Synthetic Microbial Community Design and Assembly: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of synthetic microbial community (SynCom) design and assembly.

Synthetic Microbial Community Design and Assembly: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of synthetic microbial community (SynCom) design and assembly. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of synthetic ecology, from leveraging division of labor to enhance functional robustness. It details cutting-edge methodological strategies for consortium construction, including bottom-up assembly, automated high-throughput techniques, and genetic engineering. The review further addresses critical challenges in community stability and optimization, and systematically covers validation protocols and comparative functional analyses. By synthesizing recent advances, this article serves as a strategic guide for harnessing SynComs in biotechnological and clinical applications, including therapeutic development and personalized medicine.

The Principles and Promise of Synthetic Ecology

Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) represent a paradigm shift in microbial biotechnology, moving beyond single-strain engineering to the design of multi-population systems. Defined as artificially created communities composed of two or more selected microbial species, SynComs are engineered to perform specific, enhanced, or novel functions that are not typically found in nature [1]. This approach leverages the inherent advantages of microbial consortia, which are prevalent in natural environments and often demonstrate superior robustness and functionality compared to monocultures [2].

The transition from single strains to consortia is driven by several fundamental advantages. SynComs enable division of labor, allowing different metabolic tasks to be partitioned among community members, thereby reducing the metabolic burden on individual strains [3] [1]. They can exhibit enhanced stability against invasions from external species and maintain functionality despite evolutionary pressures [3]. Furthermore, consortia provide the capacity to assemble complex functions that no single organism could perform independently, making them particularly valuable for sophisticated biotechnological applications [4].

Defining Synthetic Microbial Communities

In the context of research and biotechnology, SynComs are specifically defined as "host-associated or free-living microbial groups that are assembled or engineered for understanding fundamental biological principles or for applications with novel capabilities" [5]. These communities are constructed through the rational co-culture of selected species based on their known traits and interactions [3].

SynComs differ from other microbial assemblages in their design philosophy and construction:

- Artificial Communities: Composed of wild populations that do not naturally coexist, facilitated through laboratory introduction under controlled conditions [1].

- Semi-Synthetic Communities: Combine metabolically modified organisms with naturally occurring communities, allowing interaction between engineered and wild-type populations [1].

True SynComs are distinguished by their deliberate design based on functional traits, ecological principles, and specific performance objectives, moving beyond simple co-culture to strategic community engineering [6].

Applications of Synthetic Microbial Communities

Therapeutic Applications

In biomedicine, SynComs show transformative potential for treating diseases linked to microbial dysbiosis. Engineered consortia are being developed as personalized probiotics that can restore healthy microbial balance in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic disorders, and neurodevelopmental conditions [7]. Synthetic biology tools like CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing enable precise modification of gut microbes to produce therapeutic compounds, target pathogens, or modulate host immune responses [7]. These approaches allow for the development of sophisticated living therapeutics that can sense and respond to disease states in real-time.

Bioremediation and Environmental Applications

SynComs offer powerful solutions for environmental challenges through enhanced biodegradation capabilities. Constructed from native hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, specific consortia have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in breaking down poly-aromatic hydrocarbons, with one combination of Bacillus pumilis KS2 and Bacillus cereus R2 achieving 84.15% degradation of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) within five weeks [2]. Similar approaches have been successfully applied to pesticide contamination, where SynComs of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus polymyxa significantly enhanced degradation rates of persistent pesticides like Aldrin [2].

Table 1: Environmental Applications of Synthetic Microbial Communities

| Application Area | Target Contaminant | Key Microbial Strains | Efficiency/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil Spill Remediation | Poly-aromatic hydrocarbons | Bacillus pumilis KS2, Bacillus cereus R2 | 84.15% TPH degradation in 5 weeks |

| Pesticide Degradation | Aldrin and other pesticides | Pseudomonas fluorescens, Bacillus polymyxa | 48.2% degradation by single strain; 54.0% by consortium |

| PFAS Degradation | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances | Pseudomonas plecoglossicida 2.4-D, Labrys portucalensis F11 | Identification via 16S rRNA sequencing and metabolomics |

Industrial and Bioproduction Applications

The industrial implementation of SynComs enables complex biomanufacturing processes through distributed metabolic pathways. A prominent example is the co-culture of autotrophic Synechococcus elongatus engineered for sucrose export with heterotrophic Escherichia coli for biofuel production, creating a self-sustaining system that synchronously grows and produces valuable compounds [2]. Similarly, consortia have been designed for bioplastic production, such as the stable co-culture of S. elongatus and Halomonas boliviensis that continuously produces polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) from carbon dioxide over extended periods without antibiotic selection [2].

The division of labor principle has been successfully applied to complex biochemical production, as demonstrated by a two-strain E. coli system engineered with complementary pathway segments for resveratrol biosynthesis [3]. This approach minimizes metabolic burden on individual strains while optimizing overall pathway efficiency.

Experimental Protocols for SynCom Construction

Full Factorial Construction Method

The full factorial construction protocol represents a methodological advancement for systematically assembling all possible combinations from a library of microbial strains. This approach enables comprehensive exploration of community-function landscapes and identification of optimal consortia [8].

Table 2: Required Materials for Full Factactorial Construction

| Material/Equipment | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Strains | 8 purified isolates | Consortium members |

| 96-Well Plates | Sterile, U-bottom | Community assembly and cultivation |

| Multichannel Pipette | 8- or 12-channel | High-throughput liquid handling |

| Growth Media | Appropriate for all strains | Consortium cultivation |

| Plate Reader | With temperature control | Biomass and function measurement |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Strain Preparation: Grow each of the m microbial strains to mid-log phase in separate cultures. Adjust cell densities to standardized OD600 values to ensure consistent starting concentrations.

Binary Coding System: Assign each strain a unique binary identifier. For m=8 strains, use binary numbers from 00000001 to 10000000, where each bit represents the presence (1) or absence (0) of a specific strain [8].

Initial Assembly Setup: In column 1 of a 96-well plate, assemble all combinations of the first three strains (2^3 = 8 communities) following binary order: well A1=000, B1=001, C1=010, D1=011, E1=100, F1=101, G1=110, H1=111.

Iterative Expansion:

- Transfer column 1 to column 2 using a multichannel pipette.

- Add strain 4 (binary 1000) to all wells of column 2, generating all combinations of strains 1-4 (16 communities).

- Continue this process: duplicate existing columns and add subsequent strains until all m strains are incorporated [8].

Cultivation and Measurement: Incubate plates under appropriate conditions. Monitor community functions (e.g., biomass production, metabolite synthesis) using plate readers or analytical sampling.

This methodology enables a single researcher to assemble all possible combinations of up to 10 species in under one hour using standard laboratory equipment, dramatically increasing accessibility for comprehensive consortium screening [8].

Functional Trait-Based Design Protocol

An alternative approach prioritizes microbial strains based on functional traits rather than comprehensive combinatorial assembly. This strategy selects community members according to specific metabolic capabilities relevant to the desired application [6].

Protocol Steps:

Functional Profiling: Screen candidate isolates for specific functional traits using high-throughput assays:

Genomic Analysis: Complement experimental profiling with genomic trait identification:

Interaction Assessment: Screen pairwise interactions between functionally-selected strains using:

- Cross-streaking assays for antagonism

- Metabolic cross-feeding experiments

- Growth enhancement/inhibition co-cultures

Consortium Assembly: Combine strains based on functional complementarity and positive interactions, typically constructing communities of 5-20 members depending on application complexity.

Validation and Optimization: Test constructed SynComs for target functionality and stability over multiple generations, adjusting composition as needed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SynCom Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs | Precise genetic modification of consortium members [7] |

| DNA Assembly Methods | Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Assembly | Construction of synthetic genetic circuits [7] |

| Signaling Molecules | Acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), Autoinducer-2 | Engineering intercellular communication [1] [4] |

| Selection Agents | Antibiotics, Auxotrophic complementation markers | Maintenance of community composition and genetic elements |

| Metabolic Substrates | Specific carbon/nitrogen sources, Prebiotics | Directing community function and composition [6] |

| 6-Methyldodecanoyl-CoA | 6-Methyldodecanoyl-CoA, MF:C34H60N7O17P3S, MW:963.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-Asu(OAll)-OH | Fmoc-Asu(OAll)-OH, MF:C26H29NO6, MW:451.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Quorum Sensing Circuit for Population Control

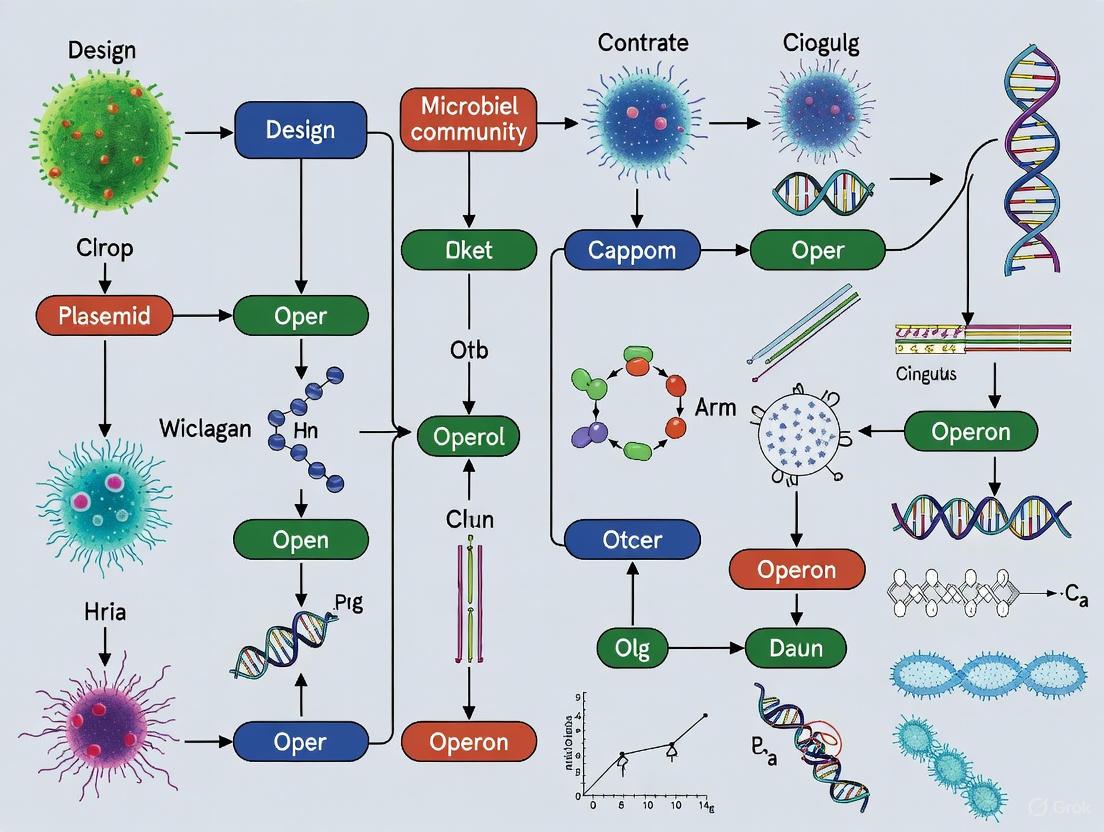

Figure 1: Quorum Sensing Feedback Circuit

SynCom Design and Assembly Workflow

Figure 2: SynCom Design and Assembly Workflow

Synthetic Microbial Communities represent a sophisticated framework for addressing complex challenges across therapeutics, environmental remediation, and industrial biotechnology. The methodologies outlined—from full factorial construction to functional trait-based design—provide researchers with systematic approaches for consortium development. As the field advances, integrating computational modeling with high-throughput experimental validation will be crucial for realizing the full potential of SynComs. The continued refinement of genetic tools, signaling mechanisms, and ecological design principles will further enhance our ability to program microbial collectives for targeted functions, ultimately establishing SynComs as powerful platforms for biological innovation.

Synthetic microbial communities represent a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving from engineering single strains to designing complex multispecies consortia. This approach leverages core ecological principles to create systems with capabilities surpassing those of monocultures [9] [10]. The foundational advantages driving this field forward include division of labor for distributed biochemical processing, functional robustness through distributed network architecture, and evolutionary stability that enables long-term persistence [11] [12]. These engineered communities show transformative potential across biotechnology, from sustainable bioproduction to therapeutic interventions [9] [13]. This article details the experimental frameworks and mechanistic insights underpinning these advantages, providing researchers with practical tools for consortium design and implementation.

Division of Labor for Enhanced Metabolic Capability

Conceptual Foundation and Quantitative Evidence

Division of labor (DOL) is an evolutionary strategy where community members specialize in distinct metabolic tasks, creating a distributed metabolic network that efficiently converts complex substrates into desired products [14]. This approach partitions metabolically costly pathways across specialized strains, reducing individual cellular burden and enabling more complex biotransformations than possible in single organisms [10].

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence for Division of Labor Advantages

| Community System | Specialized Functions | Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli & S. cerevisiae Consortium | E. coli: Taxadiene production;S. cerevisiae: Oxidation steps | Enhanced oxygenated taxane production vs. single species | [10] |

| Cellulosimicrobium cellulans & Pseudomonas stutzeri | Metabolic exchange of asparagine, vitamin B12, isoleucine | Central role in stable SynComs; >80% plant biomass increase | [15] |

| Trichoderma reesei & Engineered E. coli | T. reesei: Cellulase secretion;E. coli: Isobutanol production | Direct conversion of plant biomass to biofuels | [10] |

| Theoretical Framework | Narrow-spectrum resource utilization | Increased Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) | [15] |

Protocol: Designing Communities for Metabolic Division of Labor

Objective: Construct a stable, cooperative microbial consortium through complementary auxotrophies [10].

Materials:

- Genetically engineered auxotrophic strains (e.g., amino acid or vitamin auxotrophs)

- Minimal media lacking specific essential nutrients

- 96-well plates or shake flasks

- Spectrophotometer for OD measurements

Procedure:

- Strain Selection and Validation: Select partner strains with complementary metabolic capabilities. For example, use one strain engineered to produce a metabolite that a partner strain cannot synthesize, and vice versa [10].

- Monoculture Control Experiments: Grow each auxotrophic strain separately in minimal media to confirm impaired growth without metabolite cross-feeding.

- Consortium Assembly: Inoculate strains together in minimal media. A common method uses a 1:1 initial inoculation ratio, though this can be optimized [10].

- Growth and Stability Monitoring: Measure community composition (e.g., via selective plating, flow cytometry, or strain-specific markers) and total biomass over multiple growth-dilution cycles (e.g., 48-72 hour transfers) [10].

- Interaction Analysis: Use genome-scale metabolic modeling (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis) to predict and verify metabolic exchanges. Computational tools like BacArena or COMETS can simulate spatial and temporal dynamics [13] [10].

Functional Robustness Through Distributed Networks

Mechanisms and Stabilizing Interactions

Functional robustness emerges when community-level functions are maintained despite fluctuations in individual member populations or environmental conditions [12]. This resilience is engineered through distributed network architectures where multiple members can perform redundant functions or where intercellular feedback mechanisms regulate population dynamics.

Table 2: Engineering Strategies for Functional Robustness

| Engineering Strategy | Mechanism | Example | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Feedback | Density-dependent regulation of growth or toxin production | AutoCD-designed two-strain system with cross-protection mutualism [12] | Maintains stable population ratios |

| Metabolic Redundancy | Multiple species encode similar key functions | Function-based SynCom design from metagenomes [13] | Buffers against species loss |

| Spatial Structuring | Creates physical niches and local interaction gradients | Microfluidic separation, 3D-printing, patterned biofilms [10] | Enhances coexistence and stabilizes trade |

The AutoCD (Automated Community Designer) computational workflow exemplifies a rigorous approach to designing robust communities. This method generates all possible genetic circuit combinations using available parts (strains, bacteriocins, QS systems), filters non-viable candidates, and uses Approximate Bayesian Computation with Sequential Monte Carlo (ABC SMC) to identify designs with the highest probability of maintaining stable steady states in a chemostat [12].

Figure 1: Automated Computational Design Workflow. The AutoCD pipeline uses Bayesian methods to identify optimal community designs from a space of possible genetic circuit configurations [12].

Protocol: Full Factorial Community Assembly for Robustness Screening

Objective: Empirically map community-function landscapes by constructing all possible combinations from a microbial strain library to identify optimally robust consortia [8].

Materials:

- Library of m microbial strains

- 96-well plates

- Multichannel pipette

- Sterile growth medium

Procedure (Binary Assembly Logic):

- Binary Encoding: Assign each strain a unique binary identifier. For m strains, this creates 2^m possible combinations [8].

- Initial Plate Setup: In column 1 of a 96-well plate, assemble all combinations of the first three strains (2^3 = 8 wells), following binary order: well A1=000 (no strains), B1=001 (strain 3 only), ..., H1=111 (all three strains) [8].

- Iterative Expansion:

- Transfer column 1 to column 2.

- Use a multichannel pipette to add strain 4 (binary 1000) to all wells in column 2. This creates all combinations of strains 1-4 [8].

- Transfer columns 1-2 to columns 3-4.

- Add strain 5 (10000) to columns 3-4. Repeat this duplication and addition process until all m strains are incorporated [8].

- Functional Screening: Incubate plates and measure your function of interest (e.g., biomass, product titer, pathogen suppression) for each community.

- Interaction Analysis: Identify optimal consortia and quantify pairwise and higher-order interactions using statistical models.

Evolutionary Stability and Long-Term Coexistence

Trade-Off Mechanisms for Stable Coexistence

Evolutionary stability ensures that synthetic communities maintain their composition and function over extended timescales, resisting invasion by cheaters or collapse into monocultures. Insights from long-term evolution experiments reveal that stable coexistence is often underpinned by fundamental physiological trade-offs [16].

The E. coli Long-Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) provides critical insights. Communities of L- and S-strains persisted for tens of thousands of generations due to a cross-feeding interaction: L-strains excrete acetate during glucose growth, which S-strains efficiently utilize after glucose depletion [16]. This coexistence is stabilized by two key trade-offs:

- Growth Rate vs. Metabolite Excretion: Faster growth inevitably leads to higher excretion of metabolic byproducts (e.g., acetate) due to protein costs of energy metabolism [16].

- Growth Rate vs. Metabolic Flexibility: Fast-growing specialists cannot rapidly switch to alternative nutrients, creating ecological niches for slower-growing generalists [16].

Figure 2: Trade-Offs Stabilizing Evolutionary Dynamics. Physiological constraints create complementary niches that prevent competitive exclusion in evolving communities [16].

Protocol: Assessing Evolutionary Stability in Chemostats

Objective: Quantify the long-term stability of synthetic communities and their resistance to invasion under controlled evolution [16] [12].

Materials:

- Pre-assembled synthetic community

- Chemostat system with controlled dilution rate

- Candidate invader strains (optional)

- Equipment for periodic sampling and analysis

Procedure:

- System Setup: Inoculate the synthetic community into a chemostat with a single limiting resource (e.g., glucose). Set the dilution rate (D) below the maximum growth rate (μₘâ‚â‚“) of all members [12].

- Long-Term Propagation: Maintain the community for extended periods (e.g., 100-500 generations), ensuring continuous growth through regular dilution.

- Monitoring and Sampling: Periodically sample the community to:

- Quantify strain ratios (using selective plating, flow cytometry, or qPCR).

- Measure metabolic byproducts (e.g., via HPLC).

- Archive samples for whole-genome sequencing to track evolutionary adaptations [16].

- Invasion Assay (Optional): Introduce a potential "cheater" strain (e.g., a generalist that could exploit community resources) and monitor whether the resident community resists invasion [16].

- Stability Metrics: Calculate the coefficient of variation of strain ratios over time. Lower values indicate higher stability. The community is considered evolutionarily stable if strain ratios remain within a defined range and the community resists invasion over the experimental timeframe.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Community Engineering

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Principle | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GMMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes and exchanges | Calculating Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) and Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) to predict stable consortia [15] |

| Bacteriocins (e.g., MccV, Nisin) | Narrow- or broad-spectrum antimicrobial peptides for targeted population control | Engineering amensal interactions to stabilize community composition [12] |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Density-dependent genetic regulation for inter-strain communication | Building feedback loops that control bacteriocin production or resource utilization [12] [10] |

| Phenotype Microarrays (Biolog) | High-throughput profiling of carbon source utilization | Quantifying resource utilization width and niche overlap for candidate strains [15] |

| GapSeq | Tool for automated construction of genome-scale metabolic models | Generating metabolic models from genome sequences for use in tools like BacArena [13] |

| BacArena | Computational toolkit for dynamic metabolic modeling of communities | Simulating growth and interactions of multiple strains in a shared environment [13] |

| COMETS | Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis in spatial environments | Modeling community dynamics on surfaces or in structured environments [10] |

| MiMiC2 | Computational pipeline for function-based SynCom selection | Designing communities from metagenomic data by selecting strains encoding key functions [13] |

| 16-Methyldocosanoyl-CoA | 16-Methyldocosanoyl-CoA, MF:C44H80N7O17P3S, MW:1104.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diosmetin 3',7-Diglucuronide-d3 | Diosmetin 3',7-Diglucuronide-d3, MF:C28H28O18, MW:655.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Synthetic microbial communities are artificially created consortia composed of two or more selected microbial species, designed to function as model systems for evaluating ecological roles, structural characteristics, and functional behaviors in a controlled manner [1]. The engineering of these communities represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, enabling researchers to program specific ecological interactions—including mutualism, competition, and predation—for applications in biotechnology, medicine, and drug development [17]. Unlike natural communities, synthetic ecosystems offer reduced complexity and enhanced controllability, making them invaluable for investigating fundamental ecological principles and engineering consortia with predictable, robust behaviors [11].

The rational design of these interactions allows for division of labor, reduced metabolic burden on individual species, expanded metabolic capabilities, and enhanced resilience to environmental perturbations [17]. For drug development professionals, these engineered communities offer novel platforms for understanding host-microbe interactions, modeling disease states, and developing live biotherapeutics [13]. This protocol outlines specific methodologies for designing, constructing, and analyzing synthetic microbial communities with programmed ecological interactions, providing a framework for implementing these systems in research and therapeutic applications.

Foundational Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Defined Ecological Interactions in Engineered Systems

Table 1: Programmable Ecological Interactions in Synthetic Microbial Consortia

| Interaction Type | Defining Characteristics | Engineering Mechanism | Biotechnological Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Mutual benefit through metabolic exchange | Cross-feeding of essential metabolites [17] | Division of labor in bioproduction pathways [17] |

| Competition | Inhibition of growth through antagonism | Bacteriocin-mediated killing [17] | Population control and community stability [17] |

| Predation | Predator consumes prey organisms | Engineering of algivorous protists [18] | Food web dynamics and population cycling [18] |

| Commensalism | One benefits, the other unaffected | Unidirectional resource production | Community assembly and succession |

| Amensalism | One inhibited, the other unaffected | Antibiotic production without resistance | Pathogen suppression in biocontrol |

Computational and Theoretical Foundations

The design of synthetic microbial communities benefits from computational approaches that predict community dynamics prior to experimental implementation. Genome-scale metabolic modeling using tools like BacArena provides in silico evidence for cooperative strain coexistence, simulating growth dynamics over defined time periods (e.g., 7 hours) in a spatially structured environment [13]. For more complex community design, function-based selection approaches like MiMiC2 leverage metagenomic data to select strains encoding key functions identified in target ecosystems, weighting functions differentially enriched in specific states (e.g., diseased versus healthy individuals) [13].

Network analysis combined with trait-based approaches enhances the prediction of specific interactions, particularly for predator-prey relationships. Recent research demonstrates that while network analyses alone generate numerous correlations between predatory protists and algae (51-138 correlations in polar biocrust systems), only 4.7-9.3% of these correlations actually link predators to suitable prey when evaluated through trait-based filtering [18]. This integration of computational prediction with functional trait assignment significantly increases confidence in interaction prediction, with 82% of investigated correlations being experimentally verified [18].

Experimental Protocols for Engineering Ecological Interactions

Protocol 1: Engineering Mutualism via Syntrophic Cross-Feeding

Objective: Establish obligate mutualism through metabolic interdependency to create stable, cooperative consortia.

Materials:

- Auxotrophic bacterial strains (e.g., E. coli MG1655 derivatives)

- Minimal media lacking specific essential nutrients

- Inducer molecules (IPTG, aTc) for regulated gene expression

- Shaking incubator for liquid cultures

- Spectrophotometer for OD600 measurements

Methodology:

- Strain Engineering:

- Design sender and receiver strains with complementary metabolic deficiencies and capabilities.

- Implement in the sender strain a genetic circuit for production and export of a metabolite essential for the receiver strain's growth. Use well-characterized promoters (e.g., P({LtetO-1}), P({trc})) for controlled expression [17].

- Implement in the receiver strain a genetic circuit for production and export of a different metabolite essential for the sender strain's growth.

Cross-Feeding Validation:

- Culture each strain independently in minimal media supplemented with the essential metabolite to verify growth dependency.

- Co-culture both strains in minimal media without supplementation, monitoring growth of both populations via strain-specific markers (e.g., fluorescent proteins) over 24-48 hours.

- Quantify metabolic exchange products using HPLC or LC-MS at 4-hour intervals.

Stability Assessment:

- Perform serial passaging (1:100 dilution daily) for 10-15 cycles, monitoring population ratios via flow cytometry or selective plating.

Model interaction stability using the Lotka-Volterra cooperative equations:

( \frac{dN1}{dt} = r1N1(1 - \frac{N1}{K1} + \alpha{12}\frac{N2}{K1}) )

( \frac{dN2}{dt} = r2N2(1 - \frac{N2}{K2} + \alpha{21}\frac{N1}{K2}) )

where (N1) and (N2) are population densities, (r1) and (r2) are growth rates, (K1) and (K2) are carrying capacities, and (\alpha{12}) and (\alpha{21}) are cooperation coefficients.

Validation Metrics:

- Co-culture stability maintained for >10 generations

- Balanced population ratios (between 1:10 and 10:1)

- Metabolic complementation confirmed via extracellular metabolomics

Protocol 2: Programming Competition via Antagonistic Interactions

Objective: Implement tunable competition mechanisms to control population dynamics in mixed communities.

Materials:

- Gram-positive (e.g., Lactococcus lactis) and/or Gram-negative (e.g., E. coli) bacterial strains

- Bacteriocin genes (e.g., lactococcin A, colicins)

- Quorum sensing components (lux, las, rpa, or tra systems)

- Antibiotics for selection pressure

- Microplate readers for continuous monitoring

Methodology:

- Toxin-Antitoxin System Engineering:

- Clone bacteriocin or toxin genes under control of inducible promoters or QS-responsive promoters in the predator strain.

- For bidirectional competition, engineer both strains with toxin genes and corresponding resistance mechanisms.

- For unidirectional competition, engineer only one strain with toxin production and ensure the other lacks resistance.

Communication Circuit Implementation:

- Utilize orthogonal quorum sensing systems (e.g., rpa and tra systems in E. coli) to minimize crosstalk [17].

- For predator strain, link QS signal reception to toxin gene expression.

- For prey strain, implement resistance genes (e.g., immunity proteins for bacteriocins) under constitutive or inducible promoters.

Dynamic Monitoring:

- Co-culture engineered strains in appropriate media with monitoring of OD600 and fluorescence every 30 minutes for 24 hours.

- Induce competition at mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5) via addition of autoinducer molecules or chemical inducers.

Model population dynamics using modified Lotka-Volterra competition equations:

( \frac{dNp}{dt} = rpNp(1 - \frac{Np + \alpha{px}Nx}{K_p}) )

( \frac{dNx}{dt} = rxNx(1 - \frac{Nx + \alpha{xp}Np}{Kx}) - \gamma NpN_x )

where (Np) is predator density, (Nx) is prey density, (\alpha) terms represent competition coefficients, and (\gamma) represents predation rate.

Validation Metrics:

- Predator strain dominance within 4-8 hours of induction

- Dose-dependent response to inducer concentration

- Cyclic population dynamics in bidirectional competition systems

Protocol 3: Establishing Predator-Prey Relationships

Objective: Construct protist-bacteria or protist-algae predator-prey pairs for studying microbial food web dynamics.

Materials:

- Predatory protists (e.g., cercozoans from polar biocrusts) [18]

- Bacterial or algal prey strains

- Culture media specific to each organism

- Cell counting chambers (hemocytometer)

- PCR reagents for DNA-based identification

Methodology:

- Strain Selection and Validation:

- Identify potential predator-prey pairs through co-occurrence network analysis of natural communities followed by trait-based filtering [18].

- Isclude predatory cercozoans and algal prey (green algae or ochrophytes) from environmental samples using dilution-to-extinction culturing.

- Confirm trophic relationship through microscopy and food range experiments.

Interaction Quantification:

- Co-culture predators and prey at varying initial ratios (1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) in appropriate media.

- Sample every 12 hours for 5-7 days to monitor population dynamics via:

- Direct counting using fluorescent microscopy

- Species-specific qPCR targeting 18S rRNA genes for protists and 16S rRNA genes for bacteria

- Chlorophyll fluorescence for algal prey

Calculate predation rates using functional response models:

( \frac{dP}{dt} = aPN - dP )

( \frac{dN}{dt} = rN - aPN )

where (P) is predator density, (N) is prey density, (a) is attack rate, (r) is prey growth rate, and (d) is predator death rate.

Network Analysis Validation:

- Compare experimentally determined interactions with those predicted through network analyses like FlashWeave.

- Calculate precision of network predictions: Precision = (True Positives) / (True Positives + False Positives)

- Refine network inference parameters based on experimental validation.

Validation Metrics:

- Clear oscillation patterns in population dynamics

- Correlation between network centrality measures and predation intensity

- 82% validation rate of predicted interactions [18]

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Engineering Microbial Interactions

| Reagent/Circuit | Function | Example Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal QS Systems (lux, las, rpa, tra) [17] | Inter-strain communication | Activating toxin expression in competition systems | Minimal crosstalk between systems; modular design |

| Bacteriocins (lactococcin A, colicins) [17] | Mediating competitive interactions | Population control in consortia | Species-specific killing activity |

| Metabolic Cross-feeding Modules [17] | Establishing mutualistic exchanges | Division of labor in bioproduction | Essential metabolite auxotrophies |

| GapSeq [13] | Genome-scale metabolic modeling | Predicting strain coexistence | Generates metabolic models compatible with BacArena |

| BacArena [13] | Spatial-temporal metabolic modeling | Simulating community growth dynamics | Compatible with GapSeq models; spatial simulation |

| MiMiC2 Pipeline [13] | Function-based community selection | Designing host-specific SynComs | Uses metagenomic data; weights ecosystem-critical functions |

| FlashWeave [18] | Network analysis | Predicting putative predator-prey interactions | Handles cross-kingdom associations; statistical robustness |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Metabolic Modeling Workflow for Predicting Strain Coexistence

Genetic Circuitry for Programmed Competition

Integrated Workflow for Synthetic Community Design

Data Analysis and Interpretation Guidelines

Quantitative Metrics for Interaction Strength

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters for Ecological Interaction Analysis

| Parameter | Definition | Measurement Method | Typical Range in Engineered Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperation Coefficient (α) | Strength of mutualistic benefit | Lotka-Volterra model fitting | 0.1-0.8 (dimensionless) |

| Competition Coefficient (γ) | Strength of competitive inhibition | Population dynamics modeling | 0.5-2.0 (dimensionless) |

| Predation Rate (a) | Attack rate of predator on prey | Functional response fitting | 0.01-0.5 mL/cell/day |

| Cross-feeding Efficiency | Metabolite transfer efficiency | LC-MS of extracellular metabolites | 5-60% depending on system |

| Interaction Stability | Duration of stable coexistence | Serial passage experiments | 10-100+ generations |

| Network Centrality | Position in interaction network | Graph theory analysis | Correlates with predation intensity [18] |

Statistical Validation and Model Selection

For robust quantification of engineered interactions, implement the following statistical framework:

Model Selection Criteria:

- Use Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to compare different ecological models (e.g., competitive vs. predatory)

- Perform residual analysis to validate model assumptions

- Apply bootstrap methods to estimate parameter confidence intervals

Network Validation Metrics:

- Calculate precision and recall for predicted interactions: Precision = TP/(TP+FP); Recall = TP/(TP+FN)

- Compare experimentally validated interactions with network predictions

- Use trait-based filtering to improve prediction accuracy from 4.7% to 82% validation rates [18]

Community Stability Analysis:

- Calculate coefficient of variation for population densities over time

- Measure recovery time after perturbation (e.g., dilution, antibiotic pulse)

- Quantify resistance to invasion by additional species

These protocols provide a comprehensive framework for designing, constructing, and analyzing synthetic microbial communities with programmed ecological interactions. The integration of computational prediction with experimental validation enables robust engineering of mutualism, competition, and predation for applications in basic research and therapeutic development.

The intricate complexity of natural microbiomes presents a significant challenge for researchers aiming to harness microbial communities for biotechnological and therapeutic applications. Natural ecosystems harbor a huge reservoir of taxonomically diverse microbes that are important for plant growth and health, but this vast diversity makes it challenging to pinpoint the main players important for life support functions [6]. Synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) have emerged as a key technology for reducing this complexity and unraveling the molecular and chemical basis of microbiome functions [6]. By designing simplified microbial systems, researchers can dissect microbial interactions and reproduce microbiome-associated phenotypes in controlled conditions.

The field of synthetic ecology is increasingly looking to natural microbiome principles to inform the rational design of these microbial consortia. This approach represents a paradigm shift from engineering individual microorganisms to engineering entire microbial communities, offering advantages such as functional compartmentalization, enhanced robustness, and the ability to perform complex functions through division of labor [3]. This article outlines the fundamental principles derived from natural microbiomes and provides detailed application notes and protocols for the design, construction, and validation of synthetic microbial communities for pharmaceutical and biotechnological applications.

Foundational Principles from Natural Microbiomes

Natural microbiomes exhibit several key characteristics that provide guiding principles for synthetic community design. These principles can be systematically categorized to inform engineering strategies.

Table 1: Key Principles from Natural Microbiomes and Their Engineering Implications

| Natural Principle | Mechanistic Basis | Engineering Implication | Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Redundancy | Multiple taxa perform similar metabolic functions, ensuring ecosystem stability. | Design communities with backup members for critical functions to enhance resilience. | Maintains consortia performance against environmental fluctuations and evolution. |

| Niche Differentiation | Species coexist by partitioning resources (e.g., spatial, nutritional). | Engineer complementary metabolic pathways and spatial structures to minimize competition. | Enables stable, diverse communities; prevents one species from dominating. |

| Metabolic Interdependency | Cross-feeding and syntrophic relationships where metabolites of one species are substrates for another. | Create obligate mutualisms by knocking out essential genes in different members. | Increases community stability and drives the coordinated function of desired pathways. |

| Context-Dependent Function | Microbial traits and interactions are modulated by environmental factors (e.g., pH, temperature). | Control environmental variables (e.g., in bioreactors) to fine-tune community behavior and output. | Allows external steering of community composition and function. |

The selection of microbial members for a SynCom can follow various strategies. The taxonomy-based approach relies on identifying core or representative members across different environmental samples [6]. Alternatively, the function-based approach prioritizes strains based on specific genomic traits or metabolic capabilities, such as the presence of CAZymes, secretion systems, antifungal metabolites, or phytohormones [6]. A more advanced strategy involves differential abundance analysis, where taxa significantly associated with a desired phenotype in natural environments are selected for consortium assembly [6].

Natural microbial communities also demonstrate remarkable structural and functional resilience. This resilience can be engineered into SynComs through the inclusion of taxa that exhibit positive interactions, which enhance diversity and productivity, and by controlling spatial organization to prevent the invasion of cheater strains that consume public goods without contributing to community function [19].

Computational and Experimental Design Framework

The rational design of SynComs is increasingly guided by an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a formalized framework adopted from traditional engineering disciplines [19]. This cycle begins with a rational design based on quantitative modeling, proceeds to physical construction, tests the function and performance of the microbiome, and incorporates new knowledge from these tests into subsequent design cycles.

Integrated Workflow for SynCom Design

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for designing synthetic microbial communities, integrating computational and experimental methods as informed by natural principles.

Protocol: Function-Based SynCom Design from Environmental Samples

This protocol outlines a method for constructing a SynCom based on functional traits identified in a natural microbiome, suitable for applications in bioremediation or host-associated therapies.

Principle: Microbial taxa are selected based on genomic traits (e.g., specific metabolic pathways, biosynthetic gene clusters) associated with a target phenotype, rather than taxonomic identity alone [6].

Materials:

- Environmental samples (e.g., soil, plant rhizosphere, human gut) from habitats exhibiting the target phenotype.

- Culture media appropriate for the target microbial groups.

- DNA extraction kits.

- Reagents for 16S rRNA gene amplicon and metagenomic sequencing.

- Bioinformatic software suites (e.g., QIIME 2, HUMAnN 2, antiSMASH).

Procedure:

- Sample Collection & Phenotyping: Collect multiple environmental samples with contrasting phenotypes (e.g., disease-suppressive vs. disease-conducive soil [6]). Document relevant metadata (pH, temperature, host health status).

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Extract total genomic DNA and perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing to profile the community's functional potential.

- Functional Trait Analysis:

- Annotate metagenomic assemblies for key functional genes (e.g., chitinases, phytases, antibiotic synthesis clusters) using databases like CAZy and MIBiG [6].

- Use differential abundance analysis tools (e.g.,

DESeq2,ANCOM) to identify gene families and pathways enriched in the desired phenotype group [20].

- Strain Isolation & Genotyping: Isplicate microbial strains from the source environment using selective media. Sequence the genomes of isolates and screen for the presence of the functional traits identified in Step 3.

- In Vitro Functional Assay: Conduct high-throughput phenotypic profiling of isolates to confirm predicted functions (e.g., antagonism against pathogens on agar plates, phosphate solubilization in Pikovskaya’s agar) [6].

- SynCom Assembly: Assemble a candidate SynCom from confirmed, functionally-characterized isolates. The initial composition can be guided by the relative abundance of these functions in the source metagenome.

Quantitative Analysis and Validation

A critical, yet often overlooked, aspect of SynCom validation is the move from relative to absolute abundance measurements. Standard 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing provides relative abundances, where an increase in one taxon necessitates an apparent decrease in others, complicating biological interpretation [21]. Absolute quantification is essential for accurately determining whether a taxon's abundance has genuinely changed between conditions.

Protocol: Absolute Abundance Quantification Using dPCR Anchoring

This protocol provides a rigorous method for quantifying the absolute abundance of individual taxa, appropriate for samples from diverse environments, including those with high host DNA contamination like mucosal samples [21].

Principle: Digital PCR (dPCR) is used to precisely count the number of 16S rRNA gene copies in a sample. This absolute count is then used to convert relative abundances from amplicon sequencing into absolute cell numbers [21].

Materials:

- Extracted DNA sample.

- dPCR system (e.g., Bio-Rad QX200).

- TaqMan assay or EvaGreen dye for 16S rRNA gene.

- Reagents for 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

- Normalization and analysis software.

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction & Quality Control: Extract DNA using a protocol validated for efficiency across different sample types (e.g., stool vs. mucosa). The extraction efficiency should be tested using a spiked-in control community [21].

- Digital PCR (dPCR):

- Partition the DNA sample mixed with the 16S rRNA gene assay into thousands of nanoliter droplets.

- Run the PCR to endpoint.

- Count the number of positive droplets. Using Poisson statistics, calculate the absolute concentration of 16S rRNA gene copies in the original sample (copies/µL).

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing: Perform standard library preparation and sequencing on the same DNA extract. Use a conservative cycling protocol to limit chimera formation [21].

- Data Integration:

- Process sequencing data to obtain relative abundances for each taxon.

- Calculate the absolute abundance for each taxon using the formula: Absolute Abundance (Taxon A) = Relative Abundance (Taxon A) × Total 16S rRNA gene copies (from dPCR)

Validation Notes:

- The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) must be established. For example, one study defined an LLOQ of 4.2 × 10^5 16S rRNA gene copies per gram for stool and 1 × 10^7 copies per gram for mucosa [21].

- Samples with total microbial loads below 1 × 10^4 16S rRNA gene copies are prone to contamination and should be interpreted with caution [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for SynCom Research

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in DNA Standards | Known quantities of exogenous DNA added to a sample to calibrate and convert relative sequencing data to absolute abundance. | Quantifying total microbial load in complex samples like gut mucosa [21]. |

| Selective Culture Media | Media formulated to favor the growth of specific microbial taxa based on their metabolic capabilities (e.g., carbon source, antibiotic resistance). | Isolation of target functional groups from complex environmental samples [6]. |

| Gnotobiotic Growth Systems | Sterile environments (e.g., germ-free mice, plant growth systems) that can be colonized with known, defined microbial communities. | Testing the function and host effects of SynComs in a controlled, biologically relevant context [6]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSEMM) | Computational models that simulate the metabolic network of an organism, predicting nutrient consumption and waste production. | Predicting metabolic interactions and potential competition/synergy between SynCom members in silico [6]. |

| Microfluidic Droplet Generator | Device used to create monodisperse water-in-oil droplets for single-cell encapsulation or dPCR. | High-throughput screening of microbial interactions or performing digital PCR for absolute quantification [21]. |

| (Benzyloxy)benzene-d2 | (Benzyloxy)benzene-d2, MF:C13H12O, MW:186.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,4-dimethylidenedecanedioyl-CoA | 3,4-dimethylidenedecanedioyl-CoA, MF:C33H52N7O19P3S, MW:975.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Notes for Drug Development

The principles of synthetic ecology are paving the way for next-generation live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) and microbiome-based therapies. Engineered SynComs offer a more robust and controllable alternative to single-strain probiotics or undefined fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) [22] [23].

Application Note 1: Designing a SynCom for Targeted Drug Delivery Challenge: Deliver a therapeutic agent specifically to a disease site (e.g., a tumor) in response to a local microbial stimulus. Solution: Design a SynCom where one member is engineered to produce a specific enzyme in response to a tumor-associated metabolite. A second member is engineered to activate a prodrug via this enzyme. Protocol Considerations:

- Use quorum sensing (QS) systems or other microbial signaling molecules (e.g., AHLs, AI-2) for inter-strain communication within the SynCom [23].

- Encapsulate the SynCom in a biomaterial that ensures co-localization and survival of the constituent strains at the target site.

Application Note 2: Optimizing a Therapeutic SynCom for Stability Challenge: Maintaining a stable, defined community composition after administration to a host. Solution: Implement ecological principles from natural microbiomes to enforce stability. Protocol Considerations:

- Induce Obligate Mutualism: Genetically engineer cross-feeding dependencies, for example, by knocking out essential amino acid biosynthesis genes in different members [3] [19].

- Spatial Structuring: Co-encapsulate the SynCom in a hydrogel or fiber that creates micro-niches, mimicking the structure of a biofilm and promoting stable coexistence [19].

The following diagram maps the decision process for engineering stable and effective therapeutic SynComs, directly applying lessons from natural microbiomes.

The rational design of synthetic microbial communities represents a convergence of ecology, microbiology, and systems biology. By learning from the strategies employed by natural microbiomes—such as functional redundancy, niche differentiation, and metabolic interdependency—researchers can move beyond simplistic taxonomy-based assemblies to create robust, functional consortia. The integrated framework of computational prediction, functional trait-based selection, and rigorous quantitative validation outlined in this article provides a roadmap for advancing SynCom applications. As the field matures, the adoption of absolute quantification and the implementation of ecological principles for enhancing stability will be critical for translating SynComs from laboratory models into reliable tools for drug development, biotechnology, and environmental restoration.

Strategies for Construction and Translational Applications

The bottom-up assembly of synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) represents a core strategy in synthetic ecology for constructing defined consortia with predictable and robust functions. This approach involves the intentional selection and combination of microbial strains based on their known functional traits, mirroring the rational design principles established in protein engineering and synthetic biology [3]. The fundamental premise is that by understanding the individual pieces—the microbial species and their metabolic, physiological, and interaction capabilities—we can solve the "puzzle" of community assembly to achieve a target biotechnological or therapeutic outcome [3]. This methodology stands in contrast to top-down approaches that manipulate entire communities, offering greater control, reproducibility, and mechanistic insight. In the context of drug development and therapeutic discovery, bottom-up assembly enables the creation of defined Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) that can circumvent the safety and reproducibility concerns associated with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) [24]. The following sections detail the specific protocols, data, and reagents that underpin this rational design process, providing a framework for researchers to engineer consortia for applications ranging from gut health to sustainable agriculture.

Core Methodologies and Data

The trait-based selection pipeline integrates computational and experimental biology to move from a desired ecological function to a stable, functioning consortium. Key strategies include function-based selection from metagenomic data and metabolic modeling to predict community stability and cooperation.

Function-Based Selection Using MiMiC2

The MiMiC2 pipeline enables the automated design of SynComs based on functional profiles derived from metagenomic data [13]. The process begins by generating binarized Pfam vectors for both the input metagenome(s) and a collection of candidate genomes. Functions are then weighted to prioritize those that are core to a healthy ecosystem (>50% prevalence) or differentially enriched in a diseased state. The algorithm iteratively selects the highest-scoring genome from the collection, whose functional profile best matches the target metagenome, and adds it to the SynCom [13]. The table below summarizes key parameters and their quantitative impact on community design from a representative study.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters in Function-Based SynCom Design (MiMiC2)

| Parameter | Description | Typical Value/Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function Weight | Additional weight given to functions prevalent in >50% of target metagenomes. | Default: 0.0005; optimizable via parameter sweep [13] |

| Differentially Enriched Function Weight | Additional weight for functions significantly associated with a target state (e.g., disease). | Default: 0.0012; based on Fisher's exact test (P-value < .05) [13] |

| Simulation Time | Duration for in silico growth simulation in metabolic models. | 7 hours; may limit inclusion of slow-growing taxa [13] |

| SynCom Size | Number of member strains in a typical consortium. | Average ~13 members; can range from a few to over 100 [13] [24] |

Metabolic Modeling for Predicting Coexistence

After selecting candidate strains, genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) are employed to provide in silico evidence for cooperative growth and stability before experimental validation [13]. Tools like GapSeq are used to generate the metabolic models, which are then simulated in environments such as BacArena or Virtual Colon. These simulations test whether the selected strains can coexist by modeling metabolic exchanges and resource competition. For instance, simulating the growth of a 10-member SynCom in the Virtual Colon model over 7 hours provided evidence for strain cooperation prior to its experimental use in a colitis model [13].

Experimental Protocols

This section outlines a generalized, step-by-step protocol for the bottom-up assembly and validation of a synthetic microbial community, synthesizing methods from skin and gut microbiome studies [13] [25].

Protocol: Assembly and Testing of a Synthetic Microbial Community

Objective: To rationally design, construct, and functionally validate a synthetic microbial community in vitro and in vivo.

Stage 1: In Silico Design and Selection

- Define Target Function: Clearly define the community's objective (e.g., production of a specific metabolite, pathogen inhibition, induction of a host phenotype).

- Select Candidate Strains:

- Source Strains: Create a strain library from a relevant environment (e.g., host-specific biobank, culture collection). Prioritize isolates with fully sequenced and annotated genomes [26].

- Trait-Based Filtering: Filter the library based on known traits related to the target function (e.g., presence of biosynthetic gene clusters, ability to utilize specific carbon sources, known immunomodulatory properties) [3] [24].

- Function-Based Selection (Optional): For a more unbiased approach, use a computational pipeline like MiMiC2 to select strains that recapitulate the functional profile (Pfam abundance) of a target metagenome, such as one from a healthy donor [13].

- Predict Coexistence with Metabolic Modeling:

- Use GapSeq (v1.3.1) to generate genome-scale metabolic models for each candidate strain [13].

- Simulate the growth of strain pairs and the full consortium in a defined medium using a tool like BacArena. This step helps identify potential competitive bottlenecks or synergistic cross-feeding interactions [13].

Stage 2: Community Assembly and In Vitro Validation

- Cultivation and Consortium Construction:

- Individually cultivate each selected strain in its optimal medium under appropriate atmospheric conditions (aerobic, microaerophilic, or anaerobic) [26] [25].

- Standardized Inoculum: Harvest cells in mid-logarithmic phase. Wash and resuspend in a sterile buffer or medium to prepare a standardized inoculum for each strain (e.g., OD600 of 1.0) [25].

- Combination: Combine the strains in a single vessel containing a shared, defined medium. The initial inoculum ratio can be equal or weighted based on predicted growth rates from metabolic modeling [3] [25].

- Measure Community Function and Stability:

- Growth Metrics: Monitor community density (e.g., OD600) and composition over time by plating on selective media or via sequencing (16S rRNA gene amplicon or shotgun metagenomics) [25].

- Functional Output: Quantify the target function (e.g., concentration of a produced molecule, degradation of a substrate) using analytical methods like HPLC or MS.

- Passaging: Perform serial passaging to a fresh medium at a fixed dilution ratio and time interval to assess the community's compositional and functional stability over multiple generations [3].

Stage 3: In Vivo Validation

- Animal Model Testing:

- Utilize germ-free or antibiotic-treated animal models (e.g., mice) [13] [24].

- Gavage: Administer the assembled SynCom to the animals via oral gavage.

- Monitoring: Track the colonization dynamics of the community in the host environment (e.g., fecal sampling via metagenomics) and measure the relevant host phenotype (e.g, disease severity, immune markers, metabolite levels in blood or tissue) [13] [25].

- Downstream Multi-omic Analysis:

- At endpoint, collect tissue or content samples from relevant sites (e.g., colon, skin).

- Extract DNA for metagenomics to confirm community composition and RNA for metatranscriptomics to analyze community-wide gene expression in situ [25].

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Bottom-Up Community Design Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental pipeline for the rational design of a synthetic microbial community.

Diagram Title: Rational SynCom Design Workflow

Quorum-Sensing Communication Module

In engineered consortia, communication between strains is often facilitated by synthetic quorum-sensing (QS) circuits. The following diagram details the structure of a generalized QS-based genetic circuit used for coordinated behavior.

Diagram Title: QS Circuit for Consortia Communication

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents, tools, and computational resources critical for executing the bottom-up assembly of synthetic microbial communities.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for SynCom Construction

| Category | Item / Tool Name | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | MiMiC2 Pipeline | Automated function-based selection of SynCom members from genome collections based on metagenomic functional profiles [13]. |

| GapSeq | Generates genome-scale metabolic models from genomic data, predicting metabolic capabilities and auxotrophies [13]. | |

| BacArena | Simulates the growth and interactions of metabolic models in a defined environment, predicting community stability and metabolite exchange [13]. | |

| Genetic Parts | Quorum Sensing Systems | AHL-, AI-2, or AIP-based systems enable precise, density-dependent communication between engineered strains in a consortium [27]. |

| Disease-Specific Biosensors | Genetic circuits (e.g., based on promoters PnorV, PpchA) that sense pathophysiological signals like nitric oxide (NO) or butyrate [27]. | |

| Chassis Organisms | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) | A well-characterized probiotic chassis commonly engineered for diagnostic and therapeutic applications in the gut [27]. |

| Commensal Bacteria | Clostridia, Bacteroides, and other anaerobic gut isolates that serve as chassis for host-specific intervention [24]. | |

| Experimental Models | Virtual Colon (in silico) | A computational model of the human colon environment used to simulate SynCom behavior and metabolic output prior to in vivo testing [13]. |

| Gnotobiotic Mice | Germ-free animals essential for in vivo validation of SynCom colonization, stability, and host phenotype effect without background microbiota [13] [24]. | |

| Culture & Assembly | Defined Media | Cultivation media with known composition, essential for testing metabolic cross-feeding and maintaining community stability in vitro [26]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Provides an oxygen-free atmosphere for the cultivation and manipulation of obligate anaerobic members of synthetic consortia [25]. | |

| (Tyr34)-pth (7-34) amide (bovine) | (Tyr34)-pth (7-34) amide (bovine), MF:C156H244N48O40S2, MW:3496.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Z)-2,3-dehydroadipoyl-CoA | (Z)-2,3-dehydroadipoyl-CoA, MF:C27H42N7O19P3S, MW:893.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Top-down microbiome engineering represents a powerful strategy for achieving targeted functions by manipulating existing native microbial communities through selective environmental pressures, rather than constructing new consortia from isolated strains. This approach leverages the inherent ecological robustness, diversity, and pre-adapted functional capabilities of natural communities, steering them toward desired outcomes through controlled manipulation of their growth and operational conditions [28]. In the broader context of synthetic microbial community design, top-down approaches complement bottom-up strategies (which assemble defined microbial members into new consortia) and can be integrated into hybrid "middle-out" frameworks that combine the strengths of both paradigms [29] [30]. The fundamental premise of top-down engineering is that environmental variables—such as nutrient availability, pH, temperature, and feedstocks—act as selective forces that reshape community structure and dynamics, thereby enhancing specific biochemical pathways or metabolic functions valuable for biotechnology, environmental remediation, and therapeutic development [28] [3].

Core Principles and Mechanisms of Community Manipulation

Theoretical Foundation of Selective Pressure

Top-down manipulation operates on the ecological principle that environmental parameters serve as filters that selectively enrich for microbial taxa whose functional traits are advantageous under the imposed conditions. This selective pressure reshapes the community's taxonomic composition, interaction networks, and emergent metabolic output. The approach is particularly effective for functions that are naturally distributed across multiple members of a microbial community, such as the degradation of complex substrates or the production of specific metabolites through synergistic relationships [28]. By manipulating extrinsic factors, researchers can steer the community toward a configuration that optimally performs the target function without requiring detailed knowledge of the individual microbial members or their genetic makeup. This makes top-down approaches highly valuable for exploiting the functional potential of unculturable microorganisms or communities of high complexity [30].

Key Environmental Levers for Community Steering

Successful top-down engineering relies on identifying and optimizing critical environmental variables that exert the strongest selective influence on community structure and function. The most potent levers include:

- Carbon Source and Nutrient Availability: The type and concentration of carbon sources (e.g., lignocellulosic waste, glycerol, C1 gases) and the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio strongly select for taxa with specialized metabolic capabilities, determining the community's functional orientation [28] [3].

- Physicochemical Conditions: Parameters including pH, temperature, oxygen availability, and salinity act as fundamental filters that determine which microorganisms can thrive, thereby shaping community composition and stability [31].

- Process Operational Parameters: In controlled bioreactor systems, factors such as hydraulic retention time, feeding regime, and mixing intensity can be manipulated to enrich for communities with desired growth rates and metabolic outputs [28].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and key control points in a top-down community engineering process:

Application Protocols for Top-Down Community Manipulation

Protocol 3.1: Environmental Parameter Optimization for Function Enhancement

This protocol details the systematic optimization of environmental parameters to steer native microbial communities toward enhanced functional output, applicable to both environmental and engineered systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Source microbial community (e.g., environmental sample, anaerobic digester sludge)

- Basal growth medium appropriate for the target community

- Carbon/nitrogen source variants for selective pressure

- pH buffers and adjustment solutions

- Bioreactor systems or multi-well culture plates

- Analytical equipment for functional assessment (HPLC, GC-MS, spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Community Inoculum Preparation:

- Collect representative samples of the native microbial community.

- If necessary, pre-adapt the community to laboratory conditions through 2-3 transfer cycles in basal medium.

Experimental Design Setup:

- Establish multiple treatment conditions varying key parameters:

- Carbon sources (e.g., lignocellulose, glycerol, organic acids)

- Temperature gradients (e.g., 25°C, 37°C, 55°C)

- pH ranges (e.g., 5.5, 7.0, 8.5)

- Oxygen availability (aerobic, microaerophilic, anaerobic)

- Include appropriate controls representing baseline conditions.

- Establish multiple treatment conditions varying key parameters:

Selective Pressure Application:

- Inoculate triplicate cultures for each condition with standardized community biomass.

- Maintain selective conditions throughout the experiment, monitoring and adjusting parameters as needed.

- For serial transfer experiments: When cultures reach mid-log phase or designated growth stage, transfer a predetermined percentage (typically 1-10%) to fresh medium with identical selective conditions.

Monitoring and Sampling:

- Track community density and function at regular intervals (e.g., optical density, substrate consumption).

- Collect samples for community analysis (16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics) and functional measurements (product quantification, enzyme assays).

- Continue selective pressure for multiple generations (typically 5-20 transfers) until functional stabilization is observed.

Functional Validation:

- Assess the target function of the stabilized communities under the selective conditions.

- Compare performance against baseline communities and between different selective regimes.

- Validate functional stability through additional transfer cycles without selective pressure changes.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If community function declines unexpectedly, reduce the strength of selective pressure (e.g., less extreme pH, additional nutrients).

- If contamination occurs, increase the specificity of selective conditions or implement antibiotic treatments targeting common contaminants.

- If function stabilizes at suboptimal levels, introduce additional selective pressures sequentially rather than simultaneously.

Protocol 3.2: Serial Transfer Enrichment for Functional Specialization

This protocol employs repeated batch transfers under specific conditions to enrich for microbial subpopulations capable of performing target functions, particularly effective for substrate utilization and metabolite production.

Materials and Reagents:

- Native microbial community sample

- Selective medium with target substrate(s)

- Sterile anaerobic conditions (for anaerobic processes)

- Centrifuges and filtration equipment for biomass separation

Procedure:

- Primary Enrichment:

- Inoculate native community into medium containing the target substrate as primary carbon source.

- Incubate under selective environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH) until significant substrate utilization is observed.

Serial Transfer Regimen:

- Transfer 5-10% of the culture volume to fresh selective medium at regular intervals (typically 24-72 hours, based on growth kinetics).

- Monitor substrate consumption and product formation at each transfer.

- Continue transfers until consistent functional performance is achieved (typically 5-15 cycles).

Community Stabilization:

- Once functional stability is reached, preserve the enriched community in glycerol stocks at -80°C.

- Characterize the stabilized community through phylogenetic analysis and functional profiling.

Performance Benchmarking:

- Compare the functional capacity of the enriched community against the original inoculum under identical conditions.

- Assess the stability of the enhanced function under non-selective conditions to determine the persistence of the acquired traits.

Quantitative Outcomes and Performance Metrics

The effectiveness of top-down approaches is demonstrated by significant enhancements in target functions across diverse application domains. The following table summarizes representative performance data from various implementation studies:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Top-Down Engineered Microbial Communities

| Target Function | Waste Source/Substrate | Key Environmental Manipulations | Performance Outcome | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomethane Production | Lignocellulosic biomass | Temperature (mesophilic ~37°C), retention time, C:N ratio | 0.14-0.39 L biogas/g volatile solids | [28] |

| Biomethane Production | Agricultural residues | Nutrient supplementation, pH control, temperature optimization | 0.19 L/g total solids | [28] |

| Medium-Chain Carboxylic Acids | Mixed organic waste | pH selection (~5.5), retention time control, feedstock composition | High carboxylate yields, alternative to fossil-derived chemicals | [28] |

| Biohydrogen Production | Various organic wastes | Strict anaerobic conditions, short retention times, pH control | Higher selectivity and lower energy vs. chemical methods | [28] |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (Bioplastics) | Glycerol (biodiesel waste) | Nutrient limitation (N, P, O), feast-famine cycles | Efficient biopolymer accumulation | [28] |

| Waste Valorization | C1 gases (CO2, CO) | Gas composition control, pressure, specialized medium | Conversion to alcohols, fatty acids, chemicals | [28] |

The functional enhancements achieved through top-down approaches demonstrate the powerful selective effects of environmental parameters on native microbial communities. In many cases, the performance of these manipulated communities rivals or exceeds that of rationally designed bottom-up synthetic consortia, particularly for complex, multi-step processes such as the degradation of heterogeneous substrates [28]. The stability of these functionally enhanced communities varies with the specificity and consistency of the applied selective pressure, with some maintained functional traits for extended periods even after removal of the original selective conditions, indicating potential evolutionary adaptation or ecological stabilization of the altered community state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of top-down microbial community engineering requires specific laboratory resources and analytical tools. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in typical experimental workflows:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Top-Down Community Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Growth Media | Applying nutritional pressure to enrich specific metabolic capabilities | Medium with target substrate (e.g., lignin, cellulose) as sole carbon source |

| pH Buffers & Modifiers | Maintaining precise pH conditions as selective filter | Phosphate buffers for neutral pH; organic acids for acidic conditions |

| Oxygen Scavengers/Control Systems | Creating aerobic/microaerophilic/anaerobic conditions | Anaerobic chambers, gas exchange systems, oxygen scavenging chemicals |

| Nutrient Limitation Supplements | Imposing nutrient stress to redirect metabolic fluxes | Nitrogen/phosphorus-limited media for PHA production |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Selecting against specific microbial groups | Bile salts for gut microbiome studies; antibiotics for contamination control |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Community composition analysis before/after selection | Metagenomic DNA extraction for 16S rRNA sequencing and functional gene analysis |

| Metabolite Analysis Standards | Quantifying metabolic outputs and function | HPLC/GC standards for organic acids, alcohols, methane quantification |

| High-Throughput Cultivation Systems | Parallel testing of multiple selective conditions | Multi-well plates, automated bioreactor arrays for parameter optimization |

| Cryopreservation Reagents | Long-term storage of functionally enhanced communities | Glycerol stocks for community preservation and experimental replication |

| Mes-peg2-CH2-T-butyl ester | Mes-peg2-CH2-T-butyl ester, MF:C11H22O7S, MW:298.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Heme Oxygenase-1-IN-3 | Heme Oxygenase-1-IN-3, MF:C22H18BrFN4O2S, MW:501.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Broader Research Frameworks

Top-down approaches gain maximum utility when integrated with complementary strategies in synthetic microbial ecology. The emerging "middle-out" paradigm combines the functional richness and stability of top-down manipulated native communities with the precision and controllability of bottom-up designed consortia [29] [30]. This integration can be visualized as a cyclical process where insights from each approach inform and refine the other:

This integrative framework enables researchers to first use top-down approaches to identify optimally performing community configurations and key functional members under realistic selective conditions, then employ bottom-up strategies to reconstruct minimal functional consortia based on these insights, and finally apply the refined understanding back to improve top-down manipulation parameters [29] [28]. The combination of these approaches is particularly powerful for addressing complex biotechnological challenges where both functional performance and ecological stability are critical for long-term success, such as in continuous bioprocessing systems, environmental bioremediation applications, and therapeutic microbiome interventions.