PLFA Analysis: A Powerful Biomarker Technique for Microbial Community Profiling in Biomedical and Environmental Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) analysis, a key biomarker technique for profiling viable microbial communities.

PLFA Analysis: A Powerful Biomarker Technique for Microbial Community Profiling in Biomedical and Environmental Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) analysis, a key biomarker technique for profiling viable microbial communities. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of PLFA, detailing its application in assessing microbial biomass, community structure, and stress responses across diverse environments from soils to wastewater treatment systems. The content delivers a practical guide to methodological protocols, troubleshooting common issues, and data interpretation. Furthermore, it offers a critical validation of PLFA by comparing its performance, advantages, and limitations against other prevalent molecular methods like qPCR, ddPCR, and 16S rRNA gene metabarcoding, empowering professionals to select the most appropriate tool for their research objectives.

What is PLFA Analysis? Unlocking the Microbial Biomarker in Cell Membranes

Phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) have become a cornerstone technique in microbial ecology for quantifying viable microbial biomass and assessing broad-scale community composition. This method leverages the chemical properties of phospholipids, which are essential components of all cellular membranes. A critical principle underpinning PLFA analysis is that upon cell death, phospholipids are rapidly degraded to neutral lipids; consequently, the detection of phospholipids serves as a reliable indicator of living microbial biomass at the time of sampling [1]. This technical note details the core principles, standard protocols, and key applications of PLFA analysis for researchers in microbial community profiling.

The utility of PLFA profiling extends beyond a simple biomass estimate. Because certain fatty acids are more predominant in specific microbial groups, the analysis of PLFA patterns can be used to trace shifts in the functional composition of the microbial community, such as the ratio of fungi to bacteria or Gram-positive to Gram-negative bacteria [2]. This method provides a valuable balance of cost-effectiveness, reliability, and functional insight, complementing modern genomic techniques like DNA metabarcoding [1].

Core Principles and Key Biomarkers

The Link Between PLFAs and Living Biomass

The validity of PLFAs as indicators of living microbial biomass rests on two well-established biochemical facts:

- Integral Membrane Components: Phospholipids are the primary building blocks of microbial cell membranes and are indispensable for maintaining cell integrity and function [3].

- Rapid Post-Mortem Degradation: Following cell death, phospholipids are quickly hydrolyzed by cellular and environmental enzymes. This rapid degradation means that the extracted PLFA profile represents a "snapshot" of the living community, avoiding the inclusion of non-viable cells [1] [3].

Microbial Group-Specific Biomarker PLFAs

While few fatty acids are exclusive to a single taxon, specific PLFAs and their ratios are consistently associated with broad microbial functional groups. The following table summarizes key biomarker PLFAs used in ecological studies.

Table 1: Common PLFA Biomarkers for Major Microbial Groups

| Microbial Group | Key Biomarker PLFAs | Notes and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Total Bacteria | 14:0, 15:0, 16:0, 17:0, 18:0, 16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c, cy17:0, cy19:0 [3] | Saturated, branched, and cyclopropyl fatty acids are common. |

| Gram-Positive Bacteria | iso-15:0, anteiso-15:0, iso-16:0, iso-17:0, anteiso-17:0 [3] | Characterized by terminally branched fatty acids. |

| Gram-Negative Bacteria | 16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c, cy17:0, cy19:0, 3-OH 10:0 [3] | Characterized by monoenoic and cyclopropyl fatty acids. |

| General Fungi | 18:1ω9c, 18:2ω6c [2] [3] | Polyunsaturated fatty acids are less common in bacteria. |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi | 16:1ω5c [3] | A key biomarker for this specific fungal group. |

| Actinomycetes | 10-Me 16:0, 10-Me 17:0, 10-Me 18:0 [3] | 10-methyl branched fatty acids are typical. |

| Anaerobic Bacteria | cy17:0, cy19:0 [3] | Cyclopropyl fatty acids can also indicate older Gram-negative cells. |

Detailed Standard Protocol for PLFA Analysis

The following protocol, adapted from standardized methods, outlines the major steps for PLFA extraction and analysis from soil samples [2]. Key considerations for method optimization from recent research are integrated into the steps.

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

- Collection & Sieving: Collect soil samples using sterile tools. Transport on ice and store at -80°C until processing. Homogenize samples by sieving (e.g., 2 mm mesh) to remove stones and root fragments [2].

- Freeze-Drying & Grinding: Freeze-dry the sieved soils to remove water. Grind the freeze-dried soil to a fine, flour-like consistency using a ball mill or mortar and pestle to ensure homogeneity [2].

- Lipid Extraction (Bligh & Dyer Method):

- Weigh the freeze-dried soil (0.5-5 g, depending on organic matter content) into a glass centrifuge tube.

- In a fume hood, add a single-phase extraction mixture of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), chloroform, and methanol in a specific volume ratio (e.g., 0.8:1:2, P-buffer:CHCl₃:MeOH) [2].

- Cap tubes tightly and shake horizontally for 1-2 hours.

- Centrifuge to separate phases and collect the organic (chloroform) layer containing the lipids.

Lipid Fractionation by Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

- Column Preparation: Pack silica gel into SPE columns or use commercial cartridges.

- Sample Loading: Transfer the lipid-containing chloroform extract onto the silica column. The silica gel will bind the lipids based on their polarity.

- Sequential Elution: Fractionate the lipids by eluting with a series of solvents of increasing polarity [2]:

- Chloroform: Elutes neutral lipids (e.g., triglycerides, free fatty acids).

- Acetone: Elutes glycolipids.

- Methanol: Elutes the target phospholipids.

Critical Methodological Note: Recent studies highlight that this fractionation can be imperfect. A non-negligible proportion of phospholipids may be lost in the chloroform fraction, while some glycolipids may be eluted with methanol, potentially biasing results. Researchers are advised to validate their elution efficiency [4].

Transesterification to Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs)

- The methanol fraction containing phospholipids is evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen gas.

- Alkaline Methanolysis is the most common derivatization method. Add a mild methanolic potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution to the dried phospholipids.

- Incubate at a moderate temperature (e.g., 37°C for 30 minutes) to convert phospholipid fatty acids into less polar Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs), which are volatile enough for gas chromatography (GC) analysis [2]. Acid-catalyzed methylation is an alternative but requires longer reaction times [4].

Analysis by Gas Chromatography (GC)

- Extraction & Concentration: After methylation, stop the reaction and extract the FAMEs into an organic solvent (e.g., hexane-methylene tert-butyl ether mixture). Concentrate the extract under nitrogen.

- GC Injection & Separation: Inject the FAME extract into a Gas Chromatograph equipped with a capillary column. The FAMEs are separated based on their chain length, degree of saturation, and other structural features as they travel through the column.

- Detection & Identification: A Flame Ionization Detector (FID) or Mass Spectrometer (MS) is used to detect the eluting FAMEs. Peaks are identified by comparing their retention times to those of known FAME standards.

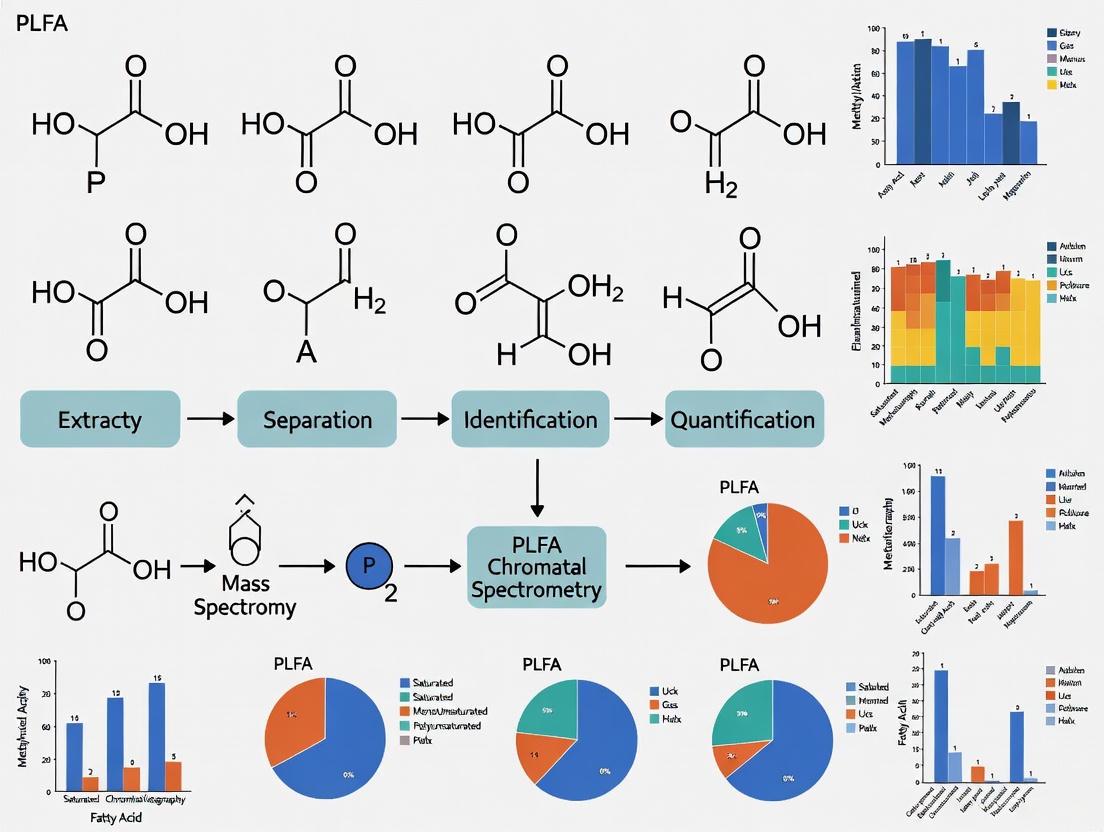

The workflow below summarizes the key steps in the PLFA analysis protocol.

Figure 1: PLFA Analysis Workflow from Sample to Data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful PLFA analysis requires specific, high-purity reagents and materials. The following table details the essential components of the toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for PLFA Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform (HPLC grade) | Organic solvent for lipid extraction. | Part of the Bligh & Dyer mixture. Handle with appropriate PPE in a fume hood [2]. |

| Methanol (HPLC grade) | Organic solvent for lipid extraction and elution. | Used in extraction and as the polar eluent for phospholipids in SPE [2]. |

| Phosphate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0) | Aqueous component of extraction mixture. | Helps maintain pH and improves contact between solvent and cells [2]. |

| Silica Gel Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Fractionation of lipid classes by polarity. | Critical for isolating phospholipids from neutral lipids and glycolipids [2]. |

| Methanolic KOH Solution | Alkaline catalyst for transesterification. | Converts phospholipids to FAMEs under mild conditions [2]. |

| FAME Standards (e.g., 19:0 EE) | Internal standard for GC quantification. | Added before extraction to correct for losses during the procedure [2]. |

| Hexane/MTBE Mixture | Solvent for extracting FAMEs post-derivatization. | Used to transfer the FAMEs into a solvent compatible with GC injection [2]. |

| C15H22ClNS | C15H22ClNS Research Chemical | High-purity C15H22ClNS for laboratory research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary diagnostics. |

| C16H19N3O6S3 | C16H19N3O6S3, MF:C16H19N3O6S3, MW:445.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Considerations and Recent Insights

While the standard protocol is robust, researchers should be aware of ongoing methodological refinements:

- Extraction Efficiency: The choice between acidic (e.g., citrate) and alkaline (e.g., phosphate) buffers can affect extraction yield depending on soil pH. Recent studies using lipid standards suggest citrate buffer may perform better in acidic soils [4].

- Chromatographic Separation: The classical sequential elution with chloroform, acetone, and methanol may not perfectly separate lipid classes. Significant proportions of phospholipids can be lost in the chloroform fraction, while glycolipids can contaminate the methanol fraction, leading to potential bias in biomass estimates [4].

- Catalyst Choice: Alkaline catalysts (e.g., KOH) are generally more efficient for transesterification than acidic catalysts (e.g., HCl), resulting in higher mean recovery rates of PLFAs (86% vs. 67%) [4].

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis serves as a crucial chemotaxonomic method in microbial ecology for profiling living microbial communities in environmental samples. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to the standardized nomenclature and interpretation of fatty acid signatures, enabling researchers to accurately assess microbial biomass, community structure, and physiological stress responses. We detail established protocols for high-throughput PLFA extraction and analysis, present structured frameworks for biomarker interpretation, and visualize critical workflow relationships. The guidance presented herein supports the broader thesis that PLFA profiling, when properly executed and interpreted, provides reliable insights into microbial community dynamics that complement molecular approaches, thereby offering a valuable tool for researchers investigating microbial responses to environmental perturbations, bioremediation potential, and ecosystem functioning.

Phospholipid-derived fatty acids (PLFAs) are essential components of microbial cell membranes and have emerged as powerful chemotaxonomic markers for studying microbial communities in diverse environments including soils, sediments, and water systems [5]. The fundamental premise of PLFA analysis lies in the rapid degradation of phospholipids following cell death, meaning detected PLFAs primarily represent living microorganisms at the time of sampling [5] [6]. This technique provides a snapshot of the viable microbial community, offering advantages over culture-dependent methods that often yield biased results due to the differential cultivability of microorganisms [5].

PLFA profiling enables simultaneous assessment of microbial biomass, community structure, and physiological status through the identification of specific fatty acid signatures that serve as biomarkers for broad taxonomic groups [6] [7]. When combined with stable isotope probing (SIP), PLFA analysis can further identify metabolically active populations within complex communities [5]. Despite limitations in taxonomic resolution compared to DNA-based methods, PLFA analysis remains a valuable independent approach for characterizing dominant microbial groups and their functional responses to environmental changes [8] [1].

PLFA Nomenclature and Biochemical Significance

Standard Nomenclature System

The PLFA naming system follows a standardized format that conveys essential structural information about each fatty acid molecule. Understanding this nomenclature is fundamental to accurate biomarker interpretation.

The basic format is A:BωC(X), where:

Arepresents the total number of carbon atomsBindicates the number of double bondsCspecifies the position of the first double bond from the methyl end (ω) of the moleculeXdenotes additional structural features (e.g., branching, cyclization)

For example, 16:1ω7c describes a 16-carbon fatty acid with one double bond located between the 7th and 8th carbons from the methyl end, with cis configuration.

Structural Modifications and Taxonomic Implications

Specific structural modifications to the fatty acid chain provide valuable taxonomic information:

- Branched PLFAs: Include iso (methyl branch at penultimate carbon) and anteiso (methyl branch at antepenultimate carbon) configurations, primarily associated with Gram-positive bacteria (except Actinobacteria) [5] [8].

- Monounsaturated PLFAs: Characterized by one double bond, with specific positional isomers indicating different microbial groups. The omega (ω) designation indicates the position of the double bond from the methyl end [5].

- Polyunsaturated PLFAs: Contain multiple double bonds and are typically associated with eukaryotic microorganisms including fungi, algae, and protozoa, though they are generally absent in bacteria [5].

- Cyclopropane PLFAs: Formed by methylation of unsaturated fatty acids in Gram-negative bacteria under conditions of physiological stress or stationary phase [5].

- 10-methyl branched PLFAs: Specific to Actinobacteria (formerly actinomycetes), characterized by a methyl branch at the 10th carbon position [5].

Microbial Biomarkers and Taxonomic Assignments

Table 1: Standard PLFA Biomarkers for Major Microbial Groups

| Microbial Group | Key Biomarker PLFAs | Specific Examples | Notes and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Biomass | Total PLFA | All detected PLFAs | Measure of viable microbial biomass [5] |

| Gram-positive Bacteria | iso- and anteiso-branched | 15:0 iso, 15:0 anteiso, 17:0 iso | Excludes Actinobacteria; Firmicutes phylum [5] [8] |

| Gram-negative Bacteria | Monounsaturated, cyclopropane | 16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c, 19:0 cyclo ω7c | Cyclopropane indicates stress [5] |

| Actinobacteria | 10-methyl branched | 16:0 10-methyl, 18:0 10-methyl | Previously called actinomycetes [5] [8] |

| General Fungi | Polyunsaturated | 18:2ω6,9 | Saprotrophic fungi; use ergosterol for specificity [8] |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) | Monounsaturated | 16:1ω5 | Specific for AMF hyphae [5] [8] |

| Anaerobic Bacteria | Dimethyl acetals | 16:0 DMA | Formed during derivatization [5] |

| Methane-Oxidizing Bacteria | Specific monounsaturated | 16:1ω8c (Type I), 18:1ω8c (Type II) | Specialized functional group [5] |

Interpreting Diagnostic Ratios and Stress Indicators

Beyond specific biomarkers, several PLFA ratios provide insights into microbial community dynamics and physiological status:

- Fungal-to-Bacterial Ratio (F/B): Calculated as fungal PLFA (18:2ω6,9) to bacterial PLFA (sum of Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and actinobacterial biomarkers). Higher ratios suggest fungal-dominated decomposition pathways and may indicate reduced disturbance [6] [7].

- Gram-positive to Gram-negative Ratio (GP/GN): Increased ratios may indicate microbial starvation or response to heavy metal toxicity [6].

- Gram-negative Stress Ratio: Calculated as (cy17:0 + cy19:0)/(16:1ω7c + 18:1ω7c). Values >0.1 indicate physiological stress due to nutrient limitation, toxic compounds, or other environmental challenges [6].

- Saturated-to-Unsaturated Ratio: Shifts in this ratio may reflect microbial adaptation to temperature changes or other membrane-fluidizing conditions [6].

Table 2: PLFA-Based Ratios for Assessing Microbial Community Status

| Ratio | Calculation | Ecological Interpretation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal:Bacterial (F/B) | Fungal PLFA / Bacterial PLFA | Higher values in less disturbed systems; indicates decomposition pathways | Use specific biomarkers; 18:2ω6,9 for fungi [6] |

| Gram-positive:Gram-negative (GP/GN) | G+ PLFA / G- PLFA | Increase indicates starvation or heavy metal toxicity [6] | Exclude Actinobacteria from G+ for Firmicutes [8] |

| Gram-negative Stress | (cy17:0 + cy19:0) / (16:1ω7c + 18:1ω7c) | >0.1 indicates physiological stress [6] | Useful for assessing nutrient limitation, toxic conditions |

| Cyclopropane:Precursor | cy19:0 / 18:1ω7c | Indicator of slowing growth/stationary phase in G- bacteria [5] | Reflects nutritional status |

| Total PLFA | Sum of all PLFAs | Microbial biomass indicator [8] | Correlates with microbial biomass C |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Throughput PLFA Extraction Protocol

The following protocol adapts the high-throughput method described by Buyer and Sasser (2012) enabling processing of 96 samples in 1.5 days, representing a 4-5 fold increase in efficiency over traditional methods [9].

Materials Required:

- Solvents: Chloroform, methanol, phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Equipment: Centrifugal evaporator, 96-well solid phase extraction (SPE) plates, glass vials in 96-well format, gas chromatograph with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) or mass spectrometer (GC-MS)

- Standards: Internal standard (e.g., 19:0 phosphatidylcholine), FAME standards for calibration

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dispense 0.5-2.0 g of freeze-dried soil into glass test tubes.

- Lipid Extraction: Perform modified Bligh-Dyer extraction using chloroform:methanol:phosphate buffer (1:2:0.8 v/v/v) with brief sonication followed by shaking for 2 hours [5] [9].

- Phase Separation: Add additional chloroform and water to separate phases; collect the lipid-containing chloroform layer.

- Fractionation: Load extracts onto 96-well SPE plates; elute neutral lipids, glycolipids, and phospholipids sequentially with solvents of increasing polarity.

- Phospholipid Collection: Collect phospholipid fraction in glass vials.

- Transesterification: Convert phospholipids to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) using mild alkaline methanolysis.

- Analysis: Analyze FAMEs by GC-FID or GC-MS with appropriate calibration standards [5] [9].

Quality Control:

- Include internal standards in all samples to correct for extraction efficiency [10].

- Use blank extracts to monitor contamination.

- Analyze standard reference mixtures to verify chromatographic performance.

Data Processing and Normalization

Modern PLFA analysis utilizes specialized software (e.g., Sherlock Microbial Identification System) for peak identification and quantification [5]. Key considerations include:

- Scaling Factor: Apply recovery correction based on internal standard response [10].

- Peak Identification: Identify FAMEs by comparing retention times to commercial standards.

- Data Reporting: Express results as nmol PLFA per g dry weight of sample.

Figure 1: PLFA Analysis Workflow from Sample Collection to Data Interpretation

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for PLFA Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform-Methanol Mixture | Lipid extraction from samples | Bligh-Dyer solvent system [5] [9] |

| Phosphate Buffer | Maintain pH during extraction | Typically 0.05 M, pH 7.4 [5] |

| Internal Standard | Correction for extraction efficiency | Non-native PLFA (e.g., 19:0 phosphatidylcholine) [10] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Columns | Lipid fractionation | 96-well format for high throughput [9] |

| Methanolic NaOH/KOH | Transesterification to FAMEs | Mild alkaline conditions prevent degradation [5] |

| FAME Standards | Peak identification and calibration | Commercial mixtures for retention time alignment [5] |

| Gas Chromatograph | Separation and detection of FAMEs | GC-FID for quantification; GC-MS for verification [5] |

| Capillary GC Column | Separation of FAMEs | Polar stationary phase (e.g., cyanopropyl) [5] |

| Centrifugal Evaporator | Solvent removal | Enables high-throughput processing [9] |

| C29H25Cl2NO4 | C29H25Cl2NO4|High-Purity Reference Standard | |

| C17H13N5OS3 | C17H13N5OS3 | High-purity C17H13N5OS3 for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. |

Applications and Case Studies

Monitoring Microbial Community Shifts in Disturbed Ecosystems

PLFA profiling effectively detects microbial community changes following environmental disturbances. A study of forest clearcutting demonstrated that microbial biomass (total PLFA) and specific bacterial and fungal biomarkers were significantly reduced in 8-year-old clearcuts compared to old-growth forests [11]. After 25 years, microbial communities showed substantial recovery, approaching the composition of old-growth forests, highlighting the resilience of soil microbial communities [11]. The study also revealed that seasonal temporal changes exerted greater influence on PLFA profiles than stand age differences, emphasizing the importance of considering temporal variation in study design [11].

Assessing Heavy Metal Impact on Soil Microbes

Research on municipal solid waste contamination demonstrated PLFA's sensitivity to heavy metal stress [6]. The investigation found negative correlations between heavy metal concentrations (particularly Zn and Cd) and most microbial biomarkers [6]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) biomass, indicated by 16:1ω5, showed positive correlation with other microbial groups and total PLFA, suggesting its potential role in ecosystem recovery [6]. Stress indicators including the Gram-negative stress ratio effectively reflected the physiological impact of heavy metal contamination on soil microbial communities [6].

Figure 2: PLFA Biomarker Applications in Microbial Ecology Research

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

While PLFA analysis provides valuable insights into microbial community structure, researchers must acknowledge several important limitations:

- Specificity Constraints: Many PLFA biomarkers are not exclusive to single microbial taxa, potentially occurring across multiple groups [5] [8]. Straight-chain PLFAs (14:0, 15:0, 16:0, 17:0) occur in all microorganisms, not exclusively in bacteria as sometimes misassigned [8].

- Recycling Effects: PLFA recycling during decomposition may introduce inaccuracies in community assessment, though the extent remains poorly quantified [8].

- Extraction Efficiency: Variations in extraction efficiency across soil types require internal standardization and potential protocol adjustments [10] [9].

- Archaeal Exclusion: Standard PLFA protocols target ester-linked phospholipids, missing archaea whose membranes contain ether-linked lipids [5].

- Interpretation Consistency: Discrepancies in PLFA interpretation between studies necessitate careful standardization and potentially multivariate statistical approaches [6] [7].

To address these limitations, researchers should:

- Implement multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., PCA) to identify patterns across multiple PLFAs rather than relying on individual biomarkers [6].

- Combine PLFA with complementary methods (e.g., DNA analysis, ergosterol measurement) for fungal assessment [8].

- Clearly document biomarker assignment decisions and acknowledge limitations in interpretation.

- Participate in community efforts to standardize practices, such as the global PLFA database initiative [1].

PLFA analysis remains a powerful, cost-effective approach for profiling living microbial communities when practitioners employ standardized nomenclature, recognize biomarker limitations, and implement appropriate methodological controls. The technique provides unique insights into microbial biomass, community structure, and physiological status that complement nucleic acid-based methods. As microbial ecology continues to address pressing environmental challenges, from climate change to ecosystem restoration, proper application and interpretation of PLFA signatures will remain an essential component in the microbial ecologist's toolkit. Future methodological developments should focus on refining biomarker specificity, enhancing extraction efficiency across diverse sample types, and integrating PLFA data with other microbial community assessment techniques within unified analytical frameworks.

Key Microbial Groups and Their Characteristic PLFA Biomarkers

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis is a widely established method for quantifying viable microbial biomass and assessing the broad structure of microbial communities in environmental samples. This technique is grounded in the principle that specific phospholipids, which are integral components of living cell membranes and are rapidly degraded upon cell death, can serve as biomarkers for different microbial groups [1] [4]. The ability to profile these biomarkers provides researchers with a quantitative snapshot of the living microbial community, offering insights into its size and composition without the need for cultivation [6]. This application note details the key microbial groups, their characteristic PLFA biomarkers, and standardized protocols for their analysis, providing a essential resource for research in microbial ecology.

Key Microbial Groups and Their Biomarkers

The following table summarizes the primary microbial groups and their most characteristic PLFA biomarkers as identified in recent scientific literature.

Table 1: Characteristic PLFA Biomarkers for Key Microbial Groups

| Microbial Group | Characteristic PLFA Biomarkers | Specific Examples (where provided) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Bacteria | Mono-unsaturated, cyclopropyl, and saturated branched fatty acids [6] [12] | |

| Gram-Negative Bacteria | Mono-unsaturated fatty acids and cyclopropyl fatty acids [13] [6] | 16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c, cy17:0, cy19:0 [6] |

| Gram-Positive Bacteria | iso and anteiso saturated branched fatty acids [13] [6] | i15:0, a15:0, i16:0, a17:0 [14] [13] |

| General Fungi | Poly-unsaturated fatty acids and specific mono-unsaturates [6] [12] | 18:2ω6,9 [6], 18:1ω9c [14] |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) | Specific mono-unsaturated fatty acids [13] [6] | 16:1ω5c [13] [6] |

| Actinomycetes | Mid-chain branched fatty acids with a methyl group [14] [6] | 10-methyl 16:0, 10-methyl 17:0 (17:0 10Me), 10-methyl 18:0 (18:0 10Me) [14] [15] |

| Protozoa | Poly-unsaturated fatty acids [14] | 20:4ω6,9,12,15c [14] |

| Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria | Specific branched and saturated fatty acids [14] | 16:0 10Me [14] |

These biomarkers enable the calculation of informative ecological ratios. The fungi-to-bacteria (F/B) ratio is a common metric, where a higher ratio is often associated with more stable, fungal-dominated soils and can indicate specific land-use practices [12]. The Gram-positive to Gram-negative bacteria (G+/G-) ratio can serve as an indicator of microbial starvation or physiological stress, such as that induced by heavy metal toxicity [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for PLFA Analysis

The PLFA analysis protocol consists of three consecutive core steps: lipid extraction, fractionation, and methylation, followed by instrumental analysis [4]. The workflow is designed to isolate phospholipids from soil and convert them into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) amenable to gas chromatography.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Lipid Extraction from Soil

- Procedure: Extract lipids from homogenized soil samples (typically 2-3 g freeze-dried weight) using a single-phase mixture of chloroform, methanol, and a phosphate or citrate buffer [1] [4]. The classic Bligh and Dyer method is commonly employed [4].

- Aqueous Buffer Selection: The buffer pH should be selected based on soil properties. An alkaline phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) is standard, but an acidic citrate buffer (pH 4.0) may yield higher lipid recoveries from acidic soils with high organic matter content [4]. The mixture is vigorously shaken and centrifuged to separate the organic phase containing the total lipids.

Step 2: Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Fractionation

- Procedure: The total lipid extract is loaded onto a silica gel solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge. Lipids are then sequentially eluted with solvents of increasing polarity to separate them into neutral lipids, glycolipids, and phospholipids [4].

- Critical Elution Steps:

- Chloroform: Elutes neutral lipids (non-target).

- Acetone: Elutes glycolipids (non-target).

- Methanol: Elutes phospholipids (target fraction for PLFA analysis) [4].

- Technical Note: Recent studies indicate that methanol may not efficiently recover all phospholipids, with a non-negligible proportion sometimes found in the chloroform fraction. Conversely, methanol can also elute some glycolipids (e.g., DGDG), potentially causing interference. This highlights a critical point for method validation [4].

Step 3: Mild Alkaline Methanolysis

- Procedure: The collected methanol fraction containing phospholipids is subjected to a mild transesterification reaction. This is typically achieved using a methanol-KOH or methanol-NaOH solution to release fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) from the phospholipids [4] [12].

- Catalyst Selection: An alkaline catalyst is generally more efficient (mean 86% recovery across phospholipids) and requires shorter reaction times under milder conditions compared to an acidic catalyst (mean 67% recovery) [4].

Step 4: GC-MS Analysis and Peak Identification

- Procedure: The FAME samples are analyzed by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). The FAMEs are identified based on their retention times compared to commercial standards and their characteristic mass spectra.

- Nomenclature: PLFAs are named according to the convention: number of carbon atoms : number of double bonds, followed by the position (ω) of the double bond from the methyl end (e.g., 16:1ω5c). The prefixes i and a indicate iso and anteiso branching, respectively, and "10Me" indicates a methyl group on the 10th carbon atom [14] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for PLFA Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Chloroform, Methanol, Acetone | Organic solvents for lipid extraction and fractionation [4]. |

| Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Alkaline aqueous extractant for neutral to alkaline soils [4]. |

| Citrate Buffer (pH 4.0) | Acidic aqueous extractant for soils with low pH and high organic matter [4]. |

| Silica Gel SPE Cartridges | Solid-phase support for fractionating neutral lipids, glycolipids, and phospholipids [4]. |

| Methanol-KOH/NaOH Solution | Alkaline catalyst for the transesterification (methylation) of phospholipids into FAMEs [4] [12]. |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Standards | Commercial standards for calibrating the GC-MS and identifying PLFA peaks [4]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., non-native PLFA) | Added at the beginning of extraction to quantify recovery efficiency through the entire process [4]. |

| 4-Ethyldodeca-3,6-diene | 4-Ethyldodeca-3,6-diene, CAS:919765-76-7, MF:C14H26, MW:194.36 g/mol |

| C21H15BrN2O5S2 | C21H15BrN2O5S2, MF:C21H15BrN2O5S2, MW:519.4 g/mol |

Methodological Considerations and Comparisons

Technical Validation and Current Limitations

A rigorous evaluation using pure lipid standards has revealed specific efficiencies in the standard protocol that require attention [4]:

- Extraction Efficiency: A phosphate buffer recovered 42-51% of PLFAs from acidic soils and 43-68% from alkaline soils. Citrate buffer was more efficient for acidic soils (43-46%) than for alkaline soils (36-47%).

- Fractionation Concerns: The principle of "like dissolves like" in the SPE step is not perfect. Only 42-50% (acidic soils) and 45-68% (alkaline soils) of phospholipids were recovered in the methanol fraction, while a significant portion was found in the chloroform fraction. Furthermore, 5-16% of a common glycolipid (DGDG) was unexpectedly eluted in methanol, posing a potential interference [4].

- Potential Solutions: To improve accuracy, methods such as replacing chloroform with hexane, increasing elution volumes, or using anion exchange columns are being explored [4].

Comparison with Other Microbial Profiling Methods

PLFA analysis is one of several techniques for measuring microbial abundance. A comparison with other common methods reveals relative strengths and weaknesses [16] [12]:

- vs. EL-FAME (Ester-Linked Fatty Acid Methyl Esters): EL-FAME and PLFA show strong correlation and both correlate well with soil basal respiration. EL-FAME is faster and cheaper, making it an advantageous alternative for many studies, though PLFA may perform better in certain environments like forest soils [16].

- vs. qPCR/ddPCR (Quantitative/Droplet Digital PCR): PLFA and ddPCR are considered the most reliable for assessing the fungi-to-bacteria ratio, with PLFA being the most precise and repeatable. PLFA measures physiological biomass, while PCR methods measure gene copy number, which are not directly equivalent. PLFA results have also been shown to correlate better with soil living biomass activity (e.g., basal respiration) than PCR-based methods [12].

Applications in Environmental Research

PLFA profiling has been successfully applied to understand microbial community dynamics across diverse ecosystems, providing insights into soil health and the impact of environmental stressors.

- Agroecosystems: Studies in temperate alley agroforestry systems show that tree rows shift the PLFA composition towards more fungal biomarkers, promoting carbon sequestration potential [13]. Research also shows that increasing soil organic matter content and fertilization significantly boost total microbial, bacterial, and fungal biomass [17].

- Land Degradation and Restoration: The establishment of artificial grasslands on degraded "black soil mountain" land significantly increased microbial PLFA content and improved soil nutrients, with soil organic carbon and total nitrogen being the main drivers of microbial community structure [15].

- Pollution Monitoring: In soils contaminated with municipal solid wastes, toxic heavy metals like Zn and Cd were found to have the greatest negative impact on microbial populations. Physiological stress indicators, such as the G+/G- ratio, were employed to assess microbial community health [6].

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis is a powerful, phenotype-based technique widely used for characterizing soil microbial biomass and community structure. A foundational principle that underpins its application in microbial ecology is the rapid degradation of phospholipids following cell death, allowing the PLFA profile to represent the community of viable microbes at the time of sampling [1] [6]. This application note details how this unique advantage is leveraged in environmental research and provides standardized protocols for obtaining reliable, high-quality data.

The method's value is particularly evident in studies of environmental stress, where the living microbial community's response is of primary interest. Research on soils contaminated with municipal solid wastes has demonstrated that PLFA profiling can effectively track shifts in key microbial groups—such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and actinomycetes—in response to toxic heavy metals, providing a quantitative picture of the viable community's structure, abundance, and functional status [6].

Theoretical Foundation: The Viability Marker

Biochemical Basis of the "Viability Marker"

The integrity of the PLFA profile as a snapshot of the living microbiome rests on the biochemistry of cell decomposition. Phospholipids are a primary component of microbial cell membranes. Upon cell death, global loss of energy metabolism halts maintenance of cellular structures. The cytoskeleton, a gel-like network of proteins that maintains cell membrane shape, begins to break down due to autolysis, a process initiated by the cell's own enzymes in the absence of energy supply [18].

Concurrently, phospholipids are rapidly degraded by cellular lipases. Because phospholipids are not stored as reserves but are integral to functional membranes, and because the hydrolytic enzymes that break them down are ubiquitous, their presence in a sample strongly indicates intact, living cells [1] [6]. This rapid post-mortem degradation is what allows PLFAs to act as a biomarker for viable cells, distinguishing them from other more persistent lipid classes.

Parallels in Multicellular Organisms

The principle of rapid post-mortem biomolecule degradation is not unique to microbes. Studies on post-mortem interval (PMI) in mammals show that cell morphometry, heavily dependent on membrane and cytoskeletal integrity, degrades rapidly. Fluid shifts causing cell volume alterations and vacuolization are an early event in the PMI, while the loss of the ability to visualize cell membranes altogether is a later event [18]. This decomposition of cellular structure begins within minutes to hours after death.

Supporting evidence comes from conservation biotechnology, where the viability of skin fibroblasts from post-mortem Neotropical deer was found to decrease with increasing post-mortem interval. While cells could be cultured up to 11 hours after death, the highest rates of cell viability and mitotic index were found in samples collected within 5 hours of death [19]. This underscores the critical time-dependence of obtaining viable biological material after death, a principle directly analogous to the use of PLFAs for capturing a profile of viable microbes.

Quantitative Data on Methodological Efficiency

Robust PLFA data requires optimization of each step in the analytical process. Recent studies using pure lipid standards have provided quantitative efficiency evaluations for extraction, elution, and methylation steps, which are critical for accurate estimation of microbial biomass and composition.

Table 1: Extraction Efficiency of Different Aqueous Buffers for Soils of Varying pH

| Soil Type | Extractant Buffer | Reported Extraction Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Acidic (pH ~4.7) | Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | 42 - 51% |

| Acidic (pH ~4.7) | Citrate Buffer (pH 4.0) | 43 - 46% |

| Alkaline (pH ~8.2) | Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | 43 - 68% |

| Alkaline (pH ~8.2) | Citrate Buffer (pH 4.0) | 36 - 47% |

Source: Adapted from Zhang et al. (2025) [4]

Table 2: Efficiency of Lipid Fractionation and Methylation Steps

| Process | Parameter | Efficiency / Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Fractionation | Phospholipids eluted by Methanol (expected) | 42-50% (Acidic Soils); 45-68% (Alkaline Soils) |

| Phospholipids eluted by Chloroform (unexpected) | 36-71% (Acidic Soils); 9-55% (Alkaline Soils) | |

| Glycolipid (DGDG) eluted by Methanol (unexpected) | 16% (Acidic Soils); 5% (Alkaline Soils) | |

| Methylation | Alkaline Catalyst (e.g., KOH) | Mean 86% (across all investigated phospholipids) |

| Acidic Catalyst (e.g., HCl) | Mean 67% (across all investigated phospholipids) |

Source: Adapted from Zhang et al. (2025) [4]

Standardized Experimental Protocols

The following diagram outlines the major steps in the high-throughput PLFA analysis protocol, from soil sampling to data analysis.

Detailed Protocol Steps

Protocol 1: Lipid Extraction from Soil

This step separates total lipids from the soil matrix.

- Materials: Chloroform, Methanol, Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) or Citrate Buffer (pH 4.0), Internal Standard (e.g., methyl nonadecanoate), centrifuge, glass vials.

- Procedure:

- Homogenize 2-3 g of freeze-dried soil.

- Add a known amount of internal standard to correct for extraction efficiency [10].

- Extract lipids using a single-phase mixture of chloroform, methanol, and aqueous buffer (e.g., 1:2:0.8 v/v/v). The choice of buffer (acidic vs. alkaline) can be optimized based on soil pH (see Table 1) [4].

- Shake for 2 hours, then separate the organic phase by centrifugation.

- Evaporate the chloroform phase under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

Protocol 2: Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) for Lipid Fractionation

This step isolates phospholipids from neutral and glycolipids.

- Materials: Silica gel SPE cartridges, chloroform, acetone, methanol.

- Procedure:

- Condition the silica gel cartridge with chloroform.

- Redissolve the total lipid extract in chloroform and load it onto the cartridge.

- Sequentially elute with:

- Chloroform (to collect neutral lipids)

- Acetone (to collect glycolipids)

- Methanol (to collect phospholipids)

- Collect the methanol fraction containing phospholipids and evaporate to dryness.

- Critical Note: Recent studies show incomplete separation, with significant phospholipid loss in chloroform and glycolipid contamination in methanol (see Table 2). Potential solutions include using hexane, increasing elution volumes, or using anion exchange columns [4].

Protocol 3: Mild Alkaline Methanolysis

This step derivatizes phospholipids into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) for gas chromatography analysis.

- Materials: Methanol-KOH solution (or Methanol-HCl for acidic catalysis), hexane, GC vials.

- Procedure:

- Add a methanol-KOH solution to the dried phospholipid fraction.

- Incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes for transesterification.

- Neutralize the reaction with a weak acid.

- Extract the resulting FAMEs into hexane.

- Transfer the hexane phase containing FAMEs to a GC vial for analysis.

- Critical Note: Alkaline catalysis (e.g., KOH) is generally more efficient (86% mean efficiency) than acidic catalysis (67% mean efficiency) and operates under milder conditions [4].

Data Processing and Quality Control

A critical final step is data scaling to account for procedural losses. The recovery of the internal standard added at the beginning of the extraction is used to calculate a scaling factor, which is applied to the concentration of each detected PLFA [10]. This ensures that the reported microbial biomass data are accurate and comparable across samples and batches.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in PLFA Analysis |

|---|---|

| Silica Gel SPE Cartridges | Fractionates total lipid extract into neutral, glyco-, and phospholipids based on polarity. |

| Chloroform, Methanol, Buffer | Single-phase extraction solvent system for liberating lipids from soil and microbial cells. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., 19:0 ME) | Added to sample prior to extraction; its recovery is used to scale and correct final PLFA concentrations for losses. |

| Methanol-KOH Solution | Alkaline catalyst for transesterification, converting phospholipids into volatile Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs). |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Mix | Standard for calibrating the Gas Chromatograph (GC) for accurate identification and quantification of PLFAs. |

Application in Microbial Community Profiling

The completed PLFA analysis provides data that can be interpreted to understand the living soil microbial community. Key biomarkers and ratios are summarized below.

The power of PLFA profiling is demonstrated in its ability to reveal microbial community responses to environmental stressors. For instance, in soils contaminated with heavy metals from municipal solid waste, the following community-level shifts have been observed using these biomarkers [6]:

- Altered Community Structure: Total PLFA and the abundance of key groups (like AMF) often decrease under contamination, indicating a reduction in viable biomass.

- Increased Stress Indicators: The Gram-positive/Gram-negative (GP/GN) ratio can increase, indicating microbial starvation or toxicity stress. The Gram-negative stress ratio (calculated as (cy17:0 + cy19:0)/(16:1ω7c + 18:1ω7c)) can also rise, signaling nutritional limitation or physiological stress.

- Functional Insights: A higher fungal-to-bacterial (F/B) ratio can suggest a shift toward a more fungal-dominated decomposition pathway in stressed systems.

The rapid post-mortem degradation of phospholipids is the cornerstone that makes PLFA analysis a reliable method for profiling the viable microbial community in environmental samples. By implementing the standardized protocols and quality controls outlined here—including the use of internal standards for data scaling and awareness of recent findings on lipid separation efficiency—researchers can generate robust, quantitative data on microbial biomass and community structure. This provides an invaluable phenotypic complement to genomic methods, advancing our understanding of microbial responses in natural and managed ecosystems.

Phospholipid Fatty Acid (PLFA) analysis stands as a cornerstone technique in microbial ecology for quantifying viable microbial biomass and profiling community structure across diverse environments. This methodology has evolved significantly since its inception, transitioning from Bligh and Dyer's fundamental work on lipid extraction to sophisticated applications in contemporary environmental research. The technique leverages the biological fact that phospholipids are essential components of all viable cellular membranes and are rapidly degraded upon cell death, thus providing a snapshot of the living microbial community [20]. PLFA profiling enables researchers to address fundamental questions about microbial community structure and physiological status across ecosystems ranging from pristine soils to contaminated environments [7] [11]. The method's durability over 35 years of application stems from its direct chemical approach that avoids cultivation biases, providing quantitative data on viable biomass that complements DNA-based techniques [7] [1].

Historical Development and Key Methodological Advancements

The PLFA method represents a synthesis of contributions from multiple researchers spanning six decades of methodological refinement. Table 1 summarizes the key historical developments that have shaped contemporary PLFA analysis.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of PLFA Methodological Components

| Time Period | Key Innovators | Methodological Contribution | Impact on PLFA Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Bligh and Dyer | Single-phase chloroform-methanol extraction system | Foundation of modern lipid extraction protocols [21] |

| 1979 | White et al. | Application to environmental samples (marine sediments) | Established PLFA as index of microbial biomass in environmental matrices [21] |

| 1980s | Tunlid, Bååth, Frostegård | Citrate buffer optimization; multivariate statistics for data interpretation | Enhanced extraction efficiency; enabled community pattern recognition [21] |

| 1980s-1990s | Zelles et al. | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns for fractionation | Streamlined separation of phospholipids from other lipids [21] |

| 1990s | Firestone and colleagues | Internal standard (C10:0) and surrogate standard (C19:0) implementation | Improved quantification and recovery assessment [21] |

| 2000s | Buyer and Sasser | High-throughput PLFA method | Enabled larger-scale environmental monitoring studies [10] |

| 2012-present | Global research community | Standardization (ISO methods); large database development | Enhanced reproducibility; enabled cross-study comparisons [1] [21] |

The contemporary PLFA protocol embodies this historical progression through its layered approach to quality control and quantification. The method incorporates two standardization points: a surrogate standard (PC(19:0/19:0)) added prior to extraction to assess overall recovery efficiency, and an internal instrument standard (methyl decanoate, MeC10:0) added prior to GC analysis for quantification [21]. This dual-standard approach represents the culmination of decades of methodological refinement to ensure analytical precision and accuracy across diverse sample types.

Contemporary PLFA Protocol: Detailed Methodology

The modern PLFA analysis protocol comprises four critical phases that transform raw environmental samples into quantitative microbial community data. The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process:

Sample Preparation and Extraction

Proper sample preparation is fundamental to obtaining reliable PLFA data. The initial phase involves:

- Sample Collection and Storage: Collect soil samples into sterile bags and immediately freeze at -80°C until processing. This preservation step maintains microbial community integrity by halting biological activity [21].

- Freeze-Drying: Lyophilize samples to remove water without damaging heat-sensitive lipid structures. This step enhances extraction efficiency and sample homogeneity.

- Sample Weighing: Precisely weigh freeze-dried material into pre-labeled, muffled glass centrifuge tubes. Recommended masses are 0.5 g for organic-rich materials (carbon content >17% wt) and up to 3.0 g for mineral soils [21].

- Quality Control Samples: Include duplicates (every 10 samples) and extraction blanks (every 20 samples) to monitor precision and contamination throughout the process [21].

The extraction phase employs a modified Bligh and Dyer method using a single-phase chloroform-methanol-citrate buffer system (1:2:0.8 v/v/v). The citrate buffer (0.15 M, pH 4.0) has been demonstrated to increase lipid extraction efficiency compared to phosphate buffers, particularly for soils with high organic matter content [21]. The surrogate standard PC(19:0/19:0) is added at the beginning of extraction to monitor procedural recovery.

Fractionation and Derivatization

Following extraction, the crude lipid extract undergoes purification and preparation for gas chromatographic analysis:

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): Silicic acid columns separate phospholipids from neutral lipids and glycolipids. The phospholipid fraction is eluted with methanol followed by chloroform, providing a targeted analyte isolation that increases analytical specificity [21].

- Methanolysis: The isolated phospholipids undergo alkaline methanolysis using methanolic KOH to convert fatty acids to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). This derivatization enhances volatility for subsequent GC analysis [21].

- Internal Standard Addition: Methyl decanoate (MeC10:0) is added prior to GC analysis as an internal instrument standard for quantification.

Instrumental Analysis and Data Processing

The final FAMEs are analyzed by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID):

- Chromatographic Separation: Capillary GC columns provide resolution of individual FAMEs based on chain length, degree of saturation, and branching patterns.

- Peak Identification: Fatty acids are identified by comparison with retention times of known standards and typically include compounds with chain lengths between 14-20 carbon atoms [21].

- Quantification: Concentration of individual PLFAs is calculated based on the internal standard response and adjusted for extraction efficiency using the surrogate standard recovery data.

Recent advancements in data reporting emphasize the importance of standardized quantification. As reflected in current practices like those implemented by NEON (National Ecological Observatory Network), reporting scaled data that accounts for extraction efficiency through internal standard recovery represents community best practice [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful PLFA analysis requires careful attention to laboratory materials and reagents. Table 2 catalogues the essential components of the PLFA research toolkit and their specific functions within the methodology.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PLFA Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Protocol | Quality Control Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Chloroform:methanol:citrate buffer (1:2:0.8) | Single-phase lipid extraction from soil matrix | HPLC grade solvents; citrate buffer pH 4.00±0.02 [21] |

| Surrogate Standard | PC(19:0/19:0) (1,2-dinonadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) | Monitor extraction efficiency and recovery | Added prior to initial extraction [21] |

| Internal Standard | Methyl decanoate (MeC10:0) | Quantification of individual FAMEs by GC-FID | Added prior to instrumental analysis [21] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Columns | Silicic acid columns | Fractionate phospholipids from neutral and glycolipids | Pre-conditioned with chloroform [21] |

| Derivatization Reagent | Methanolic KOH | Transesterification of phospholipids to FAMEs | Freshly prepared to prevent carbonate formation [21] |

| Glassware | Muffle furnace-treated (450°C for 4.5 hours) | Sample processing and extraction | Eliminates organic contaminants [21] |

| Reference Standards | Bacterial acid methyl esters mix | FAME identification and quantification | Commercial certified reference materials |

| 3-Azidopropyl bromoacetate | 3-Azidopropyl Bromoacetate|CAS 921940-77-4 | Bench Chemicals | |

| C20H25BrN2O7 | C20H25BrN2O7|High-Purity Reference Standard | Bench Chemicals |

The critical importance of scrupulous glassware preparation cannot be overstated. All reusable glassware must undergo rigorous cleaning including detergent washing, acid bath (5% HCl) treatment, and final muffling at 450°C for 4.5 hours to eliminate trace organic contaminants that could interfere with the highly sensitive GC detection system [21].

Modern Applications and Interpretative Frameworks

Contemporary applications of PLFA analysis span diverse ecosystems and research questions, leveraging both the biomass quantification and community profiling capabilities of the technique.

Environmental Monitoring and Disturbance Assessment

PLFA profiling has proven particularly valuable in assessing microbial community response to environmental disturbances:

- Forest Management: Research in Pacific Northwest forest ecosystems demonstrated that clearcutting significantly altered PLFA profiles, with microbial biomass (total PLFA) and specific bacterial and fungal biomarkers substantially reduced in 8-year-old clearcuts compared to old-growth stands. However, 25 years after disturbance, microbial communities showed remarkable recovery, approaching the composition of old-growth forests [11].

- Temporal Dynamics: Crucially, these investigations revealed that seasonal temporal changes exerted greater influence on PLFA profiles than stand age differences, highlighting the necessity for multi-season sampling to fully interpret management impacts on soil microbial communities [11].

- Stress Indicator Applications: The technique can detect physiological stress responses through biomarkers like the trans/cis ratio of mono-unsaturated fatty acids, which increased in late summer in response to water stress in forest ecosystems [11].

Integration with Modern Microbial Ecology

PLFA analysis continues to evolve through integration with complementary techniques and large-scale data synthesis:

- Stable Isotope Probing (SIP): When combined with SIP, PLFA analysis can identify specific microbial functional groups responsible for contaminant degradation in environmental systems. This approach provides conclusive evidence of in situ biodegradation by tracking 13C-labeled substrates into microbial membrane lipids [20].

- Global Databases: Recent initiatives have compiled global databases of soil PLFA measurements, encompassing over 12,000 georeferenced samples across all continents. These resources enable cross-system comparisons and meta-analyses of microbial biomass patterns at unprecedented spatial scales [1].

- Community Best Practices: Ongoing methodology refinement includes movement toward standardized data reporting, particularly the use of scaled data that accounts for extraction efficiency through internal standard recovery, as exemplified by NEON protocols [10].

Interpretation Guidelines and Limitations

While PLFA analysis provides valuable insights into microbial communities, appropriate interpretation requires understanding both its capabilities and constraints:

- Biomarker Interpretation: Certain PLFAs serve as general biomarkers for broad microbial groups (e.g., branched saturated PLFAs for Gram-positive bacteria; mono-unsaturated PLFAs for Gram-negative bacteria; 18:2ω6 for fungi), though these assignments represent generalizations rather than absolute specificities [7] [1].

- Quantitative Strengths: The technique provides robust quantification of viable microbial biomass since phospholipids degrade rapidly upon cell death, offering an advantage over DNA-based methods that may detect extracellular DNA from non-viable organisms [20] [1].

- Complementary Approaches: PLFA profiling is most powerful when integrated with other methods such as enzyme activity assays, DNA-based community analysis, and process rate measurements that together provide a more comprehensive understanding of microbial community structure and function [1].

The continued relevance of PLFA analysis in modern microbial ecology rests on its unique capacity to provide quantitative data on viable biomass and community structure at a scale appropriate for ecosystem-level studies, bridging the gap between process measurements and molecular genetic approaches.

From Sample to Data: A Step-by-Step Guide to the PLFA Protocol and Its Applications

Within the framework of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis for microbial community profiling, the initial stage of sample collection, processing, and storage is paramount. The integrity of downstream data and the validity of scientific conclusions are fundamentally dependent on the procedures employed before extraction. PLFA analysis targets the phospholipids of living cell membranes, which are degraded rapidly after cell death [1] [21]. Therefore, protocols must be designed to immediately preserve the in-situ phenotypic state of the microbial community and prevent post-sampling shifts in lipid composition.

Sample Collection Protocols

Field Collection

Soil samples should be collected using sterile tools (e.g., soil corers, trowels) into sterile, pre-labeled bags or containers. For a comprehensive profile, collect multiple sub-samples from the area of interest and composite them to create a representative sample. It is critical to note the sampling date, location, depth, and relevant metadata (e.g., soil type, vegetation cover, land use) [1] [22]. Immediately upon collection, samples should be placed on ice or in a portable freezer to halt microbial activity and minimize changes in community structure during transport to the laboratory.

Initial Storage and Freeze-Drying

Upon arrival at the laboratory, fresh soil samples should be immediately placed in a -80 °C freezer to preserve the living microbial community until processing [23] [21]. For long-term archiving and prior to PLFA extraction, samples must be freeze-dried [23]. Freeze-drying (lyophilization) removes water via sublimation under vacuum, effectively halting all biological activity and stabilizing the lipid profile without the excessive heat that can degrade sensitive compounds. After freeze-drying, the soil should be homogenized using a sterile mortar and pestle and sieved (e.g., through a 2 mm mesh) to remove rocks and root fragments.

Table 1: Sample Handling and Storage Conditions

| Processing Stage | Key Requirement | Rationale | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Collection | Use sterile tools; immediate cooling on ice. | Prevents cross-contamination and halts microbial activity. | Standard microbial ecology practice [21]. |

| Initial Storage | Transfer to -80 °C freezer. | Preserves living community; prevents lipid degradation. | [23] [21] |

| Drying | Freeze-drying is mandatory. | Stabilizes lipids without heat damage; required for dry-weight calculation. | [23] |

| Dry Storage | Room temperature; darkness. | Practical for archives; preserves community structure for analysis. | [24] |

Impact of Storage Conditions on Microbial Community Integrity

The choice of storage condition post-drying is a critical consideration for experimental design, especially when utilizing archived samples. A 2025 study directly compared the effects of frozen storage (typically at -80 °C) versus dry storage (at room temperature) on soil bacterial diversity and functionality [24].

The results demonstrated that the storage method itself significantly influences the measured bacterial community composition and enzymatic activity. However, and crucially for research, the analysis of the impact of environmental factors (e.g., tillage practices) on the bacterial and enzymatic profiles remained consistent between the two storage methods [24]. This indicates that while the absolute values may shift, the capacity to detect biologically meaningful differences related to management practices or treatments is preserved in dry-stored samples. This finding supports the use of properly archived dry soils for longitudinal and retrospective studies.

Table 2: Frozen vs. Dry Storage: A Comparative Analysis

| Aspect | Frozen Storage (-80 °C) | Dry Storage (Room Temperature) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Practice | Common for fresh soils in microbiological studies. | Common for long-term soil archives. |

| Effect on Community | Considered the "gold standard" for preserving fresh community state. | Alters bacterial community composition and enzymatic activity. |

| Experimental Utility | Provides a baseline for the community at the time of freezing. | Maintains consistency in detecting treatment effects over time. |

| Key Finding | N/A | Despite induced changes, dry-stored samples effectively reveal differences linked to soil management [24]. |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the critical decision points and pathways for sample handling from collection to analysis, integrating the storage condition findings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following reagents and materials are critical for the sample preparation phase of PLFA analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Sample Preparation

| Item | Function / Specification | Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Freeze-Dryer | Removes water from frozen samples via sublimation. | Preserves microbial lipids; required before weighing sample for extraction [23]. |

| Analytical Balance | High-precision weighing. | Essential for accurately weighing 0.5-3.0 g of freeze-dried soil [21]. |

| Glassware | Test tubes, vials, pipettes. | Must be meticulously cleaned, muffled at 450°C, and solvent-rinsed to prevent contamination [21]. |

| Sterile Sample Bags | For field collection and storage. | Prevents cross-contamination and preserves sample integrity from point of collection [21]. |

| Cryogenic Storage | -80 °C Freezer. | For initial preservation of fresh soil samples prior to freeze-drying [23] [21]. |

| Soil Sieve | 2 mm mesh aperture. | For removing rocks and root fragments after freeze-drying to homogenize the sample [21]. |

| Cadmium isooctanoate | Cadmium isooctanoate, CAS:30304-32-6, MF:C16H30CdO4, MW:398.82 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vanadium(4+) tetraformate | Vanadium(4+) Tetraformate - CAS 60676-73-5 |

Within the framework of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis for microbial community profiling, the lipid extraction step is foundational. This step determines the subsequent quality and reliability of the microbial biomass and community data. The Bligh and Dyer method is a benchmark technique for the quantitative extraction of lipids from biological matrices, including complex environmental samples like soils and sediments [25] [4]. Its principle is based on creating a single-phase mixture that efficiently permeates cells and solubilizes membrane lipids. This protocol details the application of the Bligh and Dyer method specifically for the initial extraction of total lipids in preparation for PLFA analysis, a critical tool for understanding soil microbial communities and their functions [1] [2].

Principle of the Method

The Bligh and Dyer procedure employs a ternary solvent system of chloroform, methanol, and an aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate or citrate buffer) [25] [4]. The method is performed in two key stages:

- Solid-Liquid Extraction: The sample is homogenized in a specific ratio of chloroform, methanol, and buffer to form a monophasic system. In this single phase, the polar methanol and aqueous buffer disrupt cellular membranes and facilitate the contact between the non-polar chloroform and the hydrophobic lipid components, leading to the efficient extraction of total lipids from the sample matrix [25].

- Liquid-Liquid Partitioning: The addition of more water (and sometimes chloroform) alters the solvent ratios, inducing the formation of a biphasic system. This consists of an upper water-methanol (WR) phase containing non-lipid cellular materials (e.g., sugars, proteins) and a lower chloroform-rich organic (OR) phase containing the extracted lipids [25]. The separation allows for the isolation of the lipid fraction for further processing.

The core principle of "like dissolves like" ensures that phospholipids from microbial membranes are solubilized into the organic phase [25] [4]. However, recent studies using lipid standards have raised questions about the efficiency of subsequent fractionation steps, noting that a significant proportion of phospholipids may be unexpectedly eluted in chloroform during solid-phase extraction clean-up, while methanol may co-elute some glycolipids [4]. Despite these nuances in purification, the Bligh and Dyer extraction itself remains a highly effective first step for total lipid recovery.

Experimental Protocol: Lipid Extraction

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and materials for the Bligh and Dyer lipid extraction.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) | Non-polar solvent that dissolves hydrophobic lipids into the organic phase. Highly toxic; must be used in a fume hood with appropriate PPE [25] [2]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Polar alcohol that disrupts cell membranes and facilitates contact between chloroform and lipids [25]. |

| Phosphate Buffer (P-buffer) | Aqueous component (e.g., 0.1 M, pH 7.4) used to create the monophasic system and control pH during extraction [2] [4]. |

| Citrate Buffer | An acidic aqueous buffer (e.g., pH 4.0) sometimes used as an alternative, particularly for acidic soils, to potentially improve lipid yields [4]. |

| Centrifuge Tubes | Glass or chemically resistant tubes (e.g., 30 mL) with tight-sealing caps for the extraction. |

| Refrigerated Centrifuge | To accelerate phase separation after partitioning. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Table 2: Detailed steps for the Bligh and Dyer lipid extraction process.

| Step | Procedure Description | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Weigh 0.5 - 5 g of freeze-dried, finely-ground soil into a pre-rinsed (hexane) 30 mL glass centrifuge tube. The mass depends on soil organic matter content [2]. | Record exact soil mass. Use gloves to avoid contamination. |

| 2. Monophasic Extraction | In a fume hood, add reagents in this order: P-buffer, CHCl₃, and MeOH. A typical starting ratio is 0.8:1:2 (P-buffer:CHCl₃:MeOH) by volume [2]. Cap tightly, vortex, and shake horizontally at 280 rpm for 1 hour [2]. | Allow soil to wet after buffer addition. Protect tubes from light. The mixture should be a single, homogeneous phase. |

| 3. Phase Separation | Add additional volumes of CHCl₃ and P-buffer (e.g., 1 mL each) to achieve a final common ratio of 1.8:2:2 (P-buffer:CHCl₃:MeOH). This shifts the composition into the biphasic region [25] [2]. Centrifuge at ~1,430 x g for 10 minutes for clear phase separation [2]. | Two distinct layers must be visible after centrifugation. |

| 4. Organic Phase Collection | Carefully decant or use a Pasteur pipette to transfer the lower chloroform (organic) phase to a clean, baked glass tube. Avoid transferring any material from the interphase or upper aqueous phase. | Take care not to disturb the protein disc at the interface. The organic phase contains the total lipids. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete lipid extraction and subsequent fractionation workflow within the PLFA analysis pipeline.

Critical Considerations & Methodological Evaluation

Buffer Selection and Extraction Efficiency

The choice of aqueous buffer can impact extraction efficiency depending on the sample properties. The table below summarizes findings from a recent study evaluating buffer performance [4].

Table 3: Comparison of extraction efficiency using different aqueous buffers on soils of contrasting pH [4].

| Soil Type | Extraction Buffer | Reported Phospholipid Recovery Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic Soil (pH ~4.7) | Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | 42% – 51% | Moderate efficiency in acidic conditions. |

| Citrate Buffer (pH 4.0) | 43% – 46% | Comparable to phosphate buffer. | |

| Alkaline Soil (pH ~8.2) | Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | 43% – 68% | Good to high efficiency. |

| Citrate Buffer (pH 4.0) | 36% – 47% | Lower efficiency than phosphate buffer. |

Solvent Safety and Green Alternatives

- Hazard Mitigation: Chloroform is a known carcinogen, and methanol is toxic [25]. All procedures involving these solvents must be conducted in a fume hood with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves and safety glasses [2].

- Greener Solvent Systems: Research into bio-sourced and less hazardous solvents has identified ethanol and ethyl acetate as a potential substitute pair for methanol and chloroform, respectively. This alternative system has been shown to achieve lipid recovery rates and selectivity almost as effective as the classical chloroform-methanol system for some microorganisms [25].

Limitations and Recent Insights

A critical reevaluation of the standard PLFA workflow has revealed potential pitfalls in the lipid fractionation step that follows Bligh and Dyer extraction. When using silica gel solid-phase extraction to purify phospholipids, the standard elution scheme (chloroform → acetone → methanol) may not achieve perfect separation [4].

- Phospholipid Loss: A significant proportion of phospholipid standards (9%–71%) were recovered in the chloroform fraction, which is intended for neutral lipids only [4].

- Glycolipid Interference: Conversely, a portion of the glycolipid digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG; 5%–16%) was eluted in the methanol fraction, which is supposed to contain only phospholipids [4].

These findings indicate that the final PLFA profile may be biased due to both the loss of target phospholipids and the introduction of non-target lipids, potentially leading to inaccurate estimations of microbial biomass and community structure.

The Bligh and Dyer method remains a robust and widely adopted standard for the initial extraction of lipids in PLFA-based microbial ecology studies. Its effectiveness in solubilizing membrane lipids from complex environmental samples is well-established. However, researchers must be aware of its technical requirements, including solvent hazards and the influence of buffer selection. Furthermore, recent evidence of incomplete lipid class separation during subsequent purification calls for a careful interpretation of PLFA data and highlights the need for ongoing methodological refinements. By understanding both the power and the limitations of this foundational technique, researchers can more accurately profile microbial communities and advance our understanding of their roles in ecosystem functions.

Within the broader context of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis for microbial community profiling, the fractionation step is critical. This process isolates phospholipids from other extracted lipids, such as neutral lipids and glycolipids, ensuring that the subsequent analysis specifically targets the fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) derived from the membranes of living microorganisms [21]. The solid-phase extraction (SPE) protocol described here is designed to provide quantitative recovery of phospholipids, which is fundamental for an accurate assessment of microbial community structure, abundance, and physiological status [26] [6].

Key Principles and Quantitative Data

The goal of fractionation is to separate the phospholipid fraction from the total lipid extract using silica-based solid-phase extraction columns. The quantitative recovery of phospholipids, particularly phosphatidylcholines (PC), is highly dependent on the elution solvent volume and column preconditioning [26].

Table 1: Optimized Elution Conditions for Quantitative Phospholipid Recovery on Silica-Based SPE Columns (0.5 g silica)

| Elution Solvent | Solvent Volume | Target Lipid Class | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform | 5 mL | Neutral Lipids | Elutes simple triglycerides and other non-polar lipids. |

| Acetone | 5 mL | Glycolipids | Elutes glycosphingolipids and other intermediate polarity lipids. |

| Methanol | 10 mL | Phospholipids | Essential for quantitative recovery; a 20:1 v/w (methanol mL to silica g) ratio is required for complete elution of phosphatidylcholines. [26] |

The necessity for adequate methanol volume cannot be overstated. Research has demonstrated that using a methanol-to-silica ratio of 20:1 (v/w) recovers substantially greater amounts of phospholipids and can result in a different PLFA structural profile compared to a lower ratio of 10:1 [26]. Furthermore, preconditioning the SPE columns with methanol is a mandatory step to ensure quantitative recovery of phospholipids [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns: Silica-based columns (100 mg to 1 g silica bed mass). The protocol is scalable [26].

- High-Purity Solvents: Chloroform, acetone, and methanol. Ensure solvents are HPLC grade or higher to prevent contamination.

- Glassware: Pre-cleaned glass vials (e.g., 10 mL, 15 mL) for solvent and fraction collection.

- Nitrogen Evaporation System: For gentle evaporation of solvents under a stream of inert nitrogen gas.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Column Preconditioning: Pass 5 mL of methanol through the silica SPE column to activate the silica and remove any traces of water. This step is crucial for achieving quantitative recovery [26]. Follow this by equilibrating the column with 5 mL of chloroform. Do not allow the column to dry out after preconditioning.

Sample Loading: Transfer the total lipid extract (dissolved in a small volume of chloroform, ~100-200 µL) onto the preconditioned SPE column.

Fraction Elution: Elute different lipid classes sequentially using solvents of increasing polarity into separate, labeled glass vials.

- Neutral Lipid Fraction: Pass 5 mL of chloroform through the column. This fraction contains triglycerides, cholesterol, and other non-polar lipids.

- Glycolipid Fraction: Pass 5 mL of acetone through the column. This fraction removes glycolipids.

- Phospholipid Fraction: Pass 10 mL of methanol through the column to elute the phospholipids quantitatively [26]. This fraction contains the microbial membrane phospholipids for PLFA analysis.

Solvent Evaporation: Evaporate the methanol from the phospholipid fraction to dryness under a stream of nitrogen gas. The dried phospholipid extract is now ready for the methanolysis step to convert phospholipids into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) [21].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the fractionation process and its role within the broader PLFA analysis workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Materials for Solid-Phase Extraction Fractionation

| Item | Function in Protocol | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Silica SPE Columns | Stationary phase for chromatographic separation of lipid classes. | Silica mass (e.g., 0.5 g) determines sample capacity and eluent volumes. [26] |