Microbial Adaptation to Global Change: Mechanisms, Models, and Biomedical Implications

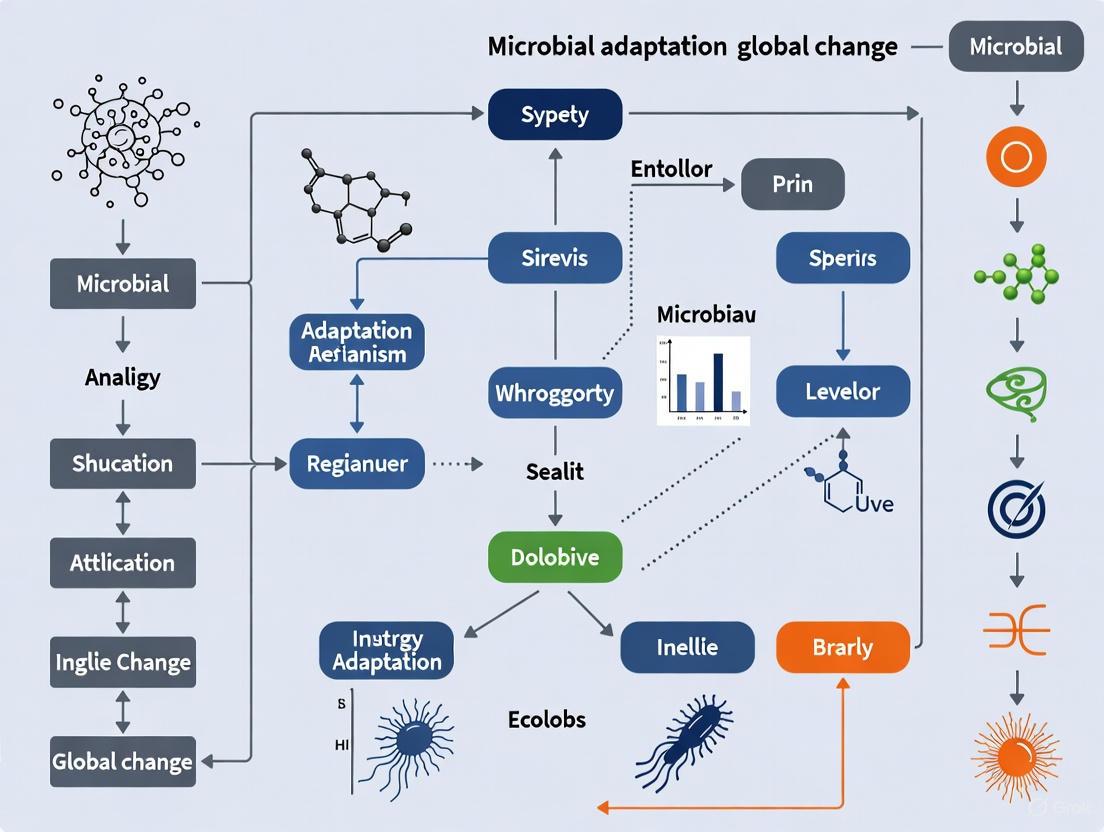

This article synthesizes current research on the mechanisms by which microorganisms adapt to rapid global environmental change, a critical frontier in microbial ecology and evolution.

Microbial Adaptation to Global Change: Mechanisms, Models, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the mechanisms by which microorganisms adapt to rapid global environmental change, a critical frontier in microbial ecology and evolution. We explore the foundational genetic and eco-evolutionary processes—from horizontal gene transfer to trait optimization—that underpin microbial resilience. The content details methodological advances in tracking and engineering these adaptations, addresses challenges in scaling findings from lab to ecosystem, and validates models against real-world data from unique environments like the International Space Station and low-permeability soils. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review highlights the profound implications of microbial adaptation for climate feedbacks, pathogen emergence, and the development of microbiome-based therapies, providing a comprehensive framework for future biomedical and clinical research.

The Genetic and Eco-Evolutionary Basis of Microbial Adaptation

Genetic diversification is the cornerstone of microbial adaptation, enabling rapid responses to environmental stressors such as antibiotics, host immune systems, and changing ecological niches. In prokaryotes, this process is driven primarily by three core mechanisms: horizontal gene transfer (HGT), gene duplication, and the activity of insertion sequences (ISs). These mechanisms operate synergistically to generate genetic diversity, expand metabolic capabilities, and facilitate evolutionary innovation within microbial populations. Within the context of global change mechanisms research, understanding these fundamental processes provides critical insights into how microorganisms adapt to anthropogenic pressures, including antibiotic use, climate change, and environmental pollution.

HGT allows for the direct acquisition of novel genes from distantly related organisms, effectively bypassing the constraints of vertical inheritance. Gene duplication, including segmental duplications and whole-plasmid multimerization, creates redundant genetic material that can evolve new functions or provide dosage benefits under selective pressure. Insertion sequences, as the simplest autonomous transposable elements, act as intrinsic mutagens and facilitate genomic rearrangements, gene inactivation, and the mobilization of genetic cargo. The interplay between these mechanisms creates a dynamic genomic landscape where mobile genetic elements (MGEs) serve as both drivers and substrates of evolutionary change.

This technical review synthesizes current research on these core mechanisms, with emphasis on their integrated roles in microbial adaptation. We present quantitative analyses of duplication events, detailed experimental methodologies for studying these processes, visualization of key mechanisms, and essential tools for researchers investigating microbial evolution in the context of global change.

Quantitative Landscape of Genetic Diversification

Recent genomic studies have provided substantial quantitative data on the prevalence and impact of gene duplication and HGT in microbial populations. These findings highlight the significance of these mechanisms in bacterial adaptation, particularly under antibiotic selection pressure.

Table 1: Prevalence of Duplicated Genes in Bacterial Genomes

| Study Focus | Dataset | Key Finding | Statistical Result | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segmental Duplications in Plasmids | 6,784 enterobacterial plasmids | Plasmids containing duplicated regions | 65% (4,409 plasmids) | MGEs drive segmental duplications, amplifying cargo genes including ARGs [1] |

| Antibiotic Resistance Gene Duplications | 24,102 complete bacterial genomes | Enrichment in human & livestock isolates | Highly enriched (p<0.05) | Direct correlation between antibiotic use and ARG duplication [2] |

| Clinical Isolate ARG Duplications | 321 antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates | Further enrichment beyond general isolates | Further enriched (p<0.05) | Strong selection for duplicated ARGs in treatment contexts [2] |

| Plasmid Self-Similarity | Enterobacterial plasmids | Putative duplication events via self-BLASTn | 74% (5,043 plasmids) | Widespread occurrence of duplication events in plasmids [1] |

Table 2: Experimental Evolution Results on Gene Duplication under Antibiotic Selection

| Experimental Condition | Genetic Background | Selection Agent | Observation | Time to Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active transposase + plasmid | E. coli DH5α | Tetracycline (50 μg/mL) | Multiple tetA transpositions to chromosome and plasmid | 9 days [2] |

| Active transposase ± plasmid | E. coli MG1655 (wild-type K-12) | Tetracycline | tetA duplications in all replicates | 1 day (~10 generations) [2] |

| Transposase-free controls | E. coli MG1655 | Tetracycline | No tetA duplications; acrAB efflux pump amplifications | 1 day (~10 generations) [2] |

| Multiple ARG transposons | E. coli MG1655 | Spectinomycin, Kanamycin, Carbenicillin, Chloramphenicol | ARG duplications in 8/8 populations across all antibiotics | 1 day [2] |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that gene duplication represents a widespread adaptive strategy in prokaryotes, contrary to historical assumptions that positioned HGT as the predominant mechanism. The enrichment of duplicated antibiotic resistance genes in clinical and livestock-associated isolates directly implicates anthropogenic selection pressures in shaping microbial genomes. Furthermore, the experimental data confirm that duplication can emerge rapidly under appropriate selective conditions, highlighting its role as a first-line response to environmental challenges.

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Mechanisms and Impacts

HGT as a Driver of Microbial Adaptation

Horizontal gene transfer enables the rapid acquisition of adaptive traits across taxonomic boundaries, fundamentally altering the evolutionary trajectory of microbial populations. Unlike vertical gene transfer, HGT operates through mechanisms that bypass reproductive boundaries, allowing for the direct exchange of genetic material between distantly related organisms. This process is particularly significant for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factors, and metabolic pathways across microbial communities [3].

The evolutionary impact of HGT extends beyond the simple acquisition of novel genes. Mathematical modeling reveals that HGT can significantly alter the stability landscape of microbial communities, promoting multistability where multiple community compositions can persist under identical environmental conditions [4]. This multistability has profound implications for microbiome function and resilience, particularly in host-associated environments where regime shifts between alternative stable states can trigger transitions between health and disease states [4].

Interplay Between HGT and Mobile Genetic Elements

Mobile genetic elements, including plasmids, transposons, and integrons, serve as primary vehicles for HGT in prokaryotic systems. These elements facilitate the mobilization, packaging, and integration of genetic cargo between microbial chromosomes and extrachromosomal elements. The recent discovery of widespread horizontal transposable element transfer (HTT) in diverse eukaryotic lineages, including vertebrates, demonstrates that this mechanism extends beyond prokaryotic domains [5].

Helitrons, a distinct class of eukaryotic rolling-circle transposons, exemplify the profound impact of HTT on genome evolution. Recent evidence identifies multiple recent HTT events involving Helitron elements across divergent vertebrate lineages, including reptiles, ray-finned fishes, and amphibians, with invasion times estimated between 0.58 and 10.74 million years ago [5]. These elements significantly reshape host genomes through gene capture and exon shuffling, particularly affecting genes involved in early embryonic development in systems such as Xenopus laevis [5].

Diagram 1: Horizontal gene transfer mechanisms, vectors, and adaptive outcomes. HGT operates through three primary mechanisms (conjugation, transformation, transduction) facilitated by various mobile genetic elements, leading to diverse adaptive outcomes.

Gene Duplication: From Segmental Duplications to Transient Amplifications

Detection and Characterization of Segmental Duplications

Segmental duplications represent a class of genetic duplication events that span contiguous genomic regions, often encompassing multiple genes or functional elements. The detection of these elements has been historically challenging due to sequence divergence following duplication events, which fragments continuous sequence similarity and complicates reconstruction using standard alignment methods [1].

The SegMantX algorithm addresses this limitation through a novel local alignment chaining approach that joins consecutive local alignment hits into continuous segments despite heterogeneous sequence divergence [1]. The algorithm employs a scaled gap metric (Di,j) to identify and bridge fragmented alignments:

Di,j = (li + lj)/gi,j

where li and lj represent the lengths of alignment hits i and j, and gi,j denotes the absolute gap length separating them in nucleotides. The method applies thresholds for maximum gap length (m) and maximum scaled gap (s) to control chaining parameters, effectively distinguishing true segmental duplications from spurious alignments between widely spaced repetitive elements [1].

Application of SegMantX to enterobacterial plasmids reveals that approximately 65% contain duplicated regions, with a strong enrichment for mobile genetic elements and noncoding sequences. These findings position MGEs as primary drivers of segmental duplications in plasmid evolution, facilitating the amplification of cargo genes including antibiotic resistance determinants [1].

Experimental Demonstration of Selection for Gene Duplications

Controlled evolution experiments provide direct evidence for the role of antibiotic selection in driving gene duplications through MGE transposition. These studies employ defined genetic systems to quantify the dynamics of duplication emergence under selective pressure.

Table 3: Key Resources for Studying Gene Duplication and HGT

| Resource/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SegMantX | Software algorithm | Detection of diverged segmental duplications via local alignment chaining | Reconstruction of segmental duplications in prokaryotic genomes [1] |

| PGAP2 | Software toolkit | Pan-genome analysis with ortholog/paralog identification | Large-scale genomic analysis of genetic diversity [6] |

| Tn5 Transposase | Experimental reagent | Mobilization of engineered mini-transposons | Experimental evolution studies of gene duplication [2] |

| Mini-transposon Constructs | Molecular genetic tool | Delivery of antibiotic resistance genes for duplication studies | Tracking transposition events and duplication dynamics [2] |

| Long-read Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) | Genomics technology | Resolution of repetitive regions and duplicated genes | Accurate characterization of duplication events in genomes [2] |

The experimental protocol for demonstrating selection-driven gene duplications typically involves:

Strain Construction: Engineering E. coli strains harboring a minimal transposon containing an antibiotic resistance gene (e.g., tetA conferring tetracycline resistance) flanked by 19-bp terminal repeats, with transposase provided in trans [2].

Evolution Experiment: Propagating replicate populations for defined periods (1-9 days, approximately 10-90 generations) under antibiotic selection at concentrations where duplication provides a fitness benefit (e.g., 50 μg/mL tetracycline) [2].

Control Conditions: Maintaining parallel populations without antibiotic selection to distinguish selection-specific effects from spontaneous mutation events [2].

Genomic Analysis: Sequencing populations using long-read technologies to resolve duplication structures and track their frequencies across replicates and timepoints [2].

These experiments consistently demonstrate that antibiotic selection drives the rapid emergence of duplicated resistance genes, while control populations maintained without selection show no such duplications [2]. The dependence on active transposase confirms the central role of MGEs in facilitating these adaptive genetic rearrangements.

Insertion Sequences as Catalysts of Genomic Rearrangement

Insertion sequences represent the simplest autonomous transposable elements in prokaryotic genomes, typically encoding only the functions necessary for their own transposition. Despite their structural simplicity, IS elements function as powerful intrinsic mutagens, catalyzing a diverse array of genomic rearrangements including insertions, deletions, inversions, and larger-scale genomic reorganizations.

The mutagenic potential of IS elements stems from their ability to: (1) disrupt coding sequences and regulatory regions upon insertion, (2) mediate ectopic homologous recombination between copies located at different genomic positions, and (3) serve as portable regions of homology that facilitate secondary genetic rearrangements. These activities collectively enhance genomic plasticity and create subpopulations with diverse genotypes upon which selection can act.

In plasmid genomes, IS elements are frequently associated with duplicated regions, particularly those involving mobile genetic elements and antibiotic resistance genes [1]. This association reflects the dual role of IS elements as both substrates and catalysts of duplication events—they can be duplicated themselves while simultaneously facilitating the duplication of adjacent genetic cargo through transposition and recombination mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Mutagenic mechanisms and genomic outcomes of insertion sequence activity. IS elements function through multiple mutagenic mechanisms that generate diverse genomic outcomes and associate specifically with plasmid duplication events.

Integrated Framework of Genetic Diversification

The three core mechanisms of genetic diversification—HGT, gene duplication, and insertion sequence activity—do not operate in isolation but rather function as an integrated system that accelerates microbial adaptation. This integrative framework positions MGEs as central players that connect and potentiate the different mechanisms.

HGT introduces novel genetic material into genomes, including new IS elements and potential substrates for duplication events. Gene duplication amplifies beneficial genes, including those acquired via HGT, to enhance gene dosage under strong selection. Insertion sequences facilitate both processes by enabling the intragenomic mobility that leads to duplications and by serving as components of the composite MGEs that mediate HGT. This creates a feedback cycle where each mechanism reinforces the others, generating combinatorial diversity that far exceeds what any single mechanism could produce independently.

Mathematical modeling of microbial populations undergoing HGT reveals that these interactions can produce nonrandom MGE associations that either accelerate or constrain microbial adaptation depending on evolutionary conflicts between MGEs and their bacterial hosts [3]. The net effect of these interactions shapes the evolutionary potential of bacterial populations facing environmental challenges, including antibiotic treatment and other anthropogenic pressures [3].

The integrated action of these mechanisms is particularly evident in the context of antibiotic resistance. Clinical isolates exhibit significant enrichment of duplicated antibiotic resistance genes, with these duplicated genes more likely to be associated with MGEs than single-copy resistance genes [2]. This pattern reflects the synergistic action of all three mechanisms: HGT disseminates resistance genes across strains and species, duplication amplifies their dosage to enhance resistance levels, and IS activity facilitates the genetic rearrangements that enable both processes.

Methodologies for Investigating Genetic Diversification

Computational Approaches for Detecting Duplications and HGT

Advanced computational tools are essential for characterizing the extent and impact of genetic diversification mechanisms in microbial genomes:

SegMantX provides a specialized framework for reconstructing diverged segmental duplications that evade detection by standard alignment methods. The workflow involves: (1) self-similarity search using BLASTn or similar tools, (2) local alignment chaining using the scaled gap metric, (3) segment reconstruction, and (4) annotation of duplicated regions [1]. This approach significantly outperforms standard methods in detecting duplications with heterogeneous sequence divergence.

PGAP2 offers comprehensive pan-genome analysis capabilities specifically designed for large-scale genomic datasets. The toolkit employs a dual-level regional restriction strategy that combines gene identity networks with synteny information to accurately identify orthologous and paralogous genes [6]. Key steps include: (1) data quality control and representative genome selection, (2) ortholog inference through fine-grained feature analysis, (3) paralog identification, and (4) pan-genome profiling and visualization [6].

Long-read sequencing technologies (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) are critical for resolving duplicated regions and repetitive sequences that complicate assembly with short-read technologies. These methods enable accurate characterization of duplication structures and copy number variation in bacterial isolates and metagenomic samples [2].

Experimental Evolution Protocols

Controlled evolution experiments represent a powerful approach for directly observing the dynamics of genetic diversification under defined selective pressures:

Gene Duplication under Antibiotic Selection:

- Strain Construction: Engineer strains with defined mobile genetic elements, such as mini-transposons containing antibiotic resistance genes with identifiable terminal repeats [2].

- Evolution Conditions: Propagate replicate populations under relevant antibiotic concentrations, with parallel control populations maintained without selection [2].

- Time-Series Sampling: Collect population samples at regular intervals to track the emergence and dynamics of genetic variants [2].

- Variant Characterization: Use long-read sequencing to resolve structural variants and quantify their frequencies within populations [2].

HGT Dynamics in Community Contexts:

- Donor-Recipient Systems: Establish co-cultures with defined donor and recipient strains marked with complementary selection markers [4].

- Plasmid Transfer Monitoring: Track conjugative transfer of marked plasmids through selective plating and PCR confirmation [4].

- Community Dynamics Analysis: Apply mathematical modeling to quantify transfer rates and fitness effects of acquired elements [4].

Diagram 3: Experimental workflow for studying gene duplication under antibiotic selection. The protocol involves strain preparation with engineered transposons, experimental evolution under selection with appropriate controls, and genomic analysis to characterize emergent duplications.

Horizontal gene transfer, gene duplication, and insertion sequence activity represent three fundamental mechanisms that drive genetic diversification in microbial populations. While each mechanism operates through distinct molecular processes, their functional integration creates a synergistic system that accelerates adaptive evolution in response to environmental challenges, including those associated with global change.

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that gene duplication represents a widespread adaptive strategy in prokaryotes, contrary to historical assumptions that positioned HGT as the predominant mechanism. The enrichment of duplicated antibiotic resistance genes in clinical and livestock-associated isolates directly implicates anthropogenic selection pressures in shaping microbial genomes. Furthermore, the experimental data confirm that duplication can emerge rapidly under appropriate selective conditions, highlighting its role as a first-line response to environmental challenges.

Methodological advances in computational analysis and experimental evolution have provided unprecedented insights into the dynamics of these processes. Tools such as SegMantX and PGAP2 enable comprehensive characterization of duplication events and HGT patterns in genomic datasets, while controlled evolution experiments directly capture the real-time dynamics of adaptation through genetic diversification. These approaches collectively provide a powerful toolkit for investigating microbial adaptation within the context of global change mechanisms research.

Understanding these core mechanisms of genetic diversification has profound implications for addressing pressing challenges in antimicrobial resistance, microbiome engineering, and environmental adaptation. By elucidating the fundamental processes that enable microbial populations to explore genetic novelty and rapidly adapt to novel selective pressures, this research provides critical insights into the evolutionary dynamics that shape microbial responses to anthropogenic environmental change.

Eco-evolutionary feedback loops describe the process whereby ecological changes drive evolutionary adaptations, which in turn alter the ecological context, creating a reciprocal dynamic that occurs over contemporary, observable timescales [7]. In microbial systems, these feedbacks are particularly potent due to rapid generation times and large population sizes. Understanding these mechanisms is critical within the broader thesis of microbial adaptation to global change, as they determine how ecosystems will respond to, and potentially mitigate, anthropogenic environmental shifts [8]. These dynamics span scales, from molecular and physiological traits to ecosystem-level functions, and are foundational for predicting ecosystem resilience and guiding sustainable management strategies [8]. This review synthesizes the theoretical frameworks, experimental evidence, and methodological protocols essential for researching how trait optimization and community-level coevolution interact in a rapidly changing world.

Theoretical Foundations: From Adaptive Dynamics to Evolutionary Games

The study of eco-evolutionary feedbacks is underpinned by robust theoretical frameworks that integrate ecology and evolution.

The Adaptive Dynamics Framework

Adaptive dynamics theory was specifically devised to account for feedbacks between ecological and evolutionary processes [7]. The core of this framework is the eco-evolutionary feedback loop, which involves three key ingredients:

- Individual Phenotype: Described by adaptive, quantitative traits of interest.

- Ecological Dynamics: A model relating individual traits to population, community, or ecosystem properties.

- Trait Inheritance: A model for how traits are passed to offspring, including the potential for new mutations [7].

This framework predicts that successive trait substitutions driven by eco-evolutionary feedbacks can sometimes erode population size or growth rate, leading to evolutionary suicide or populations becoming trapped in maladaptive states, known as evolutionary trapping [7]. These outcomes are common in models where smooth trait variation causes catastrophic changes in ecological state.

Evolutionary Game Theory in Microbial Systems

Evolutionary game theory provides a powerful lens for understanding microbial interactions, particularly those involving public goods. A canonical example is microbial bioremediation, where "cooperating" microbes detoxify their environment by secreting costly enzymes, while "cheating" mutants free-ride on this public good without contributing [9]. This creates a tragedy of the commons, where cheaters can invade and collapse the detoxification function.

Modeling these dynamics requires considering both public and private resistance mechanisms. The population dynamics in a system like a chemostat can be defined for strategies like sensitive cooperators (sCo), sensitive cheaters (sCh), resistant cooperators (rCo), and resistant cheaters (rCh) using equations that account for growth, death by toxin, and dilution [9]. A key insight is that while cooperators are often excluded by cheaters with the same private resistance level, cooperators can invade a population of cheaters if their level of toxin resistance is different [9]. This highlights the potential for environmental parameters (e.g., toxin concentration, flow rate) to control evolutionary outcomes to optimize a desired function like bioremediation.

Table 1: Key Parameters in an Evolutionary Game Theory Model of Microbial Bioremediation [9]

| Parameter | Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

x_i |

Density of strategy i |

Abundance of a microbial strain with a specific strategy. |

r_i |

Intrinsic growth rate | Maximum per capita growth rate under ideal conditions. |

δ_i(T) |

Death rate dependent on toxin T |

Mortality caused by the toxic compound in the environment. |

α |

Dilution rate | Rate of outflow from a chemostat system. |

W_i(T) |

Fitness proxy r_i / (δ_i(T) + α) |

A measure of relative fitness at a given toxin concentration. |

Experimental Evidence and Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics

Empirical studies across diverse systems have validated the significance of rapid eco-evolutionary dynamics.

Environmental Modification and Niche Adaptation

Microbes constantly modify their environment, for instance by altering pH through metabolic activity. This modification creates a feedback loop, as the changed environment selects for different microbial traits. A recent model studying the eco-evolutionary dynamics of acid-producing and alkaline-producing bacteria showed that evolutionary changes in pH preference (pH niche) can fundamentally alter ecological outcomes [10]. The system can exhibit two major regimes:

- Uniquely Stable Equilibrium: When the physiologically optimal pH for acid-producing bacteria is higher than for alkaline-producing bacteria, the system converges to an intermediate pH, and both species coexist at high population sizes. In this case, each type of bacteria evolves to prefer the pH created by the other bacteria.

- Bistable Equilibrium: When the physiologically optimal pH for acid-producing bacteria is lower than for alkaline-producing bacteria, the system has two stable equilibria—one acidophilic and one alkaliphilic—with the outcome depending on initial conditions. Here, each bacteria type evolves to prefer the pH created by its own products [10].

This demonstrates that adaptive niche changes can make predictions based on ecological theory alone difficult and underscores the necessity of incorporating evolution.

Community Context Constrains Adaptation

The surrounding biotic community is a critical factor shaping evolutionary trajectories. An experiment "caging" 22 focal bacterial strains within complex natural communities demonstrated that adaptation is not a solo endeavor but is constrained by interspecific interactions [11]. Key findings include:

- Extrinsic Factors: Focal strains showed a stronger evolutionary response and improved performance in low-diversity communities. More diverse communities appear to constrain adaptation, likely through intensified resource competition [11].

- Intrinsic Factors: Strains with larger genomes and those that were initially more maladapted to the new conditions (low pH) exhibited a greater capacity to adapt. Larger genomes may provide more pre-adaptations or genetic raw material for evolution [11].

This work confirms that ecological opportunity, granted by a permissive community context, and intrinsic genetic capacity interact to determine evolutionary outcomes.

Host-Microbiome Coevolution

The concept of eco-evolutionary feedback extends to host-associated microbiomes, giving rise to the idea of the holobiont—the host and its resident microbial community as a unit of selection. While some argue this requires a novel evolutionary framework, many interactions fit within classic coevolutionary theory [12]. Coevolution between hosts and microbiomes is evidenced by:

- Molecular Adaptations: Host-associated microbes show molecular adaptations to overcome host defenses, and hosts adapt to recruit beneficial taxa [12].

- Metabolic Collaboration: Tight interdependence, such as between insects and their bacterial symbionts for essential amino acid synthesis, demonstrates deep coevolutionary history [12].

The outcome of these interactions—whether mutualistic or antagonistic—is highly context-dependent, shaped by host genetics, the abiotic environment, and the composition of the microbial community itself [12].

Experimental Protocols for Key Eco-Evolutionary Studies

To ground theoretical concepts in practical research, detailed methodologies from key studies are provided below.

Protocol 1: Investigating Evolutionary Bioremediation in a Chemostat

This protocol is derived from evolutionary game theory models optimizing bioremediation [9].

- System Setup: Establish a chemostat with a defined medium. The system is characterized by a constant inflow of fresh medium (containing a toxin) and outflow of culture, maintaining a steady volume and dilution rate (

α). - Strain Preparation: Construct isogenic microbial strains differing only in their strategy regarding a toxic compound (e.g., heavy metal). The four key strategies are:

- Sensitive Cooperators (sCo): Degrade the toxin (public good) but are sensitive to it.

- Sensitive Cheaters (sCh): Do not degrade the toxin and are sensitive to it.

- Resistant Cooperators (rCo): Degrade the toxin and possess private resistance (e.g., efflux pumps).

- Resistant Cheaters (rCh): Do not degrade the toxin but possess private resistance.

- Initial Inoculation: Inoculate the chemostat with a monoculture of cooperating microbes (e.g., sCo or rCo).

- Environmental Manipulation: Manipulate the independent variables: toxin concentration in the inflow and the chemostat dilution rate (

α). - Monitoring and Invasion Assays: Periodically sample the chemostat to monitor population densities of each strategy using flow cytometry or selective plating. Introduce cheater mutants at known frequencies to assess their invasion dynamics.

- Maintaining Function: To overcome the inevitable invasion of cheaters and maintain detoxification, periodically reinoculate the chemostat with cooperator strains that have a different private resistance level than the dominant cheaters [9].

Protocol 2: Assessing Community Context in Bacterial Adaptation

This protocol uses a "caging" approach to study how complex communities constrain evolution [11].

- Community Sourcing: Collect environmental samples to serve as intact complex communities (e.g., from rain pools).

- Focal Strain Selection: Select a phylogenetically diverse set of focal bacterial strains from the same environment.

- Dialysis Bag Setup: Cage individual focal strains in sterile dialysis bags. These bags physically separate the focal strain from the surrounding community, preventing direct contact and horizontal gene transfer but allowing chemical interactions (e.g., resource competition, signaling).

- Microcosm Incubation: Suspend the dialysis bags in laboratory aquatic microcosms containing the intact communities. Use a defined, low-pH leaf medium to impose a consistent abiotic stress.

- Long-Term Evolution: Incubate for an extended period (e.g., 5 months), replacing only 10% of the medium weekly to mimic natural conditions and encourage competition for recalcitrant resources.

- Post-Evolution Analysis:

- Competitive Fitness: Measure the performance of evolved focal populations relative to their ancestors when grown in the same community context.

- Resource Usage: Characterize the carbon usage profile of ancestors and evolved lines using Biolog plates or specific assays for labile (xylose), intermediate (chitin), and recalcitrant (cellulose) substrates.

- Genomic Analysis: Sequence evolved populations to identify genetic changes underlying adaptation, particularly in genes related to carbon metabolism and stress response [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Studying Microbial Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Chemostat/Bioreactor | Maintains microbial populations in a constant, controlled environment for studying long-term dynamics and evolutionary rescue [9]. |

| Dialysis Bags | Physically separate a focal strain from a complex community, permitting chemical interaction but not direct contact, to study the constraining effect of communities on evolution [11]. |

| Flow Cytometer | Enables high-throughput, quantitative monitoring of population sizes and distinct microbial phenotypes in co-culture experiments over time [9]. |

| Carbon Substrate Panels (e.g., Biolog) | Phenotype microarrays that profile the metabolic capacity of ancestral and evolved strains to quantify niche width and resource usage evolution [11]. |

| Evolutionary Cellular Automata (ECA) | Individual-based computational models to simulate coevolutionary dynamics and test theoretical predictions under controlled in silico conditions [13]. |

| Remlifanserin | Remlifanserin, CAS:2289704-13-6, MF:C24H29F2N3O2, MW:429.5 g/mol |

| YM-430 | YM-430, MF:C29H35N3O8, MW:553.6 g/mol |

Visualizing Core Concepts and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core feedback loops and experimental designs central to this field.

Eco-Evolutionary Feedback Loop

This diagram visualizes the core conceptual framework of adaptive dynamics, where ecological and evolutionary processes continuously influence one another [7].

Community Constraint Experimental Workflow

This diagram outlines the key steps in the "caging" experiment used to investigate how complex communities constrain bacterial adaptation [11].

Soil organic carbon (SOC) represents the largest terrestrial carbon reservoir, playing a critical role in regulating atmospheric CO₂ concentrations and global climate. Current Earth system models (ESMs) project future climate-carbon feedbacks using simplified representations of soil carbon decomposition, often ignoring a fundamental component: the capacity of soil microbiomes to adaptively respond to warming. This case study examines how incorporating microbial eco-evolutionary dynamics into biogeochemical models reveals a potentially significant amplification of global soil carbon losses. Within the broader context of microbial adaptation to global change mechanisms research, this analysis demonstrates that functional trait adaptation in microbial communities—particularly their resource allocation strategies—can substantially accelerate soil organic matter decomposition under climate warming. By integrating eco-evolutionary theory with mechanistic modeling, we explore how temperature-driven selection on microbial physiological traits creates a positive feedback loop that may intensify climate-carbon cycle interactions.

Core Mechanisms of Microbial Adaptation to Warming

Eco-evolutionary Optimization of Microbial Functional Traits

Soil microorganisms respond to warming through both ecological and evolutionary processes that alter community composition and functional traits. Eco-evolutionary dynamics refer to temporal changes in microbial physiological and functional traits shaped by the interaction of ecological shifts (taxa selection, dispersal) and evolutionary processes (mutation, natural selection, random drift) [14]. A key mechanism involves the optimization of resource allocation strategies in response to thermal changes.

Under evolutionary game theory frameworks, microbial communities adjust trait expression to maximize fitness in changing environments. The critical trait governing soil carbon decomposition is carbon allocation to exoenzyme production (φ)—the fraction of carbon resources microbes dedicate to producing extracellular enzymes that break down soil organic matter [14]. This trait is subject to evolutionary optimization because:

- Exoenzyme production makes new resources available to the community but imposes metabolic costs on producers

- Resource allocation trade-offs force microbes to balance enzyme production against growth investment

- Temperature-sensitive kinetics alter the optimal investment strategy under different thermal regimes

Thermal Adaptation of Microbial Respiration

Beyond exoenzyme production, soil microbial communities demonstrate thermal adaptation in their fundamental respiratory processes. Research along natural geothermal gradients demonstrates that microbial communities adapt to long-term warming by shifting the temperature optima (Tₒₚₜ) and inflection point (Tᵢₙf) of their respiration [15]. Quantitative analysis reveals that:

- Tₒₚₜ adapts at a rate of 0.29°C ± 0.04 per degree of environmental warming

- Tᵢₙf adapts at a rate of 0.27°C ± 0.05 per degree of environmental warming

This partial thermal adaptation (less than 1:1 with warming) means that while microbial communities adjust to higher temperatures, their respiration rates remain elevated compared to pre-adaptation states, leading to sustained increases in carbon mineralization under warming conditions [15].

Quantifying Global Impacts: From Mechanisms to Projections

Modeling Framework and Key Findings

Incorporating microbial eco-evolutionary dynamics into global-scale models reveals substantial impacts on projected soil carbon losses. The mechanistic modeling approach extends the Allison–Wallenstein–Bradford (AWB) microbe-enzyme model by making the exoenzyme production trait (φ) an evolutionarily optimized variable rather than a fixed parameter [14].

Table 1: Key Model Parameters and Temperature Dependencies

| Parameter | Symbol | Temperature Dependence | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum decomposition rate | vₘâ‚â‚“á´° | Arrhenius relationship | Controls maximum SOC decomposition rate by enzymes |

| Half-saturation constant | Kₘᴰ | Arrhenius relationship | Enzyme-substrate affinity parameter |

| Maximum uptake rate | vₘâ‚â‚“áµ | Arrhenius relationship | Microbial carbon uptake capacity |

| Carbon allocation to enzymes | φ* | Eco-evolutionary optimization | Fraction of carbon allocated to exoenzyme production |

| Microbial growth efficiency | CUE | Varies with community composition | Carbon conversion efficiency to biomass |

When applied globally under climate warming scenarios (e.g., RCP8.5), models incorporating eco-evolutionary optimization project that microbial adaptation significantly amplifies soil carbon loss compared to models with static microbial traits [14] [16]. The key quantitative findings include:

Table 2: Projected Global Soil Carbon Loss with and without Microbial Adaptation

| Model Scenario | Projected Soil Carbon Loss by 2100 | Amplification Factor | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional kinetics-only model | Baseline projection | 1.0x | Temperature-enhanced enzyme kinetics only |

| Eco-evolutionary model | Approximately 2x baseline [14] | ~2.0x | Combined kinetic effects + increased enzyme allocation |

| Regional variation | Greatest in mid-high latitudes [14] | Spatially heterogeneous | Interaction with initial carbon stocks and warming magnitude |

The spatial patterns of amplified carbon loss are not uniform globally. Regions with significant soil carbon stocks and substantial warming—particularly northern latitudes—show the strongest responses, creating geographic "hotspots" of vulnerability to microbial adaptation effects [14].

Microbial Community Composition and Diversity Responses

Concurrent with functional trait adaptation, warming restructures soil microbial communities in ways that further influence carbon cycling:

- Diversity reductions: Long-term warming significantly reduces soil microbial richness, particularly fungal diversity, with stronger declines observed in regions with higher baseline temperatures and lower nitrogen availability [17]

- Abundance increases: Despite diversity losses, total microbial abundance often increases under warming, reflecting a decoupling between community complexity and population size [17]

- Functional gene shifts: Warming suppresses ammonia-oxidizing bacteria while increasing denitrifiers, indicating broader restructuring of biogeochemical cycling communities [17]

- Community resistance: In agricultural systems, microbial community resistance to warming correlates with reduced carbon loss, highlighting the stabilizing potential of certain community configurations [18]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Eco-evolutionary Modeling Framework

The foundational methodology for quantifying microbiome adaptation effects employs a mechanistic biogeochemical model with integrated eco-evolutionary optimization [14]. The core components include:

Model Structure: The baseline microbe-enzyme model extends the AWB framework with four state variables:

- Soil organic carbon (C)

- Dissolved organic carbon (D)

- Microbial biomass (M)

- Enzyme pool (Z)

System Dynamics: The model simulates carbon flows through these pools using differential equations:

dC/dt = I - e_C·C - (v_max^D·C/(K_m^D + C))·Z [14]

dM/dt = (1-φ)·γ_M·(v_max^U·D/(K_m^U + D))·M - d_M·M [14]

dZ/dt = φ·γ_Z·(v_max^U·D/(K_m^U + D))·M - d_Z·Z [14]

Eco-evolutionary Optimization: The critical innovation involves determining the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) for φ (enzyme allocation) using evolutionary game theory. The optimization process:

- Identifies feasible phenotype range (φmin, φmax)

- Tests invasion potential of mutant strategies against residents

- Selects the ESS (φ*) that cannot be invaded by alternatives

- Recaluclates φ* as temperature changes over time

Parameterization: Model parameters are derived from meta-analyses of soil microbial traits and calibrated against observed respiration rates. Temperature dependencies follow Arrhenius relationships for microbial uptake and enzyme kinetic parameters [14].

Thermal Adaptation Quantification Protocol

Experimental quantification of thermal adaptation in microbial respiration employs geothermal gradients as natural warming experiments [15]:

Site Selection:

- Samples collected across natural geothermal gradients (soil temperatures: 11-35°C)

- Paired with regional climate gradient samples

- encompassing diverse edaphic conditions and ecosystem types

Temperature Response Curves:

- Incubations conducted across 11+ temperature points (~4-42°C)

- Glucose amendments eliminate substrate limitation confounding effects

- COâ‚‚ flux measurements using infrared gas analysis

- Mathematical separation of glucose-derived vs. SOC-derived respiration

MMRT Curve Fitting:

- Application of Macromolecular Rate Theory (MMRT) to temperature responses

- Estimation of Tₒₚₜ and Tᵢₙf for each community

- Regression of Tₒₚₜ and Tᵢₙf against mean annual temperature

- Calculation of adaptation rates using spatial autocorrelation models

Conservation Agriculture Warming Experiment

Long-term field experiments examining management-warming interactions provide empirical validation [19]:

Experimental Design:

- 10-year field experiment with factorial design

- Management treatments: Conservation vs. Conventional agriculture

- Warming treatments: +2°C via infrared heaters vs. ambient

- Continuous monitoring of soil temperature, moisture

Measurements:

- SOC content via repeated soil sampling

- Microbial community composition (DNA sequencing)

- Microbial carbon use efficiency (H₂¹â¸O labeling)

- Microbial necromass (amino sugar biomarkers)

- Plant carbon inputs (biomass, root exudates)

Statistical Analysis:

- Structural equation modeling to identify causal pathways

- Time-series analysis of treatment effects

- Cohen's d effect size quantification over time

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application in Microbiome Adaptation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | H₂¹â¸O labeling | Quantifies microbial carbon use efficiency and growth rates in situ [19] |

| Molecular Biomarkers | Amino sugars (glucosamine, muramic acid) | Differentiates fungal vs. bacterial necromass contributions to SOC [19] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | DNA/RNA extraction kits | Characterizes microbial community composition via metagenomics/transcriptomics [17] [19] |

| Enzyme Assays | Fluorometric substrates (MUB-linked) | Measures exoenzyme activities for C, N, P acquisition [14] |

| Respiratory Measurements | Infrared gas analyzers (IRGA) | Quantifies temperature response curves of microbial respiration [15] |

| Modeling Platforms | R, Python with DE solving libraries | Implements mechanistic models with eco-evolutionary optimization [14] |

This case study demonstrates that microbial eco-evolutionary adaptation to warming represents a significant mechanism amplifying global soil carbon losses. The integration of trait-based optimization into biogeochemical models reveals that adaptive shifts in exoenzyme production may potentially double projected soil carbon emissions by 2100 compared to traditional models. These findings highlight critical limitations in current Earth system models and underscore the necessity of incorporating microbial evolutionary dynamics into climate projections. Future research priorities should include: (1) expanded quantification of microbial trait variation across global gradients, (2) development of more sophisticated multi-trait optimization frameworks, and (3) integration of microbial adaptation with other global change factors such as altered precipitation patterns and nitrogen deposition. Understanding and accurately modeling these microbial mechanisms is essential for predicting climate-carbon feedbacks and developing effective climate mitigation strategies.

Stress-Induced Mutagenesis and the Role of Bacteriophages in Genome Plasticity

Bacterial genomes exhibit remarkable plasticity, enabling rapid adaptation to environmental stressors. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of two fundamental drivers of microbial evolution: stress-induced mutagenesis and bacteriophage-mediated genetic renovation. We examine molecular mechanisms whereby bacteria increase mutation rates under stress conditions including nutrient deprivation, antibiotic exposure, and DNA damage. Furthermore, we explore how temperate bacteriophages serve as hotspots for genetic innovation through lysogenic integration and formation of "grounded" prophages. The intricate interplay between stress responses and phage-host interactions creates a powerful engine for bacterial adaptation with significant implications for antimicrobial resistance, pathogen evolution, and therapeutic development. Technical protocols, quantitative datasets, and visualization tools provided herein offer researchers comprehensive resources for investigating these fundamental processes in microbial evolution.

Microbial success across diverse ecosystems stems from sophisticated adaptation mechanisms centered on genome plasticity. Bacteria possess global response systems that implement sweeping changes in gene expression and cellular metabolism when encountering stressors including nutritional deprivation, DNA damage, temperature shift, and antibiotic exposure [20]. These responses are controlled by master regulators encompassing alternative sigma factors (RpoS, RpoH), small molecule effectors (ppGpp), gene repressors (LexA), and inorganic molecules (polyphosphate) [20] [21].

Beyond chromosomal mutations, bacteria leverage horizontal gene transfer (HGT) through transformation, conjugation, and transduction to acquire adaptive traits. Temperate bacteriophages play particularly significant roles in bacterial evolution through lysogeny, where the phage genome integrates into the host chromosome as a prophage [22] [23]. These integrated elements can subsequently serve as platforms for genetic renovation and innovation. The emerging paradigm reveals that stress-induced mutagenesis and phage-mediated genetic exchange operate synergistically to accelerate bacterial evolution, with profound implications for understanding microbial responses to global change pressures including antibiotic usage and environmental disruption.

Molecular Mechanisms of Stress-Induced Mutagenesis

Global Stress Responses and Mutagenic Pathways

Under stressful conditions, bacteria enter a transient mutator state that increases genetic variability, potentially accelerating adaptive evolution [20]. Several overlapping global stress responses contribute to this phenomenon:

Table 1: Major Bacterial Stress Responses with Mutagenic Consequences

| Stress Response | Primary Inducers | Key Regulators | Mutagenic Elements | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOS Response | DNA damage, antibiotics | LexA, RecA | Pol IV, Pol V, Pol II | DNA repair, mutagenic lesion bypass |

| General Stress Response | Starvation, stationary phase | RpoS (σS) | Downregulation of error-correcting enzymes | Survival under nutrient limitation |

| Sigma E Response | Membrane stress | RpoE (σE) | Promotes spontaneous DSBs | Envelope protein folding stress |

| Stringent Response | Nutrient starvation | (p)ppGpp | Modulation of replication fidelity | Metabolic adaptation |

The SOS response to DNA damage represents the most extensively characterized mutagenic pathway. Following DNA damage, RecA nucleoprotein filaments form on single-stranded DNA, stimulating self-cleavage of the LexA repressor and derepression of approximately 30 SOS genes [20]. Key among these are error-prone DNA polymerases, including Pol II (encoded by polB), Pol IV (dinB), and Pol V (umuDC), which can replicate past DNA lesions but exhibit low fidelity when copying undamaged templates [20].

The general stress response, governed by RpoS (σS), activates in response to nutrient deprivation and other challenges, resulting in downregulation of error-correcting enzymes and upregulation of alternative genetic change mechanisms [20]. These responses extensively overlap and can be induced to various extents by the same environmental stresses, creating integrated networks that regulate mutagenesis.

Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenic DNA Break Repair

Stress-induced mutagenesis occurs through defined molecular mechanisms, particularly in starving Escherichia coli, where DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair becomes mutagenic via two primary pathways:

Homologous Recombination (HR)-Based Mutagenic Break Repair requires three simultaneous events [24]:

- DSB formation and repair initiation: Spontaneous DSBs occur in ≤1% of growing E. coli, with some promoted by the sigma E membrane stress response

- SOS response activation: Induced in approximately 25% of cells with a reparable DSB, leading to transcriptional upregulation of error-prone polymerases

- General stress response activation: Triggered by various stressors, permitting mutagenic repair

HR-MBR depends on cellular analogs of human cancer proteins: RecBCD (analogous to BRCA2) loads RecA (ortholog of RAD51) onto single-stranded DNA at DSBs, enabling strand exchange with homologous sequences [24]. In unstressed cells, this repair uses high-fidelity Pol III, but under stress conditions, error-prone polymerases are recruited.

Microhomology-Mediated Break-Induced Replication (MMBIR) generates copy-number alterations and genomic rearrangements through microhomologous sequences [24]. This pathway mirrors genomic instability patterns observed in many cancers and may contribute to stress-induced adaptation across phylogeny.

Error-Prone DNA Polymerases in Stress-Induced Mutagenesis

Specialized DNA polymerases play crucial roles in stress-induced mutagenesis. In normally growing, undamaged cells, Pol IV and Pol V contribute little to spontaneous mutation rates [20]. However, during stress:

- Pol IV (DinB): Uninduced cells contain approximately 250 molecules of Pol IV [20]. SOS induction increases Pol IV levels 10-fold, and it becomes required for most HR-MBR-generated base substitutions and indels [24].

- Pol V (UmuDC): Cellular levels are undetectable without SOS induction [20]. During stress, Pol V contributes to mutagenesis at specific sites.

- Pol II: Promotes some MBR indels and may restart stalled replication forks [20].

These specialized polymerases compete with each other and with replicative polymerases at stalled replication forks, with outcomes determined by their relative concentrations and regulation under stress conditions.

Diagram 1: Stress-induced mutagenesis pathway integrating multiple stress responses to generate genetic diversity during adaptation.

Bacteriophages as Drivers of Genome Plasticity

Prophage Integration and Lysogenic Conversion

Temperate bacteriophages significantly contribute to bacterial genome evolution through lysogeny. Analysis of 69 strains of Escherichia and Salmonella reveals approximately 500 prophages integrated in specific patterns relative to host genome organization [22]. Phage integrases often target conserved genes and intergenic positions, suggesting purifying selection for integration sites that minimize disruption to host fitness [22].

Integration sites display nonrandom organization relative to the origin-terminus axis and macrodomain structure of bacterial chromosomes [22]. Lambdoid prophages systematically co-orient their genes with the bacterial replication fork and contain host-required motifs such as FtsK-orienting polar sequences for chromosome segregation, while avoiding motifs like matS that disrupt macrodomain organization [22]. This precise adaptation reflects strong natural selection for seamless prophage integration.

Lysogeny provides several selective advantages:

- Immunity against secondary infection: Prophages typically express repressors that prevent superinfection by related phages [23]

- Horizontal gene transfer: Transduction moves bacterial DNA between cells

- Lysogenic conversion: Prophages can carry cargo genes encoding virulence factors, stress tolerance mechanisms, or novel metabolic pathways [22]

"Grounded" Prophages as Genetic Buffers

Mutations in attachment sites or recombinase genes can prevent prophage excision, creating "grounded" (cryptic or defective) prophages [23]. These elements offer several advantages:

- Immune protection without induction risk: Grounded prophages provide immunity against secondary phage infection while avoiding cell lysis from lytic cycle activation [23]

- Genetic buffer zones: These regions expedite bacterial genome evolution by increasing the frequency and diversity of variations including inversions, deletions, and insertions via horizontal gene transfer [23]

- Hotspots for innovation: Grounded prophages serve as integration sites for ecologically significant genes involved in stress tolerance, antimicrobial resistance, and novel metabolic pathways [23]

Sequence analyses of E. coli grounded prophages (DLP12, e14, Rac, CPZ-55, and Qin) demonstrate their roles in bacterial ecology and evolution through these mechanisms [23]. The prevalence of multiple grounded prophages across bacterial genomes indicates eco-evolutionary selection for genomes containing these elements.

Phage-Driven Phenotypic Heterogeneity

Beyond genetic changes, phage infections generate phenotypic heterogeneity within isogenic microbial populations through several mechanisms [25]:

- Heterogeneous infection status: Not all cells become infected simultaneously, creating metabolic and physiological diversity between infected and uninfected subpopulations

- Differential infection progression: Individual cells may exist at different infection stages, from early viral genome replication to imminent lysis or stable lysogeny

- Metabolic reprogramming: Phage infection alters host metabolism to support viral replication, creating distinct physiological states

This phenotypic heterogeneity represents a form of bet-hedging, allowing microbial populations to maintain subpopulations with different characteristics, potentially enhancing resilience to environmental perturbations [25]. Phage-driven phenotypic heterogeneity influences microbial community structure, evolutionary trajectories, and ecosystem functions including biogeochemical cycling.

Diagram 2: Bacteriophage life cycles and the formation of grounded prophages that serve as hotspots for genetic innovation.

Quantitative Analysis of Mutation Patterns and Genomic Plasticity

Stress-Induced Mutagenesis Systems Across Bacterial Species

Table 2: Experimentally Characterized Systems of Stress-Induced Mutagenesis

| System Name | Organism | Mutation Type | Selected Phenotype | Genetic Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starvation-induced Mu-mediated fusions | E. coli | Transposition | Growth on arabinose plus lactose | RpoS, ClpP, HNS* |

| ROSE mutagenesis | E. coli | Base substitutions | Rifampicin resistance | CyaA, RecA, LexA*, UvrB, Pol I |

| Mutagenesis in aging colonies (MAC) | E. coli | Base substitutions | Rifampicin resistance | RpoS, Crp, CyaA, RecA, MMR*, Pol II |

| SOS-dependent spontaneous mutagenesis | E. coli | Base substitutions | Tryptophan prototrophy | RecA, Pol V |

| Stationary-phase mutagenesis | P. putida | Frameshifts, base substitutions, transposition | Growth on phenol | Pol IV, Pol V, RpoS, MutY |

| Stationary-phase mutagenesis | B. subtilis | Base substitutions | Amino acid prototrophy | ComA, ComK, Pol IV, MMR*, Mfd |

| Adaptive mutation | E. coli | Frameshifts | Growth on lactose | Pol IV, RecA, RecBCD, RpoS, GroE, Ppk |

Note: * indicates loss or inactivation of the gene is required [20]

Measuring Genome Plasticity: Novel Metrics

Understanding bacterial genome plasticity requires quantitative metrics that capture the rate of genetic change. Traditional measures like Jaccard distance applied to gene content and genome fluidity offer insights into gene repertoire diversity but lack temporal resolution [26]. A novel index, Flux of Gene Segments (FOGS), incorporates evolutionary distance to assess the rate of gene exchange, better capturing genome plasticity [26].

The FOGS methodology involves:

- Orthology group classification: PanTA classifies all proteins into orthology groups

- Neighborhood network construction: Builds gene adjacency graphs for each genome

- Pairwise comparison: Identifies unique gene segments between genomes

- Segment compression: Considers consecutive unique genes as single elements

- Event calculation: Sums unique gene segments representing gain/loss events

- Evolutionary weighting: Weightes events by SNP distance without requiring dated phylogenies [26]

Application of FOGS to Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli reveals distinctive plasticity patterns in specific sequence types and clusters, suggesting correlation between heightened genome plasticity and globally recognized high-risk clones [26].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Protocol for Assessing Stress-Induced Mutagenesis in E. coli

Objective: Quantify mutation rates in bacterial populations under nutrient starvation stress.

Materials:

- E. coli strains with chromosomal mutation reporter genes (e.g., lacZ alleles)

- M9 minimal medium with limiting carbon sources

- Rich media (LB) for control conditions

- Selective plates containing antibiotics or specific carbon sources

Procedure:

- Inoculate single colonies into 5mL LB and grow overnight at 37°C with shaking

- Wash cells twice in sterile saline to remove residual nutrients

- Resuspend in M9 minimal medium with suboptimal carbon source (e.g., 0.02% lactose)

- Plate aliquots on selective media immediately (day 0) to determine pre-existing mutants

- Incubate remaining culture without additional nutrients at 37°C

- Plate aliquots on selective media at daily intervals (days 1-7) to quantify emerging mutants

- Parallel plate on non-selective media to determine viable cell counts

- Calculate mutation rates using fluctuation analysis or maximum likelihood methods

Key Considerations:

- Include isogenic strains with mutations in key genes (recA, rpoS, dinB) to determine genetic requirements

- Monitor stress response activation using appropriate reporters (e.g., GFP fusions)

- Account for potential amplification events that may precede mutation [20] [24]

Protocol for Prophage Induction and Characterization

Objective: Induce and characterize prophages from bacterial genomes.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains with suspected prophages

- Mitomycin C or other inducing agents

- Phage buffer (10mM Tris, 10mM MgSOâ‚„, 68mM NaCl, pH 7.5)

- Soft agar for overlay assays

- Indicator strains for phage titration

- DNase I, RNase A, proteinase K for DNA extraction

Procedure:

- Grow bacterial culture to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ~0.3-0.4)

- Add mitomycin C to final concentration of 0.1-1.0μg/mL

- Continue incubation with shaking for 3-6 hours until lysis observed

- Centrifuge culture to remove cell debris

- Filter sterilize supernatant through 0.22μm filter

- Confirm phage presence by spot test on indicator lawn

- Quantify phage titer using double-layer agar method

- Extract phage DNA for sequencing and analysis

- For grounded prophages, attempt induction with multiple agents and examine excision by PCR

Analysis:

- Sequence prophage regions and compare with known phage databases

- Identify integration sites and attachment sequences

- Characterize potential virulence factors or other cargo genes

- Assess impact on host fitness through competition assays [22] [23]

Single-Cell Analysis of Phage-Induced Heterogeneity

Objective: Resolve phenotypic heterogeneity during phage infection at single-cell level.

Materials:

- Microfluidic device for single-cell trapping

- Stable isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., ¹âµN-ammonium, ¹³C-glucose)

- Bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT) reagents

- FISH probes targeting phage or host genes

- NanoSIMS or Raman spectroscopy equipment

Procedure:

- Load bacterial culture into microfluidic device

- Introduce phage particles at desired multiplicity of infection

- Pulse with stable isotope-labeled substrates or BONCAT reagents

- Fix cells at various timepoints post-infection

- Perform FISH/HISH for viral or host gene expression

- Analyze by NanoSIMS for isotopic incorporation or mass spectrometry for proteomics

- Correlate metabolic activity with infection progression

- Model heterogeneity using statistical approaches [25]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Stress-Induced Mutagenesis and Phage Biology

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | E. coli K-12 MG1655 (wild-type); Isogenic mutants (ΔrecA, ΔrpoS, ΔdinB) | Genetic requirement determination | Defined genotypes enable mechanistic studies |

| Reporter Systems | lacZ frameshift alleles; GFP fusions to stress response promoters | Mutation rate quantification; Stress response monitoring | Sensitive detection of rare events; Real-time monitoring |

| Error-Prone Polymerase Expression Plasmids | Inducible dinB (Pol IV); umuDC (Pol V) | Polymerase-specific mutagenesis analysis | Controlled expression without SOS induction |

| Phage Induction Agents | Mitomycin C; Norfloxacin; UV light | Prophage induction and characterization | Different induction mechanisms; Dose-responsive |

| Metabolic Labels | ¹âµN-ammonium sulfate; ¹³C-glucose; BONCAT reagents | Single-cell metabolic tracking | Compatible with NanoSIMS; Non-disruptive incorporation |

| SNP Distance Analysis Tools | P-DOR pipeline; snp-dists | Evolutionary distance calculation | Handles large datasets; Recombination filtering |

Implications for Antimicrobial Resistance and Therapeutic Development

The interplay between stress-induced mutagenesis and phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer has profound implications for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) development. Stress responses to antibiotic exposure can increase mutation rates, generating genetic diversity that includes resistance mutations [27] [24]. Simultaneously, phages can disseminate resistance genes through transduction, creating a dual threat for rapid resistance evolution.

Notably, subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations can induce stress responses that increase mutagenesis, potentially accelerating resistance development. Fluoroquinolones, for instance, induce the SOS response by causing DNA breaks, thereby activating error-prone polymerases that generate mutations, some of which may confer resistance [27]. This relationship suggests potential anti-evolvability strategies targeting stress-induced mutagenesis mechanisms rather than bacterial viability itself.

Potential therapeutic approaches include:

- SOS response inhibitors: Compounds that prevent LexA cleavage or RecA activation

- Polymerase-specific inhibitors: Molecules that selectively block error-prone polymerase activity

- Phage therapy engineering: Modified phages that exploit stress response pathways or deliver anti-mutator genes

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying stress-induced mutagenesis and phage-driven genome plasticity provides crucial insights for developing novel interventions against bacterial adaptation, with applications spanning clinical medicine, agricultural science, and environmental management.

Stress-induced mutagenesis and bacteriophage activity represent complementary engines of bacterial genome evolution. Stress responses temporally regulate mutagenesis, increasing genetic diversity specifically when organisms are maladapted to their environment. Meanwhile, temperate phages spatially organize genetic innovation through targeted integration and formation of grounded prophages that serve as genetic buffer zones. The integration of these mechanisms—temporal control of mutation rates and spatial organization of genetic elements—creates a sophisticated system for bacterial adaptation to changing environments.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Elucidating how different stressors specifically modulate mutation mechanisms and spectra

- Characterizing phage integration patterns across diverse bacterial taxa

- Developing quantitative models that predict adaptation rates based on stressor intensity and duration

- Exploring evolutionary conservation of these mechanisms from bacteria to cancer cells

Technical advances in single-cell analysis, including NanoSIMS, BONCAT-FISH, and microfluidics, will enable unprecedented resolution in studying these processes. Combined with emerging genome plasticity metrics like FOGS, these approaches will enhance our ability to predict and potentially intervene in bacterial adaptation processes with significant implications for managing antimicrobial resistance and understanding microbial responses to global change.

Tracking and Engineering Microbial Adaptation: From Labs to Ecosystems

Genomic and Metagenomic Tools for Deciphering Adaptive Traits

Microbial adaptation is a cornerstone of planetary resilience, enabling ecosystems to respond to rapid global environmental changes. Understanding the genetic and functional basis of these adaptations is critical for predicting ecosystem trajectories and developing mitigation strategies [8]. The emergence of sophisticated genomic and metagenomic tools has revolutionized our ability to decipher these adaptive traits, moving beyond simple community profiling to a mechanistic understanding of microbial responses. These technologies allow researchers to link molecular-level shifts—from single-nucleotide variants to horizontal gene transfer—to population dynamics and ecosystem-level outcomes, thereby bridging critical scales in microbial ecology [8] [28]. This technical guide examines the capabilities of these tools within the context of microbial adaptation to global change, providing researchers with advanced methodologies for uncovering the functional potential of microbial "dark matter" and its role in environmental resilience.

Core Concepts of Adaptive Traits

An adaptive trait can be defined as a heritable characteristic that enhances an organism's fitness—its survival and reproductive success—in a specific environment. In microbial systems, these traits span multiple biological scales, from single-gene mutations conferring antibiotic resistance to complex metabolic pathways enabling survival under osmotic or thermal stress.

- Local Adaptation: This occurs when resident genotypes develop higher relative fitness in their local environment compared to genotypes from other environments through the action of natural selection. This is a key concept for understanding microbial population structure and for informing conservation actions such as translocations for restoration or assisted gene flow [29].

- Distinguishing Adaptive from Neutral Variation: A fundamental challenge in microbial genomics is differentiating genetically based adaptations from changes due to random genetic drift. Drift, a stochastic process that changes allele frequencies over time, operates more quickly in small populations and decreases genetic variation while driving alleles toward fixation. Genomic tools are particularly powerful for this discrimination, as they can analyze thousands to millions of genetic markers, moving beyond the limited resolution of traditional genetic studies that use smaller sets of markers to address primarily neutral processes like gene flow and drift [29].

Table 1: Key Definitions in the Study of Adaptive Traits

| Term | Definition | Relevance to Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Local Adaptation [29] | Resident genotypes have higher relative fitness in their local environment than genotypes from other environments. | Indicates population-specific evolutionary response to local environmental conditions. |

| Genetic Drift [29] | A change in allele frequencies over time due to stochastic processes. | Can be confused with selection; emphasizes need for robust statistical detection of adaptive traits. |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) [28] | A genome reconstructed from mixed microbial community sequencing data. | Enables study of adaptive traits in uncultured microorganisms. |

| Stenohaline [30] | Organisms thriving within a narrow range of salinity. | Demonstrates specific adaptation to a stable environmental factor. |

| Euryhaline [30] | Organisms capable of adapting to wide salinity fluctuations. | Demonstrates adaptation to environmental variability and fluctuation. |

Genomic Approaches for Detecting Adaptation

Genomic approaches focus on the DNA of individual organisms or populations, aiming to identify signatures of natural selection within genomes. These methods are essential for pinpointing the specific genetic variants underlying adaptive phenotypes.

Genome-Wide Scans for Selection

Genome-wide scans analyze patterns of genetic variation across many genomes to identify regions that have undergone recent positive selection. These methods detect characteristic signatures left by selective sweeps, where a beneficial mutation rapidly increases in frequency, carrying linked neutral variants along with it.

- The Composite of Multiple Signals (CMS) test is a powerful method for fine-mapping signals of natural selection. It combines several independent population genetic statistics that collectively distinguish the causal adaptive variant from neighboring neutral variants. This approach can narrow down candidate regions to a tractable number of variants (e.g., 20-100 candidates per region), significantly advancing the identification of causal mutations from large genomic datasets [31].

- Considerations for Experimental Design: Successful genomic assessment of local adaptation requires careful planning. Studies must be designed to distinguish selective sweeps from other demographic events, such as population bottlenecks or expansions. The choice of populations for comparison is critical; populations from contrasting environmental conditions provide the most power for detecting adaptive loci. Furthermore, the decision to use genomic approaches should be weighed against alternatives; in some cases, assessing adaptive variation might be more efficiently accomplished through common garden experiments or reciprocal transplants, where organisms from different environments are raised in a common environment or swapped between environments, respectively, to determine the genetic basis of observed differences [29].

Identifying Adaptive Variants and Functions

Once genomic regions under selection are identified, the next step is to elucidate the function of the candidate adaptive variants and their link to phenotypic traits.

- Variant Annotation and Functional Prediction: High-scoring candidate variants from tests like CMS are subjected to extensive functional annotation. This process includes:

- Identifying non-synonymous mutations that alter protein sequences.

- Mapping variants to regulatory regions that might affect gene expression levels of nearby genes or long non-coding RNAs.

- Using protein structure modeling to predict the functional consequences of amino acid changes.

- Examining evolutionary conservation via tools like GERP scores, which measure sequence constraint and can highlight functionally important residues [31].

- Linking Adaptation to Phenotype: A compelling example is the identification of a non-synonymous mutation in the TLR5 gene, which encodes a toll-like receptor involved in immune response. Genomic scans identified this variant as a strong candidate for selection. Subsequent functional characterization revealed that the variant alters NF-κB signaling in response to bacterial flagellin, providing a mechanistic link between the genetic adaptation and an immune phenotype [31]. This demonstrates a complete pipeline from genomic discovery to functional validation.

Table 2: Genomic Methods for Detecting Adaptive Traits

| Method | Key Principle | Data Outputs | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMS Test [31] | Combines multiple population genetic statistics (e.g., long haplotypes, population differentiation) to pinpoint causal variants. | A refined list of candidate causal variants within genomic regions under selection. | Fine-mapping adaptive variants from large candidate regions identified in genome scans. |

| Outlier Detection [29] | Identifies loci with exceptionally high genetic differentiation (F~ST~) compared to the genomic background. | A set of loci potentially under divergent selection between populations. | Detecting local adaptation in populations inhabiting different environments. |

| Pangenome Analysis [28] | Compares the total set of genes across multiple genomes of a species or group. | Core genome (shared genes) and accessory genome (variable genes). | Understanding within-species diversity, horizontal gene transfer, and niche adaptation. |

Metagenomic Approaches for Deciphering Community Adaptation

Metagenomics involves the direct sequencing and analysis of the collective genomic material from entire microbial communities, providing a powerful lens to study adaptation without the need for cultivation.

Whole-Genome Shotgun Metagenomics

The Whole-Genome Shotgun (WGS) approach involves randomly shearing and sequencing all DNA from an environmental sample, enabling simultaneous assessment of taxonomic composition and functional potential [32].

- From Reads to Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): The analysis typically involves a critical step called de novo assembly, where short sequencing reads are reconstructed into longer contiguous sequences (contigs) based on overlapping regions. These contigs are then binned into MAGs based on sequence composition (e.g., k-mer frequency) and abundance profiles across multiple samples. MAGs represent draft genomes of uncultured organisms and are the foundation of genome-resolved metagenomics [28]. This approach has been a game-changer, allowing researchers to study the genetic makeup, functional capacity, and evolutionary history of previously inaccessible microbial lineages [28].