Conquering PCR Bias in Amplicon Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Amplicon sequencing is a powerful tool in molecular biology, yet its quantitative accuracy is fundamentally challenged by PCR amplification bias.

Conquering PCR Bias in Amplicon Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Amplicon sequencing is a powerful tool in molecular biology, yet its quantitative accuracy is fundamentally challenged by PCR amplification bias. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, mitigating, and correcting these biases. We explore the foundational sources of bias from library preparation through sequencing, detail cutting-edge methodological improvements including novel polymerase formulations and computational corrections, offer practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for robust assay design, and validate these approaches through comparative analyses of sequencing platforms and protocols. The synthesized knowledge herein empowers scientists to generate more reliable and reproducible sequencing data, thereby enhancing the validity of findings in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Understanding the Enemy: Foundational Concepts and Sources of PCR Bias in Amplicon Sequencing

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a fundamental step in preparing DNA samples for high-throughput amplicon sequencing. However, PCR is an imperfect process that introduces multiple forms of bias, skewing the representation of the original microbial community in sequencing results. These biases originate at multiple stages of the experimental workflow, from sample preservation to final sequencing, and can significantly impact downstream analyses and biological interpretations. Understanding these sources of bias is crucial for researchers aiming to generate robust, reproducible microbiota data.

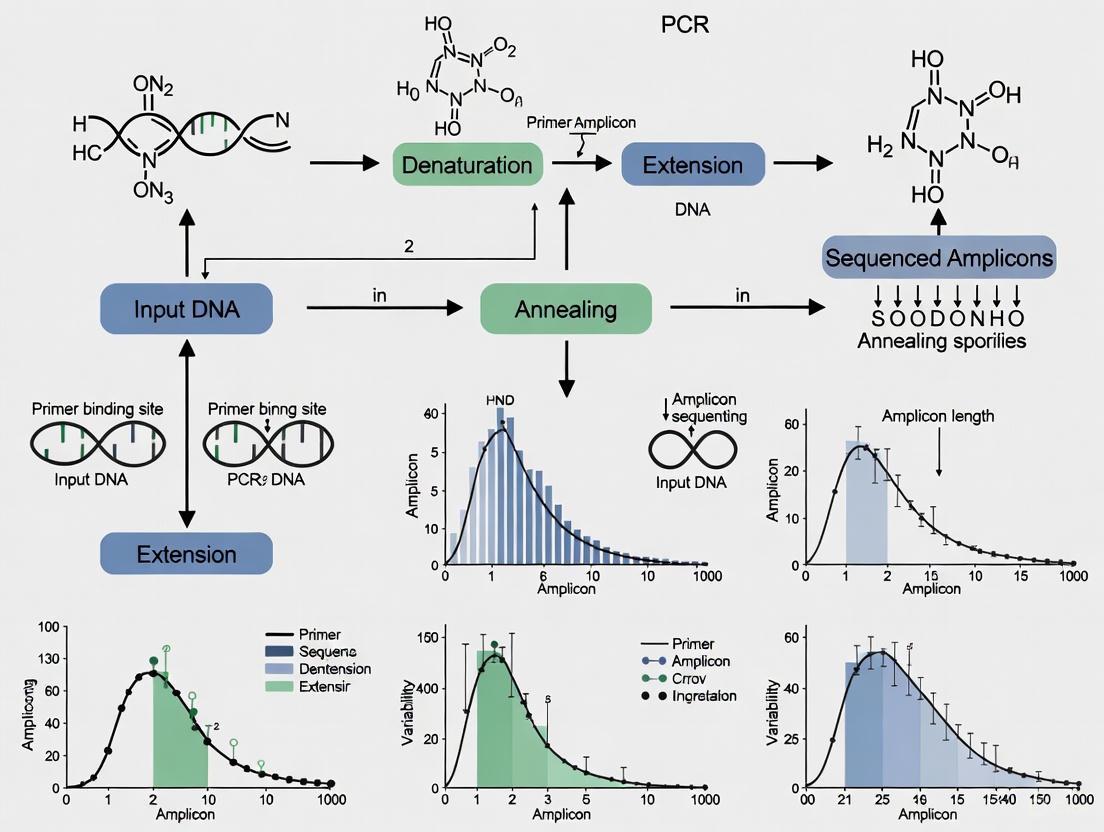

The following diagram illustrates the complete amplicon sequencing workflow and identifies key sources of bias at each experimental stage:

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Mitigating Bias at Each Stage

Sample Collection and Preservation Bias

Problem: Microbial community changes between sample collection and DNA extraction.

Question: How do different sample preservation methods affect the integrity of microbial community composition, and what is the optimal approach?

Answer: Sample preservation method significantly impacts microbial community representation. Immediate freezing at -80°C is considered the gold standard but presents logistical challenges for large-scale or remote studies [1].

Experimental Evidence:

- Comparison Study: A 2023 study compared immediate freezing with two stabilization buffers (OMNIgene·GUT and Zymo Research) stored at room temperature for 3-5 days [1].

- Findings: Stabilization buffers limited Enterobacteriaceae overgrowth compared to unpreserved samples but still showed differences from immediately frozen samples, with higher Bacteroidota and lower Actinobacteriota and Firmicutes abundance [1].

- Recommendation: For large-scale studies where cold chain maintenance is challenging, stabilization systems provide a acceptable compromise, though immediate freezing remains optimal [1].

DNA Extraction Bias

Problem: Differential cell lysis efficiency across microbial taxa.

Question: How does the DNA extraction method, particularly cell disruption technique, introduce bias in microbiome studies?

Answer: The method used for cell disruption is a major contributor to variation in microbiota composition, with mechanical methods generally providing more comprehensive lysis across diverse taxa [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Mechanical Disruption: Use repeated bead-beating with pre-assembled tubes containing 0.5g zirconia/silica beads (0.1mm) and five glass beads (2.7mm) [1].

- Sample Processing: Add 0.25g fecal material and 700μL S.T.A.R. buffer to beads, or 1mL of stabilization buffer for preserved samples [1].

- Validation: Compare mechanical vs. enzymatic lysis (using lysis buffer with Proteinase K at 95°C for 5min followed by 56°C incubation) on the same sample to assess efficiency [1].

- Result: Mechanical disruption typically recovers a more diverse representation of microbial taxa, particularly those with robust cell walls [1].

PCR Amplification Bias

Problem: Differential amplification of community DNA templates during PCR.

Question: What are the primary sources of PCR amplification bias, and how can they be minimized?

Answer: PCR amplification bias arises from multiple sources including primer-template mismatches, GC content, secondary structures, and stochastic effects, which can skew relative abundances up to fivefold [2] [3].

Quantitative Data on PCR Bias Sources:

Table 1: Relative Impact of Different PCR Bias Sources

| Bias Source | Impact Level | Cycle Phase Most Affected | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Stochasticity | High | Early cycles | Major force skewing sequence representation in low-input samples [3] |

| Primer-Template Mismatches | High | First 3 cycles | Single nucleotide mismatches can lead to preferential amplification up to 10-fold [4] |

| GC Content | Variable | Mid-late cycles | Depletes loci with GC content >65% to ~1/100th of mid-GC references [5] |

| Secondary Structures | Moderate-High | All cycles | Significant association between amplification efficiencies and secondary structure energy [2] |

| Polymerase Errors | Low (but cumulative) | Late cycles | Common in later cycles but confined to small copy numbers [3] |

| Template Switching | Low | Late cycles | Rare and confined to low copy numbers [3] |

Experimental Protocol for Bias Assessment:

- Calibration Experiment: Pool aliquots of extracted DNA from each study sample into a single calibration sample [4].

- Cycle Gradient: Split the calibration sample into aliquots and amplify each for a predetermined number of PCR cycles (e.g., 22, 24, 26, 28, 30 cycles) [2] [4].

- Sequencing and Modeling: Sequence all aliquots and use log-ratio linear models to infer initial composition and amplification efficiencies [4].

- Application: Apply derived correction factors to experimental samples amplified with standard cycles [4].

Primer-Related Bias

Problem: Inefficient or biased amplification due to primer-template mismatches.

Question: How do degenerate primers contribute to amplification bias, and what are the alternatives?

Answer: While degenerate primers are designed to increase coverage of diverse templates, they can substantially reduce reaction performance and introduce bias through inefficient annealing and primer depletion [6].

Experimental Evidence:

- Performance Comparison: A 2025 study compared degenerate vs. non-degenerate primers using qPCR and computational modeling [6].

- Findings: Non-degenerate primers produced amplicons significantly better than their degenerate counterparts when amplifying either consensus or non-consensus targets [6].

- Alternative Approach: "Thermal-bias PCR" uses only two non-degenerate primers with a large difference in annealing temperatures to isolate targeting and amplification stages, allowing proportional amplification of mismatched targets [6].

Sequencing Platform Bias

Problem: Platform-specific errors and representation bias.

Question: How do different sequencing platforms contribute to errors in amplicon sequencing data?

Answer: Different sequencing platforms exhibit distinct error profiles, with Illumina platforms predominantly showing substitution errors rather than the homopolymer errors characteristic of 454 pyrosequencing [7].

Experimental Evidence:

- Error Profile Analysis: A 2015 study analyzed error patterns across multiple library preparation methods and sequencing conditions [7].

- Platform Comparison: Illumina systems show substitution errors correlated with specific sequence patterns (inverted repeats and GGC sequences) and are affected by phasing/pre-phasing issues [7].

- Error Correction: Quality trimming combined with error correction (BayesHammer) followed by read overlapping (PANDAseq) reduces substitution error rates by an average of 93% [7].

Quantitative Data and Optimization Strategies

PCR Cycle Optimization

Quantitative Impact of PCR Cycles:

- Cycle Number Effect: Increasing from 20 to 25 PCR cycles can inflate UMI counts by 10-15% due to PCR errors being misinterpreted as unique molecules [8].

- Community Richness: Community richness decreases by approximately four-fold between cycles 10 and 15 alone in environmental DNA studies [4].

- Optimal Range: For 16S rRNA gene amplification, ~25 cycles is typically optimal, with higher cycles increasing contaminant detection in negative controls [1].

Table 2: PCR Optimization Strategies and Their Effects

| Optimization Strategy | Protocol Adjustment | Impact on Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Cycles | 25-30 cycles instead of 35-40 | Reduces late-cycle artifacts and polymerase errors [1] |

| Modified Denaturation | Extended denaturation (80s instead of 10s at 98°C) | Improves amplification of GC-rich templates [5] |

| Additives | 2M betaine | Reduces GC bias, stabilizes DNA denaturation [5] |

| Polymerase Selection | AccuPrime Taq HiFi instead of Phusion HF | Improves amplification evenness across GC spectrum [5] |

| Thermocycler Settings | Slower ramp speeds (2.2°C/s vs 6°C/s) | Allows more complete denaturation of GC-rich templates [5] |

| Input DNA | ~125pg input DNA | Reduces effect of contaminants while maintaining library complexity [1] |

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for Error Correction

Problem: PCR errors and amplification bias affecting molecular quantification.

Question: How can UMIs mitigate PCR amplification bias, and what are the limitations of current approaches?

Answer: UMIs distinguish original molecules before amplification, theoretically removing PCR biases, but PCR errors within UMIs themselves can lead to inaccurate molecular counting [8].

Experimental Evidence:

- Error Assessment: Increasing PCR cycles from 20 to 25 led to a substantial increase in errors within common molecular identifiers (CMIs), causing transcript overcounting [8].

- Novel Solution: Homotrimeric nucleotide blocks for UMI synthesis provide error correction through a 'majority vote' method, significantly improving accuracy [8].

- Performance: Homotrimeric correction achieved 98.45%, 99.64%, and 99.03% correct CMI calls for Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies platforms, respectively, outperforming monomer-based UMI-tools [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bias Mitigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Bias Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilization Buffers | OMNIgene·GUT, Zymo Research DNA/RNA Shield | Preserves microbial community structure at room temperature [1] |

| Mechanical Beads | Zirconia/silica beads (0.1mm) with glass beads (2.7mm) | Ensures efficient cell disruption across diverse taxa [1] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerases | AccuPrime Taq HiFi, Q5, Kapa HiFi | Reduces polymerase errors and improves amplification evenness [7] [5] |

| PCR Additives | Betaine, DMSO | Reduces GC bias and stabilizes DNA denaturation [5] |

| Non-Degenerate Primers | Targeted V4 16S rRNA primers | Improves amplification efficiency and reduces spurious products [6] |

| UMI Systems | Homotrimeric UMI designs | Enables correction of PCR and sequencing errors [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most impactful step I can take to reduce PCR bias in my amplicon sequencing workflow? A: Limiting PCR cycles to the minimum necessary for library detection (typically 25-30 cycles) has one of the most significant impacts, as late-cycle amplification exponentially increases stochastic effects and favors already-dominant templates [4] [1].

Q2: How can I determine if my observed community differences are biological or technical in origin? A: Implement a calibration experiment using pooled samples across a PCR cycle gradient [4], include replicate extractions and amplifications, sequence mock communities, and use positive controls throughout your workflow to distinguish technical variation from biological signals [1].

Q3: Are there computational methods to correct for PCR biases after sequencing? A: Yes, multiple computational approaches exist, including:

- Log-ratio linear models that use cycle gradient data to estimate and correct for taxon-specific amplification efficiencies [4].

- UMI-based error correction tools (e.g., UMI-tools, homotrimeric correction) that identify and collapse PCR duplicates [8].

- Denoising algorithms that correct PCR errors and identify biological sequences [2].

Q4: How does GC content specifically affect amplification efficiency? A: GC content influences denaturation efficiency (high-GC templates require more complete denaturation), primer binding stability, and secondary structure formation. Templates with GC content >65% can be depleted to 1/100th of mid-GC templates under standard conditions, but this can be mitigated with longer denaturation times and additives like betaine [5].

Q5: What is the recommended approach for sample preservation in large-scale epidemiological studies where immediate freezing is logistically challenging? A: DNA stabilization buffers such as OMNIgene·GUT or Zymo Research DNA/RNA Shield provide a practical compromise, limiting major community shifts while allowing room temperature storage and transportation [1]. However, researchers should validate their chosen method against immediate freezing for their specific sample type.

How does mRNA enrichment introduce bias in my RNA-seq data?

mRNA enrichment is a critical first step in many RNA-seq workflows and is a significant source of bias. The most common method uses oligo-dT beads to capture polyadenylated RNA. However, this method inherently introduces 3'-end capture bias, where coverage is dramatically skewed toward the 3' end of transcripts [9]. This bias can mask important biological information located in the 5' regions, such as alternative transcription start sites or upstream open reading frames (uORFs) [10].

Furthermore, oligo-dT-based enrichment is unsuitable for prokaryotic samples or degraded RNA, such as that from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues, as it requires intact poly(A) tails [9]. In these cases, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion is the preferred method. While rRNA removal mitigates the 3'-bias, its efficiency can vary across different RNA species, potentially leading to an underrepresentation of certain transcripts [9].

Table 1: mRNA Enrichment Methods and Associated Biases

| Enrichment Method | Principle | Primary Bias Introduced | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo-dT Selection | Hybridization to poly-A tail | Strong 3'-end bias; requires intact RNA | High-quality eukaryotic RNA; standard mRNA-seq |

| rRNA Depletion | Removal of ribosomal RNA | Variable efficiency across transcripts; less 3' bias | Prokaryotic RNA; degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE); whole-transcriptome analysis |

What are the consequences of RNA fragmentation bias?

Fragmentation is necessary to generate fragments of appropriate size for sequencing. The method of fragmentation can significantly impact the uniformity of sequence coverage. Early RNA-seq protocols often used RNase III for fragmentation, which is not completely random and can lead to reduced library complexity [9]. Biased fragmentation creates hotspots where fragments begin and end, which can be mistaken for biological signals and complicates the detection of splice variants and exact transcript boundaries [11].

To achieve more uniform coverage, it is recommended to use chemical treatment (e.g., zinc) for RNA fragmentation [9]. Alternatively, a more robust approach involves reverse transcribing intact RNA first and then fragmenting the resulting cDNA using mechanical or enzymatic methods [9]. This post-cDNA synthesis fragmentation helps generate more randomly distributed fragments.

How do priming strategies affect my sequencing results?

The choice of primers during reverse transcription and amplification is a major source of bias.

- Random Hexamer Priming: While designed to bind randomly across transcripts, random hexamers can anneal with varying efficiencies due to sequence context and secondary structure. This leads to uneven coverage along the transcript length and mispriming events [9] [10].

- Oligo-dT Priming: This method primes from the poly-A tail, resulting in strong 3' bias and poor coverage of the 5' ends of long transcripts [9] [10].

- Degenerate Primers: In amplicon sequencing, degenerate primer pools (containing mixed nucleotides) are used to amplify diverse templates. However, these pools can act as reaction inhibitors and are inefficient, paradoxically suppressing the amplification of both rare and consensus targets [6].

Experimental Solution: Thermal-Bias PCR A modern solution to priming bias is the "thermal-bias PCR" protocol, which uses only two non-degenerate primers in a single reaction. It exploits a large difference in annealing temperatures to separate the template targeting and library amplification stages, allowing proportional amplification of even mismatched targets [6].

Table 2: Priming Methods and Their Characteristics

| Priming Method | Common Use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo-dT | Reverse Transcription | Specific for poly-A+ RNA; simple | Strong 3' bias; unsuitable for degraded RNA |

| Random Hexamers | Reverse Transcription / Whole Transcriptome Amplification | Covers non-poly-A RNA; less 3' bias | Uneven coverage; mispriming; sequence-dependent bias |

| Degenerate Primers | Amplicon Sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA) | Theoretically broader taxonomic reach | Reduced overall efficiency; can inhibit amplification |

| Sequence-Specific | Targeted Amplicon Sequencing | High specificity | Limited to known target sequences |

What is the impact of PCR amplification on my differential expression analysis?

PCR amplification is a primary source of bias in sequencing library preparation, significantly impacting the accuracy of quantitative analyses like differential expression.

- Sequence-Dependent Bias: PCR does not amplify all sequences equally. Fragments with very high or very low GC content are often amplified less efficiently, leading to their underrepresentation in the final library [12] [13]. This can distort the true expression levels of these transcripts.

- Over-Amplification and Duplicates: Excessive PCR cycles lead to "overcycling," which increases artifacts, errors, and the rate of PCR duplicates [14] [15]. A critical point is that a large fraction of computationally identified duplicates are not PCR duplicates but natural duplicates caused by random sampling and fragmentation bias [11]. Therefore, the computational removal of all duplicates can actually worsen the accuracy of differential expression analysis by removing genuine biological information [11].

- Impact on Detection Power: Amplification bias adds technical noise, which reduces the statistical power to detect differentially expressed genes and can inflate the false discovery rate (FDR) [11].

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of PCR Amplification on RNA-seq Data

| Aspect | Impact of PCR Amplification | Consequence for Differential Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Under-representation of extreme GC content transcripts | Altered fold-change estimates for affected genes |

| Precision | Introduction of technical noise due to biased amplification | Reduced power to detect true differences |

| Duplicate Reads | Generation of PCR duplicates, but also loss of natural duplicates | Computational duplicate removal can worsen FDR |

What are the best practices to mitigate amplification bias?

Several strategies, both experimental and computational, can be employed to reduce the impact of amplification bias.

- Optimize PCR Components: The choice of DNA polymerase is critical. Studies have shown that enzymes like Kapa HiFi DNA Polymerase provide more uniform genomic coverage across a wide range of GC contents compared to other enzymes [12]. For extremely AT- or GC-rich templates, PCR additives like tetramethyleneammonium chloride (TMAC) or betaine can be used to improve amplification efficiency [9] [12].

- Minimize PCR Cycles: The most direct way to reduce PCR bias is to reduce the number of amplification cycles. Use the minimum number of cycles required to generate sufficient library yield [9] [14]. For high-input samples, consider PCR-free library preparation protocols [12].

- Utilize Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): UMIs are random oligonucleotide sequences that are added to each molecule before any amplification steps. This allows for the bioinformatic identification and correction of PCR duplicates, generating accurate, absolute counts of the original RNA molecules [11]. Recent advances include using homotrimeric nucleotide blocks to create UMIs with built-in error-correcting capabilities, which further improve the accuracy of molecule counting by mitigating PCR-associated sequencing errors [8].

- Employ Alternative Amplification Methods: For low-input and single-cell RNA-seq, methods like Phi29 DNA polymerase-based amplification (multiple displacement amplification) can be used. This isothermal method has high processivity and can be less biased than PCR-based methods for certain applications [10]. Another approach is semirandom primed PCR (SMA), which uses oligonucleotides with random 3' sequences and a universal 5' sequence for uniform amplification, providing relatively uniform coverage of full-length transcripts [10].

Experimental Protocol: Thermal-Bias PCR for Reduced Priming Bias

This protocol, adapted from current research, uses non-degenerate primers and a two-stage temperature process to minimize bias [6].

Principle: A low-temperature annealing step allows the non-degenerate primer to bind to both matched and mismatched template targets. A subsequent high-temperature priming and extension step uses a second primer to selectively and efficiently amplify only the successfully targeted fragments.

Workflow Diagram:

Steps:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a standard PCR mixture containing the mixed-template genomic DNA, two non-degenerate primers, a high-fidelity DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer.

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2 minutes.

- Thermal-Bias Cycling (15-25 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds.

- Low-Temperature Annealing: 45-50°C for 30 seconds. This step allows the targeting primer to hybridize stably to both consensus and non-consensus templates.

- High-Temperature Priming & Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds. At this temperature, a second primer binds specifically to the newly synthesized strand for efficient and controlled amplification.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Library Completion: The resulting amplicon can be purified and processed for sequencing. This method allows for the reproducible production of amplicon sequencing libraries that maintain the proportional representation of rare members in the community [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Mitigating Library Preparation Bias

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Role in Bias Mitigation | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kapa HiFi DNA Polymerase | PCR Amplification | Provides uniform coverage across varying GC content | High-fidelity enzyme optimized for NGS |

| mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit | RNA Extraction | Isolves high-quality RNA, including small RNAs | Provides high-yield and high-quality RNA from various sources [9] |

| UMI Adapters (e.g., Homotrimer Design) | Library Barcoding | Enables accurate counting and correction of PCR duplicates & errors | Random barcode sequence added pre-amplification; trimer design allows error correction [8] |

| SeqPlex Enhanced WTA / WGA Kits | Whole Transcriptome/Genome Amplification | Amplifies low-input/degraded samples with minimal sequence bias | Uses enhanced random primers for comprehensive coverage [16] |

| CircLigase | ssDNA Circligation | Circularizes cDNA for Phi29-based amplification | Allows amplification of short fragments in circularization-based methods [10] |

| Tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC) | PCR Additive | Stabilizes AT-rich templates; reduces mispriming | Improves amplification efficiency of AT-rich regions [9] [12] |

| 5-Bromo-6-chloronicotinic acid | 5-Bromo-6-chloronicotinic acid, CAS:29241-62-1, MF:C6H3BrClNO2, MW:236.45 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Dibromomethyl anastrozole | 5-Dibromomethyl anastrozole, CAS:1027160-12-8, MF:C15H16Br2N2, MW:384.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Quantitative Data on PCR Bias

The following tables summarize key experimental data on how PCR cycle number and enzyme choice impact the accuracy and representation of sequencing results.

Table 1: Impact of PCR Cycle Number on Sequencing Outcomes in Low Biomass Samples

| Sample Type | PCR Cycles | Key Finding | Effect on Richness/Beta-Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Milk [17] | 25, 30, 35, 40 | Increased sequencing coverage with higher cycles | No significant differences detected |

| Murine Pelage [17] | 25 vs 40 | Increased sequencing coverage with higher cycles | No significant differences detected |

| Murine Blood [17] | 25 vs 40 | Increased sequencing coverage with higher cycles | No significant differences detected |

Table 2: Effect of PCR Cycle Number and Protocol on Sequence Artifacts in 16S rRNA Gene Libraries

| Clone Library | No. of PCR Cycles | % Chimeric Sequences | % Unique 16S rRNA Sequences (100% similarity) | Library Coverage (%) (after artifact removal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard [18] | 35 | 13% | 76% | 64% |

| Modified [18] | 15 + 3 reconditioning | 3% | 48% | 89.3% |

Table 3: Polymerase Enzyme Performance Across Genetic Marker Systems of Varying Complexity

| Enzyme | % Correct Reads (Test 1: Simple Locus) | % Correct Reads (Test 2: Single-Copy Nuclear) | % Correct Reads (Test 3: Multi-Gene Family) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phusion [19] | 88-92% | 84% | 65-71% |

| Pwo [19] | 88-92% | - | - |

| KapHF [19] | 88-92% | - | - |

| FastStart [19] | - | - | 65-71% |

| Biotaq [19] | 50-53% | 2% | 17-20% |

Table 4: Impact of PCR Errors on Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) Accuracy

| Sequencing Platform | % CMIs Correctly Called (Before Correction) | % CMIs Correctly Called (After Homotrimer Correction) |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina [8] | 73.36% | 98.45% |

| PacBio [8] | 68.08% | 99.64% |

| ONT (latest chemistry) [8] | 89.95% | 99.03% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Investigating PCR Artifacts in Repetitive DNA Sequences

This protocol is adapted from research investigating the molecular mechanisms of PCR failure and artifact formation when amplifying repetitive DNA, such as TALE binding domains [20].

- Primary Objective: To analyze the formation of deletion artifacts and hybrid repeats during PCR amplification of highly repetitive DNA sequences.

- Sample Preparation:

- Template: Use pure plasmid DNA containing the repetitive sequence of interest (e.g., a TALE assembly in a vector like pTAL2).

- Primers: Design primers that flank the repetitive DNA region.

- PCR Amplification:

- Reaction Setup: Set up standard PCR reactions using a proofreading or non-proofreading DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq).

- Cycling Conditions: Use standard cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 98°C for 3 minutes, followed by 30-35 cycles of denaturation (98°C for 15 seconds), annealing (50-60°C for 30 seconds), and extension (72°C for 30 seconds per kb), with a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes.

- Optimization Attempts: The protocol may include optimization steps such as the addition of DMSO, MgCl2 optimization, and testing different annealing temperatures, which typically fail to resolve artifacts in this specific context [20].

- Analysis:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze PCR products on an agarose gel. Successful amplification of the repetitive region typically results in a "laddering" effect, with multiple bands appearing below and above the expected size, rather than a single clean band.

- Cloning and Sequencing: Isolate individual bands from the gel, clone them into a sequencing vector (e.g., pTOPO), and sequence multiple independent clones.

- Data Interpretation: Sequence analysis reveals that the artifact bands consist of hybrid repeats, where the polymerase has "skipped" over internal repeats, joining distant repeat units together. This is informative for generating models of artifact formation [20].

Protocol: Evaluating PCR Cycle Number for Low Microbial Biomass Samples

This protocol is designed for optimizing 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing from samples with low bacterial biomass and high host DNA content, such as milk, blood, or skin [17].

- Primary Objective: To determine the effect of increased PCR cycle number on sequencing coverage and community representation in low biomass samples.

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect samples (e.g., aseptically collected milk, furred pelage, blood in EDTA tubes) and store at -20°C until processing.

- Extract DNA using a kit designed for complex samples (e.g., PowerFecal DNA Isolation Kit), incorporating a mechanical lysis step (e.g., TissueLyser II) to ensure efficient cell disruption.

- Quantify DNA via fluorometry (e.g., Qubit with dsDNA BR assay).

- Library Preparation with Variable Cycles:

- Target Region: Amplify the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using universal primers (e.g., U515F/806R) flanked by Illumina adapter sequences.

- PCR Reaction: Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Phusion). Reactions should include 100 ng of metagenomic DNA, primers, dNTPs, and polymerase in the manufacturer's recommended buffer.

- Cycling Conditions: Use a touchdown or standard cycling protocol with a variable number of cycles. For matched sample DNA, create separate libraries amplified with different cycle numbers (e.g., 25, 30, 35, and 40 cycles) [17].

- Purification: Pool and purify amplicons using a magnetic bead-based clean-up system (e.g., Axygen Axyprep MagPCR clean-up beads).

- Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence the libraries on an Illumina MiSeq platform.

- Analysis: Compare coverage per sample, detected richness (alpha-diversity), and community structure (beta-diversity) between libraries generated with different cycle numbers.

Workflow: UMI-Based Error Correction for Accurate Molecular Counting

The following diagram illustrates an experimental workflow that uses error-correcting homotrimeric Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to account for PCR errors in sequencing data.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my PCR of repetitive DNA sequences (like TALEs) produce a ladder of bands instead of a single product? A: This laddering effect is a classic symptom of PCR amplification across highly repetitive sequences. The artifacts are caused by the DNA polymerase dissociating and misaligning with a different, homologous repeat unit on the template strand during synthesis. This leads to the generation of hybrid repeats and deletions, which manifest as multiple bands on a gel in increments roughly corresponding to the size of a single repeat unit (e.g., ~100 bp) [20]. Standard optimization (DMSO, Mg2+) often fails, and cloning/sequencing of individual bands is required to confirm the nature of these artifacts.

Q2: For low biomass samples like blood or milk, should I use a high number of PCR cycles to ensure I get enough product for sequencing? A: Yes, but with caution. While increasing PCR cycle number (e.g., to 35 or 40 cycles) is a valid and often necessary strategy to generate sufficient library coverage from low biomass samples, it does increase the risk of accumulating errors and artifacts [17]. The key finding from recent studies is that while higher cycles increase coverage, they may not significantly skew metrics of microbial richness or beta-diversity in these sample types. However, the increased signal must be balanced against the potential for higher noise, and rigorous negative controls are essential to distinguish true signal from contamination or artifacts [17].

Q3: How can I minimize PCR bias and errors in my amplicon sequencing library prep? A: A multi-pronged approach is most effective:

- Enzyme Choice: Select a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) that has been demonstrated to yield a high proportion of correct sequences in complex systems [21] [19].

- Cycle Number: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles required to generate sufficient library yield [18] [21].

- Modified Protocols: For community analysis, consider using a "reconditioning PCR" step (a few cycles with a fresh reaction mixture) to reduce heteroduplex molecules and chimeras [18].

- UMI Integration: For absolute molecular counting, incorporate error-correcting UMIs (e.g., homotrimeric UMIs) before amplification to digitally track and correct for PCR errors and biases in downstream bioinformatics analysis [8].

Q4: My PCR has multiple bands or a smear. What are the primary causes and solutions? A: Nonspecific amplification is a common issue. The main causes and solutions include [22] [21]:

- Annealing Temperature Too Low: Increase the annealing temperature in a step-wise manner or use a gradient cycler to find the optimal temperature.

- Poor Primer Design: Verify primer specificity and avoid self-complementarity or primers with complementary 3' ends.

- Excess Enzyme or Mg2+: Review and optimize the concentration of both the DNA polymerase and Mg2+ in the reaction.

- Template Quality/Quantity: Use high-quality, pure template DNA and ensure the concentration is not too high.

- Hot-Start Polymerase: Use a hot-start polymerase to prevent nonspecific amplification during reaction setup.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Reagents for Managing PCR Bias

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Mitigating PCR Bias |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | Enzymes with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity that significantly reduce nucleotide misincorporation rates, leading to a higher proportion of correct sequences [21] [19]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | Enzymes that are inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup, thereby improving specificity and yield [22] [21]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Random oligonucleotide sequences used to uniquely tag individual RNA/DNA molecules before any amplification steps. This allows bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification biases and digital counting of original molecules [8]. |

| Error-Correcting UMIs (e.g., Homotrimer) | A specific UMI design where the random sequence is synthesized in blocks of three identical nucleotides (trimers). This allows for a "majority vote" correction method, dramatically improving the accuracy of UMI sequences after PCR and sequencing [8]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, GC Enhancers) | Co-solvents that help denature GC-rich templates and resolve secondary structures, promoting more uniform amplification of difficult sequences and improving overall coverage [22] [21]. |

| Pre-Plated, Breakaway PCR Panels | Pre-formulated, ready-to-use reaction panels that reduce manual assay preparation time, minimize pipetting errors and cross-contamination risk, and improve reproducibility across experiments [23]. |

| HCTZ-CH2-HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide Impurity C|402824-96-8 |

| Calcitriol Impurities D | 24-Homo-1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3|CAS 103656-40-2 |

In amplicon sequencing studies, the assumption that final sequencing data accurately represents the original template composition is often violated due to Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) bias. Sequence-intrinsic factors—specifically GC content, secondary structures, and primer-template mismatches—systematically distort amplification efficiency, leading to quantitative inaccuracies that compromise ecological and molecular interpretations [24] [25]. PCR bias manifests when certain DNA templates amplify more efficiently than others due to their inherent sequence properties, creating a distorted representation of the original template mixture in the final sequencing library [25] [5].

The impact of this bias extends beyond technical artifacts to affect biological conclusions. Recent research demonstrates that PCR bias significantly influences widely used ecological metrics, including Shannon diversity and Weighted-Unifrac, while perturbation-invariant measures remain more robust [24]. This review establishes a technical support framework within the broader thesis of mitigating PCR bias in amplicon sequencing, providing researchers with actionable troubleshooting guidelines, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions to recognize, quantify, and minimize these sequence-intrinsic distortions.

Technical FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

How does GC content specifically influence PCR amplification efficiency?

GC-rich templates (typically defined as >60% GC content) present three major challenges during amplification. First, the triple hydrogen bonds in G-C base pairs confer higher thermostability, requiring more energy for denaturation and potentially leading to incomplete strand separation during cycling [26]. Second, these regions readily form stable secondary structures such as hairpins that physically block polymerase progression. Third, GC-rich sequences promote non-specific primer binding and primer-dimer formation [26].

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of GC Content on PCR Amplification

| GC Content Range | Amplification Efficiency Relative to Mid-GC Templates | Primary Challenge | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| <20% GC | Reduced to ~10% of reference level [5] | Low template stability, polymerase slippage | Increase primer specificity, add betaine [5] |

| 40-60% GC (balanced) | Optimal (reference level) [27] | Minimal bias | Standard protocols typically effective |

| 65-80% GC | Severely reduced to ~1% of reference level [5] | Incomplete denaturation, secondary structures | Extended denaturation times, specialized polymerases, additives [26] [5] |

| >80% GC | Nearly eliminated without optimization [5] | Extreme thermostability, complex structures | Combination of polymerase selection, additives, and thermal profile optimization [26] |

The suppression of amplification becomes dramatically more severe at GC contents exceeding 65%, with loci above 80% GC potentially depleted to one-hundredth of their pre-amplification abundance after just 10 PCR cycles when using standard protocols [5]. This bias follows a characteristic profile where mid-GC content templates (approximately 11-56% GC) typically amplify efficiently, creating a "plateau" of reliable amplification, while both extremely low-GC and high-GC fragments are systematically underrepresented [5].

What specific secondary structures most significantly inhibit amplification, and where must they be avoided?

Secondary structures that form in the template DNA, particularly near primer-binding sites, critically impact amplification efficiency by competitively inhibiting primer binding [28]. The most problematic structures include:

- Hairpins with long stems and small loops: When formed inside the amplicon, these structures cause particularly dramatic suppression of amplification efficiency. Research demonstrates that hairpins with 20-bp stems can completely prevent target amplification, yielding no detectable product [28].

- Stable structures near primer-binding sites: Secondary structures forming within approximately 60 bases both inside and outside the amplicon boundary can significantly interfere with primer annealing and extension [28].

Table 2: Effect of Hairpin Structures on qPCR Amplification Efficiency

| Hairpin Location | Stem Length | Loop Size | Amplification Efficiency | Mechanism of Interference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inside amplicon | 10 bp | 5-10 nt | Moderate suppression | Polymerase stalling during elongation |

| Inside amplicon | 20 bp | 5-10 nt | No amplification [28] | Complete blocking of polymerase progression |

| Outside amplicon | 10 bp | 5-10 nt | Mild suppression | Competitive inhibition of primer binding [28] |

| Outside amplicon | 20 bp | 5-10 nt | Severe suppression | Steric hindrance of primer access to template |

| Near primer-binding site (<10 bp) | >8 bp | Any size | Severe suppression | Direct competition with primer annealing [28] |

The magnitude of amplification suppression increases with longer stem lengths and smaller loop sizes. Hairpins formed inside the amplicon cause more dramatic suppression than those outside, with 20-bp stem structures completely eliminating targeted amplification [28]. These effects are primarily attributed to competitive inhibition of primer binding to the template, as confirmed by melting temperature measurements [28].

How do primer-template mismatches impact amplification, and does location matter?

Mismatches between primer and template sequences introduce substantial amplification bias, particularly in complex template systems like microbial community profiling [25]. The impact of a mismatch is highly dependent on its position relative to the primer's 3' end:

- 3' end mismatches (-1 to -3 positions): Most detrimental, often reducing or preventing primer extension entirely due to impaired polymerase initiation [25].

- Middle region mismatches (~-8 position): Moderate impact, potentially reducing annealing efficiency but still permitting some amplification.

- 5' end mismatches (~-14 position): Least detrimental, often tolerated with minimal impact on amplification efficiency [25].

In standard PCR, perfect match primer-template interactions are strongly favored, especially when mismatches occur near the 3' end [25]. However, in complex natural samples with diverse templates, mismatch amplifications can paradoxically dominate when using heavily degenerate primer pools, leading to unexpected distortion of template representation [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Amplification of GC-Rich Templates

GC-rich regions (>60% GC) resist denaturation and form secondary structures that cause polymerases to stall, resulting in blank gels, smeared bands, or low yield [26].

Workflow for Troubleshooting GC-Rich Amplification

Step 1: Polymerase and Buffer Selection

- Choose polymerases specifically optimized for GC-rich templates (e.g., OneTaq DNA Polymerase with GC Buffer or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase) [26].

- Utilize master mixes containing GC enhancers that help disrupt secondary structures.

- For standalone polymerases, add GC enhancer supplements (typically 5-20% of reaction volume).

Step 2: Thermal Profile Optimization

- Extend denaturation time: increase initial denaturation from 30 seconds to 3 minutes and cycle denaturation from 10 seconds to 80 seconds [5].

- Implement a thermal gradient to determine optimal annealing temperature.

- Consider using a "hot start" protocol with higher initial denaturation temperature.

Step 3: Additive Implementation

- Test betaine (1-1.3M final concentration) to reduce secondary structure formation [5].

- Evaluate DMSO (2-10%) to lower melting temperatures and disrupt stable structures [26].

- Avoid overusing additives, as they can inhibit polymerase activity at high concentrations.

Step 4: Magnesium Concentration Titration

- Perform MgClâ‚‚ titration in 0.5 mM increments between 1.0-4.0 mM [26].

- Balance sufficient magnesium for polymerase activity (typically 1.5-2.0 mM) with the need to reduce non-specific binding.

Problem: Secondary Structure Interference

Stable secondary structures in templates competitively inhibit primer binding and block polymerase progression, particularly in regions with inverted repeats or hairpin-forming potential [28] [29].

Protocol: Systematic Evaluation of Secondary Structure Interference

Sequence Analysis Phase

- Scan approximately 60 bases on both sides of primer-binding sites using tools like Mfold or the UNAFold Tool [27].

- Identify potential hairpins with stem lengths >8 bp, particularly those near primer annealing sites.

- Check for homologous regions that might facilitate terminal hairpin formation and self-priming extension [29].

Experimental Verification

- Run PCR products on agarose gel to detect unusual banding patterns or smears indicating structural interference.

- Compare sequencing results from both directions; discrepancies may indicate structure-dependent elongation artifacts [29].

Remediation Strategies

- Redesign primers to avoid structured regions when possible.

- Incorporate additives like betaine or DMSO to destabilize secondary structures.

- Increase annealing temperature to favor specific primer binding over structure formation.

- Use polymerases with high processivity to overcome structural barriers.

Problem: Amplification Bias from Primer-Template Mismatches

In complex template mixtures, primer-template mismatches cause differential amplification efficiencies that distort the representation of original templates in final sequencing libraries [25] [30].

Table 3: Strategies for Minimizing Mismatch-Induced Bias

| Approach | Protocol | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degenerate Primer Pools | Include mixed nucleotides at variable positions in primer sequence [30] | Broad theoretical coverage of sequence variants | Can reduce overall reaction efficiency; may introduce new biases [30] |

| Reduced Cycling | Limit PCR to 20-25 cycles [25] | Minimizes late-cycle stochastic effects | May yield insufficient product for sequencing |

| Specialized PCR Methods | Implement Deconstructed PCR (DePCR) or Thermal-bias PCR [25] [30] | Empirically reduces bias; preserves template ratios | Additional processing steps; requires optimization |

| Touchdown PCR | Start with high annealing temperature, decrease incrementally | Improves specificity in early cycles | Does not address primer depletion issues |

| Polymerase Selection | Use high-fidelity, mismatch-tolerant enzymes | Some tolerance to minor mismatches | Limited effect on severe mismatches, especially at 3' end |

Protocol: Deconstructed PCR (DePCR) for Bias Reduction

DePCR separates linear copying of source templates from exponential amplification, preserving information about original primer-template interactions while reducing bias [25].

Linear Copying Phase

- Set up reaction with DNA template and forward primer only.

- Run 1-2 cycles with extended annealing/extension times.

- This creates complementary strands representing the original template mixture.

Exponential Amplification Phase

- Add reverse primer to the same reaction (or clean product and set up new reaction).

- Perform standard PCR cycling (20-30 cycles).

- The exponential amplification begins from the copied templates rather than the original genomic DNA.

Analysis

- Sequence final products and compare diversity metrics to standard PCR.

- DePCR demonstrates significantly lower distortion relative to standard PCR when mismatches are present [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Addressing Sequence-Intrinsic PCR Bias

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Action | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | OneTaq DNA Polymerase with GC Buffer, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase with GC Enhancer [26] | Improved processivity through structured regions; enhanced fidelity | GC-rich templates; complex secondary structures |

| PCR Additives | Betaine (1-1.3M), DMSO (2-10%), 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine [26] [5] | Reduce secondary structure formation; lower template melting temperature | Hairpin-prone sequences; extremely GC-rich targets |

| Buffer Components | MgClâ‚‚ (1.0-4.0 mM, optimized), specialized GC enhancers [26] | Cofactor for polymerase activity; destabilize G-C bonds | Fine-tuning reaction conditions for specific templates |

| High-Fidelity Master Mixes | Q5 High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix, OneTaq Hot Start 2X Master Mix with GC Buffer [26] | Convenience; optimized formulations for challenging templates | Standardized workflows; screening multiple targets |

| Modified Nucleotides | Phosphorothioate bonds at 3' primer ends [25] | Reduce nucleolytic degradation of primers | Long amplification cycles; complex template mixtures |

Advanced Methodologies

Thermal-Bias PCR Protocol for Complex Templates

Thermal-bias PCR represents a recent advancement that uses temperature manipulation rather than degenerate primers to amplify diverse templates while maintaining their relative abundances [30].

Experimental Workflow:

Primer Design

- Design non-degenerate primers based on consensus sequences.

- Avoid degeneracy while ensuring reasonable coverage of expected variants.

Reaction Setup

- Prepare PCR mix with non-degenerate primers, template DNA, and GC-enhanced polymerase formulation.

- Include appropriate additives based on template characteristics.

Thermal Cycling

- Initial denaturation: 98°C for 3 minutes.

- 5-10 cycles with high annealing temperature (e.g., 68-72°C) to favor specific priming.

- 20-25 cycles with lower annealing temperature (e.g., 55-60°C) to allow limited mismatch tolerance.

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

Validation

- Quantify amplicon yield and distribution.

- Sequence and compare community structure to other methods.

- Thermal-bias PCR allows proportional amplification of targets containing substantial mismatches while using only two non-degenerate primers in a single reaction [30].

Quantitative Assessment of PCR Bias

Protocol: Using qPCR to Measure Amplification Bias Across GC Spectrum

Reference Template Preparation

qPCR Assay Design

- Develop short amplicon assays (50-69 bp) spanning the GC range.

- Ensure amplicons are sufficiently short to avoid internal secondary structure interference.

Amplification and Analysis

- Amplify reference templates under test conditions.

- Quantify abundance of each locus relative to a standard curve of input DNA.

- Normalize quantities relative to mid-GC reference amplicons (48-52% GC).

Bias Calculation

- Plot normalized quantity against GC content for each condition.

- Calculate bias magnitude as the deviation from ideal flat distribution.

- Compare different polymerases, additives, and cycling conditions to identify optimal parameters [5].

Addressing sequence-intrinsic factors in PCR amplification requires a multifaceted approach that begins with recognizing potential sources of bias and implements systematic troubleshooting strategies. The most reliable research outcomes emerge from methodologies that proactively address GC content challenges, secondary structure formation, and primer-template mismatches through appropriate reagent selection, protocol optimization, and validation techniques.

By integrating these troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions into amplicon sequencing workflows, researchers can significantly improve the quantitative accuracy of their studies and draw more reliable biological conclusions. The continued development of methods like Deconstructed PCR and Thermal-bias PCR highlights the importance of maintaining template representation while achieving specific amplification, ultimately supporting the broader thesis of reducing PCR bias in amplicon sequencing research.

Bias-Busting Strategies: Methodological Advances and Practical Applications

In amplicon sequencing studies, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a critical step for amplifying target DNA regions from complex samples. However, standard PCR protocols can introduce significant amplification bias, distorting the true biological representation of different DNA templates in a sample [6] [31]. This bias manifests as the under-representation or complete dropout of specific sequences, such as those with extreme GC content or primer-binding site mismatches, ultimately compromising the accuracy of downstream sequencing data [31]. This guide details wet-lab optimization strategies—focusing on polymerase selection, chemical additives, and thermocycling protocols—to minimize these biases and generate more representative amplicon libraries for your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on PCR Bias

1. What is the biggest source of bias during library preparation for amplicon sequencing? Research has identified that the PCR amplification step itself during library preparation is the most discriminatory stage. One study traced genomic sequences with GC content ranging from 6% to 90% and found that as few as ten PCR cycles could deplete loci with a GC content >65% to about 1/100th of the mid-GC reference loci. Amplicons with very low GC content (<12%) were also significantly diminished [31].

2. Can using degenerate primers reduce bias? While degenerate primers (pools containing mixed nucleotide sequences) are often used to amplify targets with variations in their primer-binding sites, they can inadvertently reduce overall PCR efficiency and distort representation. Non-degenerate primers can sometimes produce better results, and novel methods like "thermal-bias" PCR are being developed to amplify mismatched targets without degenerate primers, leading to libraries that better maintain the proportional representation of rare sequences [6].

3. My thermocycler's manual mentions "ramp rate." Does this really affect my results? Yes, the temperature ramp rate of your thermocycler can be a critical hidden factor. Studies show that slower default ramp speeds can significantly improve the amplification of GC-rich templates. Simply switching from a fast-ramping to a slow-ramping instrument extended the GC-content plateau from 56% to 84% before seeing a drop in amplification efficiency [31]. This highlights the need to optimize and document your thermocycling equipment and protocols.

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Common PCR Challenges

Use the following tables to diagnose and resolve common issues that contribute to PCR bias and amplification failure.

Table 1: Troubleshooting No or Low Amplification Product

| Possible Cause | Recommended Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|

| Incorrect Annealing Temperature | Recalculate primer Tm and test a gradient, starting 3–5°C below the lowest Tm [32] [33]. |

| Poor Primer Design | Verify specificity, avoid self-complementarity, and ensure primers have a GC content of 40–60% and a Tm within 5°C of each other [34] [33]. |

| Complex Template (e.g., High GC) | Use a polymerase designed for GC-rich targets. Add enhancers like 1–10% DMSO or 0.5 M–2.5 M betaine [22] [34] [35]. |

| Suboptimal Denaturation | Increase denaturation time and/or temperature. For GC-rich templates, extend the denaturation time during cycling [32] [31]. |

| PCR Inhibitors Present | Re-purify the template DNA or dilute the sample to reduce inhibitor concentration [22] [35]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Non-Specific Products and Smearing

| Possible Cause | Recommended Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|

| Low Annealing Temperature | Increase the annealing temperature in increments of 2°C to improve specificity [33] [35]. |

| Excessive Cycle Number | Reduce the number of PCR cycles (typically to 25–35), as overcycling increases non-specific product accumulation [32] [35]. |

| Too Much Template or Enzyme | Reduce the amount of input template or DNA polymerase as per manufacturer guidelines [22] [35]. |

| Primer Dimer Formation | Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent activity at room temperature and set up reactions on ice [22] [35]. |

| Long Annealing Time | Shorten the annealing time (e.g., to 5–15 seconds) to minimize primer binding to non-specific sequences [35]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Thermal-Bias PCR for Reducing Primer-Bias

This protocol uses two non-degenerate primers with a large difference in annealing temperatures to stably amplify targets containing mismatches in their primer-binding sites, avoiding the inefficiencies of degenerate primers [6].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- DNA Template: 1–1000 ng of mixed-genome sample.

- Primers: Two non-degenerate primers designed for the target region, with a calculated Tm difference of >10°C.

- High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: e.g., Q5 or Phusion.

- Appropriate 10X Reaction Buffer.

Method:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, DNA polymerase, and the low-Tm primer only. Add the DNA template.

- Initial Amplification Stage (5–10 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds.

- Annealing: Use a temperature 3°C below the Tm of the low-Tm primer. This allows it to bind to both consensus and non-consensus targets.

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds/kb.

- Second Amplification Stage: Add the high-Tm primer to the reaction tube.

- Main Amplification Stage (20–25 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: Use a single temperature suitable for the high-Tm primer (e.g., 72°C). The low-Tm primer will no longer bind, and only the correctly extended products from the first stage are amplified.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

Protocol 2: Mitigating GC-Bias in Amplicon Libraries

This protocol optimizes denaturation and incorporates betaine to evenly amplify sequences across a wide GC spectrum [31].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- DNA Template: Composite sample with a range of GC contents.

- DNA Polymerase: A robust, high-fidelity enzyme such as Phusion or AccuPrime Taq HiFi.

- 5M Betaine Solution: Sterile-filtered.

Method:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a standard master mix and add betaine to a final concentration of 0.5–2 M.

- Initial Denaturation: Perform at 98°C for 3 minutes (a significant increase from the typical 30 seconds) to ensure complete separation of GC-rich duplexes.

- Amplification Cycles (25–35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 60–80 seconds per cycle (extended from the typical 10–30 seconds).

- Annealing: Temperature optimized for your primer set.

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds/kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 minutes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR Bias Minimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Bias Reduction | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Reduces misincorporation errors due to proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity, leading to more accurate amplification [33]. | Cloning and sequencing applications where sequence accuracy is critical [33]. |

| Polymerase Blends (e.g., AccuPrime Taq HiFi) | Combines polymerases for improved efficiency and uniformity when amplifying complex mixed templates or difficult GC-rich targets [31]. | Generating even coverage across genomic loci with diverse base compositions [31]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation at lower temperatures [22]. | Improving specificity and yield in reactions prone to mispriming or when using complex templates [22] [35]. |

| Betaine | A chemical additive that equalizes the melting temperature of DNA, improving the amplification efficiency of GC-rich templates [31] [34]. | Added at 0.5–2 M to rescue amplification of high-GC targets that fail with standard protocols [31]. |

| DMSO | Disrupts secondary structures and reduces DNA melting temperature, helping to amplify templates with strong secondary structures or high GC content [32] [34]. | Used at 1–10% to assist in denaturing complex templates [34]. |

| Bupropion morpholinol | Bupropion morpholinol, CAS:357399-43-0, MF:C13H18ClNO2, MW:255.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| R 29676 | R 29676, CAS:53786-28-0, MF:C12H14ClN3O, MW:251.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In amplicon sequencing studies, PCR bias is a significant challenge that can distort sequence representation and compromise the accuracy of quantitative results. Traditional methods often rely on degenerate primer pools—mixtures of primers with varying bases at specific positions—to target diverse sequences. However, this approach can introduce amplification biases, favoring certain templates over others. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address specific issues related to PCR bias and adopt advanced primer design strategies for more reliable and accurate amplicon sequencing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main sources of PCR bias in amplicon sequencing? PCR bias in amplicon sequencing arises from several sources. The major forces skewing sequence representation are PCR stochasticity (the random sampling of molecules during early amplification cycles) and polymerase errors, which become very common in later PCR cycles but typically remain at low copy numbers [3]. Other significant factors include:

- GC Bias: Sequences with very high or very low GC content can amplify less efficiently. This has been identified as a principal source of bias during the library amplification step [31].

- Template Switching: A process where chimeric sequences are formed during amplification, though this is typically rare and confined to low copy numbers [3].

- Primer Mismatches: Variation in primer binding sites, especially when using universal or degenerate primers, leads to differential amplification efficiency [13].

2. How do degenerate primers contribute to amplification bias? While degenerate primers (pools of primers with nucleotide variations) are designed to broaden the range of amplifiable templates, they introduce several issues. They often ignore primer specificity, which can lead to false positives in applications like viral subtyping [36]. The different primers within a degenerate pool have varying melting temperatures (Tm) and binding efficiencies, which can cause uneven amplification of target sequences [13]. Furthermore, calculating the thermodynamic properties of a degenerate pool is complex, and heuristic methods based on mismatch counts can be misleading for predicting actual hybridization efficiency [36].

3. What are the key advantages of non-degenerate, targeted primer design? Targeted, non-degenerate approaches offer greater specificity and predictability. They allow for the design of primers with optimized and uniform thermodynamic properties, such as melting temperature, which leads to more balanced amplification [37]. These methods minimize off-target amplification and the formation of chimeras by ensuring primers are specific to their intended target [38]. By moving the design process away from consensus sequences and towards evaluating individual primers against diverse templates, these approaches better account for sequence variation and avoid biases introduced by degenerate bases [37].

4. Which modern tools can help design targeted, non-degenerate primers? Several advanced bioinformatics tools have been developed to address the limitations of degenerate primers:

- PMPrimer: A Python-based tool that automatically designs multiplex PCR primer pairs using a statistical filter to identify conserved regions based on Shannon's entropy, tolerates gaps, and evaluates primers based on template coverage and taxon specificity [37].

- varVAMP: A command-line tool for designing degenerate primers for viral genomes. It addresses the "maximum coverage degenerate primer design" problem by finding a trade-off between specificity and sensitivity, using a penalty system that incorporates primer parameters, 3’ mismatches, and degeneracy [38].

- Thermodynamic-Based Methods: New methods propose moving beyond simple mismatch counting. They use suffix arrays and local alignment to identify candidate regions, followed by rigorous thermodynamic analysis to evaluate the hybridization efficiency of primers against all potential targets, ensuring high specificity and sensitivity [36].

5. How can I minimize GC bias in my amplicon sequencing library preparation? GC bias can be significantly reduced by optimizing the PCR conditions during library preparation. Key steps include [31]:

- Using Betaine: Adding 2M betaine to the PCR reaction can help rescue amplification of extremely GC-rich fragments.

- Extending Denaturation Times: Simply extending the initial denaturation step and the denaturation step during each cycle can overcome the detrimental effects of fast temperature ramp rates on thermocyclers, improving the amplification of GC-rich templates.

- Optimizing Polymerase Blends: Substituting polymerases with specialized blends (e.g., AccuPrime Taq HiFi) can also contribute to more uniform amplification across a wide GC spectrum.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Taxonomic Abundance Estimates from Metabarcoding Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Primer-induced bias from variable binding sites.

- Solution: Shift to markers with more conserved priming sites or use tools like PMPrimer to design primers in regions with high sequence conservation, as determined by low Shannon's entropy [37] [13]. For highly diverse targets, consider a varVAMP-like approach that designs multiple discrete, non-degenerate primer sets to cover different variants, minimizing the need for high degeneracy [38].

- Cause: Amplification bias from PCR cycle number.

- Solution: Reduce the number of PCR cycles in the initial, locus-specific amplification round. Surprisingly, simply reducing cycles may not be sufficient on its own [13]. Combine cycle reduction with increased template concentration (e.g., 60 ng in a 10 µl reaction) to maximize the starting molecule number and reduce stochastic effects [13].

- Cause: Locus copy number variation (CNV).

- Solution: Be aware that CNV of the target locus between taxa will affect abundance estimates in both amplicon-based and PCR-free methods [13]. If a correlation between input DNA and read count can be established, apply taxon-specific correction factors to the read counts to improve abundance estimates [13].

Problem: Poor Amplification of Targets with Extreme GC Content

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete denaturation of high-GC templates due to fast thermocycling.

- Solution: Optimize the thermocycling profile. Extend the denaturation time during each cycle (e.g., from 10 s to 80 s) and use a thermocycler with a slower ramp speed to ensure complete denaturation of GC-rich templates [31].

- Cause: Non-optimal polymerase or reaction chemistry.

- Solution: Use a PCR additive like 2M betaine. Furthermore, test alternative polymerase formulations, such as the AccuPrime Taq HiFi blend, which may perform better across a wide range of GC contents [31].

Problem: Designing Pan-Specific Primers for Highly Variable Viral Genomes

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: High genomic variability makes finding conserved regions difficult.

- Solution: Use a tool like varVAMP that is specifically designed for variable viral genomes. It uses a k-mer-based approach on consensus sequences derived from a multiple sequence alignment and employs Dijkstra's algorithm to find an optimal tiling path of amplicons with minimal primer penalties [38].

- Cause: Traditional degenerate primers lead to false positives or poor sensitivity.

- Solution: Employ a thermodynamics-driven design method. These methods use local alignment to find candidate primer binding sites across whole genomes and then perform a rigorous thermodynamic analysis to evaluate the true binding affinity, ensuring specificity and sensitivity beyond simple mismatch counting [36].

Experimental Protocols & Data

This protocol is designed to reduce the under-representation of sequences with extreme GC content during the library amplification step.

Reaction Setup:

- Use 15 ng of adapter-ligated DNA library.

- Set up a 10 µl PCR reaction using the AccuPrime Pfx SuperMix or a similar robust polymerase blend.

- Add forward and reverse primers to a final concentration of 0.5 µM each.

- Critical Addition: Include a final concentration of 2M betaine.

Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 3 minutes at 95°C.

- Cycling (10-18 cycles):

- Denaturation: 80 seconds at 95°C. Note: This extended denaturation time is crucial for GC-rich templates.

- Annealing: 30 seconds at 58°C.

- Extension: 30 seconds at 68°C.

- Final Extension: 5 minutes at 68°C.

Clean-up: Purify the PCR product using Agencourt RNAClean XP beads or a similar solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) method before quantification and sequencing.

Table 1: Relative Impact of Different PCR-Induced Distortions on Sequence Representation [3]

| Source of Error | Relative Impact | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Stochasticity | Major | The primary force skewing sequence representation in low-input libraries; most significant for single-cell sequencing. |

| Polymerase Errors | Common but low impact | Very frequent in later PCR cycles, but erroneous sequences are confined to small copy numbers. |

| Template Switching | Minor | A rare event, typically confined to low copy numbers. |

| GC Bias | Variable | A significant source of bias during library PCR; effect can be minimized with protocol optimization [31]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Mitigating PCR Bias in Amplicon Sequencing

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Betaine | PCR additive that equalizes the amplification efficiency of templates with different GC contents by reducing the melting temperature disparity [31]. | Used at a final concentration of 2M. |

| AccuPrime Taq HiFi | A specialized blend of DNA polymerases noted for its performance in amplifying sequences with a broad range of GC content [31]. | An alternative to Phusion HF for GC-balanced amplification. |

| PMPrimer | Bioinformatics tool for automated design of multiplex PCR primers; uses Shannon's entropy to find conserved regions and evaluates template coverage [37]. | Python-based; useful for designing targeted primers for diverse templates like 16S rRNA or specific gene families. |

| varVAMP | Command-line tool for designing degenerate primers for tiled whole-genome sequencing of highly variable viruses; addresses the MC-DGD problem [38]. | Optimized for viral pathogen surveillance (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, HEV). |

Workflow Visualization

Primer Design Strategy Evolution

GC Bias Mitigation Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are UMIs, and why are they crucial for amplicon sequencing? Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short, random oligonucleotide sequences (typically 8-12 nucleotides long) that are ligated to individual DNA or RNA molecules before any PCR amplification steps [39] [40]. In amplicon sequencing, they are crucial for accurate molecular counting. After sequencing, reads sharing the same UMI are collapsed into a single read, which removes PCR duplicates and corrects for amplification biases, thereby improving the accuracy of quantitative applications like gene expression analysis or variant calling [8] [40] [41].

2. What are the primary sources of UMI errors? UMI errors originate from three major sources [39]:

- PCR Amplification Errors: Random nucleotide substitutions accumulate over multiple PCR cycles. With each cycle using previously synthesized products as templates, these errors can propagate, causing erroneous UMIs to be counted as distinct molecules [8] [39].

- Sequencing Errors: Incorrect base calls during sequencing lead to mismatches, insertions, or deletions in the UMI sequence. The error profile varies by platform: Illumina has low rates but mainly substitution errors, while long-read platforms like PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) are more susceptible to indels [39] [42].

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis Errors: These occur during the chemical manufacturing of the UMIs themselves, primarily involving truncations or unintended extensions due to the finite coupling efficiency of each synthesis step [39].

3. My UMI deduplication tool is running slowly and using a lot of memory. What could be the cause? Several factors can impact the performance of tools like UMI-tools [43]:

- Run Time: Shorter UMIs, higher sequencing error rates, and greater sequencing depth can all increase the "connectivity" between UMI sequences, leading to larger networks for the algorithm to resolve and longer processing times.

- Memory Usage: Processing chimeric read pairs or unmapped reads in paired-end sequencing modes can require keeping large buffers of data in memory, significantly increasing memory requirements.

4. How do homotrimeric UMIs correct errors, and when should I use them? Homotrimeric UMIs are an advanced design where each nucleotide in a conventional UMI is replaced by a triplet of identical bases (e.g., 'A' becomes 'AAA') [8] [39]. This creates internal redundancy. During analysis, a "majority vote" is applied to each triplet to correct single-base errors. For example, a sequenced 'ATA' triplet can be corrected to 'AAA' [8]. This design is particularly beneficial in scenarios prone to high error rates, such as single-cell RNA-seq with high PCR cycle numbers or long-read sequencing, as it significantly improves the accuracy of molecular counting [8].

5. What computational tools are available for UMI error correction, and how do I choose? The choice of tool depends on your UMI design and sequencing platform. The table below summarizes key tools:

Table 1: Comparison of UMI Deduplication Tools

| Tool Name | Key Features | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UMI-tools [43] [39] | Graph-based network, Hamming distance (substitutions) | Short-read data with monomeric UMIs and moderate error rates | Struggles with indel errors; can be slow with large datasets; single-threaded |

| UMI-nea [42] | Levenshtein distance (substitutions & indels), multithreading, adaptive filtering | Error-prone data (e.g., long-reads), ultra-deep sequencing, and structured UMIs | |

| Homotrimer Correction [8] | Majority voting and set cover optimization, built-in redundancy | Data generated with homotrimeric UMI designs, high PCR cycle conditions | Requires specific experimental design using homotrimer UMIs |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inflated Molecular Counts After UMI Deduplication

Potential Causes and Solutions:

High PCR Cycle Number:

- Cause: Excessive PCR cycles introduce and propagate errors within UMI sequences, causing a single original molecule to appear as multiple distinct molecules [8].

- Solution: Optimize your library preparation protocol to use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary. Consider adopting error-resilient UMI designs like homotrimeric UMIs, which have been shown to maintain over 96% accuracy even at high PCR cycles (35 cycles), whereas monomeric UMI accuracy drops significantly [8].

Using an Inappropriate Computational Tool:

- Cause: Tools that only use Hamming distance (like UMI-tools) cannot correct for insertion and deletion (indel) errors, which are common in long-read sequencing [42].

- Solution: If you are using long-read sequencing or a UMI design prone to indels, switch to a tool that uses Levenshtein distance, such as UMI-nea, which can handle both substitutions and indels [42].

Issue: Poor Amplification of GC-Rich or GC-Poor Targets

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: This is a form of PCR amplification bias, where the standard PCR conditions and enzyme formulations do not efficiently denature or amplify templates with extreme GC content [5].

- Solutions:

- Optimize PCR Conditions: A study found that simply extending the denaturation time during thermocycling can significantly improve the representation of high-GC loci. Adding betaine (2M) and using polymerase blends like AccuPrime Taq HiFi can further create a more balanced amplification across a wide GC spectrum (e.g., 23% to 90% GC) [5].

- Avoid Degenerate Primers: While often used to capture diverse templates, degenerate primers can themselves be a source of bias and inhibit efficient amplification. Consider a "thermal-bias" PCR protocol that uses non-degenerate primers with a large difference in annealing temperatures to isolate targeting and amplification stages [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating UMI Error Correction Using a Common Molecular Identifier (CMI)

This protocol, adapted from a recent study, provides a robust method to quantify the accuracy of your UMI correction strategy [8].