Microbial Diversity and Abundance in Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems: Patterns, Processes, and Biomedical Implications

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on microbial diversity and abundance across terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, exploring foundational patterns, methodological approaches, and ecosystem-specific dynamics.

Microbial Diversity and Abundance in Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems: Patterns, Processes, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on microbial diversity and abundance across terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, exploring foundational patterns, methodological approaches, and ecosystem-specific dynamics. We examine how environmental filters and ecological processes shape microbial community assembly from glaciers to oceans and agricultural soils to forests. The article details advanced molecular techniques like FT-ICR MS and high-throughput sequencing that enable unprecedented resolution of microbial dark matter. For researchers and drug development professionals, we analyze how microbial community responses to environmental change offer insights for biotechnology and therapeutic discovery, while highlighting validation frameworks for comparing ecosystem-specific microbial functions.

Exploring the Unseen World: Distribution Patterns and Ecological Drivers of Microbial Diversity

Global Patterns of Microbial Diversity Across Earth's Ecosystems

Microbial diversity exhibits distinct global patterns across Earth's ecosystems, driven by a complex interplay of environmental factors, biogeographic principles, and ecosystem-specific conditions. This technical review synthesizes current research on microbial distribution in terrestrial, aquatic, and atmospheric environments, highlighting methodological advances in cultivation and computational analysis. We present quantitative comparisons of microbial communities across biomes, detailed experimental protocols for studying uncultivated microorganisms, and essential computational tools for modern microbial ecology. Understanding these patterns is crucial for predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change and harnessing microbial functions for biomedical and sustainability applications.

Microbial life demonstrates remarkable diversity and adaptation across Earth's ecosystems, functioning as fundamental drivers of global biogeochemical cycles [1]. The study of microbial biogeography has revealed that microorganisms are not universally distributed but rather exhibit predictable patterns across spatial and environmental gradients. These patterns are shaped by both deterministic factors (environmental selection, biotic interactions) and stochastic processes (dispersal limitation, ecological drift) [2]. Recent advances in molecular techniques, particularly high-throughput sequencing and metagenomics, have enabled researchers to move beyond cataloging diversity to understanding the functional implications and ecosystem services provided by microbial communities across biomes [3].

The investigation of microbial diversity patterns provides critical insights for multiple scientific disciplines. In microbial ecology, it helps elucidate the principles governing community assembly and function. For clinical and drug development professionals, understanding environmental microbial diversity serves as the foundation for discovering novel antimicrobial compounds and understanding pathogen evolution [4]. Furthermore, documenting baseline microbial distributions is essential for monitoring and predicting ecosystem responses to global change factors such as climate warming, pollution, and land use change [5].

Microbial Diversity Across Ecosystem Types

Terrestrial Ecosystems

Terrestrial ecosystems host highly diverse microbial communities that perform essential functions in nutrient cycling, soil formation, and plant health [1]. The composition and function of these communities vary significantly across climate zones and vegetation types. Polar and continental biomes exhibit higher belowground ecosystem multifunctionality (BEMF index of 0.55 and 0.48, respectively) compared to tropical and dry biomes (BEMF indices of 0.25 and 0.14, respectively) [5]. This pattern is largely driven by substantial soil nutrient reservoirs in polar regions despite lower productivity rates.

Forest ecosystems demonstrate successional patterns in microbial communities, with bacterial and fungal abundances increasing with forest succession in relation to both soil and litter characteristics [1]. Importantly, specific microbial functional genes related to carbohydrate degradation (e.g., cellulase, hemicellulase, and pectinase) increase with forest succession and correlate with soil abiotic factors such as organic carbon, total nitrogen, and moisture [1]. Agricultural systems show distinct microbial dynamics, where continuous cropping leads to autotoxicity through accumulation of harmful fungi and reduction of beneficial bacteria, significantly impacting crop productivity [1].

Table 1: Microbial Diversity Patterns Across Major Ecosystem Types

| Ecosystem | Key Microbial Groups | Dominant Phyla | Functional Specialization | Diversity Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial - Polar | Psychrophiles, Methanogens | Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria | Nutrient storage, Methanogenesis | High BEMF (0.55) [5] |

| Terrestrial - Tropical | Diverse heterotrophs | Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria | Rapid decomposition, Nutrient cycling | Low BEMF (0.25) [5] |

| Marine - Surface | Photoheterotrophs, Cyanobacteria | Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria | Carbon fixation, Primary production | High Shannon Diversity [2] |

| Freshwater | Oligotrophs, Methylotrophs | Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes | Organic matter mineralization | 40% genus-level diversity captured [6] |

| Atmosphere | Allochthonous communities | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes | Dispersal, Long-distance transport | Higher than aquatic systems [2] |

Aquatic Ecosystems

Aquatic ecosystems, including marine and freshwater environments, harbor microbial communities distinct from their terrestrial counterparts. Marine systems are dominated by Proteobacteria (58-66%) and Cyanobacteria (9-29%), with the relative abundance of Cyanobacteria to Proteobacteria being significantly higher in the Pacific Ocean (0.49 ± 0.06) compared to the Atlantic (0.14 ± 0.07) [2]. This regional variation highlights how water mass history, nutrient availability, and physicochemical conditions shape marine microbial biogeography.

Freshwater ecosystems are characterized by genome-streamlined oligotrophs adapted to low nutrient conditions [6]. Recent cultivation efforts using high-throughput dilution-to-extinction approaches have successfully isolated 627 axenic strains from 14 Central European lakes, representing up to 72% of genera detected in the original samples [6]. These cultures include 15 genera among the 30 most abundant freshwater bacteria, filling critical gaps in our understanding of freshwater microbial diversity. Importantly, these isolates represent slowly growing, genome-streamlined oligotrophs that are notoriously underrepresented in public culture repositories [6].

Atmospheric Ecosystems

The atmosphere serves as a dispersal highway for microorganisms, connecting terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems through bioaerosols. Airborne bacterial communities exhibit significantly higher diversity compared to surface water samples, with Proteobacteria dominating both environments (69 ± 12% in Pacific air, 64 ± 8% in Atlantic air) [2]. However, atmospheric communities show greater heterogeneity and stronger terrestrial influences, particularly Firmicutes (8-10%) and Actinobacteria (4-11%), which are predominantly associated with dust and soil sources [2].

Urban waterfront studies demonstrate that local sources significantly influence bioaerosols, with 50-61% of aerosol operational taxonomic units (OTUs) being unique to each site [7]. These urban aerial communities contain sewage-associated genera (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Blautia, and Faecalibacterium), demonstrating the widespread influence of anthropogenic pollution sources on microbial dispersal [7]. The ratio of autotrophic to heterotrophic bacteria in the atmosphere reveals regional differences in marine influence, with the Pacific atmospheric boundary layer showing significantly higher ratios (0.186 ± 0.029) compared to the Atlantic (0.005 ± 0.002) [2].

Methodological Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Traditional Cultivation and Modern Cultivation Techniques

Traditional microbial diversity studies relied on isolation and pure culture, followed by microscopic observation and physiological characterization [8]. These approaches suffer from fundamental limitations, as an estimated 99% of microbial species cannot be cultivated using standard laboratory techniques [3]. This "great plate count anomaly" arises because most environmental microbes are free-living oligotrophs adapted to low nutrient conditions that differ dramatically from nutrient-rich conventional media [6].

Advanced cultivation methods have emerged to address these limitations. High-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation uses defined media that mimic natural conditions, allowing researchers to isolate previously uncultivated taxa [6]. This approach involves serially diluting environmental samples to approximately one cell per well in 96-deep-well plates, followed by incubation for 6-8 weeks under in situ conditions [6]. The use of defined artificial media is preferable to autoclaved natural water for reproducible growth, as it avoids seasonally changing nutrient compositions and modification of essential components during sterilization [6].

Table 2: Key Methodologies in Microbial Diversity Studies

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivation-Based | Dilution-to-extinction, High-throughput cultivation | Isolation of novel taxa, Physiological studies | Most microorganisms remain uncultured, Media selectivity [6] |

| Molecular Fingerprinting | DGGE/TGGE, T-RFLP, SSCP | Community profiling, Rapid comparison | Low taxonomic resolution, Multiple bands from single taxa [8] |

| Sequencing-Based | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics | Comprehensive diversity assessment, Functional potential | DNA extraction biases, PCR artifacts [3] |

| Microarray-Based | PhyloChip, GeoChip | High-throughput profiling, Functional gene detection | Limited to known sequences, Cross-hybridization issues [8] |

| Microscopy-Based | FISH, CLASI-FISH | Spatial organization, Cell identification | Low throughput, Probe design challenges [8] |

Molecular and Computational Approaches

Molecular techniques have revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling culture-independent assessment of microbial diversity. Denaturant Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE) and Temperature Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (TGGE) separate PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes based on sequence-derived melting properties, allowing rapid profiling of microbial communities [8]. Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (T-RFLP) provides an alternative fingerprinting approach based on variations in restriction enzyme cutting sites [8].

Metagenomics, defined as the functional and sequence-based analysis of collective microbial genomes contained in an environmental sample, has become the cornerstone of modern microbial diversity studies [3]. This approach involves extracting total DNA from environmental samples, followed by sequencing and computational reconstruction of genomes and functional genes [3]. Recent large-scale initiatives have generated 54,083 high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes from marine environments alone, providing unprecedented insights into microbial functional potential [4].

Computational tools are essential for analyzing the enormous datasets generated by modern molecular methods. Genome annotation pipelines such as Prodigal, Prokka, and RAST facilitate gene prediction and functional annotation [3]. Phylogenetic analysis tools including RAxML, FastTree, and Gubbins enable reconstruction of evolutionary relationships, while visualization platforms like Microreact and Phandango allow researchers to explore and present complex genomic data [3].

Differential Abundance Analysis

Identifying differentially abundant microbes between sample groups represents a common but methodologically challenging goal in microbiome studies [9]. Multiple statistical approaches exist, each with different assumptions and performance characteristics. Compositional data analysis methods, including ALDEx2 and ANCOM, account for the relative nature of microbiome data by analyzing log-ratios between taxa [9]. Distribution-based methods such as DESeq2 and edgeR model read counts using negative binomial distributions, while limma voom applies linear models to precision-weighted log-counts [9].

Comparative evaluations across 38 datasets reveal that these tools identify drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa, with results heavily dependent on data pre-processing decisions such as rarefaction and prevalence filtering [9]. For example, limma voom (TMMwsp) identifies a mean of 40.5% significant amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) across datasets, while other methods identify as few as 0.8% [9]. This methodological variability underscores the importance of using multiple complementary approaches and transparent reporting of analytical decisions.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microbial Diversity Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Lysing enzymes, Detergents, Proteases | Cell lysis and nucleic acid liberation | Optimization required for different sample types |

| PCR Amplification | 16S rRNA primers (e.g., 27F/1492R), Polymerase | Target gene amplification | Primer selection critical for coverage and bias |

| Sequencing | Library preparation kits, Barcoded adapters | High-throughput sequencing | Platform-specific protocols (Illumina, PacBio, etc.) |

| Cultivation Media | Defined oligotrophic media, Carbon sources | Isolation of environmental microbes | Mimic natural conditions for uncultivated taxa [6] |

| Computational Tools | QIIME 2, mothur, USEARCH | Data processing and analysis | Extensive documentation and user communities |

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes, GTDB | Taxonomic classification | Regular updates crucial for accuracy [3] |

Climate Change Impacts on Microbial Diversity and Function

Climate change is projected to significantly alter global patterns of microbial diversity and ecosystem function. Research identifies an abrupt shift in belowground ecosystem multifunctionality at a mean annual temperature threshold of approximately 16.4°C [5]. In regions below this threshold (primarily polar and continental biomes), BEMF decreases rapidly with increasing temperature, while in warmer regions (MAT > 16.4°C), the temperature effect is negligible [5]. This nonlinear response highlights the vulnerability of cold-climate ecosystems to warming.

Future projections indicate that ongoing climate change will result in a 20.8% loss of global belowground ecosystem multifunctionality under the SSP585 scenario by 2100, with particularly severe impacts in temperate and continental biomes [5]. The mechanisms driving these changes differ across climate zones. In colder regions (MAT ≤ 16.4°C), temperature and soil pH generate strong negative effects on BEMF, whereas in warmer regions (MAT > 16.4°C), precipitation and plant species richness positively dominate BEMF dynamics [5].

Global patterns of microbial diversity reflect complex interactions between environmental filtering, dispersal limitations, and evolutionary history across Earth's ecosystems. Understanding these patterns requires integrating multiple methodological approaches, from advanced cultivation techniques for previously uncultivated taxa to sophisticated computational tools for analyzing high-throughput sequencing data. The documented responses of microbial communities to climate change highlight the urgency of incorporating microbial processes into global change models and conservation strategies.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the systematic exploration of microbial diversity across ecosystems represents a rich resource for discovering novel bioactive compounds and understanding fundamental biological processes. Future research directions should focus on integrating multi-omics data across temporal and spatial scales, developing more sophisticated models to predict microbial community responses to environmental change, and leveraging microbial functional diversity to address global sustainability challenges.

Environmental Gradients as Key Determinants of Community Structure

In both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, environmental gradients—spatial or temporal variations in abiotic factors—act as fundamental architects of microbial community structure, diversity, and function. These gradients, including temperature, pH, nutrient availability, salinity, and oxygen concentration, create a template upon which deterministic and stochastic processes shape microbial assembly. In structured environments, these factors can create a natural barrier to the establishment of invasive species or genes, such as antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), with higher microbial diversity significantly reducing ARG prevalence [10]. Understanding the mechanisms through which these gradients influence communities is paramount for predicting ecosystem responses to anthropogenic change, harnessing microbial functions for biotechnology, and informing drug development targeting microbial pathways. This whitepaper synthesizes recent research to provide a technical guide on how environmental gradients determine community structure across diverse ecosystems, with a focus on microbial communities.

Environmental Gradients and Microbial Community Dynamics

Key Gradients Structuring Microbial Communities

Environmental gradients establish selective pressures that filter microbial taxa, favor specific functional genes, and dictate the outcomes of species interactions. The table below summarizes the primary environmental gradients and their documented effects on microbial communities across various ecosystems.

Table 1: Key Environmental Gradients and Their Documented Effects on Microbial Communities

| Environmental Gradient | Ecosystem Studied | Impact on Microbial Community | Key Taxa or Functions Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity, Sulfate, Methane, Organic Carbon | Antarctic Lakes [11] | Strongest driver of community composition; shifts in structure and biogeochemical pathways. | Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, Pseudomonadota |

| Nitrogen-based Nutrients | Coastal Waters of the East China Sea [12] | Primary driver of bacterioplankton diversity, community assembly, and network stability. | Induces deterministic community assembly |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) and Nitrates (NO₃â») | Beibu Gulf Marine Environment [13] | DO influences community dissimilarity and stability; NO₃⻠drives network complexity. | Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Actinobacteria; Defined environmental thresholds identified |

| Electrical Conductivity & Bicarbonate | Low-Medium Enthalpy Springs, Mexico [14] | Significant impact on microbial community structure. | Pseudomonadota; Campylobacterota and Chlorobiota in specific springs |

| Soil Moisture (Drought) | Agricultural Soils, Poland [15] | Reduction reduces microbial activity, diversity, and enzyme production; alters community composition. | Decrease: Acidobacteriota, ActinobacteriotaIncrease: Drought-tolerant Gemmatimonadota |

| Microhabitat Type (Moss, Lichen, Soil) | Antarctic Ice-Free Terrestrial [16] | Stronger influence than geographic location; drives taxonomic composition and fine-scale functional specialization. | Mosses: NostocLichens: Endobacter, UsneaSoils: Highest unique OTUs |

Case Studies in Major Ecosystem Types

Aquatic Ecosystems: From Polar Lakes to Subtropical Seas

In the aquatic realm, gradients are often pronounced and directly linked to ecosystem function. A study of five lakes on King George Island, Antarctica, revealed that even within a relatively small geographic area, gradients of salinity, sulfate, methane, and organic carbon were the primary drivers of distinct microbial communities, overriding the effects of dispersal [11]. These communities, dominated by Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, and Pseudomonadota, also showed habitat-specific functional predictions for carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling [11].

Similarly, research in the Beibu Gulf demonstrated that dissolved oxygen (DO) and nitrate (NO₃â») gradients are critical for microbial community dynamics. DO was the key factor influencing bacterial dissimilarity and community stability, while NO₃⻠concentration drove network complexity. The study went a step further by identifying precise tipping points using segmented regression, with DO thresholds for beta diversity ranging from 5.93 to 6.31 mg/L [13].

In the East China Sea, a clear inshore-to-offshore environmental gradient, primarily driven by nitrogen-based nutrients from anthropogenic sources, structured bacterioplankton communities. This nutrient enrichment promoted deterministic community assembly, where environmental selection becomes more important than stochastic processes like random dispersal, and also enhanced the stability of the microbial co-occurrence networks [12].

Terrestrial Ecosystems: From Agricultural Soils to Antarctic Microhabitats

In terrestrial systems, soil moisture and microhabitat heterogeneity are powerful gradients. A two-month drought stress experiment on four agricultural soils in Poland revealed significant declines in microbial abundance and enzyme activities (e.g., dehydrogenases, phosphatases) [15]. The drought also caused a shift in community composition, with a decline in acidobacterial and actinobacterial populations but an increase in drought-resistant taxa like Gemmatimonadota [15].

In the ice-free regions of Antarctica, the type of microhabitat—moss, lichen, or bare soil—was found to be a stronger determinant of microbial community structure than geographic location [16]. While core ecological functions were maintained across microhabitats (suggesting functional redundancy), there was clear microhabitat-specific specialization. For instance, moss and lichen microhabitats were enriched with genes for carotenoid biosynthesis, an adaptive strategy to mitigate intense ultraviolet radiation [16].

Methodologies for Studying Gradient-Driven Community Dynamics

Core Experimental Protocols

To investigate the impact of environmental gradients on community structure, researchers employ a suite of standardized field and laboratory protocols. The following workflow visualizes a typical integrated approach, synthesizing methodologies from multiple studies [11] [12] [15].

Field Sampling and In Situ Measurement

- Water Column Sampling: For aquatic systems, water is collected using a peristaltic pump or Niskin bottles. A CTD profiler is used in situ to measure depth-resolved parameters like temperature, conductivity, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH [11] [13].

- Soil and Sediment Sampling: Terrestrial and benthic samples are collected using sterile corers or augers. Sediment cores are often subsampled at intervals (e.g., 1 cm or 3 cm) to resolve vertical gradients [11] [15].

- Biomass Collection for Molecular Analysis: For water, microbial biomass is concentrated by filtering a known volume (e.g., 1 L) sequentially through 3.0-μm and 0.22-μm polycarbonate membranes to capture particle-associated and free-living cells [13]. Soil/sediment samples are immediately frozen at -80°C after collection [11].

Laboratory Physicochemical Analysis

A range of analyses are performed on the collected samples to characterize the environmental gradient:

- Water Samples: Concentrations of inorganic nutrients (NOâ‚‚â» + NO₃â», NHâ‚„âº, PO₄³â») are determined using a continuous flow analyzer [11]. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is measured with a TOC analyzer. Sulfate (SO₄²â») is measured by ion chromatography, and dissolved gases (CHâ‚„, Nâ‚‚O) are analyzed via cavity ring-down spectrometry (CRDS) [11].

- Soil/Sediment Samples: Parameters like pH, organic carbon, total nitrogen, carbonate content, and available phosphorus are measured using standard protocols, such as an organic elemental analyzer for carbon and nitrogen [11] [15]. Water content is determined by measuring weight loss after freeze-drying [11].

Molecular Biology and Sequencing

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted from filters or soil/sediment samples using commercial kits, such as the DNeasy PowerWater Kit for water samples or the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit for soil/sediments [11] [13]. DNA quality and concentration are checked via electrophoresis or spectrophotometry.

- PCR Amplification and Sequencing: The hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) of the 16S rRNA gene are amplified using universal primers (e.g., 341F/805R). For fungal communities, the ITS region is targeted [16]. Amplified products are sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq or similar high-throughput platform [11] [13].

Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis

- Sequence Processing: Raw sequences are processed using pipelines like QIIME 2 or DADA2 to quality-filter, denoise, and cluster sequences into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), which provide high-resolution taxonomic units [11] [13].

- Community Analysis: Alpha-diversity (richness, Shannon index) and beta-diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, UniFrac) are calculated. Ordination methods like Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) and Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) are used to visualize community clustering. Statistical tests like PERMANOVA determine the significance of grouping factors [11] [10].

- Linking Communities to Gradients: Key environmental drivers are identified through correlation with ordination axes (BioEnv analysis) or modeled directly using distance-based linear models (DistLM) and redundancy analysis (RDA) [12] [15]. Segmented regression is used to identify critical environmental thresholds [13].

- Network Analysis: Co-occurrence networks are constructed based on strong correlations between ASVs to infer potential interactions and assess community complexity and stability [12] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Microbial Community Analysis

| Reagent / Kit / Technology | Primary Function | Specific Example / Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from complex environmental samples. | DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN) for water; PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio) for soil/sediment [11] [13]. |

| PCR Master Mix & Primers | Amplification of target marker genes for sequencing. | 2× Taq PCR Mastermix; Primers for 16S rRNA gene (e.g., 341F/805R) or ITS region [13]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Generating millions of DNA sequences for community profiling. | Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq platform [11] [13]. |

| Continuous Flow Analyzer | Precise, automated quantification of dissolved inorganic nutrients. | QuAAtro (SEAL Analytical) [11]. |

| Elemental Analyzer | Measurement of total carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur content in solid samples. | FLASH 2000 NC Organic Elemental Analyzer [11]. |

| Ion Chromatograph | Separation and quantification of ion concentrations (e.g., SO₄²â»). | Dionex Integrion HPIC (Thermo Fisher) [11]. |

| Cavity Ring-Down Spectrometer (CRDS) | Highly sensitive measurement of dissolved greenhouse gases (CHâ‚„, Nâ‚‚O). | Picarro CRDS analyzer [11]. |

| Ac-GpYLPQTV-NH2 | Ac-GpYLPQTV-NH2, MF:C38H60N9O14P, MW:897.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SPP-002 | SPP-002, MF:C24H41KO5S, MW:480.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Environmental gradients are indisputable key determinants of microbial community structure, acting through a complex interplay of deterministic selection, functional adaptation, and biotic interactions. The synthesis of research from Antarctic lakes, subtropical gulfs, agricultural soils, and geothermal springs consistently demonstrates that factors like nutrient availability, oxygen, salinity, and moisture create a predictable framework for community assembly. The identification of precise environmental thresholds and the recognition of functional redundancy alongside microhabitat specialization provide a more nuanced understanding of ecosystem stability and resilience. For researchers and drug development professionals, this body of knowledge is critical. It provides the predictive frameworks and methodological tools needed to understand microbial ecology in natural and engineered systems, to assess the environmental fate of bioactive compounds, and to explore the vast, untapped functional potential of microbial communities shaped by their environmental context.

Distinct Microbial Signatures in Aquatic vs. Terrestrial Ecosystems

Microbial communities are fundamental architects of Earth's biogeochemical cycles, and their compositional structures are distinctly shaped by the environments they inhabit. A growing body of global research confirms that fundamental phylogenetic divides separate the microbiomes of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, a pattern mirroring the distribution of plant and animal diversity [17]. These divisions are driven by contrasting environmental filters, energy sources, and anthropogenic pressures. Understanding these microbial signatures is critical for researchers and drug development professionals investigating microbial ecology, environmental genomics, and the discovery of novel bioactive compounds. This whitepaper synthesizes recent global findings to provide a technical guide on the defining characteristics of aquatic and terrestrial microbiomes, supported by comparative data, standardized methodologies, and analytical frameworks for ongoing research.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Diversity and Composition

Global comparative studies reveal that while local-scale microbial diversity can be similar, the community composition between land and sea represents one of the most significant phylogenetic splits in the microbial world.

Diversity Patterns and Community Structure

A massive analysis of 1,442 globally distributed 16S rRNA gene amplicon datasets demonstrated that microbial diversity is similar in marine and terrestrial microbiomes at local to global scales. However, community composition greatly differs between sea and land, forming a clear phylogenetic divide [17]. This suggests that the environmental and biological processes selecting for microbial lineages in these biomes are fundamentally distinct.

Table 1: Global Comparison of Surface Microbial Community Characteristics in Aquatic vs. Terrestrial Ecosystems

| Characteristic | Marine Ecosystems | Terrestrial Ecosystems |

|---|---|---|

| Major Bacterial Phyla | Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota, Cyanobacteriota [18] [19] | Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Acidobacteriota [20] |

| Archaeal Prevalence | Relatively high proportions in subsurface [17] | Varies, but often lower than in marine subsurface |

| Key Environmental Drivers | Salinity, pH, dissolved organic matter composition [17] [21] | Soil water availability, pH, vegetation, land use [20] |

| Anthropogenic Impact | Enrichment of pathogens & antibiotic resistance genes [19] | Reduced diversity, community structure shifts [22] |

| DOM Composition | Homogenized, recalcitrant, lignin-dominated [21] | More variable, influenced by plant and soil leachates [21] |

Distinct Taxonomic Compositions

The taxonomic profile of a specific environment provides a snapshot of its microbial signature. In a study of Shenzhen's coastal waters, distinct profiles emerged even within the same broader ecosystem. The western coasts, influenced by dense population and industry, were enriched with Synechococcales, Burkholderiales, and Microtrichales. In contrast, the eastern coasts, subject to tourism, were dominated by Vibrionales, Flavobacteriales, and Alteromonadales [19]. This highlights how anthropogenic stressors can select for specific microbial lineages, even within the same ecosystem type.

Similarly, in tropical aquatic ecosystems, the bacterial phylum Pseudomonadota can dominate, comprising between 38% to 83% of the total prokaryotic community, with genera like Limnohabitans and Marinobacterium being widespread [18]. In terrestrial systems, the same phylum (Pseudomonadota) is also common, but accompanied by a different suite of co-dominant phyla like Actinomycetota, which are crucial for decomposing complex organic matter in soils.

Methodologies for Characterizing Microbial Signatures

Accurate characterization of microbial communities requires standardized, high-resolution methodologies. The following section outlines key experimental protocols cited in recent literature.

Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing

The foundational step involves the careful collection of environmental samples and the extraction of genetic material.

- Sample Collection: For water samples, studies typically collect a defined volume of surface water (e.g., 300 ml [22]), which is then filtered through 0.22-μm pore-size membranes to capture microbial cells. For terrestrial samples, soil cores are collected from specified depths.

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: Total genomic DNA is extracted from the filters or soil using commercial kits (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit [22]). For community profiling, the 16S rRNA gene is targeted for bacteria and archaea, while the 18S rRNA gene is targeted for microbial eukaryotes. The hypervariable V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene is frequently amplified using primer pairs such as 338F (5'-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3') [22]. For eukaryotes, the V4 region of the 18S rRNA gene can be targeted with primers like 454F (5'-CCAGCASCYGCGGTAATTCC-3') and V4R (5'-ACTTTCGTTCTTGATYRA-3') [22].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Purified amplicons are sequenced on platforms such as the Illumina PE300 platform [22] or Illumina NovaSeq [19] to generate millions of paired-end reads.

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis

The resulting sequencing data is processed through a standardized bioinformatics pipeline to derive biological insights.

- Sequence Processing: Raw sequences are quality-controlled using tools like

fastpand merged withFLASH[22]. High-quality sequences are then denoised into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) using algorithms like DADA2 [22] within the QIIME2 pipeline [22]. ASVs provide a higher resolution than traditional Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). - Taxonomic Assignment: ASVs are classified taxonomically using reference databases such as the SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138) for bacteria and archaea [22], and specialized 18S databases for eukaryotes [22].

- Statistical and Ecological Analysis: Diversity indices (alpha and beta diversity) are calculated to compare communities within and between samples. Network analysis can be employed to understand co-occurrence patterns between microbes and functional genes, such as antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [19].

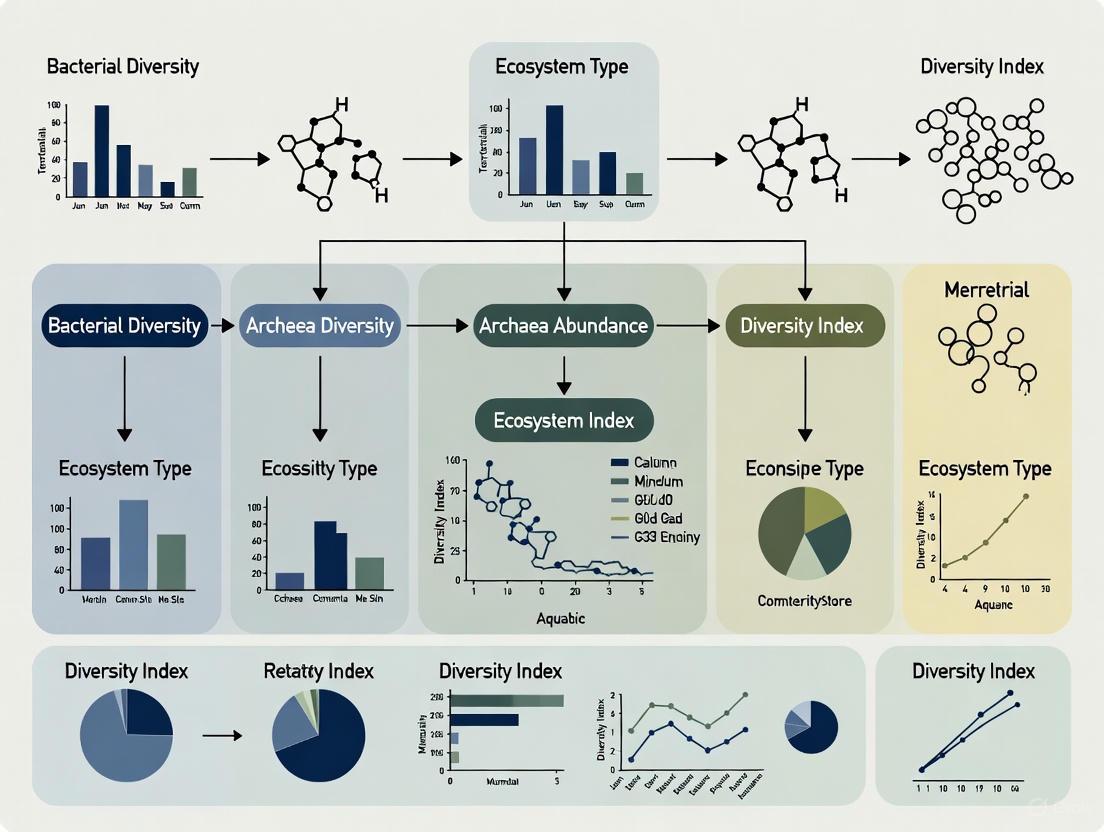

Figure 1: A standard workflow for microbial community analysis, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Cultivation of Challenging Microbes

While culture-independent methods are powerful, axenic cultures remain the gold standard for functional characterization. A key challenge is that most environmental microbes are free-living oligotrophs adapted to low nutrient concentrations, which are notoriously difficult to culture with standard nutrient-rich media [6].

- Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation: This technique involves serially diluting a environmental sample in a defined, nutrient-poor medium until, statistically, each well contains a single microbial cell. This prevents fast-growing copiotrophs from outcompeting slow-growing oligotrophs [6].

- Defined Media: Using artificial media that mimic natural conditions (e.g., low carbon content of 1.1-1.3 mg DOC per litre) is preferable for obtaining reproducible growth of aquatic oligotrophs, as it avoids the unpredictable composition of autoclaved natural water [6]. This approach has successfully isolated abundant yet previously uncultured freshwater lineages like Planktophila and Fontibacterium [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Ecology Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22-μm Filter Membranes | Concentration of microbial cells from aqueous samples. | Preparation of water samples for DNA extraction [22]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-purity genomic DNA from complex environmental samples. | E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit for consistent yield from soil/water filters [22]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Polymerases | Accurate amplification of target gene regions for sequencing. | Amplification of 16S V3-V4 region with Fast Pfu polymerase [22]. |

| Defined Oligotrophic Media | Cultivation of slow-growing, nutrient-sensitive environmental microbes. | Isolation of abundant aquatic oligotrophs via dilution-to-extinction [6]. |

| FT-ICR Mass Spectrometry | Ultrahigh-resolution analysis of dissolved organic matter (DOM) molecular composition. | Linking DOM chemistry to microbial community structure across ecosystems [21]. |

| SF2312 ammonium | SF2312 ammonium, MF:C4H14N3O6P, MW:231.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CORM-401 | CORM-401, MF:C8H6MnNO6S2-, MW:331.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Molecular Drivers of Microbial Signatures

Beyond taxonomy, the molecular composition of the environment plays a critical role in shaping and being shaped by microbial communities.

The Role of Dissolved Organic Matter (DOM)

DOM is one of the largest carbon pools on Earth and a key factor differentiating aquatic ecosystems. A study tracking DOM along a glacier-to-ocean continuum found a trend toward increasing homogenization and recalcitrance [21]. The proportion of "universal" DOM molecules present in all ecosystems studied increased from 65% in glaciers to 97% in the open ocean. This universal pool was dominated by lignin-like compounds, the relative intensity of which increased significantly along the gradient [21]. This suggests that physicochemical processes lead to homogenization, while biological transformations, driven by local microbial communities, increase the uniqueness of the DOM pool, particularly in glaciers and the open ocean [21].

Anthropogenic Impacts on Community Structure

Human activities are powerful drivers of microbial community composition. Research on the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau showed that anthropogenic disturbance reduces the diversity of bacteria, fungi, and protists in aquatic ecosystems, while increasing the relative abundance of dominant taxa [22]. Furthermore, human activities introduce specific selective pressures. In coastal megacities, this leads to the selective enrichment of human pathogens (HPBs) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [19]. Network analysis has revealed that these HPBs and ARGs can form complex associations, with some becoming hub species that may help shape the entire co-occurrence network in human-disturbed environments [19].

The distinct microbial signatures of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems are a product of deep phylogenetic divides, driven by fundamental differences in environmental physics, chemistry, and biotic interactions. Key differentiators include salinity, DOM composition and lability, and the nature of anthropogenic pressures. Advanced molecular techniques, coupled with innovative cultivation methods and sophisticated bioinformatics, are now allowing researchers to move beyond cataloging diversity to understanding the functional implications of these distinct communities. For scientists in both basic research and applied drug discovery, recognizing these ecosystem-specific signatures is the first step in harnessing microbial diversity for ecological forecasting, bioremediation, and the discovery of novel genetic and biochemical resources.

Universal vs. Ecosystem-Specific Microbial Molecular Formulae

The quest to determine whether microbial molecular processes are universal across ecosystems or specific to particular environments is fundamental to understanding microbial diversity and abundance in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. This question sits at the core of predictive microbial ecology, with significant implications for drug development, microbiome-based therapies, and ecosystem management. On one hand, compelling evidence suggests that microbial community dynamics and the molecular formulae of dissolved organic matter (DOM) can converge toward universal states, governed by common biochemical principles and degradation cascades [23] [24]. Conversely, other findings highlight the profound influence of ecosystem-specific conditions—such as nutrient concentrations, host physiology, and environmental gradients—on microbial molecular outputs [6] [25]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to dissect this dichotomy, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists navigating this complex field.

Universal Microbial Dynamics and Molecular Formulae

Evidence of Universal Dynamics in Host-Associated Microbiomes

Research into human-associated microbial communities has revealed that underlying ecological dynamics can be largely universal, even when species assemblages are highly personalized.

- Gut and Mouth Microbiomes: Analysis of cross-sectional data from the Human Microbiome Project and the Student Microbiome Project using the Dissimilarity-Overlap Curve (DOC) method showed a distinct negative slope in the high-overlap region for gut and mouth microbiomes. This pattern indicates that communities sharing more species also have more similar abundance profiles, a fingerprint of universal dynamics governed by common inter-species interactions [24].

- Stability After Intervention: The universality of gut microbial dynamics is disrupted in subjects with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection but is restored following a successful fecal microbiota transplantation, demonstrating the resilience of these core dynamics [24].

Convergence Toward a Universal Dissolved Organic Matter Pool

In aquatic and soil ecosystems, the processing of dissolved organic matter (DOM) consistently converges toward a core set of molecular formulae, irrespective of the starting material or specific environment.

Table 1: Changes in Universal DOM Compounds Along Environmental Gradients

| Ecosystem Gradient | Change in Proportion of Universal Compounds (Formula Count) | Change in Relative Abundance of Universal Compounds | Key Compound Classes Increasing in Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Depth (5 cm to 60 cm) | Increase from 20.9% to 23.9% [23] | Increase from 54.3% to 64.0% [23] | Lignin-like, carbohydrate-like, unsaturated hydrocarbon-like [23] |

| Hillslope to Stream (Shoulder to Stream) | No significant change [23] | Increase from 56.9% to 59.8% [23] | Lignin-like compounds [23] |

This convergence, termed a "degradation cascade", is driven by microbial activity that preferentially degrades non-universal, easily metabolizable compounds, leaving behind a persistent pool of difficult-to-degrade, universal molecules [23]. The expression of microbial genes essential for degrading plant-derived carbohydrates explains over 50% of the variation in the abundance of these persistent compounds [23].

Ecosystem-Specific Microbial Molecular Signatures

Cultivation Challenges and Ecosystem-Specific Growth Requirements

Despite evidence of universal patterns, a significant portion of environmental microbes remains uncultured due to highly specific and uncharacterized growth requirements, indicating ecosystem-specific adaptations.

- The "Great Plate Count Anomaly": Public culture collections are heavily biased toward fast-growing copiotrophs, which are often rare in nature. In contrast, many abundant aquatic prokaryotes are oligotrophs with genome-streamlined, reduced genomes and multiple auxotrophies, making them dependent on co-occurring microbes for essential nutrients [6].

- Isolation Success is Environment-Dependent: A large-scale cultivation effort of freshwater microbes found that isolation success was significantly lower in spring compared to summer and autumn, highlighting how seasonal environmental factors influence microbial cultivability [6].

Table 2: Cultivation Outcomes from a Freshwater Microbial Isolation Study

| Parameter | Result / Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Axenic Strains Isolated | 627 strains from 14 Central European lakes [6] | High-throughput methods can capture uncultivated majority |

| Genera Represented | 72 distinct genera, including 15 of the 30 most abundant freshwater genera [6] | Collection is representative of natural communities |

| Phyla Not Captured | Chloroflexota, Planctomycetota, and archaeal Thermoproteota [6] | Specific ecosystems (deep hypolimnion) host resistant-to-culture taxa |

| Growth Characteristics | Continuum from slow-growing oligotrophs to fast-growing copiotrophs [6] | Lifestyle and growth strategies are ecosystem-specific |

The Role of Environmental Heterogeneity in Shaping Evolution and Molecular Output

Microbial experimental evolution studies demonstrate that the environment is a critical determinant of evolutionary outcomes, which in turn shape molecular profiles.

- Environmental Parameters Drive Divergence: Controlled evolution experiments show that factors like population size and mutation rate fundamentally alter adaptive trajectories. Small populations are more susceptible to genetic drift, while mutation rate controls the supply of genetic variation [25].

- Eco-Evolutionary Feedback: As microbes evolve, they alter their own environment through waste products and resource consumption. This feedback creates new selective pressures, driving further evolution and diversification that is specific to the local conditions of the experiment [25]. This process is one mechanism behind the continuous evolution observed in long-term experiments and likely contributes to ecosystem-specific molecular signatures in nature.

Methodologies for Characterizing Microbial Molecular Signatures

High-Throughput Cultivation and Physiological Characterization

Protocol: Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation for Oligotrophic Microbes

- Principle: Diluting a microbial sample to approximately one cell per well in a low-nutrient medium prevents fast-growing copiotrophs from outcompeting slow-growing oligotrophs [6].

- Media Formulation: Use defined artificial media that mimic natural carbon and nutrient concentrations (e.g., 1.1-1.3 mg DOC per litre). Include a variety of carbohydrates, organic acids, vitamins, and catalase in µM concentrations [6].

- Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate 96-deep-well plates and incubate for 6-8 weeks at in situ temperatures (e.g., 16°C for freshwater lakes) [6].

- Screening and Validation: Screen wells for growth via visual turbidity or fluorescence. Test for axenic status by Sanger sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons from subsamples. Discard mixed or non-growing cultures [6].

- Growth Profiling: Characterize axenic strains in short-term growth assays across multiple media with varying carbon content to classify them as oligotrophs, mesotrophs, or copiotrophs based on growth rates and maximum cell yields [6].

Molecular Formula Analysis of Dissolved Organic Matter

Protocol: Tracking DOM Transformation via FT-ICR-MS

- Sample Collection and DOM Extraction: Collect soil pore water or aquatic samples along the gradient of interest (e.g., soil depth, hillslope positions). Use efficient extraction methods to maximize DOM recovery (target ~69% efficiency) [23].

- Ultrahigh-Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Analyze samples using Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR-MS). This technique provides the resolving power needed to detect and assign thousands of unique molecular formulae in a complex DOM sample [23].

- Data Analysis and Assignment:

- Assign molecular formulae to detected peaks.

- Classify formulae into biomolecular classes (e.g., lignin-like, carbohydrate-like, condensed hydrocarbon-like) based on their elemental compositions [23].

- Identify "universal" compounds as those molecular formulae present in every sample within the dataset.

- Calculate the relative abundance and proportion of universal compounds for each sample.

- Integration with Meta-Omics: Pair FT-ICR-MS data with shotgun metatranscriptomic sequencing of the same samples. This allows for the correlation of shifts in DOM composition with the expression of specific microbial metabolic genes [23].

Inferring Microbial Dynamics from Cross-Sectional Data

Protocol: Dissimilarity-Overlap Curve (DOC) Analysis

- Rationale: This computational method infers universal dynamics from cross-sectional data without the need for resource-intensive time-series experiments [24].

- Calculation of Pairwise Metrics: For all pairs of microbial community samples (e.g., from different subjects):

- Calculate Overlap, O(x̃,ỹ): The similarity of species assemblages, based on the relative abundances of species shared between two samples.

- Calculate Dissimilarity, D(x̂,ŷ): The dissimilarity between the renormalized abundance profiles of the shared species only [24].

- Plotting and Interpretation: Plot each sample pair as a point in the Dissimilarity-Overlap plane. Perform nonparametric regression to derive the average DOC.

- A negative slope in the high-overlap region is a fingerprint of universal dynamics with significant inter-species interactions.

- A flat DOC suggests individual-specific dynamics or a lack of significant interactions [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Molecular Ecology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Oligotrophic Media | Cultivation of slow-growing, environmental oligotrophs by mimicking natural nutrient conditions [6] | Carbon concentrations in the range of 1-2 mg DOC/L; includes vitamins, organic acids, and carbohydrates. |

| Methanol & Methylamine (C1 Compounds) | Selective cultivation of methylotrophic bacteria [6] | Used as sole carbon sources in defined media (e.g., MM-med). |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | Dissociation and subculturing of adherent mammalian cells in host-microbe interaction studies [26] | Typical concentration: 0.25% (w/v) trypsin, 0.03% (w/v) EDTA in saline without divalent cations. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Molecular cloning for genetic manipulation of microbial isolates or construction of recombinant plasmids [26] | Essential for functional characterization of genes. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Preparation of high-quality nucleic acids from complex environmental samples for meta-omics sequencing [27] | Protocols must be optimized for environmental matrices (soil, water, sediment). |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Amplicon-based phylogenetic profiling of bacterial and archaeal communities [27] | Choice of hypervariable region (e.g., V4) affects taxonomic resolution. |

| Frozen Glycerol Stocks | Long-term preservation of microbial isolates and evolved populations for future study [25] | Standard practice in experimental evolution to create a frozen "fossil record". |

| (RS)-Minesapride | (RS)-Minesapride, MF:C21H31ClN4O5, MW:454.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tyk2-IN-22-d3 | Tyk2-IN-22-d3, MF:C20H22N8O3, MW:425.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The dichotomy between universal and ecosystem-specific microbial molecular formulae is not absolute. Instead, microbial systems operate across a spectrum. Universal principles, such as the degradation cascade of DOM and shared ecological dynamics in stable environments like the human gut, provide a predictable framework [23] [24]. Simultaneously, ecosystem-specific factors, including nutrient availability, host physiology, and environmental heterogeneity, impose strong selective pressures that shape unique microbial assemblages and their molecular outputs [6] [25]. The path forward for researchers and drug development professionals lies in leveraging high-throughput cultivation, advanced molecular profiling, and sophisticated computational models like DOC analysis to dissect the relative contributions of these universal and specific forces. This integrated approach is paramount for translating our understanding of microbial ecology into actionable insights for medicine and ecosystem management.

The Role of Abundant and Rare Taxa in Maintaining Ecosystem Functions

In microbial ecology, ecosystems are characterized by a skewed abundance distribution where a limited number of highly active taxa coexist with a long tail of low-abundance species. This division between abundant and rare microbial taxa represents a fundamental aspect of ecosystem organization with significant implications for functional processes. The prevailing hypothesis of functional redundancy—where multiple species perform similar ecological roles—has historically suggested that ecosystem processes remain stable despite shifts in microbial composition. However, emerging research challenges this paradigm by demonstrating that both abundant and rare taxa contribute distinctively to ecosystem multifunctionality [28] [29]. This technical review synthesizes current understanding of how these microbial fractions support ecosystem stability and functionality across terrestrial and aquatic environments, providing methodologies and frameworks for researchers investigating microbial contributions to biogeochemical cycling.

Comparative Ecological Roles of Abundant and Rare Taxa

Defining Abundant and Rare Microbial Communities

Microbial taxa are typically classified based on their relative abundance and distribution patterns across ecosystems:

- Always Abundant Taxa (AAT): Maintain relative abundance ≥1% across all samples

- Conditionally Abundant Taxa (CAT): Reach ≥1% abundance in specific conditions

- Always Rare Taxa (ART): Consistently maintain relative abundance <0.01%

- Conditionally Rare Taxa (CRT): Fluctuate between rare and moderate abundance states

- Conditionally Rare and Abundant Taxa (CRAT): Exhibit dramatic abundance shifts across environments [28]

In practical research applications, abundant OTUs typically encompass AAT, CAT, and CRAT categories, while rare OTUs include ART and CRT groups [28].

Functional Contributions Across Ecosystems

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Abundant vs. Rare Taxa in Different Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Abundant Taxa Contributions | Rare Taxa Contributions | Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beetle-Killed Forest Soils | Maintain core metabolic functions | Preserve metabolic diversity during disturbance; transition between active/dormant states | Rare taxa contributed disproportionately to community dynamics after tree mortality [30] |

| Aquaculture Pond Systems | Dominate under stable conditions; support high-energy processes | Serve as diversity reservoirs; enhance system resilience | Rare OTUs numbered 6,003 (water) and 8,237 (sediment) vs. 199 and 122 abundant OTUs respectively [28] |

| Agricultural Soils | Drive decomposition of labile carbon compounds | Enable breakdown of recalcitrant carbon sources; maintain multifunctionality | Diversity loss reduced COâ‚‚ emissions by 40% and shifted decomposition toward labile C sources [29] |

| Managed Forest Systems | Maintain relatively stable abundance | Exhibit stronger biogeographic patterns; higher distance-decay relationships | Deterministic processes contributed more to rare community variation than abundant taxa [28] [31] |

Methodological Approaches for Studying Microbial Taxa

Experimental Workflows for Community Analysis

The following diagram illustrates integrated methodological approaches for analyzing abundant and rare microbial taxa across ecosystem types:

Classification Criteria for Microbial Taxa

Table 2: Operational Definitions for Categorizing Microbial Taxa

| Taxa Category | Relative Abundance Threshold | Distribution Characteristics | Detection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Always Abundant Taxa (AAT) | ≥1% in all samples | High prevalence across environments | Readily detectable via standard sequencing |

| Conditionally Abundant Taxa (CAT) | ≥0.01% in all samples and ≥1% in some | Context-dependent abundance shifts | Requires multi-habitat sampling |

| Always Rare Taxa (ART) | <0.01% in all samples | Persistent but low abundance | May require deep sequencing |

| Conditionally Rare Taxa (CRT) | <0.01% in some samples but never ≥1% | Fluctuating rare status | Sensitive to sequencing depth |

| Conditionally Rare and Abundant Taxa (CRAT) | Range from rare (<0.01%) to abundant (≥1%) | Highly dynamic across conditions | Key for understanding ecosystem transitions |

Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Ecology Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Research Application | Key Reagents/Techniques | Specific Function | Experimental Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | PowerSoil Total RNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories) | Concurrent DNA/RNA extraction from soil | Preserves relationship between presence and activity | ||

| cDNA Synthesis | High-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) | Converts RNA to cDNA for active community analysis | Requires RNA preservation in field (e.g., LifeGuard solution) | ||

| Sequence Amplification | Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase master mix | Amplifies V4 region of 16S rRNA gene | Dual-indexed primers reduce index hopping | ||

| Sequence Processing | QIIME toolkit (v1.9.1), USEARCH v6.1 | Demultiplexing, quality filtering, OTU picking | Singleton removal recommended for rare biosphere | ||

| Differential Abundance | metagenomeSeq package (fitZig test) | Identifies significantly different abundant OTUs | More powerful than rarefaction for rare taxa detection | ||

| Community Analysis | Weighted beta nearest taxon index (β-NTI) | Quantifies influence of ecological processes | β-NTI | >2 indicates deterministic processes |

Ecological Mechanisms and Community Assembly

Community Assembly Processes

Understanding the mechanisms governing microbial community assembly is crucial for predicting ecosystem responses to environmental change:

- Stochastic Processes: Dominate both abundant and rare community assemblies in aquatic ecosystems, including random birth-death events and probabilistic dispersal [28]

- Deterministic Processes: Contribute more significantly to rare taxa variation, with homogeneous selection (β-NTI < -2) and heterogeneous selection (β-NTI > 2) shaping communities under specific environmental conditions [28]

- Dispersal Limitation: Particularly influential for rare taxa, evidenced by stronger distance-decay relationships in rare versus abundant communities [28]

The Sloan neutral community model (SNCM) predicts the relationship between OTU detection frequency and abundance, revealing that rare taxa often occur outside neutral expectations, suggesting stronger environmental filtering or dispersal limitation [28].

Ecosystem Multifunctionality and Microbial Networks

The relationship between microbial diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) represents a critical research frontier:

- Diversity-Function Relationships: Microbial diversity significantly promotes EMF, with demonstrated impacts on carbon mineralization, nutrient cycling, and decomposition processes [29] [31]

- Network Complexity: Microbial co-occurrence networks with their relationships as links and microbial taxa as nodes form the backbone of effective material flow and energy transfer in ecosystems [31]

- Interactive Effects: Network complexity and diversity together drive the soil ecosystem multifunctionality of forests, with varying impacts across seasons and disturbance regimes [31]

Table 4: Impact of Microbial Diversity Manipulation on Soil Ecosystem Functions

| Diversity Level | OTU Richness (Bacteria) | Shannon Diversity | COâ‚‚ Emission Impact | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Community | 1,004 ± 98.8 | 5.48 ± 0.13 | Baseline (reference) | Balanced decomposition of labile/recalcitrant C |

| High Diversity (D1) | 659 ± 19.4 | 4.20 ± 0.09 | Reduced by ~15% | Shift toward preferential decomposition of degradable C |

| Medium Diversity (D2) | 435 ± 110.7 | 3.62 ± 0.54 | Reduced by ~25% | Impaired breakdown of recalcitrant compounds |

| Low Diversity (D3) | 313 ± 56.6 | 2.97 ± 0.40 | Reduced by up to 40% | Significant accumulation of recalcitrant organic matter |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The distinct functional roles of abundant and rare microbial taxa have profound implications for understanding ecosystem responses to environmental change. Rare taxa serve as metabolic reservoirs that maintain ecosystem functioning during disturbance events, as demonstrated in beetle-killed forests where rare microorganisms maintained metabolic diversity despite dramatic environmental shifts [30]. The preservation of microbial diversity appears particularly crucial for processes involving recalcitrant substrate degradation, where functional redundancy is naturally limited [29].

Future research should prioritize integrated approaches that simultaneously track taxonomic composition, metabolic potential, and ecosystem process rates across environmental gradients. Particular attention should focus on the dynamics of conditionally rare taxa that transition between abundance states, as these may represent keystone species for ecosystem stability. Furthermore, understanding how microbial network properties influence the relationship between diversity and function will enhance predictive models of ecosystem responses to global change scenarios [31].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights highlight the importance of preserving microbial diversity as a buffer against ecosystem functional loss. The methodologies and frameworks presented here provide robust approaches for investigating microbial contributions to ecosystem processes across terrestrial and aquatic environments.

Stochastic vs. Deterministic Processes in Microbial Community Assembly

Understanding the mechanisms that govern microbial community assembly—how species colonize, interact, and coexist to form local communities—is a central challenge in microbial ecology. This process is governed by the interplay between deterministic processes (niche-based selection driven by environmental conditions and species interactions) and stochastic processes (neutral-based events including ecological drift, probabilistic dispersal, and random extinction) [32]. The relative influence of these processes shapes microbial diversity, ecosystem function, and community responses to environmental change across terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [33]. This review synthesizes current knowledge on microbial community assembly mechanisms, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals studying microbial diversity and abundance.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Defining Assembly Processes

Microbial community assembly results from the combined action of four fundamental processes: selection, dispersal, drift, and diversification [33]. These processes can be categorized as either predominantly deterministic or stochastic.

Deterministic Processes are niche-based and predictable, governed by:

- Environmental filtering: Abiotic conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, salinity) that select for organisms with specific physiological traits [32] [34].

- Biological interactions: Competition, predation, mutualism, and other species interactions that affect fitness and survival [32].

- Homogeneous selection: Consistent environmental conditions lead to similar community compositions across habitats [32].

- Variable selection: Divergent environmental conditions lead to dissimilar community compositions [32].

Stochastic Processes are neutral and probabilistic, including:

- Ecological drift: Random changes in population sizes due to birth-death events [32] [33].

- Dispersal limitation: Incomplete mixing of communities due to geographical or biological barriers [32] [34].

- Homogenizing dispersal: High migration rates that make communities more similar [32].

- Historical contingency: The timing and order of species arrival (priority effects) influence subsequent community development [32].

Conceptual Framework for Community Assembly

The following diagram illustrates the interplay between stochastic and deterministic processes in microbial community assembly:

Methodological Approaches

Experimental Designs for Disentangling Assembly Processes

Researchers employ several experimental approaches to quantify the relative importance of stochastic and deterministic processes:

Temporal Sampling Designs track community changes over time to identify successional patterns. For example, a study on alpine lakes employed sampling at annual (monthly for 2 years) and short-term (daily and weekly) scales to reveal how process importance shifts across temporal scales [35].

Environmental Gradient Studies examine how communities respond to controlled or natural environmental variations. A 21-year experimental warming study on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau manipulated temperature in meadow and shrub ecosystems to assess how climate change alters assembly processes [36].

Neutral Community Modeling uses statistical approaches to test how well observed diversity patterns fit neutral predictions. Sloan's Neutral Model assesses whether community composition can be explained by random birth-death-disperal events without invoking niche differences [37] [38].

Null Model Analyses compare observed community patterns to randomly assembled communities to identify non-random elements indicating deterministic selection [34] [38].

Key Research Reagents and Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Tools for Studying Microbial Community Assembly

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | 16S/18S rRNA amplicon sequencing; Metagenomic sequencing | Taxonomic profiling; Functional potential assessment | Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) provide higher resolution than OTUs [35] |

| Cultivation Approaches | High-throughput dilution-to-extinction; Defined artificial media | Isolation of uncultivated taxa; Physiological studies | Media should mimic natural substrate concentrations [6] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME 2; DADA2; Phylogenetic placement algorithms | Data processing; Diversity calculations; Phylogenetic analysis | Enable differentiation diversity (β-diversity) metrics [33] |

| Statistical Frameworks | Neutral Community Model; Null model analyses; Variation partitioning | Quantifying stochastic/deterministic contributions | Sloan's model estimates migration rate and fit to neutral prediction [37] [38] |

| Environmental Monitoring | Multiparameter probes; Ion chromatography; Chemical assays | Measuring abiotic environmental factors | Critical for linking community changes to environmental drivers [35] |

Workflow for Community Assembly Analysis

A generalized experimental workflow for investigating microbial community assembly mechanisms is outlined below:

Empirical Evidence Across Ecosystems

Comparative Analysis of Aquatic and Terrestrial Systems

Table 2: Relative Influence of Stochastic and Deterministic Processes Across Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Study Details | Dominant Process | Key Influencing Factors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine Lake (Oligotrophic) | 2-year monthly sampling; ASV analysis | Homogeneous selection (66.7%) at annual scale; Homogenizing dispersal (55%) at daily/weekly scale | Temporal scale; Trophic state; Ice-cover duration [35] | |

| Subtropical River | Wet/dry season sampling; 18S rRNA sequencing | Stochastic processes (89.9% neutral model fit) | Hydrological regime; Conditionally rare taxa; Dispersal rate [37] | |

| Hypersaline Ponds (Salterns) | Light manipulation experiment; Metagenomics | Deterministic processes (light intensity) | Light availability; Pigment content; Disturbance frequency [39] | |

| Subsurface Sediments | Spatiotemporal sampling; Null models | Deterministic filtering at environmental extremes | Environmental variability; Spatial scale; Nutrient gradients [34] | |

| Activated Sludge Reactors | SRT manipulation; Neutral & null models | Start-up: Stochastic; SRT-driven: Deterministic | Operational parameters; Community succession stage [38] | |

| Alpine Meadow Soil | 21-year warming experiment; Seasonal sampling | Warming increased deterministic processes | Temperature; Vegetation type; Seasonality [36] |

Case Study: Temporal Scaling in Lake Ecosystems

A comprehensive study of alpine (Gossenköllesee) and subalpine (Piburgersee) lakes in the Austrian Alps revealed how the relative importance of assembly processes shifts across temporal scales [35]. Researchers collected composite water samples monthly over two consecutive years, with additional intensive daily and weekly sampling during August 2016.

The analysis of bacterial community turnover revealed that:

- At annual scales: Homogeneous selection (deterministic) dominated, explaining 66.7% of community turnover despite trophic differences between lakes

- At daily/weekly scales: Homogenizing dispersal (stochastic) became most important, explaining 55% of community variation in the alpine lake

This demonstrates that temporal scale fundamentally influences which assembly processes appear most important, with deterministic processes dominating over longer timeframes and stochastic processes more influential in short-term dynamics.

Case Study: 21-Year Warming Experiment

A long-term warming experiment on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau provides insights into how climate change alters assembly processes [36]. Researchers simulated warming in meadow (GL) and shrub (SL) ecosystems over 21 years and collected seasonal samples.

Key findings included:

- Warming significantly decreased bacterial alpha diversity in GL but not SL

- Deterministic processes increased under warming, with variable selection strength increasing from 11.2% to 20.1%

- Community time decay relationships (TDR) slowed under warming, indicating greater stability

- Warming simplified bacterial co-occurrence networks and increased the proportion of specialist species

This demonstrates that environmental perturbations can shift the balance between stochastic and deterministic processes, with implications for ecosystem stability under climate change.

Implications for Microbial Ecology and Applied Sciences

Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences

The balance between stochastic and deterministic processes has profound implications for microbial diversity patterns and ecosystem functioning. When deterministic processes dominate, communities become more predictable and specialized, potentially enhancing specific ecosystem functions but reducing functional redundancy [36]. Conversely, when stochastic processes dominate, communities maintain higher functional redundancy but may be less optimized for specific environmental conditions [37].

The influence of these assembly processes extends to biogeochemical cycling, as the specific taxonomic composition and functional attributes of microbial communities directly impact processes like carbon sequestration, nitrogen cycling, and organic matter decomposition [36]. Understanding these relationships is crucial for predicting ecosystem responses to global change.

Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine

In engineered systems, manipulating assembly processes can optimize community functions. For example, in wastewater treatment systems, operational parameters like sludge retention time can be adjusted to select for desired functional groups [38]. Understanding assembly rules also aids in designing synthetic microbial communities with predictable behaviors.

In drug development, comprehending microbial assembly in human-associated microbiota can inform probiotic design and microbiome-based therapeutics. The concepts of priority effects and historical contingency explain how initial colonizers might shape long-term community composition, with implications for preventing pathogen establishment [32].

Future Directions and Research Needs

Several key challenges remain in understanding microbial community assembly:

- Integration of scales: Linking process importance across spatial and temporal scales

- Taxonomic resolution: Determining whether different microbial taxa follow consistent assembly rules

- Functional traits: Connecting phylogenetic patterns to functional attributes and ecosystem processes

- Experimental manipulation: Developing approaches to directly test assembly mechanisms rather than inferring them from patterns

Recent methodological advances, including high-throughput cultivation [6] and more sophisticated null models [38], are addressing these challenges. The ongoing integration of molecular techniques, theory, and experiments promises continued insights into the complex interplay of stochastic and deterministic processes in microbial community assembly.

Microbial Responses to Climate Change and Anthropogenic Pressure

Microbial communities in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems are undergoing profound transformations in response to climate change and anthropogenic pressures. This technical review synthesizes current research demonstrating how rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and multiple human-induced stressors reshape microbial diversity, function, and ecosystem services. Evidence reveals consistent patterns of functional gene loss, community restructuring, and altered biogeochemical cycling across ecosystems, with critical implications for global carbon storage, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience. Experimental data highlight the particular vulnerability of microbial functions when confronted with multiple simultaneous stressors, suggesting that biodiversity conservation alone may be insufficient to maintain ecosystem processes without simultaneous reduction of anthropogenic pressures. This synthesis provides a framework for researchers investigating microbial ecological dynamics and developing mitigation strategies in an era of rapid global change.

Microorganisms constitute the invisible majority of Earth's biodiversity and serve as fundamental regulators of ecosystem stability, nutrient cycling, and climate feedback processes [20]. In terrestrial environments, soil microbes mediate decomposition, soil formation, and carbon sequestration, while in aquatic systems, they drive biogeochemical cycles and form the base of food webs [40] [41]. The accelerating pace of climate change—characterized by rising temperatures, altered precipitation regimes, and increasing frequency of extreme events—is generating unprecedented selective pressures on these microbial communities [20] [42].

Concurrently, anthropogenic activities introduce multiple additional stressors including chemical pollution, nutrient eutrophication, and habitat disturbance [43] [44]. Understanding microbial responses to these combined pressures is critical for predicting ecosystem trajectories and developing effective conservation and mitigation strategies. This review synthesizes current evidence of microbial responses to climate change and anthropogenic pressures across ecosystem types, with particular emphasis on functional consequences, methodological approaches, and research priorities.

Microbial Response Patterns Across Ecosystems

Terrestrial Ecosystem Responses

Soil microbial communities demonstrate measurable and often predictable responses to climate change factors, though these responses are complicated by interactions with local environmental conditions and biotic factors.

Table 1: Documented Microbial Responses to Climate Change in Terrestrial Ecosystems

| Environmental Driver | Taxonomic Response | Functional Response | Ecosystem Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Increase | Reduced taxonomic diversity; shifted composition [43] | Increased C-cycling capacity; altered enzymatic activities [45] | Changes in soil carbon storage; altered nutrient cycling rates [20] |

| Drought/Precipitation Change | Community restructuring along moisture gradients [20] | Reduced microbial activity; increased metabolic limitations [20] | Decreased decomposition rates; impaired nutrient cycling [20] |

| Multiple GCF Co-occurrence | Reduced fungal abundance; simplified community structure [44] | Elimination of biodiversity-ecosystem function relationships [44] | Loss of ecosystem multifunctionality; reduced resilience [44] |

Research along elevational gradients provides natural laboratories for understanding temperature impacts. Studies in Tibetan forests reveal that soil water availability significantly structures fungal communities across elevations, with functional groups showing distinct distribution patterns [20]. Similarly, experimental warming treatments demonstrate consistent reductions in soil bacterial diversity, though network complexity may initially increase under moderate warming [43].