Microbial Source Tracking Methods: A Comprehensive Comparison for Environmental and Public Health Applications

This article provides a systematic comparison of microbial source tracking (MST) methodologies, addressing critical needs for researchers and environmental health professionals.

Microbial Source Tracking Methods: A Comprehensive Comparison for Environmental and Public Health Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of microbial source tracking (MST) methodologies, addressing critical needs for researchers and environmental health professionals. It explores the foundational principles of MST, detailing the evolution from traditional library-dependent approaches to modern library-independent molecular techniques. The review critically evaluates methodological performance, application-specific considerations, and common optimization challenges. By synthesizing validation frameworks and comparative performance data across multiple studies, this analysis offers evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate MST protocols for water quality investigations, fecal contamination source attribution, and public health risk assessment.

The Evolution and Core Principles of Microbial Source Tracking

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) comprises a group of methodologies aimed at identifying, and in some cases quantifying, the dominant source(s) of fecal contamination in environmental waters [1] [2]. The fundamental purpose of MST is to discriminate between human and nonhuman sources of fecal pollution, with some advanced methods capable of differentiating between contamination originating from specific animal species [1] [3]. This capability is crucial for accurate risk assessment and effective remediation, as human fecal contamination generally presents a greater public health risk due to the likely presence of human-specific enteric pathogens [3].

The development of MST technologies emerged from a critical limitation of traditional fecal indicator bacteria (FIB). While FIB such as E. coli and enterococci have been used for decades to predict the presence of fecal pollution, their ubiquity in the intestines of many warm-blooded animals means they cannot distinguish between different contamination sources [3]. This limitation significantly reduces their effectiveness for risk assessment and remediation planning. MST enhances the utility of these indicators by providing tools to determine their origin, thereby offering water quality managers not just information about if and when fecal contamination is present, but who is contributing to the pollution [1].

Historical Development and Evolution

The field of MST has evolved significantly from its initial concepts to the sophisticated molecular tools available today. Early approaches relied on simple microbiological ratios, notably the fecal coliform/fecal streptococcus ratio, where a ratio of >4.0 was considered indicative of human pollution and ≤0.7 suggested nonhuman sources [3]. However, this method proved unreliable due to variable survival rates of different bacterial species and variations in detection methods, leading to its eventual abandonment as a viable source tracking approach [3].

The 1990s and early 2000s witnessed the development of more sophisticated methodologies, broadly categorized as library-dependent and library-independent methods [1]. Library-dependent methods (LDM) rely on cultivating bacteria from water samples and comparing their phenotypic or genotypic "fingerprints" to extensive libraries of bacterial strains from known fecal sources [1] [2]. In contrast, library-independent methods (LIM) detect specific host-associated genetic markers directly from environmental samples without requiring cultivation or reference libraries [1].

A significant shift in the field has been the move away from culture-based methods toward molecular approaches, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based technologies [4]. This transition was clearly demonstrated in the Source Identification Protocol Project (SIPP), a major multi-laboratory comparison study where, unlike a similar study a decade earlier, nearly all participating laboratories utilized PCR-based methods without cultivation steps [4].

Table: Historical Evolution of Microbial Source Tracking Approaches

| Time Period | Primary Methods | Key Limitations | Major Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Approaches (Pre-1990s) | Fecal coliform/fecal streptococcus ratios [3] | Variable survival rates; unreliable for source identification [3] | Recognition that source identification was possible |

| Library-Dependent Era (1990s-early 2000s) | Ribotyping, Antibiotic Resistance Analysis, PFGE, REP-PCR [1] [5] | Geographic and temporal specificity; labor-intensive; requires large libraries [1] | Development of statistical frameworks for classifying sources |

| Library-Independent Transition (2000s-2010s) | Host-specific PCR markers (e.g., Bacteroidales) [1] [4] | Marker specificity and sensitivity challenges [6] [4] | Direct detection without cultivation; quantitative capabilities |

| Modern Integration (2010s-Present) | qPCR, ddPCR, microbiome analysis, community-based approaches [4] [7] | Standardization needs; matrix effects [4] | Multiplexing; absolute quantification; community profiling |

Classification of MST Methodologies

Library-Dependent Methods

Library-dependent MST methods are culture-based approaches that rely on isolate-by-isolate identification of bacteria cultured from various fecal sources and water samples [1]. These methods involve comparing these isolates to a "library" of bacterial strains from known fecal sources, using either phenotypic or genotypic characteristics for classification [1]. The underlying assumption is that certain strains of fecal bacteria become adapted to specific host animals and can be differentiated based on these adaptations [1].

Table: Common Library-Dependent MST Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribotyping [1] | Southern blot of genomic DNA cut with restriction enzymes; probed with ribosomal sequences [1] | Highly reproducible; classifies isolates from multiple sources [1] | Complex; expensive; labor intensive; geographically specific; database required [1] |

| Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) [1] | DNA fingerprinting with rare-cutting restriction enzymes coupled with electrophoretic analysis [1] | Extremely sensitive to minute genetic differences; highly reproducible [1] | Long assay time; limited simultaneous processing; database required [1] |

| Antibiotic Resistance Analysis (ARA) [5] | Patterns of resistance to various antibiotics used to classify sources [1] | Relatively simple methodology; provides phenotypic information [5] | Influenced by environmental exposure to antibiotics; database required [1] |

| Repetitive DNA Sequences (Rep-PCR) [1] | PCR used to amplify palindromic DNA sequences coupled with electrophoretic analysis [1] | Simple and rapid [1] | Reproducibility concerns; large database required; variability increases with database size [1] |

Library-Independent Methods

Library-independent methods represent a paradigm shift in MST, as they detect specific host-associated genetic markers directly from water samples without requiring cultivation or extensive libraries [1]. These methods primarily utilize polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify gene targets that are specifically associated with particular host populations [1]. The detection of a single host-associated marker is sufficient to indicate the presence of feces from that source, significantly streamlining the analytical process [2].

One of the most significant advancements in library-independent MST has been the development of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) assays that target host-specific genetic markers from bacterial groups such as Bacteroidales [4] [8] [7]. These anaerobic bacteria are particularly suitable for MST applications because they are abundant in the gut microbiome, typically short-lived outside of a host, and exhibit host specificity [7]. Commonly used markers include HF183 for human sources, DogBact for canine contamination, CowM2 for cattle, and LeeSeaGull for gull feces [4] [8] [7].

More recently, microbiome-based approaches using 16S rRNA gene sequencing have emerged, which analyze the entire microbial community composition rather than individual markers [7]. Tools like SourceTracker2 use Bayesian approaches to identify fecal contamination based on comparisons between known source communities and environmental samples [7].

Performance Comparison of MST Methods

Evaluating the performance of various MST methods has been the focus of several multi-laboratory comparison studies. The Southern California Microbial Source Tracking Method Comparison study found that no method perfectly predicted the source material in blind samples, but host-specific PCR performed best at differentiating between human and non-human sources [9]. The study also noted that virus and F+ coliphage methods reliably identified sewage but couldn't detect fecal contamination from individual humans, while library-based methods could identify dominant sources but had issues with false positives [9].

The Source Identification Protocol Project (SIPP), representing the largest multiple-laboratory effort to assess MST methods, identified several top-performing assays based on sensitivity and specificity metrics [4]. For human sources, the HF183 marker demonstrated excellent performance, while CF193 and Rum2Bac were reliable for ruminant sources, CowM2 and CowM3 for cattle, BacCan for dogs, Gull2SYBR and LeeSeaGull for gulls, PF163 and pigmtDNA for pigs, and HoF597 for horses [4].

Table: Performance Characteristics of Selected MST Markers from Multi-Laboratory Studies

| Target Host | Marker | Technology | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | HF183 | qPCR | Varies by study (0.70-1.00) | Varies by study (1.00) | [5] [4] |

| Human | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | PCR | 0.78-0.92 | 0.76-0.98 | [5] |

| Ruminant/Cattle | CF128 | PCR | 0.97-1.00 | 0.73-1.00 | [5] |

| Ruminant/Cattle | CF193 | PCR | 1.00 | 0.70-1.00 | [5] |

| Chicken | CH7 | PCR | 0.67 | 0.779 | [6] |

| Chicken | CH9 | PCR | 0.55 | 0.994 | [6] |

| Dog | DogBact | qPCR | >0.98 | >0.98 (except coyote) | [7] |

Performance validation remains challenging due to geographic variability, environmental matrix effects, and differences in laboratory protocols [4]. Marker performance can vary significantly based on the geographic origin of fecal samples, necessitating local validation before application. Environmental matrices can also inhibit PCR amplification, affecting quantification accuracy [4]. Recent approaches address these challenges through the use of internal controls, standardized extraction methods, and digital PCR platforms that are less susceptible to inhibition [8].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Sample Collection and Processing

Standardized sample collection and processing are critical for reliable MST results. Water samples are typically collected in sterile containers and processed promptly, often following regulatory agency guidelines such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Beach Guidance [2]. For molecular MST methods, samples are typically filtered onto membranes (e.g., 0.2-0.45 μm pore size) to concentrate microbial biomass [7]. Filters are then either processed immediately or frozen at -80°C until DNA extraction can be performed [7].

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

DNA extraction is performed using commercial kits specifically designed for environmental samples, such as the DNeasy PowerWater kit (QIAGEN) [7]. These kits effectively remove PCR inhibitors that are common in environmental matrices. DNA quality and concentration are typically assessed using spectrophotometric methods (e.g., Nanodrop) or fluorometric assays [7]. The inclusion of internal controls and standards helps monitor extraction efficiency and potential inhibition [4].

PCR-Based Detection and Quantification

Most contemporary MST methods utilize some form of PCR for detection and quantification. The basic workflow involves preparing reaction mixtures containing primers, probes, master mix, and sample DNA template [7]. For the HF183 human-associated marker, following EPA Method 1696, each reaction includes specific primers (BacR287 and HF183), a TaqMan probe (BacP234MGB), bovine serum albumin to reduce inhibition, environmental master mix, and sample template [7].

Thermocycling parameters typically include an initial denaturation step (e.g., 95°C for 10 minutes) followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 seconds) and annealing/extension (60°C for 1 minute) [7]. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) provides information about marker concentration, which can be correlated with the extent of contamination, while digital PCR (dPCR) offers absolute quantification without the need for standard curves and is less susceptible to inhibition [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Source Tracking

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Specifications | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex environmental matrices | DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN); others optimized for environmental samples [7] | All molecular MST methods requiring DNA analysis |

| qPCR/dPCR Reagents | Amplification and detection of host-specific genetic markers | TaqMan Environmental Master Mix; custom primers and probes [8] [7] | Quantitative detection of MST markers |

| Host-Specific Primers/Probes | Target recognition and amplification of host-associated genetic markers | HF183 (human), DogBact (canine), CowM2 (cattle), LeeSeaGull (gull) [4] [8] [7] | Library-independent MST using PCR-based platforms |

| Positive Controls | Verification of assay performance and standard curve generation | gBlocks gene fragments, cloned plasmids, or reference DNA [8] [7] | Quality assurance for molecular assays |

| Microbial Standards | Monitoring extraction efficiency and inhibition | Spike-and-recovery controls; internal amplification standards [4] | Quality control across sample processing |

| Digital PCR Systems | Absolute quantification of genetic markers without standard curves | Bio-Rad QX200/QX600; QIAGEN QIAcuity [8] | Highly accurate quantification resistant to inhibition |

Microbial Source Tracking has evolved from simple phenotypic classifications to sophisticated molecular analyses that can precisely identify contamination sources. The field has progressively moved from library-dependent methods requiring extensive isolate collections to library-independent approaches that detect host-associated genetic markers directly from environmental samples [1] [4]. This evolution has significantly enhanced our ability to protect public health by enabling more accurate risk assessments and targeted remediation efforts.

Current challenges include the need for standardized protocols, understanding marker persistence in the environment, and accounting for geographic variability in marker distributions [4]. Future directions likely involve the development of multiplexed platforms that can simultaneously detect multiple contamination sources, integration with risk assessment models, and the application of machine learning to complex microbial community data [4] [7]. As these technologies continue to mature, MST will play an increasingly vital role in water quality management and public health protection worldwide.

The Critical Need for Source Identification in Risk Assessment

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) has emerged as a critical discipline in environmental water quality and public health protection, addressing the fundamental limitation of traditional fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) monitoring. While conventional FIB methods using Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. can indicate the presence of fecal contamination, they cannot identify its origin—a crucial gap for effective risk assessment and remediation planning [10]. The inability to distinguish between human, agricultural, and wildlife fecal sources has historically hampered the development of targeted interventions, as different sources carry substantially different pathogen profiles and associated human health risks [11].

The growing recognition that fecal pollution represents one of the most significant biological hazards in water systems has driven the development and refinement of MST methodologies [12]. This evolution reflects an understanding that accurate source identification is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental component of quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA), water safety management, and the protection of natural resources [11]. With approximately 75% of assessed stream miles in Oklahoma alone listed as impaired for fecal indicator bacteria, the practical implications for environmental management are substantial [10].

This article examines the critical role of source identification within risk assessment frameworks by comparing the performance characteristics of major MST methodologies. We present experimental data from recent validation studies, detailed methodological protocols, and analytical frameworks that enable researchers to select appropriate markers and methods based on their specific research contexts and performance requirements.

Comparative Performance of Microbial Source Tracking Methods

Method Classification and Fundamental Approaches

MST methods can be broadly categorized into two major types: library-dependent methods (LDMs) that are culture-based and rely on isolate-by-isolate typing of bacteria from various fecal sources and water samples, and library-independent methods (LIMs) that frequently utilize sample-level detection of host-associated genetic markers via PCR or other direct detection approaches [5]. A third category encompasses chemical methods including fecal sterols, optical brighteners, and host mitochondrial DNA analyses [5].

The historical development of MST reflects a transition from phenotypic to genotypic approaches, with early methods including antibiotic resistance analysis (ARA), carbon source utilization patterns, and molecular fingerprinting techniques such as ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) [5] [9]. These have been largely supplemented—though not completely replaced—by more specific molecular methods targeting host-associated microorganisms, particularly members of the order Bacteroidales [10].

Performance Comparison of Major MST Methodologies

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Microbial Source Tracking Methods

| Method Category | Specific Method | Target | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library-Dependent | Antibiotic Resistance Analysis (ARA) | E. coli | 24-27% (Human) | 83-86% (Non-human) | Provides viability information; Low equipment costs | Large library requirements; Geographic variability |

| Library-Dependent | Ribotyping (E. coli, HindIII) | E. coli | 50-85% | 79-92% | High discriminatory power | Labor-intensive; Requires specialized expertise |

| Library-Independent | Bacteroidales PCR (HF183) | Human-associated Bacteroidales | 70-100% | 85-100% | High host specificity; No library requirement | Does not indicate viability; PCR inhibition concerns |

| Library-Independent | E. coli Genetic Markers (CH7) | Chicken-associated E. coli | 67% | 77.9% | Direct targeting of cultured isolates | Limited host range validation |

| Library-Independent | E. coli Genetic Markers (CH9) | Chicken-associated E. coli | 55% | 99.4% | Exceptional specificity for chicken sources | Moderate sensitivity |

| Viral Markers | F+ RNA Coliphage | Human and animal sources | 33-87% | 75-100% | Correlation with viral pathogens; Heat resistance | Variable persistence; Technical complexity |

Performance data compiled from multiple studies demonstrates significant variability between methods [6] [5] [9]. A comprehensive comparison study evaluating nine different MST techniques found that no method perfectly predicted the source material in blind samples, though significant differences in performance capabilities were observed [9].

Host-specific PCR methods generally performed best at differentiating between human and non-human sources, with the HF183 Bacteroidales marker demonstrating particularly robust performance across multiple studies [5] [9]. However, the same evaluation noted that PCR primers were not yet available for effectively differentiating among all non-human sources, highlighting a continuing methodological gap [9].

Viral and F+ coliphage methods reliably identified sewage but were unable to detect fecal contamination from individual humans, limiting their application in non-point source scenarios [9]. Library-based isolate methods demonstrated capability to identify dominant sources in most samples but struggled with false positives, incorrectly identifying fecal sources that were not present in the samples [9]. Among these library-based approaches, genotypic methods generally outperformed phenotypic methods [9].

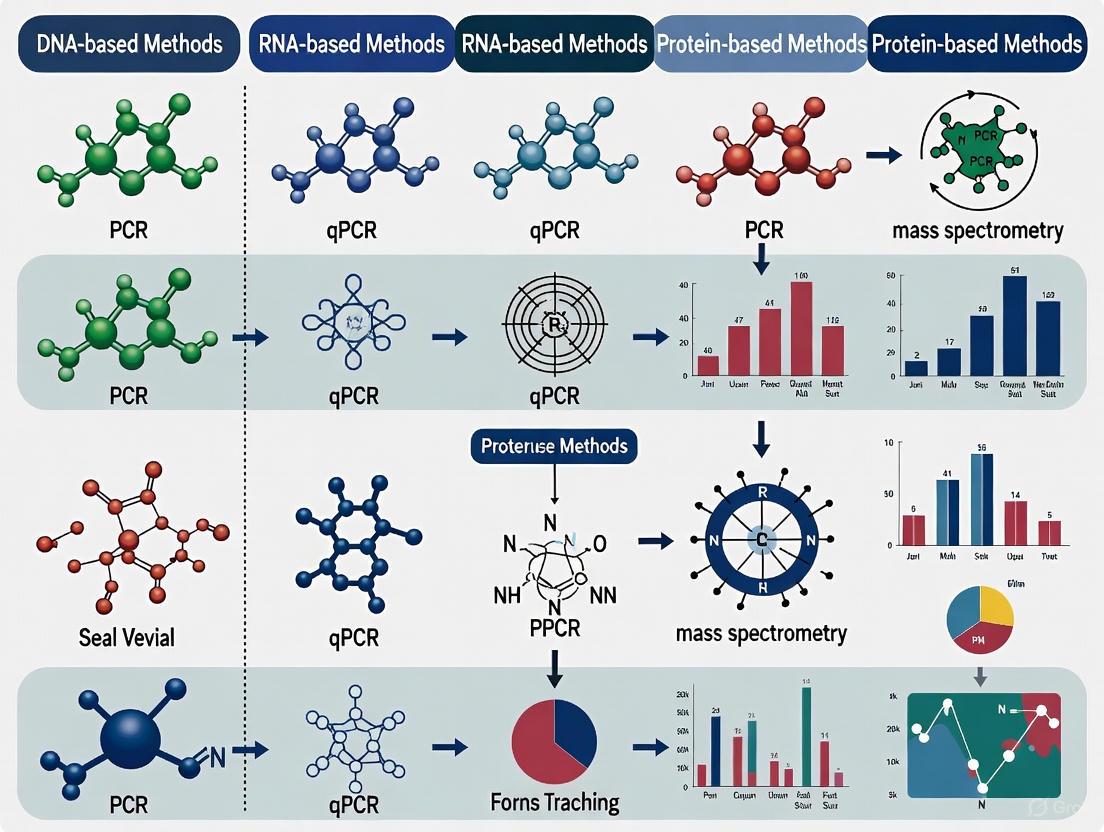

Methodological Workflow Integration

The integration of MST into comprehensive fecal pollution assessment requires understanding how different methodological approaches complement each other. The following workflow diagram illustrates the relationship between traditional fecal indicator monitoring and advanced source tracking approaches:

Experimental Validation of MST Markers

Validation of Host-SpecificE. coliGenetic Markers

A comprehensive 2025 study evaluated nine host-associated E. coli genetic markers for their effectiveness in distinguishing fecal sources from chicken, cow, and pig hosts [6]. The research isolated 563 E. coli strains from these animal sources and assessed them using PCR amplification of previously reported host-associated genetic markers: CH7, CH9, CH12, and CH13 for chicken; CO2 and CO3 for cow; and P1, P3, and P4 for pig sources [6].

The experimental protocol followed this detailed methodology:

Sample Collection and Isolation: Fresh fecal samples were collected from chicken, cow, and pig sources. E. coli strains were isolated using standard culture techniques and confirmed through biochemical testing.

DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification: Genomic DNA was extracted from purified E. coli isolates. PCR reactions were performed using previously reported primer sets specific to each host-associated marker under optimized amplification conditions.

Performance Calculation: Marker performance was evaluated by calculating sensitivity (true positive rate), specificity (true negative rate), and accuracy (overall correct classification rate) using known source samples.

Homology Analysis: The NCBI Microbial Genome database was searched for sequences homologous to the genomic regions of the studied genetic markers. The percentage of host sources and sequence location in the genome (chromosomal or plasmid) was evaluated.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Host-Specific E. coli Genetic Markers

| Target Host | Marker | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | Genomic Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | CH7 | 67.0 | 77.9 | 74.4 | Chromosome & Plasmid |

| Chicken | CH9 | 55.0 | 99.4 | 84.7 | Plasmid |

| Chicken | CH12 | 31.0 | 96.6 | 75.7 | Chromosome |

| Chicken | CH13 | 29.0 | 90.4 | 70.5 | Chromosome & Plasmid |

| Cow | CO2 | 45.8 | 95.4 | 84.5 | Plasmid |

| Cow | CO3 | 33.3 | 96.1 | 82.4 | Chromosome |

| Pig | P1 | 57.1 | 98.2 | 89.7 | Chromosome |

| Pig | P3 | 14.3 | 99.6 | 87.9 | Chromosome & Plasmid |

| Pig | P4 | 42.9 | 99.1 | 89.2 | Chromosome |

The results demonstrated significant variability in marker performance, with CH7 and CH9 emerging as the most effective markers for chicken sources [6]. The homology search revealed that sequences homologous to the CH9 and CO2 markers were located on plasmids, while those for CH12, CO3, P1, and P4 were chromosomal, and CH7, CH13, and P3 were found on both chromosomes and plasmids [6]. This genomic distribution has implications for marker stability and transfer potential between bacteria.

Validation of MST Markers in Ozark Streams

A 2023 field study validated seven MST markers across six Ozark streams with different land use characteristics [10]. The research employed digital PCR (dPCR) to detect human (HF183), bovine (COWM2, COWM3), porcine (Pig-2-Bac), and avian (Av4143) markers alongside traditional culturable assays for E. coli and Enterococcus [10].

The experimental design incorporated:

Site Selection and Sampling: Six streams were selected representing rural agricultural and urban landscapes. Sampling was conducted during the recreational season (May-September) over a two-year period (2019-2020), with five samples collected from each stream within 30-day periods following regulatory standards.

Marker Validation with Known Sources: MST markers were validated using DNA extracted from 56 known-source fecal samples (human, bovine, chicken, goose, pig, and dog) collected from the region.

Water Sample Processing: Two sample bottles were collected at each site: 120mL IDEXX bottles with sodium thiosulfate for culture-based assays, and 500mL sterile polypropylene bottles for MST analysis. Samples were immediately placed on ice and processed upon laboratory arrival.

Digital PCR Analysis: Water samples and known-source fecal samples were analyzed using dPCR for increased quantification accuracy and detection sensitivity compared to conventional PCR.

The study found that rural and agricultural land uses were characterized by bovine sources of bacterial contamination, while human fecal contamination was prominent in developed landscapes [10]. Notably, the research questioned the specificity of culturable Enterococcus assays for FIB water quality standards, finding no relationships between culturable Enterococcus and MST markers except in an urban stream with chronic human fecal pollution issues [10]. In contrast, E. coli levels significantly correlated with dominant MST markers in both rural and urban streams, supporting the continued use of culturable E. coli assays for initial fecal contamination screening [10].

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Enhanced Sensitivity Through High-Volume Ultrafiltration

A 2025 investigation addressed the critical challenge of detecting low-concentration microbial targets in protected water catchments through the application of high-volume ultrafiltration [12]. The research recognized that routine water monitoring programs using low-volume grab sampling with standard filtration face limitations in representative sampling, particularly for protected source waters where wildlife-introduced pathogens exist in low concentrations and uneven distribution [12].

The experimental protocol employed:

Sample Concentration Methods: Comparison of standard grab sampling (500mL-10L) with high-volume EasyElute ultrafiltration system processing 100L samples.

Master Feces Preparation: Creation of standardized fecal material by combining and homogenizing fresh scat samples from multiple representative animal sources (kangaroo, wombat, bird) collected from protected drinking water catchments.

Faecal Dosing Experiments: Controlled addition of master feces mixture to 400L of source water collected from a forested catchment reservoir to evaluate recovery efficiencies.

Integrated Microbial Analysis: Post-concentration analyses combined traditional culture-based quantification of fecal indicator organisms (FIOs) and reference pathogens with 16S rRNA amplicon-based MST.

The results demonstrated that high-volume ultrafiltration enhanced bacterial recovery from source water samples, although turbidity was observed to limit overall efficiency [12]. Comparative analysis showed that amplicon-based MST produced consistent fecal source attribution across both standard and ultrafiltration methods, with greater sensitivity achieved at increasing volumes [12]. This approach is particularly valuable in protected water bodies where FIO and pathogen concentrations typically fall below standard method detection limits.

Methodological Integration Framework

The relationship between sampling methodologies, detection approaches, and source identification capabilities can be visualized through the following experimental framework:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of robust MST studies requires specific research reagents and materials tailored to different methodological approaches. The following table details key solutions and their applications in experimental protocols:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Source Tracking

| Reagent/Material | Category | Specific Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host-Associated Primers (HF183, COWM2, etc.) | Molecular Biology | Amplification of host-specific genetic markers | PCR, dPCR, and qPCR detection of human, bovine, and other fecal sources [10] |

| Digital PCR Master Mix | Molecular Biology | Enables absolute quantification of target DNA without standard curves | High-precision measurement of MST marker concentrations in water samples [10] |

| EasyElute Ultrafiltration Cartridges | Sample Processing | Concentration of microorganisms from large water volumes (up to 100L) | Enhanced detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets in protected waters [12] |

| Selective Culture Media (mEI, mFC, etc.) | Microbiology | Isolation and enumeration of specific FIB groups | Traditional fecal indicator bacteria monitoring (enterococci, E. coli) [10] |

| DNA Extraction Kits (Soil, Water, Fecal) | Molecular Biology | Nucleic acid purification from complex matrices | Preparation of template DNA for PCR-based MST assays [6] [10] |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Chemistry | Neutralization of chlorine in water samples | Preservation of bacterial viability in grab samples for culture-based assays [10] |

The critical need for source identification in risk assessment is fundamentally changing how we approach fecal pollution management in water systems. Performance comparisons clearly demonstrate that while no single MST method is perfect for all applications, strategic selection and combination of methods based on their validated performance characteristics can dramatically improve our ability to identify pollution sources and assess associated risks.

The experimental data presented reveals that method sensitivity varies considerably, with host-specific PCR markers generally outperforming library-dependent methods, particularly for distinguishing human versus non-human sources [9]. The exceptional specificity of certain markers, such as the CH9 chicken-associated E. coli marker at 99.4%, highlights the potential for precise source identification when appropriate validation has been conducted [6]. Meanwhile, methodological advances in sample processing, particularly high-volume ultrafiltration, address the critical challenge of detecting low-abundance targets in protected water systems [12].

The integration of these MST approaches into quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) frameworks represents the most significant advancement in water quality management in recent decades [11]. By moving beyond simple presence/absence measurements of fecal indicators to specific source attribution, environmental managers can now prioritize remediation efforts based on actual human health risk rather than mere indicator concentrations. This paradigm shift enables cost-effective intervention strategies, targeted implementation of best management practices, and ultimately, more sustainable protection of water resources and public health.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on increasing detection sensitivity through advanced concentration techniques, expanding the range of validated host-specific markers, standardizing performance criteria across laboratories, and integrating MST data into predictive models for proactive risk management [11]. As these tools continue to evolve, so too will our capacity to precisely identify and mitigate the most significant fecal pollution threats to water quality and public health.

In the fields of microbial ecology and molecular epidemiology, understanding the genetic mechanisms of host adaptation and utilizing precise tools for microbial fingerprinting are fundamental for tracking pathogens, identifying sources of contamination, and developing targeted therapies. Host adaptation refers to the evolutionary process by which microorganisms genetically specialize to thrive in a particular host environment, a phenomenon driven by specific molecular factors [13]. Microbial fingerprinting encompasses a suite of genotyping techniques that exploit the unique DNA patterns of microorganisms for identification, differentiation, and classification at and below the species level [14] [15]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key methods in this domain, framing them within the context of microbial source tracking (MST) research, which aims to identify the origins of fecal pollution in water and other environments [11].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Host-Specificity vs. Virulence Factors

A critical assumption in host-pathogen interactions is the distinction between general virulence factors and host-specificity factors. While all host-specificity factors influence virulence, not all virulence factors are host-specificity determinants. Basic virulence factors are essential for fundamental infection processes across multiple hosts and do not contribute to incompatibility with non-preferred hosts. In contrast, host-specificity factors modulate virulence in a host-dependent manner, either by conferring avirulence on non-preferred hosts or enhancing virulence on the preferred host [13]. These factors can be effector proteins, which are often small, secreted molecules that modulate plant responses, or they can be secondary metabolites like host-specific toxins [13].

The Strain as an Epidemiological Unit

A foundational assumption in modern microbial genomics is that the strain is the fundamental unit of epidemiological tracking. Phenotypic and pathogenic variation often occurs at the strain level within a single microbial species [16]. For example, Escherichia coli includes commensal, enterohemorrhagic, and probiotic strains, while Staphylococcus aureus encompasses both commensals and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains [16]. This intra-species genomic variation can be substantial, with a "pangenome" far exceeding the "core" genome universal to all strains. Consequently, strain-level resolution is often necessary for accurate source attribution and for understanding the functional consequences of microbial colonization and infection [16].

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Fingerprinting Techniques

Microbial fingerprinting techniques can be broadly categorized into culture-based and molecular methods. The table below compares the key characteristics of several prominent DNA-based fingerprinting methods.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Fingerprinting Techniques for Microbial Strain Typing

| Technique | Principle | Discriminatory Power | Ease of Use | Primary Application | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rep-PCR (e.g., ERIC-, REP-, BOX-PCR) [14] [15] | Amplification of genomic DNA between repetitive elements | Moderate to High [14] | Moderate; requires PCR optimization | Strain differentiation and classification of diverse bacteria [15] | Pattern complexity can vary between primer sets [15] |

| Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) [14] | Restriction digestion of whole genome followed by separation of large DNA fragments | High [14] | Low; technically demanding, slow | High-resolution subtyping of bacterial isolates [14] | Labor-intensive and time-consuming |

| Arbitrarily Primed PCR (AP-PCR) [14] | PCR with random primers to generate anonymous genomic fingerprints | High (with specific primers, e.g., M13) [14] | Moderate; sensitive to reaction conditions | Strain differentiation and variant identification [14] | Reproducibility can be challenging |

| Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) | Sequencing of internal fragments of multiple housekeeping genes | Moderate (species/strain level) | High; highly reproducible | Long-term and global epidemiological studies | Lower discriminatory power than PFGE or rep-PCR |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [16] | High-throughput sequencing of the entire genome | Highest (single nucleotide level) | Variable; computationally intensive | Definitive strain identification and outbreak investigation | High cost and bioinformatics expertise required |

Experimental Protocols for Key Fingerprinting Methods

Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus (ERIC)-PCR

This is a specific and widely used form of rep-PCR.

- Principle: ERIC-PCR uses primers targeting the conserved ERIC sequences dispersed in the bacterial genome to generate a fingerprint of amplified fragments of different sizes, which are separated by gel electrophoresis [14].

- Detailed Workflow:

- DNA Purification: Genomic DNA is extracted from pure bacterial cultures using a commercial kit to ensure purity and integrity [14].

- PCR Reaction Setup: The reaction mixture includes:

- Template DNA (100 ng)

- Primers ERIC1R (5′-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC-3′) and ERIC2 (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAG-AGCG-3′) [14]

- Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs)

- Taq DNA polymerase

- Appropriate buffer

- Thermocycling Conditions: The PCR protocol involves an initial denaturation, followed by cycles of denaturation, annealing (at a primer-specific temperature), and extension.

- Analysis: The PCR products are separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The resulting banding patterns are visualized under UV light after ethidium bromide staining and compared to determine genetic relatedness [14].

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

- Principle: PFGE involves embedding intact bacterial cells in agarose plugs, lysing the cells in situ, and digesting the chromosomal DNA with a rare-cutting restriction enzyme. The resulting large DNA fragments are separated using an apparatus that alternates the direction of the electric field, allowing for the resolution of fragments up to several megabases in size [14].

- Detailed Workflow:

- Preparation of DNA Plugs: Bacterial cells are harvested, washed, and suspended in agarose to form plugs.

- Cell Lysis and DNA Digestion: Plugs are incubated in lysis buffer containing proteinase K to free the DNA. After washing, the DNA within the plugs is digested with a restriction enzyme (e.g., SmaI) [14].

- Electrophoresis: The plugs are loaded into an agarose gel and placed in a PFGE system (e.g., CHEF DRIII). Electrophoresis is run for an extended period (e.g., 30 hours) with pulse times optimized for separation (e.g., 3 to 12 seconds) [14].

- Analysis: The gel is stained with ethidium bromide, and the fingerprint pattern is photographed under UV light. Patterns are analyzed based on the number and size of the bands.

Integration of Fingerprinting Data with Host Adaptation Studies

Linking microbial genotypes to host-specific phenotypes requires a systematic comparative approach. The following workflow outlines the key steps from defining the biological system to validating the molecular factors involved.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Identifying Host-Specificity Factors

Workflow Explanation: The process begins with defining the pathosystem, which involves collecting fungal or bacterial isolates from different hosts or environments and phenotypically characterizing them based on their infection capability and disease symptoms on different host plants [13]. The next step is genotyping, which uses molecular markers like RFLP, rep-PCR, or whole-genome sequencing to establish genetic relationships and identify markers correlated with host-specificity [13]. Comparative -omics analyses then leverage genomics to find genes unique to or variant in host-specific strains, and transcriptomics/proteomics to identify genes/proteins differentially expressed during infection of different hosts [13]. This leads to candidate Gene Prediction, focusing on known classes of host-specificity factors like effectors, genes for secondary metabolite synthesis (e.g., Polyketide Synthases or PKSs), or genes located on accessory chromosomes [13]. Finally, functional validation through gene knockout (to lose host-specific virulence) or heterologous expression (to confer new host-specific traits) confirms the role of the candidate genes [13].

Advanced Data Analysis in Microbial Fingerprinting

The analysis of complex fingerprinting data, such as banding patterns from rep-PCR, can be enhanced using computational tools like artificial neural networks.

Table 2: Comparison of Data Analysis Methods for Genomic Fingerprints

| Analysis Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Analysis [15] | Groups patterns based on pairwise similarity | Well-established, intuitive visualization | Computationally intensive for large libraries; requires database search for each new sample |

| Backpropagation Neural Network (BPN) [15] | A connectionist network trained to identify complex patterns | Computationally efficient after training; can identify patterns without pairwise database comparisons | Requires upfront, computation-intensive training; needs a well-characterized training set |

Diagram Title: Neural Network Analysis of DNA Fingerprints

Diagram Explanation: The process of using a Backpropagation Neural Network (BPN) for bacterial identification starts with the input of rep-PCR genomic fingerprints [15]. These raw fingerprint patterns are digitized and normalized during data preprocessing. The preprocessed data is then fed into the BPN, which consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [15]. During the critical training phase, the network is presented with known fingerprint patterns and adjusts its internal connection weights to learn the association between specific patterns and bacterial identities [15]. Once trained, the BPN can rapidly identify an unknown bacterial sample by processing its fingerprint through these learned internal connections, without needing to compare it to every entry in a reference database [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Microbial Fingerprinting and Host Adaptation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Selective & Differential Media [17] | Allows selective growth and preliminary identification of target microorganisms from complex samples. | Isolating Listeria monocytogenes or Salmonella from food or environmental samples [17]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits [14] | Provides a standardized, reliable method for purifying high-quality genomic DNA from microbial cultures. | Extracting template DNA for downstream applications like ERIC-PCR or PFGE [14]. |

| Repetitive Sequence Primers (ERIC, REP, BOX) [14] [15] | Serve as primers in PCR to generate strain-specific genomic fingerprints. | Differentiating between strains of Xanthomonas or Bartonella henselae via rep-PCR [14] [15]. |

| Rare-Cutting Restriction Enzymes (e.g., SmaI) [14] | Digest bacterial chromosomal DNA into a limited number of large fragments for PFGE analysis. | Macro-restriction digestion of DNA embedded in agarose plugs for high-resolution subtyping [14]. |

| Taq Polymerase & dNTPs [14] | Essential components for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), enabling targeted DNA amplification. | Amplifying DNA fragments in ERIC-PCR, AP-PCR, and other PCR-based fingerprinting methods [14]. |

| Reference Genomic DNA | Serves as a positive control and benchmark for molecular assays and sequencing-based comparisons. | Used as a control strain (e.g., B. henselae Houston-1) in comparative fingerprinting studies [14]. |

| Scoparinol | Scoparinol, MF:C27H38O4, MW:426.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Andropanolide | Andropanolide, MF:C20H30O5, MW:350.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For decades, the assessment of water quality and the associated public health risks has relied predominantly on the use of fecal indicator bacteria (FIB), such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) and enterococci. These organisms serve as proxies for the potential presence of fecal contamination and, by extension, pathogenic microorganisms. However, the FIB paradigm is fundamentally imperfect. A primary shortcoming is that the presence of FIB does not always correlate with the occurrence of pathogens, particularly viruses or protozoa [18]. Furthermore, elevated concentrations of FIB provide no indication of the source of fecal contamination (human, ruminant, gull, dog, etc.), which critically hinders effective remediation efforts [18]. The inability to accurately identify the contamination source can also lead to inaccurate public health decisions, as different sources pose varying degrees of risk, with human sewage contamination generally considered the most significant threat to human health [18]. This recognition has driven a conceptual shift in environmental microbiology—from merely quantifying indicator organisms to attributing contamination to specific sources.

The Rise of Microbial Source Tracking (MST)

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) represents a suite of advanced methodologies designed to discriminate between human and animal sources of fecal pollution. This approach typically utilizes host-associated molecular markers based on the phylogenetic analysis of microbial communities, such as Bacteroides and related genera, which are abundant in the gut and often exhibit host specificity [18].

Key Host-Associated MST Markers

The application of MST involves detecting these host-specific markers through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or quantitative PCR (qPCR). The table below summarizes the key MST markers used to identify various contamination sources.

Table 1: Key Microbial Source Tracking (MST) Markers and Their Targets

| Source Target | Representative Markers | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|

| General Fecal Contamination | Bacteroidales spp. | Endpoint PCR, qPCR |

| Human | Human-associated Bacteroides markers (e.g., HF183) | qPCR |

| Ruminant/Cow | Ruminant-associated markers (e.g., BacR) | qPCR |

| Gull | Gull-associated markers | qPCR |

| Dog | Dog-associated markers | qPCR |

The effectiveness of these markers was demonstrated in a comprehensive study of the Humber River watershed, where human and gull fecal sources were detected at all sampled sites. The concentration of the human fecal marker was notably higher in stormwater outfalls, indicating significant raw sewage contamination from compromised infrastructure [18]. Furthermore, the performance of specific FIB can vary by environment; for instance, E. coli and Clostridium perfringens have been identified as providing a reliable "consensus picture" of faecal pollution in tropical waters, and ruminant markers (BacR) were detected in over three-fourths of the sites in a study conducted in Ethiopia [19].

The Advent of Chemical Source Tracking (CST)

Parallel to the development of MST, Chemical Source Tracking (CST) has emerged as a complementary approach. CST utilizes chemical markers that are specific to human wastewater, offering an independent line of evidence for sewage contamination.

Key Chemical Markers for Wastewater

These markers include anthropogenic compounds that are consumed, metabolized, and subsequently excreted by humans. Their presence in environmental waters is a direct indicator of human sewage impact. The following table lists the primary CST markers and their origins.

Table 2: Key Chemical Source Tracking (CST) Markers for Human Wastewater

| Chemical Marker | Category | Origin/Use |

|---|---|---|

| Caffeine | Stimulant | Beverages, Food |

| Carbamazepine | Pharmaceutical | Antiepileptic Drug |

| Codeine | Pharmaceutical | Analgesic Drug |

| Cotinine | Metabolite | Nicotine Metabolite |

| Acetaminophen | Pharmaceutical | Analgesic Drug |

| Acesulfame | Artificial Sweetener | Food & Beverage Additive |

In the Humber River study, the co-detection of high concentrations of caffeine, acetaminophen, acesulfame, E. coli, and the human MST marker provided multiple, converging lines of evidence for raw sewage contamination, particularly at several stormwater outfalls and the Black Creek tributary [18].

Comparative Analysis: MST vs. CST in Practice

A direct comparison of MST and CST methodologies reveals the relative strengths and applications of each approach, underscoring why their combined use is most powerful.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Microbial and Chemical Source Tracking Methods

| Parameter | Microbial Source Tracking (MST) | Chemical Source Tracking (CST) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | Host-associated microorganisms | Anthropogenic chemical compounds |

| Detection Method | PCR, qPCR | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) |

| Source Specificity | High (can distinguish human, ruminant, gull, dog) | High for human wastewater (specific chemicals) |

| Persistence in Environment | Varies; some markers can persist for weeks | Varies; some (e.g., acesulfame) are highly persistent |

| Sensitivity | High (detects few copies of DNA) | High (detects trace concentrations) |

| Quantification | Yes (via qPCR, copies/100 ml) | Yes (via mass spectrometry, ng/liter) |

| Limitations | DNA can be degraded; may not indicate viable pathogens | Affected by human consumption patterns & wastewater treatment |

The quantitative data from the Humber River study highlights the utility of both methods. For example, one site showed a human MST marker concentration of 7.65 log10 CN/100 ml, coupled with caffeine levels at 34,800 ng/liter and acetaminophen at 5,120 ng/liter [18]. This strong correlation provides robust, multi-faceted evidence that is more reliable than relying on a single method.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, this section outlines the standard protocols for MST and CST analyses as employed in the cited research.

Protocol for Microbial Source Tracking (qPCR)

1. Sample Collection:

- Collect a 500-ml water sample in an autoclaved polypropylene bottle.

- Transport on ice to the laboratory and process within 6 hours of collection [18].

2. Filtration and DNA Extraction:

- Filter an appropriate volume of water through a 0.22 μm or 0.45 μm membrane filter.

- Extract genomic DNA from the material collected on the filter using a commercial DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerWater Kit from QIAGEN).

3. Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Prepare qPCR reactions containing a DNA template, forward and reverse primers specific to the host-associated marker (e.g., human HF183, gull, ruminant BacR), a fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan), and a master mix.

- Run samples in triplicate on a real-time PCR instrument alongside a standard curve of known copy number to enable absolute quantification.

- Calculate the concentration of the marker in the original water sample, expressed as log10 copy numbers (CN) per 100 milliliters [18].

Protocol for Chemical Source Tracking (LC-MS/MS)

1. Sample Collection:

- Collect a 100-ml water sample in an amber glass bottle to protect from light.

- Preserve with a biocide (e.g, sodium azide) if immediate analysis is not possible. Transport on ice and store at 4°C prior to analysis [18].

2. Solid Phase Extraction (SPE):

- Acidify the water sample to pH ~2.

- Pass the sample through a pre-conditioned SPE cartridge (e.g., Oasis HLB from Waters Corporation) to concentrate the chemical analytes.

- Elute the analytes from the cartridge with a small volume of organic solvent (e.g., methanol).

3. Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS):

- Inject the extracted sample into the LC-MS/MS system.

- Separate the compounds using a reverse-phase C18 column with a gradient of water and methanol/acetonitrile containing a volatile buffer.

- Detect and quantify the target compounds using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode by comparing against a calibrated standard curve. Report concentrations in nanograms per liter (ng/liter) [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of MST and CST requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Source Tracking Studies

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Supplier / Product |

|---|---|---|

| Autoclaved Polypropylene Bottles | Sterile container for water sample collection for microbiological and DNA analysis. | VWR, Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Amber Glass Bottles | Sample container for chemical analysis; protects light-sensitive analytes. | VWR, Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Membrane Filters (0.22/0.45 μm) | Concentration of microorganisms from water samples for DNA extraction. | EMD Millipore, Pall Corporation |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from filtered biomass. | QIAGEN DNeasy PowerWater Kit |

| qPCR Primers & Probes | Host-specific oligonucleotides for detection and quantification of MST markers. | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Concentration and clean-up of chemical markers from water samples. | Waters Corporation Oasis HLB |

| Chemical Analytical Standards | Pure reference standards for CST markers (e.g., caffeine, carbamazepine) for instrument calibration. | Sigma-Aldrich, Cerilliant |

| Ac-RLR-AMC | Ac-RLR-AMC, MF:C30H46N10O6, MW:642.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganosporeric acid A | Ganosporeric acid A, MF:C30H38O8, MW:526.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Conceptual Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The integrated approach to source attribution involves a logical sequence from field sampling to data interpretation. The diagram below visualizes this conceptual workflow and the relationship between its components.

Diagram 1: Integrated Source Attribution Workflow.

The shift from simple indicator monitoring to sophisticated source attribution also represents a fundamental change in the analytical "pathway" for environmental monitoring. The following diagram contrasts the traditional and modern paradigms.

Diagram 2: Paradigm Shift from Indicator Monitoring to Source Attribution.

The conceptual shift from relying solely on indicator organisms to employing sophisticated source attribution techniques marks a maturation of environmental microbiology. While FIB like E. coli remain useful as initial screening tools, they are insufficient for guiding targeted and cost-effective remediation. The integration of Microbial Source Tracking and Chemical Source Tracking provides a powerful, multi-evidence framework that not only confirms fecal pollution but also reliably identifies its origin—be it human, agricultural, or wildlife. This paradigm shift, as evidenced by studies in diverse environments from Toronto to Ethiopia, enables stakeholders to move from broad, often ineffective cleanup efforts to precise interventions, such as repairing specific sewage cross-connections, thereby offering a more robust strategy for protecting ecosystem and human health.

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) comprises a suite of methodological tools designed to identify, and in many cases quantify, the dominant sources of fecal contamination in environmental waters [11] [5]. Accurate identification of pollution sources—whether human, agricultural, or wildlife—is critical for effective water quality management, public health risk assessment (QMRA), and remediation strategies [12] [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the major protocol components in MST, objectively evaluating the performance of different source identifiers and detection methods based on experimental data, and detailing the essential reagents and workflows that underpin this field.

Core Components of Microbial Source Tracking

MST methodologies are fundamentally built upon three interconnected pillars: the source identifiers (host-specific markers), the technological platforms for detecting these markers, and the analytical approaches for data interpretation and source apportionment.

Source Identifiers (Markers)

Source identifiers, or markers, are biological or chemical signals strongly associated with the gut microbiota of a specific host. The transition from library-dependent to library-independent methods represents a major evolution in the field [5] [20].

Table 1: Categories and Examples of Microbial Source Tracking Markers

| Marker Category | Description | Example Targets | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library-Dependent Methods (LDM) | Rely on culturing isolates (e.g., E. coli, enterococci) from water and comparing them to a library of isolates from known sources [5]. | Phenotypic (Antibiotic Resistance Analysis, Carbon Source Utilization) or Genotypic (Ribotyping, REP-PCR, PFGE) profiles of bacteria [9] [5]. | Labor-intensive; performance varies significantly with library size and representativeness; prone to false positives [9] [5]. |

| Library-Independent Methods (LIM) | Direct, culture-independent detection of host-associated genetic markers from a sample [5] [20]. | Host-specific bacterial (e.g., Bacteroidales 16S rRNA markers HF183 [human], BacR [ruminant]), viral (e.g., human adenovirus), or mitochondrial DNA markers [12] [21] [22]. | Higher specificity and speed; no need for isolate libraries;å·²æˆä¸ºä¸»æµæ–¹æ³• [5] [20]. |

The performance of these markers is quantified by their sensitivity (ability to correctly identify a true source) and specificity (ability to avoid false positives from non-target sources) [5]. Experimental data from comparative studies provide critical insights for method selection.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected MST Markers from Experimental Studies

| Marker / Method | Target Host | Sensitivity (n) | Specificity (n) | Experimental Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidales PCR (HF183) | Human | 0.70 - 1.00 (10-41) [5] | 0.93 - 1.00 (7-75) [5] | One of the most widely used human-associated markers; performance is high in wastewater [5]. |

| Bacteroidales PCR (BacR) | Ruminant | 1.00 (19-31) [5] | 0.70 - 1.00 (28-40) [5] | Target of isothermal HDA-strip test; demonstrates high source-sensitivity [22]. |

| Bacteroidales PCR (CF128) | Ruminants & Pseudoruminants | 0.97 - 1.00 (20-31) [5] | 1.00 (20-28) [5] | Shows excellent specificity in experimental testing with individual feces [5]. |

| F+ RNA Coliphage Genotyping | Human | 0.33 - 0.87 (3-403) [5] | 0.75 - 0.91 (4-2495) [5] | Broad performance range; reliably identifies sewage but may not detect individual humans [9] [5]. |

| Host-specific PCR | Human vs. Non-human | High accuracy [9] | High accuracy [9] | Performed best in a blind study for human/non-human differentiation, but primers for non-human sources were limited [9]. |

| Ribotyping (Library-Dependent) | Human | 0.06 - 1.00 (17-84) [5] | 0.00 - 0.92 (1-317) [5] | Performance is highly variable and context-dependent; can struggle with false positives and blind samples [9] [5]. |

Detection Methods and Technological Platforms

The technological platforms for detecting MST markers have expanded from traditional culture methods to include a suite of molecular and emerging techniques.

Sample Concentration and Processing

For low-concentration water samples, especially from protected catchments, an initial concentration step is often critical. High-volume ultrafiltration has been demonstrated to enhance the recovery of FIOs, reference pathogens, and genetic markers compared to standard low-volume grab sampling, thereby improving the sensitivity of downstream MST assays [12]. However, the efficiency of this concentration can be limited by high turbidity [12]. The experimental protocol typically involves processing large volumes of water (e.g., 100 L) through a portable ultrafiltration system, with the retentate then analyzed or further processed for DNA extraction [12].

Molecular Detection Platforms

- Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR): This is the current gold-standard molecular method for quantifying host-associated genetic markers in environmental samples [12] [20]. It provides sensitive, quantitative data but requires specialized, costly thermocyclers and trained personnel, which can limit its use in some settings [22].

- Isothermal Amplification Methods (e.g., HDA, LAMP): These techniques amplify nucleic acids at a constant temperature, eliminating the need for expensive thermal cyclers [22] [20]. For instance, a developed helicase-dependent amplification (HDA) assay for the ruminant BacR marker runs on a standard heating block and is paired with a lateral-flow strip for visual detection [22]. The entire HDA-strip assay is completed in two hours and achieved comparable source-sensitivity and specificity to the qPCR reference method in experimental validation, though it yields qualitative (presence/absence) results [22].

- High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS): Metagenomics and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing (16S AmpSeq) represent powerful, library-independent approaches for MST [12] [11] [20]. These methods can provide a comprehensive profile of the fecal microbiome without prior selection of specific markers, allowing for the discovery of new source identifiers and the application of machine learning models for source apportionment [11].

Analytical Approaches

The final component involves analyzing the generated data to attribute fecal pollution to its sources. This can range from simple binary presence/absence of a host-specific marker to complex source apportionment models that estimate the fractional contribution of different hosts to the overall fecal pollution [11] [9]. The integration of MST data with Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA) is a growing field, enabling managers to link specific pollution sources to human health risks [11]. The rise of HTS and bioinformatics has further enabled the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze complex microbial community data for source tracking [11].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of MST protocols relies on a suite of specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MST Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function in MST Protocol | Experimental Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| EasyElute Ultrafiltration System | High-volume concentration of microbes from water samples for enhanced detection sensitivity. | Used to process 100L source water samples, improving recovery of FIOs and MST markers in low-load conditions [12]. |

| Master Faeces (MF) Sample | A standardized, homogenized composite fecal sample from multiple animals used for method validation and recovery experiments. | Created from >5 animals per source type; used as a positive control and for "dosing" experiments to test method accuracy [12]. |

| Selective Culture Media | For cultivation and enumeration of Faecal Indicator Organisms (FIOs) like E. coli and enterococci. | Used in conjunction with molecular methods for integrated microbial risk assessment [12]. |

| Host-Specific Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to bind and amplify (qPCR) or detect (strip test) a unique genetic sequence of a host-associated marker. | e.g., BacR primers for ruminants [22]; HF183 for humans [5]. Critical for assay specificity. |

| Helicase-Dependent Amplification (HDA) Kit | Isothermal enzymatic system for amplifying DNA at a constant temperature (~65°C). | Core component of the simplified BacR detection assay, replacing the need for a PCR machine [22]. |

| Nucleic Acid Lateral-Flow Strip | A paper-based device for visual, colorimetric detection of amplified DNA via hybridization. | Used to detect BacR HDA amplicons; contains a test line and a control line for result validation [22]. |

| Gold Nanoparticle-Labelled Detector Probe | Conjugated probe that hybridizes to amplified DNA, forming a visible red line on the test strip when captured. | Key reagent in the HDA-strip test format, enabling visual readout without instrumentation [22]. |

The field of MST offers a diverse "toolbox" of methods, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The choice of protocol components—source identifier, detection platform, and analytical approach—must be guided by the specific research or management question, the required performance characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, quantitative output), and available resources. The trend is moving decisively towards library-independent, molecular methods, particularly qPCR and, increasingly, isothermal assays for field applications and sequencing for discovery and high-resolution source profiling. The experimental data and comparative performance metrics outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers and professionals to make informed decisions in selecting and implementing MST methodologies for protecting water quality and public health.

MST Methodologies: From Library-Dependent to Molecular Approaches

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) is a critical scientific discipline focused on identifying the origin of fecal contamination in environmental waters. Understanding whether contamination stems from human, livestock, wildlife, or avian sources is essential for accurate health risk assessment and effective remediation strategies [23]. Library-Dependent Methods (LD-MST) represent a foundational approach within this field, relying on the creation of reference libraries containing phenotypic or genotypic characteristics of bacteria from known sources. These libraries serve as comparative databases for classifying environmental isolates of fecal indicator bacteria, most commonly Escherichia coli (E. coli) and enterococci.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three established LD-MST methodologies: Ribotyping, Antibiotic Resistance Analysis (ARA), and Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE). We will objectively analyze their technical principles, performance metrics based on experimental data, and suitability for different research scenarios, framed within the broader context of MST method evolution toward molecular, library-independent techniques.

Principles and Experimental Protocols

Ribotyping

Principle: Ribotyping is a genetic fingerprinting technique that targets the polymorphisms in the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene operon. It involves digesting bacterial genomic DNA with restriction enzymes, separating the fragments via gel electrophoresis, and then hybridizing them with a labeled probe specific to the highly conserved rRNA genes [24] [25]. The resulting banding pattern, or ribotype, is characteristic of a strain and can be compared against a reference library.

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Purify high-quality genomic DNA from pure cultures of fecal indicator bacteria (e.g., E. coli) isolated from water samples and known source materials.

- Restriction Digestion: Digest the DNA (≈2-5 µg) with a frequent-cutting restriction enzyme (e.g., HindIII, PvuII, or BglI). The choice of enzyme can impact the resolution [26] [24].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Separate the digested DNA fragments by size using a standard agarose gel.

- Southern Blotting: Transfer the DNA fragments from the gel onto a nitrocellulose or nylon membrane.

- Hybridization: Probe the membrane with a labeled (e.g., digoxigenin or chemiluminescent) DNA fragment derived from the 16S or 23S rRNA gene.

- Detection: Visualize the hybridized restriction fragments containing rRNA genes to generate the ribotype pattern for analysis [25].

Antibiotic Resistance Analysis (ARA)

Principle: ARA is a phenotypic method based on the premise that enteric bacteria from different host species develop distinct antibiotic resistance profiles due to varying levels of exposure to antibiotics. The resistance patterns of environmental isolates are compared to a library of patterns from bacteria of known origin [23].

Detailed Protocol:

- Bacterial Isolation: Isolate fecal indicator bacteria (typically E. coli) from environmental water samples and known source samples on selective media.

- Pure Culture Preparation: Inoculate individual bacterial colonies into broth and incubate.

- Antibiotic Profiling: Using a replica-plating technique or a microtiter plate system, test each bacterial isolate against a panel of multiple antibiotics at different concentrations. A common panel may include ampicillin, tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole, and streptomycin.

- Data Collection: Record growth (resistance) or no growth (susceptibility) for each isolate against each antibiotic.

- Pattern Analysis: The unique resistance profile for each isolate serves as its fingerprint for library matching.

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

Principle: PFGE is a high-resolution genomic fingerprinting method that involves digesting bacterial chromosomal DNA with rare-cutting restriction enzymes to generate a small number of large DNA fragments (10-800 kb). These large fragments are separated by size using an electrophoresis apparatus that periodically changes the direction of the electric field, allowing for clear resolution of the fragments [26] [25].

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Preparation in Situ: Embed bacterial cells in an agarose plug to protect the large, fragile chromosomal DNA from shearing.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse the cells within the plug using a detergent-enzyme solution (e.g., proteinase K).

- Restriction Digestion: Digest the DNA within the plug with a rare-cutting restriction enzyme (e.g., CpoI, SmaI, or XbaI).

- Pulsed-Field Electrophoresis: Load the plug into an agarose gel and run in a specialized PFGE system. Key parameters include pulse time (which increases during the run), voltage, and run duration (typically 18-24 hours).

- Staining and Visualization: Stain the gel with ethidium bromide or a safer fluorescent alternative and visualize under UV light to obtain the fingerprint pattern [26] [24].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the general process of applying these three LD-MST methods to identify fecal pollution sources.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of Ribotyping, ARA, and PFGE based on published experimental data and reviews.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of LD-MST Methods

| Feature | Ribotyping | Antibiotic Resistance Analysis (ARA) | Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typing Basis | Genotypic (rRNA gene polymorphisms) | Phenotypic (resistance profile) | Genotypic (whole-genome macro-restriction) |

| Discriminatory Power | Moderate to High | Moderate | Very High |

| Key Performance Data | Differentiated 4 ribotypes in V. cholerae O139 [26]. Index of Discrimination (ID): 0.83 for Streptococcus spp. [24]. | Limited specific data found in search results; generally considered less discriminatory than genotypic methods. | Differentiated 5-11 subtypes in V. cholerae O139 [26]. ID: 0.97 for Streptococcus spp. [24]. |

| Reproducibility | High, especially with standardized protocols and capillary electrophoresis [25]. | Moderate; can be influenced by growth conditions and antibiotic concentration. | High, though inter-laboratory comparison requires strict standardization [25]. |

| Library Requirement | Large, robust library required for confident source assignment. | Large library required; profile stability over time is a concern. | Large library required. |

| Throughput | Moderate | High | Low (technically demanding and slow) |

| Cost | Moderate | Low | High |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate (requires Southern blotting or capillary systems) | Low | High (requires specialized PFGE equipment) |

| Primary Applications | Strain differentiation, outbreak investigation, epidemiological studies [25]. | Preliminary source screening, studies in areas with high antibiotic use. | High-resolution outbreak investigation, strain phylogeny studies [26] [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of LD-MST methods requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LD-MST

| Item | Function in LD-MST | Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | Cuts DNA at specific sequences to generate fragments for fingerprinting. | HindIII, PvuII for Ribotyping [24]; SmaI, CpoI for PFGE [26] [25]. |

| rRNA Gene Probe | Hybridizes to conserved rRNA genes on Southern blots to generate ribotype patterns. | Labeled (e.g., digoxigenin) 16S/23S rDNA probe is critical for Ribotyping [25]. |

| Agarose | Matrix for separating DNA fragments by size via gel electrophoresis. | Standard agarose for Ribotyping/ARA; High-strength agarose for PFGE plugs and gels [26]. |

| Antibiotic Panels | To determine the unique resistance profile of bacterial isolates. | A suite of antibiotics at various concentrations is essential for ARA [23]. |

| Proteinase K | Degrades proteins for DNA purification and inactivates nucleases during cell lysis. | Used during the in-gel lysis step of PFGE protocol to extract intact chromosomal DNA [25]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Standard for determining the size of separated DNA fragments. | Lambda ladder or yeast chromosomal markers are used for size calibration in PFGE [26]. |

| Pulsed-Field Electrophoresis System | Specialized apparatus that alternates electric field direction to separate large DNA fragments. | Essential hardware for performing PFGE; different systems exist (e.g., CHEF, FIGE) [25]. |

| Peucedanocoumarin I | Peucedanocoumarin I, MF:C21H24O7, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Amarasterone A | Amarasterone A, MF:C29H48O7, MW:508.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis of Ribotyping, ARA, and PFGE reveals a clear trade-off between resolution, throughput, and technical demand. PFGE consistently demonstrates superior discriminatory power, as evidenced by its high Index of Discrimination (0.97) and ability to subtype closely related strains in outbreak settings [26] [24]. Ribotyping offers a robust, reproducible, and moderately high-resolution alternative, particularly valuable in standardized surveillance programs, such as the European C. difficile surveillance network [25]. ARA, while lower in cost and technical barrier, provides a phenotypic perspective but is generally considered to have lower discriminatory power and stability compared to genotypic methods.

The broader trend in MST research is a decisive shift toward library-independent, molecular methods (e.g., PCR-based detection of host-specific genetic markers) and high-throughput genomic sequencing [23] [21]. These methods provide faster, more specific results without the need for building and maintaining extensive isolate libraries. Nevertheless, the detailed strain-level differentiation provided by LD-MST methods like PFGE and Ribotyping remains invaluable for forensic-level source tracking, investigating transmission pathways, and understanding the epidemiology of specific bacterial clones. Therefore, while the application of these LD-MST methods may become more specialized, their role in resolving complex contamination scenarios and advancing fundamental microbial ecology knowledge remains secure.

Library-independent methods (LIMs) for microbial source tracking (MST) represent a paradigm shift in how researchers identify the origins of fecal contamination in environmental waters. Unlike older, library-dependent approaches that require building local databases of microbial profiles, LIMs use direct PCR-based detection of host-specific genetic markers, offering a faster, more scalable, and highly specific solution for environmental surveillance. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these methods, grounded in experimental data and protocols, for research scientists and professionals in drug development and environmental health.

Core Principles and Technological Basis of LIMs

Library-independent methods bypass the need for constructing large, localized fingerprint libraries of fecal microbes. Instead, they are founded on the principle of detecting host-associated genetic markers—unique DNA sequences from microorganisms that are strongly and specifically associated with the gut microbiome of a particular host, such as humans, bovines, or poultry [27]. The most common targets are 16S rRNA genes from obligate anaerobic bacteria of the order Bacteroidales [28] [27]. These bacteria constitute a significant portion of the gut microbiota and have co-evolved with their hosts, leading to the development of host-specific phylogenetic clusters that can be targeted by PCR assays [28].