FISH for Microbial Detection: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH) for the detection, identification, and localization of microorganisms.

FISH for Microbial Detection: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH) for the detection, identification, and localization of microorganisms. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles and evolution of FISH technology, detailed methodological protocols for diverse applications, practical troubleshooting strategies for common challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks alongside comparative analysis with other diagnostic techniques. By synthesizing current research and practical insights, this guide serves as an essential resource for implementing and optimizing FISH in both research and clinical microbiology settings, highlighting its unique advantages in culture-free, in-situ analysis of complex microbial communities.

The Foundation of FISH: Principles, Probes, and Technological Evolution in Microbiology

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) represents a cornerstone molecular cytogenetic technique that enables the direct visualization and localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within morphologically preserved chromosomes, cells, or tissue sections [1]. The fundamental principle underpinning FISH involves the hybridization of fluorescently labeled DNA or RNA probes to complementary target sequences, allowing researchers to detect the presence, absence, and spatial organization of genetic elements within a biological context [2]. Since its development in the early 1980s, FISH has evolved into an indispensable tool for genetic counseling, medicine, species identification, and increasingly, microbial detection research [1].

For investigators studying microbial communities, FISH offers a powerful approach to identify, quantify, and spatially localize microorganisms within complex samples without the need for cultivation. This application note details the core principles of probe hybridization, provides detailed protocols adaptable for microbial detection, and presents key reagent solutions to facilitate effective research planning and implementation.

Core Principles of FISH

The Hybridization Process

The essence of FISH technology centers on the precise molecular recognition between a labeled nucleic acid probe and its complementary target sequence within a cellular environment. This process relies on the fundamental principle of base pairing (A-T and G-C for DNA; A-U and G-C for RNA) under specific hybridization conditions [1] [2]. The technique preserves the structural integrity of the sample while providing critical information about genetic architecture that would be lost with nucleic acid extraction methods.

Probes are typically designed as single-stranded DNA or RNA fragments complementary to a nucleotide sequence of interest [1]. For microbial detection, these are often targeted to species-specific 16S rRNA sequences due to their phylogenetic significance and high copy number within bacterial cells. When the probe encounters its complementary target under appropriate conditions, it forms a stable double-stranded hybrid through hydrogen bonding, which can then be visualized via fluorescence microscopy due to the attached fluorophore.

Probe Design and Labeling Strategies

FISH probes can be categorized based on their target scope and composition:

- Locus-specific probes hybridize to particular genomic regions and are essential for detecting specific microbial taxa or functional genes [1].

- Whole-chromosome painting probes consist of mixtures that bind along entire chromosomes, less commonly used in microbial research [1].

- Oligonucleotide probes (typically 20-50 nucleotides) offer high specificity and are widely employed for microbial rRNA targeting [1].

Probe labeling can be achieved through various methods, including nick translation, PCR with tagged nucleotides, or in vitro transcription for RNA probes [1] [3]. Modern FISH Tag kits utilize enzymatic incorporation of amine-modified nucleotides followed by chemical labeling with amine-reactive dyes, resulting in higher incorporation efficiency and improved signal-to-noise ratios [3].

Table 1: Common Fluorophores Used in FISH Applications

| Fluorophore | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI | 358 | 461 | Nuclear counterstain |

| FITC | 495 | 519 | Standard labeling (green) |

| Alexa Fluor 555 | 555 | 565 | Standard labeling (red) |

| Texas Red | 589 | 615 | Standard labeling (far red) |

| Alexa Fluor 647 | 650 | 668 | Standard labeling (near IR) |

| Cy3 | 554 | 568 | Standard labeling (orange) |

Detailed FISH Protocol for Microbial Detection

This protocol adapts established FISH methodologies for the detection and visualization of microorganisms in sample specimens, incorporating critical steps for optimal hybridization and signal detection [1] [2] [3].

Sample Preparation and Fixation

- Sample Collection: Collect microbial cells from appropriate sources (culture, environmental samples, biofilms). For planktonic cells, concentrate via centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Fixation: Resuspend cell pellet in fresh fixative solution (4% formaldehyde or paraformaldehyde in PBS) and incubate for 1-4 hours at 4°C. This step preserves cellular morphology and prevents degradation.

- Permeabilization: Pellet cells (5,000 × g, 5 min), wash with PBS, and treat with permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100 or Tween-20 in PBS) for 10-15 minutes. This creates pores for probe penetration.

- Slide Preparation: Apply fixed cell suspension onto clean microscope slides and air dry. Dehydrate through an ethanol series (50%, 80%, 96%; 3 min each) and air dry completely.

Hybridization Procedure

- Probe Preparation: Dilute the fluorescently labeled probe in appropriate hybridization buffer to working concentration (typically 2-10 ng/μL). Specific probe sequences should target microbial 16S rRNA or other signature genes.

- Denaturation: Apply probe solution to sample area, add coverslip, and seal edges with rubber cement. Denature slide and target DNA simultaneously on a preheated hotplate or hybridizer at 75°C for 2-5 minutes [2].

- Hybridization: Immediately transfer slides to a humidified chamber and incubate at appropriate hybridization temperature (typically 37-46°C, depending on probe design) for 2-16 hours (often overnight) to allow specific probe binding [2].

Post-Hybridization Washing and Detection

- Stringency Washes: Remove coverslips carefully and wash slides in pre-warmed wash buffer (0.4× SSC at 72°C for 2 minutes) to remove nonspecifically bound probes [2].

- Secondary Wash: Perform additional wash in room temperature solution (2× SSC with 0.05% Tween-20 for 30 seconds) [2].

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Apply appropriate counterstain (e.g., DAPI for DNA) in antifade mounting medium and add coverslip. For signal amplification, proceed with tyramide signal amplification (TSA) using SuperBoost kits before counterstaining [3].

Microscopy and Analysis

Visualize samples using epifluorescence or confocal microscopy equipped with appropriate filter sets for the fluorophores used. For microbial quantification, count specific signals in multiple random fields until at least 100-200 cells are enumerated. Analyze spatial distribution patterns when examining complex samples like biofilms.

Advanced FISH Methodologies

Single-Molecule RNA FISH (smFISH)

For detecting and quantifying individual mRNA molecules in microbial cells, smFISH (also known as Stellaris RNA FISH) employs multiple short singly labeled oligonucleotide probes (typically up to 48) binding to a single transcript [1]. This approach provides sufficient localized fluorescence to detect and localize each target mRNA molecule with high precision, enabling studies of gene expression heterogeneity in microbial populations at single-cell resolution.

Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)

For detecting low-abundance targets or enhancing weak signals in microbial detection, TSA systems (such as SuperBoost kits) offer sensitivity 10-200 times greater than standard FISH methods [3]. This enzyme-mediated methodology deposits multiple fluorophore-labeled tyramide molecules at the probe binding site, dramatically amplifying signal intensity for challenging targets like low-copy-number genes or small microorganisms.

Table 2: Signal Amplification Kits for Low-Abundance Targets

| Kit Type | Sensitivity Gain | Key Components | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard TSA | 10-50x | HRP-streptavidin, Tyramide-dye | Routine signal enhancement |

| SuperBoost Kits | 10-200x | Poly-HRP, Alexa Fluor tyramides | Very rare or low-abundance targets |

| FISH Tag Kits | N/A | Amine-modified nucleotides, Succinimidyl ester dyes | High signal-to-noise multiplexing |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful FISH experimentation requires specific reagents and systems optimized for particular sample types and detection requirements. The following table outlines essential solutions for implementing FISH in microbial detection research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FISH Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation Solutions | 4% Formaldehyde, Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS | Preserves cellular morphology and prevents nucleic acid degradation |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100 (0.1%), Tween-20, Proteinase K | Creates membrane pores for probe entry; concentration optimization critical |

| Hybridization Buffers | SSC-based buffers with formamide, dextran sulfate | Maintains pH and ionic strength during hybridization; formamide reduces melting temperature |

| Labeling Systems | FISH Tag DNA/RNA Kits, Nick translation kits | Enzymatic incorporation of fluorophores or haptens into nucleic acid probes |

| Signal Amplification | SuperBoost Tyramide Kits, TSA Plus Systems | Dramatically enhances detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets |

| Detection Fluorophores | Alexa Fluor dyes (488, 555, 594, 647) | Photostable fluorophores with high quantum yields for multiplex detection |

| Counterstains | DAPI, Hoechst 33258, Propidium Iodide | Provides structural context by staining nucleic acids |

| Mounting Media | Antifade reagents (Vectashield, ProLong) | Preserves fluorescence during microscopy and storage |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Successful FISH implementation requires careful attention to potential technical challenges:

- High Background Fluorescence: Increase stringency of post-hybridization washes by raising temperature or decreasing salt concentration; reduce probe concentration; ensure complete removal of unbound probe [1] [2].

- Weak or Absent Signal: Extend hybridization time; increase probe concentration; incorporate signal amplification; verify probe design and labeling efficiency; check fluorophore integrity [3].

- Autofluorescence in Samples: Employ ethanol washes to reduce autofluorescence; utilize fluorophores with emission spectra distinct from sample autofluorescence; consider chemical treatments to reduce autofluorescence [1].

- Poor Cellular Morphology: Optimize fixation conditions (type, concentration, duration); avoid over-digestion during permeabilization steps [4].

For quantitative analysis, ensure consistent hybridization conditions across experiments and include appropriate positive and negative controls. Newer computational approaches for image analysis can further enhance the objectivity and reproducibility of FISH-based microbial detection and quantification.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) represents one of the most significant technological evolutions in molecular cytogenetics, enabling researchers to visualize and map genetic material within intact cells and tissues. This revolutionary technique has transformed our understanding of genomic organization, gene expression, and chromosomal abnormalities across diverse fields including microbiology, oncology, and genetic disease research. The journey from radioactive detection methods to modern fluorescent approaches marks a critical advancement in diagnostic precision, safety, and multiplexing capability. Within microbial detection research specifically, FISH has emerged as an indispensable tool for identifying and characterizing microorganisms in their native environments without the need for cultivation [5]. The development of FISH probes has progressed from simple single-color DNA detection to sophisticated multiplex assays capable of simultaneously visualizing multiple genetic targets, with the global FISH probe market reflecting this technological expansion through substantial growth from USD 1.14 billion in 2025 to a projected USD 2.27 billion by 2034 [6]. This application note details the historical development, current methodologies, and practical implementation of FISH technologies, with particular emphasis on applications within microbial detection research.

Technological Evolution: From Radioactive to Fluorescent Detection

The development of in situ hybridization technologies has traversed a remarkable path from radioactive isotopes to sophisticated fluorescent detection systems. The earliest ISH methodologies utilized radioactive labels such as tritium (³H) or phosphorus (³²P), which provided the sensitivity required for initial detection of specific DNA and RNA sequences but posed significant limitations including safety hazards, long exposure times (often requiring weeks to months), and poor spatial resolution. The transition to non-radioactive detection methods began in the 1980s with the introduction of hapten-labeled probes detected through enzymatic reactions, but the true revolution arrived with the implementation of fluorescent labeling.

The advent of FISH technology addressed multiple limitations simultaneously by incorporating fluorophore-conjugated nucleotides directly into nucleic acid probes. This innovation provided researchers with a safer, faster, and more versatile detection platform that preserved cellular morphology while allowing direct visualization through fluorescence microscopy. The initial single-color FISH protocols quickly evolved into dual-color systems, enabling the simultaneous detection of two genetic targets. Contemporary FISH technologies now support multiplex assays with capacity for dozens of simultaneous detections through sophisticated probe design and spectral imaging [7].

The technological progression of FISH has been characterized by several key developments:

- Probe Design Evolution: Advancements shifted from large genomic clones (cosmids, BACs) to shorter oligonucleotides (OligoPaint), improving resolution and specificity [8]

- Signal Amplification Systems: Development of tyramide signal amplification (TSA) and hybridization chain reaction (HCR) dramatically increased detection sensitivity [8]

- Multiplexing Capabilities: Introduction of spectral karyotyping (SKY) and multiplex FISH (M-FISH) enabled complete chromosome visualization [7]

- Automation and AI Integration: Recent developments include automated imaging platforms and AI-assisted analysis tools like U-FISH, which provides universal spot detection across diverse FISH datasets [9]

Table 1: Evolution of Key FISH Probe Types and Their Applications

| Probe Type | Historical Period | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radioactive ISH Probes | 1969-1980s | Used ³H or ³²P isotopes; long exposure times; safety concerns | Initial gene mapping; viral detection |

| First-Generation FISH | 1980s-1990s | Single fluorophore labels; limited multiplexing | Chromosome enumeration; gene localization |

| DNA Probes | 1990s-Present | Stable hybridization; 45% market share in 2024 [6] | Oncology diagnostics; genetic disease detection |

| RNA Probes | 2000s-Present | Detection of gene expression; fastest growing segment [6] | Microbial identification; transcriptomics |

| Multiplex FISH | 2010s-Present | Simultaneous detection of multiple targets | Complex chromosomal rearrangements |

| Live-FISH | 2020s-Present | Maintenance of cell viability during hybridization | Targeted cultivation of soil microbiomes [5] |

Current Market Landscape and Quantitative Analysis

The FISH probe market demonstrates robust growth driven by increasing applications in clinical diagnostics and research. Current market analysis reveals a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.93% from 2025 to 2034, with the market value projected to reach approximately USD 2.27 billion by 2034 [6]. This expansion reflects the growing integration of FISH technologies into routine clinical practice, particularly in oncology and genetic disorder diagnostics.

The market distribution by probe type shows DNA probes maintaining dominance with 45% market share in 2024, while RNA probes represent the fastest-growing segment due to increasing applications in gene expression analysis and spatial transcriptomics [6]. From a technological perspective, recent developments have included the incorporation of quantum dots as fluorescent labels, which offer superior photostability and narrow emission spectra ideal for multiplex applications [6]. The label type segmentation shows fluorescent dyes currently leading the market with 50% share, while quantum dots are anticipated to expand at a significant CAGR from 2025 to 2034 [6].

Application analysis reveals oncology as the dominant segment with 55% market share in 2024, largely driven by the critical role of FISH in detecting oncogenic mutations, chromosomal translocations, and gene amplifications essential for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy selection [6]. The prenatal and genetic disorder diagnosis segment is expected to grow at the fastest rate during the forecast period, reflecting increasing implementation of FISH in non-invasive prenatal testing and neonatal screening [6].

Geographically, North America dominated the FISH probe market with approximately 47% share in 2024, while the Asia Pacific region is expected to register the fastest growth rate due to rising prevalence of target diseases, improving healthcare facilities, and growing demand for in vitro diagnostic testing [6] [10]. This regional distribution corresponds with healthcare infrastructure development and research funding patterns.

Table 2: Global FISH Probe Market Segmentation and Growth Projections

| Segmentation Category | 2024 Market Share | Projected CAGR (2025-2034) | Key Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Probe Type | |||

| DNA Probes | 45% [6] | Stable growth | Cancer diagnostics; genetic disorder detection |

| RNA Probes | Smaller share | Fastest growing [6] | Gene expression analysis; spatial transcriptomics |

| By Application | |||

| Oncology | 55% [6] | 7.93% overall market CAGR [6] | Precision medicine; targeted therapies |

| Prenatal & Genetic Disorders | Smaller share | Fastest growing segment [6] | Non-invasive prenatal testing; newborn screening |

| By End User | |||

| Hospitals & Diagnostic Centers | 50% [6] | Steady growth | Routine clinical diagnostics |

| Research & Academic Institutes | Smaller share | Fastest growing [6] | Spatial-omics; basic research |

| By Region | |||

| North America | 47% [6] | Stable growth | Advanced healthcare infrastructure |

| Asia Pacific | Smaller share | Fastest growing [6] | Improving healthcare facilities |

Application in Microbial Detection Research

FISH technologies have revolutionized microbial detection research by enabling the identification, quantification, and spatial localization of microorganisms within complex environmental samples without requiring cultivation. The application of FISH in microbiology has been particularly valuable for studying uncultivable microorganisms, which represent the majority of microbial diversity in most environments. The technique has been successfully applied to diverse fields including environmental microbiology, human microbiome research, and industrial process monitoring.

Recent advances in Live-FISH have further expanded applications by maintaining cell viability throughout the hybridization process, enabling subsequent cultivation of targeted microorganisms. A 2025 study evaluating Live-FISH on soil microbiomes demonstrated that, while the procedure reduced the number of viable cells by approximately one order of magnitude, 501 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) retained viability and could serve as targets for future cultivation efforts [5]. The study revealed taxon-specific effects, with Planctomycetota and Bacillota demonstrating greater resilience to Live-FISH treatment compared to Acidobacteriota, which were reduced by five orders of magnitude [5]. This selective impact highlights the importance of protocol optimization for specific target microorganisms.

The development of more permeable probe designs and gentler hybridization conditions has been crucial for microbial applications, as many environmental microorganisms possess robust cell walls that limit probe penetration. The integration of catalyzed reporter deposition (CARD-FISH) has significantly improved detection sensitivity for microorganisms with low ribosomal RNA content, while the emergence of CRISPR-based FISH methods (CRISPR-FISH) offers enhanced signal-to-noise ratios and greater design flexibility [7].

For microbial ecology studies, FISH provides unparalleled insights into the spatial organization of microbial communities, enabling researchers to investigate microbial interactions, niche specialization, and community dynamics in situ. When combined with advanced imaging techniques such as confocal laser scanning microscopy and super-resolution microscopy, FISH can reveal the intricate spatial relationships between different microbial taxa and their environment at unprecedented resolution.

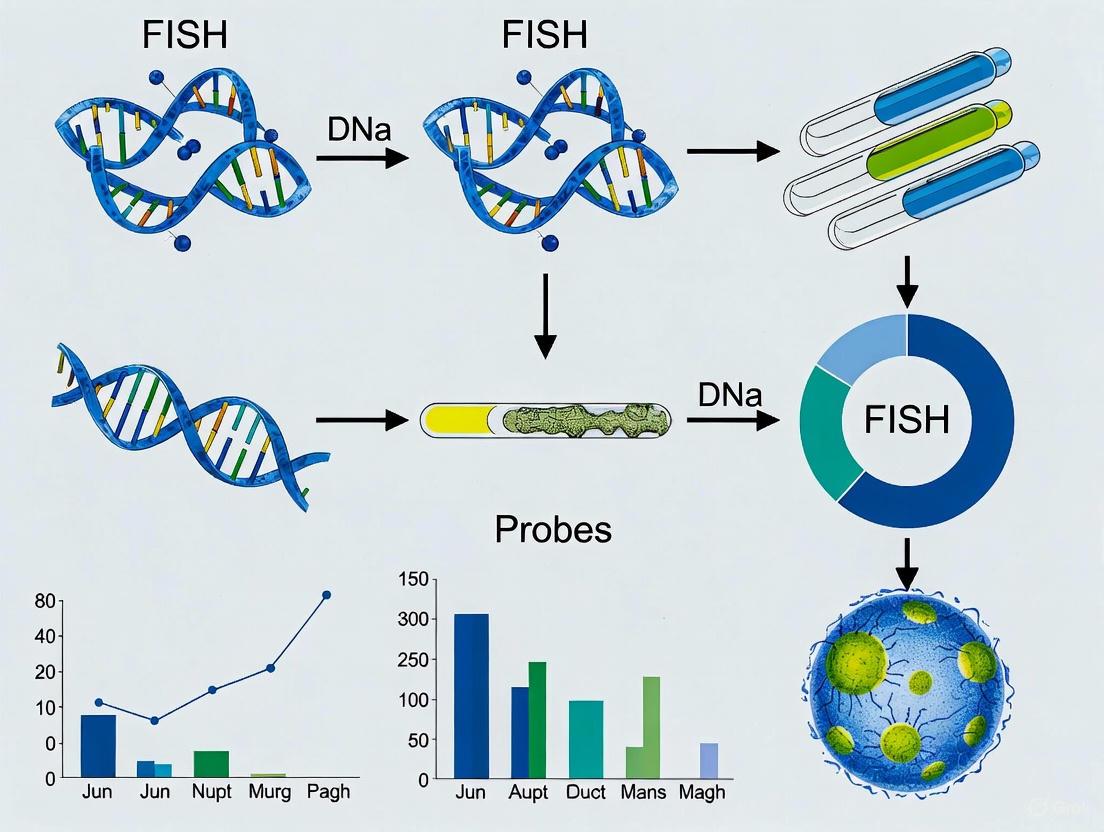

Diagram 1: Microbial FISH Workflow

Advanced FISH Protocols and Methodologies

Live-FISH for Soil Microbiomes

The Live-FISH protocol represents a significant advancement for targeting viable microorganisms in complex environmental samples. The following protocol has been adapted from a 2025 study evaluating Live-FISH applicability on soil microbiomes [5]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Fresh soil samples (temperate topsoil used in original study)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Paraformaldehyde solution (4% in PBS)

- Ethanol series (50%, 80%, 96%)

- Hybridization buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris/HCl, 0.01% SDS, XX% formamide - concentration optimized for specific probe)

- Cy3-labeled rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes

- Washing buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl, 0.01% SDS, XX mM NaCl - concentration matching formamide in hybridization buffer)

- Low-melting-point agarose (0.1% final concentration)

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) system

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 1 g fresh soil in 10 mL PBS. Remove large particles by low-speed centrifugation (500 × g, 2 min).

- Cell Fixation: Fix cells in suspension with paraformaldehyde (4% final concentration) for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Permeabilization: Apply ethanol series (50%, 80%, 96%) for 3 minutes each to enhance cell wall permeability.

- Hybridization: Mix 8 μL cell suspension with 2 μL hybridization buffer containing Cy3-labeled probe (50 ng/μL final concentration). Incubate for 2-3 hours at appropriate hybridization temperature (varies based on probe sequence and formamide concentration).

- Stringency Washes: Incubate samples in pre-warmed washing buffer for 10-15 minutes at hybridization temperature.

- Cell Embedding: Resuspend cells in 0.1% low-melting-point agarose for stabilization during microscopy and sorting.

- Viability Assessment: Apply propidium monoazide (PMA) treatment to differentiate between viable and non-viable cells.

- Microscopy and Cell Sorting: Analyze samples by epifluorescence microscopy or sort labeled cells using FACS for cultivation attempts.

Critical Considerations:

- Taxon-specific effects necessitate protocol optimization for different microbial groups

- Planctomycetota and Bacillota have demonstrated better viability retention than Acidobacteriota [5]

- Hybridization conditions (temperature, formamide concentration) must be optimized for each probe

- PMA treatment is essential for accurate viability assessment

U-FISH: AI-Assisted Signal Detection

The recent development of U-FISH represents a significant advancement in FISH image analysis, addressing the challenge of accurate signal spot detection across diverse imaging conditions [9]. This deep learning method transforms raw FISH images with variable characteristics into enhanced images with uniform signal spots and improved signal-to-noise ratio.

Implementation Protocol:

- Image Acquisition: Collect FISH images according to standard protocols for your specific application.

- Software Installation: Download U-FISH package from available repositories (compatible with Python 3.8+).

- Model Application: Process images through the pre-trained U-Net model (163k parameters) for universal spot detection.

- Parameter Optimization: Utilize fixed parameters across all datasets without need for manual adjustment.

- Analysis: Employ integrated quantification tools for signal counting and localization.

Performance Characteristics:

- Superior accuracy (F1 score: 0.924) compared to existing methods (deepBlink: 0.901, DetNet: 0.886) [9]

- Enhanced generalizability across diverse FISH datasets

- Compatibility with 3D FISH data analysis

- Integration with large language models for simplified user interaction

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of FISH protocols requires specific reagent systems optimized for different applications and sample types. The following table outlines key reagent solutions essential for modern FISH applications in microbial detection research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for FISH Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation Reagents | Paraformaldehyde (4%), Ethanol:Acetic Acid (3:1) | Preserve cellular morphology and nucleic acid integrity | Paraformaldehyde preferred for microbial cells; optimal fixation time varies by cell type |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100, Lysozyme, Proteinase K | Enhance probe accessibility to target sequences | Concentration and duration must be optimized to balance signal and morphology preservation |

| Hybridization Buffers | Standard saline citrate (SSC) with formamide | Create optimal stringency conditions for specific hybridization | Formamide concentration determines stringency; must match probe design characteristics |

| Fluorescent Labels | Cy3, Cy5, FITC, Quantum dots | Provide detection signal through fluorescence emission | Quantum dots offer superior photostability for multiplex applications [6] |

| Signal Amplification Systems | Tyramide signal amplification (TSA), HCR | Enhance detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets | Essential for microorganisms with low rRNA content; may increase background |

| Mounting Media | Antifade reagents (Vectashield, ProLong) | Reduce photobleaching during microscopy | Choice affects signal longevity and compatibility with super-resolution techniques |

| Cell Viability Markers | Propidium monoazide (PMA), SYTO dyes | Differentiate between viable and non-viable cells | Critical for Live-FISH applications and accurate interpretation of results [5] |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The future trajectory of FISH technology points toward several promising directions that will further expand its applications in microbial detection research. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into image analysis workflows represents one of the most significant advancements, with tools like U-FISH demonstrating superior accuracy and generalizability across diverse datasets [9]. These AI-assisted platforms are increasingly being integrated with large language models to create more intuitive user interfaces, making sophisticated analysis accessible to researchers without specialized computational backgrounds.

The continued development of multiplexing capabilities will enable simultaneous detection of dozens or even hundreds of microbial taxa within a single sample, providing unprecedented insights into community structure and spatial organization. Emerging technologies such as CRISPR-based FISH methods (CRISPR-FISH, CRISPR-Hyb) offer promising alternatives with potentially higher signal-to-noise ratios and greater design flexibility [7]. These approaches may overcome current limitations in probe penetration and hybridization efficiency, particularly for environmental microorganisms with robust cell walls.

The application of FISH in spatial-omics represents another frontier, with techniques increasingly being integrated with other molecular approaches to provide multi-omics data within morphological context. The combination of FISH with immunofluorescence (FISH-IF) allows simultaneous visualization of nucleic acids and proteins, while the correlation of FISH data with metagenomic information provides deeper functional insights [8]. These integrated approaches are particularly valuable for understanding the functional capabilities of uncultivated microorganisms in complex environments.

From a technological perspective, the miniaturization and automation of FISH protocols will facilitate higher throughput applications and more standardized results across laboratories. Automated imaging platforms coupled with sophisticated analysis software are already reducing inter-observer variability and accelerating processing times, making FISH more accessible for routine monitoring and clinical diagnostics [7]. As these technologies continue to evolve, FISH will likely become an increasingly integral component of comprehensive microbial characterization workflows across research, clinical, and industrial applications.

Diagram 2: FISH Technology Future Directions

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a powerful molecular cytogenetic technique that uses fluorescent probes to bind specific nucleic acid sequences with high complementarity, allowing for the visualization and identification of microorganisms within their environmental context [1]. The development of FISH has revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling researchers to detect and quantify microorganisms, study their spatial distribution in complex environments like biofilms, and investigate their ecological functions, all without the need for cultivation [11] [12]. The efficacy of FISH technology heavily depends on probe design, which must achieve a delicate balance between sensitivity to target sequences and specificity to avoid cross-hybridizations with unrelated sequences [13].

The evolution of FISH probes has progressed from initial DNA and RNA probes to advanced Nucleic Acid Mimics (NAMs), including peptide nucleic acids (PNA) and locked nucleic acids (LNA), which offer enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and resistance to enzymatic degradation [11] [14]. These advancements have expanded FISH applications from merely identifying microbial community composition using high-copy rRNA targets to detecting specific functional genes, mRNA transcripts, and even single-copy genes with improved signal amplification techniques [12]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for the major FISH probe types, framed within the context of microbial detection research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Probe Types: DNA and rRNA-Targeting Probes

DNA Probes

DNA probes are single-stranded fragments of DNA, typically ranging from 20 to 50 nucleotides, that are complementary to a nucleotide sequence of interest [1]. These probes can be generated through various methods, including nick translation or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using tagged nucleotides, and are typically labelled with fluorophores directly or with targets for antibodies or biotin for indirect detection [1]. For microbial detection, DNA probes are often derived from fragments of DNA that were isolated, purified, and amplified for use in genome projects, with artificial chromosomes (such as BAC) serving as common sources [1].

The specificity of DNA probes varies with their design. Whole-chromosome painting probes hybridize along an entire chromosome and are used to count chromosomes, show translocations, or identify extra-chromosomal chromatin fragments [1]. Locus-specific probe mixtures target specific regions of DNA and are particularly useful for detecting deletion mutations or specific translocations [1]. In comparative studies, commercially produced digoxigenin-labelled DNA probes have demonstrated effectiveness in detecting various DNA viruses, including canine bocavirus 2 (CBoV-2) and porcine circovirus 2 (PCV-2) in infected tissues [15].

rRNA-Targeting Probes

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) has traditionally been the primary target for FISH in microbial detection due to several advantageous characteristics [12]. rRNA is present in all living cells in relatively high copy numbers (10â´â€“10âµ in an actively growing cell), providing abundant natural amplification for detection [12]. Furthermore, as a traditional phylogenetic marker, extensive rRNA sequence databases are available for probe design across diverse taxonomic groups [12].

The procedure for rRNA-targeted FISH typically involves sample fixation (often with paraformaldehyde) to preserve cellular structure and permeabilization to facilitate probe access to the target rRNA [12]. Hybridization is then performed under optimized conditions of temperature, pH, and salt concentration, followed by washing steps to remove unbound probes and visualization via fluorescence microscopy [11]. The accessibility of target sites on rRNA can vary significantly due to secondary and tertiary structures and ribosomal protein interactions, which presents a challenge for consistent hybridization efficiency [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental FISH Probe Types for Microbial Detection

| Probe Characteristic | DNA Probes | rRNA-Targeting Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | DNA sequences (genomic DNA, genes, plasmids) | Ribosomal RNA (16S or 23S rRNA) |

| Copy Number per Cell | Varies (single copy genes to multiple copies) | High (10â´â€“10âµ in active cells) |

| Primary Applications | Gene detection, chromosomal painting, translocation studies | Phylogenetic identification, microbial community analysis |

| Detection Sensitivity | Lower for single-copy genes; requires amplification | High due to natural amplification from abundant rRNA |

| Design Considerations | Specificity to target sequence; probe length (20-50 nt) | Target accessibility; phylogenetic specificity |

| Limitations | Low signal for low-copy targets; requires signal amplification | Dependent on cellular activity and ribosome content |

Advanced Nucleic Acid Mimics (PNA and LNA)

Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Probes

Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNA) represent a significant advancement in FISH probe technology, featuring a neutral pseudopeptide backbone that replaces the sugar-phosphate backbone of natural nucleic acids [14]. This structural modification confers several advantageous properties: higher thermal stability of PNA-DNA/PNA-RNA duplexes, resistance to enzymatic degradation by nucleases and proteases, and flexibility in target selection due to their ability to bind to complementary sequences with high affinity and specificity [11] [14]. The neutral backbone reduces electrostatic repulsion with target nucleic acids, allowing PNA probes to hybridize under lower salt conditions that would destabilize DNA-DNA or DNA-RNA duplexes, which is particularly beneficial for penetrating through the complex cell walls of microorganisms [14].

PNAs have demonstrated particular utility in clinical diagnostics for the rapid identification of bacterial pathogens directly from blood cultures, including Staphylococcus aureus [12]. Their enhanced penetration characteristics make them valuable for detecting microorganisms with tough cell walls that are difficult to permeabilize with standard FISH protocols [14]. Furthermore, PNA-FISH applications have been successfully implemented for the identification of indicator microorganisms using standardized methods, facilitating more efficient monitoring of microbial contamination [12].

Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes

Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) are another class of nucleic acid mimics characterized by a bicyclic sugar ring where a 2'-O,4'-C methylene bridge "locks" the ribose moiety in a C3'-endo conformation [14]. This locked structure enhances base stacking and backbone pre-organization, resulting in unprecedented hybridization affinity toward complementary DNA and RNA sequences [14]. LNA probes demonstrate superior mismatch discrimination capabilities compared to DNA probes, making them exceptionally valuable for applications requiring single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) discrimination [14].

A significant advantage of LNA technology is its compatibility with standard DNA synthesis methods, allowing for the creation of LNA-DNA mixmers (chimeric oligonucleotides containing both LNA and DNA monomers) [14]. This flexibility enables precise optimization of the thermal stability and specificity of FISH probes by strategically incorporating LNA monomers at critical positions within the probe sequence [14]. The high binding affinity of LNA probes allows for the use of shorter probe sequences while maintaining specificity, which can be advantageous for accessing structurally constrained target sites [14].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Nucleic Acid Mimics in FISH Applications

| Performance Metric | PNA Probes | LNA Probes | Traditional DNA Probes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity | High | Very High | Moderate |

| Nuclease Resistance | Excellent | Good | Poor |

| Cell Penetration | Excellent | Moderate | Variable (requires permeabilization) |

| Sequence Specificity | High | Very High (excellent mismatch discrimination) | Moderate |

| Hybridization Conditions | Low salt conditions | Standard FISH conditions | Standard FISH conditions |

| Design Flexibility | Compatible with standard DNA synthesis | Compatible with standard DNA synthesis | High flexibility |

| Best Applications | Tough cell walls, clinical diagnostics | SNP detection, structured targets | General purpose, multiplexing |

Comparative Analysis and Performance Data

The performance of different FISH probe types has been systematically evaluated across various applications and experimental conditions. A comprehensive 2018 study comparing ISH techniques for virus detection found that the detection rate and cell-associated positive area were highest using a commercially available FISH-RNA probe mix compared to self-designed digoxigenin-labelled RNA probes or commercially produced digoxigenin-labelled DNA probes [15]. This superior performance was attributed to the multiple amplification steps and specialized probe design inherent to the FISH-RNA system.

The thermodynamic properties of probe hybridization significantly influence FISH efficiency. Research has demonstrated that the overall Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°overall) is a strong predictor of hybridization efficiency, superior to conventional estimates based on the dissociation temperature of DNA/rRNA duplexes [16]. A threshold ΔG°overall of -13.0 kcal/mol has been proposed as a goal in FISH probe design to maximize hybridization efficiency without compromising specificity [16]. This mechanistic approach considers not only the DNA-RNA hybridization but also intramolecular DNA and rRNA interactions that occur during FISH, providing a more comprehensive understanding of probe affinity [16].

Environmental factors including temperature, buffer composition, salt concentration, and hybridization time critically influence the efficiency and specificity of FISH across all probe types [13]. In standard FISH protocols, hybridization typically occurs at 46°C for 2-3 hours with salt concentration maintained at 750 mM NaCl and 87.5 mM sodium citrate [13]. However, optimal hybridization conditions should be determined individually for each FISH assay, as higher temperatures may increase hybridization rate but risk non-specific binding, while lower temperatures may enhance specificity but reduce hybridization rate [13].

Table 3: Experimental Protocol Parameters for Different FISH Probe Types

| Protocol Parameter | DNA Probes | rRNA Probes | PNA Probes | LNA Probes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Probe Length | 20-50 nucleotides | 15-25 nucleotides | 15-20 nucleotides | 15-25 nucleotides |

| Hybridization Temperature | 46°C | 46°C | 55-65°C | Variable (depends on LNA content) |

| Formamide in Hybridization Buffer | 0-50% | 0-50% | Often omitted | 0-50% |

| Hybridization Time | 2-3 hours | 2-3 hours | 30-90 minutes | 2-3 hours |

| Salt Concentration | 750 mM NaCl, 87.5 mM sodium citrate | 750 mM NaCl, 87.5 mM sodium citrate | Lower salt conditions | 750 mM NaCl, 87.5 mM sodium citrate |

| Wash Temperature | 48°C | 48°C | 55-65°C | Variable (depends on LNA content) |

| Permeabilization Requirement | High | High | Reduced | Moderate to High |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard FISH Protocol for rRNA-Targeted Detection

The following protocol describes the standard procedure for FISH using rRNA-targeted DNA probes for microbial detection in environmental samples:

Sample Fixation: Fix cells or tissue sections with appropriate fixatives (commonly 4% formaldehyde or paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline) for 1-3 hours at room temperature to preserve cellular structure and nucleic acid integrity [11] [1]. For FFPET (formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues), sections of 2-3 µm thickness are typically used [15].

Permeabilization: Treat fixed samples with detergents at 0.1% concentration (Tween-20 or Triton X-100) to enhance tissue permeability and allow probe penetration [11] [1]. For difficult-to-lyse cells, additional enzymatic treatments (lysozyme, proteinase K) may be required [12].

Probe Denaturation: Denature probe mixtures at 85-90°C for 5-10 minutes immediately before use, then place on ice to prevent reannealing [11].

Hybridization: Apply target-specific probe in hybridization buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.01% SDS, 35% formamide) and incubate for 2-3 hours at 46°C [13] [17]. The optimal formamide concentration should be determined empirically for each probe.

Washing: Perform stringent washes with pre-warmed wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, 0.080 M NaCl) at 48°C for 20 minutes to remove nonspecific hybrids and unbound probe molecules [11] [17]. Ethanol washes may be included to reduce autofluorescence [11].

Counterstaining and Visualization: Apply appropriate counterstains (DAPI for DNA, etc.) and mount samples for fluorescence microscopy examination using confocal fluorescence microscopy or wide-field epifluorescence systems [11] [1].

Figure 1: Standard FISH Workflow for Microbial Detection

Live-FISH Protocol for Viable Cell Detection

The live-FISH protocol enables specific hybridization in living bacterial cells, allowing for subsequent cultivation and functional studies:

Sample Preparation: Grow bacterial cultures to late logarithmic growth phase (OD₆₀₀ₙₘ = 0.5-0.8) in appropriate medium. Concentrate environmental samples by filtration through 0.2 µm filters if necessary [17].

Washing: Wash cells three times with 1x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Naâ‚‚HPOâ‚„, 1.8 mM KHâ‚‚POâ‚„) or artificial seawater (ASW) to remove growth medium, avoiding ethanol treatments that would kill cells [17].

Transformation: Resuspend washed cells in 50 µl of 100 mM CaCl₂, then incubate for 15 minutes on ice with 4 ng/µl of fluorescent probe. Perform heat shock at 42°C for 60 seconds, then return briefly to ice [17].

Hybridization: Immediately add 500 µl of pre-warmed (46°C) hybridization buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.01% SDS, 35% formamide) and incubate for 2 hours at 46°C with shaking at 200 rpm [17].

Washing: Pellet cells at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes and resuspend in 500 µl of pre-warmed (48°C) wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, 0.080 M NaCl). Incubate at 48°C for 20 minutes, then centrifuge twice in 500 µl of ice-cold 1x PBS [17].

Cell Sorting and Cultivation: Keep cells in PBS buffer on ice until sorting using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Sort specific taxonomic groups of bacteria and subsequently culture them on appropriate non-selective media [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for FISH Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Formaldehyde, Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Preserves cellular structure and nucleic acid integrity |

| Permeabilization Agents | Tween-20, Triton X-100 (0.1%), Lysozyme, Proteinase K | Enhances cell wall/membrane permeability for probe entry |

| Hybridization Buffers | 0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.01% SDS, 35% Formamide | Creates optimal conditions for specific probe-target hybridization |

| Wash Buffers | 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, 0.080 M NaCl | Removes nonspecific hybrids and unbound probes |

| Probe Types | DNA probes, RNA probes, PNA probes, LNA probes | Targets specific nucleic acid sequences for detection |

| Fluorophores | 6-FAM, Cy3, FITC, Cy5 | Provides detectable signal for microscopy |

| Signal Amplification Systems | Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA), Multiple Labeled Probes | Enhances detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets |

| Commercial Probe Suppliers | Abbott Laboratories, Agilent Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. | Sources of validated probes and FISH reagents |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The development of advanced FISH probe types has enabled increasingly sophisticated applications in microbial detection and research. Single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH or Stellaris RNA FISH) allows for the detection and quantification of individual mRNA molecules in tissue samples through the application of multiple short singly labeled oligonucleotide probes (up to 48 probes targeting a single mRNA molecule) [1]. This technology provides sufficient localized fluorescence to accurately detect and localize each target mRNA, with applications in cancer diagnosis, neuroscience, gene expression analysis, and companion diagnostics [1].

Multiplexed identification techniques such as Combinatorial Labeling and Spectral Imaging FISH (CLASI-FISH) enable simultaneous analysis of multiple microbial taxa by combining combinatorial labeling with spectral imaging to distinguish numerous microbes simultaneously through linear unmixing of fluorophore spectra [11]. While CLASI-FISH offers powerful multiplexing capabilities, it may suffer from internal sensitivity loss and potential probe binding bias, limitations that alternative approaches like Double Labeling of Oligonucleotide Probes for FISH (DOPE-FISH) attempt to address through double signal intensity and stable specificity [11].

The future of FISH probe development continues to evolve with emerging technologies. Expansion-Assisted Iterative (EASI)-FISH has been developed for examining the 3D organization of cell types in thick tissues, particularly valuable for characterizing complex architectures like brain function [11]. Resolution After Single-strand Exonuclease Resection (RASER)-FISH provides robust generation of single-stranded DNA with excellent preservation of chromatin structure and nuclear integrity through exonuclease digestion rather than physical denaturation, resulting in improved hybridization efficiency [11]. These advancements, combined with the ongoing refinement of NAM chemistry and signal amplification strategies, promise to further expand the capabilities of FISH for microbial detection and characterization in complex environments.

Figure 2: FISH Probe Types and Their Primary Applications

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with ribosomal RNA (rRNA) targeting has become a cornerstone technique in microbial ecology and diagnostics. This method provides a powerful approach for the cultivation-independent identification, visualization, and quantification of microorganisms in their natural environments [11] [18]. The technique hinges on the use of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes that bind to complementary rRNA sequences within microbial cells, allowing researchers to detect specific taxa while preserving their spatial context within complex samples like biofilms, tissues, and environmental samples [11] [19]. The selection of an appropriate molecular target is paramount to the success of any FISH experiment, and among available options, ribosomal RNA offers a unique combination of characteristics that make it exceptionally suitable for microbial detection and identification. This application note details the theoretical and practical framework underlying the targeted detection of microorganisms via rRNA-FISH, providing structured data, validated protocols, and key resources to facilitate implementation in research and diagnostic settings.

The Molecular Basis for Targeting rRNA

Ribosomal RNA molecules, particularly the 16S rRNA in prokaryotes and 18S rRNA in eukaryotes, serve as ideal targets for FISH due to their universal distribution, high cellular abundance, and conserved yet variable sequence regions. The rRNA genes are present in all living cells, and the transcribed rRNA molecules can number in the thousands to tens of thousands per cell, providing an naturally amplified target that facilitates sensitive detection without the need for signal amplification in many applications [11] [20]. Furthermore, the genetic sequences of rRNAs contain a mixture of highly conserved regions and variable domains. The conserved areas enable the design of broad-range probes targeting entire domains (e.g., bacteria or archaea), while the variable regions allow for the design of probes with specificity at various taxonomic levels, from genus to species [20] [21].

The advent of comprehensive rRNA databases, such as the Comparative RNA Web (CRW) Site and the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP), has been instrumental in advancing rRNA-targeted FISH [20] [21]. These resources provide extensive collections of aligned rRNA sequences that are crucial for in silico probe design and validation. Probe design software can leverage these databases to identify unique target sequences and check for potential cross-hybridization with non-target organisms, thereby maximizing probe specificity and coverage [20].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Ribosomal RNA as a FISH Target

| Feature | Description | Application in FISH |

|---|---|---|

| High Cellular Abundance | rRNAs can constitute up to 80% of the total cellular RNA, with copy numbers ranging from (10^3) to (10^5) per cell [11]. | Provides a naturally amplified signal, enabling detection without enzymatic amplification and facilitating high sensitivity. |

| Universal Distribution | rRNA genes and their products are found in all living cells, from bacteria and archaea to eukaryotes [21]. | Allows for the development of universal detection assays and the study of diverse, complex microbial communities. |

| Evolutionary Conservation | Contains stretches of sequence that are highly conserved across broad phylogenetic groups [20] [21]. | Enables design of broad-range probes (e.g., for all Bacteria or Archaea) to assess total microbial load or community structure. |

| Variable Sequence Regions | Interspersed with regions of sequence variation that are phylogenetically informative [20] [22]. | Allows for design of group-, genus-, or species-specific probes for taxonomic identification and quantification. |

| Well-Established Databases | Large, curated databases of rRNA sequences (e.g., SILVA, RDP, CRW) are publicly available [20] [21]. | Facilitates systematic, computer-aided design and validation of probes for specificity and coverage before experimental use. |

Quantitative Analysis of Probe Efficacy

The performance of rRNA-targeted FISH probes is governed by thermodynamic principles that can be modeled to predict hybridization behavior. Key parameters include probe specificity, which is the ability to uniquely hybridize to the target group, and probe coverage, the proportion of organisms within the target group that possess the exact probe sequence [20]. A systematic analysis of published probes revealed that many have insufficient coverage or specificity for their intended target group when re-evaluated against modern, expanded rRNA databases [20].

Thermodynamic models, such as those implemented in the mathFISH software, help predict the formamide melting profile of a probe—the concentration of formamide at which the probe dissociates from its target. This is critical for establishing stringent hybridization conditions that maximize specific binding while minimizing non-specific signal [20]. The use of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides is a common strategy to block hybridization to non-targets with slightly mismatched sequences, thereby improving effective specificity [20]. Furthermore, requiring the simultaneous hybridization of two independent probes for positive identification dramatically increases specificity. Research has demonstrated that while highly specific probes can be designed for only about a third of bacterial genera using a single probe, this proportion rises to over two-thirds when two-probe sets are employed [20].

Table 2: Strategies for Enhancing Specificity in rRNA-Targeted FISH

| Strategy | Mechanism | Impact on Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Stringency Control | Manipulation of formamide concentration in the hybridization buffer to control nucleic acid denaturation [20]. | Higher formamide concentrations destabilize mismatched hybrids, suppressing false positives from non-targets. |

| Competitor Probes | Use of unlabeled oligonucleotides that bind to near-perfect matching non-target sequences, blocking probe access [20]. | Diminishes or eliminates signal from non-target organisms, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Multiple Probe Hybridization | Requiring positive signal from two or more independently targeting probes for a positive identification [20]. | Significantly reduces false positives, as the probability of non-specific binding of multiple probes to the same cell is low. |

| Error-Robust Encoding | Using sequential FISH with barcoding schemes that tolerate and correct for single-bit hybridization errors [19]. | Enables highly multiplexed imaging while maintaining high identification accuracy within complex communities. |

Core Protocol: rRNA-Targeted FISH for Microbial Detection

The following protocol provides a standardized workflow for detecting microorganisms using rRNA-targeted FISH. This protocol is adapted from established methods and can be applied to a variety of sample types, including pure cultures, environmental samples, and clinical specimens [11] [20] [18].

Sample Fixation and Permeabilization

Objective: To preserve cellular morphology and integrity while allowing probe penetration. Procedure:

- Harvesting: Collect microbial cells by centrifugation (e.g., 10,000 × g for 5 min) for liquid cultures or by scraping for surface-grown biofilms.

- Washing: Gently resuspend the cell pellet in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and repeat centrifugation.

- Fixation: Resuspend the cell pellet in a fixation solution. For most Gram-negative bacteria, use 3% (v/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 1-4 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. For Gram-positive bacteria, an additional step of 50% ethanol in PBS may be used for improved permeabilization [18].

- Storage: After fixation, pellet the cells, wash with PBS, and finally resuspend in a 1:1 mixture of PBS and ethanol for storage at -20°C. Fixed samples can be stored for several months.

Probe Hybridization

Objective: To facilitate the specific binding of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes to target rRNA sequences. Reagents:

- Hybridization Buffer: Typically contains a high-salt concentration (e.g., 0.9 M NaCl), formamide (concentration must be optimized for each probe), Tris-HCl (pH ~8.0), and a detergent like SDS [20] [18].

- Labeled Probe(s): Oligonucleotide probe(s) (typically 15-25 nucleotides) labeled at the 5'-end with a fluorophore (e.g., Cy3, Cy5, FLUOS, or derivatives). Probes are used at a final concentration of 1-5 µg/mL. Procedure:

- Preparation: Spot fixed samples onto glass slides and allow to air dry.

- Dehydration: Dehydrate the sample by successive immersion in 50%, 80%, and 96% ethanol (3 min each).

- Hybridization: Apply an appropriate volume of hybridization buffer containing the probe(s) to the sample spot and cover with a coverslip to prevent evaporation.

- Incubation: Incubate the slide in a dark, humidified chamber at the appropriate hybridization temperature (typically 46°C) for 1.5 to 3 hours, or overnight.

Post-Hybridization Washing and Visualization

Objective: To remove unbound and non-specifically bound probes, reducing background fluorescence. Reagents: - Wash Buffer: Similar to hybridization buffer but with a lower salt concentration (e.g., 80 mM NaCl) and the same concentration of formamide. Pre-warm before use. Procedure: 1. Washing: Carefully remove the coverslip and immerse the slide in pre-warmed wash buffer. Incubate at 48°C for 10-20 minutes. 2. Rinsing: Briefly rinse the slide with cold, distilled water to remove salt crystals and allow to air dry in the dark. 3. Mounting: Apply an anti-fading mounting medium (e.g., Vectashield or Citifluor) and a coverslip. 4. Visualization: Observe the sample under an epifluorescence or confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with appropriate filter sets for the fluorophore(s) used.

Diagram 1: Core FISH Workflow

Advanced Multiplexing with Sequential FISH

For complex microbial communities, identifying numerous taxa simultaneously is crucial. Sequential error-robust FISH (SEER-FISH) significantly increases multiplexing capability by using multiple rounds of probe hybridization, imaging, and probe dissociation [19]. In each round, a subset of taxa is labeled with one of F fluorophores. Over N rounds, this generates a unique N-bit barcode for each taxon, allowing for the theoretical identification of F^N different microbes [19]. Error-robust encoding schemes with a defined minimal Hamming distance (e.g., HD=4) between barcodes allow for the correction of detection errors that may occur during sequential hybridization, ensuring high accuracy in taxonomic identification [19].

Diagram 2: SEER-FISH Multiplexing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for rRNA-Targeted FISH Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves cellular structure and immobilizes nucleic acids. | Typically used at 2-4% in PBS. Handle in a fume hood. |

| Ethanol | Dehydrating agent and permeabilization aid; also used for sample storage. | A graded ethanol series (50%, 80%, 96%) is used for dehydration. |

| Formamide | Denaturing agent used to control stringency in hybridization and wash buffers. | Concentration is probe-specific; higher % increases stringency. |

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Fluorescently labeled DNA strands complementary to target rRNA sequences. | Designed for specificity; often 15-25 nt long, labeled with Cy3, Cy5, FAM, etc. |

| Competitor Oligonucleotides | Unlabeled probes used to block non-specific binding to off-target sequences. | Designed to bind near-perfect matches in non-target organisms [20]. |

| Hybridization & Wash Buffers | Provide ionic strength and pH for controlled nucleic acid hybridization and washing. | Contain salts (NaCl), buffer (Tris/HCl), detergent (SDS), and formamide. |

| Anti-fading Mountant | Preserves fluorescence and reduces photobleaching during microscopy. | Commercial products like Vectashield or Citifluor are commonly used. |

| Einecs 235-359-4 | Samarium Cobalt (SmCo3)|EINECS 235-359-4 | Samarium Cobalt (SmCo3), EINECS 235-359-4, is a high-performance magnetic intermetallic compound for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| alpha-L-fructofuranose | alpha-L-fructofuranose|Research Use Only |

Ribosomal RNA remains the preeminent target for FISH-based microbial detection due to its unique combination of high cellular abundance, phylogenetic relevance, and the robust framework of databases and thermodynamic models available for probe design. The protocols and strategies outlined here, from basic FISH to advanced multiplexing with SEER-FISH, provide researchers with a powerful set of tools to visualize and identify microorganisms in situ. As sequencing technologies continue to expand our knowledge of microbial diversity, and as microscopy and probe chemistries advance, the utility and application of rRNA-targeted FISH will continue to grow, solidifying its role as an indispensable technique in microbial ecology, diagnostics, and therapeutic development.

Fluorescence *in situ hybridization (FISH) represents a cornerstone molecular cytogenetic technique that enables the detection and localization of specific DNA sequences on chromosomes within cells [23]. Since its inception, FISH technology has diversified significantly, giving rise to numerous advanced variants that address key limitations in sensitivity, multiplexing capacity, and specificity. This technological evolution has been particularly impactful in microbial detection research, where the ability to identify, quantify, and spatially localize microorganisms within complex environmental or clinical samples provides crucial insights into community structure, function, and dynamics.

The expansion of FISH methodologies has transformed microbial ecology and diagnostics, moving beyond simple identification to encompass functional analysis, gene expression monitoring, and intricate spatial profiling within biofilms, tissues, and environmental samples. This overview focuses on three significant FISH variants—CARD-FISH, CLASI-FISH, and DOPE-FISH—each representing distinct technological advancements that address specific research challenges in microbial detection and visualization.

Key FISH Variants: Principles and Applications

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Advanced FISH Variants

| Technique | Full Name | Key Feature | Primary Application in Microbial Research | Sensitivity/Signal Amplification | Multiplexing Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARD-FISH | Catalyzed Reporter Deposition FISH | Enzyme-mediated tyramide signal amplification | Detection of low-abundance targets; quantitative gene expression analysis [24] [25] | Very high (10-20x increase vs monolabeled probes) [26] | Low to moderate |

| DOPE-FISH | Double Labeling of Oligonucleotide Probes FISH | Dual fluorophore labeling on single oligonucleotide | Increased sensitivity for rare targets; simultaneous multicolor detection [26] | ~2x increase vs mono-labeled probes [26] | Moderate |

| CLASI-FISH | Combinatorial Labeling and Spectral Imaging FISH | Combinatorial probe labeling with spectral imaging | High-phylogenetic diversity community analysis; spatial mapping of complex microbiomes [19] | Standard | Very high (theoretically 2F-1 targets with F fluorophores) [19] |

CARD-FISH (Catalyzed Reporter Deposition FISH)

CARD-FISH addresses a fundamental limitation in conventional FISH: detecting targets with low cellular abundance. This method replaces the fluorescently-labeled probe used in standard FISH with an oligonucleotide conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) [26]. After the probe hybridizes to its target sequence, the HRP enzyme catalyzes the deposition of multiple labeled tyramide molecules at the site of hybridization. This signal amplification system generates a much stronger fluorescence signal than directly-labeled probes, enabling detection of target sequences that would otherwise remain undetectable.

The exceptional sensitivity of CARD-FISH, which provides a 10-20 fold increase in signal intensity compared to standard monolabeled probes, makes it particularly valuable for environmental microbiology [26]. It has been successfully applied to investigate gene expression heterogeneity in cyanobacteria at the single-cell level, providing insights into physiological processes within populations of filamentous Trichodesmium and single-celled Synechocystis and Cyanothece [24]. Furthermore, CARD-FISH has been instrumental in protistan ecology, helping to uncover the in situ abundance, feeding modes, and grazing preferences of diverse nanoplanktonic flagellate lineages in aquatic environments [25].

DOPE-FISH (Double Labeling of Oligonucleotide Probes FISH)

DOPE-FISH represents a probe design strategy aimed at enhancing the sensitivity of standard FISH without the complexity of enzymatic amplification. As the name suggests, oligonucleotide probes are labeled with an identical fluorophore at both the 5´- and 3´-end, effectively doubling the number of fluorescent molecules attached to each probe [26]. This straightforward modification yields a nearly twofold increase in sensitivity compared to classic monolabeled FISH probes.

This enhanced sensitivity is advantageous for detecting microorganisms with low ribosomal RNA content or other rare targets. DOPE-FISH has been demonstrated as an effective approach for the simultaneous multicolor detection of six distinct microbial populations in a single assay, facilitating the study of complex microbial community structures [26]. The technique offers a practical balance between improved signal strength and procedural simplicity, serving as a viable alternative when the full amplification power of CARD-FISH is not required.

CLASI-FISH (Combinatorial Labeling and Spectral Imaging FISH)

CLASI-FISH was developed to overcome the multiplexing limitations of conventional FISH, which is typically restricted by the number of spectrally distinct fluorophores. This technique employs a combinatorial labeling strategy, where each microbial taxon is identified not by a single fluorophore, but by a unique combination of fluorophores [19]. Spectral imaging then detects the resulting mixed fluorescence signals, and computational analysis decodes the specific fluorophore combination for each cell, enabling its taxonomic identification.

This approach allows the number of distinguishable taxa to far exceed the number of available fluorophores. Theoretically, with F fluorophores, CLASI-FISH can distinguish up to 2F - 1 different microbial taxa [19]. This extraordinary multiplexing capacity makes CLASI-FISH exceptionally powerful for profiling complex, multi-species microbial communities, such as those found in biofilms, plant rhizospheres, and animal guts, where it can reveal intricate spatial organization and interspecies interactions at micron-scale resolution.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for mRNA CARD-FISH in Cyanobacteria

This protocol, adapted for investigating gene expression heterogeneity in cyanobacteria, outlines the steps for detecting specific mRNA transcripts (e.g., rbcL mRNA) at the single-cell level [24].

Workflow for CARD-FISH Protocol

Key Steps:

- Fixation: Preserve cellular morphology and nucleic acids immediately after collection. Typically done using paraformaldehyde (e.g., 1-4% final concentration) for 1-24 hours at 4°C [24] [25].

- Agarose Coating: Immobilize cells on a solid support (e.g., a microscope slide) by embedding them in a thin, low-melting-point agarose film (0.1-0.8%). This step is crucial for maintaining sample integrity during subsequent treatments [24].

- Permeabilization: Render the cell wall permeable to allow probe entry. For cyanobacteria, this involves an enzymatic treatment, often with lysozyme (0.1-10 mg/mL), to degrade the peptidoglycan layer. Incubation conditions (temperature, duration) must be optimized for the specific cyanobacterial species [24].

- Hybridization with HRP-labeled Probe: Apply the specific oligonucleotide probe conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Hybridization is performed in a buffered saline solution (e.g., containing NaCl, Tris-HCl, formamide, SDS) at an optimized temperature (e.g., 35-46°C) for several hours [24] [26].

- Signal Amplification (Catalyzed Deposition): Incubate the sample with fluorescently labeled tyramide substrates in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. The HRP enzyme catalyzes the covalent deposition of multiple tyramide molecules, leading to significant signal amplification at the probe binding site [26].

- Microscopy and Analysis: Visualize and quantify the fluorescence signals using epifluorescence or confocal microscopy. Image analysis software is then used to assess signal intensity and heterogeneity at the single-cell level [24].

Protocol for Highly Multiplexed SEER-FISH

Sequential error-robust FISH (SEER-FISH) is a cutting-edge method that significantly increases multiplexing capacity through sequential rounds of hybridization and imaging [19]. While related to CLASI-FISH in its goal of high-throughput mapping, it employs a different operational principle.

Table 2: Key Reagents for SEER-FISH and CLASI-FISH Multiplexing

| Reagent / Component | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Taxon-Specific Oligonucleotide Probes | Target 16S or 23S rRNA; designed with stringent criteria for specificity [19] | SEER-FISH / CLASI-FISH |

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Reporters | Binds to primary probes; multiple colors available (e.g., FAM, Cy3, Cy5) [19] | SEER-FISH / CLASI-FISH |

| Dissociation Buffer | Removes hybridized probes after imaging, enabling sequential rounds [19] | SEER-FISH |

| Error-Robust Barcode Codebook | Predefined set of barcodes with minimal Hamming distance for error correction [19] | SEER-FISH |

| Combinatorial Probe Labeling Mix | A unique mixture of fluorophores assigned to each microbial taxon [19] | CLASI-FISH |

Workflow for Sequential FISH Protocol

Key Steps:

- Probe Design and Barcode Assignment: Design oligonucleotide probes targeting the 16S or 23S rRNA of the microbial taxa of interest. Each taxon is assigned a unique multi-round barcode from an error-robust codebook [19].

- Sample Preparation: Affix the complex microbial community (e.g., from a plant rhizosphere) onto a glass coverslip and permeabilize cells for probe access [19].

- Sequential Hybridization and Imaging Cycles:

- Hybridization: Apply a pool of probes for the current imaging round.

- Imaging: Capture multichannel fluorescence images.

- Probe Dissociation: Treat the sample with a dissociation buffer to remove the hybridized probes without damaging the sample. This step is repeated for N rounds (e.g., >25 rounds have been demonstrated) [19].

- Image Alignment and Barcode Identification: Align images from all sequential rounds to account for minor shifts. For each bacterial cell, compile its fluorescence profile across all rounds to determine its unique barcode [19].

- Error-Correction and Taxonomic Identification: Use the error-robust encoding scheme (e.g., a minimal Hamming distance of 4) to correct for detection errors and accurately assign taxonomic identity to each cell [19].

- Spatial Profiling: Map the identified taxa back to their original locations to reconstruct the spatial organization of the microbial community at micron-scale resolution and analyze microbial biogeography [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced FISH Methodologies

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Probes | Hybridize to target nucleic acid sequences; backbone of all FISH techniques. | monoProbes, dopeProbes (DOPE-FISH), HRP-Probes (CARD-FISH), Click-labeled probes [26] |

| Fluorophores | Generate detectable fluorescence signal. | FAM, Cyanine 3 (Cy3), Cyanine 5 (Cy5) [26] [19] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Enzyme for signal amplification in CARD-FISH; catalyzes tyramide deposition [26] | CARD-FISH |

| Tyramide Substrates | Fluorescently-labeled tyramide; substrate for HRP in amplification reaction [26] | CARD-FISH |

| Permeabilization Agents | Disrupt cell walls/membranes to allow probe entry. | Lysozyme (for bacteria) [24], detergent solutions |

| Signal Amplification Systems | Enhance weak fluorescence signals for low-abundance targets. | Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) in CARD-FISH [26] |

| N-Isohexadecylacrylamide | N-Isohexadecylacrylamide|Hydrophobic Acrylamide Monomer | N-Isohexadecylacrylamide is a hydrophobic monomer for research on polymers, coatings, and drug delivery. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 2-Ethylhexyl crotonate | 2-Ethylhexyl crotonate, CAS:7299-92-5, MF:C12H22O2, MW:198.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The diversification of FISH technologies into specialized variants like CARD-FISH, DOPE-FISH, and CLASI-FISH has profoundly enhanced the toolbox available to researchers studying microbial communities. Each variant addresses a specific set of challenges: CARD-FISH provides the sensitivity required for detecting low-abundance targets and analyzing gene expression, DOPE-FISH offers a simple yet effective sensitivity boost for standard applications, and CLASI-FISH and related sequential methods break through multiplexing barriers to map complex communities.

These advancements allow scientists to move beyond mere detection to conduct sophisticated analyses of microbial community structure, function, and spatial dynamics in their native contexts. The ongoing development of more robust protocols, automated platforms [27], and increasingly multiplexed imaging approaches [19] promises to further solidify the role of FISH technologies as indispensable instruments in microbial ecology, diagnostic pathology, and drug development. The future of microbial detection research will undoubtedly be shaped by the continued integration and refinement of these powerful FISH variants.

Executing FISH: Optimized Protocols and Cutting-Edge Applications in Microbial Detection

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a powerful cytogenetic technique that enables the detection and localization of specific DNA or RNA sequences within intact cells, preserved tissue sections, or chromosomes. By combining molecular genetics with conventional cytogenetics, FISH provides high-resolution spatial and temporal information about genetic abnormalities, gene expression, and microbial identity in complex samples. This application note details the critical steps in the FISH workflow, from sample preparation and fixation through probe hybridization and final visualization, with particular emphasis on its application in microbial detection research. The protocols and methodologies outlined herein are designed to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in implementing robust and reproducible FISH assays for their investigative and diagnostic needs.

In microbial ecology and diagnostics, FISH is indispensable for identifying, quantifying, and localizing yet-uncultured bacteria within their natural environments. The technique typically targets the highly conserved 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which is present in all living organisms and provides a genetic signature for taxonomic classification. Signature sequences unique to specific taxonomic groups are identified, and complementary DNA probes labeled with fluorescent dyes are synthesized. Under controlled hybridization conditions, these probes bind specifically to the rRNA of target microorganisms, allowing not only for their staining but also for spatial localization within samples such as biofilms, consortia, or attached to surfaces. A critical prerequisite for successful microbial detection is the immediate preservation of samples with a fixative (e.g., formaldehyde) after collection to maintain the natural biocoenosis and spatial distribution of the microbes [28].

Critical Steps in the FISH Workflow

The FISH procedure can be broken down into several key phases, each containing critical steps that influence the success and accuracy of the assay.

Sample Preparation and Fixation

Proper sample preparation is foundational for preserving morphology and nucleic acid integrity.

- Sample Collection: Samples can vary widely, including cultured cells, peripheral blood, bone marrow, urine, Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues, or environmental samples like water, soil, or biofilms [29] [30]. For microbial samples, immediate fixation is crucial post-collection.

- Fixation: Fixation arrests cellular processes and preserves the sample's structural integrity. Common fixatives include Carnoy's solution for cell pellets or 4% paraformaldehyde for environmental microbes and tissues [29] [28] [31].

- Slide Preparation: Fixed cell pellets are resuspended in fixative and dropped onto microscope slides. For FFPE tissues, sections are mounted on slides, baked, and deparaffinized with organic solvents before the assay [29].