Microbial Engines: How Bacteria and Archaea Drive Global Carbon, Nitrogen, and Sulfur Cycles

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the indispensable roles microorganisms play in Earth's biogeochemical cycles.

Microbial Engines: How Bacteria and Archaea Drive Global Carbon, Nitrogen, and Sulfur Cycles

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the indispensable roles microorganisms play in Earth's biogeochemical cycles. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational mechanisms of microbial carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur transformations, from well-established pathways to newly discovered processes like iron oxide respiration. It delves into advanced methodological approaches, including metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, for studying these communities. The content further addresses challenges in modeling and environmental perturbation, compares microbial functions across diverse ecosystems, and validates their global impact. Finally, it synthesizes key insights and discusses future implications for environmental management and biomedical research, emphasizing the critical interplay between microbial ecology and planetary health.

The Unseen Workforce: Microbial Catalysts of Earth's Elemental Cycles

Biogeochemical cycles are fundamental pathways that describe the movement and transformation of chemical elements and compounds between living organisms (the biosphere) and the abiotic compartments of Earth: the atmosphere, lithosphere, and hydrosphere [1]. These cycles are essential for life, as they recycle and conserve matter, ensuring that vital elements like carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur remain available to organisms [2]. While energy flows unidirectionally through ecosystems, matter is conserved and recycled [2]. Microorganisms are the primary regulators of these biogeochemical systems, driving the metabolic processes that control global cycles [3]. Incredibly, microbial production is so immense that global biogeochemistry would likely remain unchanged even in the absence of eukaryotic life [3]. This guide provides a technical overview of the microbial drivers in the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles, framing them within contemporary research methodologies and findings.

Microbial Drivers in Key Biogeochemical Cycles

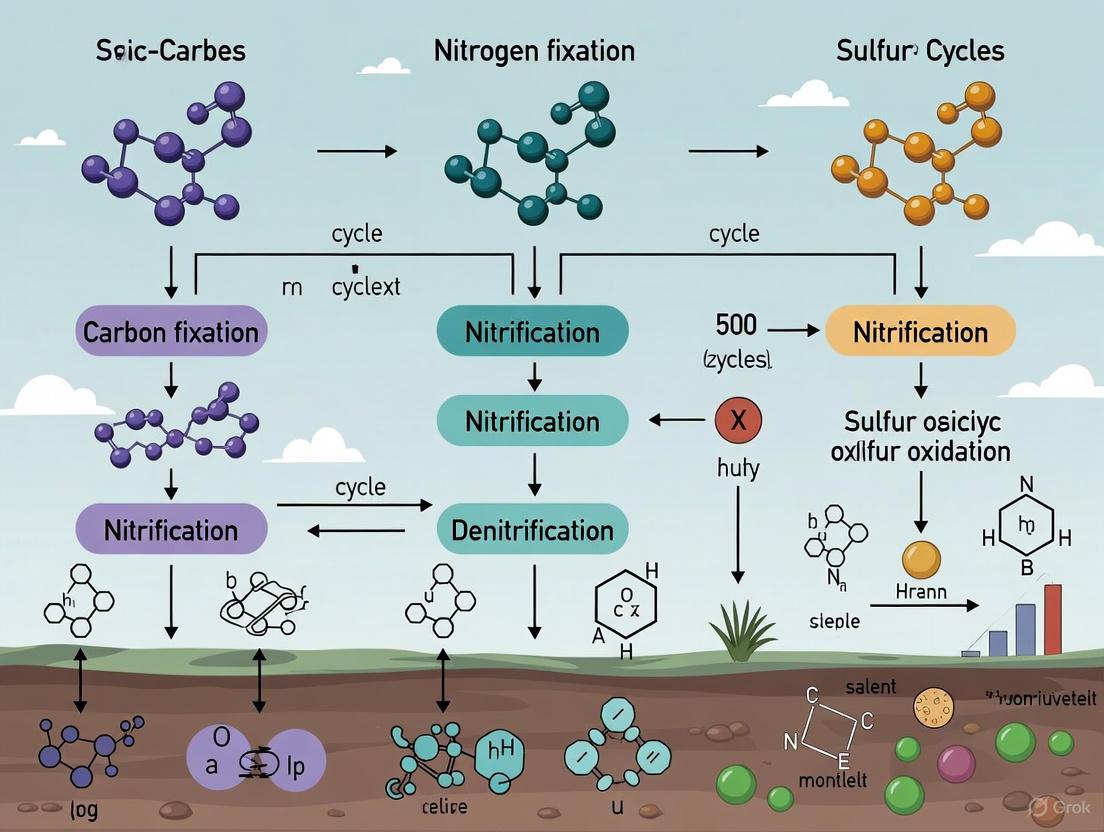

Microorganisms mediate key steps in biogeochemical cycles through diverse metabolic processes. Their collective activities, including nitrogen fixation, carbon fixation, and sulfur metabolism, effectively control global biogeochemical cycling [3]. The following sections detail their roles in the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles, supported by quantitative data from recent studies.

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon is the fundamental building block of all organic compounds. The carbon cycle involves the storage and fluxes of carbon throughout the Earth system [4]. The transformative process by which carbon dioxide is taken up from the atmosphere and incorporated into organic substances is called carbon fixation, with photosynthesis being a key example [3].

Microorganisms drive multiple pathways in the carbon cycle. For instance, in deep marine sediments of the Kathiawar Peninsula, metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) revealed diverse carbon fixation pathways, including the Calvin cycle, Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, and 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate cycle [5]. In reclaimed water rivers, phytoplankton photosynthesis was identified as a major process, fixing approximately 342.24 tons of carbon, while simultaneous decomposition of sediment organic matter released about 246.21 tons of carbon back into the water [6]. In mangrove ecosystems, functional gene analysis (GeoChip) showed that carbon degradation is the most active process, with carbon degradation genes accounting for 69% of the detected carbon cycle genes [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Microbial Processes in the Carbon Cycle

| Ecosystem | Process | Key Microbial Groups/Genes | Quantitative Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Marine Sediments [5] | Carbon Fixation | MAGs from phyla Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Planctomycetota, Desulfobacterota | Identified 6 major autotrophic pathways |

| Reclaimed Water River [6] | Phytoplankton Photosynthesis | Phytoplankton | 342.24 t C fixed |

| Reclaimed Water River [6] | Organic Matter Decomposition | Sediment Microbiome | 246.21 t C emitted from SOM degradation |

| Mangrove Soils [7] | Carbon Degradation | Functional gene amyA (for starch degradation) | Highly abundant |

The Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen is essential for nucleic acids and proteins. Although the Earth's atmosphere is primarily composed of nitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚), it is relatively unusable for most organisms [3]. Nitrogen fixation, the process of converting atmospheric Nâ‚‚ into ammonia, is almost entirely carried out by bacteria possessing the enzyme nitrogenase [3].

Microbial processes dominate the nitrogen cycle. Research in mangrove ecosystems has shown that denitrification is a crucial process, with the functional gene narG (nitrate reductase) being highly abundant [7]. In the deep marine sediments of the Kathiawar Peninsula, MAGs were found to possess complete pathways for key nitrogen transformations, including denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) [5]. Furthermore, specific bacterial genera like Neisseria and Pseudomonas were found to synergistically participate in the nitrogen cycle within mangroves [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Microbial Processes in the Nitrogen Cycle

| Ecosystem | Process | Key Microbial Groups/Genes | Quantitative Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Marine Sediments [5] | Denitrification & DNRA | MAGs from Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Planctomycetota | Complete pathways identified in 275 MAGs |

| Mangrove Soils [7] | Denitrification | Functional gene narG | Highly abundant |

| Mangrove Soils [7] | Synergistic Activity | Genera Neisseria, Pseudomonas | Participated in multiple N-cycle steps |

The Sulfur Cycle

Sulfur is critical for the three-dimensional structure of proteins [1]. The sulfur cycle involves various oxidation and reduction states, and in the deep sea, sulfur compounds can serve as primary energy sources in the absence of sunlight [1].

Microorganisms are central to sulfur transformations. In deep marine sediments, a significant number of MAGs were involved in sulfur redox reactions, including sulfur oxidation, sulfate reduction, and sulfite reduction [5]. The functional gene dsrA (dissimilatory sulfite reductase) was found to be highly abundant in mangrove soils, indicating that sulfite reduction is a crucial process in that environment [7]. Studies also show that bacteria such as Desulfotomaculum can synergistically participate in both the sulfur and carbon cycles [7].

Table 3: Quantitative Microbial Processes in the Sulfur Cycle

| Ecosystem | Process | Key Microbial Groups/Genes | Quantitative Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Marine Sediments [5] | Sulfur Redox Reactions | MAGs from Desulfobacterota, Gammaproteobacteria | Key pathways identified |

| Mangrove Soils [7] | Sulfite Reduction | Functional gene dsrA | Highly abundant |

| Mangrove Soils [7] | Synergistic Activity | Genus Desulfotomaculum | Linked S and C cycles |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Microbial Biogeochemistry

Understanding microbial drivers requires advanced molecular techniques that move beyond cultivation, as the vast majority of environmental microorganisms cannot be grown in a lab [5]. The following workflow outlines a standard metagenomic approach.

Sample Collection and Processing

- Sample Collection: Environmental samples (e.g., soil, sediment, water) are collected from the field using sterile equipment. For sediments, a meter-long gravity corer is often used [5]. In studies of shrub expansion, surface soil (0-20 cm depth) is collected from multiple random points within a plot and homogenized to create a composite sample [8].

- Storage: Samples are immediately transported to the laboratory on ice. Subsamples for DNA analysis are stored at -80°C to preserve nucleic acid integrity, while other subsamples are air-dried for physicochemical analysis [8].

Metagenomic DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Data Processing

This protocol synthesizes methodologies from multiple studies on sediments and soils [5] [8].

- DNA Extraction: Total genomic DNA is extracted from samples using commercial kits (e.g., ALFA-SEQ Advanced Soil DNA Kit). The extracted DNA is checked for integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis and for concentration/purity using instruments like a Qubit Fluorometer and Nanodrop Spectrophotometer [8].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Sequencing libraries are prepared using kit-based protocols (e.g., ALFA-SEQ DNA Library Prep Kit). High-throughput paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2 x 150 bp) is performed on platforms such as the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 [8].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Raw sequencing reads are trimmed to remove adapters and low-quality bases using tools like Trimmomatic [8].

- Assembly: Filtered reads are assembled de novo into longer sequences (scaffolds/scaftigs) using assemblers like MEGAHIT [8].

- Gene Prediction and Cataloging: Open Reading Frames (ORFs) are predicted from assembled scaftigs using tools like MetaGeneMark. A non-redundant gene catalog is created using CD-HIT to cluster similar sequences [8].

- Gene Abundance and Annotation: Clean reads from each sample are mapped back to the gene catalog to calculate abundance profiles. The gene sequences are then annotated by comparing them against reference databases (e.g., NCBI NR) using BLASTP [8]. For functional analysis, genes can be matched against specialized databases like Pfam for protein families or CAZy for carbohydrate-active enzymes [5].

- Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): High-quality assemblies can be binned into MAGs using tools like MetaBAT, and their taxonomy classified with GTDB-Tk. Metabolic pathways are then reconstructed from the MAGs [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Metagenomic Studies

| Item | Specific Example | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | ALFA-SEQ Advanced Soil DNA Kit [8] | Efficiently extracts genomic DNA from complex environmental samples like soil and sediment. |

| DNA Quality Instruments | Qubit Fluorometer, Nanodrop Spectrophotometer [8] | Precisely measure DNA concentration and assess purity (e.g., A260/A280 ratio). |

| Library Prep Kit | ALFA-SEQ DNA Library Prep Kit [8] | Prepares sequencing-ready libraries from extracted DNA by fragmenting, end-repairing, and adding adapters. |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 [8] | Performs high-throughput, paired-end sequencing of DNA libraries. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Trimmomatic, MEGAHIT, MetaGeneMark, CD-HIT, BBMAP [8] | A suite of software for quality control, sequence assembly, gene prediction, redundancy removal, and abundance calculation. |

| Reference Database | NCBI Non-Redundant (NR) Protein Database [8] | Used for annotating the predicted gene sequences and assigning putative functions. |

| LLW-018 | LLW-018, MF:C35H38Cl2N4O5S, MW:697.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Logmalicid B | Logmalicid B, MF:C21H30O14, MW:506.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Interconnected Microbial Networks and Environmental Impact

Microbial biogeochemical cycling is a complex, interconnected network. Microorganisms often participate synergistically in multiple cycles. For example, in mangroves, genera like Neisseria, Ruegeria, and Desulfotomaculum were found to work together in the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles [7]. This coupling of cycles is a critical aspect of ecosystem functioning.

Human activities and environmental changes significantly impact these microbial drivers and the cycles they control. For instance, shrub expansion in temperate wetlands was shown to alter the abundance of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycle pathways and related functional genes, which may reduce the long-term carbon sequestration potential of these ecosystems [8]. Similarly, the recharge of rivers with reclaimed water, which is often rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, creates a unique and dynamic carbon cycle, promoting algal blooms and altering greenhouse gas fluxes [6]. These disruptions highlight the sensitivity of microbial biogeochemical processes to external pressures. The diagram below illustrates the complex interplay between microbes, elemental cycles, and environmental factors.

The global carbon cycle represents a complex biogeochemical network that regulates the flow of carbon between major Earth systems, including the atmosphere, oceans, terrestrial biosphere, and geological reservoirs. This dynamic cycle plays a fundamental role in controlling planetary climate, with anthropogenic perturbations now creating significant imbalances in natural carbon fluxes. Current assessments indicate that fossil fuel and industrial emissions reached 10.3 ± 0.5 gigatons of carbon per year (GtC yrâ»Â¹) in 2024, with an additional 1.3 ± 0.7 GtC yrâ»Â¹ from land-use changes, totaling 11.6 ± 0.9 GtC yrâ»Â¹ of anthropogenic COâ‚‚ emissions [9]. The atmospheric COâ‚‚ concentration has consequently risen to 422.8 ± 0.1 ppm, approximately 52% above pre-industrial levels [9].

Within this broader context, microbial processes mediate critical transformations between carbon species, particularly in anaerobic environments where methanogenesis occurs. Methane (CHâ‚„) is a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming potential more than 27 times that of COâ‚‚ over a 100-year period [10]. Roughly two-thirds of atmospheric methane emissions originate from microbial activity in oxygen-free environments like wetlands, rice fields, landfills, and the gastrointestinal tracts of ruminants [11]. Understanding the biological mechanisms underlying methane production is therefore essential for accurately quantifying global carbon fluxes and developing targeted mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Major Global Carbon Fluxes (2024 Estimates)

| Flux Component | Symbol | Magnitude (GtC yrâ»Â¹) | Uncertainty (± GtC yrâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil COâ‚‚ Emissions | EFOS | 10.3 | 0.5 |

| Land-Use Change Emissions | ELUC | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Atmospheric Growth Rate | GATM | 7.9 | 0.2 |

| Ocean Sink | SOCEAN | 3.4 | 0.4 |

| Land Sink | SLAND | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| Budget Imbalance | BI | -1.7 | - |

Microbial Methanogenesis: Pathways and Mechanisms

Methanogenesis represents the terminal step in the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter, exclusively performed by archaeal microorganisms known as methanogens. These organisms inhabit an entirely separate branch of the tree of life from bacteria and are essential for completing carbon mineralization in oxygen-depleted environments [11]. The biomethanation process involves a sophisticated microbial food chain wherein fermentative bacteria first decompose complex organic matter to simpler compounds, which are subsequently converted to methane by methanogenic archaea [12].

Major Methanogenic Pathways

Methanogens employ two primary metabolic pathways for methane production, each with distinct substrate requirements and thermodynamic considerations:

CO₂-Reduction Pathway: This hydrogenotrophic pathway involves the reduction of carbon dioxide (or formate) to methane using hydrogen (H₂) or formate as electron donors according to the stoichiometry: 4H₂ + HCO₃⻠+ H⺠→ CH₄ + 3H₂O (ΔG°′ = -135.6 kJ/mol) [12]. This pathway dominates in many environments, including lake sediments where it can account for >95% of total methanogenesis [10].

Aceticlastic Pathway: This acetoclastic pathway involves the cleavage of acetate into methane and carbon dioxide: Acetate⻠+ H⺠→ CH₄ + CO₂ (ΔG°′ = -36.0 kJ/mol) [12]. In most freshwater environments, aceticlastic methanogenesis accounts for approximately two-thirds of methane production, with CO₂-reduction responsible for most of the remaining one-third [12].

Table 2: Major Methanogenic Pathways and Energy Yields

| Pathway | Reaction | ΔG°′ (kJ/mol) | Common Environments |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂-Reduction | 4H₂ + HCO₃⻠+ H⺠→ CH₄ + 3H₂O | -135.6 | Lake sediments, ruminants, natural gas wells |

| Aceticlastic | Acetate⻠→ CH₄ + CO₂ | -36.0 | Wetlands, rice paddies, landfills |

| Formate Reduction | 4Formate⻠+ H⺠+ H₂O → CH₄ + 3HCO₃⻠| -130.4 | Various anaerobic systems |

Both pathways converge on a common set of final enzymatic steps. The methyl group from methyl-tetrahydromethanopterin (CH₃-H₄MPT) is transferred to coenzyme M (HS-CoM) via a membrane-bound methyltransferase complex (Mtr), generating a sodium ion gradient [12]. The terminal reaction is catalyzed by methyl-coenzyme M reductase (Mcr), which reduces the methyl group of CH₃-S-CoM to methane using coenzyme B (HS-CoB) as the electron donor, producing the heterodisulfide CoM-S-S-CoB as a byproduct [12]. The crystal structure of Mcr reveals two active sites, each containing a nickel-containing cofactor (F430) essential for catalysis [12].

Diagram 1: Microbial Methanogenesis Workflow

Advanced Research: Isotopic Fingerprinting and Environmental Controls

A groundbreaking approach to tracing methane origins involves analyzing the stable isotopic composition of carbon (¹²C vs. ¹³C) and hydrogen (¹H vs. ²H) in methane molecules, which provides distinctive "fingerprints" for different environmental sources [11]. Natural gas from geological deposits, methane from cow guts, and methane produced in deep-sea sediments each exhibit characteristic isotopic signatures [11]. Recent research has demonstrated that the isotopic composition of microbial methane is not solely determined by substrate type but is significantly influenced by environmental conditions and cellular responses to substrate availability [11].

UC Berkeley researchers have employed CRISPR gene editing to manipulate the expression of methyl-coenzyme M reductase (Mcr) in Methanosarcina acetivorans, revealing that when this key enzyme is present at low concentrations, cellular metabolism undergoes significant reorganization [11]. Under these conditions, methane production slows dramatically, and enzymatic reactions begin operating in reverse, leading to increased hydrogen exchange between carbon intermediates and ambient water [11]. This exchange progressively alters the hydrogen isotopic signature of methane to more closely reflect that of environmental water rather than the original food source, challenging traditional assumptions about isotopic fingerprints [11].

Environmental Modulation of Methanogenic Communities

Methanogenic pathways and community structures exhibit remarkable consistency across diverse environments with varying organic matter compositions. Research in Lake Geneva sediments demonstrated that COâ‚‚-reduction dominates methane production (>95%) in both profundal and deltaic locations, despite significant differences in organic matter sources and diagenetic states [10]. Molecular analyses revealed that members of the COâ‚‚-reducing Methanoregula genus dominated both sites, indicating that organic matter quality exerts less influence on methanogenic pathway selection than previously assumed [10].

In ruminant systems, methanogenesis inhibition strategies using compounds like 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) have demonstrated the remarkable metabolic plasticity of microbial communities. Supplementation with 3-NOP reduced methane emissions by 62% in dairy calves and triggered a substantial remodeling of the rumen microbiota, characterized by a strong reduction in methanogens and stimulation of reductive acetogens, particularly uncultivated lineages like "Candidatus Faecousia" [13]. However, this intervention also induced a shift in major fermentative communities away from acetate production in response to hydrogen accumulation, resulting in net hydrogen build-up that limited potential productivity gains [13].

Experimental Methodologies in Methanogenesis Research

Isotopic Tracing and Molecular Manipulation

The integration of molecular biology with isotope geochemistry has opened new avenues for investigating methanogenesis. The following protocol outlines key methodological approaches for probing the relationship between microbial physiology and methane isotopic signatures:

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Based Enzyme Manipulation and Isotopic Analysis

CRISPR Gene Editing in Methanogens:

- Utilize CRISPR tools developed for methanogens to dial down expression of the mcrA gene encoding methyl-coenzyme M reductase (Mcr) [11].

- Transform methanogens (e.g., Methanosarcina acetivorans) with CRISPR constructs targeting regulatory sequences of mcrA.

Culture Under Defined Conditions:

- Grow CRISPR-edited and wild-type methanogens under standardized conditions with acetate and methanol as substrates [11].

- Monitor growth curves and methane production rates using gas chromatography.

Isotopic Composition Analysis:

- Collect produced methane using gas-tight sampling systems.

- Analyze carbon (δ¹³C) and hydrogen (δ²H) isotopic compositions using isotope-ratio mass spectrometry.

- Compare isotopic signatures between engineered and wild-type strains to quantify enzymatic effects.

Metabolic Flux Analysis:

- Develop computer models of metabolic networks in methanogens [11].

- Integrate isotopic measurements with model predictions to identify key branch points in methanogenic pathways.

Environmental Sampling and Rate Measurements

Field-based studies of methanogenesis require specialized sampling and incubation techniques to preserve natural redox conditions and microbial activities:

Protocol 2: Sediment Core Processing and Methanogenesis Assays

Sample Collection:

- Collect sediment cores using gravity corers (6.5-14 cm inner diameter) from study sites [10].

- Maintain anaerobic conditions during retrieval and transport.

Porewater Extraction:

- Extract sediment porewater using Rhizon samplers connected to syringes through pre-drilled holes in core liners [10].

- Process samples for dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), acetate, and other volatile fatty acids without headspace.

Radiotracer Rate Measurements:

- Conduct methanogenesis rate measurements using ¹â´C-labeled bicarbonate and acetate [10].

- Incubate sediment slurries under anaerobic conditions with radiotracers.

- Quantify radiolabeled methane production using liquid scintillation counting.

Molecular Analyses:

- Extract DNA/RNA from sediment samples for quantitative PCR of mcrA genes and 16S rRNA sequencing [10].

- Analyze methanogen community structure and abundance correlations with process rates.

Diagram 2: Methanogenesis Research Integration

Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Methanogenesis Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Genetic manipulation | Targeted reduction of enzyme expression | Dialing down MCR activity in Methanosarcina [11] |

| ¹â´C-Labeled Bicarbonate/Acetate | Process rate measurement | Radiotracer for methanogenesis pathways | Quantifying COâ‚‚-reduction vs aceticlastic pathways [10] |

| mcrA Primers | Molecular ecology | Amplification of methanogen functional genes | Quantifying methanogen abundance in environments [10] |

| 3-Nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) | Methanogenesis inhibition | Targeting methyl-CoM reductase | Rumen methane mitigation studies [13] |

| Rhizon Samplers | Porewater extraction | Non-destructive soil solution collection | Obtaining porewater for geochemical analysis [10] |

| Stable Isotope Probes | Metabolic tracking | Identifying active microbial populations | Linking taxa to methane production processes |

The integration of molecular biology, isotope geochemistry, and microbial ecology has dramatically advanced our understanding of methanogenesis within the global carbon cycle. The pioneering work using CRISPR to manipulate key methanogenic enzymes has revealed that isotopic signatures of methane are not merely passive indicators of substrate type but are dynamically shaped by cellular responses to environmental conditions [11]. This finding has profound implications for interpreting methane sources and sinks across diverse ecosystems, from wetland sediments to ruminant digestive systems.

Future research directions will likely focus on harnessing this knowledge to develop targeted strategies for mitigating methane emissions while maintaining critical ecosystem functions. The demonstration that methanogenesis inhibition in ruminants stimulates alternative hydrogenotrophic pathways [13] suggests that microbial community engineering could potentially redirect carbon and electron flow toward valuable products rather than greenhouse gases. Similarly, the detailed understanding of methanogenic pathways in natural gas reservoirs [14] opens possibilities for enhancing biogenic methane production as an energy resource while potentially sequestering COâ‚‚. As methodological innovations continue to bridge disciplinary divides between molecular biology and biogeochemistry, our capacity to predict and manage methane fluxes within the evolving carbon cycle will undoubtedly strengthen.

The nitrogen cycle represents a cornerstone of global biogeochemical processes, primarily orchestrated by microbial entities that transform nitrogen between its various redox states. Framed within a broader context of microbial-mediated elemental cycles, the metabolic versatility of prokaryotes drives the flux of nitrogen through fixation, nitrification, and denitrification pathways. These interconnected processes not only regulate ecosystem productivity but also influence climate feedback mechanisms through the production and consumption of greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxide (Nâ‚‚O). The sophisticated enzymatic machinery possessed by microorganisms enables them to exploit nitrogen compounds as energy sources, electron acceptors, and cellular building blocks, creating a complex network of biogeochemical interactions that span aerobic and anaerobic environments. Recent discoveries, including complete ammonia-oxidizing (comammox) bacteria and novel pathways like direct ammonia oxidation to nitrogen gas (dirammox), have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of nitrification, revealing greater complexity in the microbial partitioning of these metabolic functions [15]. This technical guide synthesizes current understanding of the core nitrogen transformations, emphasizing the microbial actors, their genetic potential, and the experimental frameworks used to quantify these processes within the broader context of carbon and sulfur cycling.

Microbial Catalysts of Nitrogen Transformation

Functional Guilds and Their Metabolic Niches

Microbial specialists catalyze each step of the nitrogen cycle through substrate-specific enzymatic reactions that are often constrained by redox conditions. Nitrogen-fixing diazotrophs utilize the oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase complex to reduce atmospheric Nâ‚‚ to ammonia (NH₃), a process that demands substantial energy investment and occurs in either free-living forms (e.g., Azotobacter, Clostridium) or symbiotic associations (e.g., Rhizobium within legume root nodules). Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and archaea (AOA) initiate nitrification by converting ammonia to hydroxylamine (NHâ‚‚OH) then to nitrite (NOâ‚‚â») via the ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) and hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) enzymes, operating optimally under aerobic conditions [16]. The recent discovery of comammox Nitrospira bacteria, which complete full nitrification (NH₃ to NO₃â») within single organisms, has challenged the traditional two-step nitrification paradigm and revealed previously overlooked metabolic flexibility in nitrifying communities [15]. Denitrifying microorganisms constitute a phylogenetically diverse group including Pseudomonas, Paracoccus, and Thiobacillus species that sequentially reduce nitrate (NO₃â») to nitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚) via nitrite (NOâ‚‚â»), nitric oxide (NO), and nitrous oxide (Nâ‚‚O) as intermediate products, using these transformations as terminal electron acceptors during anaerobic respiration [17].

Table 1: Key Microbial Functional Guilds in the Nitrogen Cycle

| Functional Guild | Primary Metabolic Role | Key Genera | Optimal Environmental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen-fixing bacteria | Reduce N₂ to NH₃ | Rhizobium, Azotobacter, Anabaena | Low O₂, available organic carbon, neutral pH |

| Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria | Oxidize NH₃ to NO₂⻠| Nitrosomonas, Nitrosospira | Aerobic, 7.5-8.5 pH, 20-30°C |

| Ammonia-oxidizing archaea | Oxidize NH₃ to NO₂⻠| Nitrosopumilus, Nitrososphaera | Aerobic, low nutrient, 22-29°C |

| Comammox bacteria | Oxidize NH₃ to NO₃⻠| Nitrospira | Low ammonium, aerobic |

| Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria | Oxidize NO₂⻠to NO₃⻠| Nitrobacter, Nitrospina | Aerobic, 7.5-8.5 pH |

| Denitrifying bacteria | Reduce NO₃⻠to N₂ | Pseudomonas, Paracoccus, Alcaligenes | Anoxic, organic carbon, 30-35°C |

Genomic and Metabolomic Features

The genomic architecture of nitrogen-cycling microorganisms reveals conserved functional genes that serve as molecular markers for process potential and microbial presence. Ammonia monooxygenase genes (amoA) distinguish AOA and AOB, with distinct evolutionary lineages reflecting their adaptation to different environmental conditions [18]. Denitrification involves a suite of metalloenzymes encoded by nap/nar (nitrate reductase), nirK/nirS (nitrite reductase), norB (nitric oxide reductase), and nosZ (nitrous oxide reductase) genes, with the complement of these genes determining the completeness of the denitrification pathway in different microbial taxa [17] [19]. Recent metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches have revealed substantial diversity within these genetic markers, with environmental conditions selecting for specific phylogenetic clusters. For instance, studies of isohumosols (Chernozems) have demonstrated that soil depth and available phosphorus content strongly influence the abundance of nitrification (comammox, AOA amoA, AOB amoA) and denitrification (nirK, nirS, nosZ) genes, with a pronounced depth-dependent decline in abundance and distinct stratification between semi-arid (Ustic) and humid (Udic) soil types [19]. Metabolomic investigations further reveal that microbial nitrogen transformations are coupled to central carbon metabolism through metabolites such as amino acids, organic acids, and carbohydrates, which serve as both energy sources and biosynthetic precursors [20].

Quantitative Process Rates and Environmental Drivers

Methodologies for Quantifying Nitrogen Transformation Rates

Advanced methodologies have enabled precise quantification of gross nitrogen transformation rates in environmental samples. ¹âµN isotopic tracing techniques, employing either ¹âµNH₄⺠or ¹âµNO₃â», allow researchers to track the fate of nitrogen through different pools and calculate process rates based on isotope dilution or enrichment principles [21]. Robotic incubation systems (e.g., Robot and Roflow) enable high-throughput measurements of nitrogen flux under controlled conditions, while membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS) provides sensitive detection of gaseous nitrogen products (Nâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚O) without headspace extraction [15]. Static chamber methods coupled with gas chromatography remain widely used for measuring Nâ‚‚O production potentials from soil and sediment samples, typically involving anaerobic incubation of samples followed by periodic headspace sampling [20]. Potential nitrification rate (PNR) measurements quantify the maximum ammonia oxidation capacity of microbial communities by amending samples with ammonium substrates and measuring nitrate/nitrite accumulation, often using KClO₃ to inhibit the second nitrification step [19]. Similarly, potential denitrification rate (PDR) assays measure the capacity for nitrate reduction under anaerobic conditions with excess carbon and nitrate to eliminate substrate limitations [19].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Investigating Nitrogen Cycle Processes

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Target Process | Detection Limits/Precision | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracer Methods | ¹âµN pool dilution, ¹âµN tracing models | Gross N mineralization, nitrification, denitrification | nmol N·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ | Quantifying simultaneous fluxes in complex systems |

| Gas Flux Measurements | Static chamber with GC, MIMS | Denitrification, nitrifier denitrification | 0.1-100 nmol N·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ | Field-based measurements, process partitioning |

| Molecular Approaches | qPCR of functional genes, metatranscriptomics | Microbial abundance and potential activity | Gene copies: 10²-10¹Ⱐgâ»Â¹ soil | Linking microbial presence to process rates |

| Enzyme Assays | Potential nitrification/denitrification rates | Process capacities under optimal conditions | μmol N·gâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ | Comparing sites, treatment effects |

| Metabolomic Profiling | LC-MS/MS of soil metabolites | Nitrogen metabolite fluxes | pmol-mmol gâ»Â¹ | Pathway identification, microbial metabolism |

Environmental Modulators of Process Rates

Nitrogen transformation rates respond dynamically to abiotic and biotic factors that regulate microbial activity and enzyme kinetics. Oxygen availability represents a primary control, with nitrification generally inhibited below 2 mg/L dissolved oxygen while denitrification is stimulated under anoxic conditions [16]. Soil pH strongly influences the composition of nitrifying communities, with AOA typically dominating in acidic soils and AOB in neutral to alkaline environments, while denitrification efficiency decreases significantly below pH 6.0 [19]. Temperature regulates reaction rates through its effect on enzyme activity, with nitrification optima between 20-30°C and denitrification optima between 30-35°C [16]. Carbon quantity and quality directly impact denitrification capacity by providing essential electron donors, with simple organic compounds (e.g., glucose, acetate) supporting higher rates than complex substrates [20]. Surprisingly, recent research has identified available phosphorus as a key regulator of nitrogen cycling genes in some systems, with significant positive correlations between AP and the abundance of comammox, AOB amoA, nirK, nirS, and nosZ genes in isohumosols, explaining 61% and 21% of the variation in potential nitrification and denitrification rates, respectively [19]. Moisture content and redox potential interact to create microaerophilic niches that simultaneously support both nitrification and denitrification, particularly in aggregated soils and suspended particulate matter in aquatic systems [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for Nitrogen Cycle Investigations

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nitrogen Cycle Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ¹âµN-labeled substrates (K¹âµNO₃, (¹âµNHâ‚„)â‚‚SOâ‚„) | Isotopic tracing of nitrogen pathways | Quantifying gross transformation rates, partitioning Nâ‚‚O sources | ≥98 atom% ¹âµN purity; typically used at 5-50 atom% enrichment |

| Chlorate inhibition reagents (KClO₃, NaClO₃) | Selective inhibition of nitrite oxidation | Measuring potential ammonia oxidation rates without NO₃⻠accumulation | 1-10 mM final concentration; potential non-target effects at high doses |

| DNA extraction kits (e.g., Tiangen magnetic bead kits) | Nucleic acid purification from complex matrices | Molecular analysis of functional genes and microbial community structure | Yield and purity critical for downstream PCR applications |

| qPCR/primer sets for functional genes (amoA, nirS, nirK, nosZ) | Quantification of microbial functional potential | Linking process rates to genetic capacity in environmental samples | Primer selection critical for comprehensive coverage of target groups |

| LC-MS/MS metabolomics reagents | Extraction and analysis of nitrogen metabolites | Profiling amino acids, organic acids, and other N-containing metabolites | 80% methanol extraction; requires internal standards for quantification |

| Continuous flow analyzers (e.g., SAN++) | Automated determination of NHâ‚„âº, NOâ‚‚â», NO₃⻠| High-throughput analysis of inorganic nitrogen species in extracts | Detection limits ~0.1 μM; enables processing of large sample sets |

| Acetylene inhibition reagents (Câ‚‚Hâ‚‚) | Blockade of ammonia monooxygenase and nitrous oxide reductase | Distinguishing nitrification vs. denitrification-derived Nâ‚‚O | 0.01-1.0% v/v; affects other microbial processes at higher concentrations |

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Coupled Process Studies in Terrestrial Systems

Research on agricultural nitrogen cycling exemplifies integrated approaches to understanding coupled biogeochemical processes. A recent study on straw return practices employed a multi-annual positioning experiment with continuous maize cultivation and fallow systems to elucidate how carbon amendments influence nitrogen dynamics [20]. The experimental workflow involved: (1) establishing controlled field plots with and without straw incorporation; (2) periodic soil sampling across depth profiles; (3) comprehensive analysis of soil nitrogen pools (total N, NHâ‚„âº, NO₃â», organic N fractions); (4) quantification of functional gene abundance via qPCR; (5) metabolic profiling using LC-MS/MS; and (6) determination of process rates through incubation experiments. This integrated approach revealed that straw return facilitates nitrogen availability by altering metabolic distribution and nitrogen cycling processes, specifically enhancing metabolic pathways for arginine biosynthesis and amino acid metabolism while increasing the abundance of nitrogen-fixing bacteria like Bradyrhizobium and Altererythrobacter despite reducing the relative abundance of nitrifying microorganisms [20].

Diagram 1: Straw Return Influence on Soil Nitrogen Dynamics (Title: Straw Effects on N Cycle)

Aquatic Nitrogen Transformation Studies

Investigations of marine nitrogen cycling employ sophisticated incubation designs to capture process dynamics across redox gradients. A study on suspended particulate matter (SPM) in Jiaozhou Bay demonstrated how particle-associated microenvironments influence denitrification potential in oxygenated waters [21]. The experimental protocol included: (1) collection of sediment cores and overlying water from estuarine and bay mouth stations; (2) simulation of different SPM concentrations (50-400 mg/L) in laboratory incubations; (3) measurement of denitrification rates using ¹âµNO₃⻠tracing techniques with membrane inlet mass spectrometry; (4) quantification of denitrification genes (narG, nirS) via real-time PCR; and (5) correlation of process rates with environmental parameters. This approach revealed that denitrification rates and functional gene abundances increased with SPM concentration, indicating that suspended particles create anoxic microsites that expand the spatial domain of denitrification in coastal ecosystems, with significant implications for nitrogen removal and eutrophication control [21].

Diagram 2: SPM Effects on Aquatic Denitrification (Title: SPM Enhances Denitrification)

Interconnections with Carbon and Sulfur Cycling

The nitrogen cycle does not operate in isolation but rather intersects profoundly with carbon and sulfur transformations through microbial metabolic networks. Chemoautotrophic nitrifiers couple ammonia oxidation to carbon fixation via the Calvin cycle, contributing to primary production in dark environments while simultaneously acidifying their surroundings through proton release [16]. Denitrifying microorganisms utilize organic carbon compounds as electron donors during anaerobic respiration, creating a direct stoichiometric linkage between carbon oxidation and nitrogen reduction that typically requires a C:N ratio of 1-2 for complete denitrification [17]. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria such as Thiobacillus denitrificans couple denitrification to sulfide oxidation, simultaneously removing reduced sulfur compounds and nitrate while generating acidity that influences nutrient bioavailability [16]. These cross-element interactions create complex feedback loops wherein, for example, the organic carbon added through agricultural practices like straw amendment stimulates denitrification while also enhancing nitrogen fixation through heterotrophic diazotrophs [20]. Understanding these interconnected cycles is essential for predicting ecosystem responses to anthropogenic perturbations and designing effective environmental management strategies.

Emerging Research Frontiers and Methodological Innovations

The field of nitrogen cycle research is rapidly advancing through the application of novel technologies and conceptual frameworks. High-resolution isotopic techniques now enable tracing of nitrogen fluxes at molecular levels, revealing pathway-specific transformations within complex microbial communities [15]. Single-cell metabolomics provides insights into the functional heterogeneity of nitrogen-cycling microorganisms, while nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) allows visualization of isotopic incorporation at the subcellular level [15]. The discovery of comammox bacteria has fundamentally altered nitrification models and prompted re-examination of nitrification control mechanisms in various ecosystems, with evidence suggesting these complete nitrifiers dominate under low-ammonium conditions [15]. Integrated modeling approaches that couple human and natural systems (CHANS), combined with remote sensing and artificial intelligence, now enable high-resolution tracking of nitrogen flows across scales from individual microbial habitats to regional landscapes [15]. These advances are increasingly applied to develop sustainable nitrogen management strategies such as Integrated Soil-Crop System Management (ISSM) and Nitrogen Credit Systems (NCS) that balance agricultural productivity with environmental protection [15]. Future research directions include incorporating microbial processes into large-scale biogeochemical models, engineering microbial communities for enhanced nitrogen use efficiency, and developing early warning systems for nitrogen-related ecosystem perturbations.

The microbial sulfur cycle is a critical component of Earth's biogeochemical systems, intimately linked with the cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and other essential elements [22]. Sulfur, the tenth most abundant element in the universe and the sixth most abundant in microbial biomass, exhibits a wide range of stable redox states that facilitate its role in central biochemistry as a structural element, redox center, and carbon carrier [22]. This technical guide examines the biological mediation of sulfur transformations, with particular emphasis on the microorganisms and molecular mechanisms that drive sulfur oxidation and reduction processes across diverse environments. Understanding these processes is fundamental to modeling biogeochemical cycles and harnessing microbial capabilities for environmental biotechnology [23].

Microbial transformation of both inorganic and organic sulfur compounds has profoundly influenced the properties of the biosphere throughout Earth's history and continues to affect contemporary geochemistry [22]. Recent advances in molecular techniques have revealed novel metabolic pathways and characterized the organisms that facilitate them, fundamentally changing our understanding of microbially driven biogeochemical cycles [22]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of these processes, framed within the context of a broader thesis on the role of microbes in biogeochemical cycles, with specific relevance to researchers and scientists investigating microbial ecology, biogeochemistry, and environmental biotechnology.

Microbial Mechanisms of Sulfur Oxidation

Key Microbial Taxa and Their Metabolic Pathways

Sulfur oxidation refers to the process by which microorganisms oxidize reduced sulfur compounds to obtain energy, often supporting autotrophic carbon fixation [24]. This process is primarily carried out by chemolithoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing prokaryotes, which use compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S), elemental sulfur (Sâ°), thiosulfate (Sâ‚‚O₃²â»), and sulfite (SO₃²â») as electron donors [24]. The oxidation of these substrates is typically coupled to the reduction of oxygen (Oâ‚‚) or nitrate (NO₃â») as terminal electron acceptors, though under anaerobic conditions, some sulfur-oxidizing bacteria can use alternative oxidants [24].

Several key microbial groups involved in sulfur oxidation include genera such as Beggiatoa, Thiobacillus, Acidithiobacillus, and Sulfurimonas, each adapted to specific redox conditions and environmental niches [24]. Metabolic pathways like the Sox (sulfur oxidation) system, reverse dissimilatory sulfite reductase (rDSR) pathway, and the SQR (sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase) pathway serve as central mechanisms through which these microbes mediate sulfur transformations [24].

Table 1: Major Sulfur-Oxidizing Microorganisms and Their Characteristics

| Microbial Group | Metabolic Type | Electron Donors | Electron Acceptors | Environmental Niches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiobacillus spp. | Chemolithoautotroph | Hâ‚‚S, Sâ°, Sâ‚‚O₃²⻠| Oâ‚‚, NO₃⻠| Terrestrial, freshwater |

| Beggiatoa spp. | Chemolithoautotroph, Mixotroph | H₂S, SⰠ| O₂, NO₃⻠| Marine sediments, sulfidic environments |

| Acidithiobacillus spp. | Chemolithoautotroph | Sâ°, Sâ‚‚O₃²⻠| Oâ‚‚ | Acidic environments |

| Sulfurimonas spp. | Chemolithoautotroph | Hâ‚‚S, Sâ°, Sâ‚‚O₃²⻠| NO₃â», Oâ‚‚ | Hydrothermal vents, oxygen minimum zones |

| Purple Sulfur Bacteria | Phototroph | Hâ‚‚S, Sâ° | Light (anaerobic) | Anoxic aquatic layers |

| Green Sulfur Bacteria | Phototroph | Hâ‚‚S, Sâ° | Light (anaerobic) | Anoxic aquatic layers |

| Cable Bacteria | Electrogenic | Hâ‚‚S | Oâ‚‚ (via electron conduction) | Marine sediments |

Ecological Adaptations of Sulfur-Oxidizing Microorganisms

Sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms (SOM) have developed sophisticated adaptations to thrive across environmental gradients. In marine sediments, where concentrations of oxygen, nitrate, and sulfide are typically separated in depth profiles, many SOM cannot directly access their electron sources (reduced sulfur species) and terminal electron acceptors (Oâ‚‚ or nitrate) simultaneously [24]. This limitation has led to remarkable evolutionary innovations:

Large sulfur bacteria (LSB) of the family Beggiatoaceae, particularly model gradient organisms like Beggiatoa, internally store large amounts of nitrate and elemental sulfur to overcome spatial separation between electron donors and acceptors [24]. Some filamentous species can glide between oxic/suboxic and sulfidic environments, while non-motile species rely on nutrient suspensions, fluxes, or attachment to larger particles [24]. Some aquatic, non-motile LSB represent the only known free-living bacteria utilizing two distinct carbon fixation pathways: the Calvin-Benson cycle and the reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle [24].

Electrogenic sulfur oxidation (e-SOx) represents another sophisticated adaptation, recently discovered in filamentous "cable bacteria" [24]. These organisms form multicellular bridges that connect sulfide oxidation in anoxic sediment layers with oxygen or nitrate reduction in oxic surface sediments, generating electric currents over centimeter-long distances [24]. Cable bacteria belong to the family Desulfobulbaceae and are currently represented by two candidate genera, "Candidatus Electronema" and "Candidatus Electrothrix" [24]. This process significantly influences elemental cycling at aquatic sediment surfaces, including iron speciation [24].

Symbiotic relationships between SOM and motile eukaryotic organisms represent another evolutionary strategy, where symbiotic SOM provide carbon and sometimes bioavailable nitrogen to hosts in exchange for enhanced resource access and shelter [24]. This lifestyle has evolved independently in sediment-dwelling ciliates, oligochaetes, nematodes, flatworms, and bivalves [24].

Microbial Reduction of Sulfur Compounds

Sulfate-Reducing Microorganisms and Their Metabolic Diversity

Sulfate reduction represents the reductive branch of the sulfur cycle, primarily carried out by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and archaea in anoxic environments. These microorganisms utilize sulfate (SO₄²â») as a terminal electron acceptor during anaerobic respiration, coupling its reduction to the oxidation of organic compounds or hydrogen [22]. The process results in the production of hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) as a waste product, which profoundly influences the chemistry and ecology of sedimentary environments.

SRB exhibit remarkable metabolic flexibility, utilizing diverse electron donors including lactate, acetate, propionate, fatty acids, and hydrogen [22]. This metabolic versatility enables SRB to occupy diverse ecological niches from marine sediments to the human gut. The energy metabolism and electron flow in sulfate-reducing bacteria have been extensively studied, revealing complex regulatory mechanisms that allow these organisms to adapt to fluctuating environmental conditions [22].

Table 2: Sulfur Reduction Processes and Associated Microorganisms

| Reduction Process | Reduced Product | Key Microorganisms | Environmental Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissimilatory Sulfate Reduction | Hâ‚‚S | Desulfovibrio, Desulfobacter, Desulfobulbus | Major pathway in marine sediments, accounts for ~50% of organic matter mineralization in anoxic marine environments |

| Assimilatory Sulfate Reduction | Organic sulfur compounds | Most microorganisms | Incorporation of sulfur into biomass (cysteine, methionine) |

| Sulfite Reduction | Hâ‚‚S | Desulfovibrio, Desulfotomaculum | Intermediate in sulfate reduction pathway |

| Elemental Sulfur Reduction | Hâ‚‚S | Desulfuromonas, Wolinella | Important in hypersaline environments, synergistic relationships with phototrophic sulfur oxidizers |

Environmental Significance of Sulfur Reduction

Sulfate reduction plays a crucial role in organic matter mineralization, particularly in marine sediments where sulfate is abundant [22]. Sulfate-reducing microorganisms are responsible for approximately 50% of organic carbon mineralization in anoxic marine sediments, making them key players in carbon cycling [22]. The sulfide produced through sulfate reduction can precipitate with iron minerals to form iron sulfides (FeS) or pyrite (FeSâ‚‚), effectively removing sulfur from biological cycling and influencing iron availability [24].

In extreme environments such as soda lakes, which combine high salinity with high pH, sulfidogenesis exhibits unique characteristics with implications for both the reductive and oxidative arms of the sulfur cycle [22]. Recent research has provided new insights into sulfidogenesis in these fascinating systems, expanding our understanding of the limits of microbial sulfur cycling [22].

Methodologies for Studying Microbial Sulfur Cycling

Experimental Approaches and Analytical Techniques

Research in sulfur microbiology employs diverse methodologies spanning molecular biochemistry of single enzymes to community-level metagenomics and metatranscriptomics [22]. The following experimental protocols represent key approaches for investigating microbial sulfur transformations:

Enzyme Activity Assays: Structural and functional analyses of sulfur-transforming enzymes provide fundamental insights into catalytic mechanisms. Recent structural analyses have been reported for disproportionating sulfur oxygenase/reductase and dissimilatory sulfite reductase [22]. Independent studies have focused on tetrathionate hydrolase of both bacterial and archaeal origin, while electron flow for the Sor pathway of thiosulfate oxidation has been further defined in Sinorhizobium meliloti [22]. Functional evidence in phototrophic bacteria has demonstrated the role of quinone-interacting membrane-bound oxidoreductase in sulfite oxidation [22].

Stable Isotope Probing: Using ¹³C-labeled carbon dioxide or ³âµS-labeled sulfate allows researchers to track carbon fixation by chemolithoautotrophic sulfur oxidizers or sulfur transformations in complex environments. Isotope tracing experiments have been crucial for examining substrate exchange in symbiotic associations [22].

Molecular Ecological Analyses: Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches enable characterization of microbial community structure and gene expression patterns without cultivation. Transcriptomic analysis of uncultured microbial symbionts has provided insights into their metabolic capabilities and interactions with hosts [22]. Quantitative PCR targeting functional genes such as dsrAB (dissimilatory sulfite reductase) and soxB (sulfur oxidation) allows quantification of specific microbial groups involved in sulfur cycling [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Microbial Sulfur Cycling

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Later | Aqueous, non-toxic storage solution | Preserves RNA integrity in environmental samples for transcriptomic studies of sulfur cycling genes |

| SYBR Green/Probes | Fluorescent nucleic acid stains | Detection and quantification of functional genes (e.g., dsrB, soxB) in qPCR assays |

| ³âµS-Labeled Sulfate | Radiotracer with ³âµS isotope | Tracing sulfate reduction pathways and rates in sediment incubations |

| ¹³C-Labeled Bicarbonate | Stable isotope-labeled inorganic carbon | Tracking autotrophic carbon fixation by chemolithoautotrophic sulfur oxidizers |

| Tetrathionate | K₂S₄O₆ or Na₂S₄O₆ | Substrate for studying tetrathionate hydrolase activity in sulfur oxidizers |

| Sulfide-Specific Microsensors | Glass microelectrodes with sulfide-sensitive chemistry | High-resolution measurement of sulfide gradients in microbial mats and sediments |

| Anoxic Culture Media | Pre-reduced media with resazurin indicator | Culturing anaerobic sulfur-reducing microorganisms |

| DAPI Stain | 4',6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dye | Total cell counting and visualization of microbial communities in sulfur-rich environments |

| Hydroxychloroquine-d5 | Hydroxychloroquine-d5, MF:C22H30ClN3O9, MW:521.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stat6-IN-5 | Stat6-IN-5, MF:C26H24F3N7O3S, MW:571.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Environmental Significance and Applications

Biogeochemical Cycling and Ecosystem Functioning

Microbial sulfur cycling plays a fundamental role in biogeochemical processes across diverse environments, from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to terrestrial soils [22] [24]. In marine systems, sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms are particularly important in environments where abundant reduced sulfur species coexist with low oxygen concentrations, including marine sediments, hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, sulfidic caves, oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), and stratified water columns [24]. Through their metabolic versatility and ecological distribution, sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms help maintain redox balance and influence the chemistry of their surrounding environments, supporting broader ecosystem functioning [24].

The competition between biological and abiotic sulfur oxidation has significant environmental implications. While iron-mediated oxidation of sulfide to iron sulfide (FeS) or pyrite (FeSâ‚‚) occurs abiotically [24], thermodynamic and kinetic considerations suggest that biological oxidation far exceeds chemical oxidation in most environments [22]. Experimental data indicate that microorganisms may enhance sulfide oxidation by three or more orders of magnitude compared to abiotic processes [24]. This biological dominance stems from kinetic restrictions on abiotic oxidation, meaning biotic sulfide oxidation almost always occurs at significantly faster rates [22].

Anthropogenic Influences and Environmental Biotechnology

Human activities increasingly influence sulfur cycling through habitat fragmentation, pollution, and urbanization. Recent research demonstrates that habitat fragmentation in urban remnant forests significantly affects microbial functional genes associated with sulfur cycling [25]. Smaller and more isolated forest patches exhibit reduced abundance of key functional genes involved in nutrient cycling, with fragmentation altering microbial community composition and potentially disrupting fundamental ecosystem functions [25]. These findings highlight the vulnerability of soil microbial communities to human-driven landscape changes, with potential consequences for sulfur and other elemental cycles.

The microbial sulfur cycle offers promising applications in environmental biotechnology, including wastewater treatment, soil bioremediation, and toxic pollutant degradation [24]. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria demonstrate particular utility in detoxifying hydrogen sulfide, offering advantages over conventional chemical oxidation methods employing hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), chlorine gas (Clâ‚‚), and hypochlorite (NaClO) [24]. In wastewater treatment, Beggiatoa species effectively oxidize sulfur compounds in microaerophilic up-flow sludge beds and can be combined with nitrogen-reducing bacteria to remove chemical accumulations in industrial settings [24].

In agricultural systems, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria like Thiobacillus thiooxidans can increase soil pH from extremely acidic levels (pH 1.5) to neutral conditions (pH 7.0), while simultaneously increasing phosphorus and sulfur availability for plants [24]. This capability makes SOB valuable for managing alkaline and low-sulfur soils, potentially increasing crop yields in various ecosystems worldwide [24]. Certain SOB also show potential as biotic pesticides and anti-infectious agents for crop protection [24].

Microbial mediation of sulfur oxidation and reduction processes represents a fundamental component of Earth's biogeochemical architecture, with far-reaching implications for ecosystem functioning, climate regulation, and environmental management. The intricate metabolic pathways employed by sulfur-cycling microorganisms, their sophisticated adaptations to environmental gradients, and their complex interactions with other elemental cycles underscore the importance of integrating sulfur microbiology into broader models of Earth system science.

Recent advances in molecular techniques, analytical approaches, and conceptual frameworks have dramatically expanded our understanding of microbial sulfur transformations, revealing novel metabolic capabilities, previously unrecognized microbial groups, and unexpected ecological relationships. This knowledge provides a foundation for harnessing microbial capabilities to address pressing environmental challenges, from wastewater treatment and soil remediation to climate change mitigation.

As research continues to uncover the diversity, mechanisms, and ecological significance of sulfur-cycling microorganisms, integration of this knowledge into interdisciplinary frameworks will be essential for advancing our understanding of Earth's biogeochemical cycles and developing sustainable strategies for environmental management. The microbial sulfur cycle, once a specialized niche within environmental microbiology, now emerges as a central player in the co-evolution of Earth's geosphere and biosphere, with profound implications for the past, present, and future of our planet.

The interplay between sulfur and iron cycles represents one of the most fundamental redox processes in anoxic environments, with profound implications for global biogeochemical cycling. For decades, scientific consensus held that the reaction between hydrogen sulfide and iron(III) oxides occurred exclusively through abiotic mechanisms, producing elemental sulfur and iron monosulfide as intermediate products [26] [27]. This paradigm has been fundamentally reshaped by the recent discovery of Microorganisms that couple Iron Sulfide Oxidation (MISO)—a novel microbial metabolism that directly couples sulfide oxidation to iron(III) oxide reduction [26] [28] [29]. This biological process not only outperforms its chemical counterpart in speed but also follows a distinct pathway that directly generates sulfate, bypassing intermediate sulfur species [26] [27]. The emergence of MISO metabolism reveals a previously overlooked biological mechanism that profoundly connects the cycling of sulfur, iron, and carbon in oxygen-free environments, with far-reaching implications for our understanding of elemental fluxes in marine sediments, wetlands, and aquifers [26] [29].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of MISO Metabolism

| Characteristic | Abiotic Process | MISO Biological Process |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Products | Elemental sulfur, iron monosulfide (FeS) | Sulfate |

| Reaction Rate | Slower at environmentally relevant sulfide concentrations | Faster, biologically catalyzed |

| Energy Capture | Not applicable | Supports microbial growth |

| Carbon Fixation | Not applicable | Autotrophic carbon fixation |

| Global Significance | Limited | ~7% of global sulfide oxidation in marine sediments |

Genomic and Metabolic Foundations of MISO Microorganisms

Phylogenetic Diversity and Distribution

Comprehensive genomic analysis has revealed that the capacity for MISO metabolism spans an astonishing phylogenetic breadth across the microbial world. Through the development of a sophisticated computational framework involving phylogenetic analyses of 116 proteins involved in sulfur redox transformations and hidden Markov models for monophyletic clades, researchers systematically queried 42 key sulfur-cycling enzymes across representative bacterial and archaeal genomes [26]. This analysis demonstrated that more than half of all prokaryotic species encode at least one sulfur-cycling marker protein, with this capability distributed across 120 (80.5%) of 149 known bacterial and archaeal phyla [26]. Most significantly, the co-occurrence of genetic determinants for sulfur compound oxidation and extracellular iron(III) reduction was identified in diverse members of 37 prokaryotic phyla, indicating that MISO metabolism represents a widespread and phylogenetically diverse metabolic strategy [26].

Among the 5,561 species identified with sulfur-cycling potential, many are represented exclusively by genomes from uncultured microorganisms, highlighting the vast unexplored diversity of sulfur-cycling microbes and underscoring the limitation of culture-dependent approaches in characterizing microbial metabolic potential [26]. The genomic potential for MISO metabolism has been identified across diverse environments including marine sediments, terrestrial wetlands, and underground aquifers, suggesting this metabolic strategy provides a competitive advantage across a spectrum of anoxic habitats [26] [27].

Molecular Mechanisms and Metabolic Pathways

Genome-based metabolic reconstructions have elucidated three distinct metabolic options for coupling sulfur oxidation to extracellular iron(III) reduction, each employing different enzymatic systems [26]:

Complete sulfide oxidation to sulfate coupled to iron(III) reduction, employed by organisms like Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus utilizing the reverse dissimilatory sulfite reductase pathway (rDsr) with sulfate adenylyltransferase (Sat) and adenosine-5'-phosphosulfate reductase (AprAB) [26].

Sulfide oxidation to elemental sulfur via sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (Sqr) and FccBA complexes, coupled to iron(III) reduction through MtrCAB-type multi-heme protein complexes, as identified in uncultured Rhodoferax species [26].

Thiosulfate oxidation coupled to iron(III) reduction via MtrCAB systems in known thiosulfate oxidizers within families including Burkholderiaceae, Sulfurifustaceae, and Ectothiorhodospiraceae [26].

The diagram below illustrates the electron transfer pathway for complete sulfide oxidation to sulfate coupled to iron(III) reduction as characterized in Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus:

Diagram 1: MISO Electron Transfer Pathway (Title: MISO Electron Transfer in D. alkaliphilus)

Thermodynamic calculations confirm that all three metabolic reactions provide sufficient energy to support microbial growth, with iron(III)-dependent sulfide oxidation under natural conditions yielding -20 to -40 kJ per mole electron, which exceeds the minimum energy quantum considered necessary for biological energy conservation [26]. This energetic feasibility, combined with the phylogenetic diversity of microorganisms encoding these pathways, explains the widespread distribution and environmental significance of MISO metabolism.

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Physiological Characterization of MISO Activity

The genome-predicted potential for MISO metabolism was experimentally validated using Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus as a model organism, selected based on its genetic repertoire for complete sulfide oxidation coupled to iron(III) reduction [26]. Physiological experiments employed several complementary approaches to demonstrate and quantify MISO activity:

Cultivation Conditions: D. alkaliphilus was grown in anoxic media with ferrihydrite as the sole electron acceptor and either formate, poorly crystalline FeS, or dissolved sulfide as electron donors [26]. The stoichiometry of formate-dependent iron reduction followed the reaction: HCOOâ» + 2Fe(III) → COâ‚‚ + 2Fe(II) + Hâº, confirming the capacity for extracellular solid iron(III) oxide reduction [26].

Analytical Measurements: Iron reduction was quantified by measuring Fe(II) production over time using the ferrozine assay after extraction with 0.5 N HCl [26]. Sulfide oxidation was tracked by monitoring sulfide depletion and sulfate production via ion chromatography. Formate consumption and carbon dioxide production were measured to establish stoichiometric relationships and confirm energy conservation from the coupled redox process [26].

Comparative Rate Measurements: The biological MISO reaction was directly compared to abiotic controls under identical environmental conditions, demonstrating that the enzymatically catalyzed process outpaced the chemical reaction at environmentally relevant sulfide concentrations [26].

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from D. alkaliphilus Cultivation

| Experimental Parameter | Result | Environmental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Donors Supported | Formate, dissolved sulfide, FeS | Metabolic versatility in different environments |

| Iron Reduction Rate | Biologically enhanced | Faster sulfide removal than abiotic processes |

| Growth Coupling | Autotrophic growth demonstrated | Carbon fixation linked to S/Fe cycling |

| Final Sulfur Product | Sulfate | Direct pathway without S(0) accumulation |

| pH Range | Neutral to alkaline | Relevant to diverse natural systems |

Transcriptomic Analysis of MISO Metabolism

To complement physiological experiments and confirm the genetic basis of MISO metabolism, transcriptomic analyses were performed on D. alkaliphilus under iron(III)-reducing conditions with sulfide as the electron donor [26]. This approach revealed:

Differential Gene Expression: Upregulation of genes encoding the reverse dissimilatory sulfite reductase system (rDsrAB) during growth on sulfide and ferrihydrite, confirming the operation of this pathway in the oxidative direction [26].

Electron Transport Components: Significant expression of genes encoding multi-heme c-type cytochromes homologous to those used by Geobacter species for extracellular electron transfer, providing the molecular machinery for electron flow from sulfide to solid-phase iron(III) oxides [26].

Energy Conservation Systems: Expression of genes associated with proton translocation and ATP synthesis, confirming the energy-yielding nature of the MISO process and its capacity to support cellular growth [26].

The transcriptomic data provided conclusive evidence that D. alkaliphilus actively transcribes the genetic machinery necessary for direct electron transfer from sulfide to extracellular iron(III) oxides, validating the metabolic model predicted from genomic analyses.

Environmental Significance and Global Implications

Quantitative Impact on Global Element Cycles

The discovery of MISO metabolism necessitates revision of existing biogeochemical models describing sulfur and iron cycling in anoxic environments. Quantitative assessments suggest that MISO activity in marine sediments could be responsible for approximately 7% of all global sulfide oxidation to sulfate [28] [29] [27]. This significant flux is fueled by the continuous input of reactive iron from rivers and melting glaciers into marine systems, providing a steady supply of electron acceptors for MISO microorganisms [28] [29]. The direct biological oxidation of sulfide to sulfate represents a streamlined pathway that bypasses the intermediate sulfur species characteristic of abiotic reactions, fundamentally altering the expected speciation of sulfur compounds in iron-rich anoxic environments [26] [27].

The coupling of sulfide oxidation to iron reduction also influences carbon cycling through multiple mechanisms. MISO microorganisms like D. alkaliphilus grow autotrophically, fixing carbon dioxide into biomass and thus linking the iron and sulfur cycles to carbon sequestration [26] [27]. Additionally, by controlling sulfide concentrations, MISO bacteria indirectly influence methane emissions, as sulfide toxicity can inhibit methane-consuming archaea in anoxic environments [28] [29].

Ecological Applications and Environmental Protection

Beyond their fundamental biogeochemical importance, MISO microorganisms play crucial roles in maintaining ecosystem health and preventing environmental degradation:

Mitigation of Oceanic Dead Zones: By efficiently removing toxic hydrogen sulfide, MISO bacteria may help prevent the expansion of oxygen-depleted "dead zones" in aquatic ecosystems [28] [29] [27]. Hydrogen sulfide accumulation poses serious threats to aquatic life through direct toxicity and oxygen depletion, and the rapid biological removal of sulfide by MISO microorganisms represents a natural control mechanism that helps maintain ecological balance [28] [29].

Biogeochemical Engineering Applications: The rapid kinetics of biologically catalyzed sulfide oxidation suggest potential applications in engineered systems for treating sulfide-contaminated waters or managing sulfide generation in industrial processes [26]. The ability of MISO microorganisms to immobilize arsenic through iron sulfide oxidation has also been demonstrated in related systems, suggesting potential applications for remediation of heavy metal contamination [30].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methodologies and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for MISO Research

| Reagent/Technique | Function/Application | Example Use in MISO Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrihydrite | Model iron(III) oxide electron acceptor | Physiological experiments with D. alkaliphilus |

| Ferrozine Assay | Quantification of Fe(II) production | Measurement of iron reduction rates |

| Anoxic Cultivation Systems | Maintain oxygen-free conditions | Cultivation of strict anaerobes |

| Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) | Protein family identification | Phylogenetic analysis of sulfur-cycling genes |

| Metagenomic Sequencing | Assessment of microbial community potential | Identification of MISO capacity in uncultured lineages |

| RNA Sequencing | Transcriptome analysis | Verification of gene expression under MISO conditions |

| Ion Chromatography | Sulfate quantification | Tracking sulfide oxidation to sulfate |

| 8-CPT-cAMP-AM | 8-CPT-cAMP-AM, MF:C19H19ClN5O8PS, MW:543.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pde1-IN-9 | Pde1-IN-9, MF:C28H31N3O2, MW:441.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental workflow for investigating MISO metabolism integrates cultivation-based physiological studies with genomic and transcriptomic approaches, as illustrated below:

Diagram 2: MISO Research Methodology (Title: Integrated MISO Research Workflow)

The discovery of MISO metabolism represents a fundamental advance in our understanding of how microorganisms drive Earth's elemental cycles. By demonstrating that sulfide oxidation coupled to iron(III) reduction supports biological energy conservation, this research has revealed a previously overlooked mechanism that shapes global biogeochemical fluxes. The phylogenetic diversity of microorganisms encoding MISA potential, combined with the demonstrated physiological capability in cultivated representatives, establishes this process as a significant component of the Earth's metabolic repertoire.

From a broader perspective, MISO metabolism exemplifies the profound interconnectedness of elemental cycles, demonstrating how microorganisms forge direct links between sulfur, iron, and carbon transformations. This discovery not only expands our fundamental knowledge of microbial metabolism but also reveals new mechanisms for natural ecosystem protection against sulfide toxicity. As research continues to explore the distribution, regulation, and environmental impact of MISO metabolism across diverse ecosystems, our understanding of Earth's biogeochemical engines will continue to evolve, revealing ever-deeper complexity in the microbial processes that sustain our planet's habitability.

Extremophiles and Their Unique Metabolic Contributions

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in physically or geochemically extreme conditions detrimental to most life on Earth [31]. These microorganisms inhabit environments characterized by extreme temperatures, pH values, ionic strength, pressure, or scarce nutrients [31]. The study of extremophiles has gained significant importance due to their remarkable adaptations that enable survival in harsh conditions, their role in biogeochemical cycles, and their potential applications in biotechnology and astrobiology [31] [32].

These resilient organisms play crucial roles in all biogeochemical cycles on Earth, particularly in the nitrogen cycle, which is essential for converting nitrogen into multiple chemical forms that circulate among atmospheric, terrestrial, and aquatic ecosystems [31]. Recent research has revealed that extremophilic microbes, especially members of the Archaea domain, are key players in nitrogen transformations in extreme environments, with potential implications for global warming, nitrogen balance, and biotechnological applications [31].

This review comprehensively examines the classification of extremophiles, their unique metabolic capabilities, their roles in biogeochemical cycles, and the experimental approaches used to study these remarkable organisms, with a particular focus on their contributions to carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling.

Classification of Extremophiles

Extremophiles can be broadly categorized into two groups: extremophilic organisms, which require one or more extreme conditions to grow, and extremotolerant organisms, which can tolerate extreme values of one or more physicochemical parameters though growing optimally at "normal" conditions [31]. In contrast, mesophile refers to microbes growing best in moderate temperatures (typically between 20 and 45°C) and usually at pH between 6 and 8 [31].

Table 1: Classification of Extremophiles Based on Growth Conditions

| Term | Defining Factor | Growth Limits | Examples of Environments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidophile | pH | ≤ 3 | Volcanic lakes, acidic mine drainage [31] |

| Alkaliphile | pH | ≥ 9 | Alkaline/soda lakes, limestone caves [31] [32] |

| Halophile | High salt concentration | 1-4 M | Salt lakes, salt mines [31] [32] |

| Thermophile | High temperature | 45-80°C [33] | Hot springs, geothermally heated soil [33] |

| Hyperthermophile | Very high temperature | >80°C [33] | Deep-sea hydrothermal vents [33] |

| Psychrophile | Low temperature | ≤ -15°C [31] | Polar regions, deep oceans [31] [32] |

| Piezophile (Barophile) | High pressure | ~1100 bar [31] | Deep ocean sediments [31] [32] |

| Radiophile (Radiotolerant) | Ionizing radiation | 1500-6000 Gy [31] | Radioactive environments [31] |

| Xerophile | Desiccating conditions | ≤ 50% relative humidity [31] | Deserts, endolithic habitats [31] [32] |

Some extremophiles are adapted simultaneously to multiple stresses and are classified as "polyextremophiles" [31]. Examples include haloalkalophiles (combining halophilic and alkalophilic profiles with salt concentration between 2-4 M and pH values of 9 or above) and thermoacidophiles (combining thermophilic and acidophilic profiles with temperatures of 70-80°C and pH between 2-3) [31]. The archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, which thrives at pH 3 and 80°C, represents a classic example of a polyextremophile [34].

Although extremophiles include members of all three domains of life, most belong to Archaea, with some archaea representing the most hyperthermophilic, acidophilic, alkaliphilic, and halophilic microorganisms known [31]. For instance, Methanopyrus kandleri strain 116 grows at temperatures up to 122°C, the highest recorded temperature for any organism [31] [33].

Metabolic Capabilities and Biogeochemical Roles

Extremophiles have evolved unique metabolic strategies that enable them to drive biogeochemical cycles under conditions previously considered inhospitable for life. Their activities significantly influence carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling in extreme environments, often through coupled metabolic pathways.

Carbon Cycle Contributions