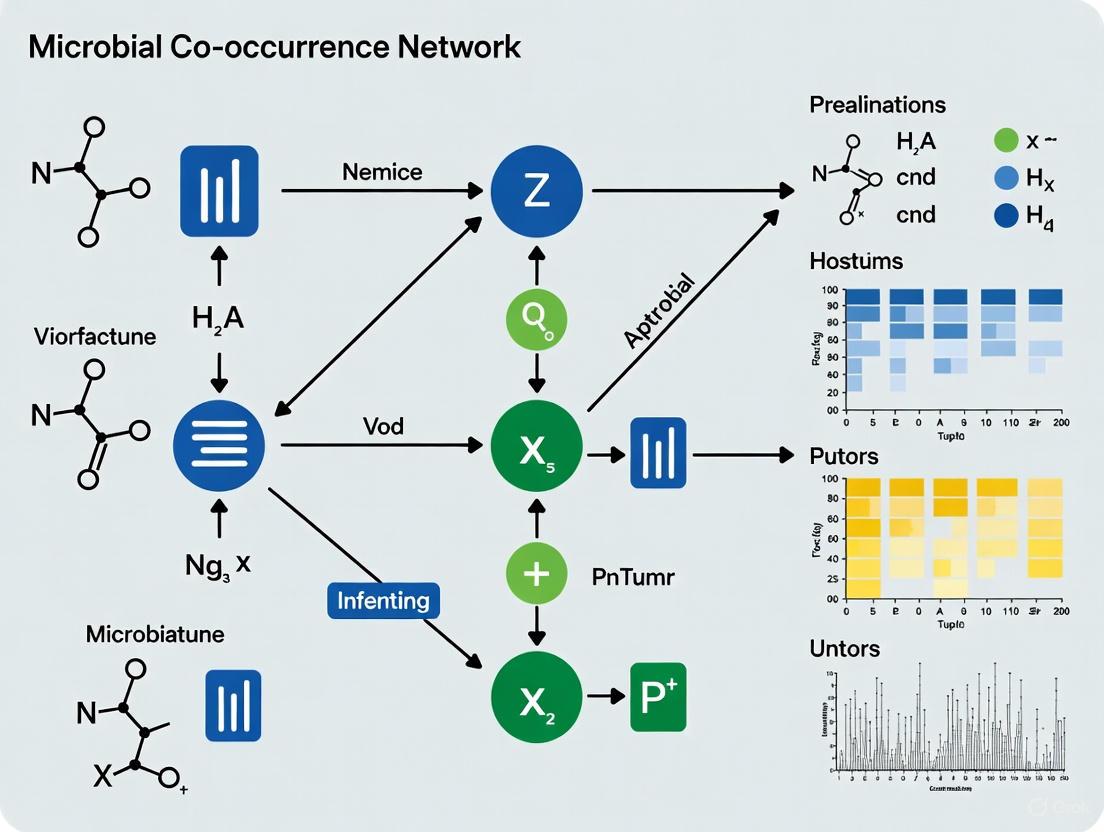

Microbial Co-occurrence Network Inference: A Comprehensive Guide to Algorithms, Validation, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of microbial co-occurrence network inference algorithms, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Microbial Co-occurrence Network Inference: A Comprehensive Guide to Algorithms, Validation, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of microbial co-occurrence network inference algorithms, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of microbial ecological networks and their importance in understanding health and disease. The review systematically categorizes and explains the core methodologies, from correlation-based to conditional dependence models, and addresses critical challenges including data compositionality, sparsity, and environmental confounders. A significant focus is placed on novel validation frameworks, such as cross-validation techniques, for hyper-parameter tuning and algorithm comparison. By synthesizing current tools and future directions, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to robustly infer, analyze, and interpret microbial interaction networks for biomedical discovery.

The Microbial Interactome: Unraveling Ecological Networks from Compositional Data

In the study of complex microbial ecosystems, co-occurrence networks have emerged as an essential tool for representing and analyzing the intricate web of interactions between microorganisms. These networks provide a systems-level perspective, shifting the focus from individual taxa to the relational patterns that define community structure and function. Within the specific context of microbial ecology, a co-occurrence network is a graph-based model where nodes represent microbial taxa and edges represent statistically significant associations between them, which may suggest potential ecological interactions [1] [2]. The inference of these networks from high-throughput sequencing data, such as 16S rRNA amplicon surveys, allows researchers to generate hypotheses about microbial community dynamics, identify keystone species, and understand how communities respond to environmental perturbations or associate with host health states [2]. The construction and interpretation of these networks, however, require careful methodological consideration, from data preprocessing and algorithm selection to statistical validation and ecological interpretation.

Definition and Structural Components

Fundamental Elements of a Co-occurrence Network

The architecture of a co-occurrence network is built upon a graph structure defined as ( G = (V, E) ), where ( V ) is the set of vertices (nodes) and ( E ) is the set of edges (links) [3].

- Nodes (Vertices): In microbial co-occurrence networks, nodes typically represent operational taxonomic units (OTUs), amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), or microbial taxa at various phylogenetic levels (e.g., genus, family) [2]. Each node corresponds to a distinct biological entity detected in the microbiome samples.

- Edges (Links): Edges connect pairs of nodes and represent a statistical association between the abundances of the two corresponding microbial taxa across a set of samples [1] [4]. These associations can be:

- Positive: Suggesting potential mutualism, commensalism, or shared habitat preference.

- Negative: Suggesting potential competition, amensalism, or divergent environmental responses [2].

- Edge Weight: The edges can be weighted, with the weight often indicating the strength or frequency of the co-occurrence relationship. A higher weight implies a stronger statistical association [1] [3].

Network Construction Criteria

The definition of a co-occurrence event is flexible and depends on the research question and unit of analysis, which fundamentally shapes the resulting network [4].

Table 1: Common Co-occurrence Criteria in Microbiome Studies

| Criterion Type | Definition | Implication for Edge Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Document-Based [1] | Two taxa co-occur if they are both present (above a detection threshold) in the same biological sample (e.g., the same soil core, host gut, or water sample). | Records co-occurrence at the sample level. Tends to produce denser networks. |

| Window-Based [1] | Two taxa co-occur if they are found within a predefined "window" of other taxa in a ranked abundance list or sequence. | Makes co-occurrence counts proportional to the proximity between taxa, potentially capturing more direct associations. |

The process of building a network from raw data involves multiple steps, including tagging the data (e.g., identifying OTUs), normalizing abundances, calculating association measures, and filtering non-significant links [1].

Analytical Framework and Ecological Interpretation

Key Network Topology Metrics

The topological properties of an inferred co-occurrence network provide quantitative insights into the structure and stability of the microbial community. Several graph-theoretic metrics are commonly used [1] [3].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Analyzing Co-occurrence Network Topology

| Metric | Definition | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Degree / Degree Centrality | The number of connections (edges) a node has. | Measures a taxon's connectedness. High-degree nodes ("hubs") may represent keystone species critical for community stability. |

| Betweenness Centrality | The number of shortest paths between other nodes that pass through a given node. | Identifies taxa that act as "bridges" between different modules, potentially facilitating communication or functional integration. |

| Closeness Centrality | The average distance (shortest path length) from a node to all other nodes in the network. | Identifies taxa that can quickly interact with or influence many others in the network. |

| Clustering Coefficient | The probability that two connected neighbors of a node are also connected to each other. | Measures the tendency of a node's partners to also be partners with each other, indicating local cliquishness or functional redundancy. |

| Modularity | The strength of division of a network into modules (communities or clusters). | High modularity suggests a community organized into distinct, tightly-knit groups of interacting taxa, which may represent functional guilds or niches. |

Community detection algorithms, such as modularity maximization, label propagation, or random-walk based methods like Infomap, are used to identify these modules or clusters of nodes that are more densely connected internally than with the rest of the network [1].

From Network Patterns to Ecological Meaning

The topological features of a co-occurrence network are not just mathematical abstractions; they can be interpreted in an ecological context [2]:

- Hub Taxa: Taxa with unusually high degree or centrality are often hypothesized to be keystone species. Their removal (in silico or in vivo) is predicted to disproportionately affect community stability and function.

- Module Composition: Clusters of tightly co-occurring taxa may represent groups of organisms that share a common functional role, occupy a similar micro-niche, or engage in tight symbiotic exchanges.

- Network-Level Comparisons: Differences in global properties like connectivity, modularity, or average path length between networks (e.g., healthy vs. diseased states) can reveal fundamental shifts in community organization and resilience.

Experimental Protocols for Network Inference

Protocol 1: Standardized Workflow for Inferring Microbial Co-occurrence Networks

Objective: To construct a robust microbial co-occurrence network from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing data. Input: An OTU/ASV table (samples x taxa) and associated metadata.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Rarefaction or Normalization: Normalize the raw count data to account for uneven sequencing depth. Common methods include total-sum scaling, rarefaction, or transformations like Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) for compositional data [2].

- Prevalence Filtering: Filter out low-abundance or low-prevalence taxa (e.g., those present in less than 10% of samples) to reduce noise and computational complexity.

- Association Measure Calculation:

- Select and compute a pairwise association measure for all pairs of microbial taxa across samples. Common choices include:

- Sparsification and Thresholding:

- Apply a statistical filter to the association matrix to retain only edges that are deemed significant, transforming the fully connected graph into a sparse network. This can be done using:

- Fixed Threshold: Retain edges with an absolute correlation above a set value (e.g., |r| > 0.6) [3].

- P-value Adjustment: Retain edges that survive a multiple-testing correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg FDR).

- Random Matrix Theory (RMT): Used by methods like MENAP to determine a data-driven threshold [2].

- Apply a statistical filter to the association matrix to retain only edges that are deemed significant, transforming the fully connected graph into a sparse network. This can be done using:

- Network Construction and Analysis:

- Graph Object Creation: Input the thresholded adjacency matrix into a network analysis toolbox (e.g.,

networkxin Python,igraphin R) to create a graph object [3]. - Topological Analysis: Calculate the metrics described in Section 3.1 (degree, betweenness, modularity, etc.).

- Visualization: Use visualization software (e.g., Gephi, Cytoscape) to generate a graphical representation of the network, often using a force-directed layout (e.g., Fruchterman-Reingold) where connected nodes are pulled together and disconnected nodes are pushed apart [1] [3].

- Graph Object Creation: Input the thresholded adjacency matrix into a network analysis toolbox (e.g.,

Protocol 2: Cross-Validation for Network Inference Algorithm Training

Objective: To select hyper-parameters (training) and compare the quality of inferred networks from different algorithms (testing) in the absence of a known ground truth, addressing a key challenge in the field [2].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Partitioning:

- Randomly split the sample set (rows of the OTU table) into ( k ) folds (e.g., ( k=5 )).

- Training and Prediction Loop:

- For each unique fold ( i ):

- Training Set: Use all folds except ( i ) to infer a network model. This involves running the chosen algorithm (e.g., LASSO, GGM) with a specific hyper-parameter value ( \lambda ).

- Test Set: Use the held-out fold ( i ).

- Prediction: Use the model learned from the training set to predict the associations in the test set. The specific implementation of this prediction step depends on the algorithm (e.g., for a correlation-based method, it might involve calculating the likelihood of the test data under the inferred correlation structure).

- For each unique fold ( i ):

- Error Calculation:

- Quantify the prediction error across all ( k ) folds. The nature of the error metric is algorithm-dependent.

- Hyper-parameter Selection and Model Evaluation:

- Training (for one algorithm): Repeat steps 2-3 for a range of hyper-parameter values (e.g., different L1 regularization strengths for LASSO). The value that minimizes the average cross-validation error is selected as optimal.

- Testing (between algorithms): Compare the cross-validation errors of different algorithms (e.g., Pearson, Spearman, LASSO, GGM) run with their optimally selected hyper-parameters. The algorithm with the lowest prediction error is considered to have the best generalization performance for that dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Microbial Co-occurrence Network Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Reference Databases (e.g., Green Genes, RDP [2]) | Provide curated phylogenetic reference sequences for classifying OTUs/ASVs. | Essential for the initial bioinformatic processing of raw sequencing reads into a taxon abundance table. |

| Association Inference Algorithms (e.g., SparCC [2], SPIEC-EASI [2], CCLasso [2]) | Core computational methods for calculating pairwise microbial associations from abundance data. | Choice of algorithm depends on data characteristics (e.g., compositionality, sparsity) and the type of association (e.g., correlation vs. conditional dependence). |

Network Analysis Software (e.g., networkx [3], igraph, Gephi [1] [3]) |

Libraries and platforms for constructing, analyzing, and visualizing graph networks. | networkx (Python) and igraph (R) are programming libraries for metric calculation. Gephi provides a GUI for interactive visualization and exploration. |

| Cross-Validation Framework [2] | A methodological approach for hyper-parameter tuning and model selection without ground truth data. | Critical for ensuring the robustness and generalizability of the inferred network, mitigating overfitting. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary computational power for intensive calculations. | Bootstrapping, cross-validation, and running complex algorithms on large datasets (hundreds to thousands of taxa) are computationally demanding. |

| Methyl 2-hydroxyhexadecanoate | Methyl 2-hydroxyhexadecanoate, CAS:16742-51-1, MF:C17H34O3, MW:286.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,3-Dioctanoyl glycerol | 1,3-Dioctanoylglycerol Research Compound | Explore 1,3-Dioctanoylglycerol for cell signaling research. This diacylglycerol is a key tool for studying PKC-independent pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The Critical Role of Microbial Networks in Human Health and Disease

The human body is a complex ecosystem inhabited by trillions of microorganisms—including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses—that collectively form the human microbiome [5] [6]. These microbial communities engage in intricate ecological interactions such as mutualism, competition, and commensalism, forming sophisticated co-occurrence networks that play a profound role in human health and disease [2] [7]. Co-occurrence network inference algorithms have emerged as essential computational tools for deciphering these complex microbial interactions, providing insights into community structure, stability, and function [2] [8]. The networks are graphical representations where nodes represent microbial taxa and edges represent statistically significant associations between them, which can be positive (indicating potential cooperation) or negative (suggesting competition or antagonism) [2]. Understanding these networks is crucial for developing targeted interventions in clinical settings, as they can reveal microbial signatures of various disease states and identify potential therapeutic targets [2] [9].

Table 1: Key Microbial Ecological Interactions in Human Health

| Interaction Type | Ecological Relationship | Potential Health Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Both interacting taxa benefit | Enhanced metabolic function, colonization resistance |

| Competition | Taxa compete for resources | Exclusion of pathogens, maintenance of diversity |

| Commensalism | One taxa benefits without affecting the other | Metabolic cross-feeding, community stability |

| Amensalism | One taxa inhibits another without being affected | Pathogen suppression, dysbiosis |

| Parasitism/Predation | One organism benefits at the expense of another | Disease progression, community disruption |

Microbial Network Inference Algorithms and Methodologies

Categories of Network Inference Algorithms

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to infer microbial co-occurrence networks from microbiome abundance data, each with distinct statistical foundations and assumptions [2] [7]. These algorithms can be broadly categorized into several classes based on their underlying methodologies.

Table 2: Major Categories of Co-occurrence Network Inference Algorithms

| Algorithm Category | Representative Methods | Underlying Principle | Key Hyper-parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Pearson, Spearman, MENAP, SparCC | Measures pairwise association strength between taxa | Correlation threshold, p-value cutoff |

| Regularized Linear Regression | CCLasso, REBACCA | Uses L1 regularization to infer sparse correlations | Regularization parameter (λ) |

| Gaussian Graphical Models (GGM) | SPIEC-EASI, MAGMA, mLDM | Estimates conditional dependencies via precision matrix | Sparsity parameter, model selection criterion |

| Mutual Information | ARACNE, CoNet | Measures linear and nonlinear dependencies using information theory | Mutual information threshold, DPI tolerance |

| Advanced Hybrid Methods | fuser (Fused Lasso) | Shares information across environments while preserving niche-specific signals | Fusion penalty, regularization parameters |

Experimental Protocol for Microbial Network Inference

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Microbial Co-occurrence Network Construction

Step 1: Sample Processing and Sequencing

- Collect samples from relevant anatomical sites (gut, oral, skin, etc.) using standardized sampling protocols [10]

- Extract microbial DNA using kits optimized for the specific sample type

- Perform 16S rRNA gene amplification targeting hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4 for bacteria) or shotgun metagenomic sequencing [10]

- Sequence amplified products using high-throughput platforms (Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore)

Step 2: Bioinformatic Processing

- Process raw sequencing data through quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming (Trimmomatic), and denoising (DADA2 for ASVs or UNOISE for OTUs) [9]

- Cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at 97% similarity or resolve Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [7]

- Perform taxonomic assignment using reference databases (Greengenes, SILVA, RDP) [2]

- Construct abundance tables with counts per taxon per sample

Step 3: Data Preprocessing for Network Analysis

- Apply prevalence filtering (typically 10-20% prevalence threshold) to remove rare taxa [7]

- Address compositionality using center-log ratio transformation or similar approaches [7] [9]

- Normalize for sequencing depth variation (rarefaction, CSS, or TSS) [10] [7]

- Apply log10(x+1) transformation to stabilize variance [11]

Step 4: Network Construction

- Select appropriate inference algorithm based on data characteristics and research question [2] [7]

- Optimize hyper-parameters using cross-validation or model selection criteria [2] [11]

- Compute pairwise associations between taxa

- Apply significance thresholds (with multiple testing correction) to determine edges

Step 5: Network Validation and Analysis

- Evaluate network quality using cross-validation approaches [2] [11]

- Calculate topological properties (modularity, connectivity, centrality measures) [7] [12]

- Compare networks between conditions (healthy vs. disease) using appropriate statistical tests

- Perform functional interpretation through integration with genomic or metabolic data

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Microbial Network Analysis

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., MoBio PowerSoil) | Microbial DNA isolation from complex samples | All sample types (stool, oral, skin) |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplification of target variable regions | Bacterial community profiling | |

| ITS Region Primers | Amplification of fungal target regions | Fungal community profiling | |

| Sequencing Kits (Illumina, Nanopore) | High-throughput DNA sequencing | Metagenomic and amplicon sequencing | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | QIIME2, mothur | Processing of raw sequencing data | 16S rRNA amplicon analysis |

| Kraken2+Bracken | Taxonomic profiling from metagenomic data | Shotgun metagenomic analysis | |

| Trimmomatic, FastQC | Quality control of sequencing reads | Preprocessing of raw data | |

| Network Inference Software | SPIEC-EASI | Compositionally robust network inference | Gaussian Graphical Models |

| SparCC | Correlation-based inference for compositional data | Correlation networks | |

| Flashweave | Conditional dependence networks | Large, sparse datasets | |

| fuser | Multi-environment network inference | Cross-study comparisons | |

| Analysis & Visualization | igraph, NetworkX | Network topology analysis | All network types |

| Cytoscape | Network visualization and exploration | Publication-quality figures | |

| NetCoMi | Comprehensive network comparison | Differential network analysis |

Advanced Methodological Frameworks

Cross-Validation for Network Inference Evaluation

Traditional methods for evaluating inferred networks, such as using external data or assessing network consistency across sub-samples, have significant limitations in real microbiome datasets [2]. A novel cross-validation approach has been developed specifically for training and testing co-occurrence network inference algorithms, providing robust solutions for hyper-parameter selection and algorithm comparison [2] [13].

Protocol 2: Same-All Cross-Validation (SAC) Framework

The SAC framework evaluates algorithm performance in two distinct scenarios [11]:

Scenario 1: Same Environment Validation

- Partition samples from a single environmental niche (e.g., gut microbiome from healthy individuals) into k-folds

- Train the network inference algorithm on k-1 folds

- Test the predictive performance on the held-out fold

- Repeat for all folds and average performance metrics

Scenario 2: Cross-Environment Validation

- Combine samples from multiple environmental niches (e.g., gut microbiomes from different disease states)

- Partition the combined dataset into k-folds, ensuring proportional representation of each niche

- Train on k-1 folds and test on the held-out fold

- Compare performance with Same Environment results to assess generalizability

This approach is particularly valuable for evaluating how well algorithms can predict microbial associations across diverse ecological niches or temporal dynamics, addressing a critical challenge in microbiome network inference [11].

Handling Compositional Data and Sparsity

Microbiome data presents unique analytical challenges due to its compositional nature (data representing proportions rather than absolute abundances) and high sparsity (many zero values) [7] [9]. Specific methodologies have been developed to address these challenges:

Protocol 3: Compositional Data Analysis Protocol

Step 1: Address Compositionality

- Apply center-log ratio (CLR) transformation to remove dependencies between proportions [7] [9]

- Alternatively, use Aitchison distance-based methods or employ compositionally-aware algorithms like SPIEC-EASI [7]

Step 2: Handle Zero Inflation

- Implement prevalence filtering (typically 10-20% threshold) to remove rarely observed taxa [7]

- Use pseudocount addition before log-transformation [11]

- Consider zero-inflated models or Bayesian approaches for sparse data

Step 3: Normalization

- Address uneven sequencing depth through rarefaction, cumulative sum scaling (CSS), or other normalization techniques [10] [7]

- Account for sampling bias by standardizing sampling intensity across treatments

Applications in Human Health and Disease

Microbial co-occurrence networks have revealed crucial insights into various disease states by identifying disruption patterns in microbial community structures. Meta-analyses of microbiome association networks have identified specific patterns of dysbiosis across multiple diseases, including enrichment of Proteobacteria interactions in diseased networks and disproportionate contributions of low-abundance taxa to network stability [9] [12].

Table 4: Network Topological Properties in Health and Disease States

| Disease State | Network Characteristics | Key Taxonomic Shifts | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Gut | High modularity, balanced positive/negative edges | Diverse core microbiota, stability-associated taxa | Metabolic harmony, colonization resistance |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Reduced connectivity, lower complexity | Depletion of anti-inflammatory taxa, pathobiont expansion | Immune dysregulation, barrier dysfunction |

| Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome | Altered modular structure, strengthened competition edges | Enriched fermentative taxa, reduced diversity | Energy harvest dysregulation, inflammation |

| Colorectal Cancer | Disrupted stability, hub rewiring | Enriched pro-carcinogenic taxa, depleted protective taxa | Genotoxin production, epithelial barrier disruption |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Cross-system network alterations | Oral-gut axis taxa association, reduced immunomodulatory taxa | Systemic inflammation, autoimmunity triggers |

Network analysis has demonstrated that lower-abundance genera (as low as 0.1% relative abundance) can perform central hub roles in microbial communities, maintaining stability and functionality despite their low abundance [12]. This challenges the traditional focus on abundant taxa and highlights the importance of considering ecological roles beyond relative abundance.

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis represents a paradigm shift in microbiome research, moving beyond differential abundance of individual taxa to understanding community-level interactions and their implications for human health [7] [9]. The methodological frameworks and protocols outlined here provide researchers with robust tools for inferring and validating these networks, while acknowledging current limitations and ongoing developments in the field. As network inference algorithms continue to evolve—with advances in multi-environment learning, compositionally robust methods, and integration of multi-omics data—these approaches will increasingly enable predictive modeling of microbiome dynamics and targeted therapeutic interventions [2] [11] [7]. The critical role of microbial networks in human health and disease underscores the importance of these computational approaches in advancing both basic science and clinical applications in microbiome research.

High-throughput sequencing technologies, such as 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, have revolutionized the study of microbial communities. The data generated from these studies possess several intrinsic characteristics that complicate their statistical analysis and biological interpretation. These characteristics must be rigorously addressed to draw meaningful conclusions about microbial ecology, host-microbiome interactions, and potential therapeutic applications. This application note details the three fundamental characteristics of microbiome data—compositionality, sparsity, and high-dimensionality—within the context of microbial co-occurrence network inference research. We provide experimental protocols for handling these data features and summarize key methodological considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Characteristics of Microbiome Data

Microbiome sequencing data present unique analytical challenges that distinguish them from other biological data types. The table below summarizes these core characteristics and their implications for co-occurrence network inference.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Microbiome Data and Their Analytical Implications

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on Analysis | Relevance to Network Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositionality | Data represent relative proportions rather than absolute abundances; an increase in one taxon necessitates a decrease in others [14]. | Spurious correlations; challenges in identifying true biological relationships. | Requires special correlation measures (e.g., SparCC) and log-ratio transformations to avoid false edges [2] [15]. |

| Sparsity | High percentage of zero counts due to true biological absence or undersampling of rare taxa [14] [16]. | Reduced statistical power; zero-inflation violates assumptions of many statistical models. | Complicates estimation of conditional dependencies; necessitates methods robust to zero-inflation like GLMs [14] [2]. |

| High-Dimensionality | Far more features (taxa, ASVs) than samples (p >> n scenario); can include hundreds to thousands of correlated features [14] [16]. | High risk of overfitting; increased computational complexity; challenges in visualization. | Requires regularization techniques (e.g., LASSO) and dimension reduction for computationally tractable and robust networks [2] [17]. |

| Overdispersion | Variance exceeds the mean in count data [14]. | Poor fit for standard Poisson models; inaccurate uncertainty estimates. | Affects reliability of edge weights and significance testing in inferred networks. |

| Non-Normality | Data follows non-normal distributions, often with heavy tails [14]. | Invalidates parametric tests assuming normality. | Necessitates use of non-parametric methods or generalized linear models [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Handling Data Characteristics

Protocol: Managing Compositional Data in Network Analysis

Principle: Address the compositional nature of data to avoid spurious correlations in co-occurrence networks.

Reagents and Materials:

- Software Environment: R or Python with appropriate packages

- Data Input: Normalized count table (e.g., from QIIME2, DADA2, DEBLUR)

- Reference Standards: Spike-in controls for absolute abundance (optional but recommended)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Perform careful quality control and filtering to remove low-abundance taxa while preserving community structure.

- Apply a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation or use analysis methods specifically designed for compositional data [15].

Algorithm Selection:

- Select network inference algorithms that account for compositionality, such as SparCC, which estimates correlations based on log-ratio transformed data [2].

- For more advanced modeling, consider methods like CCLasso or REBACCA that employ LASSO regularization on log-ratio transformed relative abundance data [2].

Validation:

Protocol: Addressing Data Sparsity in Microbial Community Analysis

Principle: Mitigate the effects of excess zeros in microbiome data to improve feature detection and relationship inference.

Reagents and Materials:

- Denoising Tools: DADA2 or DEBLUR for sequence variant inference

- Statistical Environment: R with packages for zero-inflated models (e.g., glm2, pscl)

- Validation Framework: MiCoNE pipeline or similar for systematic evaluation

Procedure:

- Data Processing:

- Process sequences using denoising algorithms that handle singletons appropriately. Note that DADA2 removes all singletons as part of its denoising algorithm, while DEBLUR retains them, which can affect downstream diversity metrics [18].

- Consider rarefaction to even sequencing depth, though be aware of potential information loss.

Modeling Approach:

- Implement generalized linear models (GLMs) with distributions appropriate for microbiome data (e.g., negative binomial, zero-inflated models) to handle overdispersion and zero inflation [14].

- For network inference, consider the novel GLM-ASCA approach that combines GLMs with ANOVA simultaneous component analysis to model the unique characteristics of microbiome sequence data [14].

Evaluation:

Protocol: Navigating High-Dimensional Data in Microbiome Studies

Principle: Employ dimensionality reduction and regularization techniques to extract meaningful signals from high-dimensional microbiome data.

Reagents and Materials:

- Computational Resources: Adequate memory and processing power for large datasets

- Software Packages: R with phyloseq, vegan, or Python with scikit-learn

- Visualization Tools: Advanced plotting libraries supporting high-dimensional data visualization

Procedure:

- Dimensionality Reduction:

- Apply principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) for beta-diversity visualization to understand overall community patterns [16].

- For structured experimental designs, utilize ASCA-based methods (ANOVA simultaneous component analysis) to separate the effects of different experimental factors in high-dimensional data [14].

Regularized Modeling:

- Implement regularization methods such as LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) to enforce sparsity in network inference [2] [17].

- For grouped samples across different environments, consider advanced methods like fused Lasso that retain environment-specific signals while sharing information across environments [17].

Network Inference and Validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Co-occurrence Network Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Tools/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Target amplification for microbial community profiling; selection affects diversity metrics captured [18]. | V1-V3, V3-V4, V4 hypervariable regions |

| Denoising Algorithms | Error correction in sequence data to resolve true biological variants from sequencing errors. | DADA2, DEBLUR [18] |

| Network Inference Algorithms | Infer microbial associations from abundance data using different statistical approaches. | SparCC, SPIEC-EASI, CCLasso, MAGMA [2] [15] |

| Cross-validation Frameworks | Hyperparameter tuning and algorithm evaluation without requiring external validation data. | Same-All Cross-validation (SAC) [17] |

| Consensus Network Tools | Generate robust co-occurrence networks by integrating results from multiple methods or subsamples. | MiCoNE pipeline [15] |

| Alpha Diversity Metrics | Quantify within-sample diversity using different mathematical approaches capturing complementary aspects. | Chao1 (richness), Shannon (information), Faith PD (phylogenetics) [18] |

| (+)-Cloprostenol methyl ester | (+)-Cloprostenol Methyl Ester | High-purity (+)-Cloprostenol methyl ester for veterinary reproductive research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Isorhamnetin 3-glucuronide | Isorhamnetin 3-glucuronide, CAS:36687-76-0, MF:C22H20O13, MW:492.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for processing microbiome data while accounting for its key characteristics, from raw data to network inference:

Microbiome Data Analysis Workflow: This workflow outlines the key steps in processing microbiome data for co-occurrence network inference, highlighting critical stages where compositionality, sparsity, and high-dimensionality must be addressed.

The characteristics of compositionality, sparsity, and high-dimensionality present significant but manageable challenges in microbiome research, particularly in co-occurrence network inference. By employing appropriate experimental protocols, statistical methods, and validation frameworks that specifically address these data features, researchers can extract more reliable biological insights. The continued development of specialized methods like GLM-ASCA for complex experimental designs and cross-validation frameworks for network evaluation represents important advances in the field. A thorough understanding of these data characteristics and their implications is essential for robust microbiome science with applications in microbial ecology, therapeutic development, and clinical translation.

The study of complex microbial communities has been revolutionized by high-throughput sequencing technologies, which enable comprehensive profiling of all genetic material in a sample [19]. For bacterial identification and microbiome analysis, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing has emerged as the predominant method with wide applications across food safety, environmental monitoring, and clinical microbiology [20]. This primer details the experimental and computational workflow for generating operational taxonomic units (OTUs) from raw sequencing data, framed within the critical context of microbial co-occurrence network inference research. The quality and resolution of OTU data directly impact the reliability of inferred ecological networks, which reveal complex microbial interactions through algorithms based on correlation, regularized linear regression, and conditional dependence [2] [21]. Understanding this foundational process—from sequencing to OTUs—is therefore essential for researchers investigating microbial interactions in health, disease, and environmental systems.

Experimental Design and Sequencing Technologies

Technology Selection: Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing

The choice between sequencing technologies represents a critical decision point that fundamentally affects downstream analytical resolution, including the fidelity of co-occurrence networks.

Table 1: Comparison of 16S rRNA Sequencing Approaches for Microbiome Studies

| Feature | Short-Read (Illumina) | Long-Read (Oxford Nanopore) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Partial fragments (e.g., V3–V4, ~400 bp) [22] | Full-length gene (V1–V9, ~1.5 kb) [20] [22] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Primarily genus-level [22] | Species-level identification [20] [22] |

| Read Length | Fixed, short reads | Unrestricted length reads [20] |

| Polymicrobial Sample Handling | Limited resolution in mixed samples | High resolution in polymicrobial samples [20] [23] |

| Typical Error Rate | Consistently high (Q30+) [22] | Recently improved (Q20 with R10.4.1) [22] |

| Primary Bioinformatics Approach | Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) via DADA2 [22] | Species-level identification with tools like Emu [22] |

The principal advantage of long-read technologies like Oxford Nanopore lies in their ability to span the entire ~1.5 kb 16S rRNA gene, encompassing all nine variable regions (V1–V9) in a single read [20]. This comprehensive coverage enables higher taxonomic resolution for accurate species identification, which is particularly valuable for detecting bacterial biomarkers in complex samples like those studied in colorectal cancer research [22]. For co-occurrence network inference, this enhanced resolution provides more precise nodes (taxa) for subsequent correlation analysis, potentially revealing interactions that would remain obscured with partial gene sequences.

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

The initial phase of the workflow focuses on obtaining high-quality input material suitable for the sample type and research question.

Sample-Type-Specific Extraction Protocols:

- Environmental Water Samples: ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit [20]

- Soil Samples: QIAGEN DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit [20]

- Stool Samples: QIAmp PowerFecal DNA Kit (microbiome DNA) or QIAGEN Genomic-tip 20/G (host and microbiome DNA) [20]

The extraction method must be selected to maximize DNA yield and quality while minimizing contamination, as these factors directly impact sequencing depth and the detection of rare taxa—a critical consideration for constructing comprehensive co-occurrence networks.

Library Preparation and Barcoding

For targeted 16S sequencing using Oxford Nanopore technology, the 16S Barcoding Kit enables multiplexing of up to 24 DNA samples in a single preparation [20]. This protocol involves:

- PCR Amplification: Amplifying the entire ~1.5 kb 16S rRNA gene from extracted gDNA using barcoded 16S primers

- Adapter Ligation: Adding sequencing adapters to the amplified products

- Pooling: Combining multiple barcoded libraries for efficient sequencing

This targeted approach ensures that only the region of interest is sequenced, providing economical bacterial identification while enabling sample multiplexing to reduce costs [20]. For network inference studies requiring multiple samples, this barcoding strategy facilitates the generation of sufficient data points for robust correlation analysis.

Sequencing Execution

The sequencing phase involves generating sufficient high-quality data to achieve the desired coverage and taxonomic resolution:

- Coverage Recommendation: 20x coverage per microbe for high taxonomic resolution [20]

- Typical Run Parameters: Sequencing on MinION Flow Cells using the high accuracy (HAC) basecaller in MinKNOW software for approximately 24–72 hours, depending on microbial sample complexity [20]

- Basecalling Options: Fast, HAC (High Accuracy), and SUP (Super-accurate) models, with empirical evidence showing similar taxonomic output across models but higher observed species with lower basecalling quality [22]

Bioinformatic Processing and OTU Generation

From Raw Sequences to Taxonomic Classification

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful taxonomic units involves a multi-step bioinformatic pipeline that must be carefully optimized for the specific sequencing technology employed.

Table 2: Bioinformatic Tools for 16S rRNA Sequence Analysis

| Tool | Technology | Method | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 [22] | Illumina | Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) | Error correction and OTU picking |

| Emu [22] | Oxford Nanopore | Species-level identification | Abundance profiling for noisy long reads |

| EPI2ME Fastq 16S [23] | Oxford Nanopore | Real-time analysis | Rapid taxonomic classification |

| NanoClust [22] | Oxford Nanopore | Clustering-based | OTU generation from long reads |

| QIIME2 [22] | Either | Pipeline integration | End-to-end microbiome analysis |

For short-read Illumina data, the DADA2 algorithm within QIIME2 pipelines provides precise Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) through error correction and chimera removal [22]. In contrast, the relatively higher error rate of Nanopore reads requires specialized tools like Emu, which performs abundance profiling designed for the specific noise profile of long-read data [22]. The choice of reference database (e.g., SILVA, Emu's Default database, Greengenes) significantly influences taxonomic classification, with different databases yielding variations in identified species and diversity metrics [2] [22].

Quality Control and Data Filtering

Robust quality control measures are essential for generating reliable OTU tables suitable for network inference:

- Quality Thresholds: Read filtering based on minimum quality scores (e.g., Q10 for Nanopore) and read length [23]

- Contaminant Removal: Identification and filtering of contaminant sequences based on control samples

- Read Trimming: Adapter and barcode removal, plus trimming of low-quality regions

Database selection profoundly affects results; while Emu's Default database may yield higher diversity and species counts, it can sometimes overconfidently classify unknown species as their closest matches due to its database structure [22]. This taxonomic accuracy directly influences co-occurrence network topology, as misclassification can introduce false nodes or obscure genuine ecological relationships.

Experimental Protocols for 16S rRNA Sequencing

Detailed Protocol: Oxford Nanopore Full-Length 16S Sequencing

Materials Required:

- Oxford Nanopore 16S Barcoding Kit 24 (SQK-16S024)

- MinION or GridION sequencer with flow cells

- Micro-Dx kit with SelectNA plus (Molzym GmbH & Co. KG) [23]

- Agilent 4200 TapeStation or similar QC instrument

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA using appropriate sample-specific method (see Section 2.2)

- Quality Assessment: Verify DNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry or fluorometry

- PCR Amplification: Amplify full-length 16S rRNA gene using barcoded primers (16S Barcoding Kit)

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing library according to SQK-SLK109 protocol with additional reagents from New England Biolabs [23]

- Sequencing: Load library onto MinION Flow Cell and sequence using high accuracy basecalling for 24-72 hours [20]

- Basecalling: Process raw data using Dorado basecaller with appropriate model (fast, hac, or sup) [22]

Critical Steps:

- Include negative controls throughout to detect contamination

- Use consistent PCR cycle numbers to minimize amplification bias

- For clinical samples, adhere to appropriate biosafety protocols

Analysis Protocol: Taxonomic Classification with Emu

Software Requirements:

- Emu (v3.0 or higher)

- R (v4.1 or higher) with phyloseq package

- SILVA database (v138) or Emu's Default database

Procedure:

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to samples based on barcodes

- Quality Filtering: Remove reads with average quality score

- Taxonomic Assignment: Run Emu with chosen database

- OTU Table Generation: Convert Emu output to phyloseq-compatible OTU table

- Downstream Analysis: Calculate diversity metrics, perform differential abundance testing

Validation:

- Compare results with alternative tools (e.g., NanoClust) when possible

- Validate against known cultures or spike-in controls

- Assess potential contaminants using dedicated packages (e.g., decontam)

Connecting OTU Generation to Co-occurrence Network Inference

The transition from OTU tables to ecological networks represents a crucial analytical bridge in microbial community analysis. The OTU tables generated through the workflows described above serve as the fundamental input for co-occurrence network inference algorithms, which employ various statistical approaches to detect significant associations between microbial taxa [2] [21]. These networks graphically represent potential ecological interactions, where nodes correspond to microbial taxa (derived from OTUs) and edges represent significant positive or negative associations [2].

The quality of the input OTU data profoundly impacts network reliability. Full-length 16S sequencing enhances network inference by providing species-level resolution for nodes, reducing the ambiguity that arises from genus-level groupings [22]. Additionally, the improved detection of polymicrobial presence enabled by long-read technologies [23] creates more complete network representations, potentially revealing keystone species that might be missed with partial gene sequencing approaches.

Recent methodological advances include novel cross-validation approaches for evaluating co-occurrence network inference algorithms, which help address challenges of high dimensionality and sparsity inherent in microbiome data [2] [21]. These validation frameworks enable robust hyperparameter selection for algorithms and facilitate meaningful comparisons between different network inference methods, ultimately strengthening the biological interpretations drawn from microbial association networks.

Visual Guide: From Sample to Ecological Insight

Visual Workflow: Comprehensive Pipeline from Sample Collection to Ecological Insight

This workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process from physical sample collection through computational analysis to biological interpretation. Key decision points—technology selection and database choice—fundamentally influence the resolution and accuracy of both OTU tables and subsequent co-occurrence networks. The color-coded phases distinguish wet lab (yellow), bioinformatic (green), and ecological inference (red) components, highlighting the multidisciplinary nature of modern microbiome research.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for 16S rRNA Sequencing and Analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit [20] | Optimized DNA extraction for environmental water samples |

| QIAGEN DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit [20] | Efficient DNA extraction from challenging soil samples | |

| QIAmp PowerFecal DNA Kit [20] | Microbiome DNA isolation from stool samples | |

| Library Preparation | Oxford Nanopore 16S Barcoding Kit 24 [20] | Targeted amplification and barcoding for multiplexing up to 24 samples |

| SQK-SLK109 Kit [23] | Ligation sequencing kit for whole genome and amplicon sequencing | |

| Sequencing | MinION Flow Cells [20] | Disposable sequencing cells for MinION/GridION devices |

| R10.4.1 Flow Cells [22] | Nanopore chemistry with improved accuracy for full-length 16S | |

| Analysis | EPI2ME wf-16s2 Pipeline [20] | Real-time and post-run analysis for species-level identification |

| Emu [22] | Taxonomic abundance profiling for noisy long reads | |

| SILVA Database [2] [22] | Curated database of aligned ribosomal RNA sequences | |

| NCBI RefSeq Database [23] | Comprehensive reference genome database for validation |

The journey from sequencing to OTUs represents a critical foundation for reliable microbial co-occurrence network inference. This primer has detailed the complete workflow, emphasizing how methodological choices at each stage—from technology selection through bioinformatic processing—fundamentally impact the taxonomic resolution and data quality essential for constructing meaningful ecological networks. The emergence of full-length 16S sequencing with long-read technologies provides enhanced species-level discrimination [20] [22], while continued development of specialized analytical tools addresses the unique challenges of different sequencing platforms. As network inference methodologies advance with improved validation frameworks [2] [21], the integration of high-quality OTU data will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the complex microbial interactions underlying human health, environmental processes, and disease pathogenesis.

A Toolkit for Researchers: From Correlation to Conditional Dependence Models

In microbial ecology, co-occurrence network inference has become an indispensable tool for unraveling the complex interactions within microbial communities. These networks, where nodes represent microbial taxa and edges represent significant associations, provide crucial insights into the structure and dynamics of microbiomes across diverse environments, from the human gut to soil and aquatic ecosystems [2]. The inference of these networks relies heavily on statistical association measures, with Pearson correlation, Spearman correlation, and SparCC emerging as fundamental workhorses in the field. Each algorithm brings distinct mathematical assumptions and capabilities to address the unique challenges posed by microbiome data, particularly its compositional nature and high sparsity [2] [24].

The growing recognition of the microbiome's role in human health and disease has intensified the need for robust network inference methods in pharmaceutical and therapeutic development [2]. Understanding microbial interactions through these networks can reveal novel biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and mechanisms of drug efficacy or toxicity. However, the choice of inference algorithm significantly impacts the resulting network structure and, consequently, the biological interpretations drawn from it [2]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these three cornerstone methods, detailing their theoretical foundations, practical implementation protocols, and applications in microbial research and drug development.

Algorithm Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Properties

Pearson Correlation measures the linear relationship between two continuous variables through the covariance of the variables divided by the product of their standard deviations [25]. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) ranges from -1 to +1, where +1 indicates a perfect positive linear relationship, -1 a perfect negative linear relationship, and 0 indicates no linear relationship [25] [26]. The formula for calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient for a sample is:

$$r{xy} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})(yi - \bar{y})}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})^2}\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(yi - \bar{y})^2}}$$

where $xi$ and $yi$ are the individual sample points, $\bar{x}$ and $\bar{y}$ are the sample means, and n is the sample size [25].

Spearman's Rank Correlation evaluates the monotonic relationship between two continuous or ordinal variables by applying Pearson correlation to rank-transformed data [27]. A monotonic relationship exists when one variable tends to change in a consistent direction (increasing or decreasing) with respect to the other, though not necessarily at a constant rate [28]. The Spearman coefficient (Ï or $r_s$) also ranges from -1 to +1, with similar interpretations as Pearson but for monotonic rather than strictly linear relationships [29] [27]. For data without ties, Spearman correlation can be calculated using:

$$\rho = 1 - \frac{6\sum d_i^2}{n(n^2 - 1)}$$

where $d_i$ is the difference between the ranks of corresponding variables, and n is the number of observations [27].

SparCC (Sparse Correlations for Compositional Data) specifically addresses the compositional nature of microbiome data, where sequencing results represent relative abundances rather than absolute counts [2] [30] [24]. This compositionality creates artifacts because an increase in one taxon's abundance necessarily causes apparent decreases in others [24]. SparCC estimates correlations by considering the log-ratio transformed abundance data and employs an iterative approach to reject spurious correlations based on the fact that the sum of all components must equal a constant (e.g., 1 for proportions or 100 for percentages) [2] [30].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Correlation Methods in Microbial Network Inference

| Feature | Pearson Correlation | Spearman Correlation | SparCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship Type Detected | Linear | Monotonic (linear or non-linear) | Linear (compositionally-aware) |

| Data Requirements | Continuous, normally distributed | Continuous or ordinal | Compositional count data |

| Handling of Compositional Data | Poor - susceptible to artifacts | Moderate - susceptible to artifacts | Excellent - specifically designed for it |

| Robustness to Outliers | Low | High | Moderate |

| Implementation in Tools | Widely available in statistical software | Widely available in statistical software | Specialized packages (SpiecEasi, SpeSpeNet) |

| Computational Complexity | Low | Low | High |

| 2-Bromo-5-iodopyridine | 2-Bromo-5-iodopyridine, CAS:73290-22-9, MF:C5H3BrIN, MW:283.89 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tetrabutylammonium Dibromoiodide | Tetrabutylammonium Dibromoiodide, CAS:15802-00-3, MF:C16H36Br2IN, MW:529.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Selection Guidelines for Microbial Data Analysis

Choosing the appropriate correlation method depends on the data characteristics and research questions:

Use Pearson correlation when variables are approximately normally distributed, the relationship is expected to be linear, and data are not compositional [26]. This method provides the highest statistical power for detecting true linear relationships when its assumptions are met.

Use Spearman correlation when data are ordinal, non-normally distributed, contain outliers, or when the relationship is expected to be monotonic but not necessarily linear [31]. It is more robust than Pearson for microbiome data but still suffers from compositionality artifacts.

Use SparCC specifically for microbiome relative abundance data, as it directly addresses compositionality concerns [2] [30]. It should be the preferred choice when analyzing 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing data or other compositional datasets where the total sum of abundances is constrained.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Across Data Types

| Data Scenario | Recommended Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized absolute abundances | Pearson or Spearman | Pearson if linearity and normality hold; Spearman otherwise |

| Relative abundance data (16S rRNA) | SparCC | Specifically handles compositionality; reduces false positives |

| Data with suspected outliers | Spearman | Rank-based approach minimizes outlier influence |

| Ordinal data or non-linear monotonic relationships | Spearman | Does not assume linearity |

| Large datasets with computational constraints | Spearman | Balance of robustness and computational efficiency |

| Ground truth available for validation | Compare multiple methods | Evaluate based on recovery of known relationships |

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Microbial Co-occurrence Network Inference

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for inferring microbial co-occurrence networks using Pearson, Spearman, and SparCC methods:

Protocol 1: Data Preprocessing for Correlation Analysis

Purpose: To prepare raw microbiome sequencing data for correlation-based network inference by addressing data quality issues and compositionality.

Materials:

- Raw OTU/ASV count table

- Taxonomic classification data

- Sample metadata

- Computing environment with R/Python and necessary packages

Procedure:

Data Import and Validation

- Load raw count data into analysis environment (R or Python)

- Verify data integrity by checking for missing values and formatting consistency

- Merge with taxonomic and metadata, ensuring sample identifiers match

Taxa Filtering [24]

- Apply prevalence filter: Retain taxa present in at least a minimum number of samples (typically 10-20% of samples)

- Apply abundance filter: Retain taxa with at least a minimum percentage of total reads (e.g., 0.001-0.01%) in one or more samples

- Document the number of taxa before and after filtering for reproducibility

-

- For Pearson/Spearman: Normalize using Total Sum Scaling (TSS) by dividing each count by the total reads per sample

- For SparCC: Use the built-in normalization procedure, which employs log-ratio transformation

- Address zero values using appropriate methods:

- For relative abundance data: Add small pseudo-counts (e.g., 0.5 or 1) to all values

- For CLR transformation: Use imputation methods designed for compositional data

Data Quality Assessment

- Generate summary statistics (mean, variance, sparsity) for the transformed data

- Create visualizations (histograms, PCA plots) to identify potential batch effects or outliers

- Document all parameters and transformations for reproducibility

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If data remains highly sparse after filtering, consider more aggressive filtering thresholds or specialized zero-handling methods

- If normalization fails to address compositionality, consider alternative approaches like ALDEx2 or ANCOM-BC before correlation analysis

Protocol 2: Implementing Correlation Analyses

Purpose: To compute pairwise associations between microbial taxa using Pearson, Spearman, and SparCC methods.

Materials:

- Preprocessed microbiome abundance data

- R statistical environment with packages:

SpiecEasi,psych,Hmisc

Procedure:

SparCC Implementation [30]

Multiple Testing Correction

Validation Steps:

- Check correlation matrix properties (symmetry, diagonal values = 1)

- Verify the range of correlation values falls between -1 and 1

- Confirm reasonable computation time for dataset size

Protocol 3: Network Construction and Validation

Purpose: To transform correlation matrices into microbial co-occurrence networks and validate their quality.

Materials:

- Correlation matrices and adjusted p-values from Protocol 2

- R environment with packages:

igraph,tidygraph,ggraph

Procedure:

Sparsity Threshold Application [2]

- Select significance threshold (typically FDR < 0.05 or 0.01)

- Apply correlation magnitude threshold (optional, e.g., |r| > 0.3)

- Create adjacency matrix:

Network Construction [24]

Network Validation using Cross-Validation [2]

- Implement SAC (Same-All Cross-validation) framework:

Topological Analysis

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Compare network properties across different correlation methods

- Assess stability of hub taxa across different inference approaches

- Evaluate biological consistency with known microbial relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Resources for Microbial Co-occurrence Network Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Package | Function in Analysis | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Packages for Correlation Analysis | psych |

Calculate correlations with p-values | Provides corr.test() for efficient correlation matrices with significance testing |

SpiecEasi |

Implement SparCC and other compositionally-aware methods | Includes sparcc() function and bootstrap procedures for p-values | |

Hmisc |

Advanced correlation analysis | Offers rcorr() function for efficient computation | |

| Network Construction & Visualization | igraph |

Network manipulation and analysis | Primary package for network operations and topology calculations |

tidygraph |

Integrated network manipulation | Compatible with tidyverse philosophy for easier data wrangling | |

ggraph |

Network visualization | Grammar-of-graphics approach to network plotting | |

| Specialized Microbiome Tools | SpeSpeNet |

User-friendly web application | No coding required; accessible interface for rapid network construction [24] |

NetCoMi |

Comprehensive microbiome network analysis | Includes multiple normalization and inference methods in unified framework | |

| Data Handling & Preprocessing | phyloseq |

Microbiome data management | Standard format for organizing OTU tables, taxonomy, and sample data |

tidyverse |

Data manipulation and visualization | Collection of packages including dplyr, ggplot2 for data wrangling | |

| Validation Frameworks | SAC Framework |

Cross-validation for network inference | Evaluates algorithm performance across different environments [17] |

| Butopamine hydrochloride | Butopamine hydrochloride, CAS:74432-68-1, MF:C18H24ClNO3, MW:337.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one | Tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one, CAS:143562-54-3, MF:C5H8O2, MW:100.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram details the specific steps for implementing each correlation method within the general workflow:

Applications in Microbial Research and Drug Development

The application of correlation-based network inference in microbial ecology and pharmaceutical development has yielded significant insights into community dynamics and host-microbe interactions. In clinical microbiology, these networks have revealed differences between healthy and diseased states, identifying potential microbial signatures of various conditions [2]. For instance, co-occurrence networks have been used to identify keystone taxa in the gut microbiome that may serve as novel therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic disorders, and even neurological conditions [2].

In drug development, correlation networks help elucidate how pharmaceutical interventions alter microbial communities and how these changes relate to treatment efficacy and side effects. The choice between Pearson, Spearman, and SparCC can significantly impact these interpretations. For example, SparCC's ability to handle compositionality makes it particularly valuable for analyzing microbiome changes in clinical trials, where relative abundance data is common [2] [24]. Recent advances in cross-validation frameworks, such as the SAC method, now enable more robust comparison of these algorithms and improve confidence in network-based discoveries [2] [17].

Emerging methodologies like the fused Lasso approach further enhance these applications by enabling environment-specific network inference, particularly valuable for understanding how microbial associations adapt to different physiological conditions or treatment regimens [17]. As microbiome-based therapeutics advance toward clinical application, the rigorous application and validation of these correlation-based network inference methods will play an increasingly critical role in translating microbial ecology into clinical insights.

In microbial ecology, inferring accurate co-occurrence networks from high-throughput sequencing data is a fundamental challenge. These networks, which represent ecological associations between microbial taxa, are crucial for understanding community structure and function in environments ranging from the human gut to soil ecosystems [32] [33]. However, microbiome data is inherently compositional, meaning that the measured relative abundances of microbes sum to a constant, which can lead to spurious correlations when using standard statistical methods [32] [2]. This limitation has driven the development of specialized computational approaches that can handle compositional constraints while inferring robust microbial associations.

Regularized regression techniques have emerged as powerful tools for addressing these challenges. The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) provides a framework for variable selection and regularization that is particularly valuable in high-dimensional settings where the number of potential features (microbial taxa) far exceeds the number of observations [34] [35]. By applying an L1-norm penalty, LASSO shrinks less important coefficients to zero, effectively performing automatic variable selection while preventing overfitting. This property makes it ideally suited for microbial network inference, where the goal is to identify the most meaningful associations among thousands of potential interactions.

Two advanced methods built upon this foundation are CCLasso and REBACCA, which adapt regularized regression specifically for compositional data. CCLasso employs a Lasso-penalized D-trace loss function to directly estimate sparse correlation matrices for microbial interactions [32], while REBACCA uses regularized estimation of the basis covariance based on compositional data [32] [2]. These methods represent significant advances over earlier correlation-based approaches by explicitly accounting for the compositional nature of microbiome data while leveraging the variable selection capabilities of LASSO regularization.

Algorithm Comparison and Theoretical Framework

Core Mathematical Principles

Regularized regression approaches for microbial co-occurrence network inference share a common foundation in addressing the statistical challenges posed by compositional data. The constant-sum constraint inherent in relative abundance data creates dependencies between variables that violate the assumptions of traditional correlation measures, potentially generating false positive associations [32] [33]. LASSO-based approaches address this through penalty functions that enforce sparsity, under the valid ecological assumption that most species pairs do not directly interact [32].

The standard LASSO optimization for Cox regression models, as applied in high-dimensional biological data, is formulated as:

Figure 1: LASSO Objective Function Components. The LASSO estimator combines a model fit measure (partial likelihood) with a penalty term that enforces sparsity in high-dimensional settings.

CCLasso specifically addresses compositional data by considering a novel loss function inspired by the Lasso-penalized D-trace loss, which avoids the limitations of earlier methods like SparCC that didn't properly account for errors in compositional data and could produce non-positive definite covariance matrices [32]. REBACCA, meanwhile, employs regularized estimation of the basis covariance using L1-norm shrinkage, making it considerably faster than iterative approximation methods like SparCC while maintaining accuracy [32].

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Regularized Regression Methods for Co-occurrence Network Inference

| Method | Core Approach | Key Innovation | Compositional Data Handling | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | L1-penalized regression | Variable selection via coefficient shrinkage | Requires pre-processing | High [35] |

| CCLasso | Lasso-penalized D-trace loss | Direct correlation estimation for compositions | Built-in via log-ratio transformation | Moderate [32] |

| REBACCA | Regularized basis covariance estimation | Sparse covariance matrix estimation | Built-in via statistical modeling | High [32] [2] |

| SparCC | Iterative approximation | Correlation estimation for compositions | Built-in via log-ratio transformation | Low [32] |

Performance Characteristics

Evaluation studies using realistic simulations with generalized Lotka-Volterra dynamics have revealed important performance characteristics of these methods. The performance of co-occurrence network methods depends significantly on interaction types, with competitive communities being more accurately predicted than predator-prey relationships [32] [33]. Additionally, these methods tend to describe interaction patterns less effectively in dense and heterogeneous networks compared to sparse networks [33].

Notably, comprehensive evaluations have shown that the performance of newer compositional data methods is often comparable to or only marginally better than classical methods like Pearson's correlation, contrary to initial expectations [32]. This highlights the fundamental challenges in inferring species interactions from compositional data alone, regardless of the statistical sophistication employed.

Application Notes

Practical Implementation Considerations

When implementing regularized regression approaches for microbial co-occurrence networks, several practical considerations emerge. Hyperparameter tuning is critical, as the choice of regularization parameter lambda directly controls network sparsity. Cross-validation methods have been developed specifically for this context, providing robust framework for parameter selection and algorithm evaluation [2].

The fuser algorithm represents an advanced implementation that extends these concepts by incorporating fused LASSO to handle grouped samples from different environmental niches. This approach retains subsample-specific signals while sharing relevant information across environments during training, generating distinct environment-specific predictive networks rather than a single generalized network [17]. This is particularly valuable in microbial ecology where communities adapt their associations to varying ecological conditions.

For high-dimensional survival contexts common in biomedical applications, adaptive LASSO variants have demonstrated superior performance. These assign different weights to each variable in the penalty term, addressing the inherent estimation bias in standard LASSO where constant penalization rates shrink all coefficients uniformly regardless of their true importance [34].

Integration with Analysis Pipelines

Regularized regression methods integrate effectively within broader microbial analysis frameworks. The mina R package exemplifies this integration, combining compositional analyses with network-based methods to enable nuanced comparison of microbial communities [36]. Such implementations demonstrate how LASSO-based approaches can be embedded within comprehensive analytical workflows that move beyond simple correlation networks to capture more ecologically meaningful relationships.

Another promising direction is the combination of multiple algorithms. For instance, Mutual Information (MI) techniques like ARACNE and CoNet can capture both linear and nonlinear associations, providing complementary insights to LASSO-based methods [2]. However, implementing cross-validation with MI remains mathematically complex due to the difficulty in defining conditional expectations in high-dimensional settings.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Co-occurrence Network Inference Methods

Objective

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of LASSO, CCLasso, and REBACCA in inferring microbial ecological networks from synthetic compositional data with known ground truth interactions.

Experimental Workflow

Figure 2: Method Benchmarking Workflow. This protocol uses simulated microbial abundance data with known interactions to quantitatively compare algorithm performance.

Step-by-Step Procedures

Synthetic Data Generation:

- Implement the n-species generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) equation to generate abundance data:

dN_i(t)/dt = N_i(t) * (r_i + ΣM_ij * N_j(t))whereN_i(t)is abundance of species i at time t,r_iis growth rate, andM_ijis the interaction matrix [32] [33]. - Generate interaction matrices

M_ijusing network models (random, small-world, scale-free) with varying average degrees to represent different connectivity scenarios [33]. - Simulate at least 100 different community structures for robust evaluation, covering mutualistic, competitive, and predator-prey interaction types [32].

- Implement the n-species generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) equation to generate abundance data:

Network Inference Application:

- Apply LASSO, CCLasso, and REBACCA to the simulated relative abundance data using multiple regularization parameters.

- Include comparator methods (Pearson, Spearman, SparCC) for baseline performance assessment [32].

- Implement appropriate data transformations for compositional nature (e.g., log-ratio transformations) where required by each algorithm.

Performance Evaluation:

- Calculate sensitivity and specificity against known interaction matrices using predefined thresholds [32].

- Compare network topologies using graph metrics including complexity, clustering coefficient, density, and centrality measures [36].

- Employ cross-validation techniques specifically designed for co-occurrence network algorithms to assess stability and generalizability [2].

Validation Metrics

- Primary Metrics: Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), Area Under Precision-Recall curve (AUPR)

- Secondary Metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-score, Matthew's Correlation Coefficient

- Network Topology Metrics: Degree distribution, clustering coefficient, betweenness centrality [36]

Protocol 2: Applying Regularized Regression to Microbiome Datasets

Objective

To implement LASSO, CCLasso, and REBACCA for inferring microbial co-occurrence networks from real microbiome sequencing data.

Experimental Workflow

Figure 3: Microbiome Data Analysis Workflow. This protocol applies regularized regression methods to real microbiome data to infer ecologically meaningful associations.

Step-by-Step Procedures

Data Preprocessing:

Feature Selection:

Network Inference:

- Apply LASSO, CCLasso, and REBACCA to the repASV abundance table.

- Use cross-validation to select optimal regularization parameters for each method [2].

- Generate adjacency matrices from significant associations (p < 0.01 after multiple testing correction).

Biological Validation:

- Compare inferred networks with known microbial interactions from literature and databases.

- Assess enrichment of co-occurring pairs in similar functional categories.

- Validate key inferences using independent datasets from similar environments.

Data Interpretation Guidelines

- Positive associations may indicate mutualistic relationships or similar environmental preferences

- Negative associations may suggest competitive interactions or different niche preferences

- Consider the ecological context when interpreting association signs and strengths

- Network topology measures can reveal community organization principles [36]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Regularized Regression Network Analysis

| Category | Item/Software | Specification/Version | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technology | 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | V4-V5 hypervariable regions | Microbial community profiling [2] [36] |

| Data Processing | DADA2 Pipeline | Version 1.14+ | ASV identification and error correction [36] |

| Reference Database | GreenGenes or RDP | Version 13_8 or later | Taxonomic classification of sequences [2] |

| Statistical Environment | R Programming | Version 3.5.1+ | Primary platform for analysis [32] [33] |

| Network Analysis | igraph Package | Version 1.2.2+ | Network generation and analysis [33] |

| Specialized Packages | mina R Package | Custom implementation | Diversity and network analysis integration [36] |

| Compositional Methods | SPIEC-EASI | Version 1.0+ | Comparative method for evaluation [32] [36] |

| Barnidipine Hydrochloride | Barnidipine Hydrochloride | Barnidipine Hydrochloride is a potent, long-acting L-type calcium channel blocker for hypertension research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or diagnostic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Bromo-2-chloropyridine | 4-Bromo-2-chloropyridine, CAS:73583-37-6, MF:C5H3BrClN, MW:192.44 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Considerations