnolignan I | Magnolignan I, MF:C33H30O6, MW:522.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Microbiome data, generated by high-throughput sequencing technologies, are fundamentally compositional [15]. This means that the data convey relative, not absolute, abundance information. Each sample is constrained by a fixed total (the total number of sequences obtained), meaning that an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon must be accompanied by a decrease in the relative abundance of one or more other taxa [5] [15]. Ignoring this compositional nature is a critical mistake that can lead to spurious correlations and misleading results [5] [15]. The approach pioneered by John Aitchison, known as Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA), provides a robust mathematical framework to correctly handle this relative information using log-ratios of the original components [16]. This guide addresses frequent challenges and provides troubleshooting advice for researchers applying CoDA principles to microbiome datasets.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why are my microbiome data considered compositional, and why is this a problem?

- Problem: Many standard statistical tests assume data are unconstrained and can vary independently. Researchers often apply these tests directly to relative abundance or raw count data from sequencing, unaware of the pitfalls.

- Solution: Understand that high-throughput sequencing data are compositional because the total number of counts per sample is arbitrary and fixed by the sequencing instrument. Only the relative abundances of the features (e.g., taxa) are informative [15]. Analyzing this data with standard correlation methods can produce false positives. The core problem is illustrated below: the absolute abundance in the environment is lost during sequencing, and only proportions are observed. A perceived increase in one taxon may be due to an actual increase in its absolute abundance, or a decrease in others.

FAQ 2: What is the fundamental principle behind the CoDA solution?

- Problem: Researchers struggle to move from absolute to relative thinking.

- Solution: The CoDA framework solves the compositionality problem by analyzing the data in terms of log-ratios between components (taxa) [5] [16]. A log-ratio is invariant to the total sum constraint; doubling the total number of counts in a sample does not change the log-ratio between any two taxa. This makes log-ratios a valid basis for statistical analysis. Aitchison's original approach used simple pairwise log-ratios, while subsequent developments introduced more complex transformations like the isometric log-ratio (ilr) [16]. A reappraisal of the field suggests that for most practical purposes, simpler pairwise log-ratios are sufficient and easier to interpret [16].

FAQ 3: How should I handle zeros in my data before log-ratio transformation?

- Problem: Log-ratios cannot be calculated when a component has a zero value, as division by zero is undefined. Zeros are common in microbiome data.

- Solution: Zero replacement is a common, though complex, preprocessing step. Simple replacements like adding a small pseudo-count to all values can be used but may distort the data structure. More sophisticated methods, such as Bayesian-multiplicative replacement, are often recommended as they better preserve the multivariate relationships in the data. Alternatively, some modern methods use power transformations (a type of Box-Cox transform) that can handle zeros without the need for replacement [16].

FAQ 4: What is a microbial signature in the CoDA context, and how is it found?

- Problem: Researchers want to identify a minimal set of predictive taxa (a microbial signature) for a disease or condition, but standard differential abundance tests can be confounded by compositionality.

- Solution: Within the CoDA framework, a microbial signature is identified through penalized regression (like LASSO or elastic net) on a model containing all possible pairwise log-ratios [5]. The resulting signature is expressed as a balance—a weighted log-contrast model where the sum of the coefficients is zero, ensuring compositional invariance [5]. For example, a signature might be:

Signature Score = 0.8 * log(Taxon_A / Taxon_B) - 0.5 * log(Taxon_C / Taxon_D). This balance discrimates between, for instance, cases and controls.

FAQ 5: How do I analyze longitudinal microbiome data with CoDA?

- Problem: In longitudinal studies, samples from different time points may represent different sub-compositions, making analysis particularly challenging.

- Solution: For longitudinal data, the trajectory of each pairwise log-ratio over time is calculated for each sample. A summary of this trajectory, such as the Area Under the Curve (AUC), is then used as the input for a penalized regression model to identify a dynamic microbial signature [5]. This signature will highlight groups of taxa whose log-ratio trajectories differ between study groups over time.

Essential Workflow for CoDA in Microbiome Studies

The following diagram outlines a standard CoDA-based workflow for cross-sectional microbiome studies, contrasting it with a problematic traditional path.

Research Reagent Solutions: A CoDA Toolkit

The table below lists key statistical tools and conceptual "reagents" essential for conducting CoDA on microbiome data.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for CoDA-based Microbiome Analysis

| Research Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log-ratio Transform | Data Transformation | Converts relative abundances into valid, real-space coordinates for analysis [5]. | Choice of type (e.g., CLR, ILR, ALR, pairwise) depends on context and interpretability [16]. |

| coda4microbiome R package | Software Package | Identifies microbial signatures via penalized regression on all pairwise log-ratios for cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [5]. | Signature is expressed as an interpretable balance between two groups of taxa. |

| ALDEx2 | Software Package | Uses a Dirichlet-multinomial model to infer true relative abundances and identifies differential abundance using a CLR-based approach. | Robust to the sampling variation and compositionality. |

| ANCOM | Software Package | Tests for differentially abundant taxa by examining the stability of log-ratios of each taxon to all others. | Reduces false positives due to compositionality but can be conservative. |

| Zero Replacement Algorithm | Data Preprocessing | Imputes values for zero counts to allow for log-ratio calculation. | Choice of method (e.g., Bayesian-multiplicative) can significantly impact results. |

| Phylogenetic Tree | Data Resource | Enables the use of phylogenetic-aware log-ratio transformations and distances. | Improves biological interpretability by accounting for evolutionary relationships. |

| Carmaphycin-17 | Carmaphycin-17, MF:C40H45N5O5, MW:675.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cnidicin (Standard) | Cnidicin (Standard), CAS:14348-21-1, MF:C21H22O5, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Scenarios with CoDA Principles

| Experimental Scenario | Common Pitfall | CoDA-Based Solution | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Abundance | Using t-tests/Wilcoxon tests on relative abundances. | Use log-ratio based methods like ALDEx2, ANCOM, or the balance approach in coda4microbiome [5]. | [5] |

| Correlation & Network Analysis | Calculating Pearson/Spearman correlation on raw counts or proportions, leading to spurious correlations. | Use proportionality (e.g., propr R package) or compute correlations on CLR-transformed data, acknowledging the compositionality. |

[15] |

| Longitudinal Analysis | Analyzing each time point independently and ignoring the compositional trajectory. | Model the AUC of pairwise log-ratio trajectories over time using a penalized regression framework [5]. | [5] |

| Clustering & Ordination | Using Euclidean distance on normalized counts for PCoA. | Use Aitchison's distance (Euclidean distance after CLR transformation) or other compositional distances for ordination. | [15] [16] |

In targeted microbiome sequencing, data is processed into units that represent microbial taxa. For years, the standard approach has been Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), which cluster sequences based on a similarity threshold, typically 97% [17] [18]. A more recent method uses Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), which are exact biological sequences inferred after correcting for sequencing errors, providing single-nucleotide resolution [17] [19] [20].

The choice between these methods is not merely technical; it fundamentally influences the compositional nature of the resulting data. Microbiome data is inherently compositional because sequencing yields relative abundances rather than absolute counts—the increase of one taxon necessarily leads to the apparent decrease of others [5] [21]. This compositional structure means that analyses focusing on raw abundances can produce spurious results, as the data carries only relative information [5] [21]. The shift from OTUs to ASVs refines the units of analysis, but also intensifies the challenge of correctly interpreting their interrelationships.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting for Researchers

Q1: What is the fundamental practical difference between an OTU and an ASV in my dataset?

An OTU is a cluster of similar sequences, typically grouped at a 97% identity threshold. It represents a consensus of similar sequences, blurring fine-scale biological variation and technical errors into a single unit [17] [18]. In contrast, an ASV is an exact sequence. Algorithms like DADA2 or Deblur use an error model specific to your sequencing run to distinguish true biological sequences from PCR and sequencing errors, resulting in a table of exact, reproducible sequence variants [17] [20] [18].

Q2: My analysis requires comparing results across multiple studies. Which approach is better?

ASVs are superior for cross-study comparison. Because ASVs are exact DNA sequences, they are directly comparable between studies that target the same genetic region [17] [19] [18]. OTUs, however, are study-specific; the same sequence may be clustered into different OTUs in different analyses depending on the other sequences present and the clustering parameters used [17] [22]. This makes meta-analyses using OTU data challenging and less reproducible.

Q3: I am studying a novel environment with many unknown microbes. Should this influence my choice?

Yes. In a novel environment where many taxa are not present in reference databases, a closed-reference OTU approach (which clusters sequences against a reference database) is inappropriate, as it will discard novel sequences [17]. In this scenario, de novo OTU clustering or an ASV approach is more suitable. The ASV method is particularly advantageous here because it does not rely on a reference database for its initial definition, retains all sequences, and produces units that can be easily shared and compared as new references become available [17].

Q4: I am seeing an unexpectedly high number of microbial taxa in my ASV table. What could be the cause?

This is a known risk of the ASV approach. A single bacterial genome often contains multiple, non-identical copies of the 16S rRNA gene. ASVs can resolve these intragenomic variants, potentially artificially splitting a single genome into multiple units [23]. One study found that for a genome like E. coli (with 7 copies of the 16S rRNA gene), a distance threshold of up to 5.25% is needed to cluster its full-length ASVs into a single unit with 95% confidence [23]. This "oversplitting" can inflate diversity metrics and must be considered when interpreting results.

Comparative Analysis: OTUs vs. ASVs at a Glance

The following table summarizes the key operational and practical differences between OTU and ASV methodologies.

| Feature | Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) | Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Clusters of sequences based on a similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) [17] [18] | Exact biological sequences inferred after error correction [17] [19] |

| Resolution | Coarser; variations within the threshold are collapsed [19] | Fine; distinguishes single-nucleotide differences [17] [20] |

| Reproducibility | Low; clusters are specific to a dataset and parameters [17] | High; exact sequences are directly comparable across studies [17] [18] |

| Primary Method | Clustering (de novo, closed-reference, open-reference) [17] | Denoising (error modeling and correction) [17] [20] |

| Dependence on Reference Databases | Required for closed-reference clustering [17] | Not required for initial inference; used for taxonomy assignment [17] |

| Handling of Novel Taxa | De novo clustering retains them; closed-reference loses them [17] | Retains all sequences, including novel ones [17] |

| Risk of Splitting Genomes | Lower; intragenomic variants are often clustered together [23] | Higher; can split different 16S copies from one genome into separate ASVs [23] |

| Common Tools | VSEARCH, mothur, USEARCH [22] [18] | DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE [17] [19] [18] |

Workflow Diagrams: From Raw Data to Compositional Units

The journey from raw sequencing reads to an ecological unit is a critical pathway that defines the structure of your compositional data. The two main pathways are visualized below.

OTU Clustering Workflow

ASV Inference Workflow

Successful microbiome analysis relies on a suite of bioinformatic tools and reference materials. The table below lists key resources for handling OTU and ASV data.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Compositional Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 [17] [20] [18] | R Package | Infers exact ASVs from amplicon data via denoising. | Produces the high-resolution, countable units that form the basis for robust compositional analysis. |

| QIIME 2 [20] [18] | Software Platform | Integrates tools for entire microbiome analysis workflow (supports both OTUs & ASVs). | Provides plugins for compositional transformations and downstream analysis, ensuring a coherent pipeline. |

| Deblur [19] [20] [18] | Algorithm / QIIME 2 Plugin | Rapidly resolves ASVs using a fixed error model. | An alternative to DADA2 for generating the exact units required for compositional methods. |

| VSEARCH [22] [18] | Software | Open-source tool for OTU clustering via similarity. | Generates traditional OTU data, which must then be treated as compositional. |

| SILVA [22] [20] | Reference Database | Provides curated, aligned rRNA gene sequences for taxonomic classification. | Essential for assigning taxonomy to both OTUs and ASVs, providing biological context to the compositional units. |

| Greengenes [22] [20] | Reference Database | A curated 16S rRNA gene database and taxonomy reference. | Another primary resource for taxonomic assignment of compositional features. |

| coda4microbiome [5] | R Package | Identifies microbial signatures using penalized regression on pairwise log-ratios. | Directly implements a CoDA framework for finding predictive balances in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. |

Navigating Compositional Challenges in Downstream Analysis

The move from OTUs to ASVs does not eliminate the compositional nature of microbiome data; it refines it. The fundamental principle remains: microbiome sequencing data reveals relative abundances, not absolute counts [21]. Ignoring this can lead to spurious correlations and incorrect conclusions [5] [21].

Best Practices for Robust Analysis:

- Embrace Log-ratios: Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) is based on log-ratios of abundances [5] [21]. Using log-ratios extracts the relative information between components, which is the valid information in your dataset. Tools like

coda4microbiomeuse this principle to identify microbial signatures as balances between groups of taxa [5]. - Be Cautious with Diversity Metrics: Alpha and beta diversity metrics should be chosen with an understanding of their behavior with compositional data.

- Contextualize ASV "Oversplitting": When using ASVs, be aware that the high resolution can artificially split genomes due to intragenomic variation [23]. If your ecological question operates at the species or genus level, it may be valid to aggregate ASVs post-inference to a higher taxonomic rank to mitigate this issue.

- Choose Your Pipeline for Your Question: For studies of well-characterized environments (e.g., human gut) where comparison to existing references is key, both OTUs and ASVs can yield similar ecological conclusions [22]. For novel environments or when seeking strain-level variation, ASVs provide a more reproducible and detailed foundation [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "compositional data" mean in the context of microbiome research? Microbiome data is compositional because the relative abundance of one taxon impacts the perceived abundance of all others. If dominant features increase, the relative abundance (proportion) of other features will decrease, even if their absolute abundance remains constant [24]. This fundamental property means that changes in one part of the community can create illusory changes in other parts.

Q2: What are the main analytical challenges posed by compositional data? The three primary challenges are:

- Library size variation: Significant differences in sequencing depth between samples require appropriate normalization before meaningful statistical analysis [24]

- Data sparsity: Many zeros in abundance tables due to undersampling or genuine absence [24]

- Compositional nature: Relative abundance measurements create dependencies between taxa, making traditional statistical methods inappropriate [24]

Q3: What tools can help researchers account for compositionality? MicrobiomeAnalyst provides multiple normalization methods specifically designed for compositional data in its Marker-gene Data Profiling (MDP) and Shotgun Data Profiling (SDP) modules [24]. The platform includes 19 statistical分æžå’Œå¯è§†åŒ–方法 that address compositional constraints.

Q4: How does compositionality affect differential abundance testing? Standard statistical tests assume independence between measurements, which violates the principles of compositional data. Without proper normalization methods designed for compositionality, you may identify false positives or miss genuine differences because changes appear relative rather than absolute [24].

Q5: Can I avoid compositionality issues by using absolute quantification methods? Yes, methods like qPCR absolute quantification and spike-in internal standards can complement relative abundance data by providing total microbial load, helping infer absolute species concentrations [25]. However, these approaches require additional experimental work and have their own technical considerations.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Apparent Biological Effects Driven by Compositionality Rather Than True Change

Symptoms:

- Inverse patterns between taxa that seem biologically implausible

- Effects disappear when using compositionally-aware methods

- Correlations that align with compositionality artifacts rather than biological expectations

Solutions:

- Apply appropriate normalization: Use methods designed for compositional data (e.g., CSS, log-ratio transformations) instead of traditional normalization [24]

- Incorporate absolute quantification: Combine 16S rRNA sequencing with qPCR to determine total bacterial load, then calculate absolute abundance using the formula: Absolute Abundance = Total Copy Number × Relative Abundance [25]

- Validate with multiple approaches: Compare results across different compositional data methods to ensure robust findings

- Use spike-in controls: Include internal standards during DNA extraction to normalize across samples [25]

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Different Analysis Tools

Symptoms:

- Different significance findings when using alternative tools

- Varying effect sizes across platforms

- Disagreement in feature selection

Solutions:

- Understand tool assumptions: Platforms like MG-RAST, VAMPS, Calypso, and MicrobiomeAnalyst have different underlying methodologies and normalization approaches [24]

- Check normalization defaults: Ensure you're using compositionally-appropriate normalization in each tool

- Compare R command history: MicrobiomeAnalyst provides transparency by displaying underlying R commands, improving reproducibility [24]

- Use standardized workflows: Follow established protocols like QIIME2 for consistent processing from raw data to analysis [26]

Problem: Handling Excessive Zeros in Abundance Data

Symptoms:

- Many zero values in feature tables

- Difficulty distinguishing biological zeros from technical zeros

- Sparse data causing model convergence issues

Solutions:

- Apply careful filtering: Remove low-abundance features, but preserve compositionality-aware methods [24]

- Use zero-imputation methods: Consider compositionally-appropriate zero replacement techniques

- Aggregate taxonomically: Group at higher taxonomic levels to reduce sparsity

- Validate findings: Ensure results aren't driven solely by zero patterns

Table 1: Microbial Absolute Quantification Methods Comparison

| Method | Principle | Data Output | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR Absolute Quantification | 16S universal primers quantify total bacterial load combined with relative abundance from sequencing [25] | Absolute species concentrations | Distinguishes true abundance changes from compositional effects; detects total load differences between conditions [25] | Requires additional experimental work; primer bias affects quantification |

| Spike-in Internal Standards | Known quantities of external DNA added before extraction [25] | Absolute abundance normalized to spike-ins | Controls for technical variation in extraction and sequencing; directly addresses compositionality | Choosing appropriate spike-ins; potential interference with native community |

| Relative Abundance Only | Standard amplicon sequencing without absolute quantification [24] | Relative proportions (percentages) | Standard methodology; requires only sequencing data | Susceptible to compositionality artifacts; cannot detect total load changes |

Table 2: Web-Based Tools for Microbiome Data Analysis

| Tool | Compositional Data Features | Normalization Methods | Unique Capabilities | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MicrobiomeAnalyst | Explicitly addresses compositionality in MDP and SDP modules [24] | Multiple compositional normalization options | Taxon Set Enrichment Analysis (TSEA); publication-quality graphics; R command history [24] | Cannot process raw sequencing data; no time-series analysis currently [24] |

| QIIME 2 | Pipeline includes compositionally-aware methods through plugins [26] | Various built-in and plugin normalization options | Extensive workflow from raw data to analysis; high reproducibility [26] | Steeper learning curve; requires command-line comfort [26] |

| Calypso | Includes some compositional data considerations | Standard normalization methods | User-friendly interface; diversity and network analysis [24] | Less transparent about underlying algorithms compared to MicrobiomeAnalyst [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: qPCR Absolute Quantification for 16S rRNA Studies

Purpose: Complement 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing with total bacterial load to infer absolute species concentrations in microbiome samples [25].

Materials Needed:

- Bacterial (16S) or fungal (ITS) universal primers

- qPCR system and reagents

- DNA samples

- Standard curve materials (genomic DNA or synthetic fragments)

Procedure:

- Perform qPCR with universal primers:

- Use domain-specific universal primers (16S for bacteria/archaea, ITS for fungi)

- Include standard curve with known copy numbers

- Calculate total 16S rRNA gene copies per sample

Conduct conventional amplicon sequencing:

- Perform standard 16S or ITS amplicon sequencing

- Process through standard QIIME2 [26] or similar pipeline

- Obtain relative abundance (%) for each taxon

Calculate absolute abundance:

- Apply the formula: Absolute Abundance = Total 16S rRNA Gene Copies × Relative Abundance [25]

- Use these absolute values for downstream statistical analysis

Validation: Test with mock communities of known composition to validate quantification accuracy [25].

Protocol 2: Compositionally-Aware Differential Abundance Analysis Using MicrobiomeAnalyst

Purpose: Identify genuinely differentially abundant taxa while accounting for data compositionality.

Materials Needed:

- Normalized feature table (from QIIME2, mothur, or similar)

- Sample metadata

- MicrobiomeAnalyst account (free)

Procedure:

- Data preparation and upload:

- Format feature table and metadata according to MicrobiomeAnalyst specifications [24]

- Upload to the MDP (Marker-gene Data Profiling) module

Data filtering and normalization:

- Apply low-count filtering based on data characteristics

- Select compositionally-appropriate normalization (CSS, TSS, etc.)

- Monitor data processing through the interactive interface [24]

Statistical analysis:

- Use built-in methods that account for compositionality

- Compare multiple approaches for robustness checking

- Download comprehensive results and R command history [24]

Interpretation: Focus on effects that persist across multiple compositionally-aware methods rather than relying on single approaches.

Methodological Workflows

Microbiome Analysis Workflow: Standard vs. Compositionally-Aware

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Compositional Data Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16S/ITS Universal Primers | Amplify target regions for sequencing and qPCR [25] | Select primers based on target taxa and region; validate with mock communities |

| qPCR Reagents and Standards | Quantify total bacterial load for absolute quantification [25] | Include standard curve in every run; optimize primer concentrations |

| Spike-in Internal Standards | External DNA controls for normalization [25] | Choose phylogenetically appropriate spikes; add before DNA extraction |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate microbial DNA from various sample types | Consistent efficiency critical; include extraction controls |

| Normalization Algorithms | Computational methods addressing compositionality [24] | CSS, log-ratio transformations; implement in R or specialized tools |

| Mock Community Standards | Validate entire workflow and quantification accuracy | Should represent expected community complexity; use for method validation |

| Celgosivir | Celgosivir, CAS:121104-96-9; 141117-12-6, MF:C12H21NO5, MW:259.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ML344 | ML344, MF:C13H19N5, MW:245.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

CoDA Methods in Practice: Transformations, Models, and Workflows for Robust Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are compositional data, and why do they require special treatment in microbiome analysis? Compositional data are vectors of non-negative elements that represent parts of a whole, constrained to sum to a constant (e.g., 1 or 100%) [27] [15]. In microbiome studies, sequencing data are compositional because the total number of counts (read depth) is arbitrary and fixed by the instrument [15]. Analyzing such data with standard Euclidean statistical methods can produce spurious correlations and misleading results, as an increase in one microbial taxon's relative abundance necessarily leads to a decrease in others [27] [2]. Log-ratio transformations are designed to properly handle this constant-sum constraint.

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between CLR, ALR, and ILR transformations? The core difference lies in the denominator used for the log-ratio and the properties of the resulting transformed data [27] [28].

- ALR (Additive Log-Ratio) uses a single, chosen taxon as the denominator for all other taxa. It is simple to interpret but is not isometric (it does not perfectly preserve Euclidean distances) [28].

- CLR (Centered Log-Ratio) uses the geometric mean of all taxa in a sample as the denominator. It is symmetric but produces transformed data that are collinear (sum to zero) [27] [29].

- ILR (Isometric Log-Ratio) constructs orthonormal coordinates by partitioning taxa into a series of sequential, binary balances. It is statistically elegant and isometric but can be complex to interpret as each coordinate represents a balance between groups of taxa rather than a single taxon [27] [29].

Q3: How do I choose the right log-ratio transformation for my analysis? The choice depends on your analytical goal, the need for interpretability, and data dimensionality. The following table summarizes key considerations:

Table 1: Guide for Selecting a Log-Ratio Transformation

| Transformation | Best Used For | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALR | Analyses with a natural reference taxon; when simplicity and easy interpretation are critical [28]. | Simple interpretation of log-ratios relative to a baseline [27] [28]. | Not isometric; result depends on the choice of reference taxon [27]. |

| CLR | Exploratory analysis like PCA; covariance-based methods; when no single reference taxon is appropriate [27] [30]. | Symmetric treatment of all taxa; suitable for high-dimensional data [27]. | Results in a singular covariance matrix, problematic for some statistical models [28]. |

| ILR | Methods requiring an orthonormal basis (e.g., standard parametric statistics); when phylogenetic structure can guide balance creation [29]. | Preserves exact Euclidean geometry (isometric); valid for most downstream statistical tests [27] [28]. | Complex interpretation of balances; many possible coordinate systems [27] [29]. |

Q4: My dataset contains many zeros. Can I still apply log-ratio transformations? Zeros pose a significant challenge since logarithms of zero are undefined. Common strategies include:

- Pseudo-counts: Adding a small positive value (e.g., 1 or 0.5) to all counts before transformation [31]. This is simple but can introduce bias [27] [31].

- Imputation: Replacing zeros with an estimated value using methods from packages like

zCompositions[2]. - Novel Transformations: For highly zero-inflated data, newer transformations like Centered Arcsine Contrast (CAC) and Additive Arcsine Contrast (AAC) have been developed as potential alternatives [7]. The best practice is to choose a strategy based on the assumed nature of the zeros (e.g., missing vs. true absence) and the specific transformation.

Q5: Do log-ratio transformations consistently improve machine learning classification performance? Recent evidence suggests that the performance gain is not universal. A 2024 study found that simple, proportion-based normalizations sometimes outperformed or matched compositional transformations like ALR, CLR, and ILR in classification tasks using random forests [29]. Furthermore, a 2025 study indicated that presence-absence transformation could achieve performance comparable to abundance-based transformations for classification, though the chosen transformation significantly influenced feature selection and biomarker identification [30]. Therefore, the optimal transformation may depend on the specific machine learning task and dataset.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Spurious Correlation Results

Problem: Your analysis reveals strong correlations between microbial taxa, but you suspect they may be artifacts of the compositional nature of the data.

Solution:

- Acknowledge Compositionality: Recognize that raw relative abundance or count data from sequencing are compositional. Never calculate correlations directly on raw proportions or counts [15] [2].

- Apply a Log-Ratio Transformation: Transform your data using CLR, ALR, or ILR before performing correlation analysis. This moves the data into a real-valued space where standard methods are more valid [27] [28].

- Use Compositionally Aware Methods: Consider methods specifically designed for compositional data, such as proportionality metrics (e.g.,

proprpackage) instead of correlation [15].

Diagnostic Diagram:

Issue 2: Choosing a Reference Taxon for ALR Transformation

Problem: The ALR transformation requires selecting a reference taxon, but no obvious biological baseline exists in your study.

Solution:

- Statistical Selection: For high-dimensional data, choose a reference taxon that maximizes the Procrustes correlation between the ALR geometry and the full log-ratio geometry, indicating a near-isometric result. As a secondary criterion, select a taxon with low variance in its log-transformed relative abundance to simplify interpretation [28].

- Prevalence and Abundance: Select a taxon that is highly prevalent (present in most samples) and has a stable, moderate-to-high abundance across samples to avoid instability from rare taxa.

- Biological Rationale: If applicable, use a taxon that is well-established as a common, stable core member in your study system (e.g., Faecalibacterium in gut microbiota studies).

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for CoDA Implementation

| Research Reagent (Software/Package) | Function | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 (R/Bioconductor) | Performs ANOVA-Like Differential Expression analysis for high-throughput sequencing data using a compositional data paradigm [32]. | Identifies differentially abundant features between groups while accounting for compositionality. |

| coda4microbiome (R package) | Provides exploratory tools and cross-sectional analysis to identify microbial balances associated with covariates [32]. | Discovers log-ratio signatures predictive of clinical or environmental variables. |

| PhILR (R package) | Implements the ILR transformation using a phylogenetic tree to guide the creation of balances [29]. | Leverages evolutionary relationships to construct interpretable orthonormal coordinates. |

| compositions (R package) | A comprehensive suite for compositional data analysis, providing CLR, ALR, and ILR transformations and related statistics [28]. | A general-purpose toolbox for core CoDA operations. |

| propr (R package) | Calculates proportionality as a replacement for correlation in compositional datasets [15]. | Measures association between parts in a compositionally valid way. |

Issue 3: Handling the Complexity of ILR Balances

Problem: You have applied an ILR transformation but find the resulting balance coordinates difficult to interpret biologically.

Solution:

- Use a Phylogenetic Guide: Employ a tool like the PhILR package, which uses a phylogenetic tree to create balances. This ensures that the balances represent splits between evolutionarily related groups, which are often more biologically meaningful than arbitrary partitions [29].

- Simplify Interpretation: Focus on balances with the largest variances or those that are most strongly associated with your experimental variables. Investigate the groups of taxa in the numerator and denominator of these key balances.

- Consider Alternative Log-Ratios: For a more intuitive model, use a Pairwise Log-Ratio (PLR) approach or the ALR transformation. While not strictly isometric, a carefully selected set of pairwise ratios can approximate the ILR geometry and be much easier to explain [27] [28].

Experimental Protocol: A Basic CoDA Workflow for Microbiome Data

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for analyzing amplicon sequencing data using Compositional Data Analysis.

1. Preprocessing and Input:

- Input Data: An OTU/ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) table from a pipeline like DADA2 or QIIME2 [33].

- Preprocessing: Perform basic filtering (e.g., removing taxa with very low prevalence). Address zeros via a chosen method (pseudo-count or imputation) [7] [31].

2. Core CoDA Transformation (Choose One):

- ALR Transformation:

- Methodology: Select a reference taxon

X_refbased on prevalence, abundance, or statistical criteria [28]. - Calculation: For each taxon

iin samplej, computelog(X_ij / X_refj). - Output: A matrix with

n-1transformed variables.

- Methodology: Select a reference taxon

- CLR Transformation:

- Methodology: Calculate the geometric mean

G_jof all taxa in samplej. - Calculation: For each taxon

iin samplej, computelog(X_ij / G_j). - Output: A matrix with

ntransformed variables that are collinear.

- Methodology: Calculate the geometric mean

- ILR Transformation (Phylogenetic):

- Methodology: Use the

philrfunction in R with a provided phylogenetic tree and abundance table [29]. - Output: A matrix of orthonormal balance coordinates.

- Methodology: Use the

3. Downstream Analysis:

- Use the transformed data for standard statistical procedures: PERMANOVA on Aitchison distances, PCA (on CLR-transformed data), linear models, or machine learning algorithms [27] [30].

Workflow Diagram:

High-throughput sequencing technologies, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, have become the foundation of microbial community profiling [34]. The data generated is compositional, meaning it carries only relative information, where an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon inevitably leads to a decrease in the relative abundance of others [5]. Ignoring this compositional nature is a primary source of spurious results and false discoveries in differential abundance (DA) analysis [34] [5]. This technical support guide is framed within a broader thesis on handling compositional data, providing researchers with practical, troubleshooting-focused protocols for implementing three robust tools—ALDEx2, ANCOM, and coda4microbiome—that are explicitly designed for this challenge.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

A. General Workflow and Theory

Q1: Why can't I use standard statistical tests like t-tests on raw microbiome count data? Microbiome data exists in a constrained space known as the Aitchison simplex. Using standard tests on raw or relative abundances violates the assumption of data independence, as the abundance of each taxon is dependent on all others. This often leads to an unacceptably high false discovery rate (FDR) [14] [5]. Compositional data analysis (CoDA) methods overcome this by reframing the analysis around log-ratios of counts, thus extracting meaningful relative information [34].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between the CLR and ALR transformations? The choice of log-ratio transformation is central to these tools.

- Centered Log-Ratio (CLR): Used by ALDEx2. It transforms the abundance of each taxon by dividing it by the geometric mean of all taxa in the sample. This avoids the need for a reference taxon but moves the data into a non-standard Euclidean space [34] [14].

- Additive Log-Ratio (ALR): Used by ANCOM. It transforms the abundance of each taxon by dividing it by the abundance of a chosen reference taxon. This is subject to consistency issues if the reference taxon is not stable across samples [34].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Featured Tools

| Tool | Core Methodology | Primary Function | Key Strength | Compositional Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | CLR Transformation & Bayesian Modeling | Differential Abundance Testing | Robust FDR control in benchmarking studies [34] [14]. | CLR |

| ANCOM | ALR Transformation & Statistical Testing | Differential Abundance Testing | Addresses compositionality without relying on distributional assumptions [35]. | ALR |

| coda4microbiome | Penalized Regression on All Pairwise Log-Ratios | Microbial Signature Identification | Focus on prediction and identification of minimal, high-power biomarkers [5]. | Agnostic (Works with CLR or ALR inputs) |

B. Tool-Specific Implementation and Diagnostics

ALDEx2

Q3: I'm getting unexpected results with ALDEx2. How do I ensure my R environment is configured correctly? ALDEx2 is an R package that requires a specific setup, especially when called from other environments like Python.

- Symptom: Errors during the

fit_model()call, such as"package 'ALDEx2' not found". - Solution:

- Install ALDEx2 in R directly:

if (!requireNamespace("BiocManager", quietly = TRUE)) install.packages("BiocManager") BiocManager::install("ALDEx2") - When using a wrapper (e.g., in the

scCODAPython package), you must explicitly provide the paths to your R installation, as shown in the documentation [35]:

- Install ALDEx2 in R directly:

Q4: How should I interpret the multiple columns of p-values in ALDEx2's output?

ALDEx2 produces several columns of p-values (we.ep, we.eBH, wi.ep, wi.eBH) corresponding to different statistical tests (Welch's t-test, Wilcoxon test) and their Benjamini-Hochberg corrected values [35]. It is standard practice to use the Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-values (we.eBH or wi.eBH) to control the False Discovery Rate. Consult the ALDEx2 documentation to select the test most appropriate for your data distribution.

ANCOM

Q5: ANCOM is not reporting any significant taxa, even when I expect it to. What could be wrong? ANCOM is known for its conservatism to control the FDR effectively [14].

- Symptom: The

"Reject null hypothesis"column returnsFALSEfor all taxa [35]. - Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Data Pre-processing: ANCOM can be sensitive to data sparsity. Consider applying an appropriate prevalence filter (e.g., retaining taxa present in at least 10% of samples) to remove uninformative zeros [14].

- Verify the Reference Taxon: The ALR transformation requires a reference taxon. While ANCOM automates this, its performance can be affected if no stable, abundant reference exists in the dataset [34].

- Confirm Expected Effect Size: Benchmarking shows that different DA tools perform better under different conditions. ANCOM may have lower sensitivity (power) in studies with small effect sizes or low sample sizes [14].

coda4microbiome

Q6: What is the difference between coda_glmnet and coda_glmnet_longitudinal, and when should I use each?

The coda4microbiome package provides separate functions for different study designs, a critical distinction often missed by users.

coda_glmnet: Use this for cross-sectional studies, where each subject provides a single microbiome sample. It performs penalized regression on all pairwise log-ratios from a single time point [36] [5].coda_glmnet_longitudinal: Use this for longitudinal studies, with repeated measures from the same subjects over time. It identifies dynamic microbial signatures by summarizing the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of log-ratio trajectories before performing penalized regression [36] [5].

Q7: How do I extract and interpret the final microbial signature from coda4microbiome? The signature is not just a list of taxa but a balance between two groups of taxa.

- Output: The function returns an object containing

taxa.name(the selected taxa) andlog-contrast coefficients(their weights) [36]. - Interpretation: The microbial signature score for a new sample is calculated as a weighted sum of the log-abundances, with the constraint that the coefficients sum to zero. This ensures the model is compositionally valid. The result can be visualized as a balance between taxa with positive coefficients and those with negative coefficients, providing a biologically interpretable signature [5].

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance Across 38 Datasets (Adapted from Nearing et al., 2022)

| Tool | Typical FDR Control | Relative Sensitivity | Key Finding from Large-Scale Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Good | Lower | Produces consistent results and agrees well with the intersect of results from different methods [14]. |

| ANCOM | Good | Lower | Identifies drastically different sets of significant taxa compared to other tools [14]. |

| Limma-voom / edgeR | Often High | High | Often identifies the largest number of significant ASVs, but with a high FDR [34] [14]. |

| coda4microbiome | Good (by design) | Varies | Focused on predictive performance and biomarker identification, not raw p-value counts [5]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Cross-Sectional Analysis Workflow

This protocol outlines a robust workflow for a case-control study using the three tools.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Raw Count Table | The foundational input data; a matrix of read counts (samples x taxa). |

| Sample Metadata | Data frame containing group assignments (e.g., Case/Control) and covariates (e.g., Age, BMI). |

| ALDEx2 R Package | Executes the CLR transformation and Bayesian differential abundance testing [35]. |

ANCOM (via scikit-bio or R) |

Performs differential abundance testing using the ALR transformation and FDR control [35]. |

| coda4microbiome R Package | Identifies a minimal microbial signature for prediction using penalized regression [36]. |

Methodology:

Data Pre-processing:

Parallel Tool Execution:

- ALDEx2 in R:

- ANCOM in Python (using scCODA wrapper):

- coda4microbiome in R:

Results Integration:

Longitudinal Analysis Workflow with coda4microbiome

This protocol is specific for analyzing time-series microbiome data.

Methodology:

- Data Structuring: Ensure your data is in "long format," with multiple rows per subject (one for each time point). The required arguments are

x(abundances),y(outcome),x_time(observation times), andsubject_id[36]. - Model Execution:

- Signature Interpretation: The resulting signature describes two groups of taxa whose log-ratio trajectories over the specified time window are associated with the outcome. The package provides functions to plot these trajectories for cases and controls [5].

By leveraging these troubleshooting guides and standardized protocols, researchers can confidently implement ALDEx2, ANCOM, and coda4microbiome, ensuring their findings are both statistically robust and biologically meaningful within the rigorous framework of compositional data analysis.

Understanding the distinction between cross-sectional and longitudinal studies is fundamental in microbiome research. A cross-sectional study provides a single microbial "snapshot" of a population at one specific point in time, ideal for identifying associations between the microbiome and health outcomes. In contrast, a longitudinal study collects multiple samples from the same subjects over time, enabling researchers to track dynamic changes in microbial communities in response to factors like diet, medical treatments, or disease progression [37] [38]. While cross-sectional designs have dominated early microbiome research due to their logistical simplicity, longitudinal designs are increasingly recognized as essential for understanding temporal dynamics, causal relationships, and the personalized nature of host-microbiome interactions [38].

A key challenge in analyzing data from both designs is their compositional nature, meaning the data represent relative proportions rather than absolute abundances. This characteristic requires specialized statistical approaches to avoid spurious results [5]. The following sections provide troubleshooting guidance, methodological frameworks, and practical solutions for implementing both study designs effectively.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our cross-sectional study found several microbial biomarkers. Why should we consider a more costly longitudinal follow-up? Cross-sectional analyses can identify associations but cannot determine causality or capture dynamic responses. Longitudinal studies reveal whether your biomarkers are stable or transient, whether they precede or follow disease onset, and how they respond to interventions. For example, while cross-sectional studies linked the vaginal microbiome to preterm birth, longitudinal analyses provided more sensitive insights into microbial signatures that change throughout pregnancy and are more predictive of birth timing [38].

Q2: How does the compositional nature of microbiome data affect our choice of analysis method? Microbiome data are compositional because they represent relative proportions constrained by a total sum. This means the observed abundance of each taxon is only informative relative to other taxa. Ignoring this compositionality can lead to spurious correlations and false discoveries. Methods specifically designed for compositional data, such as those utilizing log-ratio transformations, are essential for both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses [5].

Q3: Our longitudinal study shows high variability between subjects. How can we distinguish meaningful temporal patterns from noise? High inter-subject variability is common in microbiome studies. To address this:

- Use visualization methods that account for repeated measures, such as PCoA adjusted with linear mixed models (LMMs) to separate subject-specific effects from temporal trends [39].

- Employ longitudinal-specific statistical methods like GEE models or the

coda4microbiomepackage that are designed to handle within-subject correlations over time [40] [5]. - Ensure your study is sufficiently powered to detect effects of interest despite this variability [37].

Q4: What is the fundamental difference between analyzing cross-sectional versus longitudinal microbiome data? The key difference lies in handling within-subject dependency. Cross-sectional data assume independent samples, while longitudinal data must account for the correlation between multiple measurements from the same subject. This requires specialized methods that model these dependencies to avoid inflated false positive rates and enable the investigation of temporal dynamics [40] [5] [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inadequate Control of False Discovery in Differential Abundance Analysis

Problem: Your differential abundance analysis identifies many significant taxa, but you suspect a high false discovery rate or results don't validate in subsequent experiments.

Solutions:

- For Cross-Sectional Studies: Implement the

metaGEENOMEframework, which integrates Counts adjusted with Trimmed Mean of M-values (CTF) normalization and Centered Log Ratio (CLR) transformation. Benchmarking has shown this approach effectively controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR) while maintaining high sensitivity compared to tools like MetagenomeSeq, edgeR, and DESeq2 [40]. - For Longitudinal Studies: Use the

coda4microbiomeR package, which performs penalized regression on the area under the log-ratio trajectories. This method respects compositionality while leveraging the temporal dimension to identify robust dynamic signatures [5]. - General Best Practice: Always use compositionally aware methods. Standard statistical tests assuming independent data can produce spurious results with compositional microbiome data [5].

Issue 2: Visualizing Longitudinal Data Effectively

Problem: Standard Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots of your longitudinal data appear cluttered and fail to clearly show temporal trends.

Solutions:

- Implement the enhanced PCoA framework for repeated measures designs that adjusts for covariates and subject effects using Linear Mixed Models (LMMs) [39].

- Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Calculate the pairwise dissimilarity matrix using an ecologically relevant metric (e.g., Bray-Curtis, UniFrac).

- Transform the dissimilarity to a similarity matrix via Gower centering.

- Instead of plotting principal coordinates directly, adjust for confounding variables and repeated measures by fitting an LMM to each principal coordinate.

- Extract standardized residuals from the LMM to remove unwanted variation while preserving dependencies of interest.

- Reconstruct the similarity matrix using these residuals and perform PCoA on the adjusted matrix.

- Visualize the adjusted principal coordinates to reveal clearer temporal patterns [39].

Issue 3: Analyzing Microbial Interactions in Longitudinal Studies

Problem: You want to understand how microbial taxa interact over time in response to an intervention, but standard correlation methods are inadequate.

Solutions:

- Implement LUPINE (LongitUdinal modelling with Partial least squares regression for NEtwork inference), a novel method specifically designed for longitudinal microbiome studies [41].

- Key Advantages of LUPINE:

- Infers microbial networks sequentially, incorporating information from all previous time points.

- Captures dynamic microbial interactions that evolve over time, particularly useful during interventions like diet changes or antibiotics.

- Handles scenarios with small sample sizes and limited time points common in microbiome studies.

- Provides binary network graphs where edges represent significant conditional associations between taxa after accounting for other community members [41].

Methodological Frameworks & Experimental Protocols

Framework 1: Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) for Both Study Designs

The coda4microbiome package provides a unified CoDA approach for both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [5]:

Cross-Sectional Protocol:

- Model Construction: Fit a generalized linear model containing all possible pairwise log-ratios (the "all-pairs log-ratio model"):

g(E(Y)) = β₀ + Σβjk · log(Xj/Xk) - Variable Selection: Perform penalized regression (elastic-net) to identify the most predictive log-ratios.

- Signature Interpretation: The final microbial signature is expressed as a balance between two groups of taxa—those contributing positively versus negatively to the prediction.

Longitudinal Protocol:

- Trajectory Calculation: For each subject, compute the trajectories of pairwise log-ratios across all time points.

- Summary Metric: Calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of these log-ratio trajectories.

- Model Fitting: Perform penalized regression on the AUC values to identify dynamic microbial signatures.

- Signature Interpretation: Identify taxa groups with differential log-ratio trajectories between cases and controls.