Navigating the High-Dimensional Jungle: A Researcher's Guide to Microbiome Data Analysis

The analysis of microbiome data presents a unique set of computational and statistical challenges due to its high dimensionality, sparsity, compositionality, and complex dependencies.

Navigating the High-Dimensional Jungle: A Researcher's Guide to Microbiome Data Analysis

Abstract

The analysis of microbiome data presents a unique set of computational and statistical challenges due to its high dimensionality, sparsity, compositionality, and complex dependencies. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing these challenges effectively. We cover the foundational characteristics of microbiome data, explore a suite of methodological approaches from traditional statistics to advanced machine learning, outline best practices for troubleshooting and optimization, and provide a framework for the rigorous validation and comparison of analytical methods. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to derive robust, reproducible, and biologically meaningful insights from complex microbiome datasets, thereby accelerating translational applications in biomedicine.

Understanding the Microbiome Data Landscape: Core Challenges and Initial Exploration

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What does the 'p >> n' problem mean in the context of microbiome research? The 'p >> n' problem, also known as the "large P, small N" problem or the curse of dimensionality, describes a scenario where the number of variables (p, e.g., microbial taxa or genes) is much larger than the number of samples or observations (n) [1] [2] [3]. For example, a study might have genomic data on thousands of bacterial taxa (p) collected from only dozens of patients (n) [1] [2].

2. What are the specific consequences of high dimensionality for my analysis? High-dimensional microbiome data exhibits several characteristics that violate the assumptions of classical statistical methods developed for smaller datasets [1] [3]:

- Sparsity and Distance distortion: Data points become distant from each other and tend to fall on the edges of the distribution, making reliable inference difficult [1].

- Overfitting: Predictive models can achieve deceptively high accuracy by fitting to noise rather than to true biological signals [1] [2].

- Compositionality: The data represents relative abundances (proportions) rather than absolute counts, meaning an increase in one taxon necessarily leads to a decrease in others [3].

- Zero-inflation: Many microbial features are rare and absent from most samples, resulting in datasets with a large number of zero values [3].

3. My model performs perfectly on my dataset. Could this be a problem? Yes, this is a classic symptom of overfitting in high-dimensional settings [1]. A model that appears to have near-perfect accuracy may be memorizing the noise in your specific dataset rather than learning generalizable patterns. This model will likely perform poorly on a new, independent dataset. It is crucial to use validation cohorts and penalized regression methods designed to avoid overfitting [2].

4. How should I approach the statistical analysis of my high-dimensional microbiome data? Given the exploratory nature of many high-throughput microbiome studies, your analysis strategy should prioritize interpretability and hypothesis generation [1]. Key approaches include:

- Data Reduction: Focus on biologically meaningful subsets of variables (e.g., specific metabolic pathways) rather than analyzing all variables at once [1].

- Specialized Methods: Employ statistical models designed for high-dimensional data, such as regularized regression ensembles (e.g., stability selection, Bayesian model averaging) [2] or methods that account for compositionality and zero-inflation [4] [3].

- Validation: Treat findings from initial analyses as hypotheses to be confirmed in follow-up, specifically designed experiments [1].

5. What are common confounding factors I need to control for in my study design? The microbiome is influenced by many factors. To avoid spurious associations, carefully document and control for confounders such as [5]:

- Demographics: Age, sex, and geography.

- Lifestyle: Diet, antibiotic use, and pet ownership.

- Technical Factors: DNA extraction kit batches, sequencing runs, and sample storage conditions [6] [5].

- Animal Studies: "Cage effects," where co-housed animals share similar microbiota, must be accounted for by housing multiple cages per study group [5].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model is 100% accurate on training data but fails on new data. | Severe overfitting; the model is fitting to noise. | Use penalized/regularized regression (e.g., elastic net, spike-and-slab BMA) [2] and always validate results on a hold-out or independent dataset. |

| Statistical results are unstable; different subsets of data yield different significant taxa. | Instability due to high dimensionality and multicollinearity. | Implement ensemble methods like Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) or stability selection that aggregate findings across many models [2]. |

| Unable to distinguish true biological signal from background. | High technical noise and/or low microbial biomass in samples. | Incorporate positive and negative controls in your laboratory workflow. For low-biomass samples, analyze controls to identify and subtract contaminating sequences [5]. |

| Strong batch effects are obscuring biological differences. | Unaccounted technical variation from different processing batches. | Record batch information (e.g., DNA extraction kit lot, sequencing run) and include it as a covariate in statistical models or use batch-correction algorithms [5] [7]. |

| Findings are biologically uninterpretable. | Using "black box" algorithms or analyzing too many variables at once. | Conduct focused analyses on subsets of variables selected based on biological knowledge (e.g., specific pathways like methionine degradation) [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Managing High-Dimensional Data

Protocol 1: Focused, Biologically-Informed Subset Analysis This protocol avoids the pitfalls of analyzing all variables simultaneously by focusing on pre-defined, interpretable subsets [1].

- Define a Biological Question: Start with a specific hypothesis (e.g., "Is the methionine degradation pathway in the gut microbiome associated with insulin resistance?") [1].

- Select Variable Subset: Instead of using all thousands of microbial genes or taxa, select a small subset relevant to your hypothesis (e.g., the 4 genes in the methionine degradation pathway) [1].

- Apply Statistical Model: Use a regression model or other multivariate method (e.g., RLQ analysis) appropriate for the data type and your focused variable set [1].

- Interpret and Validate: Interpret the results in the context of the specific biology. Consider any significant findings as hypotheses to be tested in a future, confirmatory study [1].

Protocol 2: Ensemble-Based Regression for Robust Feature Selection This protocol uses ensemble methods to stabilize model selection and identify robust microbial signatures from high-dimensional data [2].

- Data Preprocessing: Log-transform relative abundances of microbial genera to ensure variables have a similar dynamic range [2].

- Model Training:

- Frequentist Approach (Stability Selection): Use bootstrap sampling of your data and fit a penalized regression model (e.g., elastic net) to each sample. Identify variables that are consistently selected across the bootstrap runs [2].

- Bayesian Approach (Spike-and-Slab BMA): Use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms to explore a large space of possible models. Average the results, weighting models by their posterior probability [2].

- Evaluate Performance: Assess the model's performance using metrics like predictive accuracy on held-out data and the stability of the selected features [2]. Studies suggest that Bayesian ensembles exploring larger model spaces often yield stronger performance with lower variability [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Target conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene to amplify variable regions (e.g., V3-V4) for bacterial identification and profiling [6]. |

| DADA2 / QIIME 2 | Bioinformatic tools for processing raw 16S sequencing data, including denoising to obtain Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and taxonomic classification [3]. |

| Kraken 2 / MetaPhlAn 4 | Tools for quantifying taxonomic abundance from Whole Metagenome Shotgun (WMS) sequencing data [3]. |

| OMNIgene Gut Kit | A commercial collection kit designed to stabilize fecal microbiome samples at room temperature, useful for field studies or when immediate freezing is not possible [5]. |

| Positive Control Spikes | Non-biological DNA sequences or mock microbial communities added to samples to monitor technical performance and detect contamination throughout the sequencing workflow [5]. |

| Trijuganone B | Trijuganone B, CAS:126979-84-8, MF:C18H16O3, MW:280.3 g/mol |

| VUF10166 | VUF10166, CAS:155584-74-0, MF:C13H15ClN4, MW:262.74 g/mol |

Pathway: Navigating High-Dimensional Microbiome Data

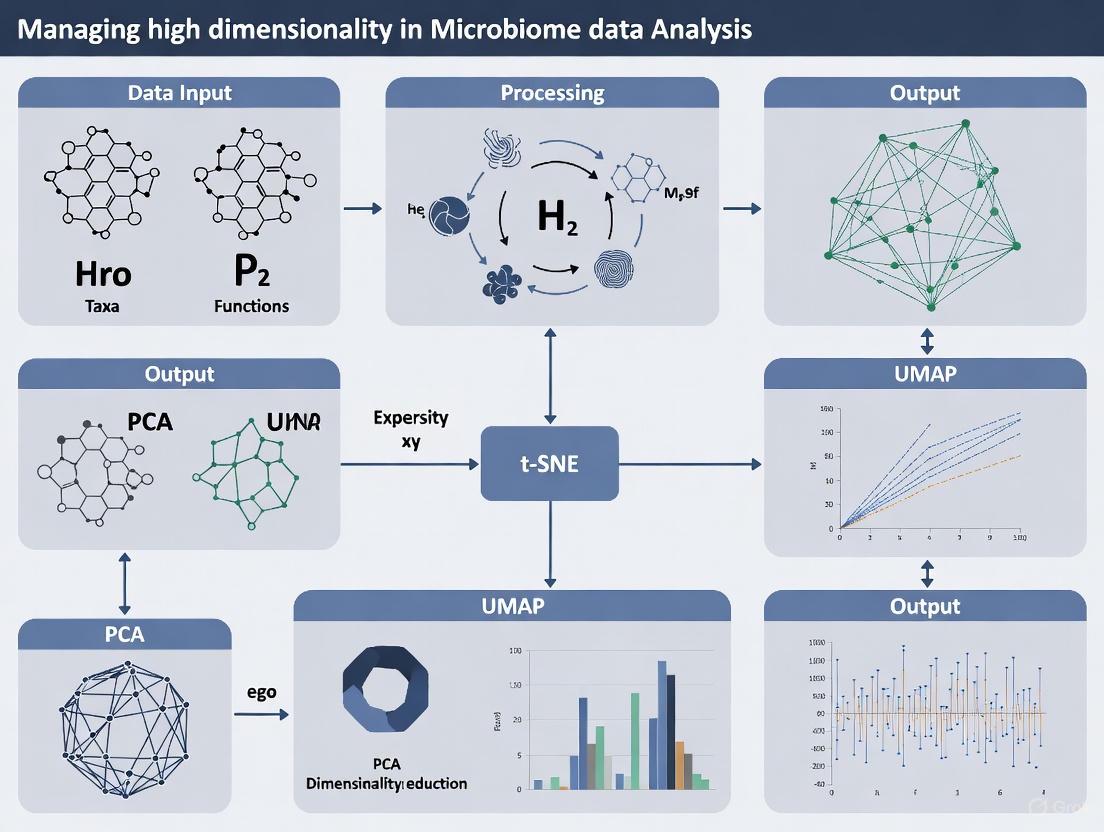

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and strategic decisions involved in tackling the 'p >> n' problem, from data characteristics to analytical solutions.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of microbiome data that create analytical challenges and the corresponding methodological approaches to address them.

| Data Characteristic | Challenge | Recommended Analytical Approach |

|---|---|---|

| High Dimensionality (p >> n) [1] [2] [3] | Overfitting, unreliable predictions, and model instability. | Regularized/penalized regression (e.g., elastic net), ensemble methods (e.g., BMA), and exploratory analysis on variable subsets [1] [2]. |

| Compositionality [3] | Relative abundances are not independent; results are difficult to interpret on an absolute scale. | Use compositional data analysis (CoDA) methods, such as centered log-ratio (CLR) transformations, or models designed for compositional data [3]. |

| Zero-Inflation [3] | Many features are absent in most samples, complicating statistical testing. | Employ models specifically designed for zero-inflated count data (e.g., zero-inflated negative binomial models) or apply prevalence filtering [3]. |

| Tree-Structured Data [3] | Microbial features are related through taxonomic or phylogenetic trees. | Leverage tree-aware methods like phylogenetic principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) using UniFrac distances to incorporate evolutionary relationships [3]. |

| Longitudinal Instability [5] [8] | Microbial communities change over time, adding complexity to study design. | Use longitudinal analysis methods (e.g., EMBED, GLM-ASCA) that can model temporal dynamics and subject-specific effects [4] [8]. |

FAQ: Understanding the Core Challenges

What makes microbiome data analysis uniquely challenging? Microbiome data from high-throughput sequencing possesses three intrinsic characteristics that complicate statistical analysis: compositionality, sparsity, and overdispersion. If not properly accounted for, these properties can lead to biased results and false discoveries [9] [10].

What does "compositionality" mean in this context? Microbiome data, often from 16S rRNA gene sequencing, is typically summarized as relative abundances. Because these values sum to a constant (e.g., 1 or 100%), they are "compositional" [10]. This means the data resides in a simplex, and an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon will cause an artificial decrease in the relative abundance of others, making it difficult to infer true biological changes [9] [10].

Why is microbiome data so sparse? Sparsity, or "zero inflation," refers to the excess of zero counts in the data, where a large proportion of microbial taxa are not detected in a large proportion of samples [10]. This can be due to biological reasons (a taxon is genuinely absent) or technical reasons (insufficient sequencing depth) [9].

What is overdispersion? Overdispersion occurs when the variance in the observed count data is greater than what would be expected under a simple statistical model, such as a Poisson distribution. This is common in microbiome data due to the inherent heterogeneity of microbial communities across samples [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosis and Solutions

Issue 1: Dealing with Compositional Data

- Problem: Your analysis is confounded by the relative nature of the data, leading to spurious correlations.

- Diagnosis: This is a fundamental property of all microbiome sequence count tables; you are likely dealing with compositional data if you are working with OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) or SV (Sequence Variant) tables from 16S or shotgun metagenomic sequencing [10].

- Solutions:

- Use Compositionally Aware Transformations: Apply transformations such as the Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) before using standard statistical or machine learning models [9].

- Employ Specialized Methods: Utilize differential abundance analysis methods designed for compositional data, such as ANCOM-II [10]. Another approach is to combine Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) with frameworks like ANOVA Simultaneous Component Analysis (ASCA), a method referred to as GLM-ASCA, which is explicitly designed to handle the characteristics of microbiome data within an experimental design [4].

Table: Summary of Methodologies for Handling Compositionality

| Method | Brief Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | A log-ratio transformation that maps compositional data from a simplex to real space [9]. | Preprocessing for standard ML models (e.g., SVM, Random Forests). |

| ANCOM-II | A statistical framework that accounts for compositionality to identify differentially abundant taxa [10]. | Differential abundance analysis. |

| GLM-ASCA | Integrates Generalized Linear Models with ANOVA Simultaneous Component Analysis to model compositionality and other data properties within an experimental design [4]. | Analyzing multivariate data from complex experimental designs (e.g., with factors like treatment and time). |

Issue 2: Managing Data Sparsity (Excess Zeros)

- Problem: A high number of zeros in your dataset, especially for low-abundance taxa, is skewing your diversity estimates and statistical models.

- Diagnosis: Examine your feature table (OTU/SV table). If a large percentage (sometimes up to ~90%) of the entries are zero, your data is sparse [10].

- Solutions:

- Pseudo-counts: Add a small positive value (e.g., 1) to all counts before log-transformation. However, be aware that this is an ad-hoc solution and the results can be sensitive to the value chosen [10].

- Advanced Modeling: Use statistical models that explicitly account for zero-inflation, such as zero-inflated models, which can differentiate between different types of zeros (e.g., structural vs. sampling zeros) [10].

Table: Strategies for Handling Sparse Data

| Strategy | Approach | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-count | Add a small constant (e.g., 0.5, 1) to all counts [10]. | Simple but ad-hoc; choice of constant can influence results. |

| Zero-inflated Models | Use probability models that distinguish between true absences and undetected taxa [10]. | More statistically sound but relies on the validity of underlying assumptions. |

| Rarefying | Subsample sequences to an even depth across all samples [10]. | Discards valid data and introduces artificial uncertainty; controversial for differential abundance testing. |

Issue 3: Addressing Overdispersion

- Problem: The variance in your count data is much larger than the mean, violating the assumptions of standard models like the Poisson regression.

- Diagnosis: Fit a simple model and check for a poor fit. Overdispersion is common in microbiome data due to biological and technical variability [4].

- Solutions:

- Generalized Linear Models (GLMs): Use models that are built for count data and can handle overdispersion. A Negative Binomial model is often a good choice for overdispersed count data, as it includes an extra parameter to model the excess variance [4].

- Integrated Frameworks: Implement pipelines like GLM-ASCA, which uses GLMs with an appropriate distribution (e.g., Negative Binomial) to model the overdispersed count data before applying multivariate analysis [4].

Table: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Microbiome Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Application in This Context |

|---|---|---|

| QIIME 2 [9] | A powerful, user-friendly platform for microbiome analysis from raw sequences to statistical analysis. | Provides access to various normalization methods and plugins for diversity analysis. |

| MetaPhlAn [11] [12] | A tool for profiling microbial community composition from metagenomic data using clade-specific marker genes. | Generates the taxonomic profiles that form the basis for subsequent analysis of sparsity and compositionality. |

| HUMAnN2 [12] | A tool for profiling the functional potential of microbial communities from metagenomic or metatranscriptomic data. | Allows researchers to move beyond taxonomy to understand community function, which is also subject to these data characteristics. |

| DADA2 [11] | A method for inferring exact amplicon sequence variants (SVs) from sequencing data. | Generates the high-resolution feature table that is the starting point for data analysis. |

| MaAsLin 2 [4] | A tool for finding associations between microbial metadata and community profiles. | Employs GLMs to account for the properties of microbiome data during association testing. |

Experimental Workflow for Managing High-Dimensional Data

The following diagram illustrates a robust analytical workflow that integrates solutions for compositionality, sparsity, and overdispersion.

Core Technology & Data Structure FAQ

What are the fundamental differences in the data generated by 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing?

The core difference lies in the scope and scale of the genetic material being sequenced. 16S rRNA sequencing is a targeted amplicon approach that selectively amplifies and sequences only the 16S ribosomal RNA gene, a ~1,500 bp genetic marker present in most prokaryotes. The resulting data structure is a table of counts for each unique 16S sequence variant (Amplicon Sequence Variants, ASVs) or clustered Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) per sample [13] [14]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomic sequencing fragments and sequences all DNA present in a sample—bacterial, viral, fungal, and host. Its data structure is a vast collection of short reads representing random fragments from all genomes in the community, which can be used to profile taxa (often at species or strain level) and simultaneously to reconstruct functional genetic potential [15] [16].

How do the resulting taxonomic profiles differ in practice?

While both methods can characterize community composition, their resolution and breadth differ significantly, as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Taxonomic and Functional Profiling Capabilities

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Taxonomic Resolution | Genus level; species level is possible but can be unreliable [16] [17] | Species and strain-level resolution [16] [17] |

| Kingdom Coverage | Primarily Bacteria and Archaea [16] | Multi-kingdom: Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Protists [16] |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect inference based on taxonomy [15] [16] | Direct characterization of functional genes and metabolic pathways [15] [16] |

| Impact of Host DNA | Minimal; host DNA is not amplified due to targeted PCR [16] | Significant; requires deeper sequencing or host DNA removal to detect microbial signal [15] [16] |

Which method is more sensitive in detecting low-abundance taxa?

Shotgun metagenomics generally has more power to identify less abundant taxa, provided a sufficient number of reads is available. A comparative study on chicken gut microbiota showed that when sequencing depth was high (>500,000 reads per sample), shotgun sequencing detected a statistically significant higher number of taxa, corresponding to the less abundant genera that were missed by 16S sequencing. These less abundant genera were biologically meaningful and able to discriminate between experimental conditions [18]. The 16S method can be limited by its reliance on primer binding and PCR amplification, which can introduce biases and reduce sensitivity for certain taxa [15].

Troubleshooting Experimental Design & Data Quality

How should I choose between 16S and shotgun sequencing for my specific sample type?

The optimal choice often depends on your sample's microbial biomass and the presence of non-microbial DNA.

Table 2: Method Selection Based on Sample Type and Research Goals

| Factor | 16S rRNA Sequencing is Preferred When: | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing is Preferred When: |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Samples with low microbial biomass and/or high host DNA (e.g., skin swabs, environmental swabs, tissue biopsies) [16] [17] | Samples with high microbial biomass and low host DNA (e.g., stool) [16] [17] |

| Research Goal | Cost-effective, broad taxonomic profiling of bacterial communities is the primary goal [13] [16] | Strain-level resolution, functional potential, or multi-kingdom analysis is required [15] [16] |

| Budget | Budget is a major constraint [16] | Budget allows for higher sequencing costs and more complex bioinformatics [15] [17] |

| DNA Input | DNA input is very low (successful with <1 ng) [16] | Higher DNA input is available (typically ≥1 ng/μL) [16] |

My 16S data seems to miss key taxa mentioned in the literature for my disease model. Is this a technical artifact?

This is a common challenge. The 16S technique captures only a part of the microbial community, often giving greater weight to dominant bacteria [17]. Discrepancies can arise from several technical factors:

- Primer Bias: The choice of which hypervariable region (e.g., V3-V4, V4) to amplify significantly impacts which taxa can be detected and classified accurately [18] [19]. No single region can perfectly distinguish all species.

- Reference Database Limitations: Taxonomic assignment in 16S analysis depends on reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes). The classification can fail if the true organism is not well-represented in the database [13] [17].

- Sparsity: 16S data is often sparser (many zero counts) and shows lower alpha diversity than shotgun data from the same sample, which can affect the detection of rare taxa [18] [17]. If your research requires a comprehensive view of the community, particularly for identifying specific disease-associated species, shotgun sequencing is the more reliable choice [17].

Why does my shotgun metagenomic data show a different abundance for a genus compared to my 16S data from the same sample?

This is a known issue, primarily driven by the fundamental differences in the techniques. Key reasons include:

- Genome Characteristics: Shotgun sequencing quantifies based on the number of sequence reads originating from a genome. Organisms with larger genomes or higher 16S rRNA gene copy numbers may be overrepresented compared to their actual cellular abundance [17]. 16S data is also affected by copy number variation.

- Technical Biases: 16S data is subject to biases from DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and primer efficiency [18]. Shotgun data can be affected by the choice of reference database used for taxonomic binning and the level of host DNA contamination [15] [17].

- Database Disagreement: The reference databases for 16S (e.g., SILVA) and shotgun (e.g., RefSeq, GTDB) are different in size, content, and curation, leading to taxonomic assignment disagreements [17]. Despite this, when considering only taxa identified by both methods, their abundances are generally positively correlated [18] [17].

Managing High-Dimensionality in Downstream Analysis

How does the high-dimensionality of microbiome data from these methods impact analysis?

Both 16S and shotgun metagenomics produce data with far more features (e.g., ASVs, genes) than samples, a hallmark of high-dimensionality [20]. For example, a single study can contain hundreds of samples but tens or even hundreds of thousands of features [20]. This creates the "curse of dimensionality," which can lead to statistical overfitting, artifactual results, and runtime issues [20]. The high dimensionality is further complicated by data sparsity (most microbes are not found in most samples) and compositionality (the data conveys relative, not absolute, abundances) [20] [4]. Dimensionality reduction is thus a core, necessary step to make analysis tractable, both for creating human-interpretable visualizations and for further statistical analysis [20].

What are the recommended strategies for dimensionality reduction with these data types?

The choice of strategy should account for the specific characteristics of microbiome data.

Table 3: Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Brief Description | Key Characteristics for Microbiome Data |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A linear technique that finds orthogonal axes of maximum variance. | Assumes linearity and Euclidean distances; can produce "horseshoe" artifacts with gradient data [20]. |

| Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) | Plots a distance matrix in low-dimensional space. | Highly flexible; can use ecological distances like Bray-Curtis or UniFrac (which incorporates phylogeny) [13] [20]. |

| ANOVA Simultaneous Component Analysis (ASCA/ASCA+) | Combines ANOVA-style effect partitioning with dimension reduction. | Powerful for complex experimental designs (e.g., time series, multiple factors) to separate sources of variation [4]. |

| Generalized Linear Models (GLM) with ASCA | Extends ASCA using GLMs instead of linear models. | Recommended for advanced users. Better handles count data, sparsity, and overdispersion inherent in microbiome sequences [4]. |

For standard beta-diversity analysis (comparing community composition between samples), PCoA with Bray-Curtis or UniFrac distances is the most widely adopted and robust approach [13] [20]. For more complex, multifactorial experiments, methods like GLM-ASCA are emerging as powerful tools to disentangle the effects of different experimental factors while respecting the nature of sequence count data [4].

Diagram 1: Comparative experimental workflows for 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit / DNeasy PowerLyzer Powersoil Kit | Standardized DNA extraction from complex samples like stool or soil [17]. | Critical for yield and reproducibility; choice can affect downstream results. |

| KAPA HiFi Hot Start DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity PCR amplification for 16S library preparation [21]. | Reduces PCR errors, crucial for generating accurate full-length 16S sequences. |

| SILVA Database | Curated database of ribosomal RNA genes for taxonomic assignment in 16S analysis [13] [17]. | A standard reference; requires periodic updating. |

| Greengenes2 Database | Alternative curated 16S rRNA gene database for taxonomic classification [13]. | |

| UHGG / GTDB Databases | Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome & Genome Taxonomy Databases for shotgun metagenomic analysis [17]. | Essential for accurate species and strain-level binning of shotgun reads. |

| QIIME 2 | A powerful, extensible, and user-friendly bioinformatics platform for 16S rRNA analysis [13]. | Integrates denoising (DADA2), taxonomy assignment, and diversity analysis. |

| DADA2 / Deblur | Algorithms for inferring exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) from 16S data [13] [21]. | Provides higher resolution than traditional OTU clustering. |

| Kraken2 / Bracken | System for fast taxonomic classification of shotgun metagenomic sequences and abundance estimation [17]. | |

| Phyloseq (R Package) | R package for the interactive analysis and graphical display of microbiome census data [13] [20]. | Integrates with core statistical functions in R. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Defined mock community of bacteria used as a positive control for both 16S and shotgun workflows [21]. | Essential for validating sequencing and bioinformatics protocols. |

| 1,2-Dibromoethane-d4 | 1,2-Dibromoethane-d4|99% Isotopic Purity|RUO | |

| Prostaglandin Bx | Prostaglandin Bx, CAS:39306-29-1, MF:C20H32O4, MW:336.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between PCoA and NMDS? PCoA (Principal Coordinates Analysis) is an eigenanalysis-based method that aims to preserve the actual quantitative distances between samples in a lower-dimensional space [22] [23]. In contrast, NMDS (Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling) is a rank-based technique that focuses only on preserving the rank-order, or qualitative distances, between samples [24] [22]. While PCoA seeks a linear representation of the original distances, NMDS is better suited for nonlinear data relationships [22].

2. When should I choose PCoA over NMDS for my microbiome data? Choose PCoA when your analysis is tied to a specific, meaningful distance metric (like Bray-Curtis or UniFrac) and you want to visualize the actual quantitative dissimilarities [25] [22]. It is also the recommended accompaniment for PERMANOVA tests [23]. PCoA is generally less computationally demanding, making it more suitable for larger datasets [24].

3. How do I interpret the "stress" value in an NMDS plot? The stress value quantifies how well the ordination represents the original distance matrix. As a rule of thumb [24]:

- Stress > 0.2: The ordination is potentially suspect and should be interpreted with caution.

- Stress < 0.1: The representation is considered fair.

- Stress < 0.05: indicates a good fit.

4. My PCoA results show negative eigenvalues. What does this mean and how can I fix it? Negative eigenvalues occur when PCoA is applied to semi-metric distance measures (like Bray-Curtis) because the algorithm is attempting to represent non-Euclidean distances in a Euclidean space [23]. Two common corrections are [23]:

- Lingoes correction: Adds a constant to the squared dissimilarities.

- Cailliez correction: Adds a constant to the dissimilarities. These adjustments to the distance matrix help avoid negative eigenvalues.

5. What does it mean if points form tight, well-separated clusters in my ordination plot? Tight clusters of points that are well-separated from other clusters often indicate distinct sub-populations or groups within your data (e.g., microbial communities from different sample types or habitats) [24]. However, if a cluster is extremely dissimilar from the rest, the internal arrangement of its points may not be meaningful [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Stress in NMDS Ordination

Problem: The stress value of your NMDS ordination is above 0.2, making the visualization unreliable [24].

Solutions:

- Increase Dimensions: Allow the algorithm to ordinate in a higher number of dimensions (e.g., from 2 to 3) to reduce stress [24].

- Check Distance Metric: Ensure the chosen distance or dissimilarity measure (e.g., Bray-Curtis, Jaccard) is appropriate for your data and research question [22].

- Multiple Runs: Execute multiple NMDS runs with different random starting configurations to ensure the solution is stable and not trapped in a local optimum [24].

Issue 2: Ordination Plot Shows Unintelligible "Horseshoe" or "Arch" Pattern

Problem: The ordination plot exhibits a strong curved pattern, which can occur in PCA and, to a lesser extent, in PCoA, often when there is an underlying ecological gradient [20].

Solutions:

- Interpret with Caution: Recognize that this pattern may reflect a latent gradient in your data (e.g., pH, time). The arch can distort the true distances between points at the ends of the gradient.

- Switch to NMDS: Consider using NMDS, which is often more robust at handling such gradients due to its rank-based approach [24].

- Use Detrending: Some software packages offer detrending functions specifically designed to remove arch effects.

Issue 3: PCoA or NMDS Plot Fails to Show Expected Group Separation

Problem: Known groups in your data (e.g., treated vs. control) do not separate in the ordination plot.

Solutions:

- Verify Group Differences: Conduct a statistical test like PERMANOVA (for PCoA) or ANOSIM (for NMDS) to objectively test for significant group differences before relying on visual separation alone [24] [23].

- Re-evaluate Distance Metric: The chosen beta-diversity metric might not be sensitive to the specific community differences driving your grouping. Experiment with different distance measures (e.g., weighted vs. unweighted UniFrac) [22].

- Check for Confounding Factors: Investigate if technical artifacts (e.g., sequencing batch effects) or other confounding variables are obscuring the biological signal [20].

Essential Workflows and Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Conducting PCoA

The following workflow outlines the key steps for performing a Principal Coordinates Analysis, from data input to visualization [25] [23].

Detailed Steps:

- Input: Start with a feature table (e.g., species counts) or a pre-computed distance matrix [25].

- Distance Matrix Calculation: Compute a pairwise distance matrix using a metric appropriate for your data (e.g., Bray-Curtis for ecological community data) [25] [22].

- Double-Centering: Transform the squared distance matrix into a similarity matrix (matrix

B) using double-centering to place the origin at the centroid of the data [25]. - Eigendecomposition: Perform an eigen decomposition on the similarity matrix

Bto obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors [25]. - Scaling: The principal coordinates are obtained by scaling the eigenvectors by the square root of their corresponding eigenvalues [25].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Select the top

kdimensions (e.g., 2 or 3) that explain the most variance for visualization [25].

Protocol 2: Iterative Workflow for Conducting NMDS

NMDS is an iterative process that requires careful evaluation to ensure a stable and meaningful solution [24].

Detailed Steps:

- Input & Ranking: Begin with a distance matrix. The algorithm substitutes the original distances with their ranks [24].

- Initial Configuration: The points (samples) are placed in the specified number of dimensions, often randomly. Using a PCoA result for initial placement can lead to a more stable solution [24].

- Iteration: The algorithm iteratively adjusts the positions of points in the low-dimensional space [24].

- Stress Calculation: In each iteration, a stress value (a measure of disagreement between the ordination distances and the original rank distances) is calculated [24].

- Convergence Check: The iterations continue until the stress value is minimized and stable. Multiple runs from different starting points are crucial to avoid local optima [24].

- Rotation: The final configuration is often rotated using PCA to maximize the scatter of points along the first axis, aiding interpretation [24].

- Interpretation: Interpret the final plot, where distances between points approximate the rank-order of their dissimilarities [24].

Comparative Analysis and Reagent Solutions

Method Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of PCoA and NMDS to guide method selection [22].

| Characteristic | Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) | Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) |

|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Distance matrix [22] | Distance matrix [22] |

| Core Principle | Eigenanalysis; preserves quantitative distances [23] | Iterative optimization; preserves rank-order of distances [24] [22] |

| Handling of Distances | Attempts to represent actual distances linearly [23] | Preserves the order of dissimilarities; robust to non-linearity [24] |

| Output Axes | Axes have inherent meaning (eigenvalues); % variance explained can be calculated [23] | Axis scale and orientation are arbitrary; focus is on relative positions [24] |

| Best for | Visualizing patterns based on a specific, informative distance metric; larger datasets [24] [22] | Complex, non-linear data where the primary interest is in the relative similarity of samples [22] |

| Fit Statistic | Eigenvalues / Proportion of variance explained [25] | Stress value [24] |

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Software Packages

This table lists essential software tools for performing PCoA and NMDS, which are critical reagents for computational research in this field.

| Tool / Package | Function | Primary Environment | Key Citation/Resource |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-bio | pcoa() function for performing PCoA |

Python | [25] |

| vegan (R package) | metaMDS() for NMDS; wcmdscale() for PCoA |

R | [24] [23] |

| QIIME 2 | Integrated pipelines for PCoA with various beta-diversity metrics | Command-line / Python | [20] [26] |

| phyloseq (R package) | Integrates with vegan for ordination and visualization |

R | [20] [26] |

| Scikit-learn | Includes PCA and MDS (metric & non-metric) implementations | Python | [22] |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common signs of batch effects in my microbiome data? The most common signs include samples clustering strongly by processing batch, rather than by biological group (e.g., disease state), in ordination plots like PCoA or NMDS. You might also see systematic differences in library sizes (total reads per sample) or in the abundance of specific taxa between batches. Statistical tests like PERMANOVA on batch labels can confirm if these group differences are significant [27] [28].

My data is from a case-control study. What is a simple, model-free method for batch correction? Percentile normalization is a non-parametric method well-suited for case-control studies. For each microbial feature (e.g., a taxon), the abundances in case samples are converted to percentiles of the equivalent feature's distribution in the control samples from the same batch. This uses the control group as an internal reference to mitigate technical variation, allowing data from multiple studies to be pooled for analysis [27].

How can I identify and remove contaminant sequences from my data? Contaminants can be detected using frequency-based or prevalence-based methods. Frequency-based methods require DNA concentration data and identify sequences that are more abundant in samples with lower DNA concentrations. Prevalence-based methods identify sequences that are significantly more common in negative control samples than in true biological samples. Tools like

decontamimplement these approaches [29].What should I do if my data has many samples with low library sizes? First, visualize the distribution of library sizes to identify clear outliers. You can then apply a filter to remove samples with library sizes below a certain threshold (e.g., the median or a pre-defined minimum) to ensure sufficient sequencing depth. After filtering, techniques like rarefaction or data transformations can be applied to control for the remaining differences in sampling depth across samples [29].

A batch effect is confounded with my biological variable of interest. What can I do? This is a challenging scenario. If the batches cannot be physically balanced by re-processing samples, advanced batch-effect correction methods that use a model to disentangle the effects may be necessary. However, caution is required, as over-correction can remove the biological signal. Methods like Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR) are designed to preserve the effects of key variables while removing batch effects [30] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Batch Effects

Batch effects are technical variations that can lead to spurious findings and obscure true biological signals. They are notoriously common in large-scale studies where samples are processed across different times, locations, or sequencing runs [30] [28].

Protocol: A Workflow for Batch Effect Management

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for handling batch effects in a microbiome study:

Assessment Techniques:

- Visual Inspection: Use ordination plots (e.g., PCoA, NMDS based on Bray-Curtis distance) to see if samples cluster by batch instead of by the biological condition of interest [27].

- Statistical Tests: Use PERMANOVA to test if the variance explained by the batch variable is significant.

- Library Size Analysis: Check for systematic differences in total read counts between batches using violin plots or histograms [29].

Correction Methods: The choice of correction method depends on your data and study design. The table below compares several common approaches.

| Method | Brief Description | Ideal Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile Normalization [27] | Non-parametric; converts case abundances to percentiles of the control distribution within each batch. | Case-control studies; model-free approach for pooling data. | Relies on having a well-defined control group in each batch. |

| Conditional Quantile Regression (ConQuR) [30] | Uses a two-part quantile regression model to remove batch effects from zero-inflated count data. | General study designs; complex data where batch effects are not uniform across abundance levels. | Preserves signals of key variables; returns corrected read counts for any downstream analysis. |

| ComBat [31] [27] | Empirical Bayes method to adjust for location and scale batch effects. | Widely used; adapted for various data types. | Originally for normally distributed data; requires log-transformation of microbiome data, which may not handle zeros well. |

| limma [27] | Linear models to remove batch effects. | Microarray-style data; when batch is not confounded with biological variables. | Similar to ComBat, may require data transformation away from raw counts. |

Guide 2: Addressing Contamination and Low-Quality Samples

Identifying Contaminants:

As implemented in tools like decontam, there are two primary strategies [29]:

- Frequency-based: Requires DNA concentration data. Contaminants are identified by an inverse correlation between sequence frequency and sample DNA concentration.

- Prevalence-based: Compares the prevalence of sequences in true samples versus negative control samples. Contaminants are significantly more prevalent in negative controls.

Handling Low-Quality Samples:

- Calculate Library Size: Determine the total counts per sample [29].

- Visualize Distribution: Plot library sizes (e.g., histogram, violin plot) to identify outliers with unusually low counts [29].

- Apply Filter: Set a justified threshold (e.g., based on distribution or experimental knowledge) and remove samples below it.

- Control for Depth: Apply rarefaction or data transformations (e.g., CSS, log-transformations) to the remaining samples to account for uneven sequencing depth [31] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|

| Negative Control Samples | Contain no biological material (e.g., sterile water) and are processed alongside real samples to identify reagent and environmental contaminants. |

| Standardized DNA Extraction Kits | Ensure consistent lysis of microbial cells and recovery of genetic material across all samples in a study, minimizing batch effects from sample preparation. |

| Internal Standards/Spike-ins | Known quantities of foreign organisms or DNA added to samples before processing. Used to calibrate measurements and account for technical variation in sequencing efficiency. |

| 6-Bromonicotinonitrile | 6-Bromonicotinonitrile, CAS:139585-70-9, MF:C6H3BrN2, MW:183.01 g/mol |

| (E/Z)-BML264 | (E/Z)-BML264, CAS:110683-10-8, MF:C21H23NO3, MW:337.4 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing ConQuR for Batch Effect Removal

ConQuR (Conditional Quantile Regression) is a comprehensive method for removing batch effects from microbiome read counts while preserving biological signals [30].

Protocol: The ConQuR Workflow

The methodology involves a two-step process for each taxon, as illustrated below:

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Organize your data into a taxa count table, with information on batch ID, key biological variables, and other relevant covariates.

- Regression Step (Two-Part Model):

- Part 1 - Logistic Regression: Models the probability that a taxon is present (non-zero) in a sample, using batch, key variables, and covariates as predictors.

- Part 2 - Quantile Regression: Models the percentiles (e.g., median, quartiles) of the taxon's abundance distribution conditional on its presence, using the same set of predictors. This non-parametrically captures the entire conditional distribution without assuming a specific shape (e.g., Normal or Negative Binomial).

- Using these models, ConQuR estimates both the original conditional distribution for each sample and a batch-free distribution by setting the batch effect to that of a chosen reference batch [30].

- Matching Step: For each sample and taxon:

- The observed read count is located within the estimated original conditional distribution to find its corresponding percentile.

- The corrected read count is then selected as the value at that same percentile in the estimated batch-free distribution.

- Output: The result is a batch-corrected count table that retains the zero-inflated, over-dispersed nature of microbiome data, suitable for any subsequent analysis like diversity measures, differential abundance testing, or prediction [30].

Key Advantages:

- Robustness: Non-parametric modeling makes it suitable for complex microbiome count distributions.

- Thorough Correction: Corrects for batch effects in both presence-absence and abundance levels, addressing mean, variance, and higher-order effects.

- Signal Preservation: Designed to preserve the effects of key biological variables during correction [30].

Advanced Analytical Arsenal: From GLMs to Machine Learning

The analysis of microbiome data presents a unique set of statistical challenges that stem from the inherent nature of sequencing technologies. Microbiome datasets are typically high-dimensional, containing far more microbial features (e.g., Operational Taxonomic Units or ASVs) than samples, a phenomenon known as the "curse of dimensionality" [20] [26]. Furthermore, the data are compositional, meaning that individual microbial abundances represent relative proportions rather than absolute counts, and are characterized by zero-inflation and over-dispersion [32] [33]. Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) provide a flexible framework for modeling such data, but their successful application requires careful consideration of these special characteristics to avoid invalid inferences and draw robust biological conclusions. This guide addresses frequent challenges and provides troubleshooting advice for researchers analyzing high-dimensional microbiome count data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I use standard linear models (e.g., ANOVA) or Poisson GLMs on raw microbiome count data?

Standard linear models assume normally distributed, continuous data with constant variance, assumptions that are violated by microbiome counts which are discrete, non-negative, and often over-dispersed [33]. A standard Poisson GLM is also often inadequate because it assumes the mean and variance are equal, whereas microbiome data frequently exhibit variance greater than the mean (over-dispersion) and an excess of zero counts [32]. Using these models without modification can lead to biased estimates and incorrect conclusions.

Q2: My model fails to converge or produces unstable coefficient estimates. What is the likely cause and how can I address it?

This is a common symptom of high-dimensionality, where the number of microbial features (p) is comparable to or larger than the number of samples (n), making the model non-identifiable [34]. Solutions include:

- Implementing Regularization: Use penalized models (e.g., lasso, elastic net) or Bayesian models with sparsity-inducing priors like the regularized horseshoe prior to shrink the effects of irrelevant taxa toward zero [34] [35].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Employ methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or its extensions to create a lower-dimensional set of features (latent variables) that can then be used in the GLM [35].

Q3: How should I handle the many zeros in my microbiome dataset?

Zeros can arise from true biological absence or technical undersampling. Simply replacing them with a small pseudo-count (e.g., 0.5) can be statistically problematic and bias results [32]. A more principled approach is to use a two-part model specifically designed for zero-inflated data, such as:

- Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) Model: This model combines a point mass at zero with a negative binomial distribution for the counts, effectively modeling the zero-inflation and over-dispersion simultaneously [32].

- Hurdle Models: These use one process to model the presence/absence of a taxon and a second, truncated count process (e.g., Poisson or Negative Binomial) to model the positive abundances.

Q4: How do I account for the compositional nature of microbiome data in a GLM?

Because microbial abundances are relative, they exist on a simplex (i.e., they sum to a constant). Applying a standard GLM directly can produce spurious correlations. The established solution is to use a log-contrast model [34]. This involves:

- Log-transforming the relative abundances (often after replacing zeros with a pseudo-count).

- Enforcing a sum-to-zero constraint on the regression coefficients associated with the microbial features. This ensures the model is invariant to the arbitrary scaling inherent in compositional data. This constraint can be implemented as a "soft-centering" through a prior in a Bayesian framework [34].

Q5: How can I incorporate complex experimental designs, such as repeated measures or multiple interacting factors?

For longitudinal studies or repeated measurements, you must account for the correlation between samples from the same subject. Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) extend the GLM framework by including random effects (e.g., a random intercept for each subject) to model this within-subject correlation [34] [36]. For complex multifactorial designs, methods like GLM-ASCA (Generalized Linear Models–ANOVA Simultaneous Component Analysis) integrate GLMs with an ANOVA-like decomposition to separate and visualize the effects of different experimental factors and their interactions on the multivariate microbial community [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Analytical Issues

Problem 1: Inaccurate Inference Due to Over-dispersion and Skewness

- Symptoms: Poor model fit, confidence intervals that are too narrow, inflated Type I error rates.

- Diagnosis: Check if the variance of the counts is much larger than the mean. Examine the residuals for patterns that suggest a misspecified variance function.

- Solutions:

- Use a Negative Binomial GLM: This is a direct extension of the Poisson model that explicitly models over-dispersion via an additional dispersion parameter [33].

- Adopt a Quasi-Likelihood Approach: Instead of assuming a specific distribution (e.g., Poisson or Negative Binomial), model the mean and specify a flexible, smooth relationship between the variance and the mean. This is particularly useful when the distribution of the data is unknown or complex [33].

- Example Workflow for Flexible Quasi-Likelihood:

- Initialize coefficients

βby fitting a model with constant variance. - Estimate the unknown, smooth variance function

V(μ)using a method like P-splines. - Update

βusing the estimated variance function in a quasi-score equation. - Iterate steps 2 and 3 until convergence [33].

- Initialize coefficients

Problem 2: Integrating Multi-Omic Data with Microbiome Features

- Symptoms: Difficulty interpreting results from multiple, high-dimensional data types (e.g., metabolomics, metagenomics) analyzed separately.

- Diagnosis: Univariate analyses of each omic dataset fail to reveal synergistic or interactive effects.

- Solution (LIVE Framework):

- Dimensionality Reduction per Omic: For each data type (e.g., taxa, metabolites), perform sparse PLS-DA (sPLS-DA) or sparse PCA (sPCA) to extract a small number of latent variables (LVs) or principal components (PCs) that capture the major patterns.

- Integrated Modeling: Use the sample projections from these LVs/PCs as predictors in a GLM. Include interaction terms between LVs/PCs from different omics to model their synergistic effects.

- Model Refinement: Apply stepwise model selection based on criteria like AIC to identify the most parsimonious and predictive model [35].

Problem 3: Analyzing Longitudinal Microbiome Data with Irregular Sampling

- Symptoms: Inability to model continuous temporal trends, loss of statistical power due to discarding samples with missing time points.

- Diagnosis: Data collection times vary across subjects, leading to an unbalanced design.

- Solution (TEMPTED Method):

- Form a Temporal Tensor: Structure your data as a 3D tensor: Subjects × Features × Continuous Time.

- Tensor Decomposition: Decompose the tensor into low-rank components. Each component consists of: a) subject loadings, b) feature loadings, and c) a smooth temporal loading function, which treats time as continuous and can handle irregular sampling.

- Downstream Analysis: Use the subject loadings for phenotype classification or the feature loadings to construct dynamic microbial trajectories for analysis [36].

Model Selection Guide & Comparative Table

The table below summarizes key GLM-based approaches for handling specific data characteristics.

Table 1: A Guide to GLM-Based Models for Microbiome Count Data

| Model / Approach | Primary Use Case / Strength | Key Features to Address | Software/Package |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial GLM [33] | Standard model for over-dispersed count data. | Over-dispersion | Built-in in R (glm.nb), DESeq2 |

| Zero-Inflated GLMs (ZINB) [32] | Data with a large excess of zero counts. | Zero-inflation, Over-dispersion | R packages pscl, glmmTMB |

| Bayesian Compositional GLMM (BCGLMM) [34] | High-dimensional data with phylogenetic structure and sample-specific effects. | Compositionality, High-dimensionality, Sparsity, Random effects | rstan (code available from publication) |

| Flexible Quasi-Likelihood (FQL) [33] | Data with complex, unknown mean-variance relationship and skewness. | Over-dispersion, Skewness, Heteroscedasticity | R package fql |

| GLM-ASCA [4] | Multivariate analysis for complex experimental designs (factors, interactions). | Experimental Design, Multivariate Structure | - |

| LIVE Modeling [35] | Integrative multi-omics analysis. | High-dimensionality, Multi-omic Integration | MixOmics R package |

| TEMPTED [36] | Longitudinal data with irregular or sparse time points. | Temporal Dynamics, Irregular Sampling | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Resources for Microbiome Analysis Workflows

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| POD5/FASTQ Files [37] | Raw and basecalled sequencing data files, the starting point for all bioinformatic analysis. |

| BAM/CRAM Files [37] | Processed and aligned sequence data files, used for variant calling and storing methylation data. |

| Feature Table (OTU/ASV Table) [20] [26] | A matrix of counts per microbial feature (e.g., ASV) per sample; the primary input for statistical modeling. |

| Modified Cary-Blair Medium [38] | A transport medium used to preserve the viability of microbes in fecal samples during shipment. |

| Pseudo-count [34] [32] | A small value (e.g., 0.5) added to all counts to allow for log-transformation of zero values; use with caution. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) [37] | A genomic sequence file used as a reference for aligning sequencing reads. |

| Structured Regularized Horseshoe Prior [34] | A Bayesian prior used for variable selection in high-dimensional settings, encouraging sparsity while accounting for potential correlations (e.g., phylogenetic). |

| ANOVA Simultaneous Component Analysis (ASCA) [4] | A framework for partitioning variance in multivariate data according to an experimental design, combined with GLMs in GLM-ASCA. |

| H-Glu-OMe | H-Glu-OMe | Glutamic Acid Derivative for Peptide Research |

| Isaxonine | Isaxonine |

Workflow Visualization: Navigating Model Selection for Microbiome Data

The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway for selecting an appropriate modeling strategy based on the characteristics of your microbiome dataset.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts and Methodology

Q1: What is GLM-ASCA, and how does it differ from standard ASCA?

GLM-ASCA is a novel method that combines Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) with ANOVA Simultaneous Component Analysis (ASCA). While standard ASCA uses linear models and is best suited for continuous, normally distributed data, GLM-ASCA extends this framework to handle the unique characteristics of microbiome and other omics data, such as compositionality, zero-inflation, and overdispersion [4]. It does this by fitting a GLM to each variable in the multivariate dataset and then performing ASCA on the working responses from the GLMs, allowing for a more appropriate modeling of count-based or non-normal data [4].

Q2: When should I consider using GLM-ASCA for my analysis?

You should consider GLM-ASCA when your data has the following characteristics:

- The data is multivariate high-dimensional (e.g., hundreds of microbial taxa or metabolites) [4] [39].

- The experimental design includes multiple factors (e.g., treatment, time, group) and their interactions [4].

- The response variables have properties that violate the assumptions of standard linear models, such as being count-based, compositional, sparse, or zero-inflated [4] [39].

- Your goal is to separate, visualize, and understand the effect of different experimental factors on the entire multivariate system [4].

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Q3: My microbiome data is compositional and sparse. How should I preprocess it before using GLM-ASCA?

Microbiome data requires careful preprocessing. The following table summarizes common normalization methods that can be applied prior to analysis with methods like GLM-ASCA [39].

| Normalization Method Category | Example Method | Brief Description | Considerations for Microbiome Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecology-based | Rarefying | Subsamples sequences to an even depth across all samples. | Can mitigate uneven sampling depth but discards data. |

| Traditional | Total Sum Scaling | Converts counts to relative abundances. | Simple but reinforces compositionality. |

| RNA-seq based | CSS, TMM, RLE | Adjusts for library size and composition using methods from RNA-seq. | May help with compositionality and differential abundance. |

| Microbiome-specific | Addressing zero-inflation, compositionality, or overdispersion. | Methods designed specifically for microbiome data characteristics. | Can be more powerful but method-dependent. |

For GLM-ASCA specifically, data is often log-transformed after adding a small pseudo-count (e.g., 0.5) to handle zeros before the GLM is fitted [34].

Model Fitting and Troubleshooting

Q4: I see strong patterns in my model's residual plots. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

Patterns in residual plots suggest model misspecification. Common causes and solutions include [40]:

- Wrong Distribution: The chosen GLM distribution (e.g., Poisson) may not fit your data. For overdispersed count data, consider a Negative Binomial distribution instead [40].

- Wrong Model Structure: The model may ignore important data structures. If your data has repeated measures or a hierarchical structure (e.g., samples from the same subject), you may need to use a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) to account for this non-independence. The related RM-ASCA+ framework is designed for such longitudinal data [41] [42].

- Inherent Sampling Bias: If your sampling method systematically excluded certain observations, the model may not be generalizable. Reconsider the scope of your inference.

- Zero-Inflated Data: An excess of zeros can cause patterns in residuals. In such cases, a zero-inflated model may be required [40].

Q5: How do I handle longitudinal or repeated measures data with GLM-ASCA?

For longitudinal studies with repeated measurements from the same subject, you should use an extension of the framework called Repeated Measures ASCA+ (RM-ASCA+) [41] [42]. This method uses repeated measures linear mixed models in the first step of ASCA+ to properly account for the within-subject correlation, which is a violation of the independence assumption in standard models. RM-ASCA+ can also handle unbalanced designs and missing data that are common in longitudinal studies [41].

RM-ASCA+ Workflow for Longitudinal Data

Interpretation and Visualization

Q6: After running a GLM-ASCA, how do I interpret the interaction effects?

In ASCA-based methods, the data variation is decomposed into matrices representing different factors (e.g., Time, Treatment) and their interactions (e.g., Time × Treatment) [4]. To interpret an interaction effect:

- Visualize the Score Plot: The PCA score plot for the interaction effect matrix shows how samples cluster based on the combined effect of the two factors. Look for separations or trajectories that are unique to specific factor-level combinations.

- Examine the Loading Plot: The corresponding loading plot identifies which variables (e.g., microbial taxa) are driving the patterns seen in the score plot. Variables located in the direction of a particular sample group are influential for that group.

- Validate the Model: Use permutation tests to assess the statistical significance of the interaction effect to ensure the observed pattern is not due to chance [4].

Experimental Design and Advanced Applications

Q7: How does experimental design (randomized vs. non-randomized) affect my GLM-ASCA model?

The study design critically influences how you specify your model, particularly regarding baseline adjustment. This is important for avoiding spurious conclusions from a phenomenon known as Lord's paradox [41] [42].

- In randomized controlled trials, groups are equal at baseline by design. Adjusting for baseline values of the response variable is recommended, as it improves the precision of the treatment effect estimate. This can be done by using a model that constrains group means to be equal at baseline [42].

- In non-randomized studies, groups may differ systematically before the intervention starts. Adjusting for baseline in this context can introduce bias. Therefore, an unadjusted model is often more appropriate [42].

Q8: Are there Bayesian alternatives to GLM-ASCA for predictive modeling with microbiome data?

Yes, Bayesian methods offer a powerful alternative, especially for prediction. For example, the Bayesian Compositional Generalized Linear Mixed Model (BCGLMM) is designed for disease prediction using microbiome data [34]. It uses a sparsity-inducing prior to identify key taxa with moderate effects and a random effect term to capture the cumulative impact of many minor taxa, often leading to higher predictive accuracy [34].

BCGLMM Model Components for Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table lists key resources for conducting a microbiome study analyzed with frameworks like GLM-ASCA.

| Item | Function / Application in Analysis |

|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Standard amplicon sequencing technique for taxonomic profiling of microbial communities [4] [39]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | Technique for assessing the collective genomic content of a microbial community, allowing for functional analysis [39]. |

| Pseudo-counts (e.g., 0.5) | Small values added to zero counts in the data matrix to allow for log-transformation, a common step in modeling compositional data [34]. |

| Reference Databases (e.g., Greengenes, SILVA) | Curated databases used for taxonomic assignment of 16S rRNA sequence reads [39]. |

| Negative Binomial Model | A type of GLM used for overdispersed count data, often more appropriate for microbiome data than Poisson [40]. |

| R or Python Software Environments | Primary computational environments with packages for implementing GLMs, PCA, and custom scripts for ASCA-based frameworks [4]. |

| Ala-Trp-Ala | Ala-Trp-Ala, CAS:126310-63-2, MF:C17H22N4O4, MW:346.4 g/mol |

| (R)-(-)-N-Boc-3-pyrrolidinol | (R)-(-)-N-Boc-3-pyrrolidinol, CAS:109431-87-0, MF:C9H17NO3, MW:187.24 g/mol |

FAQs: Choosing and Applying Dimensionality Reduction Methods

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between PCA, PCoA, NMDS, and NMF?

The core differences lie in their input data requirements, underlying distance measures, and ideal application scenarios, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Dimensionality Reduction Methods

| Characteristic | PCA | PCoA | NMDS | NMF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Original feature matrix (e.g., species abundance) [22] | Distance matrix (e.g., Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) [22] | Distance matrix [22] | Non-negative feature matrix [43] |

| Distance Measure | Covariance/Correlation matrix (Euclidean) [22] | Any ecological distance (Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, UniFrac) [22] | Rank-order of distances [22] | Kullback-Leibler divergence or Euclidean distance [43] |

| Core Principle | Linear transformation to find axes of maximum variance [22] | Projects a distance matrix into low-dimensional space [22] | Preserves rank-order of dissimilarities between samples [22] | Factorizes data into two non-negative matrices (W & H) [43] |

| Best for Data Structure | Linear data distributions [22] | Inter-sample relationships based on a chosen distance [22] | Complex, non-linear data; robust to outliers [22] | Data where components are additive (e.g., count data) [43] |

Q2: How do I know if my microbiome data is suited for PCA or if I need PCoA/NMDS?

Choose based on your data's characteristics and research question:

- Use PCA if your data has a linear structure and you want to use the original feature matrix (e.g., species abundance) with a Euclidean distance. It is ideal for feature extraction and reducing dataset dimensionality before further analysis [22].

- Use PCoA or NMDS when your analysis is based on a specialized ecological distance (e.g., Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, or UniFrac), which are better suited for capturing compositional similarities between microbial communities [22] [43]. PCoA is excellent for visualizing these inter-sample relationships [22], while NMDS is more robust for complex, non-linear data where preserving the exact distance is less critical than the rank-order [22].

Q3: I ran a PCoA and see a "horseshoe" or "arch" effect. What does this mean, and is it a problem?

The arch effect occurs when samples are arranged along a single, strong environmental gradient [44]. This artifact can appear with several distance metrics and methods, including Euclidean distance in PCA and PCoA [44]. While it confirms the presence of a major gradient, it can distort the spatial representation of samples. If you suspect multiple gradients, consider methods like NMDS, which may handle this better, though no method is entirely free from this effect [44].

Q4: My NMDS stress value is high. What should I do?

The stress value indicates how well the low-dimensional plot represents the original high-dimensional distances. Generally:

- Stress > 0.2: Potentially poor representation, interpret with caution.

- Stress < 0.1: Good representation.

- Stress < 0.05: Excellent representation. If stress is high, you can:

- Increase the number of dimensions (k): Run the NMDS with a higher k (e.g., k=3 instead of k=2) and check if the stress drops to an acceptable level.

- Check your distance measure: Ensure the chosen distance metric (Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, etc.) is appropriate for your biological question.

- Increase iterations: Allow the algorithm more iterations to converge on a stable, low-stress solution [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Separation of Sample Groups in Ordination Plot

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Weak Biological Effect: The actual differences in microbial composition between your experimental groups may be subtle. Solution: Use statistical methods like PERMANOVA to test if the group differences are significant, even if not visually obvious in the plot.

- Inappropriate Distance Metric: The chosen distance measure may not be sensitive to the biologically relevant differences in your study. Solution: Experiment with different distance measures. For instance, if you are interested in phylogenetic differences, use UniFrac distance instead of Bray-Curtis [22] [43].

- High Within-Group Variation: Technical noise or high biological variability can mask group patterns. Solution: Ensure proper data preprocessing, including filtering low-abundance taxa to reduce noise [45]. Techniques like Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation can help manage compositionality [46].

Issue: Dimensionality Reduction is Overwhelmed by a Single, Strong Factor

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Dominant Batch Effect: A strong technical batch effect can be the primary driver of variance. Solution: Apply batch effect correction methods, such as the "ComBat" function from the

svaR package, before conducting the dimensionality reduction analysis [45]. - Dominant Biological Factor: A single, overpowering biological factor (e.g., health vs. disease state) might obscure the signal of a secondary factor you are interested in (e.g., treatment response). Solution: Use a method that can account for experimental design, such as GLM-ASCA, which can separate the effects of multiple factors [4].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor group separation | Inappropriate distance metric | Switch from Euclidean/PCA to a ecological distance (e.g., Bray-Curtis) in PCoA/NMDS [22] [44] |

| High stress in NMDS | Too few dimensions | Re-run NMDS with a higher k (number of dimensions) [22] |

| Arch/Horseshoe effect | Single, strong environmental gradient | Acknowledge the gradient; use NMDS; or explore constrained ordination methods [44] |

| Uninterpretable components | High sparsity and noise in data | Filter low-abundance taxa prior to analysis [45] |

| Misleading patterns from compositionality | Relative nature of microbiome data | Apply CLR or ILR transformation before using Euclidean-based methods like PCA [46] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Executing Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) for Beta-Diversity Visualization

This protocol outlines the steps to perform PCoA using common ecological distances to visualize differences in microbial community composition (beta-diversity) between samples.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software Environment: R statistical software with

vegan,phyloseq, andapepackages. - Distance Matrices: Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity (quantitative, abundance-weighted), Jaccard Index (qualitative, presence-absence), UniFrac Distance (phylogenetic, weighted or unweighted).

- Normalization Method: For amplicon data, use a standardized subsampling (rarefaction) to even sequencing depth before calculating distances, or use a compositionally robust method like Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation.

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Start with a feature table (OTU/ASV table). Filter out low-abundance taxa (e.g., those with a mean relative abundance below 0.01%) to reduce noise [43] [45]. Normalize the data, for example, by rarefying or using a CLR transformation.

- Calculate Distance Matrix: Using the normalized feature table, compute a pairwise distance matrix between all samples. For microbial ecology, Bray-Curtis is a common and robust starting point.

- Perform PCoA: Use the calculated distance matrix to run the PCoA ordination.

- Visualize Results: Extract the PCoA axes (e.g.,

pcoa_result$points) and plot them using a scatter plot, coloring the points by your experimental groups (e.g., disease state, treatment). - Interpretation: The percent variance explained by each principal coordinate is typically found in

pcoa_result$eig. Closer points on the plot represent samples with more similar microbial communities.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this PCoA protocol.

Protocol: Benchmarking Integrative Strategies for Microbiome-Metabolome Data

This protocol is based on a systematic benchmark study that evaluated methods for integrating two omic layers, such as microbiome and metabolome data [46].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Simulation Framework: Normal to Anything (NORtA) algorithm to generate data with arbitrary marginal distributions and correlation structures based on real data templates.

- Data Transformations: Centered Log-Ratio (CLR), Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR) for compositional microbiome data; log transformation for metabolomics data.

- Method Categories: Global association (Procrustes, Mantel test), Data summarization (CCA, PLS, MOFA2), Individual associations (Sparse CCA/PLS), Feature selection (LASSO).

Methodology:

- Data Simulation: Use a realistic simulation approach like the NORtA algorithm to generate paired microbiome and metabolome datasets. Use real datasets (e.g., from diseases like Konzo or CRC) as templates to capture realistic correlation structures and marginal distributions (e.g., negative binomial for microbiome, Poisson or log-normal for metabolome) [46].

- Define Analysis Goals: Categorize the research question into one of four aims:

- Global Association: Test for an overall association between the two datasets.

- Data Summarization: Find low-dimensional representations that summarize shared variance.

- Individual Associations: Identify specific microbe-metabolite pairs.

- Feature Selection: Pinpoint the most relevant, non-redundant features across datasets.

- Apply Integrative Methods: For each aim, apply a suite of methods. For example, for global association, apply Procrustes analysis and the Mantel test. For data summarization, apply Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) or Partial Least Squares (PLS) [46].

- Performance Benchmarking: Evaluate methods based on power, robustness, and interpretability. Use metrics like correlation quality for gradients, cluster separation for discrete groups, and sensitivity/specificity for association detection against the known ground truth from simulations [46] [44].

- Validation on Real Data: Apply the top-performing methods identified in the simulation to a real paired microbiome-metabolome dataset to uncover biological insights.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dimensionality Reduction Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools / Packages |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Distance Metrics | Quantify dissimilarity between microbial communities based on composition or phylogeny. | Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, UniFrac [22] [43] |

| Compositional Data Transformations | Mitigate the artifacts arising from the relative nature of microbiome data. | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR), Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR) [46] |

| Batch Effect Correction Tools | Remove unwanted technical variation to reveal true biological signal. | ComBat (from sva R package) [45] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Build predictive models or perform feature selection on high-dimensional microbiome data. | Ridge Regression, Random Forest, LASSO [45] |

| Specialized R Packages | Provide integrated workflows for microbiome data analysis and visualization. | vegan, phyloseq, mare [20] |

| Simulation Frameworks | Generate synthetic data with known ground truth for method benchmarking. | NORtA algorithm [46] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Q: My microbiome classification model's performance is poor. Could the issue be with how I've normalized my data?

A: Poor performance can often be traced to inappropriate data normalization. Microbiome data is compositional, high-dimensional, and sparse, which requires specific normalization approaches [47] [48] [49]. The best normalization technique can depend on your chosen classifier.

Investigation Steps:

- Systematically compare the performance of different normalization methods on your validation set.