From Genes to Function: Integrating Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics for Advanced Microbial Ecology and Precision Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of metagenomics and metatranscriptomics and their transformative role in microbial ecology and clinical applications.

From Genes to Function: Integrating Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics for Advanced Microbial Ecology and Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of metagenomics and metatranscriptomics and their transformative role in microbial ecology and clinical applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles distinguishing DNA-based community profiling from RNA-driven functional activity analysis. The scope extends to detailed methodological workflows, from sample preparation and sequencing platforms to data analysis pipelines for taxonomic and functional profiling. It addresses key challenges such as standardization, host contamination, and data integration, while also presenting troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, the article examines validation through multi-omic integration and comparative analysis, highlighting real-world applications in human health, disease diagnostics, and therapeutic development, thereby offering a roadmap for leveraging these technologies in precision medicine.

Decoding the Microbial Blueprint: Core Concepts and Divergent Roles of Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

In the field of microbial ecology, metagenomics and metatranscriptomics represent complementary yet distinct methodological paradigms for investigating complex microbial communities. Metagenomics functions as a functional blueprint mapper, analyzing the collective DNA of microbial communities to reveal their taxonomic composition and genetic potential [1] [2]. This approach provides a comprehensive inventory of "what microorganisms can do" by cataloging the inherited functional capabilities encoded in their genomes [3]. In contrast, metatranscriptomics serves as a real-time activity monitor, capturing the entire RNA transcript pool to reveal which genes are actively expressed at a specific point in time and under particular environmental conditions [1] [4]. This dynamic perspective reveals "what microorganisms are actually doing" in response to their environment, host interactions, or ecological perturbations [5].

The distinction between these paradigms is not merely technical but fundamentally conceptual—where metagenomics reveals potential, metatranscriptomics reveals action. This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding their technical requirements, application landscapes, and implementation protocols to guide researchers in selecting and deploying these powerful technologies effectively.

Technical Foundations: Methodological Comparisons

Sample Preparation and Handling

The initial sample handling phase reveals fundamental differences between these approaches, dictated by the distinct biochemical properties of their target molecules.

Metagenomics Sample Preparation: This approach focuses on environmental samples (soil, water, digestive contents) and utilizes methods optimized for comprehensive DNA recovery. The bead-beating method is commonly employed, which mixes samples with beads under high-speed agitation to break cell walls via mechanical force and release DNA [1]. This method is simple, effective for diverse cell types, and easily scalable for processing large sample volumes. The relative stability of DNA allows for more flexible sample handling and storage conditions compared to RNA-based methods.

Metatranscriptomics Sample Preparation: This method requires rapid stabilization of RNA due to its inherent instability and susceptibility to degradation. Immediate flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen is essential post-collection [4] [5]. For processing, enzymatic digestion is preferred, where specific enzymes disrupt cell-cell junctions to disperse cells while minimizing RNA damage [1]. The requirement for RNA integrity preservation often necessitates specialized preservation solutions such as DNA/RNA Shield and stringent cold-chain management throughout processing [4].

Sequencing Platforms and Technical Specifications

The choice of sequencing platform significantly impacts the resolution, accuracy, and cost of both metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses.

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Comparison for Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

| Technology | Read Type | Key Applications | Accuracy/Features | Cost per Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomics Platforms | ||||

| Illumina NovaSeq | Short reads (2×250 bp) | Species identification, community composition | High accuracy, minimal errors | ~¥735 [1] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long reads (>100 kb) | Full-length 16S rRNA analysis, novel pathogen discovery | Enables complete genome reconstruction | ~Â¥2,940 [1] |

| Metatranscriptomics Platforms | ||||

| RNA-Seq (Illumina) | Short reads | Differential expression analysis, microbial activity profiling | High throughput, unmatched accuracy | ~Â¥1,050 [1] |

| SMART-Seq (PacBio) | Full-length transcripts | Alternative splicing, gene fusions, complex transcriptomes | Captures complete transcript structures | ~Â¥1,400 [1] |

Platform selection must align with research objectives: short-read platforms offer cost-efficiency for large-scale comparative studies, while long-read technologies provide superior resolution for discovering novel organisms or characterizing complex transcriptional events [1] [6].

Bioinformatic Processing Pipelines

The computational workflows for analyzing metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data differ significantly in their objectives and implementation.

Metagenomic Analysis typically involves quality control (FastQC), assembly (metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT), binning into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), and functional annotation against databases such as KEGG and SEED [3] [7]. The creation of MAGs represents a particular advancement, enabling researchers to reconstruct genomes of uncultured microorganisms directly from environmental samples [7].

Metatranscriptomic Analysis requires specialized processing including rRNA depletion using custom oligonucleotides, quality control, transcript assembly (Trinity, MEGAHIT), quantification (Salmon), and functional annotation (eggNOGmapper, KEGG) [4] [5]. For challenging samples like human skin, rigorous contamination control and unique minimizer thresholds are essential to filter false-positive taxa [4].

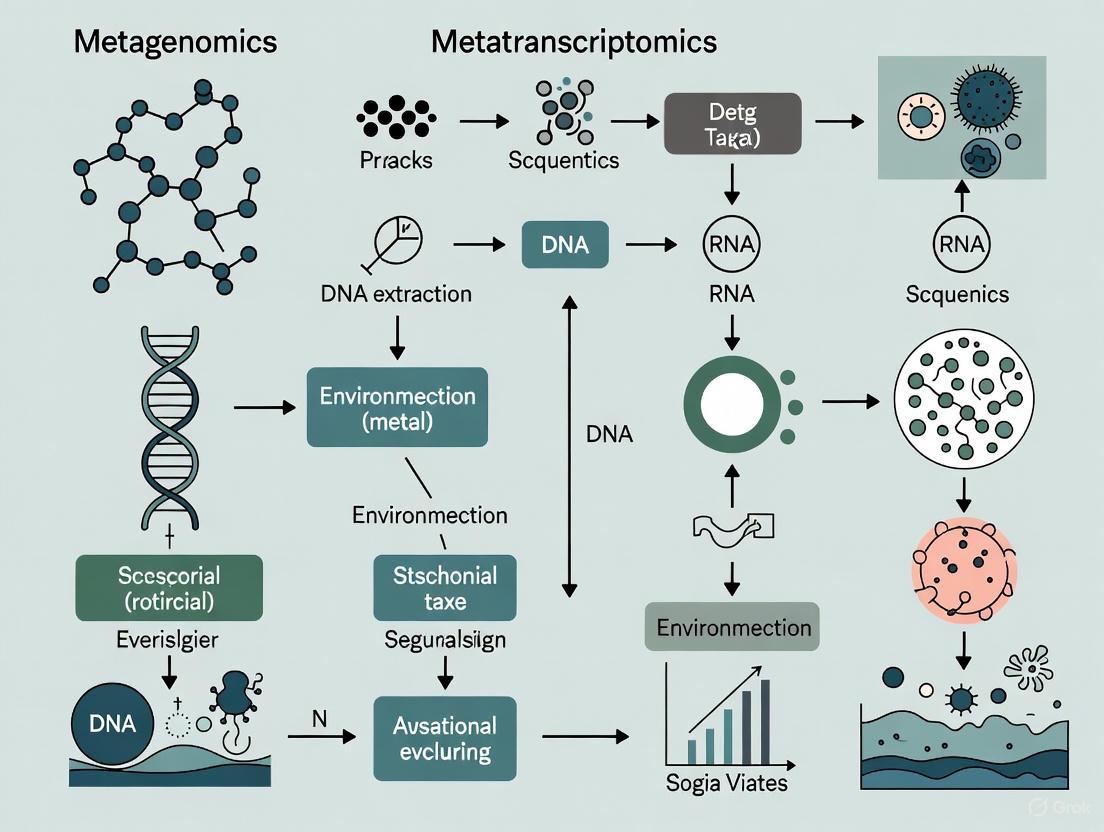

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows for Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics. This diagram illustrates the divergent technical pathways from sample collection to data interpretation, highlighting the DNA-centric approach of metagenomics (blue) versus the RNA-centric approach of metatranscriptomics (red).

Application Scenarios: Comparative Case Studies

Municipal Wastewater Monitoring (Metagenomics Case Study)

Research Objective: Gauthier et al. implemented a metagenomic approach to establish a "tracking-assembly" workflow for real-time, strain-level monitoring of low-abundance intestinal pathogens in municipal wastewater inflows in Quebec City, Canada [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Wastewater samples collected from municipal inflows from September 2023 to January 2024

- DNA Extraction: Bead-beating method for comprehensive cell lysis

- Sequencing: Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing technology

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Species binning of reads using Kraken2

- Reference-guided assembly using reference genomes as templates

- Reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)

Key Findings: The researchers successfully reconstructed genomes with 95-99% completeness from low-abundance intestinal pathogens representing just 0.1-1% of total reads. Results demonstrated that abundances of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and non-typhoidal Salmonella (ENTS) were significantly elevated approximately one month earlier than subsequent public food recalls [1]. This demonstrates metagenomics' power as a "functional blueprint mapper" by identifying pathogen-specific genetic elements and enabling early warning detection without culturing.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Mechanisms (Metatranscriptomics Case Study)

Research Objective: Investigate the relationship between human gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by analyzing real-time gene expression of gut microbiota to reveal their functional roles in inflammation [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Stool samples from 535 IBD patients and healthy controls, immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen

- RNA Extraction: Combined thermal lysis and silica bead method, followed by DNase I treatment

- rRNA Depletion: Removal of ribosomal RNA to enrich mRNA

- Sequencing: NovaSeq PE150 sequencing producing >20 million reads per sample

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control with Trimomatic

- Quantification with Salmon

- Functional annotation with eggNOG/KEGG databases

Key Findings: Metatranscriptomics revealed significantly decreased transcriptional activity of butyrate-producing bacteria (Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia intestinalis) in patients' intestines, while Ruminococcus gnavus and E. coli were upregulated [5]. The integration of transcriptomic data with metabolomic profiles (LC-MS/MS) showed that aromatic amino acid metabolic pathway activity correlated with indole-3-acetic acid and secondary bile acid levels. These metabolites inhibited Th17 inflammation via AHR/FXR pathways, providing a mechanistic link between microbial metabolic activities and host inflammatory responses [5].

Skin Microbiome Activity (Integrated Metagenomics-Metatranscriptomics Study)

Research Objective: Develop a robust skin metatranscriptomics workflow to identify active species and microbial functions in situ across five skin sites in 27 healthy adults, comparing metatranscriptomic findings with metagenomic data [4].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Swabs from five skin sites (scalp, cheek, volar forearm, antecubital fossae, toe web)

- Sample Preservation: Immediate preservation in DNA/RNA Shield

- RNA Processing: Bead beating, rRNA depletion using custom oligonucleotides, direct-to-column TRIzol purification

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing targeting 1 million microbial reads per sample

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Customized workflow using skin-specific microbial gene catalog (iHSMGC)

- Rigorous control of 'kitome' and taxonomic misclassification artifacts

- Application of unique minimizer thresholds to identify false positives

Key Findings: The study revealed a notable divergence between transcriptomic and genomic abundances. Staphylococcus species and the fungi Malassezia had an outsized contribution to metatranscriptomes at most sites, despite their modest representation in metagenomes [4]. Gene-level analysis identified diverse antimicrobial genes transcribed by skin commensals in situ, including several uncharacterized bacteriocins. Correlation of microbial gene expression with organismal abundances uncovered more than 20 genes that putatively mediate interactions between microbes [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Microbial Features Across Case Studies

| Study Focus | Methodology | Key Microbial Findings | Functional Insights | Technical Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Pathogen Monitoring [1] | Long-read metagenomics | Reconstructed MAGs with 95-99% completeness from 0.1-1% abundance pathogens | Identified STEC & ENTS peaks 1 month before food recalls | Tracking-assembly workflow for strain-level monitoring |

| IBD Gut Microbiome [5] | Metatranscriptomics | ↓ Butyrate producers; ↑ R. gnavus & E. coli | Linked aromatic amino acid metabolism to inflammation via AHR/FXR | Random forest model (AUC=0.87) for IBD activity prediction |

| Skin Microbiome [4] | Paired metagenomics & metatranscriptomics | Staphylococcus & Malassezia activity > abundance | Discovered 20+ putative microbe-microbe interaction genes | Clinical skin metatranscriptomics workflow with high reproducibility |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic studies requires specialized reagents and materials optimized for different sample types and research objectives.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield [4] | Metatranscriptomics | Immediate stabilization of RNA at collection | Prevents degradation; essential for low-biomass samples |

| Bead Beating Matrix [1] | Metagenomics | Mechanical cell lysis for DNA release | Effective for diverse cell types; scalable for large volumes |

| Custom rRNA Depletion Oligos [4] | Metatranscriptomics | Enrichment of mRNA by removing ribosomal RNA | Increases mRNA sequencing depth 2.5-40× [4] |

| TRIzol Purification Reagents [4] | Metatranscriptomics | Direct-to-column RNA purification | Preserves RNA integrity; minimizes handling losses |

| Internal RNA Standards [8] | Quantitative Metatranscriptomics | Enables absolute transcript quantification | Saccharolobus solfataricus RNA used for cross-validation |

| Mock Community Standards [4] | Quality Control | Protocol validation and reproducibility | Assesses technical variability (median correlation >0.98) |

| cis-3,4-Di-p-anisyl-3-hexene-d6 | cis-3,4-Di-p-anisyl-3-hexene-d6|Stable Isotope Labeled | cis-3,4-Di-p-anisyl-3-hexene-d6 stable isotope for metabolic and analytical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 6-Chloro-7-iodo-7-deazapurine | 4-chloro-5-iodo-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine | RUO | High-purity 4-chloro-5-iodo-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine for anticancer & kinase research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Strategic Technology Selection Framework

Research Objective Alignment

Choosing between metagenomics and metatranscriptomics requires careful consideration of research questions, sample types, and resource constraints.

Select Metagenomics When:

- The objective is comprehensive taxonomic cataloging of microbial communities

- Characterization of functional potential (inherited capabilities) is desired

- Studying genetic elements (antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factors) in environments

- Working with samples where RNA preservation was not possible

- Budget constraints prioritize lower-cost approaches (~Â¥735/sample for Illumina) [1]

Select Metatranscriptomics When:

- Research aims to understand real-time microbial responses to environmental stimuli

- Investigating host-microbe interactions at the functional level

- Differentiating active from dormant community members

- Studying rapid ecological changes or temporal dynamics

- Research requires insights into actual gene expression rather than potential [2]

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches

For complex research questions, integrating metagenomics with metatranscriptomics provides complementary insights that surpass either method alone. In beef cattle rumen studies, integrated approaches revealed that metagenomes were more conserved among individuals than metatranscriptomes, suggesting higher inter-individual functional variations at the RNA level [9]. This integration identified breed-specific differential rumen microbial features between cattle with high and low feed efficiency, demonstrating how host genetics interacts with microbial functions [9].

Diagram 2: Technology Selection Framework Based on Research Objectives. This decision pathway illustrates how specific research questions determine the choice between metagenomics (blue) and metatranscriptomics (red), with integration (green) providing the most comprehensive insights.

Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics offer powerful, complementary lenses for investigating microbial communities. As "functional blueprint mapper," metagenomics provides comprehensive inventories of microbial membership and inherited capabilities, while as "real-time activity monitor," metatranscriptomics captures dynamic functional responses to environmental and host factors [1] [2].

Strategic implementation requires matching technological strengths to research objectives: metagenomics for cataloging potential and metatranscriptomics for capturing activity. For maximal insight, integrated multi-omics approaches can connect genetic capacity with actual function, as demonstrated in studies of wastewater monitoring [1], IBD mechanisms [5], and skin microbiome dynamics [4]. As these technologies continue evolving with improvements in long-read sequencing, single-cell resolution, and computational analytics, their synergistic application will further illuminate the functional dynamics of microbial ecosystems across human health, environmental science, and biotechnology.

In microbial ecology, understanding the structure and function of complex microbial communities is fundamental. Two complementary approaches have emerged as cornerstones of this research: metagenomics, which sequences total community DNA to profile the genetic potential of a community, and metatranscriptomics, which sequences expressed community RNA to reveal actively transcribed functions [10] [11]. Metagenomics answers the question "Who is present and what could they do?" by cataloging all genomic DNA, including that from dormant cells, spores, and extracellular DNA. In contrast, metatranscriptomics addresses "What is the community actively doing?" by capturing the messenger RNA (mRNA) fraction, providing a snapshot of real-time gene expression and metabolic activity [3]. This Application Note delineates the theoretical and practical distinctions between these approaches, providing a framework for their application in microbial ecology and drug discovery. We present quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and decision-making tools to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate method for their scientific inquiries.

Comparative Analysis: Metagenomics vs. Metatranscriptomics

The choice between DNA and RNA sequencing profoundly impacts the biological interpretation of a microbiome. The core distinction lies in the target molecule: DNA represents the total community membership and its functional potential, while RNA represents the active community members and their expressed functions [12].

RNA molecules degrade more quickly than DNA, meaning RNA-based analysis primarily captures signals from living, active cells, excluding DNA from dead cells, lysed cells, or extracellular sources that can constitute 40–90% of the total DNA pool in an environmental sample [13]. Consequently, community composition derived from DNA (metagenomics) often differs significantly from that derived from RNA (metatranscriptomics), with the latter providing a picture of which members are functionally engaged at the time of sampling [14] [12].

Table 1: Core Conceptual and Practical Differences Between Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

| Feature | Metagenomics (Total Community DNA) | Metatranscriptomics (Expressed Community RNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Genomic DNA (from all cells) | Total RNA, primarily mRNA (from active cells) |

| Biological Question | "Who is present and what is the functional potential?" | "What functions are being actively expressed?" |

| Information Provided | Taxonomic census, presence of functional genes | Gene expression levels, active metabolic pathways |

| Influenced By | DNA from dead, dormant, and active cells; extracellular DNA | Transcriptionally active cells only |

| Functional Insight | Predicted function based on gene presence | Actual function based on gene expression |

| Detection of RNA Viruses | No | Yes |

Empirical studies consistently highlight the divergence in insights gained from these two approaches. For instance, in a study of urban bioswale soils, DNA and RNA analyses both confirmed that engineered soils had distinct bacterial communities compared to non-engineered soils. However, the RNA-based analysis provided a sharper picture of the active community, revealing that total bacterial communities were poor predictors of expressed community diversity, a critical consideration when evaluating ecological functioning [14]. Similarly, in the plant rhizosphere, DNA-based community analysis disproportionately emphasized certain phyla, while RNA-based analysis (representing protein synthesis potential) highlighted the importance of known root associates that were actively transcribing in that environment [12].

From a technical performance standpoint, total RNA sequencing (total RNA-Seq) has been shown to be more accurate than metagenomics for taxonomic identification at equal sequencing depths, and can maintain this accuracy even at sequencing depths almost an order of magnitude lower [13]. Another benchmarking study, meta-total RNA sequencing (MeTRS), demonstrated superior sensitivity and linearity for detecting both bacteria and fungi compared to shotgun metagenomics and amplicon-based sequencing, while requiring a ~20-fold lower sequencing depth than shotgun metagenomics [15].

Table 2: Empirical Findings from Comparative Studies in Different Environments

| Environment | Insights from DNA (Metagenomics) | Insights from RNA (Metatranscriptomics) | Key Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Bioswale Soils | Revealed distinct phylogenetic diversity and presence of taxa linked to pollutant degradation. | Showed enriched expression of functional genes for carbon fixation, nitrogen cycling, and contaminant degradation. | [14] |

| Human Cervix | Detected a wider number of bacterial genera. | Fewer genera contributed to most transcripts; detected twice as many virus genera, including RNA viruses. | [16] |

| Plant Rhizosphere | Provided a census of total microbial membership, including dormant cells. | Uncovered fine-scale differences in active genera and elevated activity of carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism pathways. | [12] |

| Human Gut (Mock Community) | Suffered from a lack of sensitivity, especially for fungi. | Detected all expected species with a linear response over a wider dynamic range; more accurately reported fungal abundances. | [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metagenomic Sequencing for Community Profiling

This protocol details the steps for shotgun metagenomic sequencing to assess the taxonomic composition and functional potential of a microbial community.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Sample Collection: Collect samples (e.g., soil, water, human swabs) in sterile containers. Immediately flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen or place on dry ice for transport to preserve integrity [14] [12].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use a commercial kit designed for total nucleic acid extraction (e.g., Roche MagNA Pure LC, MoBio PowerSoil kit) to lyse cells and isolate total DNA. For soils, a combined thermal lysis and silica bead beating method is effective [14] [5]. Quantify DNA yield using a fluorometric assay (e.g., QuantiFluor, Promega).

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Library Prep: For shotgun metagenomics, use a library preparation kit such as the Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit, starting with 1 ng of input DNA as per manufacturer's instructions [16]. This step fragments the DNA and adds indexed adapters for multiplexing.

- Sequencing: Normalize libraries to 1 nM, pool, and sequence on an Illumina NextSeq500 or similar platform using a 2 x 150 bp paired-end sequencing run [16].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Use Trimmomatic to remove adapters and quality-trim reads [16]. Optionally, remove host-derived reads by mapping to a host reference genome (e.g., human GRCh38) using a tool like NextGenMap [16].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Classify high-quality, non-host reads using a taxonomic classifier such as Kraken2 against a RefSeq database of bacterial and viral genomes [16]. Alternatively, for functional potential analysis, assemble reads into contigs and annotate genes against functional databases like KEGG or eggNOG.

Protocol 2: Metatranscriptomic Sequencing for Active Community Analysis

This protocol outlines the procedure for total RNA sequencing to profile the actively expressed genes in a microbial community.

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction:

- Rapid Collection and Stabilization: The rapid degradation of RNA necessitates immediate stabilization. Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen within minutes of collection [5] [12]. Use RNA-specific preservatives (e.g., RNA later) if immediate freezing is not possible.

- Total RNA Extraction: Employ a commercial total RNA extraction kit. For challenging samples like stool or soil, the classical hot-phenol method provides high yields with minimal bias [15]. Treat extracts with DNase I to remove contaminating genomic DNA [14] [5]. Assess RNA integrity using an RNA Integrity Number (RIN); a RIN ≥5 is often acceptable for microbiome studies [11].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- rRNA Depletion: Since 80-98% of cellular RNA is ribosomal RNA (rRNA), a depletion step is crucial to enrich for mRNA. Use a ribosomal depletion kit such as the Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome kit [11].

- Stranded cDNA Library Prep: Use a stranded total RNA-Seq library kit (e.g., Takara Bio Smarter stranded total RNA-seq kit) [16]. This protocol includes cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. To control for DNA contamination, a parallel library can be prepared from a DNase-treated aliquot of the RNA sample [16].

- Sequencing: Normalize cDNA libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq PE150) to a depth of >20 million reads per sample to ensure adequate coverage of the transcriptome [5].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Quality control and adapter trimming with tools like Trimomatic or Cutadapt [5] [16].

- Taxonomic/Functional Assignment: For taxonomic profiling of the active community, tools like Kraken2/Bracken can be used [3]. For functional analysis, quality-controlled reads can be mapped to reference genomes or assembled de novo (using MEGAHIT or Trinity) [5]. Quantify transcript abundance with Salmon and perform functional annotation using KEGG, SEED, or eggNOG-mapper to identify active metabolic pathways [14] [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel paths for metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis, highlighting the key experimental and computational steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents and kits is critical for the success of microbiome studies. The table below lists essential solutions for nucleic acid extraction and library preparation from complex microbial samples.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Kits for Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| PowerSoil DNA/RNA Kit (MoBio/QIAGEN) | Concurrent extraction of DNA and RNA from environmental samples. | Effective for challenging, inhibitor-rich samples like soil and stool, ensuring high yield and purity. |

| MagNA Pure LC Instrument (Roche) | Automated extraction of total nucleic acids. | Provides standardized, high-throughput isolation of total nucleic acid from swab and liquid samples. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) | Shotgun metagenomic library preparation. | Enables rapid preparation of multiplexed, adapter-ligated sequencing libraries from low-input (1 ng) DNA. |

| Ribo-Zero Plus Microbiome Kit (Illumina) | Depletion of ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples. | Critical for metatranscriptomics, enriches for mRNA by removing bacterial and eukaryotic rRNA. |

| SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit (Takara Bio) | Preparation of stranded RNA-seq libraries. | Facilitates construction of sequencing libraries from total RNA, including degraded and low-input samples. |

| Turbo DNA-free Kit (ThermoFisher) | Removal of contaminating genomic DNA from RNA samples. | Ensures pure RNA template for cDNA synthesis, preventing false positives in metatranscriptomics. |

| Phytanic acid methyl ester | Phytanic Acid Methyl Ester | High Purity | RUO | Phytanic acid methyl ester for lipid metabolism & peroxisomal disorder research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| DL-Methionine sulfone | DL-Methionine sulfone | High Purity | For Research Use | DL-Methionine sulfone for research. A key metabolite in methionine oxidation studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The interrogation of total community DNA and expressed community RNA provides distinct, yet powerfully complementary, vistas of microbial ecosystems. Metagenomics offers a comprehensive census of membership and functional capacity, forming a foundational understanding of "what could happen." Metatranscriptomics, by contrast, captures the dynamic expression of this potential, revealing "what is happening" at a specific moment in time. The decision to use one or both approaches must be driven by the specific biological question. For profiling a community's stable taxonomic structure and gene content, metagenomics is the tool of choice. For investigating active responses to environmental stimuli, host-disease interactions, or the functional roles of specific microbial consortia, metatranscriptomics is indispensable. As demonstrated in diverse environments—from urban soils to the human gut—integrating both DNA and RNA perspectives yields a more holistic and mechanistically insightful understanding of microbial communities, ultimately accelerating discovery in ecology, medicine, and biotechnology.

In microbial ecology, understanding the complex functions of microbial communities requires moving beyond a simple census of inhabitants. The fields of metagenomics and metatranscriptomics provide complementary lenses to answer progressively deeper biological questions. Metagenomics reveals the taxonomic composition and genetic potential of a community—addressing "Who is there and what can they do?" In contrast, metatranscriptomics captures the pool of expressed mRNA transcripts, illuminating the genes that are actively being transcribed under specific conditions—answering "What are they actually doing now?" [17] [4]. This functional activity is a more direct indicator of the microbiome's physiological state, as it sits at the nexus of an organism’s genetic blueprint and its environmental stimuli [17]. The integration of these approaches is revolutionizing our understanding of host-microbe interactions, biogeochemical cycling, and the functional dynamics of ecosystems ranging from the human gut to aquatic environments.

The distinction between potential and activity is not merely academic; it is biologically profound. Metagenomic signals originate from both living and dead cells, and genes can remain silent in living microbes. Metatranscriptomics, by assaying mRNAs, provides a snapshot of the metabolic processes actively being utilized in response to immediate environmental cues [4]. For instance, a microbe might possess the genetic potential to break down a complex carbohydrate, but it will only express the requisite enzymes if that carbohydrate is present. This conceptual shift is accompanied by the recognition that to achieve a more comprehensive picture, metagenomics must be combined with metatranscriptomics and other omics technologies [17].

Comparative Analysis of Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

The following table summarizes the core differences between these two approaches in addressing ecological questions.

Table 1: Core differences between metagenomics and metatranscriptomics

| Feature | Metagenomics | Metatranscriptomics |

|---|---|---|

| Molecule Targeted | Total DNA (genetic blueprint) | Total mRNA (expressed transcripts) |

| Primary Question | "Who is there and what can they do?" [4] | "What are they actually doing now?" [4] |

| Output | Taxonomic profile, functional gene potential | Gene expression profile, active functional pathways |

| Temporal Resolution | Stable potential; reflects genetic capacity | Dynamic activity; snapshot of real-time response |

| Key Limitation | Infers function but cannot confirm activity [4] | Technically challenging (e.g., low RNA stability, host contamination) [4] |

A compelling example of their divergence comes from skin microbiome studies. Research has identified a notable disconnect between transcriptomic and genomic abundances. Specifically, Staphylococcus species and the fungi Malassezia had an outsized contribution to metatranscriptomes at most skin sites, despite their modest representation in metagenomes [4]. This indicates these taxa are metabolically highly active and are likely disproportionately influencing the skin microenvironment compared to their genomic abundance.

Application Notes: Translating Methodology into Biological Insight

Elucidating Host-Microbe Interactions in Health and Disease

Integrated meta-omics approaches are pivotal for linking microbial communities to host physiology. In the human gut, for example, metagenomics can identify a depletion of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Metatranscriptomics can further reveal that this is accompanied by a downregulation of anti-inflammatory metabolite production, such as butyrate synthesis, providing a more mechanistic understanding of disease causation beyond correlation [6]. Similarly, the "Secrebiome"—the repertoire of secreted proteins identified via metatranscriptomics—has been used to study childhood obesity, revealing striking differences in the secretory gene expression of gut bacteria in children with obesity and metabolic syndrome [18].

The role of gut dysbiosis extends to extraintestinal sites via specialized axes, and metatranscriptomics helps delineate the active molecular players:

- Gut-Liver Axis: Transcriptomic activity of microbial enzymes involved in secondary bile acid synthesis (e.g., by Clostridium scindens) can disrupt host farnesoid X receptor (FXR) signaling in the liver, promoting steatosis and inflammation [6].

- Gut-Brain Axis: Active microbial expression of genes involved in neurotransmitter precursor synthesis (e.g., serotonin and GABA) can be quantified, with dysbiosis leading to reduced availability of these metabolites, contributing to neuropsychiatric conditions [6].

Tracking Antimicrobial Resistance in Viral Infections

A powerful application of metatranscriptomics is in surveilling the "resistome"—the collection of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs)—within active microbial communities. A 2025 study employed a non-canonical metatranscriptomics approach on samples from COVID-19 and dengue patients. This method repurposes host total RNA-seq data by computationally removing host-aligned reads to analyze the leftover microbial expression, providing an unbiased profile of transcriptionally active microbes (TAMs) and the ARGs they carry [19].

The study revealed a higher burden and diversity of ARGs in COVID-19 patients, particularly in fatal cases. Dominant ARG hosts included Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and in mortality cases, Acinetobacter baumannii. Multidrug resistance genes, especially those conferring resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., NDM, OXA, VIM carbapenemases in COVID-19), were prevalent [19]. This highlights the unintended consequence of antibiotic use in viral infections and underscores the need for active resistome surveillance to guide clinical management.

Investigating Microbial Adaptation in Extreme Environments

Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics are indispensable for studying unculturable microbes in extreme environments. A study on the hypersaline Lake Barkol used metagenomics to reconstruct 309 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), approximately 97% of which were novel at the species level, revealing extensive taxonomic novelty [20].

Metabolic reconstruction from metagenomic data identified key pathways for carbon fixation (e.g., the Calvin cycle) and sulfur cycling. Furthermore, the study pinpointed active microbial osmoadaptation strategies:

- "Salt-in" strategy: Relies on ion transport systems (Trk/Ktr potassium uptake, Na+/H+ antiporters) for intracellular homeostasis.

- "Salt-out" strategy: Involves biosynthesis of compatible solutes (ectoine, trehalose, glycine betaine) [20].

A follow-up metatranscriptomic analysis would directly show which of these strategies are being actively transcribed in response to the extreme salinity gradients between the water and sediment habitats.

Experimental Protocols

A Robust Workflow for Skin Metatranscriptomics

Studying low-biomass environments like the skin requires a optimized protocol to overcome challenges of host contamination and low RNA stability. The following workflow, developed to ensure high technical reproducibility and microbial mRNA enrichment, is detailed below [4].

Diagram 1: Skin metatranscriptomics workflow

Protocol Steps:

- Sample Collection: Use skin swabs for non-invasive sampling across body sites (e.g., scalp, cheek, forearm) [4].

- Immediate Preservation: Preserve swabs immediately in DNA/RNA Shield or similar reagent to stabilize nucleic acids and prevent degradation [4].

- Cell Lysis: Perform bead beating to ensure efficient lysis of robust microbial cell walls [4].

- RNA Purification: Use a direct-to-column TRIzol purification method for high-quality RNA extraction [4].

- rRNA Depletion: Employ custom oligonucleotides to deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA), enriching for messenger RNA (mRNA). This step is critical and achieved a 2.5–40x enrichment of non-rRNA reads in the cited study [4].

- cDNA Library Construction & Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the enriched mRNA and sequence on an Illumina NextSeq 2000 or similar platform [4].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Assess RNA quality (e.g., DV200 ≥ 76 is a good indicator) [4].

- Host Read Removal: Filter out reads that align to the host transcriptome (e.g., human genome).

- Contaminant Filtering: Use data from negative handling controls to identify and filter potential contaminant taxa from reagents or processing (the "kitome") [4].

- Taxonomic & Functional Annotation: Annotate reads using a specialized skin microbial gene catalog (e.g., the integrated Human Skin Microbial Gene Catalog, iHSMGC) for higher sensitivity than general-purpose tools [4].

Protocol for 16S rRNA Metatranscriptomics

This approach integrates taxonomic profiling with functional activity analysis from the same sample.

Diagram 2: 16S rRNA metatranscriptomics workflow

Protocol Steps:

- Sample Lysis and Co-extraction: Begin with simultaneous co-extraction of DNA and RNA using specialized kits and RNase-free consumables to minimize cross-contamination. Validate nucleic acid quality and integrity using a NanoDrop One and an Agilent Bioanalyzer [18].

- Dual-Data Generation:

- 16S rRNA Phase: Use the DNA fraction. Perform PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA V3-V4 variable region and sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq platform. Process data using QIIME2 and the DADA2 pipeline for denoising, which generates high-resolution Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). Annotate ASVs taxonomically using databases like SILVA or Greengenes [18].

- Metatranscriptomics Phase: Use the RNA fraction. Construct cDNA libraries and sequence on an Illumina HiSeq platform. Process raw reads with FastQC and Trimmomatic for quality control. Quantify transcript abundance with Salmon and identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using DESeq2. Annotate DEGs to functional pathways (e.g., KEGG) using eggNOG-mapper [18].

- Data Integration: Use tools like MetaWRAP 2.0 to integrate the taxonomic and functional datasets. Perform correlation analysis (e.g., with SparCC) to construct "microbe-gene-pathway" networks, linking specific microbes to the active functions they are performing [18].

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for metatranscriptomics

| Category | Item | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | DNA/RNA Shield | Preserves nucleic acid integrity immediately after sample collection, critical for unstable mRNA [4]. |

| RNase-free consumables | Prevents degradation of RNA during extraction and library preparation; reduces contamination rates to <0.5% [18]. | |

| Custom rRNA Depletion Oligos | Species-specific oligonucleotides for removing host and bacterial rRNA, dramatically enriching for mRNA [4]. | |

| Sequencing & Analysis | Long-Read Sequencers (ONT/PacBio) | Generate reads spanning thousands of base pairs, resolving complex genomic regions and improving metagenomic assembly [21]. |

| Skin/Gut Microbial Gene Catalogs | Specialized reference databases (e.g., iHSMGC) significantly improve annotation sensitivity for specific body sites [4]. | |

| MetaWRAP 2.0 | Bioinformatics tool for integrating multi-type microbiome data (e.g., 16S, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics) [18]. | |

| EasyNanoMeta | An integrated bioinformatics pipeline designed to address challenges in analyzing nanopore-based metagenomic data [21]. |

The journey from cataloging microbial inhabitants to understanding their real-time metabolic activity has fundamentally transformed microbial ecology. Metagenomics provides the essential blueprint of "what can they do," while metatranscriptomics dynamically reveals "what they are actually doing" in response to their environment [17] [4]. As the protocols and applications in this note demonstrate, the integration of these approaches is no longer optional for a mechanistic understanding of microbiome function. It is a necessity for advancing research in human health, from personalized therapies and AMR surveillance [19] to understanding chronic disease [6], as well as in environmental science, for uncovering novel taxa and their roles in extreme ecosystems [20]. Future progress will be driven by technological refinements in long-read sequencing [21], standardized protocols for low-biomass sites [4], and sophisticated bioinformatic tools that seamlessly merge taxonomic and functional data into a coherent biological narrative [18].

In microbial ecology, relying on a single omics technology presents a fragmented picture. Metagenomics reveals the potential functional capabilities encoded in the collective DNA of a microbiome, detailing "who is there" and "what they could potentially do" [22]. Conversely, metatranscriptomics captures the community-wide gene expression, illuminating "what functions are actively being undertaken" at the time of sampling [22] [23]. While powerful, these approaches in isolation provide an incomplete narrative. Metagenomics infers activity from genetic potential, while metatranscriptomics records expression without the genomic context for its regulation or origin. An integrated multi-omics paradigm is crucial to overcome these limitations, transforming static genetic inventories into dynamic models of microbial community behavior, function, and interaction with their hosts and environments [24]. This Application Note details the quantitative evidence, standardized protocols, and practical tools required to implement this synergistic approach, enabling researchers to fully leverage the power of integrated meta-omics.

Quantitative Evidence: The Added Value of Integration

The theoretical benefits of multi-omics integration are supported by empirical data. Studies demonstrate that integrating data from metagenomics and metatranscriptomics provides a more complex and actionable understanding of microbiome function than either method alone.

Case Study: Enhanced Metaproteomic Identification

A pivotal pilot study reanalyzed paired multi-omics datasets from human gut and marine hatchery samples to quantify the benefit of integrated data for metaproteomics. The study found that using customized protein search databases built from matched metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data significantly improved the analytical depth.

Table 1: Impact of Integrated Search Databases on Metaproteomic Analysis [24]

| Search Database Type | Method of Construction | Resulting Peptide Identifications |

|---|---|---|

| Same-Sample Multi-Omics DB | Built from assembled metagenomic & metatranscriptomic sequences from the same sample | Highest number of peptide identifications |

| Independent Sample DB | Built from genomic sequences derived from independent samples | Lower number of peptide identifications |

This study also led to the development of a dedicated workflow (MetaPUF) and the extension of the MGnify resource to visualize integrated results, establishing a robust pipeline for future integrative studies [24].

Case Study: Unraveling Host-Microbiome Immune Interactions

Metatranscriptomics has been critical in moving beyond taxonomic composition to understand functional mechanisms in host-microbiome interactions. A key example is the study of Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) knockout mice. While metagenomics could identify the taxa present, metatranscriptomic analysis revealed a crucial functional shift: the up-regulation of flagellar motor-related gene expression in the gut microbiome of TLR5KO mice compared to wild-type mice [23]. This finding illustrated that the host immune system (via TLR5) regulates microbial behavior not merely by changing community structure, but by directly influencing the expression of key bacterial virulence genes, a insight only accessible through transcript-level analysis [23].

Experimental Protocols: A Framework for Multi-Omics Integration

Implementing a successful integrated study requires meticulous planning from sample collection through computational analysis. The following protocols provide a scaffold for such investigations.

Protocol: Concurrent Sample Collection for Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics

Principle: To generate truly comparable datasets, samples for DNA and RNA extraction must be collected in a way that minimizes technical variation and accurately captures the same microbial community state [25].

Procedure:

- Sample Splitting: From a single, homogenized environmental or host sample (e.g., soil, water, gut content), immediately split the material into two aliquots.

- Simultaneous Preservation:

- For DNA (Metagenomics): Preserve one aliquot using a DNA stabilization solution (e.g., RNAlater) or by flash-freecing in liquid nitrogen, followed by storage at -80°C.

- For RNA (Metatranscriptomics): Preserve the second aliquot in a dedicated RNA stabilization reagent (e.g., TRIzol) and flash-freeze. Store at -80°C. Handle samples with RNase-free techniques to prevent degradation.

- Documentation: Record the sampling time, condition, and any relevant metadata (e.g., pH, temperature) for both aliquots identically.

Protocol: A Computational Workflow for Metatranscriptomic Analysis

This protocol, adapted for studying host-pathogen or host-microbiome interactions, outlines a dual-path analysis after total RNA extraction [26] [23].

Diagram 1: Metatranscriptomic analysis computational workflow.

Procedure:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Following rRNA depletion (a critical step to enrich for mRNA) [23] and cDNA library construction, sequence on an Illumina or equivalent platform.

- Bioinformatic Pre-processing: Perform quality control on raw reads using tools like

FastQC. Trim adapters and filter low-quality sequences [26] [27]. - Dual-Path Assembly:

- Reference-Guided Assembly: Map reads to a reference genome (if available for the host and expected microbes). This approach is precise but limited by the completeness of the reference database [26].

- De Novo Assembly: Assemble reads into transcripts without a reference using tools like

Trinity. This method is valuable for discovering novel genes or working with non-model systems [26].

- Gene Annotation and Quantification: Predict open reading frames (ORFs) and annotate genes against functional databases (e.g., KEGG, COG). Quantify gene and transcript abundance [27].

- Differential Expression and Integration: Identify statistically significant differences in gene expression between conditions. Integrate results with metagenomic data from the same sample to link active functions to their genomic hosts [24] [26].

Protocol: Building a Customized Database for Integrated Metaproteomics

This advanced protocol uses metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data to significantly improve protein identification in metaproteomic studies [24].

Procedure:

- Sequence Data Processing: Assemble metagenomic and metatranscriptomic reads from the same sample into contigs.

- Gene Calling: Perform de novo gene prediction on the assembled contigs to generate a sample-specific protein sequence database.

- Database Curation: Combine and curate the predicted protein sequences to create a comprehensive search database (search DB).

- Metaproteomic Search: Use this customized search DB to analyze mass spectrometry-based metaproteomic data, leading to a higher yield of peptide and protein identifications compared to using generic public databases [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful multi-omics research relies on a suite of wet-lab and computational resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Bioinformatics Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Wet-lab Reagent | Enriches messenger RNA (mRNA) from total RNA by removing abundant ribosomal RNA, critical for metatranscriptomics [23]. |

| DNA/RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAlater, TRIzol) | Wet-lab Reagent | Preserves nucleic acid integrity immediately upon sampling, preventing degradation and preserving the in-situ molecular profile. |

| Unison Ultralow Library Kit (Micronbrane) | Wet-lab Reagent | Streamlines library preparation for low-input DNA extracts, minimizing contamination for sensitive metagenomic studies [28]. |

| Devin Fractionation Filter (Micronbrane) | Wet-lab Tool | Reduces host-derived nucleic acids in samples from bodily fluids, increasing the sequencing depth of the microbial community [28]. |

| QIMME 2 | Bioinformatics Pipeline | A powerful, user-friendly platform for the analysis of marker-gene (e.g., 16S rRNA) metagenomic data [22]. |

| Kraken2/Bracken | Bioinformatics Tool | A suite for fast taxonomic classification of sequencing reads from metagenomic or metatranscriptomic data, providing abundance estimates [22]. |

| MGnify & PRIDE Database | Bioinformatics Resource | Public repositories for metagenomic/metatranscriptomic (MGnify) and metaproteomic (PRIDE) data, enabling data sharing, re-analysis, and integration [24]. |

| iCAMP (Phylogenetic-bin-based null model) | Bioinformatics Framework | Quantifies the relative importance of ecological processes (selection, dispersal, drift) in microbial community assembly [29]. |

| Silver diethyldithiocarbamate | Silver Diethyldithiocarbamate | Reagent for Arsenic Detection | High-purity Silver Diethyldithiocarbamate for arsenic analysis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate | Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate, CAS:14680-77-4, MF:C24H16BCl4K, MW:496.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Visualization and Interpretation Guidelines

Effectively communicating the results of complex multi-omics studies requires careful consideration of data visualization.

- For Alpha and Beta Diversity: Use box plots to compare diversity indices between groups, adding jitters to show individual data points. For beta diversity, apply ordination plots like PCoA, colored by experimental groups, to visualize overall variation [30].

- For Taxonomic and Functional Composition: Stacked bar charts are effective for showing relative abundance across groups at higher taxonomic levels. For a more detailed, sample-wise view of abundance data, heatmaps coupled with clustering are superior [30].

- For Core Microbiome Analysis: When comparing three or more groups, UpSet plots are recommended over complex Venn diagrams, as they clearly display intersections in a matrix layout [30].

- Color Selection: Adopt color palettes that are color-blind friendly (e.g.,

viridis). Maintain consistent color schemes for the same categories (e.g., phyla, treatment groups) across all figures in a publication [31] [30].

The path to a genuinely complete picture of microbial ecology no longer lies in perfecting single omics methods, but in strategically integrating them. As the quantitative data and protocols herein demonstrate, the synergistic power of metagenomics and metatranscriptomics bridges the critical gap between genetic potential and expressed function. This integrated approach is indispensable for transforming observational catalogues into mechanistic models, ultimately accelerating discovery in fields ranging from drug development [23] to environmental monitoring [29] [25]. By adopting the standardized workflows, tools, and visualization practices outlined in this Application Note, researchers can systematically unlock the full, contextualized narrative hidden within complex microbial communities.

From Sample to Insight: Technical Workflows and Translational Applications in Biomedicine

In the field of microbial ecology research, metagenomics and metatranscriptomics have revolutionized our ability to decipher the composition and function of complex microbial communities without the need for cultivation. The reliability of these advanced molecular techniques, however, is fundamentally dependent on the integrity of the technical pipeline employed—from initial sample preparation to final sequencing output. Variations in methodological choices at any stage can introduce significant biases, affecting downstream data interpretation and compromising the comparability of results across studies [32].

The selection between physical lysis methods like bead-beating and enzymatic digestion directly influences DNA yield and community representation, particularly for challenging-to-lyse microorganisms. Similarly, the choice of sequencing platform—whether short-read Illumina or long-read Nanopore technologies—carries distinct implications for genomic assembly completeness, functional annotation accuracy, and strain-level resolution. This Application Note provides a standardized framework for navigating these critical technical decisions, offering detailed protocols and comparative analyses to support researchers in generating robust, reproducible data for drug development and ecological research.

Sample Preparation: The Foundation of Reliable Metagenomics

Cell Lysis Methods: Bead-Beating vs. Enzymatic Digestion

The initial step of nucleic acid extraction is arguably the most critical in the metagenomic workflow. Efficient cell lysis is essential for obtaining a representative snapshot of the microbial community, but different bacterial cell wall structures require different lysis approaches.

Bead-Beating Protocol: This mechanical disruption method is highly effective for breaking tough cell walls. In a standardized protocol for intestinal microbiota analysis, researchers used repeated bead beating with a mini-bead beater (Biospec Products) on approximately 200 mg of sample [33]. The protocol involves:

- Homogenizing samples in sterile potassium phosphate buffer containing 15% glycerol.

- Using a bead beater with appropriate bead sizes (typically a mixture of 0.1mm and 0.5mm diameter beads) to ensure comprehensive disruption of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

- Critical parameter optimization: Homogenization time significantly impacts sample diversity, with research recommending shorter homogenization times (10 minutes) for better reflection of the gram-positive/gram-negative ratio and reduced beta-diversity heterogeneity [32].

Enzymatic Lysis Protocol: This alternative method utilizes enzyme cocktails to degrade specific cell wall components:

- Lysozyme targets peptidoglycan layers in Gram-positive bacteria.

- Mutanolysin provides additional activity against complex peptidoglycan structures.

- Proteinase K digests proteins and aids in breaking down cellular matrices.

- Typical incubation: 1-2 hours at 37°C with occasional mixing.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cell Lysis Methods for Metagenomic DNA Extraction

| Parameter | Bead-Beating | Enzymatic Digestion |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency for Gram-positive bacteria | High | Moderate to Low |

| Efficiency for Gram-negative bacteria | High | High |

| DNA fragment size | Shorter fragments (requires optimization) | Longer fragments |

| Risk of contamination | Low (closed systems available) | Moderate (multiple reagent additions) |

| Processing time | Fast (minutes) | Slow (hours) |

| Cost per sample | Moderate | Low to Moderate |

| Reproducibility | High with standardized timing | High with standardized enzyme lots |

Impact of Homogenization on Community Representation

The duration of homogenization significantly affects the observed microbial community composition. Studies have demonstrated that shorter homogenization times (10 minutes) provide more accurate representations of the gram-positive/gram-negative ratio in complex samples like stool, while longer homogenization introduces bias and increases heterogeneity in beta-diversity measurements [32]. This highlights the necessity of standardizing this parameter within and across studies to ensure comparability.

Sequencing Platform Selection: Illumina vs. Nanopore

The choice of sequencing platform dictates the scope and resolution of metagenomic analysis, with short-read and long-read technologies offering complementary advantages.

Illumina Sequencing (Short-Read Technology):

- Technology basis: Sequencing by synthesis with reversible dye-terminators

- Read length: Typically 2×150 bp to 2×300 bp paired-end reads [34]

- Error profile: Low error rate (<0.1%), predominantly substitution errors

- Ideal applications: 16S rRNA gene sequencing, shotgun metagenomics for high-resolution community profiling, and projects requiring high accuracy for single-nucleotide variant calling

Nanopore Sequencing (Long-Read Technology):

- Technology basis: Measurement of changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores

- Read length: Averages 10 kb, with reads potentially exceeding 100 kb [35]

- Error profile: Higher error rate (1-5%), predominantly indels, but improving with chemistry advances

- Ideal applications: Metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) reconstruction, strain-level resolution, structural variant detection, and real-time analysis in field settings

Performance Comparison for Metagenomic Applications

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Specifications for Metagenomic Applications

| Specification | Illumina MiSeq | Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000 | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Output | 15 Gb | 540 Gb | Dependent on flow cell (up to hundreds of Gb) |

| Run Time | 4-55 hours | ~8-44 hours | Variable (hours to days) |

| Read Length | 2 × 300 bp | 2 × 300 bp | Average 10 kb+ |

| Key Metagenomic Strengths | 16S rRNA sequencing, targeted gene sequencing | High-throughput shotgun metagenomics | Superior MAG recovery, strain-level resolution |

| Error Rate | <0.1% | <0.1% | 1-5% (improving with new chemistries) |

| Cost Considerations | ~$10/sample for 16S (96-plex) [36] | Higher throughput, lower cost per Gb | Lower initial instrument investment |

Nanopore sequencing demonstrates particular advantages for complex microbiome analysis, serving as a standalone platform that provides superior metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) recovery and strain-level resolution from complex microbiomes [37]. The long reads generated by Nanopore technology enable more complete genome reconstruction by spanning repetitive regions that challenge short-read technologies.

Integrated Workflow: From Sample to Analysis

Complete Experimental Pipeline

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated technical pipeline from sample preparation through data analysis, highlighting critical decision points and their implications for result interpretation:

Diagram Title: Integrated Metagenomic Analysis Workflow

Library Preparation Considerations

Library preparation methodology represents another potential source of bias in metagenomic studies:

- Tagmentation-based methods (e.g., Illumina Nextera) offer rapid processing and reduced hands-on time but may introduce sequence preference biases [32].

- PCR-free protocols (e.g., KAPA Hyper Prep, TruSeq DNA PCR-free) minimize amplification biases but require higher input DNA, which can be challenging for low-biomass samples [38].

- Platform-specific kits are optimized for their respective technologies, with Nanopore offering rapid sequencing library preparation (often under 30 minutes) compared to more lengthy Illumina protocols.

Studies have demonstrated that the choice of library preparation kit significantly influences the reproducibility of results, with tagmentation-based methods generally providing the most consistent results across replicates [32].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications in Metagenomic Workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | Qiagen | DNA extraction from complex samples | Recommended in Human Microbiome Project; effective for soil and stool [32] |

| KAPA Hyper Prep Kit | Kapa Biosystems | PCR-free library preparation | Maintains representation of original community; requires sufficient DNA input [32] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Illumina | Tagmentation-based library prep | Fast protocol; potential for sequence preference bias [32] |

| TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Illumina | High-quality library preparation | For projects requiring maximum sequence accuracy [33] |

| Ligation Sequencing Kit | Oxford Nanopore | Library prep for Nanopore | Maintains long read lengths; rapid preparation [37] |

Navigating the technical pipeline from sample preparation to sequencing platform selection requires careful consideration of research objectives, sample types, and analytical priorities. Based on current methodological evaluations, the following recommendations emerge:

- Standardize homogenization protocols using shorter durations (∼10 minutes) for more accurate community representation [32].

- Implement bead-beating for comprehensive lysis of diverse community members, particularly when Gram-positive bacteria are of interest.

- Select sequencing platforms based on study goals: Illumina for high-accuracy community profiling, Nanopore for superior genome reconstruction and strain-level resolution [37] [39].

- Maintain consistency in library preparation methods within studies to enhance reproducibility and comparability.

The rapid evolution of both sequencing technologies and computational tools necessitates ongoing reassessment of these protocols. However, the fundamental principle of methodological standardization remains critical for advancing our understanding of microbial ecology through metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches.

Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics have revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling culture-independent analysis of complex microbial communities. These approaches provide unprecedented insights into the genomic potential and transcriptional activities of microorganisms directly from their natural environments, from human guts to global ecosystems like oceans and soil [40]. The bioinformatic processing of data generated by these high-throughput technologies is a critical pillar supporting this research. This guide details the essential computational steps—quality control, taxonomic profiling, assembly, and binning—framed within the context of robust, reproducible microbial ecology research. The standardization of these workflows is paramount for generating biologically meaningful and comparable data, ultimately driving discoveries in ecosystem dynamics, host-microbe interactions, and biotechnology [41] [40].

The analysis of metagenomic data follows a structured pipeline designed to transform raw sequencing reads into biological insights regarding community composition and function. The workflow can be broadly divided into two computational strategies: read-based profiling and assembly-based methods [42]. The following diagram illustrates the standard stages of a metagenomic analysis, highlighting the points where these two strategies diverge and converge.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Quality Control and Read Preprocessing

The initial and crucial step in any metagenomic analysis is ensuring data quality. This process removes technical artifacts and prepares reads for downstream analysis.

Detailed Protocol: Quality Control with Trimmomatic and FastQC

This protocol is adapted from established metagenomic pipelines like Metabiome and metaTP [43] [44].

- Input: Raw paired-end or single-end sequencing reads in FASTQ format.

- Quality Assessment:

- Run FastQC on all raw FASTQ files to assess base quality scores, sequence length distribution, adapter contamination, and GC content.

- Use MultiQC to aggregate and visualize FastQC reports from multiple samples into a single summary [43].

- Quality Trimming and Adapter Removal:

- Execute Trimmomatic in paired-end mode with the following parameters [40] [43]:

ILLUMINACLIP:Path to adapter sequences (e.g.,TruSeq3-PE-2.fa), with a mismatch threshold of 2 and a palindrome clip threshold of 30.SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20to perform a sliding window trimming, cutting when the average quality per base drops below 20 within a 4-base window.LEADING:20to remove low-quality bases from the start of the read.TRAILING:20to remove low-quality bases from the end of the read.MINLEN:50to discard reads shorter than 50 base pairs after trimming.

- Execute Trimmomatic in paired-end mode with the following parameters [40] [43]:

- Host DNA Depletion:

- Output: High-quality, decontaminated paired-end and single-end reads for taxonomic profiling or assembly.

Taxonomic Profiling

This step identifies the microorganisms present in a sample and estimates their relative abundance. The two primary approaches are read-based (marker-gene or k-mer based) and assembly-based.

Detailed Protocol: Read-based Profiling with MetaPhlAn3 and Kraken2/Bracken

This protocol leverages the Metabiome pipeline for marker-gene and k-mer-based classification [43].

- Input: High-quality, decontaminated reads from the previous step.

- Marker-Gene Based Profiling with MetaPhlAn3:

- Run MetaPhlAn3 with a custom or default database (e.g.,

mpa_v30_CHOCOPhlAn_201901). - Use flags like

--ignore_eukaryotesand--ignore_archaeato focus on bacterial and viral communities if desired. - The output is a table of taxon relative abundances across samples (

merged_abundance_table.txt).

- Run MetaPhlAn3 with a custom or default database (e.g.,

- K-mer Based Profiling with Kraken2/Bracken:

- Database Preparation: Download a pre-formatted Kraken2 database (e.g., Standard, MiniKraken, or a specialized database like the Viral genome database).

- Classification: Run Kraken2 against the database. Kraken2 breaks reads into k-mers and matches them to a reference library for rapid taxonomy assignment [42].

- Abundance Estimation: Use Bracken (Bayesian Reestimation of Abundance with KrakEN) to re-estimate species- or genus-level abundances from the Kraken2 output, correcting for ambiguous mappings [42].

- Visualization:

- Generate Krona pie charts for interactive visualization of the taxonomic composition from Kraken2 output using the

kronatool [43].

- Generate Krona pie charts for interactive visualization of the taxonomic composition from Kraken2 output using the

- Output: Tables of taxonomic identity and relative abundance for each sample, along with visualizations.

Metagenomic Assembly and Binning

For studies aiming to reconstruct genomes or genes, de novo assembly and binning are essential. This is often referred to as the Assembly-Binning-Method and is critical for achieving high taxonomic resolution and accurate quantitative abundance estimation [42].

Detailed Protocol: MAG Reconstruction with metaSPAdes/MEGAHIT and MetaBAT2

This protocol is synthesized from multiple sources detailing MAG reconstruction workflows [41] [40] [45].

- Input: High-quality, decontaminated reads.

- De Novo Assembly:

- Option 1 (Short-reads): Use MEGAHIT, which employs succinct de Bruijn graphs and is memory-efficient. A dynamic k-mer range (e.g., 21-127) is recommended to resolve high-coverage regions [40].

- Option 2 (Short-reads): Use metaSPAdes for high-quality metagenomic assemblies, especially with complex communities.

- Option 3 (Long-reads/Hybrid): For PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore reads, use assemblers like hifiasm-meta or Flye. Hybrid assembly (combining short and long reads) using tools like OPERA-MS can significantly improve contiguity, boosting N50 contig length by 40% or more [40] [45].

- Binning:

- Contig Coverage Profiling: Map the quality-filtered reads back to the assembled contigs using Bowtie2 or BWA. Calculate coverage depth (average number of reads mapping to a contig) for each sample in a multi-sample dataset.

- Binning Execution: Run MetaBAT2, which integrates sequence composition (tetranucleotide frequency), coverage abundance across samples, and probabilistic models to cluster contigs into putative genomes (bins) [40] [45]. SemiBin2 is another modern binner that can be used.

- Binning Refinement: Use DASTool to consolidate bins from multiple binning runs (e.g., from MetaBAT2 and SemiBin2), creating a non-redundant set of high-quality bins [45].

- Quality Assessment of MAGs:

- Assess the completeness and contamination of the refined bins using CheckM or CheckM2, which rely on the presence of single-copy marker genes [45].

- Classify MAGs according to the MIMAG standards [41]:

- High-quality draft (HQ): ≥90% completeness, ≤5% contamination, presence of rRNA genes and tRNAs.

- Medium-quality draft (MQ): ≥50% completeness, ≤10% contamination.

- Output: A collection of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) with quality estimates, ready for taxonomic annotation and functional analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Databases

Successful bioinformatic analysis relies on a suite of software tools and reference databases. The table below summarizes key resources for each stage of the workflow.

Table 1: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Metagenomic Analysis

| Analysis Stage | Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC [44] [43] | Quality assessment of raw reads | Generates a comprehensive HTML report |

| Trimmomatic [44] [40] | Read trimming & adapter removal | Flexible parameters for sliding window, leading, and trailing | |

| Host Depletion | Bowtie2 [40] [43] | Alignment of reads to a host genome | Efficiently separates host and non-host reads |

| Taxonomic Profiling | MetaPhlAn3 [43] | Marker-gene based profiling | Uses unique clade-specific markers for high taxonomic resolution |

| Kraken2/Bracken [42] [43] | k-mer based classification & abundance estimation | Extremely fast classification; Bracken refines abundance estimates | |

| Assembly | MEGAHIT [44] [40] | De novo short-read assembly | Memory-efficient, designed for metagenomics |

| metaSPAdes [40] [43] | De novo short-read assembly | Creates high-quality assemblies from complex metagenomes | |

| hifiasm-meta [45] | De novo long-read (HiFi) assembly | Specialized for accurate long reads to generate contiguous MAGs | |

| Binning | MetaBAT2 [40] [45] | Binning of contigs into MAGs | Uses sequence composition and coverage |

| DASTool [40] [45] | Binning refinement and dereplication | Consolidates bins from multiple tools to yield a superior set | |

| MAG Quality | CheckM2 [45] | Assesses MAG quality (completeness/contamination) | Fast and accurate estimation using machine learning |

| Taxonomy | GTDB [41] [40] | Genome Taxonomy Database | Standardized bacterial and archaeal taxonomy based on genomics |

| Functional Annotation | eggNOG-mapper [44] [40] | Functional annotation of genes | Assigns KEGG, COG, and Gene Ontology terms |

| Normetanephrine hydrochloride | Normetanephrine Hydrochloride|High-Qurity Reference Standard | Normetanephrine hydrochloride for research. A key catecholamine metabolite for studying neuroendocrine tumors. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 4,7-Dibromo-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole | 4,7-Dibromo-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole|High-Purity Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The performance of different methodological choices can be quantitatively evaluated. The following table compares two main taxonomic profiling approaches based on a mock community study.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Shotgun Sequencing Analysis Methods on a 19-Species Mock Community [42]

| Analysis Method | Sensitivity | Precision | Taxonomic Resolution | Quantitative Correlation with Expected Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly-Binning-Method | Comparable to rpoB metabarcoding | Comparable to rpoB metabarcoding | High (species-level identification achieved) | High (consistently higher correlation and lower dissimilarity) |

| k-mer Approach (Kraken2) | Lower (high false negatives) | Lower | Variable | Not reported as superior to Assembly-Binning |

Furthermore, the choice of sequencing technology directly impacts assembly quality. Long-read sequencing can produce dramatically more complete metagenome-assembled genomes, as demonstrated by a service provider's results.

Table 3: Performance of Long-Read Metagenomic Sequencing on a Fecal Sample [45]

| Metric | Result |

|---|---|

| Sequencing Platform | PacBio Sequel IIe |

| Number of HiFi Reads | 1,792,146 reads |

| Mean Read Length | 10,318 bp |

| Mean Read Quality (Q-score) | > Q20 ( >99% accuracy) |

| Number of High-quality MAGs Recovered | 100 MAGs |

The bioinformatic processing of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data is a foundational activity in modern microbial ecology. This guide has detailed the core protocols for quality control, taxonomic profiling, assembly, and binning, providing a roadmap for generating robust and reproducible results. As the field evolves, the integration of long-read sequencing, hybrid assembly strategies, and automated, workflow-managed pipelines like those built on Snakemake and Nextflow will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex interplay within microbial communities [41] [44]. Adherence to these standardized methodologies ensures that researchers can reliably translate vast amounts of sequencing data into meaningful ecological insights, ultimately advancing our understanding of the microbial world.

Application Notes: Clinical Signatures in Patient Care

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) and metatranscriptomics are revolutionizing clinical microbiology by providing unbiased, culture-independent tools for comprehensive pathogen detection. These approaches allow for the simultaneous identification of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, along with their functional characteristics, directly from clinical specimens [46] [47]. By sequencing all nucleic acids in a sample, these methods uncover clinical signatures—distinct patterns of microbial presence, gene expression, and functional activity—that provide critical diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic insights.

The clinical utility of these signatures is particularly evident in complex diagnostic scenarios. The tables below summarize key performance data and clinical applications of mNGS and metatranscriptomics across various medical conditions.

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of mNGS and Metatranscriptomics in Clinical Studies

| Condition | Sample Type | Technology | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Pneumonia | Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) | mNGS | Sensitivity: 94.74%; Positivity Rate: 93.5% (vs. 55.7% with CMT) | [48] |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) Infection | Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | mNGS | Increased diagnostic yield by 6.4%; identified rare pathogens (e.g., Leptospira santarosai) | [49] [50] |

| Pediatric Acute Sinusitis | Nasopharyngeal Swab | Metatranscriptomics | Sensitivity: 87% (bacteria), 86% (viruses); Specificity: 81% (bacteria), 92% (viruses) | [51] |

| Bone and Joint Infections | Tissue/Aspirate | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Improved diagnostic yield by ~18% over culture alone | [49] |

| Sepsis | Blood | Shotgun Metagenomics | Enabled pathogen identification up to 30 hours earlier than culture | [49] |

Table 2: Key Clinical Applications of Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Analyses

| Application Area | Clinical Utility | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|