Optimizing Hyperparameter Selection for Microbial Network Inference: A Cross-Validation Framework for Robust and Interpretable Results

Hyperparameter selection is a critical yet challenging step in inferring accurate and biologically relevant microbial co-occurrence networks from high-dimensional, sparse microbiome data.

Optimizing Hyperparameter Selection for Microbial Network Inference: A Cross-Validation Framework for Robust and Interpretable Results

Abstract

Hyperparameter selection is a critical yet challenging step in inferring accurate and biologically relevant microbial co-occurrence networks from high-dimensional, sparse microbiome data. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians, covering the foundational principles of network inference algorithms and their hyperparameters. It details advanced methodological approaches, including novel cross-validation frameworks and algorithms designed for longitudinal and multi-environment data. The content offers practical strategies for troubleshooting common issues like data sparsity and overfitting and presents rigorous validation techniques to compare algorithm performance. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to make informed decisions in hyperparameter tuning, ultimately leading to more reliable insights into microbial ecology and host-health interactions for drug development and clinical applications.

The Foundation of Microbial Networks: Understanding Algorithms and Their Hyperparameters

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary biological significance of constructing microbial co-occurrence networks? Microbial co-occurrence networks are powerful tools for inferring potential ecological interactions within microbial communities. They provide insights into ecological relationships, community structure, and functional potential by identifying patterns of coexistence and mutual exclusion among microorganisms. These networks help researchers understand microbial partnerships, syntrophic relationships, keystone species, and network topology, offering a systems-level understanding of microbial communities that is crucial for predicting ecosystem functioning and responses to environmental changes [1] [2].

Q2: How do hyperparameter choices in data preprocessing affect network inference? Hyperparameter selection during data preprocessing significantly impacts network structure and biological interpretation. Key considerations include:

- Taxonomic Agglomeration: Choosing between ASVs (higher resolution) versus 97% similarity OTUs (reduces dataset size) affects node representation and ecological interpretation [2].

- Prevalence Filtering: Applying prevalence thresholds (typically 10-60% across samples) balances inclusivity of rare taxa against false-positive associations from zero-inflated data [2].

- Data Transformation: Using center-log ratio transformation is crucial for addressing compositional data bias and avoiding spurious correlations [2].

Q3: What are the main methodological approaches for inferring microbial co-occurrence networks? The two primary methodological frameworks are:

- Correlation-based Methods: These include Spearman's and Pearson's correlations, SparCC (which accounts for compositionality), and the maximal information coefficient (MIC). They measure pairwise association strengths between taxa [2] [3].

- Graphical Probabilistic Models: Methods like SPIEC-EASI use inverse covariance estimation to infer conditional dependencies, potentially providing more robust inference of direct interactions [2] [4].

Q4: How can researchers validate whether inferred networks reflect true biological interactions? Validation remains challenging but can be approached through:

- Experimental co-cultivation of strongly connected taxa to test predicted interactions [2]

- Integration with additional data types (metagenomics, metatranscriptomics) to assess functional relationships

- Applying stability analysis to network structures across different parameter choices [2]

- Comparing network topologies with known microbial ecology principles and previously verified interactions [5]

Q5: Why might the same analytical approach yield different network structures across studies? Variability arises from multiple sources:

- Differences in sequencing depth, primer selection, and preprocessing pipelines [6] [2]

- Ecological context differences (environmental conditions, disturbance regimes) [7] [4]

- Sample size effects on statistical power for correlation detection [3]

- Choices in association thresholds and statistical significance criteria [3]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Network Overly Dense with Potential False Positives

Problem: The inferred network contains an unrealistically high number of connections, potentially reflecting spurious correlations rather than biological relationships.

Solutions:

- Apply more stringent prevalence filtering (increase from 10% to 20-30% across samples) to reduce zero-inflation artifacts [2]

- Implement compositionally robust methods like SparCC or SPIEC-EASI instead of standard correlation measures [2] [4]

- Adjust association thresholds based on permutation testing or false discovery rate correction

- Verify that data has been properly transformed using center-log ratio to address compositionality [2]

Diagnostic Table: Indicators of Potential False Positives

| Indicator | Acceptable Range | Problematic Range | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of zeroes in OTU table | <80% | >80% | Increase prevalence filtering threshold |

| Correlation between abundance and degree | Weak (<0.1) | Strong (>0.3) | Apply compositionally robust method [4] |

| Network density compared to random | Moderately higher | Extremely higher (>5x) | Adjust statistical thresholds [2] |

| Module separation (modularity score) | 0.4-0.7 | <0.3 | Review data normalization approach |

Issue 2: Network Lacks Biologically Meaningful Structure

Problem: The inferred network appears random or overly fragmented without coherent modular organization.

Solutions:

- Check sample size adequacy - networks typically require dozens to hundreds of samples for robust inference [2] [3]

- Reduce stringency of association thresholds to capture weaker but biologically relevant relationships

- Examine whether over-filtering of low-abundance taxa has removed ecologically important community members [7]

- Verify that technical artifacts (batch effects, sequencing errors) aren't obscuring biological patterns

Experimental Protocol: Network Stability Assessment

- Construct multiple networks across a range of key hyperparameters (prevalence thresholds, association cutoffs)

- Calculate stability metrics (Jaccard similarity of edges, consistency of modular structure)

- Identify hyperparameter ranges where topological properties stabilize

- Select parameters from stable regions for final analysis [2]

Issue 3: Inconsistent Results Across Taxonomic Levels

Problem: Network topology changes substantially when analyzing at different taxonomic resolutions (e.g., ASV vs. genus level).

Solutions:

- Consider the ecological question - finer resolutions may detect strain-level interactions, while coarser levels reveal broader ecological patterns [3]

- Implement cross-level validation by checking if strong associations at finer resolutions persist at coarser levels

- Align taxonomic level with biological plausibility - closely related taxa often share similar ecological niches

Issue 4: Difficult Biological Interpretation of Network Topology

Problem: Despite obtaining a statistically robust network, extracting biologically meaningful insights remains challenging.

Solutions:

- Focus on topological metrics with established ecological interpretation (modularity, betweenness centrality, degree distribution) [7] [2]

- Integrate metadata (environmental parameters, process rates) to contextualize network patterns [7]

- Identify and characterize putative keystone taxa (high betweenness centrality connectors) [7] [5]

- Compare network properties with known microbial ecology principles and previous studies

Hyperparameter Selection Framework

Data Preparation Hyperparameters

Table: Critical Data Preparation Decisions and Their Impacts

| Hyperparameter | Typical Range | Impact on Network Inference | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence filtering | 10-60% of samples | Higher values reduce false positives but may exclude rare biosphere [2] | Start at 20%, test sensitivity across 10-30% range |

| Read depth (rarefaction) | Varies by dataset | Uneven sampling can bias associations; rarefaction affects methods differently [2] | Use method-specific recommendations (e.g., avoid for SparCC) |

| Taxonomic level | ASV to Phylum | Finer levels detect specific interactions; coarser levels reveal broad patterns [3] | Align with research question; genus often provides balance |

| Zero handling | Presence/absence or abundance | Influences detection of negative associations; abundance more informative but zero-inflated [2] | Use abundance with compositionally robust methods |

Network Construction Hyperparameters

Table: Association Method Selection Guide

| Method Type | Compositional Adjustment | Strengths | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based (Spearman/Pearson) | No, requires separate transformation | Simple, fast | Spurious correlations from compositionality [2] | Initial exploration, large datasets |

| SparCC | Yes, inherent | Robust to compositionality | Computationally intensive [2] | Most 16S datasets |

| SPIEC-EASI | Yes, inherent | Conditional independence, sparse solutions | Complex implementation [4] | Hypothesis-driven analysis |

| CoNet | Optional | Multiple measures combined | Multiple testing challenges [2] | Comparative network analysis |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Microbial Co-occurrence Network Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Processing | QIIME2 [6] | End-to-end processing of raw sequences | Steep learning curve but comprehensive |

| Mothur [6] | 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis | Established pipeline with extensive documentation | |

| DADA2 [2] | ASV inference from amplicon data | Higher resolution than OTU-based approaches | |

| Network Inference | SPIEC-EASI [4] | Compositionally robust network inference | Requires understanding of graphical models |

| SparCC [2] | Correlation-based with compositionality correction | Less computationally intensive than SPIEC-EASI | |

| CoNet [2] | Multiple correlation measures combined | Provides ensemble approach | |

| Network Analysis & Visualization | igraph (R/Python) | Network analysis and metric calculation | Programming skills required |

| Cytoscape [2] | Network visualization and exploration | User-friendly but limited for very large networks | |

| microeco R package [8] | Comparative network analysis | Specifically designed for microbiome data |

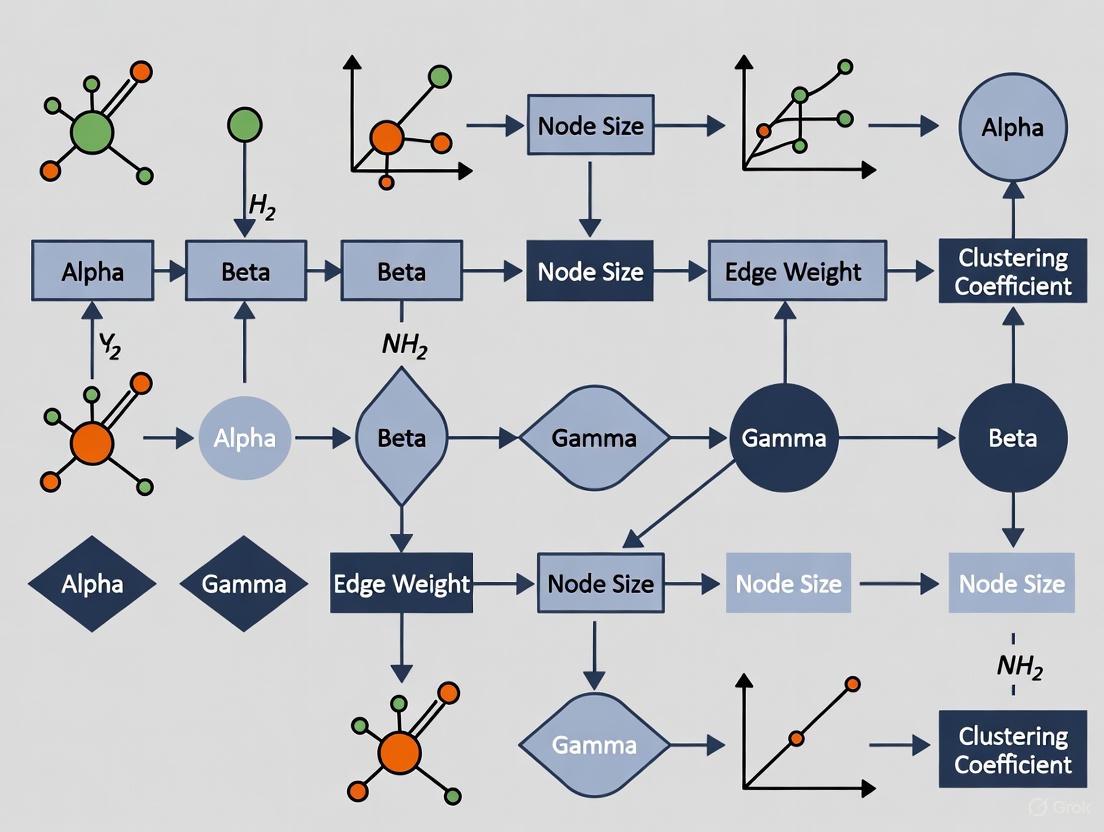

Workflow Visualization

Microbial Co-occurrence Network Analysis Workflow

Network Inference Method Selection Logic

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental differences between correlation-based, LASSO-based, and graphical model-based network inference?

- Correlation-based methods (e.g., co-occurrence networks) infer connections based on simple pairwise associations (e.g., Pearson correlation). They are computationally simple but cannot distinguish between direct and indirect interactions, often leading to spurious edges.

- LASSO-based methods use the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator to perform regularized regression. For each variable, they predict its value based on all others, shrinking small coefficients to zero. This results in a sparse network where edges represent direct interactions, helping to control false positives [9].

- Graphical Model-based methods, such as Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs), define a network where edges represent conditional dependence. In a GGM, an edge exists between two nodes if they are correlated after accounting for all other variables in the network. This directly controls for confounding and is a more robust indicator of direct relationships [9] [10].

FAQ 2: How does the problem of network "inferability" affect my results, and how can I assess it?

Network inference is often an underdetermined problem, meaning the available data may not contain enough information to uniquely reconstruct the complete, true network. Some connections may be non-inferable [11]. This has critical consequences:

- Performance Assessment: Traditional metrics that compare your inferred network to a gold standard might penalize your method for missing non-inferable edges, giving an unfairly low performance score [11].

- Interpretation: It implies that some edges in a gold-standard network might be impossible to recover from your specific dataset, regardless of the inference algorithm used.

- Assessment Strategy: To cope with this, newer assessment procedures identify which parts of the network are inferable from the data (e.g., based on causal inference and the data's perturbation structure) and then calculate performance metrics only on the inferable subset of edges [11].

FAQ 3: My LASSO-inferred network is unstable. How can I quantify uncertainty in the estimated edges?

Standard LASSO estimates are biased and do not come with natural confidence intervals or p-values, making uncertainty quantification problematic [9]. Several advanced methods address this:

- Desparsified/Debiased Lasso: This method corrects the bias of the LASSO estimate, producing an approximately unbiased estimator that can be used to derive p-values and confidence intervals for each edge [9].

- Bootstrap Methods: Applying a bootstrapped version of the desparsified lasso can provide robust confidence intervals, making it one of the recommended choices for selection and uncertainty quantification [9].

- Multi-Split Method: This method uses data-splitting to obtain p-values for the selected edges, offering another way to control for false discoveries [9].

FAQ 4: When should I choose a statistical inference approach over a machine learning approach for microbial network inference?

The choice depends on your primary analysis goal [12]:

- Choose Statistical Inference when your goal is parameter estimation or hypothesis testing. For example, use it if you need to understand the specific strength of an interaction, test if a particular environmental variable significantly alters the network, or if you have strong prior knowledge about the microbial processes you want to model [12].

- Choose Machine Learning when your goal is prediction. Use it if you want to predict a microbial phenotype (e.g., virulence, metabolite production) from genomic data or if you are dealing with very high-dimensional data and your main concern is predictive accuracy, even if the model is a "black box" [12].

- Hybrid approaches that combine both are increasingly popular, using ML for powerful pattern recognition and statistical models for interpretable parameter estimates [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance and High False Positive Rates

Problem: Your inferred network contains many connections that are not biologically plausible, or performance metrics against a known network are low.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Hyperparameter (λ) | Plot the solution path (number of edges vs. λ). Use cross-validation to find λ that minimizes prediction error. | For LASSO, use cross-validation to select the optimal λ. Consider the "1-standard-error" rule to choose a simpler model [9]. |

| Non-Inferable Network Parts | Check if your experimental data (e.g., knock-out/knock-down) provides sufficient information to infer all edges. | Focus assessment on the inferable part of the network [11]. Design experiments with diverse perturbations to maximize inferable interactions. |

| Violation of Model Assumptions | Check if data meets assumptions (e.g., Gaussianity for GGMs, sparsity for LASSO). | Pre-process data (e.g., transform, normalize). For non-Gaussian data, consider non-paranormal methods or Copula GGMs. |

| High Dimensionality (p >> n) | The number of variables (p, e.g., species/genes) is much larger than the number of samples (n). | Use methods designed for high-dimensional settings (e.g., GLASSO). Apply more aggressive regularization and prioritize sparsity. |

Issue 2: Computationally Intensive or Infeasible Runtime

Problem: The network inference algorithm takes too long to run or fails to complete.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large Number of Variables (p) | Note the computational complexity: LASSO for GGMs is O(pâ´) or worse. | For large p (e.g., >1000), use fast approximations (e.g., neighborhood selection with parallelization). Start with a smaller, representative subset of variables. |

| Inefficient Algorithm Implementation | Check if you are using optimized libraries (e.g., glmnet in R, scikit-learn in Python). |

Switch to specialized, efficient software packages for network inference. Ensure your software and libraries are up-to-date. |

| Complex Model | Using a very flexible but slow model (e.g., Bayesian models) when a simpler one would suffice. | If the goal is exploratory analysis, start with a faster method like correlation with a stringent threshold. Reserve complex models for final, confirmatory analysis. |

Issue 3: Difficulty in Hyperparameter Selection and Model Tuning

Problem: It is unclear how to choose the right hyperparameters (e.g., λ in LASSO) for your specific microbial dataset.

Solution Protocol: A Framework for Hyperparameter Selection

- Define the Goal: Decide if you prioritize high precision (few false positives) or high recall (few false negatives). In microbial networks, precision is often preferred for interpretability.

- Use Cross-Validation (CV):

- Randomly split your data into k folds (e.g., 5 or 10).

- For a candidate hyperparameter λ, train the model on k-1 folds and predict on the held-out fold.

- Repeat for all folds and compute the average prediction error.

- Select the λ value that minimizes the cross-validated error [9].

- Employ the "1-Standard-Error Rule": For a more robust and sparser network, select the most regularized model (largest λ) whose error is within one standard error of the minimum error from CV.

- Validate with Stability Selection: Repeat the inference process on multiple resampled datasets. Retain only those edges that appear consistently across these runs. This method is less sensitive to the exact choice of λ.

- Incorbrate Prior Knowledge (if available): If known microbial interactions are available, tune hyperparameters to maximize the recovery of these known edges.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Network Inference

This table details key computational tools and data types used in microbial network inference experiments.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Data | mRNA expression levels used to infer co-regulation and interactions. | The primary data source for Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) inference. Can be from microarrays or RNA-seq [11]. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Data | Profiles microbial community composition. Used to infer co-occurrence or ecological interaction networks. | The standard data source for microbial taxonomic abundance in amplicon-based studies. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Data | Provides full genomic content. Used for pangenome analysis and k-mer based inference. | Encoded as k-mers or gene presence/absence for predicting phenotypes like antimicrobial resistance [12]. |

| Perturbation Data (KO/KD) | Data from gene Knock-Out or Knock-Down experiments. Provides causal information for network inference. | Critical for assessing and improving network inferability, as it helps distinguish direct from indirect effects [11]. |

| GeneNetWeaver (GNW) | Software for in silico benchmark network generation and simulation of gene expression data. | Used to create gold-standard networks and synthetic data for objective method evaluation (e.g., in DREAM challenges) [11]. |

| Stability Selection | A resampling-based algorithm that improves variable selection by focusing on frequently selected features. | Used in conjunction with LASSO to create more stable and reliable networks, reducing false positives. |

| Desparsified Lasso | A statistical method for debiasing LASSO estimates to obtain valid p-values and confidence intervals. | Applied after network estimation to quantify the uncertainty of individual edges [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Inferring a Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM) with LASSO

This protocol details the steps for inferring a microbial association network from abundance data using the LASSO.

Methodology:

- Data Collection & Preprocessing: Collect a sample-by-species (or gene) abundance matrix. Preprocess the data: normalize for sequencing depth (e.g., CSS, TSS), transform (e.g., log, CLR), and filter out low-prevalence features.

- Model Setup (Neighborhood Selection): For each variable (node) i in the network, set up a linear regression where Xᵢ is predicted by all other variables Xⱼ (j ≠i). The regression coefficients βᵢⱼ are proportional to the partial covariances in the precision matrix [9].

- LASSO Estimation: Solve the regression for each node i using LASSO regularization. The LASSO estimator is found by minimizing:

(1/(2n)) * ||Xᵢ - ∑_{j≠i} Xⱼβᵢⱼ||² + λ * ∑_{j≠i} |βᵢⱼ|, where λ is the regularization hyperparameter [9]. - Network Reconstruction: Stitch the individual neighborhoods together to form the full network. A connection (edge) between node i and j is included if βᵢⱼ ≠0 or βⱼᵢ ≠0 (non-symmetric) or if a symmetric rule (AND/OR) is applied.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use 10-fold cross-validation on the prediction error to select the optimal λ value. The "1-standard-error" rule is recommended for a sparser, more robust network.

- Uncertainty Quantification (Optional but Recommended): Apply a method like the desparsified lasso to the selected model to obtain p-values for each edge, allowing for control of the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [9].

Protocol 2: Assessment Procedure Accounting for Network Inferability

This protocol outlines how to fairly evaluate the performance of a network inference method when the true network is only partially inferable from the data.

Methodology:

- Generate/Obtain Gold Standard and Data: Start with a known gold-standard network (e.g., from a database or simulated with GNW) and corresponding simulated experimental data (e.g., wild-type, knock-out) [11].

- Determine Inferable Edges: Based on the provided experimental data (types and number of perturbations), computationally determine which edges in the gold standard are inferable and which are non-inferable. This often relies on principles of causal inference and the structure of the perturbation graph [11].

- Run Inference Methods: Apply one or more network inference algorithms to the experimental data to obtain predicted networks.

- Calculate Modified Confusion Matrix: When comparing a predicted network to the gold standard, calculate the confusion matrix only on the subset of inferable edges. This prevents penalizing methods for missing edges that were impossible to infer [11].

- True Positives (TP): An inferable gold-standard edge that is correctly predicted.

- False Positives (FP): A predicted edge that is not in the set of inferable gold-standard edges.

- False Negatives (FN): An inferable gold-standard edge that is missing in the prediction.

- Compute Performance Metrics: Calculate standard metrics like AUROC and AUPR, but based on the modified confusion matrix from Step 4. This provides a more accurate assessment of an algorithm's performance [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most common cause of a network that is too dense and full of spurious correlations? This is frequently due to an improperly set sparsity control hyperparameter and a failure to account for the compositional nature of microbiome data. Methods that rely on simple Pearson or Spearman correlation without a sufficient threshold or regularization will often infer networks where most nodes are connected, many of which are false positives driven by data compositionality rather than true biological interactions [13] [14].

2. How can I choose a threshold for my correlation network if I don't want to use an arbitrary value? Instead of an arbitrary threshold, use data-driven methods. Random Matrix Theory (RMT), as implemented in tools like MENAP, can determine the optimal correlation threshold from the data itself [14]. Alternatively, employ cross-validation techniques designed for network inference to evaluate which threshold leads to the most stable and predictive network structure [14].

3. My network results are inconsistent every time I run the analysis on a slightly different subset of my data. How can I improve stability? This instability often stems from high-dimensionality (many taxa, few samples) and sensitivity to rare taxa. To address this:

- Apply a prevalence filter to remove taxa present in only a small percentage of samples [15] [16].

- Use sparsity-promoting methods like LASSO or sparse inverse covariance estimation (e.g., in SPIEC-EASI) that are designed for robust inference in underdetermined systems [13] [14].

- Utilize the new cross-validation framework for co-occurrence networks to select hyperparameters that yield the most stable network across data subsamples [14].

4. What is the fundamental difference between a hyperparameter for sparsity in a correlation method versus a graphical model method?

- Correlation Methods (e.g., SparCC): The sparsity hyperparameter is typically a hard threshold on the correlation coefficient (e.g., |r| > 0.6). All edges above the threshold are kept; all others are discarded [14].

- Graphical Model/Regression Methods (e.g., LASSO, SPIEC-EASI): The sparsity hyperparameter (e.g., λ in LASSO) is a regularization strength parameter. It penalizes model complexity, gradually shrinking weaker edge weights to zero in a continuous optimization process. This often provides a more robust and statistically principled sparse solution [13] [14].

5. Should I regress out environmental factors before network inference? This is a key decision. Several strategies exist, each with trade-offs [15]:

- Environment-as-node: Include environmental factors as additional nodes in the network (e.g., in CoNet, FlashWeave). This shows how the environment structures the community [15].

- Sample Stratification: Build separate networks for groups of samples from similar environments (e.g., healthy vs. diseased). This reduces environmentally-induced edges but requires sufficient sample size per group [15].

- Regression: Regress out environmental factors from the abundance data before inference. This can be powerful but risks overfitting if the microbial response to the environment is nonlinear [15]. There is no single "best" strategy; the choice should align with your specific research question [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Network is too dense and uninterpretable. Solution: Apply stronger sparsity control.

- For Correlation-Based Methods: Increase your correlation threshold. Use data-driven methods like Random Matrix Theory to find an appropriate value instead of guessing [14].

- For Regularization-Based Methods: Increase the regularization strength (e.g., the λ parameter in LASSO or GLASSO). This will force more edge weights to zero. Use cross-validation to find a λ value that minimizes prediction error or maximizes network stability [14].

- Pre-process Data: Aggressively filter rare taxa with low prevalence or abundance. A high number of zeros in the data can lead to spurious connections [15] [16].

Problem: Network is too sparse and misses known interactions. Solution: Relax sparsity constraints and check data preprocessing.

- For Correlation-Based Methods: Lower the correlation threshold and adjust the p-value or q-value significance cutoff [16].

- For Regularization-Based Methods: Decrease the regularization strength (λ). The

SPIEC-EASIframework, for instance, provides model selection criteria like the StARS (Stability Approach to Regularization Selection) to help choose a λ that balances sparsity and stability [13]. - Check Transformation: Ensure the data transformation method (e.g., Centered Log-Ratio - CLR) is appropriate for your inference algorithm. An incorrect transformation can weaken true signals [16].

Problem: Network is unstable and changes drastically with minor data changes. Solution: Improve the robustness of inference.

- Increase Sample Size: If possible, collect more samples. Network inference is notoriously difficult when the number of taxa (p) is much larger than the number of samples (n) [13].

- Use Stability-Based Selection: Employ methods like StARS in

SPIEC-EASI, which selects the regularization parameter based on the stability of the inferred edges under subsampling of the data [13]. - Leverage Cross-Validation: Use the recently proposed cross-validation method for training and testing co-occurrence networks. This framework helps in hyperparameter selection (training) and comparing the quality of inferred networks (testing), leading to more stable and generalizable results [14].

Problem: Suspect that environmental confounders are driving network structure. Solution: Actively control for confounding factors.

- Stratify Your Analysis: Split your dataset by the major environmental variable (e.g., pH, disease state, body site) and build separate networks for each stratum. This allows you to see interactions specific to each environment [15].

- Include Covariates: Use a method like

FlashWeaveorCoNetthat can incorporate environmental factors directly as nodes during network inference [15]. - Infer on Residuals: Regress out the effect of continuous environmental variables from your abundance data and perform network inference on the residuals. This attempts to isolate the biotic interactions from the abiotic responses [15].

Experimental Protocols for Hyperparameter Selection

Protocol 1: Cross-Validation for Network Inference Hyperparameter Training

This protocol is based on a novel cross-validation method designed specifically for evaluating co-occurrence network inference algorithms [14].

- Objective: To select the optimal sparsity hyperparameter (e.g., correlation threshold, regularization strength λ) for a given dataset and algorithm.

- Materials: A microbiome abundance table (OTU or ASV table) that has been preprocessed (e.g., filtered for rare taxa).

- Method Steps:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the dataset into K folds (e.g., K=5 or K=10).

- Iterative Training and Testing: For each candidate hyperparameter value:

- For k = 1 to K:

- Hold out fold k as the test set.

- Use the remaining K-1 folds as the training set.

- Infer a network on the training set using the candidate hyperparameter.

- Use the inferred network to predict the held-out test data. The specific prediction method depends on the algorithm (e.g., using partial correlations for GGMs) [14].

- Calculate the average prediction error across all K folds.

- For k = 1 to K:

- Hyperparameter Selection: Choose the hyperparameter value that results in the lowest average prediction error.

- Interpretation: This method provides a data-driven way to select a hyperparameter that generalizes well, preventing overfitting to the specific dataset and producing more robust networks [14].

Protocol 2: Stability Approach to Regularization Selection (StARS)

This protocol is used in conjunction with sparse inference methods like SPIEC-EASI [13].

- Objective: To select a regularization parameter λ that yields a sparse and stable network.

- Materials: A transformed (e.g., CLR) microbiome abundance table.

- Method Steps:

- Subsampling: For a given λ, take multiple random subsamples (e.g., N=20) of the data without replacement, each of size b (e.g., b = 10√n, where n is the total sample number).

- Network Inference: Infer a network for each subsample using the λ value.

- Stability Calculation: Calculate the pairwise stability of every possible edge across all subsampled networks. Compute the overall "instability" of the network for this λ.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1-3 for a range of λ values.

- Selection: Select the smallest λ (least regularization) that results in an instability below a pre-specified threshold (e.g., 0.05). This chooses the densest network that is still stable.

- Interpretation: StARS prioritizes the reproducibility of edges. A network is considered stable if its structure does not change significantly with small perturbations in the input data [13].

Algorithm Comparison and Hyperparameters

Table 1: Key Network Inference Algorithms and Their Sparsity Hyperparameters

| Algorithm Category | Example Methods | Sparsity Control Hyperparameter | Mechanism of Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | SparCC [14], MENAP [14] (uses RMT) | Correlation Threshold | A hard cutoff; edges with absolute correlation below the threshold are removed. | Simple but can be arbitrary. RMT offers a data-driven threshold. Sensitive to compositionality. |

| Regularized Regression | CCLasso [14], REBACCA [14] | L1 Regularization Strength (λ) | Shrinks the coefficients of weak associations to exactly zero. | Provides a principled sparse solution. λ is typically chosen via cross-validation. |

| Gaussian Graphical Models (GGM) | SPIEC-EASI [13] [14], MAGMA [14] | L1 Regularization Strength (λ) | Enforces sparsity in the estimated precision matrix (inverse covariance), inferring conditional dependencies. | Infers direct interactions by accounting for indirect effects. SPIEC-EASI is compositionally robust [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Microbial Network Inference

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Hyperparameter Controls |

|---|---|---|

| SPIEC-EASI [13] | Infers microbial ecological networks from amplicon data, addressing compositionality and high dimensionality. | Method (MB vs. GLASSO), Regularization strength (λ), Pulsar threshold (for StARS). |

| MetagenoNets [16] | A web-based platform for inference and visualization of categorical, integrated, and bi-partite networks. | Correlation algorithm (SparCC, CCLasso, etc.), P-value/Q-value thresholds, Prevalence filters. |

| CCLasso [14] | Infers sparse correlation networks for compositional data using least squares and penalty. | Regularization parameter (λ) to control sparsity. |

| SparCC [14] | Estimates correlation values from compositional data and uses a threshold to create a network. | Correlation threshold, Iteration threshold for excluding outliers. |

| CoNet [15] [14] | A network inference tool that can integrate multiple correlation measures and environmental data. | Correlation threshold, P-value cutoffs, Combination method for multiple measures. |

| Glypinamide | Glypinamide | High-Purity Research Compound | Glypinamide for research applications. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Trabodenoson | Trabodenoson, CAS:871108-05-3, MF:C15H20N6O6, MW:380.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

� Experimental and Logical Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making process for selecting and tuning hyperparameters in microbial network inference, integrating the troubleshooting concepts from the guides above.

This workflow provides a logical pathway for diagnosing and resolving common hyperparameter-related issues in network inference.

The Critical Impact of Hyperparameter Choices on Network Structure and Biological Interpretation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My microbial co-occurrence network shows unexpected positive correlations. Could this be a hyperparameter issue? Yes, this is a common problem often related to the choice of the correlation method and its associated hyperparameters. Methods like SparCC are specifically designed to handle compositional data and can reduce spurious correlations. The key hyperparameters to check include the number of inference iterations and the correlation threshold. Improper settings can lead to networks dominated by false positive relationships, misleading biological interpretation about cooperation or niche overlap [17] [18].

FAQ 2: How does the hyperparameter 'k' in the spring layout algorithm affect my network's interpretability?

The k hyperparameter in spring_layout controls the repulsive force between nodes. A value that is too low can cause excessive node overlap, making it impossible to distinguish key taxa, while a value that is too high can artificially stretch the network, breaking apart meaningful clusters.

Solution: Systematically increase k (e.g., from 0.1 to 2.0) and observe the network. A well-chosen k will clearly separate network modules, which often represent distinct ecological niches or functional groups [19].

FAQ 3: Why do my node labels appear misaligned in NetworkX visualizations?

This occurs when the pos (position) dictionary is not consistently applied to both the nodes and the labels.

Solution: Always compute the layout positions (e.g., pos = nx.spring_layout(G)) and pass this same pos dictionary to both nx.draw() and nx.draw_networkx_labels() to ensure perfect alignment [19].

FAQ 4: Should I use GridSearchCV or Bayesian Optimization for tuning my network inference model?

For high-dimensional hyperparameter spaces common in microbial inference (e.g., tuning multiple thresholds and method parameters), Bayesian Optimization is generally more efficient. It builds a probabilistic model to guide the search, unlike the brute-force approach of GridSearchCV. This is crucial when model training is computationally expensive [20].

FAQ 5: What does a loss of NaN (Not a Number) mean during hyperparameter optimization with Hyperopt? A loss of NaN typically indicates that your objective function returned an invalid number for a specific hyperparameter combination. This does not affect other runs but signals that certain hyperparameter values (e.g., an invalid regularization strength) lead to a numerically unstable model. Check the defined search space for invalid boundaries or consider adding checks in your objective function [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Overlapping Nodes and Unreadable Labels in Network Visualization

Problem: The network graph is a tangled mess where nodes cluster together, and labels are unreadable, preventing the identification of keystone taxa.

Diagnosis & Solution: This is primarily a layout and styling issue. Follow this systematic protocol to resolve it:

- Adjust Layout Repulsion: Increase the

khyperparameter innx.spring_layout(G, k=0.6)to add more space between nodes. Experiment with values between 0.1 and 2.0 [19]. - Scale Node Size by Importance: Instead of fixed sizes, scale nodes by their degree centrality to highlight hubs. This reduces visual clutter around less important nodes [19].

- Increase Figure Size: Provide more space for the graph to breathe using

plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))[19]. - Enhance Label Readability: Use a bold font with a contrasting color and add a white background to the labels.

Issue 2: Poor Prediction Accuracy in Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models

Problem: Your GNN model, designed to predict microbial temporal dynamics, shows low accuracy on the validation and test sets.

Diagnosis & Solution: This often stems from inappropriate model architecture or training hyperparameters, leading to overfitting on the training data.

- Validate Pre-clustering: For microbial time-series data, how you pre-cluster Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) before feeding them into the GNN is a critical hyperparameter. Clustering by graph network interaction strengths or ranked abundances has been shown to yield better prediction accuracy than clustering by biological function [22].

- Control Model Complexity: If using the

mc-predictionworkflow or a similar GNN, tune the complexity of the graph convolution and temporal convolution layers. Reduce the number of hidden units or layers if you have limited training samples to prevent overfitting [22]. - Leverage Transfer Learning: If your dataset is small, consider initializing your model with pre-trained weights from a larger, public microbial time-series dataset. This can significantly improve performance when data is scarce [23].

Issue 3: Microbial Network Lacks Modular Structure or Shows Unrealistic Connectivity

Problem: The inferred network is either too dense (a "hairball") or too sparse, and does not exhibit the expected modular (scale-free) topology often observed in microbial communities.

Diagnosis & Solution: The core issue lies in the hyperparameters of the network inference method itself.

- Tune the Correlation Threshold: This is a decisive hyperparameter. The table below summarizes the impact of different thresholds and the methods to choose them [17] [18].

- Select the Appropriate Correlation Metric: The choice of metric (e.g., Pearson, Spearman, SparCC) is a high-level hyperparameter. For compositional data (like relative abundances), use methods like SparCC or SPIEC-EASI that account for compositionality to avoid spurious connections [17] [23].

Table 1: Impact of Correlation Threshold on Network Structure

| Threshold | Network Density | Risk | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Low | High ("Hairball") | High False Positives | Inflated perception of species interactions and community complexity. |

| Too High | Low (Fragmented) | High False Negatives | Loss of true keystone taxa and critical ecological modules. |

| Optimal | Medium (Modular) | Balanced | Realistic representation of niche partitioning and functional groups. |

Optimal Threshold Selection Protocol:

- Random Matrix Theory (RMT): Use RMT to automatically determine a data-driven threshold, as implemented in tools like MENA. This is often more robust than arbitrary manual selection [18] [23].

- Stability-Based Selection: Perturb your data (e.g., via bootstrapping) and choose the threshold where the core network structure (e.g., number of modules, identified hubs) remains stable [17].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standardized Workflow for Microbial Network Inference and Validation

This protocol outlines the key steps for inferring a robust microbial co-occurrence network, highlighting critical hyperparameter choices () [17] [18].

Protocol 2: Hyperparameter Tuning for Network Inference Pipelines

This protocol uses a systematic approach to optimize the most sensitive hyperparameters in your inference pipeline [21] [20] [22].

Table 2: Hyperparameter Optimization Strategies

| Method | Best For | Key Hyperparameter to Tune | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GridSearchCV | Small, discrete search spaces (e.g., testing 3-4 threshold values). | Correlation threshold, p-value cutoff. | Computationally expensive; becomes infeasible with many parameters. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Larger, continuous search spaces (e.g., tuning multiple method parameters simultaneously). | SparCC iteration number, clustering resolution. | More efficient than grid search; learns from previous evaluations. |

| Manual Search | Initial exploration and leveraging deep domain knowledge. | Any, based on researcher intuition. | Inconsistent and hard to reproduce, but can be guided by biological plausibility. |

Step-by-Step Optimization with Bayesian Optimization:

- Define the Search Space: Specify the hyperparameters and their ranges (e.g.,

'correlation_threshold': (0.5, 0.9),'p_value': (0.01, 0.05)). - Define the Objective Function: This function should (a) build a network with the given hyperparameters, (b) calculate a loss metric (e.g., stability under bootstrapping, or deviation from an expected scale-free topology).

- Run the Optimizer: Use a library like

HyperoptorOptunato find the hyperparameters that minimize the loss. Note that the open-source version ofHyperoptis no longer maintained, andOptunaorRayTuneare recommended alternatives [21]. - Validate: Take the best hyperparameters and validate the resulting network's biological interpretability on a held-out dataset or through literature comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Tools for Microbial Network Inference and Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Critical Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|

| MicNet Toolbox [17] | An open-source Python toolbox for visualizing and analyzing microbial co-occurrence networks. | SparCC iteration count, UMAP dimensions, HDBSCAN clustering parameters. |

| SparCC [17] | Infers correlation networks from compositional (relative abundance) data. | Number of inference iterations, variance log-ratio threshold. |

| SPIEC-EASI [23] | Combines data transformation with sparse inverse covariance estimation to infer networks. | Method for sparsity (e.g., Meinshausen-Bühlmann vs Graphical Lasso), lambda (sparsity parameter). |

| NetworkX [19] | A Python library for the creation, manipulation, and study of complex networks. | k in spring_layout, node size, edge width, label font size. |

| GEDFN [23] | Graph Embedding Deep Feedforward Network for identifying microbial biomarkers. | Network embedding dimension, neural network layer size, learning rate. |

| mc-prediction [22] | A workflow using Graph Neural Networks to predict future microbial community dynamics. | Pre-clustering method, graph convolution layer size, temporal window length. |

| Graveobioside A | Graveobioside A, CAS:506410-53-3, MF:C26H28O15, MW:580.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Boc-D-Tyr-OH | Boc-D-Tyr-OH, CAS:3978-80-1; 70642-86-3, MF:C14H19NO5, MW:281.308 | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental properties of microbiome sequencing data that complicate analysis? Microbiome data from high-throughput sequencing is characterized by three primary properties that pose significant challenges for statistical and machine learning analysis [24]:

- Compositionality: The data represents relative abundances (proportions) rather than absolute counts. Since each sample is sequenced to a different depth (number of reads), the data is constrained to a constant sum (e.g., 1 or 100%). This means an increase in the relative abundance of one microbial taxon necessitates an apparent decrease in others, creating spurious correlations [24].

- High Dimensionality: The number of features (e.g., microbial taxa, genes) is vastly greater than the number of biological samples. This "curse of dimensionality" increases the risk of overfitting and complicates model generalization [24] [25].

- Sparsity: Microbial datasets contain a high number of zeros, representing taxa that are either truly absent or undetected due to technical limitations. This sparsity can skew distance metrics and statistical models [24] [25].

Q2: How does data compositionality impact machine learning-based biomarker discovery? Data compositionality significantly influences the feature importance and selection process in machine learning models. A 2025 study analyzing over 8,500 metagenomic samples found that while overall classification performance (e.g., distinguishing healthy from diseased) was robust to different data transformations, the specific microbial features identified as the most important varied dramatically depending on the transformation applied [26]. This means that biomarker lists generated by machine learning are not absolute and are highly dependent on how the compositional data was preprocessed, necessitating caution when interpreting results for network inference or therapeutic development [26].

Q3: My microbiome data is very sparse. Should I impute the zeros or use a presence-absence model? For classification tasks, using a presence-absence (PA) transformation is a robust and often high-performing strategy. Recent large-scale benchmarking has demonstrated that PA transformation performs comparably to, and sometimes even better than, more complex abundance-based transformations (like CLR or TSS) when predicting host phenotypes from microbiome data [26]. This approach completely bypasses the issue of dealing with zeros and compositionality for these specific tasks. For analyses requiring abundance information, compositional data transformations like CLR are generally preferred over imputation [24].

Q4: Which data visualization techniques are best for exploring my microbiome data? The choice of visualization depends entirely on the analytical question and whether you are examining samples individually or in groups [25].

- Alpha Diversity (within-sample diversity): Use boxplots for group-level comparisons and scatter plots for examining all samples [25].

- Beta Diversity (between-sample diversity): Use ordination plots (e.g., PCoA) for visualizing patterns among groups. For comparing individual samples, heatmaps or dendrograms are more effective [25].

- Taxonomic Distribution: Use bar charts or pie charts for group-level summaries. For all samples, a heatmap is more appropriate [25].

- Core Taxa: For comparing more than three groups, UpSet plots are strongly recommended over complex and hard-to-read Venn diagrams [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Machine Learning Classifier Performance

Problem: Your ML model for predicting a host phenotype (e.g., disease state) has low accuracy or fails to generalize.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unaddressed Compositionality | Check if your data preprocessing includes a compositionally-aware transformation. | Apply a Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation or use a Presence-Absence (PA) transformation, which has been shown to be highly effective for classification [24] [26]. |

| High Dimensionality & Overfitting | Evaluate the feature-to-sample ratio. Check performance on a held-out test set. | Implement strong regularization (e.g., Elastic Net) or use tree-based methods (e.g., Random Forest) that are more robust. Perform rigorous cross-validation [24]. |

| Confounding Technical Variation | Perform unconstrained ordination (e.g., NMDS). Check if samples cluster by batch, sequencing run, or DNA extraction kit. | Use batch effect correction methods like ComBat or RemoveBatchEffect to account for technical noise before model training [24]. |

| Ineffective Data Transformation | Benchmark multiple transformations with a simple model. | Test various transformations. Note that rCLR and ILR have been shown to underperform in some ML classification tasks [26]. |

Guide 2: Handling Challenges in Microbial Network Inference

Problem: Your inferred microbial network is unstable, difficult to interpret, or shows questionable ecological relationships.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Spurious Correlations from Compositionality | Network inference is based on raw relative abundance or TSS-normalized data. | Use compositionally-robust correlation methods such as SparCC or * proportionality* methods. Always transform data with CLR before calculating standard correlations [24]. |

| Hyperparameter Sensitivity | The network structure changes drastically with small changes in correlation threshold or sparsity parameters. | Perform stability selection or leverage data resampling (bootstrapping) to identify robust edges. Systematically evaluate a range of hyperparameters. |

| Excess of Zeros | A large proportion of taxa have a very low prevalence, inflating the number of zero-inflated correlations. | Apply a prevalence filter (e.g., retain taxa present in at least 10-20% of samples) before network inference to reduce noise [26]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Data Transformations for Classification

This protocol is adapted from a large-scale 2025 study on the effects of data transformation in microbiome ML [26].

Objective: To systematically evaluate the impact of different data transformations on the performance and feature selection of a machine learning classifier.

Materials:

- Microbial abundance table (OTU/ASV table from 16S rRNA sequencing or species table from metagenomics).

- Metadata with the target phenotype (e.g., healthy/diseased).

- Computational environment with R/Python and necessary libraries (e.g.,

scikit-learn,caret,randomForest,xgboost).

Workflow:

- Preprocessing: Filter the abundance table to remove very low-prevalence features (e.g., those present in <10% of samples).

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training (e.g., 70%) and a held-out test set (30%). Stratify the split based on the target phenotype.

- Apply Transformations: In the training set only, apply a suite of transformations to avoid data leakage.

- PA: Convert abundances to 1 (present) or 0 (absent).

- TSS: Divide each count by the total sample count.

- CLR:

log(abundance / geometric_mean(abundances)). Handle zeros with a multiplicative replacement. - aSIN:

arcsin(sqrt(relative_abundance)). - (Optional) Others:

ILR,ALR,log(TSS).

- Train Models: Train a standard classifier (e.g., Random Forest) on each transformed version of the training data.

- Evaluate Performance: Apply the same transformation-fitted models to the test set and compare performance using AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve).

- Analyze Features: Compare the top 20 most important features (e.g., from Random Forest's Gini importance) across the different transformations.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this benchmarking process:

Protocol 2: A Compositionally-Robust Workflow for Microbial Network Inference

Objective: To construct a microbial co-occurrence network that mitigates the effects of compositionality and sparsity.

Materials: As in Protocol 1.

Workflow:

- Preprocessing & Filtering: Aggressively filter the dataset to retain only taxa that meet a minimum prevalence and abundance threshold to reduce sparsity-induced noise.

- Compositional Transformation: Apply the CLR transformation to the entire filtered abundance table. This is a critical step to move data from the simplex to real space.

- Correlation Matrix Calculation: Calculate all pairwise correlations between the CLR-transformed microbial abundances. Standard Pearson or SparCC can be used at this stage.

- Hyperparameter Tuning (Sparsification): The primary hyperparameter in network inference is the threshold used to sparsify the correlation matrix into a network (adjacency matrix). Test different methods:

- Threshold-based: Retain only correlations with an absolute value above a defined cutoff (e.g., |r| > 0.3, 0.5, etc.).

- P-value-based: Retain only statistically significant correlations after multiple-testing correction.

- Stability-based: Use methods like

bootstrappingorBioEnvto select the threshold that yields the most stable network structure.

- Network Analysis & Visualization: Use network analysis tools (e.g.,

igraph,cytoscape) to calculate properties (modularity, centrality) and visualize the final network.

The logical relationship between data properties, corrective actions, and analysis goals is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Microbiome Data Analysis

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Use-Case | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| QIIME 2 [24] | End-to-End Pipeline | A powerful, extensible platform for processing raw sequencing data into abundance tables and conducting downstream statistical analyses. |

| CLR Transformation [24] [26] | Data Normalization | A compositional transformation that mitigates spurious correlations by log-transforming data relative to its geometric mean. Crucial for correlation-based network inference. |

| Presence-Absence (PA) Transformation [26] | Data Simplification for ML | Converts abundance data to binary (1/0). A robust and high-performing strategy for phenotype classification tasks that avoids compositionality and sparsity issues. |

| SparCC [24] | Network Inference | An algorithm specifically designed to infer correlation networks from compositional data, providing more accurate estimates of microbial associations. |

| Random Forest [24] [26] | Machine Learning | A versatile classification algorithm robust to high dimensionality and complex interactions, frequently used for predicting host phenotypes from microbiome data. |

| Calypso [24] | User-Friendly Analysis | A web-based tool that offers a comprehensive suite for microbiome data analysis, including statistics and visualization, suitable for users with limited coding experience. |

| MicrobiomeAnalyst [24] | Web-Based Toolbox | A user-friendly web application for comprehensive statistical, functional, and visual analysis of microbiome data. |

| Broussonetine A | Broussonetine A, MF:C19H29NO8, MW:399.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pdhk-IN-3 | Pdhk-IN-3, MF:C17H16N2O2, MW:280.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methods for Hyperparameter Tuning in Complex Study Designs

Novel Cross-Validation Frameworks for Hyperparameter Selection and Model Evaluation

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My microbial network inference algorithm is overfitting. How can I use cross-validation to select better hyperparameters?

- Problem: The inferred network structure is too specific to your training data and fails to generalize, often due to poorly chosen hyperparameters that control network sparsity (e.g., the regularization strength in LASSO) [27].

- Solution: Implement a nested cross-validation framework [28] [29].

- Inner Loop: Used for hyperparameter tuning. Your dataset is split into K-folds. For each unique set of hyperparameters, the model is trained on K-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold to assess performance. This process is repeated to identify the best-performing hyperparameters [30] [28].

- Outer Loop: Used for performance estimation. A separate set of K-folds is used, where each fold is held out as a test set once. The model is trained on the remaining data using the optimal hyperparameters from the inner loop and then evaluated on the test set [30] [28].

- Troubleshooting:

- High Variance in Performance: If the inner loop performance varies drastically across folds, consider using stratified k-fold to ensure balanced class distribution in each fold or increase the number of folds (e.g., k=10) for more reliable estimates [30] [29].

- Computational Cost: Nested CV is computationally intensive. For very large datasets, a simple holdout validation set might be sufficient, but for the typically smaller microbiome datasets, the robustness of nested CV is worth the cost [28].

FAQ 2: How do I validate a network inference model when I have data from multiple, distinct environmental niches (e.g., different body sites or soil types)?

- Problem: Training on one environment and testing on another leads to poor performance because microbial associations are context-dependent [31].

- Solution: Employ the Same-All Cross-validation (SAC) framework [31].

- "Same" Scenario: Train and test the model on data from the same environmental niche. This evaluates how well the algorithm captures associations within a homogeneous habitat [31].

- "All" Scenario: Train the model on a combined dataset from multiple niches and test on a held-out set from one of them. This tests the algorithm's ability to generalize across diverse environments [31].

- Troubleshooting:

- Poor "All" Scenario Performance: This indicates the model is failing to learn robust, cross-environment associations. Consider using specialized algorithms like

fuser, which is based on fused LASSO and can share information between niches while still preserving niche-specific network edges [31].

- Poor "All" Scenario Performance: This indicates the model is failing to learn robust, cross-environment associations. Consider using specialized algorithms like

FAQ 3: I keep getting overoptimistic performance estimates. What common pitfalls should I avoid?

- Problem: The estimated model performance during development does not match its performance on truly new data.

- Solution & Pitfalls to Avoid:

- Data Leakage: Ensure that data preprocessing steps (like normalization) are fit only on the training folds and then applied to the validation/test folds. Performing preprocessing on the entire dataset before splitting introduces bias [32] [29].

- Tuning to the Test Set: Your final holdout test set should be used only once for a final, unbiased evaluation. Repeatedly tweaking your model based on test set performance will cause the model to overfit to that specific test set [30].

- Non-representative Test Sets: If your test set is not representative of the overall population (e.g., due to hidden subclasses or batch effects), performance estimates will be biased. Use random partitioning and consider subject-wise splitting if you have repeated measures from the same individual [30] [29].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol for Nested Cross-Validation

Purpose: To provide an unbiased estimate of model generalization performance while performing hyperparameter tuning [28] [29].

Methodology:

- Partition Data: Split the entire dataset into K outer folds (e.g., K=5).

- Outer Loop: For each of the K outer folds: a. Designate the current fold as the outer test set. b. Use the remaining K-1 folds as the model development set. c. Inner Loop: Partition the model development set into L inner folds (e.g., L=5). d. For each candidate hyperparameter set: * Train the model on L-1 inner folds. * Evaluate performance on the held-out inner validation fold. e. Identify the hyperparameter set with the best average performance across all inner folds. f. Train a final model on the entire model development set using these optimal hyperparameters. g. Evaluate this final model on the held-out outer test set to get one performance estimate.

- Final Model: The K performance estimates from the outer loop are averaged to produce a robust generalization error. A final model can then be retrained on the entire dataset using the hyperparameters that yielded the best overall performance [28].

Protocol for Same-All Cross-Validation (SAC)

Purpose: To benchmark an algorithm's performance in predicting microbial associations within the same habitat and across different habitats [31].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Organize your microbiome data into distinct groups based on environmental niches (e.g., body sites, treatment groups, time points).

- Preprocessing: Apply log-transformation to OTU count data and subsample to ensure balanced group sizes [31].

- "Same" Scenario:

- For each environmental group, perform standard k-fold cross-validation.

- Train and test the model using data only from that specific group.

- The average performance across all groups and folds measures within-habitat prediction accuracy.

- "All" Scenario:

- Combine data from all environmental groups.

- Perform k-fold cross-validation, ensuring that each test fold contains a representative sample of all groups.

- The model is trained on a mixture of habitats and tested on a held-out mixture, measuring cross-habitat generalization.

The workflow for implementing these protocols is summarized in the following diagram:

Quantitative Data from Microbial Studies

Table 1: Characteristics of Public Microbiome Datasets Used in CV Studies [27] [31]

| Dataset | Samples | Taxa | Sparsity (%) | Use Case in CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMPv35 | 6,000 | 10,730 | 98.71 | Large-scale benchmark for SAC framework [31] |

| MovingPictures | 1,967 | 22,765 | 97.06 | Temporal dynamics analysis [31] |

| TwinsUK | 1,024 | 8,480 | 87.70 | Disentangling genetic vs. environmental effects [31] |

| Baxter_CRC | 490 | 117 | 27.78 | Method comparison for network inference [27] |

| amgut2 | 296 | 138 | 34.60 | Method comparison for network inference [27] |

Table 2: Performance of Network Inference Algorithms in SAC Framework (Illustrative) [31]

| Algorithm | "Same" Scenario(Test Error) | "All" Scenario(Test Error) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| glmnet (Standard LASSO) | Baseline | Higher than "Same" | Infers a single generalized network [31] |

fuser (Fused LASSO) |

Comparable to glmnet | Lower than glmnet | Generates distinct, environment-specific networks [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Microbial Network Inference & Validation

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Co-occurrence Inference Algorithms | Statistical methods to infer microbial association networks from abundance data. | SPIEC-EASI [27], SparCC [27], glmnet [27] [31], fuser [31] |

| Cross-Validation Frameworks | Resampling methods for robust hyperparameter tuning and model evaluation. | Nested CV [28] [29], Same-All CV (SAC) [31], K-Fold [30] |

| Preprocessing Pipelines | Steps to clean and transform raw sequencing data for analysis. | Log-transformation (log10(x+1)) [31], low-prevalence OTU filtering [31], subsampling for group balance [31] |

| Public Microbiome Data Repositories | Sources of validated, high-throughput sequencing data for method development and testing. | Human Microbiome Project (HMP) [31], phyloseq datasets [27], MIMIC-III (for clinical correlations) [28] [29] |

| Resolvin D5 | Resolvin D5, MF:C22H32O4, MW:360.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Akr1C3-IN-13 | Akr1C3-IN-13, MF:C26H21NO4, MW:411.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementing the Same-All Cross-Validation (SAC) for Multi-Environment Data

Foundational Concepts of SAC

What is Same-All Cross-Validation (SAC) and why is it used in microbial network inference?

Same-All Cross-Validation (SAC) is a specialized validation framework designed to rigorously evaluate how well microbiome co-occurrence network inference algorithms perform across diverse environmental niches. It addresses a critical limitation in conventional methods that often analyze microbial associations within a single environment or combine data from different niches without preserving ecological distinctions [33].

SAC provides a principled, data-driven toolbox for tracking how microbial interaction networks shift across space and time, enabling more reliable forecasts of microbiome community responses to environmental change. This is particularly valuable for hyperparameter selection in models that aim to capture environment-specific network structures while sharing relevant information across habitats [33].

How does SAC differ from traditional cross-validation approaches?

Unlike traditional k-fold cross-validation that randomly splits data, SAC explicitly evaluates algorithm performance in two distinct prediction scenarios [33] [34]:

| Validation Scenario | Training Data | Testing Data | Evaluation Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Same" | Single environmental niche | Same environmental niche | Within-habitat predictive accuracy |

| "All" | Combined multiple environments | Combined multiple environments | Cross-habitat generalization ability |

This two-regime protocol provides the first rigorous benchmark for assessing how well co-occurrence network algorithms generalize across environmental niches, addressing a significant gap in microbial ecology research [33].

Implementation Guide

What are the key steps in implementing SAC for microbiome data?

Data Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Apply log transformation: Use log10(x + 1) to raw OTU count data to stabilize variance across abundance levels [33]

- Standardize group sizes: Calculate mean group size and randomly subsample equal numbers from each group to prevent imbalances [33]

- Remove low-prevalence OTUs: Reduce sparsity and potential noise in downstream models [33]

- Ensure equal samples: Final datasets should contain equal numbers of samples per experimental group with log-transformed abundances [33]

SAC Experimental Protocol:

- Define environmental groups: Identify distinct spatial or temporal niches in your microbiome data (e.g., different body sites, soil types, or sampling timepoints) [33]

- Implement "Same" scenario: For each environmental group, perform traditional k-fold cross-validation where training and testing occur within the same group [33]

- Implement "All" scenario: Combine data from all environmental groups, then perform k-fold cross-validation across the entire pooled dataset [33]

- Compare performance: Evaluate how algorithm performance differs between the two scenarios, with optimal methods showing robust performance in both regimes [33]

Which algorithms are most suitable for SAC framework?

The fuser algorithm, which implements fused lasso, is particularly well-suited for SAC as it retains subsample-specific signals while sharing relevant information across environments during training [33]. Unlike standard approaches that infer a single generalized network from combined data, fuser generates distinct, environment-specific predictive networks [33].

Traditional algorithms like glmnet can be used as baselines for comparison. Research shows fuser achieves comparable performance to glmnet in homogeneous environments ("Same" scenario) while significantly reducing test error in cross-environment ("All") predictions [33].

Troubleshooting Common SAC Implementation Issues

How should I handle high sparsity in microbiome data during SAC implementation?

Microbiome data typically exhibits high sparsity (often 85-99%), which poses challenges for network inference [33]. The recommended approach includes:

- Aggressive filtering: Remove low-prevalence OTUs to reduce sparsity and noise

- Appropriate transformations: Log10(x + 1) transformation helps stabilize variance while preserving zero values

- Regularization: Use algorithms with built-in regularization like fuser or glmnet to handle sparse data structures [33]

What should I do when my model shows good "Same" performance but poor "All" performance?

This performance discrepancy indicates your model may be overfitting to environment-specific signals without capturing generalizable patterns. Consider these solutions:

- Adjust hyperparameters: Increase regularization strength to encourage information sharing across environments

- Feature engineering: Identify and focus on microbial taxa that show consistent patterns across multiple environments

- Algorithm selection: Implement the fuser algorithm, which is specifically designed to balance environment-specific and shared signals [33]

How can I validate that my SAC implementation is working correctly?

- Benchmark against baselines: Compare your results with standard algorithms like glmnet to ensure expected performance patterns [33]

- Check group separation: Verify that environmental groups show distinct microbial association patterns

- Evaluate both regimes: Ensure you're properly calculating performance metrics for both "Same" and "All" scenarios separately

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools for SAC Implementation:

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in SAC Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Languages | R, Python | Core implementation and statistical analysis |

| Network Inference Algorithms | fuser, glmnet | Microbial association network estimation |

| Cross-Validation Frameworks | scikit-learn [34], custom SAC | Model validation and hyperparameter tuning |

| Microbiome Analysis | QIIME2 [35], PICRUSt2 [35] | Data preprocessing and functional profiling |

| Visualization | ggplot2, Graphviz | Results communication and workflow diagrams |

| Endoxifen (Z-isomer) | Endoxifen (Z-isomer), MF:C26H31NO2, MW:389.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ahx-DM1 | Ahx-DM1, MF:C38H55ClN4O10, MW:763.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Statistical Metrics for SAC Evaluation:

| Metric | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ELPD (Expected Log Predictive Density) | Overall predictive accuracy assessment [36] [37] | Model comparison |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | Absolute prediction error magnitude | Algorithm performance |

| R² (Explained Variance) | Proportion of variance explained | Model goodness-of-fit |

| Test Error Reduction | Improvement over baseline methods | "All" scenario performance |

Implementation Considerations for Microbial Data:

- Taxon-specific regularization: Different microbial taxa may require different regularization strengths based on their ecological roles [33]

- Multi-algorithm analysis: Complement fused approaches with standard algorithms to capture different aspects of microbial interactions [33]

- Spatio-temporal dynamics: Ensure your environmental groupings accurately reflect meaningful ecological distinctions [33]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using Fused Lasso over standard LASSO for my multi-environment microbiome study?

Standard LASSO estimates networks for each environment independently, which can lead to unstable results and an inability to systematically compare networks across environments. The Fused Lasso (fuser) addresses this by jointly estimating networks across multiple groups or environments. It introduces an additional penalty on the differences between corresponding coefficients (e.g., edge weights) across the networks. This approach leverages shared structures to improve the stability of each individual network estimate, making it particularly powerful for detecting consistent core interactions versus environment-specific variations [38].

Q2: My dataset has different sample sizes for each experimental group. How does Fused Lasso handle this?

The Fused Graphical Lasso (FGL) method, a common implementation of the Fused Lasso for network inference, is designed to handle this common scenario. It can be applied to datasets where different groups (e.g., healthy vs. diseased cohorts, different soil types) have different numbers of samples. The algorithm works by jointly estimating the precision matrices (inverse covariance matrices) across all groups, effectively pooling information to improve each estimate without requiring balanced sample sizes [38].

Q3: During hyperparameter tuning, what is the practical difference between the lasso (λ1) and fusion (λ2) penalties?

The two hyperparameters control distinct aspects of the model:

- Lasso Penalty (λ1): This penalty promotes sparsity within each individual network. A higher value for λ1 will result in networks with fewer edges (more zero coefficients), simplifying the model and focusing on the strongest associations [39] [40].

- Fusion Penalty (λ2): This penalty promotes similarity between the networks of different groups. A higher value for λ2 encourages corresponding edges across networks to have identical weights. When λ2 is sufficiently high, the networks become identical, effectively merging the groups. A lower λ2 allows for more differences between the group-specific networks [38].

Q4: I'm getting inconsistent network structures when I rerun the analysis on bootstrapped samples of my data. How can I improve stability?

Inconsistency can arise from high correlation between microbial taxa or small sample sizes. To improve stability:

- Standardize your data: Ensure all microbial abundance features are standardized to zero mean and unit variance before analysis. This prevents the penalty from being unfairly applied to features on larger scales [39].

- Use the "one-standard-error" rule: During cross-validation, instead of selecting the hyperparameters (λ1, λ2) that give the absolute minimum error, choose the most parsimonious model (highest λ values) whose error is within one standard error of the minimum. This selects a simpler, more stable model [39].

- Consider the Elastic Net: If the instability is primarily due to highly correlated taxa, using an Elastic Net penalty (which combines Lasso and Ridge regression) within the Fused Lasso framework can help. Ridge regression shrinks coefficients of correlated variables together, rather than arbitrarily selecting one [39] [40].

Q5: Are there specific R packages available to implement Fused Lasso for network inference?