Microbial Community Assembly Methods: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Understanding microbial community assembly is pivotal for advancing biomedical research, from manipulating the human microbiome to developing novel antimicrobial strategies.

Microbial Community Assembly Methods: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Understanding microbial community assembly is pivotal for advancing biomedical research, from manipulating the human microbiome to developing novel antimicrobial strategies. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of modern microbial community assembly methods, catering to researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational ecological principles, details established and emerging construction techniques, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and provides a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of different approaches. By synthesizing current methodologies and their applications, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select, implement, and optimize the most appropriate assembly strategies for their specific research and development goals.

The Ecological Basis of Microbial Community Assembly: From Principles to Practice

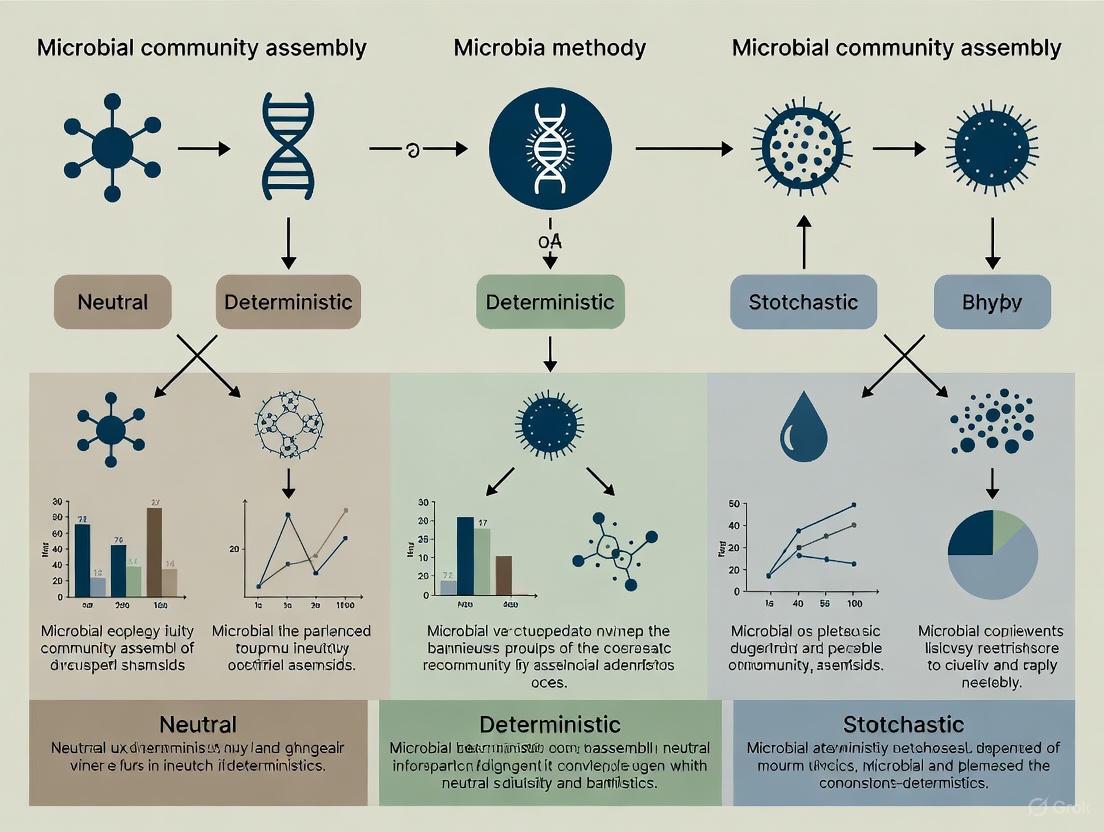

Understanding the mechanisms that govern microbial community assembly is a central goal in microbial ecology. The structure and function of these communities are shaped by the interplay of two fundamental types of ecological processes: deterministic processes, which are niche-based and predictable, and stochastic processes, which are neutral and driven by chance. Deterministic processes include environmental filtering by abiotic factors like pH and temperature, as well as biological interactions such as competition and symbiosis. In contrast, stochastic processes encompass random birth-death events (ecological drift), dispersal limitations, and random colonization. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the roles these processes play across different ecosystems, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform research and drug development efforts.

Quantitative Comparison of Ecological Processes Across Ecosystems

The relative influence of deterministic and stochastic processes varies significantly across ecosystem types, environmental conditions, and temporal scales. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Influence of Deterministic and Stochastic Processes Across Ecosystems

| Ecosystem | Dominant Process | Quantitative Contribution | Key Influencing Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine Lake (Annual Scale) | Deterministic (Homogeneous Selection) | 66.7% of community turnover | Consistent annual environmental conditions | [1] |

| Alpine Lake (Short-Term) | Stochastic (Homogenizing Dispersal) | 55% of community turnover | Daily/weekly sampling scale | [1] |

| Soil Ecosystems | Abundant Taxa & Generalists: DeterministicRare Taxa & Specialists: Stochastic | Varies by ecotype | Universal abiotic factors (e.g., soil pH, calcium); ecosystem type | [2] |

| Grassland Soils | Deterministic (Homogeneous Selection) & Stochastic (Dispersal) | Mediated by precipitation | Precipitation gradients; soil moisture | [3] |

| Biofilters (Wastewater) | Stochastic | 89.9% of variation explained by Neutral Community Model | Operation phase; biofilm development; rare taxa dynamics | [4] [5] |

| Cold-Water Fish Gut | Deterministic | Greater than stochastic processes | Seasonal variation (summer vs. winter) | [6] |

| Subsurface Microbial Communities | Deterministic (Environmental Filtering) | Maximized at ends of environmental gradients | Temporal and spatial environmental variability | [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Disentangling Assembly Processes

Researchers employ a suite of standardized molecular and computational protocols to quantify the role of deterministic and stochastic processes.

Field Sampling and DNA Sequencing

- Sample Collection: Studies typically involve systematic spatiotemporal sampling. For example, in freshwater studies, composite water samples are collected from multiple depths using a Schindler-Patalas sampler [1]. In soil studies, samples are collected from multiple plots across large-scale transects [2] [3].

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: Total genomic DNA is extracted from filters (water) or soil cores using commercial kits (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil, QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit) [1] [8] [6].

- Sequencing: The 16S rRNA gene (for bacteria/archaea) or 18S rRNA gene (for microeukaryotes) is amplified using universal primers (e.g., 515F/909R) and sequenced on Illumina platforms (MiSeq, HiSeq) [1] [8] [6].

Bioinformatics and Community Analysis

- Sequence Processing: Raw sequences are processed using pipelines like QIIME or QIIME2 with DADA2 to resolve amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or cluster operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold [1] [8] [6].

- Diversity Metrics: Alpha diversity (richness, evenness) and beta diversity (community dissimilarity) are calculated using metrics such as Bray-Curtis, weighted UniFrac, and Jaccard distances [2] [6].

Statistical Modeling of Ecological Processes

- Null Model Analysis: This is a cornerstone method. The infer Community Assembly Mechanisms by Phylogenetic Bin-based null Model (iCAMP) framework is widely used. It employs the beta Nearest Taxon Index (βNTI) and Raup-Crick (RCbray) metric to quantify the relative importance of different processes [2] [6].

- |βNTI| > 2 indicates deterministic selection.

- |βNTI| < 2 and |RCbray| > 0.95 indicates homogenizing dispersal or dispersal limitation.

- |βNTI| < 2 and |RCbray| < 0.95 indicates an dominant role of ecological drift [2].

- Neutral Community Model (NCM): This model, proposed by Sloan et al., predicts the relationship between OTU detection frequency and its relative abundance based on random immigration and ecological drift. The model's R² value indicates the fraction of community variation explained by neutral processes [4] [8] [5].

- Variation Partitioning Analysis (VPA): This method uses multiple regression to disentangle the pure and shared effects of environmental factors and spatial distance on community composition, helping to distinguish environmental selection (deterministic) from dispersal limitation (stochastic) [5].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for analyzing community assembly mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Assembly Rule Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from diverse sample types. | FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals), QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) [8] [6]. |

| Universal PCR Primers | Amplification of target rRNA genes for community profiling. | 515F/907R (16S rRNA), 515F/909R (16S rRNA) [8] [6]. |

| Sequencing Platform | High-throughput sequencing of amplicon libraries. | Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq platforms (2x300 bp paired-end common) [8] [6]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Processing raw sequence data into analyzed community metrics. | QIIME/QIIME2, DADA2 for ASV inference, USEARCH for OTU clustering [1] [8]. |

| Reference Database | Taxonomic classification of sequence variants. | Greengenes, SILVA, UNITE [8]. |

| Statistical Environment | Data analysis, visualization, and ecological modeling. | R environment with packages like phyloseq, vegan, iCAMP, NST [2] [6]. |

| Sample Collection Gear | Standardized collection of environmental samples. | Schindler-Patalas sampler (lakes), sterile corers (soil), filtration apparatus (water) [1] [6]. |

| Calicheamicin | Calicheamicin, MF:C55H74IN3O21S4, MW:1368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mytoxin B | Mytoxin B, MF:C29H36O9, MW:528.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The assembly of microbial communities is rarely governed by a single process. Instead, a dynamic nexus of deterministic and stochastic forces interacts to shape community structure, with the balance shifting predictably across ecosystems, temporal scales, and among different microbial ecotypes. A robust understanding of these assembly rules, enabled by the integrated use of high-throughput sequencing, null modeling, and neutral theory, is paramount. This knowledge not only deepens fundamental ecological understanding but also enhances our ability to predict microbial community responses to environmental changes, manage ecosystem health, and eventually engineer microbial communities for industrial and therapeutic applications.

Understanding the forces that shape biological communities, particularly microbial communities, is a fundamental pursuit in ecology with significant implications for drug development and therapeutic interventions. Two primary theoretical frameworks have emerged to explain community assembly: niche theory and neutral theory. Niche theory posits that community structure is determined by deterministic factors such as environmental filtering and species interactions, where each species possesses a unique set of traits adapted to specific environmental conditions [9] [10]. In contrast, neutral theory suggests that community structure is primarily shaped by stochastic processes like birth, death, dispersal, and ecological drift, assuming functional equivalence among individuals of different species [9] [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these frameworks, focusing on their application in microbial community research, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Principles

Core Principles of Niche Theory

Niche theory provides a deterministic framework for understanding community assembly. Its core principles include:

- Environmental Filtering: Species persist only in environments where their physiological and behavioral adaptations allow them to meet fitness requirements [9] [10].

- Resource Partitioning: Coexistence is facilitated by differential resource use among species, reducing direct competition [9].

- Niche Differentiation: Evolution drives species to occupy distinct ecological niches, minimizing competition [9].

- Individualized Niches: Recent expansions of niche theory recognize that individual organisms can alter their niches through three primary mechanisms: niche construction (modifying the environment), niche choice (selecting environments), and niche conformance (phenotypic adjustment to the environment) [12].

Core Principles of Neutral Theory

Neutral theory offers a contrasting perspective based on stochastic dynamics:

- Functional Equivalence: The theory assumes that trophically similar individuals are ecologically equivalent in birth, death, dispersal, and speciation rates [9] [10].

- Ecological Drift: Community composition changes randomly over time through probabilistic immigration, extinction, and speciation events [9] [11].

- Dispersal Limitation: Geographic distance and physical barriers limit species movement, creating spatially structured communities [13].

- Neutral Variation: Even genotypically identical individuals exhibit substantial variation in fitness components (lifespan, reproductive success) due to stochastic events during life courses [11].

Table 1: Fundamental Contrasts Between Niche and Neutral Theories

| Aspect | Niche Theory | Neutral Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Primary processes | Deterministic (environmental filtering, species interactions) | Stochastic (ecological drift, dispersal limitation) |

| Species differences | Fundamental to community assembly | Considered irrelevant to community patterns |

| Key predictors | Environmental conditions, functional traits | Abundance, dispersal ability, speciation rate |

| Temporal dynamics | Predictable succession based on environmental conditions | Unpredictable fluctuations based on demographic stochasticity |

| Metacommunity context | Species-sorting perspective | Island biogeography perspective |

Philosophical Frameworks: Realism versus Instrumentalism

The debate between these theories often reflects deeper philosophical perspectives. Niche theory typically aligns with realism, emphasizing detailed, mechanistic explanations based on known biological processes. Neutral theory often aligns with instrumentalism, prioritizing predictive power and generality over mechanistic detail [9] [10]. Rather than being mutually exclusive, these perspectives represent complementary approaches to understanding complex ecological systems, with each having utility for different research questions and scales of analysis [10].

Diagram 1: Theoretical frameworks of community assembly. NC3 mechanisms represent individualized niche processes [12].

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Frameworks

Molecular Techniques for Community Analysis

Advanced molecular techniques enable researchers to characterize microbial communities with unprecedented resolution:

- 16S and 18S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing: Standard approach for profiling bacterial and micro-eukaryotic communities, respectively. Targets hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4 for 16S, V4 for 18S) to determine taxonomic composition [13].

- Quantitative Sequencing Frameworks: Methods like digital PCR (dPCR) anchoring transform relative abundance data to absolute quantification, addressing limitations of relative abundance analyses [14].

- Metagenomic, Metatranscriptomic, and Metabolomic Analyses: Provide functional insights into community metabolic potential, gene expression, and metabolic activities [15].

Analyzing Community Assembly Processes

Researchers employ specific analytical frameworks to quantify the relative influence of niche and neutral processes:

- βNTI (β Nearest-Taxon Index) and RCBray (Modified Raup-Crick Index): Statistical measures to evaluate the impact of stochastic and deterministic processes on community assembly [13].

- Neutral Community Model (NCM): Quantifies the influence of stochastic processes in shaping microbial communities [13].

- Co-occurrence Network Analysis: Reveals coexistence patterns through correlation analysis (e.g., Spearman correlation coefficients) and identifies keystone taxa based on topological roles [13].

Qualitative Assessment of Microbial Interactions

Direct experimental observation of microbial interactions provides crucial validation for theoretical predictions:

- Co-culturing Systems: Allow observation of direct cell-cell interactions and directionality of effects [15].

- Morphological and Spatial Analyses: Techniques including fluorescence microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) visualize physical interactions and spatial organization [15].

- Metabolite Exchange Profiling: Identifies cross-fed metabolites, signaling molecules, and inhibitory compounds through approaches like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [15].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Community Assembly Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit | Microbial community DNA extraction | DNA extraction from water filters and soil samples [13] |

| 338/806R & 528F/706R Primers | Amplification of 16S & 18S rRNA genes | Target V3-V4 (16S) and V4 (18S) regions for sequencing [13] |

| AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit | Purification of PCR products | Post-amplification cleanup before sequencing [13] |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Reagents | Absolute quantification of microbial loads | Converting relative to absolute abundance measurements [14] |

| Fluorescence Labels | Visualizing microbial interactions | Co-localization studies in biofilm and co-culture systems [15] |

Case Study: Urban River Microbial Communities

Experimental Design and Methodology

A comprehensive study of the Xiangjianghe River (XJH) illustrates the integrated application of niche and neutral theory frameworks:

- Sampling Strategy: 84 surface water samples collected from seven sites across four seasons (spring, summer, autumn, winter) with three replicates per site [13].

- Environmental Parameter Measurement: In situ measurement of water temperature (WT), pH, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), dissolved oxygen (DO), and electrical conductivity (EC) using YSI Professional Plus meter [13].

- Water Chemistry Analysis: Determination of total nitrogen (TN) by UV spectrophotometry, total phosphorus (TP) by ammonium molybdate spectrophotometry, and chemical oxygen demand (CODMn) by potassium permanganate titration [13].

- Molecular Analysis: DNA extraction from 0.22μm filters, PCR amplification of target regions, Illumina MiSeq sequencing, and bioinformatic processing using UPARSE algorithm with 97% similarity cutoff for OTU clustering [13].

Quantitative Results and Interpretation

The urban river study generated key quantitative findings regarding community assembly processes:

Table 3: Experimental Findings from Urban River Microbial Community Study [13]

| Parameter | Bacterial Communities | Micro-eukaryotic Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant assembly process | Stochastic (dispersal limitation) | Stochastic (dispersal limitation) |

| Seasonal variation | Significant spatial and temporal variation | Significant spatial and temporal variation |

| Key environmental drivers | Water temperature (WT), oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) | Water temperature (WT), oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) |

| Niche breadth | Relatively wider | Relatively narrower |

| Deterministic processes | Lower proportion | Higher proportion |

| Network complexity | Varied significantly across seasons | Varied significantly across seasons |

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for microbial community assembly study [13].

Implications for Community Ecology

This case study demonstrates several important principles for understanding microbial community assembly:

- Differential Responses: Bacterial and micro-eukaryotic communities in the same environment responded differently to similar environmental drivers, with micro-eukaryotes showing relatively narrower niche breadth and higher sensitivity to deterministic processes [13].

- Seasonal Dynamics: The relative influence of different assembly processes varied significantly across seasons, highlighting the importance of temporal scale in community studies [13].

- Complementary Theories: Both stochastic (neutral) and deterministic (niche) processes contributed to community assembly, supporting an integrated perspective [13].

Comparative Analysis and Integration

Relative Strengths and Limitations

Each theoretical framework offers distinct advantages for understanding community assembly:

- Niche Theory Strengths: Explains species coexistence through resource partitioning, predicts community responses to environmental change, and accounts for functional traits and adaptations [9] [10].

- Niche Theory Limitations: Requires detailed species-specific data, may overestimate competitive exclusion, and struggles to explain high diversity in homogeneous environments [9].

- Neutral Theory Strengths: Predicts species abundance distributions and diversity patterns with few parameters, explains dispersal limitation effects, and serves as valuable null model [9] [10].

- Neutral Theory Limitations: Assumes biologically unrealistic species equivalence, cannot predict specific community composition, and ignores documented niche differences [9].

Integrated Framework for Microbial Community Analysis

Contemporary community ecology recognizes that both niche and neutral processes operate simultaneously in most systems:

- Context Dependence: The relative importance of each process varies across environments, spatial scales, and taxonomic groups [13] [10].

- Process Reconciliation: Modern approaches aim to integrate both perspectives, recognizing that communities are influenced by both stochastic drift and deterministic selection [9] [10].

- Hierarchical Filtering: A synthetic framework proposes that environmental filters first determine which species can persist (niche processes), followed by stochastic assembly within these constraints (neutral processes) [13].

Applications in Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

Understanding community assembly principles has profound implications for microbiome-based therapeutics:

- Microbiome Engineering: Niche theory principles guide the design of microbial consortia with stable coexistence properties based on resource partitioning and complementary niches [16].

- Infection Control: Understanding neutral processes helps predict pathogen dynamics and emergence in clinical settings, particularly for opportunistic infections [15].

- Therapeutic Development: Microbial interaction networks identified through co-occurrence analysis reveal potential targets for manipulating community composition [13] [15].

- Personalized Medicine: Individualized niche concepts inform development of patient-specific microbiome therapies based on host-specific environmental conditions [12].

The continuing dialogue between niche and neutral perspectives reflects the dynamic nature of ecological science, where multiple complementary models provide deeper insights than any single theoretical framework alone [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated approach offers the most promising path toward understanding and manipulating microbial communities for therapeutic benefit.

In microbial ecology, interactions between microorganisms are fundamental drivers of community structure, function, and stability. These relationships can be generalized using network theory, a mathematical framework that describes relationships between discrete entities [17]. In a microbial interaction network, nodes represent microbial species or operational taxonomic units (OTUs), while edges denote functional interactions between them [17]. Understanding these interactions is crucial for deciphering the complex dynamics of microbial communities and their contributions to host health in various environments [17] [18].

The characterization of these interaction networks enhances our understanding of the systems dynamics of microbiomes, potentially leading to more precise therapeutic strategies for managing microbiome-associated diseases [17]. However, due to unique characteristics of microbiome data—including high dimensionality, compositional nature, and sparsity—detecting ecological interaction networks remains a considerable challenge and an active field of methodological development [17] [19].

Defining Key Microbial Interactions

Microbial interactions are typically classified by the net effect that each microorganism has on its partner's growth rate, characterized by both the sign (positive, negative, or neutral) and magnitude (strong or weak) of the interaction [17]. The bidirectional ecological relationship between two microbes (A and B) can be described using a coordinate pair (x, y), where x represents the net effect of microorganism A on B, and y represents the net effect of B on A [17]. This framework analogizes five fundamental ecological interaction mechanisms.

Table 1: Classification of Key Microbial Interactions

| Interaction Type | Effect of A on B | Effect of B on A | Ecological Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | + (Positive) | + (Positive) | Both microorganisms benefit from the interaction |

| Commensalism | + (Positive) | 0 (Neutral) | One benefits while the other is unaffected |

| Competition | - (Negative) | - (Negative) | Both negatively affect each other |

| Amensalism | 0 (Neutral) | - (Negative) | One is harmed while the other is unaffected |

| Exploitation (Parasitism/Predation) | + (Positive) | - (Negative) | One benefits at the expense of the other |

Network Representation of Interactions

Networks can be further characterized by their mathematical properties [17]:

- Weighted networks: Quantify the strength or magnitude of interactions

- Signed networks: Incorporate both positive and negative values

- Directed networks: Specify source and target (cause and effect) relationships

Only directed, weighted, and signed networks can fully describe all five forms of ecological interactions, as they capture both the direction and nature of the effects between microbial partners [17].

Methodological Comparison for Detecting Microbial Interactions

Researchers employ diverse methodological approaches to detect and characterize microbial interactions, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications.

Statistical Inference from Sequencing Data

Statistical methods for inferring microbial interactions from sequencing data can be broadly categorized by their underlying experimental design and analytical approach [17].

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Microbial Interaction Detection

| Method Category | Subtype | Key Features | Network Type Inferred | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional Analysis | Correlation-based | Measures association patterns from snapshot data | Undirected, signed, weighted | Cannot infer causality; sensitive to compositionality |

| Parametric | Assumes adherence to specific statistical models | Undirected | Model misspecification risk | |

| Non-parametric | No assumption of specific distribution | Undirected | May require larger sample sizes | |

| Longitudinal Analysis | Time-series inference | Uses temporal data to infer causal relationships | Directed, signed, weighted | Requires intensive sampling over time |

| Experimental Validation | Pairwise co-culture | Direct experimental measurement of interactions | Directed, signed, weighted | Limited scalability; culturability challenges |

Cross-sectional methods, which analyze static snapshots of multiple individuals, can infer undirected, weighted interaction networks that indicate positive or negative associations but not causal relationships [17]. The simplest approach calculates correlation between microbial abundances, though the compositional nature of microbiome data presents significant statistical challenges [17].

Longitudinal approaches utilizing time-series data can potentially infer directed networks that clarify ecological mechanisms and causal relationships [17] [20]. These methods track how microbial abundances change over time, allowing researchers to infer which species are influencing others.

Experimental Co-culture Approaches

Experimental validation remains crucial for confirming statistically inferred interactions. Recent large-scale co-culture studies have provided valuable insights into interaction patterns. The "PairInteraX" dataset represents a significant advancement, systematically investigating pairwise interactions of 113 bacterial strains isolated from healthy human guts [18].

This comprehensive experimental approach revealed that negative interactions predominated among human gut bacteria, with competition being particularly common [18]. When integrated with metagenomic abundance data, researchers observed that species engaged in negative interactions—especially competitive ones—tended to exhibit higher in vivo abundance and co-occurrence frequencies [18].

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Interaction Studies

Large-scale Pairwise Co-culture Protocol

The PairInteraX study established a robust protocol for systematically characterizing pairwise bacterial interactions [18]:

Bacterial Strain Selection:

- Select strains based on abundance coverage and functional representation of target microbiome

- Confirm strain identities using full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Evaluate taxonomic diversity and include species of high research interest

Monoculture Preparation:

- Inoculate 1% (v/v) bacterial suspensions into 5 mL modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium (mGAM)

- Incubate at 37°C for 72-96 hours under anaerobic conditions (85% N₂, 5% CO₂, 10% H₂)

- Harvest bacterial cells via centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C

- Resuspend in mGAM medium adjusted to OD₆₀₀ = 0.5

Pairwise Co-culture Setup:

- Pipette 2.5 μL of first isolate culture onto mGAM agar plate surface

- Add 2.5 μL of second bacterial isolate at external tangency to the first

- Incubate for 72 hours at 37°C under anaerobic conditions

- Record interaction results using stereo microscopy with digital camera

Interaction Assessment:

- Classify interactions based on growth patterns compared to monocontrols

- Categories: neutralism (0/0), commensalism (0/+), exploitation (-/+), amensalism (0/-), competition (-/-)

- Perform image preprocessing and segmentation to enhance clarity

- Use threshold segmentation for quantitative assessment

Computational Analysis Pipeline

For researchers analyzing sequencing data, a standardized bioinformatics pipeline is essential [21]:

Data Preparation:

- Import feature tables, annotation files, sample metadata, phylogenetic trees, and representative sequences

- Perform data cleaning, filtering, and normalization

- Address compositionality and sparsity issues inherent to microbiome data

Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate alpha and beta diversity indices

- Perform differential abundance testing

- Construct correlation networks using appropriate measures (SparCC, SPIEC-EASI, etc.)

- Apply multiple testing corrections to control false discovery rates

Network Analysis:

- Identify keystone taxa using within-module connectivity (Zi) and among-module connectivity (Pi)

- Calculate network topology parameters (modularity, connectivity, etc.)

- Visualize networks using Cytoscape or R packages

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Microbial Interaction Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Application in Interaction Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Media | Modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium (mGAM) | Supports diverse gut microbiota; maintains community structure [18] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit | Efficient microbial DNA extraction from complex samples [13] [22] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq | 16S/18S rRNA amplicon sequencing for community profiling [13] |

| Primer Sets | 338F/806R (16S V3-V4), ITS1/ITS2 (fungal ITS) | Target amplification for bacterial and fungal communities [13] [22] |

| Analysis Software | QIIME 2, Mothur, USEARCH | Processing raw sequencing data; OTU/ASV picking [21] |

| Statistical Environment | R Language and Environment | Data analysis, visualization, and statistical testing [19] [21] |

| R Packages | phyloseq, microeco, amplicon | Integrated microbiome data analysis [21] |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape, Gephi | Visualization and analysis of microbial interaction networks [13] [18] |

| Anaerobic Systems | Anaerobic chambers (85% Nâ‚‚, 5% COâ‚‚, 10% Hâ‚‚) | Maintaining proper conditions for obligate anaerobes [18] |

| VO-Ohpic trihydrate | VO-Ohpic trihydrate, MF:C12H17N2O10V, MW:400.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NFAT Inhibitor-2 | NFAT Inhibitor-2, MF:C22H20F2N2O4S, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion and Future Directions

Understanding microbial interactions through multiple methodological approaches provides complementary insights into community assembly and dynamics. While statistical inference from sequencing data can reveal broad patterns of association, experimental validation remains crucial for establishing causal relationships and mechanisms [17] [18].

Recent studies highlight that negative interactions, particularly competition, may be more prevalent in certain environments like the human gut than previously recognized [18]. The PairInteraX dataset demonstrated that as microbial abundances increase, mutualism diminishes while competition increases, suggesting that maintaining community diversity requires a balance of various interaction types [18].

Methodologically, the field is moving toward ensemble approaches that combine multiple analytical techniques to overcome the limitations of individual methods [17] [20]. This is particularly important given that different community assembly assessment methods can yield varying results, as demonstrated in bioreactor studies where neutral modeling showed 32-90% stochastic influence depending on the system [20].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Integrating multi-omic data to understand molecular mechanisms underlying interactions

- Developing more sophisticated computational models that better represent microbial ecology

- Standardizing experimental protocols to enable cross-study comparisons

- Expanding interaction studies beyond pairwise relationships to higher-order interactions

As methodological frameworks continue to mature, our ability to precisely map and manipulate microbial interactomes will undoubtedly advance, facilitating the development of novel therapeutic strategies for microbiome-associated diseases and the optimization of microbial communities in engineered systems [17].

Impact of Environmental Filters on Community Assembly

Environmental filtering is a fundamental deterministic process that shapes the assembly of microbial communities by selecting for taxa possessing traits that enable survival and proliferation under specific environmental conditions [23]. This process plays a pivotal role in structuring communities across diverse habitats, from human-associated microbiomes to aquatic ecosystems [24] [23]. The concept operates on the principle that environmental conditions create a selective screen—or "filter"—that permits only certain species with appropriate physiological adaptations to establish within a given habitat. Understanding environmental filters is crucial for predicting community responses to perturbation, designing synthetic communities with desired functions, and developing therapeutic interventions targeting microbial assemblages [24] [25].

The assembly of any microbial community is governed by the interplay of both deterministic (including environmental filtering and species interactions) and stochastic processes (such as ecological drift and dispersal limitation) [24] [23]. Environmental filtering represents a key deterministic mechanism wherein abiotic factors—including pH, temperature, oxygen availability, and nutrient composition—selectively exclude maladapted taxa while favoring those with traits conferring fitness advantages under prevailing conditions [23]. This review systematically compares methodological approaches for investigating environmental filters, provides experimental protocols for quantifying their effects, and synthesizes key findings across diverse microbial systems to establish a standardized framework for community assembly research.

Comparative Analysis of Research Approaches

Methodological Frameworks for Studying Assembly Processes

Researchers employ distinct methodological approaches to disentangle the effects of environmental filtering from other assembly processes, each with characteristic strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications. The choice of methodology significantly influences the scale, resolution, and mechanistic insights achievable in community assembly studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Research Approaches for Studying Environmental Filters

| Approach | Core Methodology | Key Strengths | Major Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Field Studies | Sampling natural communities across environmental gradients; statistical correlation of community composition with environmental parameters [23] | Captures real-world complexity; identifies natural co-variation patterns; reveals in situ relationships | Limited causal inference; confounding variables; difficulty isolating individual filters [24] | Identifying environmental correlates of community composition in black-odor waters [23] |

| Bottom-Up Synthetic Communities | Constructing defined microbial consortia with known composition; testing establishment under controlled conditions [26] | High reproducibility; precise control of community composition; enables causal inference; reveals mechanistic insights [26] | Simplified systems may lack ecological realism; challenging to scale to high complexity [26] | Testing priority effects using defined strains in gnotobiotic mice [24] |

| Top-Down Manipulative Experiments | Perturbing natural communities with specific environmental changes; tracking compositional responses [24] | Maintains natural complexity while testing specific factors; reveals responses of intact communities | Complex interactions can obscure mechanisms; difficult to attribute effects to specific causes [24] | Nutrient manipulation experiments in black-odor water systems [23] |

| Integrated Hybrid Approaches | Combining observational data with controlled experimentation under identical conditions [24] | Links patterns with processes; validates theoretical predictions; bridges different methodological strengths | Resource-intensive; requires specialized expertise in multiple techniques | Resolving ecological drift through flow cytometry combined with mathematical modeling [24] |

Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Environmental Filtering

The contribution of environmental filtering to community assembly is quantified using specialized statistical metrics that measure how much of community variation is explained by environmental factors versus spatial or random effects.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Environmental Filters in Community Assembly

| Analytical Method | Measured Parameters | Interpretation | Data Requirements | Implementation Tools | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null Deviation Analysis | Deviation of observed communities from null expectation; β-nearest taxon index (βNTI) [23] | βNTI | > 2 indicates homogeneous selection; | βNTI | < 2 suggests stochastic dominance | Phylogenetic tree; community composition data; environmental data | R packages: picante, PhyloMeasures | |

| Variation Partitioning | Proportion of community variance explained by pure environmental, pure spatial, and shared effects [23] | Higher pure environmental fraction indicates stronger environmental filtering | Community composition matrix; environmental parameter matrix; spatial coordinates | R packages: vegan, adespatial | ||||

| Mantel Tests | Correlation between community dissimilarity and environmental distance matrices [23] | Significant positive correlation indicates environmental filtering structures communities | Pairwise community dissimilarity matrix; pairwise environmental distance matrix | R packages: vegan, ecodist | ||||

| Generalized Linear Models | Coefficients for environmental predictors of species abundances or community metrics [27] | Significant coefficients indicate specific environmental filters influencing populations | Species abundance data; environmental measurements | R, Python, SPSS with appropriate packages |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Field Sampling and Environmental Characterization

This protocol establishes standardized procedures for investigating environmental filters in natural ecosystems, using black-odor water systems as a representative example [23].

Materials and Reagents:

- Sterile sampling containers (varying volumes for different analyses)

- Multiparameter water quality sonde (for DO, pH, temperature, conductivity)

- Water filtration apparatus with 0.22μm membranes

- Reagents for nutrient analysis (TOC, NHâ‚„âº-N, NO₃â»-N, PO₄³â»-P)

- Chlorophyll a extraction solvents (acetone, methanol) and fluorometer

- DNA extraction kit (specific for environmental samples)

- PCR reagents and primers for 16S rRNA gene amplification

Procedure:

- Site Selection and Replication: Select sampling sites representing the environmental gradient of interest. Include sufficient biological replicates (minimum n=3 per site) and appropriate spatial sampling design to account for microheterogeneity [23].

- In Situ Measurements: Using a calibrated multiparameter sonde, record dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, temperature, and conductivity at each sampling point at consistent depths. Note that in black-odor water studies, DO concentrations typically range from 0.15 to 5.24 mg/L, representing hypoxic to anoxic conditions [23].

- Water Collection: Collect water samples using appropriate samplers (e.g., Van Dorn or Niskin bottles) at predetermined depths. Transfer to sterile containers, preserving some samples unaltered and processing others immediately for filtration.

- Filtration and Preservation: Filter appropriate water volumes (typically 100-1000 mL depending on microbial biomass) through 0.22μm membranes. Divide filters for subsequent molecular analysis (flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen) and chemical characterization (store at -80°C).

- Nutrient Analysis: Analyze filtered water for total organic carbon (TOC) using combustion catalytic oxidation, ammonium nitrogen (NHâ‚„âº-N) via spectrophotometric methods, and other relevant nutrients using standard limnological methods [23].

- Chlorophyll a Quantification: Filter additional water volumes for chlorophyll a analysis, extract pigments in 90% acetone, and measure fluorescence to estimate algal biomass [23].

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract genomic DNA from filters using specialized kits for environmental samples. Amplify the 16S rRNA gene V4 region using barcoded primers and perform high-throughput sequencing on Illumina platforms. Sequence depth should exceed 50,000 reads per sample to adequately capture diversity [23].

Protocol 2: Synthetic Community Construction and Testing

This protocol details the bottom-up construction of synthetic microbial communities to test specific hypotheses about environmental filters under controlled laboratory conditions [26].

Materials and Reagents:

- Pure culture isolates representing functional groups of interest

- Selective and non-selective culture media

- Anaerobic chamber for oxygen-sensitive microbes

- Flow cytometry equipment for cell counting and sorting

- Microtiter plates or bioreactors for community cultivation

- Metabolite analysis platforms (HPLC, GC-MS)

- Disease-mimicking culture media (e.g., Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Medium [SCFM2]) [25]

Procedure:

- Strain Selection: Select bacterial strains based on functional characteristics, phylogenetic diversity, or known interactions. For gut microbiome studies, the Oligo-Mouse-Microbiota (OMM12) consortium provides a standardized model with 12 bacterial species [25].

- Individual Culture Preparation: Grow each strain individually in appropriate medium under optimal conditions. Monitor growth to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5-0.8) unless otherwise required.

- Community Assembly: Combine strains in predetermined proportions. Initial inoculum ratios can be equal or weighted based on natural relative abundances. Total starting density typically ranges from 10âµ to 10â· cells/mL depending on vessel size and growth conditions.

- Environmental Manipulation: Apply specific environmental filters by cultivating communities under different conditions (e.g., varying oxygen availability, pH, nutrient composition, or antimicrobial presence). For pathogen studies, use disease-mimicking media like synthetic cystic fibrosis medium (SCFM2) to replicate in vivo conditions [25].

- Temporal Monitoring: Sample communities at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 hours) to track compositional dynamics. Preserve samples for DNA extraction, metabolite profiling, and microscopic examination.

- Compositional Assessment: Extract community DNA and perform strain-specific quantification using qPCR with designed primers or amplicon sequencing with strain-discriminatory resolution.

- Functional Measurements: Quantify metabolic outputs relevant to the environmental filter being tested (e.g., sulfide production for sulfate-reducing bacteria, antibiotic tolerance in polymicrobial communities) [25].

- Data Integration: Correlate compositional changes with environmental parameters and functional outputs to identify strain-specific responses to environmental filters.

Key Research Findings and Data Synthesis

Environmental Filters in Aquatic Systems

Research on black-odor water systems provides compelling evidence for environmental filtering under extreme conditions. These systems develop due to microbial processes in heavily polluted, hypoxic waters where specific environmental factors strongly filter community composition.

Table 3: Environmental Filters Identified in Black-Odor Water Systems [23]

| Environmental Factor | Experimental Range | Impact on Community Composition | Key Taxa Selected | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | 0.15 - 5.24 mg/L | Strongest filter; explains up to 40.2% of community variation | Desulfobacterota, Geobacter spp. | Increased sulfate reduction; metal sulfide formation |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | 5.28 - 18.55 mg/L | Significant filter (26.8% explanation); shapes functional potential | Fermentative bacteria, hydrolytic organisms | Enhanced organic matter degradation; oxygen consumption |

| Ammonium Nitrogen (NHâ‚„âº-N) | Up to 8.62 mg/L | Moderate filter (18.5% explanation); influences nitrogen cyclers | Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, nitrifiers | Altered nitrogen transformation pathways |

| Chlorophyll a (Algal Biomass) | Variable based on productivity | Indirect filter via organic matter input and oxygen production | Cyanobacteria, algal-associated bacteria | Primary production; daytime oxygen supersaturation |

In controlled sediment-water column experiments mimicking black-odor conditions, the relative influence of deterministic processes (primarily environmental filtering) increased from 52.3% to 73.8% as organic pollution intensified, demonstrating how environmental stress amplifies filtering strength [23]. Microbial source tracking analysis further indicated that 56.7 ± 3.2% of the community in severely polluted sites originated from livestock breeding sewage, highlighting how environmental conditions filter input communities to shape the established assemblage [23].

Environmental Filters in Host-Associated Systems

In host-associated environments, environmental filtering operates through host-specific factors including diet, genetics, immunity, and medication use [24]. The gastrointestinal tract represents a strongly filtered environment where pH, bile salts, antimicrobial peptides, and nutrient availability sequentially select for progressively specialized communities along the gastrointestinal gradient.

Table 4: Environmental Filters in Host-Associated Microbial Communities

| Filter Type | Specific Parameters | Community Effects | Methodological Approaches | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Components | Fiber content, fat composition, specific nutrients [24] | Alters substrate availability; selects for specialized degraders | Gnotobiotic mice; defined diets; metabolic profiling | Rapid community shifts within 24 hours of dietary change |

| Medication Exposure | Antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, other drugs [24] | Direct inhibition; creates open niches for resistant taxa | Longitudinal sampling; invasion experiments | Antibiotic perturbation increases susceptibility to pathogen colonization |

| Host Genetics | Immune recognition genes, mucosal properties [24] | Shapes host-mediated selection pressure | Inbred mouse strains; human twin studies | Specific gene variants correlate with taxon abundances |

| Microbial Interactions | Priority effects, cross-feeding, inhibition [24] | Historical contingency affects establishment | Controlled colonization sequences; metabolic modeling | Early colonizers can pre-empt niches and create alternative stable states |

Host-associated environments demonstrate how environmental filtering interacts with priority effects, where early colonizing species can modify the environment (e.g., through oxygen depletion or metabolite production) to create additional filters that affect subsequent community assembly [24]. Studies in gnotobiotic mouse models have shown that niche overlap and phylogenetic relatedness amplify these priority effects, with early-arriving species pre-empting niches for phylogenetically similar competitors [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Environmental Filter Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit, MagAttract PowerSoil DNA Kit | Environmental DNA isolation; inhibitor removal | Critical for diverse sample types; standardized protocols enable cross-study comparisons |

| Sequencing Primers | 515F/806R for 16S rRNA V4 region, strain-specific primers | Target gene amplification; community profiling | Choice of primer set influences taxonomic resolution and amplification bias |

| Specialized Culture Media | Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Medium (SCFM2), Artificial Urine Medium (AUM) [25] | Replicate in vivo conditions during in vitro experiments | Disease-mimicking media reveal community phenotypes absent in rich media |

| Metabolic Probes | Resazurin (redox indicator), pH-sensitive fluorescent dyes | Monitor microbial activity and environmental conditions | Enable real-time tracking of community function without destructive sampling |

| Isotopic Tracers | ¹³C-labeled substrates, ¹âµN-ammonium | Track nutrient flows in microbial networks | Identify cross-feeding relationships and metabolic niches |

| Cell Sorting Reagents | Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) probes, viability stains | Population-specific isolation and quantification | Enable tracking of specific taxa within complex communities |

| NH2-Peg4-dota | NH2-Peg4-dota, MF:C26H50N6O11, MW:622.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Chicanine | Chicanine, CAS:627875-49-4, MF:C20H22O5, MW:342.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Environmental filtering represents a fundamental deterministic process governing microbial community assembly across diverse ecosystems. The integration of observational approaches with controlled experimentation provides the most powerful framework for disentangling the effects of environmental filters from other assembly processes [24]. Current evidence demonstrates that filter strength varies substantially across environments, with extreme conditions (e.g., hypoxia in black-odor waters, antibiotic exposure in host environments) typically increasing the relative importance of deterministic selection [24] [23].

Future research priorities include developing higher-resolution techniques for tracking strain-level dynamics, as subspecies variation can significantly influence environmental filtering outcomes [24]. Additionally, integrating temporal sampling with advanced modeling approaches will enhance predictive understanding of how environmental filters shape community trajectories under changing conditions. The systematic application of standardized protocols, such as those presented herein, will enable meaningful cross-system comparisons and accelerate progress in microbial community ecology. As methodological capabilities advance, particularly in synthetic community construction and multi-omics integration, researchers will increasingly move from pattern description to mechanistic prediction and targeted manipulation of environmentally filtered communities for biomedical, biotechnological, and environmental applications.

Understanding microbial community assembly processes is fundamental to microbial ecology and has significant implications for environmental management and restoration. This case study investigates the assembly dynamics within a specific agricultural ecosystem: a paddy field under long-term pesticide pressure. We compare the microbial communities in pesticide-managed plots against non-pesticide controls, focusing on the distinct responses of generalist and specialist subcommunities. The findings provide a framework for comparing how deterministic versus stochastic processes govern microbial communities under pollution stress, a core interest in the broader thesis of microbial community assembly methods research.

Experimental Protocol & Methodology

Site Description and Sample Collection

The field experiment was located in Qianjiang, Hubei province, China, and had been managed for 8 years under two distinct regimes [28] [29]:

- HP (Long-term pesticide exposure): Pesticides (chlorantraniliprole and tebuconazole) were applied following local practices.

- HH (Non-pesticide control): No pesticide application.

Soil samples were collected in 2024 from the top layer using a five-point sampling method. They were immediately transported on dry ice and stored at -80°C prior to analysis. Initial soil analysis confirmed the presence of pesticide residues (0.19 mg/kg chlorantraniliprole and 0.45 mg/kg tebuconazole) in the HP treatment, which were undetectable in the HH treatment [29].

Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics

- DNA Extraction: High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of fresh soil samples using the OMEGA Soil DNA Kit [29].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: The 16S rRNA gene (for bacteria) and the ITS region (for fungi) were amplified and sequenced on an Illumina platform [28] [29].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Sequences were processed using QIIME2, including quality filtering, denoising with DADA2, and taxonomic assignment against reference databases (e.g., SILVA) [30].

- Functional Prediction: Microbial metabolic functions were predicted using the FAPROTAX database [28] [29].

- Network Analysis: Co-occurrence networks were constructed to infer microbial interactions. Key metrics like node degree and closeness centrality were calculated to assess network complexity and stability [28] [31].

- Community Assembly Analysis: Neutral community models and null model analysis were used to quantify the relative contributions of deterministic (e.g., selection) and stochastic (e.g., dispersal limitation, drift) processes in community assembly [28] [32].

The workflow below summarizes the experimental and analytical process.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Community Assembly

Diversity, Composition, and Functional Capacity

The analysis revealed significant differences in microbial community structure and function between the pesticide-exposed (HP) and control (HH) soils.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microbial Community Structure and Function

| Parameter | HP (Pesticide) | HH (Control) | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Diversity | Lower diversity in both specialists and generalists [28] | Higher diversity in both specialists and generalists [28] | Pesticides reduce niche availability and suppress sensitive taxa. |

| Fungal Diversity | Lower diversity in generalists [28] | Higher diversity in generalists [28] | Fungal generalists are particularly vulnerable to pesticide application. |

| Community Composition | Increase in copiotrophs (e.g., Gemmatimonadota); Decrease in oligotrophs (e.g., Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota); Increase in pathogenic Fusarium [28] | Balanced composition; Dominance of oligotrophic phyla [28] | Shift towards fast-growing, potentially metal-tolerant taxa; Higher plant disease risk in HP. |

| Network Complexity | Lower node degree and closeness centrality [28] | Higher node degree and closeness centrality [28] | Less interconnected, fragile microbial network under pesticide stress. |

| Functional Capacity | Reduction in N-cycle and cellulolysis genes; Increase in human disease-related genes [28] [29] | Robust nutrient cycling potential [28] | Ecosystem functions like decomposition and nutrient supply are compromised in HP. |

Assembly Processes: Deterministic vs. Stochastic

A key comparison lies in the ecological processes governing how microbial communities are assembled in each environment.

Table 2: Dominant Microbial Community Assembly Processes

| Ecological Process | HP (Pesticide) | HH (Control) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic Processes | Strongly Dominant [28] | Less prominent [28] | Pesticide application acts as a strong environmental filter, selectively allowing only tolerant species to survive. |

| Stochastic Processes | Weakened [28] | More influential [28] | Random birth, death, and dispersal events play a smaller role when strong selection pressure exists. |

| Impact on Specialists | Homogenizing selection; High vulnerability due to narrow niches [28] | Less constrained | Specialists, with their specific resource needs, are disproportionately filtered out by pesticide stress. |

The following diagram conceptualizes how pesticide pressure influences these assembly processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key reagents and kits used in the featured experiment, which are essential for replicating this type of research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Microbial Community Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Study |

|---|---|---|

| Soil DNA Extraction Kit | Extracts high-quality, PCR-ready genomic DNA from complex soil matrices, critical for downstream sequencing. | OMEGA Soil DNA Kit [29] / Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) [32]. |

| 16S rRNA & ITS Primers | Amplify hypervariable regions of bacterial (16S) and fungal (ITS) genes for taxonomic identification via sequencing. | Used for amplicon sequencing of bacterial and fungal communities [28] [29]. |

| Sequencing Standards & Kits | Provide reagents for library preparation and high-throughput sequencing on platforms like Illumina NovaSeq/MiSeq. | Illumina sequencing platforms were used [28] [30]. |

| Functional Prediction Database | Software tool for predicting prokaryotic metabolic functions from 16S rRNA gene sequencing data. | FAPROTAX was used for functional prediction [28] [29]. |

| Reference Databases | Curated databases of annotated gene sequences for taxonomic classification of sequencing reads. | SILVA database was used for 16S rRNA gene analysis [30]. |

| Stat3-IN-35 | Stat3-IN-35, MF:C21H23NO4, MW:353.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mipomersen Sodium | Mipomersen Sodium, CAS:629167-92-6, MF:C230H305N67Na19O122P19S19, MW:7595 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A Toolkit for Building Communities: From Isolation to Synthetic Consortia

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Approaches to Community Construction

The engineering of microbial communities is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, essential for applications ranging from drug development to environmental sustainability. The assembly of these complex communities is primarily guided by two distinct strategies: top-down and bottom-up approaches. A top-down approach involves starting with a complex, native microbial community and applying environmental pressures or perturbations to steer it toward a desired function or structure [33] [34]. Conversely, a bottom-up approach involves the precise design and construction of a community by piecing together well-characterized individual microorganisms, based on known metabolic pathways and potential interactions, to form a synthetic consortium [33] [34]. Within the broader thesis of microbial community assembly methods, this guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental protocols of these two foundational strategies, providing researchers and scientists with the data necessary to inform their experimental design.

Defining the Approaches and Their Core Principles

The Top-Down Approach

In the top-down approach, an overview of the system is first formulated, specifying but not detailing first-level subsystems [33]. This strategy uses selective environmental variables to steer an existing, complex microbial consortium to achieve a target function, such as the production of a specific biomolecule from waste biomass [34]. It is a classical method that leverages ecological principles like natural selection. The initial community's complexity is accepted, and the engineer's role is to manipulate the ecosystem—for instance, by controlling pH, temperature, or substrate availability—to enrich for community members that perform the desired task. This method relies on the inherent functional redundancy and competition within the native community. However, a major challenge is disentangling the complex microbial interactions and exerting precise control over the final community structure and function [34].

The Bottom-Up Approach

The bottom-up approach is characterized by the piecing together of systems to give rise to more complex systems [33]. For microbiome engineering, this means designing synthetic microbial consortia from scratch using prior knowledge of the metabolic pathways and possible interactions among the selected consortium partners [34]. This approach offers a greater degree of control over the composition and function of the consortium for targeted bioprocesses. It often resembles a "seed" model, where beginnings are small but eventually grow in complexity and completeness [33]. The bottom-up approach is ideal for testing hypotheses about specific microbial interactions and for building communities with well-defined division of labor. Nevertheless, challenges remain in optimal assembly methods and ensuring the long-term stability of these constructed consortia [34].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches

| Feature | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Complex, native microbial community [34] | Individual, well-characterized microbes [34] |

| Design Philosophy | Decomposition & selective enrichment [33] [34] | Composition & rational assembly [33] [34] |

| Level of Control | Lower; controls community function indirectly [34] | Higher; direct control over composition [34] |

| Typical Workflow | Apply environmental variables → Enrich desired function → Characterize resulting community | Define function → Select members → Assemble community → Test performance |

| Analogy in Other Fields | Using black boxes to manipulate a system without detailing elementary mechanisms [33] | Object-oriented programming; designing products as pieces later assembled [33] |

| Egfr-IN-150 | Egfr-IN-150, MF:C29H23ClN6O2, MW:523.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Brimarafenib | Brimarafenib, CAS:1643326-82-2, MF:C24H17F3N4O4, MW:482.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Performance and Experimental Data

The performance of top-down and bottom-up approaches can be evaluated based on key metrics such as stability, productivity, and predictability. The following table summarizes experimental findings from various studies, particularly in the context of biomanufacturing from waste biomass.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison for Waste Biomass Valorization

| Performance Metric | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach | Supporting Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Stability | High; resilient to perturbations due to functional redundancy [34] | Can be low; challenges with long-term stability of defined consortia [34] | Studies on anaerobic digestion communities [34] |

| Productivity/Titer | Can be high, but often variable and subject to local optimization [33] [34] | Potentially very high with optimized partners, but not guaranteed [34] | Production of n-caproic acid and other chemicals [34] |

| Predictability & Control | Low; difficult to predict final community structure [34] | High; offers control over composition and intended function [34] | Assembly of synthetic consortia for defined pathways [34] |

| Development Time | Can be faster for process initiation [34] | Can be slower due to need for detailed characterization and assembly [34] | Comparison of lab-scale bioreactor studies [34] |

| Robustness to Contamination | High; native community can be resistant to invasion | Low; defined consortia can be outcompeted by invaders | Inferences from ecological theory and bioprocess engineering [34] |

Beyond biomanufacturing, these approaches are also used to understand natural communities. For example, a study on eutrophic shallow lakes used multivariate analysis to relate bacterial community composition to bottom-up (resources) and top-down (grazing) variables. It found that in turbid lakes, the bacterial community was related to phytoplankton biomass (a bottom-up factor), whereas in clearwater lakes, grazing by ciliates and daphnids (a top-down factor) was a significant driver of community change [35]. Similarly, research in a Norwegian fjord supported the "Killing the Winner" theory, suggesting that viral predation (top-down control) can help maintain bacterial diversity, while the specific community composition is shaped by competition for substrates (bottom-up control) [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To implement these approaches, researchers rely on specific, well-established experimental protocols. The following workflows detail the key methodologies for both top-down and bottom-up strategies.

Protocol for a Top-Down Enrichment Experiment

Objective: To establish a microbial community capable of converting waste biomass (e.g., plant-derived polysaccharides) into a specific valuable product (e.g., organic acids) through selective pressure.

- Inoculum Sourcing: Acquire a complex microbial community from a relevant environment, such as anaerobic sludge from a wastewater treatment plant or soil from a compost site [34].

- Bioreactor Setup: Inoculate the community into a bioreactor containing the waste biomass as the primary carbon source. Use a defined medium that limits other carbon sources to exert selective pressure [34].

- Application of Selective Pressure:

- Maintain strict environmental conditions like pH, temperature, and redox potential to favor the desired metabolic pathway [34].

- In some cases, serial transfer or continuous culture is employed. A small aliquot of the community is periodically transferred to fresh medium with the same substrate, continually enriching for microbes that effectively consume it [37].

- Process Monitoring: Monitor the depletion of the substrate and the production of the target metabolite(s) using analytical methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography (GC).

- Community Characterization: Periodically sample the community for culture-independent analysis. This typically involves:

- DNA Extraction: Using bead-beating methods for thorough cell lysis and kits for DNA purification [35].

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Amplifying the 16S rRNA gene with universal prokaryotic primers (e.g., 357F-GC-clamp and 518R) and analyzing the products via Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE) or high-throughput amplicon sequencing to track changes in community structure over time [35].

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Shotgun sequencing of community DNA to understand the genetic potential and metabolic pathways that have been enriched [37] [34].

- Functional Validation: The enriched community is considered successful if it stably maintains high productivity of the target product over multiple generations or transfers.

Protocol for Bottom-Up Construction of a Synthetic Consortium

Objective: To construct a minimal microbial community where two or more members engage in a syntrophic relationship (e.g., cross-feeding) to perform a complex biotransformation.

- Pathway Deconstruction: Break down the target biotransformation process into its constituent metabolic steps. Identify potential substrate and product exchanges between these steps [34] [38].

- Strain Selection: Select individual microbial strains that are genetically tractable and each capable of performing one or more of the identified steps. Knowledge may come from model gut commensals like Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron or Escherichia coli [37]. Genomic and physiological data are used to ensure metabolic compatibility [34].

- Individual Strain Characterization: Grow each strain in isolation to understand its growth kinetics, substrate preferences, and metabolic outputs under the intended culture conditions [38].

- Consortium Assembly: Co-culture the selected strains in a defined medium. The initial ratio of inoculants may be optimized.

- Interaction Validation: Use techniques like Stable Isotope Probing (SIP) or metabolite profiling to confirm the predicted metabolic interactions and cross-feeding between the consortium members [38].

- Consortium Performance Testing: Measure the overall function of the synthetic consortium (e.g., yield of a final product) and compare it to the performance of individual members or a non-engineered community.

- Modeling and Optimization: Use constraint-based metabolic modeling (e.g., with genome-scale metabolic reconstructions) to predict and optimize the flux distribution within the consortium for improved productivity [34] [38].

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for both the top-down and bottom-up approaches to community construction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of both top-down and bottom-up strategies relies on a suite of essential laboratory reagents, computational tools, and analytical techniques.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Microbial Community Research

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction & Purification | Bead-beating kits, Phenol-chloroform extraction, Wizard purification columns (Promega) [35] | To isolate high-quality, PCR-ready genomic DNA from complex microbial samples or pure cultures. |

| PCR and Molecular Analysis | Primers (e.g., 357F-GC-clamp, 518R for 16S rRNA DGGE [35]), DNA polymerases, DGGE equipment | To amplify and fingerprint microbial communities for diversity analysis and composition tracking. |

| High-Throughput Sequencing | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing (Illumina), Shotgun metagenomic sequencing [37] [39] | To comprehensively profile "who is there" and "what they can do" in a community at high resolution. |

| Computational & Modeling Tools | Genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., for E. coli, B. thetaiotaomicron [37] [38]), Graph Neural Network models for prediction [39] | To integrate data, predict metabolic fluxes, forecast community dynamics, and inform consortium design. |

| Analytical Chemistry | HPLC, GC, Mass Spectrometry | To quantify substrate consumption and product formation (e.g., organic acids, biofuels) in culture supernatants. |

| Stable Isotopes | ¹³C-labeled substrates for Stable Isotope Probing (SIP) [38] | To trace the flow of specific nutrients through different members of a microbial community. |

| Cultivation Systems | Anaerobic chambers, Bioreactors, Chemostats | To maintain controlled environmental conditions (e.g., anoxia, pH, nutrient feed) for community cultivation and enrichment. |

| Minoxidil | Minoxidil, CAS:38304-91-5, MF:C9H15N5O, MW:209.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AMPK activator 16 | AMPK activator 16, MF:C23H20ClNO5S, MW:457.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparison between top-down and bottom-up approaches reveals a clear trade-off between control and robustness. The bottom-up approach offers superior predictability and control, making it ideal for testing mechanistic hypotheses and engineering consortia with precise division of labor [34]. In contrast, the top-down approach often results in communities with higher functional stability and resilience, making it suitable for industrial bioprocessing where environmental conditions may fluctuate [34].

The future of microbial community engineering lies in the integration of these two strategies. A promising direction is to use top-down enrichment to identify key functional players and interactions, which can then be used to inform the rational bottom-up design of more robust synthetic consortia [34]. Furthermore, advancements in metabolic modeling and machine learning, such as graph neural networks for predicting community dynamics, are poised to enhance the predictive power and success of both methodologies [39] [38]. By leveraging the strengths of both approaches, researchers and drug development professionals can more effectively construct microbial communities for advanced biomanufacturing and therapeutic applications.

Core Microbiome Mining for Identifying Key Community Members

The concept of a core microbiome—a set of consistent microbial features across populations—represents a major goal in microbial ecology and human health research [40]. Identifying these key community members is crucial for understanding the stable, beneficial elements of our microbiome and for pinpointing dysbiosis in disease states [40]. The human microbiome is involved in numerous physiological processes including nutrient uptake, pathogen defense, and immune system development, making its core components particularly significant for therapeutic targeting [40]. However, defining this core remains a complex challenge due to high individual variation, diverse methodological approaches, and the multi-faceted nature of microbial communities [40].

This guide objectively compares the predominant computational and statistical methods used for core microbiome mining, evaluating their performance, applicability, and limitations within the broader context of microbial community assembly research. We synthesize experimental data from large-scale benchmark studies to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based recommendations for method selection.

Methodological Approaches to Core Microbiome Definition

The core microbiome can be defined through several conceptual frameworks, each with distinct methodological implications for identifying key community members.

Community Composition Approaches

Community composition definitions search for taxa consistently found across host populations [40]. This approach assumes that core members contribute directly to host health or indirectly through community stability [40]. Keystone species are of particular interest as they play crucial roles in ecological structure despite potentially low abundance [40]. The loss of these species can dramatically alter ecological niches and potentially lead to dysbiosis [40].

Table 1: Approaches for Defining the Core Microbiome

| Approach | Pros | Cons | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Composition | Relatively simple to implement; can be applied to amplicon studies | Common taxa usually identified only at high taxonomic levels | [40] |

| Functional Profile | Captures the core's contribution to host and community | Difficult to distinguish human-specific from broad core functions | [40] |

| Ecology | Captures complex community structure patterns; potentially more realistic | Unclear which patterns should be considered; no standard methods | [40] |

| Stability | Addresses critical characteristics of resistance and resilience | Vague definition; no widely accepted evaluation methods | [40] |

Functional Profile Approaches

Function-based descriptions focus on consistent genes or pathways across populations, acknowledging that multiple species can fill the same niche—a phenomenon known as functional redundancy [40]. This approach recognizes that specific functional capacities rather than particular taxa may constitute the crucial core elements, especially for metabolic functions like complex carbohydrate degradation [40].

Abundance-Occupancy Distributions

Abundance-occupancy distributions, used in macroecology to describe community diversity changes over space, offer an ecological approach for prioritizing core membership in both spatial and temporal studies [41]. When neutral models are fit to these distributions, they can provide insights into deterministically selected core members that are likely selected by the environment [41]. This method enables systematic exploration of core membership and quantification of contributions to beta diversity [41].

Figure 1: Methodological Workflow for Core Microbiome Mining. The diagram illustrates three primary approaches for identifying key community members in microbiome studies, each with distinct analytical methods leading to an integrated core definition.

Comparative Analysis of Classification Methods

Supervised classification analysis represents a powerful approach for identifying discriminative microorganisms that can accurately classify samples according to physiological or disease states [42].

Ensemble and Traditional Classification Methods

Machine learning classifiers are particularly valuable for addressing the "large-p (features) and small-n (observations)" problem inherent in microbiome studies, where microbial features often vastly outnumber samples [42].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Classifiers on 29 Benchmark Human Microbiome Datasets [42]

| Method | Type | Key Characteristics | Performance Summary | Training Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Ensemble (Boosting) | Trees built sequentially; each reduces previous error; highly interpretable | Outperformed others in few datasets; comparable to RF and ENET in most | Longest |