Untangling the Microbial Web: A Practical Guide to Handling Multicollinearity in Microbiome Feature Selection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of multicollinearity in microbiome feature selection.

Untangling the Microbial Web: A Practical Guide to Handling Multicollinearity in Microbiome Feature Selection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of multicollinearity in microbiome feature selection. We begin by establishing foundational knowledge, exploring what multicollinearity is and why it is particularly problematic in high-dimensional, compositional microbiome data. We then systematically review and demonstrate methodological solutions, including specialized regularization techniques, dimensionality reduction, and network-based approaches. The guide delves into practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world datasets, followed by a comparative analysis of validation frameworks to ensure biological relevance and model generalizability. Our aim is to equip scientists with a practical toolkit to select robust, interpretable microbial features for downstream biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

The Multicollinearity Challenge in Microbiomes: Why Correlation Clouds Your Biomarker Discovery

In microbiome feature selection research, multicollinearity is a statistical phenomenon where two or more microbial taxa (features) in your dataset are highly correlated. This means one predictor's abundance can be linearly predicted from the others with substantial accuracy. In the context of a thesis on "Dealing with multicollinearity in microbiome feature selection research," this is a critical problem because many common statistical and machine learning models assume predictor independence. Multicollinearity does not reduce the model's predictive power but severely undermines the reliability of identifying which specific microbes are driving an observed effect (e.g., association with a disease state), as it inflates the variance of coefficient estimates and makes them unstable and difficult to interpret.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My regression model for linking microbial OTUs to inflammation markers has high overall accuracy (R²), but the p-values for individual OTUs are insignificant or coefficients are counter-intuitive. Is multicollinearity the cause? A: Very likely. High model performance with nonsensical individual feature statistics is a classic symptom. The correlated features are "sharing" the explanatory power, making it impossible for the model to assign credit to any single one. The high variance inflates p-values.

Q2: How can I quickly diagnose multicollinearity in my ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) abundance table before complex modeling? A: Calculate the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). A VIF > 10 (or a more conservative threshold of >5) for a feature indicates problematic multicollinearity.

- Protocol: 1) Center and scale your abundance data (e.g., CLR transform). 2) Fit an ordinary least squares regression for each taxon, predicting it from all other taxa. 3) Calculate VIF = 1 / (1 - R²) from that regression. Most statistical software (R:

car::vif(), Python:statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence.variance_inflation_factor) automates this.

Q3: I used a regularized method (LASSO) for feature selection, but the selected taxa keep changing with small data subsampling. Why? A: This instability is a direct consequence of multicollinearity. When many taxa are correlated, LASSO may arbitrarily select one from a correlated group. Small data perturbations can flip this arbitrary choice. Consider using ensemble or stability selection techniques to improve robustness.

Q4: Are correlation matrices sufficient to detect all multicollinearity in microbiome data? A: No. Pairwise correlation (e.g., Spearman) only detects linear relationships between two features. Multicollinearity can be more complex, involving one feature being predicted by a combination of several others (multicollinearity). Use VIF or condition index/correlation matrix eigenvalues for a complete diagnosis.

Data Presentation: Multicollinearity Diagnostics Comparison

Table 1: Key Diagnostic Metrics for Multicollinearity

| Diagnostic Tool | Calculation/Threshold | Interpretation | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Correlation | Absolute Spearman's Ï > 0.7-0.8 | Indicates strong linear relationship between two features. | Initial exploratory data analysis. |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | VIF = 1 / (1 - R²_i). Threshold: VIF > 10 (or >5). | Quantifies how much the variance of a coefficient is inflated due to correlation with others. | Direct, per-feature assessment in regression contexts. |

| Condition Index (CI) | CI = √(λmax / λi). Threshold: CI > 30. | Derived from eigenvalue decomposition of the correlation matrix. High CI indicates dependency among features. | Identifying the presence and number of multicollinear patterns. |

| Tolerance | Tolerance = 1 / VIF. Threshold: < 0.1. | Inverse of VIF. The amount of variance in a predictor not explained by others. | Alternative, equivalent view to VIF. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Multicollinearity with VIF in R

- Data Preprocessing: Start with a taxa abundance table (rows=samples, columns=features/OTUs/ASVs). Apply a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation using the

compositions::clr()function to address compositionality. - Model Fitting: Fit a linear model (e.g.,

lm()) where your outcome of interest (e.g., cytokine level) is the dependent variable and all CLR-transformed taxa are independent variables. - VIF Calculation: Use the

car::vif(model)function to compute VIF values for each taxon. - Interpretation: Iteratively remove features with VIF > 10, recalculating after each removal, until all remaining features have acceptable VIFs.

Protocol 2: Employing Elastic Net for Feature Selection Under Multicollinearity

- Setup: Use the

glmnetpackage in R orscikit-learnin Python. Prepare your CLR-transformed feature matrixXand response vectory. StandardizeX. - Cross-Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation (

cv.glmnet) to find the optimal values for lambda (λ, penalty strength) and alpha (α, where α=1 is LASSO, α=0 is Ridge, 0<α<1 is Elastic Net). - Model Training: Fit the final Elastic Net model with the optimal α and λ. Elastic Net’s blend of L1 (LASSO) and L2 (Ridge) penalty helps select a sparse set of features while stabilizing coefficients for correlated groups.

- Feature Extraction: Retrieve non-zero coefficients from the model. These are the selected features deemed relevant while managing multicollinearity.

Visualizations

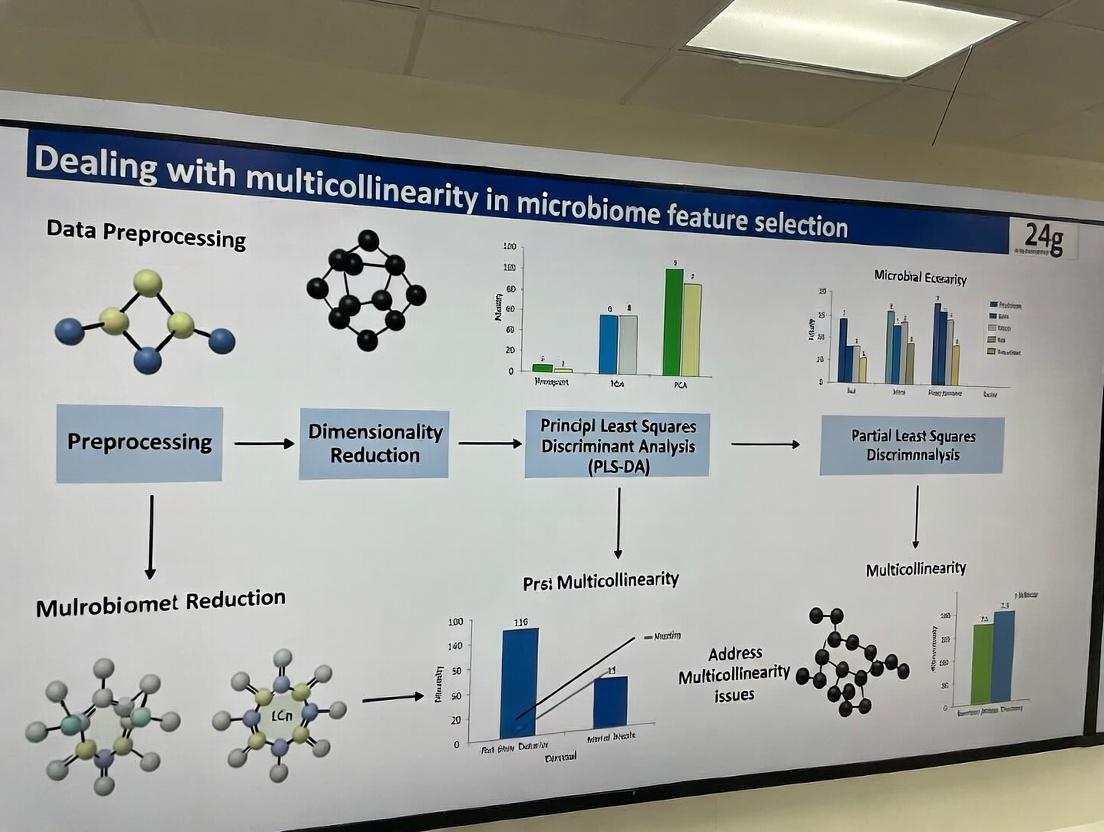

Diagram 1: Impact of Multicollinearity on Feature Selection

Diagram 2: Workflow for Managing Multicollinearity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Multicollinearity Analysis in Microbiome Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transform | Preprocessing method to transform compositional microbiome data into a Euclidean space, reducing spurious correlations and enabling standard statistical analysis. | compositions::clr() in R, skbio.stats.composition.clr in Python. |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Function | A diagnostic function to quantify the severity of multicollinearity for each feature in a regression model. | car::vif() in R, statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence.variance_inflation_factor in Python. |

| Regularized Regression Algorithms | Models with built-in penalties to handle correlated features and perform feature selection simultaneously. | Elastic Net (glmnet in R, sklearn.linear_model.ElasticNet). LASSO (L1 penalty). Ridge (L2 penalty). |

| Stability Selection Framework | A meta-algorithm that combines subsampling with a base feature selector (like LASSO) to identify robustly selected features across perturbations. | c060::stabsel in R, or custom implementation with sklearn. |

| Hierarchical Clustering | Used to identify groups of highly correlated taxa that can be aggregated into a single meta-feature (e.g., by average linkage). | hclust() in R, scipy.cluster.hierarchy in Python, visualized with a correlation heatmap. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Feature Selection with Multicollinearity

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our feature selection for a case-control microbiome study is unstable. Selected taxa change dramatically with small subsampling. What is the core issue and how can we address it?

A: This is a classic symptom of high multicollinearity within high-dimensional, sparse compositional data. Highly correlated microbial features (e.g., due to co-abundance networks or technical artifacts) cause model coefficients to be unstable. To address this:

- Pre-filtering: Remove features with near-zero variance or very high sparsity (>90% zeros) before addressing collinearity.

- Use Regularized Methods: Implement penalized regression (LASSO, Elastic Net) which inherently performs feature selection while handling correlation. Elastic Net (with

alphabetween 0.1 and 0.9) is often preferable to pure LASSO as it can select groups of correlated features. - Stability Selection: Use the stability selection framework with subsampling to identify features robustly selected across many iterations.

Protocol: Stability Selection with Elastic Net

- Perform a CLR or ALR transformation on your ASV/OTU table.

- For 1000 iterations:

- Randomly subsample 80% of the subjects.

- Fit an Elastic Net model (e.g., using

glmnetin R) across a log-spaced lambda penalty sequence. - Record which features have non-zero coefficients.

- Calculate the selection probability for each feature across all iterations.

- Retain features with a selection probability above a defined threshold (e.g., 0.8).

Q2: After using a CLR transformation, our software throws errors about non-positive definite covariance matrices. Why does this happen and what are the solutions?

A: The CLR transform creates a singular covariance matrix because the transformed components sum to zero (they reside in a simplex). This perfect collinearity breaks methods that require matrix inversion (e.g., some implementations of linear discriminant analysis or certain correlation tests).

Solutions:

- Use Appropriate Methods: Choose algorithms designed for compositional data (e.g.,

selbalfor balance selection, ormmvecfor neural network-based selection). - Dimensionality Reduction First: Apply principal components analysis (PCA) on the CLR-transformed data using a robust covariance estimator (like the robust correlation matrix from the

robCompositionsR package), then use PC scores as features. - Switch Transform: Consider the Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR) or a Phylogenetic ILR (PhILR) transformation, which orthonormalizes the data into a Euclidean space, thereby eliminating the perfect collinearity.

Protocol: Robust PCA on CLR-Transformed Data

- Replace zeros with a Bayesian-multiplicative replacement (e.g.,

zCompositions::cmultRepl). - Apply CLR transformation (

compositions::clr). - Compute the robust correlation matrix using

robCompositions::corrwithmethod="spearman". - Perform PCA on this robust correlation matrix.

- Use the first k principal components (which explain >70-80% variance) as de-correlated features for downstream selection.

Q3: We suspect strong multicollinearity is masking truly associated microbial features. How can we diagnose the severity and structure of multicollinearity in our dataset?

A: Standard diagnostics like Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) fail in high-dimensional (p > n) settings. Use these microbiome-adapted diagnostics:

Diagnostic Table:

| Method | Tool/Function | Interpretation | Action Threshold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition Number | kappa() on CLR-transformed, n-filtered data |

Measures global instability. High value indicates ill-conditioning. | > 30 indicates concerning multicollinearity. | ||

| Network Graph of Correlations | SpiecEasi::spiec.easi() or Hmisc::rcorr() |

Visualizes co-abundance clusters (cliques) as correlated feature groups. | Identify dense clusters (modules) with | r | > 0.7. |

| Cross-correlation Matrix Heatmap | corrplot::corrplot() on top n most variable features |

Identifies specific blocks of highly inter-correlated taxa. | Look for large red/blue blocks. |

Protocol: Identifying Correlated Feature Modules

- Filter to the top 500 most variable features (via CLR variance).

- Compute sparse correlation matrix using

SpiecEasi(preferred for compositional bias control) or Spearman rank correlation. - Define a correlation threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.65).

- Input the thresholded adjacency matrix into a network analysis tool like

igraphto find connected components. Each component is a candidate correlated module. - From each module, select a single "representative" feature based on highest connectivity or biological relevance for downstream analysis.

Q4: For drug development targeting a specific pathogen, we need to identify microbial biomarkers that are independently associated with a host response, not just correlated with other microbes. Which feature selection pipeline is recommended?

A: The goal is causal inference, which requires controlling for confounders including microbial interactions. A multi-step pipeline is advised:

Experimental Workflow for Independent Biomarker Discovery

Protocol: De-correlation and Confirmatory Analysis

- Data Preparation: Apply PhILR transformation to obtain orthonormal features (balances).

- Screening: Use a very low-stringency univariate test (p < 0.2) on balances to reduce dimensionality.

- Multivariate Modeling: Fit an Adaptive Elastic Net model on the screened balances. The adaptive weights help in selecting the single strongest signal from a correlated block.

- Confirmatory/Stability Check: Apply De-biased LASSO on the selected features to obtain unbiased coefficient estimates and valid p-values, confirming independent effects.

Research Reagent & Computational Toolkit

| Item Name | Category | Function/Benefit | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM-BC2 (R Package) | Statistical Model | Differential abundance testing that accounts for compositionality and sample-specific biases. Outputs well-calibrated p-values for feature ranking. | Preferred over legacy ANCOM; provides effect sizes. |

| SpiecEasi (R Package) | Network Inference | Infers sparse microbial association networks via Graphical LASSO or MB method. Crucial for visualizing co-abundance structures causing multicollinearity. | Use pulsar for stable lambda selection. |

QIIME 2 / q2-composition (Plugin) |

Bioinformatics Pipeline | Provides robust compositionality-aware tools, including robust Aitchison PCA and gneiss for ILR-based modeling. |

Integrates phylogenetic information via q2-phylogeny. |

selbal / mia (R Packages) |

Feature Selection | selbal identifies predictive balances (log-ratios), inherently managing compositionality. mia provides a tidy ecosystem of microbiome-specific methods. |

selbal is computationally intensive for very high dimensions. |

glmnet (R/Python Package) |

Modeling Engine | Fits LASSO, Ridge, and Elastic Net regression. Essential for regularized feature selection in high-dimensional, collinear settings. | Use cv.glmnet for automatic lambda selection; alpha=0.5 (Elastic Net) often outperforms pure LASSO. |

| RobCompositions (R Package) | Data Transformation | Provides robust methods for imputation, outlier detection, and PCA on compositional data. Critical for preprocessing before modeling. | Use impRZilr for zero replacement. |

| Stability Selection (Framework) | Meta-Algorithm | Wraps around any feature selector (e.g., glmnet) to assess selection frequency under subsampling, increasing reproducibility. |

Implement via c060 R package or custom subsampling loop. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Unstable Feature Selection Results

Symptoms: Large fluctuations in selected features across different subsamples of your microbiome dataset (e.g., bootstraps, cross-validation folds). Model performance metrics (AUC, accuracy) vary widely.

Root Cause: High multicollinearity among microbial taxa (e.g., OTUs, ASVs) due to co-abundance patterns or compositional nature of data. Highly correlated features are interchangeable from the model's perspective.

Steps:

- Calculate Stability: Use the Jaccard index or consistency index to measure overlap between feature sets from 50 bootstrap samples.

- Low Index (<0.6) indicates high instability.

- Check Correlation Matrix: Compute Spearman correlations between top candidate features. A dense cluster of correlations >|0.8| suggests problematic multicollinearity.

- Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Analysis: Fit a preliminary model and calculate VIF for each feature.

- Protocol: For each feature

X_i, run a linear regression withX_ias the target and all other features as predictors. VIF = 1 / (1 - R²). A VIF > 10 indicates severe multicollinearity.

- Protocol: For each feature

Guide 2: Addressing Inflated Variance of Model Coefficients

Symptoms: Wide confidence intervals for coefficient estimates in logistic/linear regression models. Small changes in input data cause large shifts in coefficient magnitude and even sign.

Root Cause: Multicollinearity makes the model matrix nearly singular, dramatically increasing the variance of estimated coefficients.

Steps:

- Visualize Coefficient Confidence: Plot coefficients with 95% confidence intervals from 100 bootstrap iterations. Inflated variance manifests as very wide, often crossing-zero, intervals.

- Apply Regularization: Implement Ridge Regression (L2) or Elastic Net to penalize coefficient size and stabilize estimates.

- Protocol: a. Standardize all features (center & scale). b. Perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=10) over a range of regularization strength (λ) and, for Elastic Net, mixing parameter (α). c. Select λ that minimizes cross-validated mean squared error (MSE). d. Refit model on full data with selected λ/α.

- Use Principal Components Analysis (PCA): Transform correlated original features into uncorrelated principal components (PCs).

Guide 3: Restoring Lost Interpretability

Symptoms: Difficulty assigning biological meaning to selected features. Model outputs a list of 50+ microbial features with no clear biological pathway or theme.

Root Cause: Feature selection methods pick individual correlated predictors, obscuring the underlying cooperative biological structure.

Steps:

- Cluster Features First: Perform hierarchical clustering on the correlation matrix of all features. Select one representative feature (e.g., the most central or abundant) from each cluster for modeling.

- Aggregate into Pathways: Instead of selecting OTUs/ASVs, pre-aggregate data into known microbial metabolic pathways (using tools like HUMAnN3 or MetaCyc).

- Employ Sparse Group Lasso: This method selects groups of correlated features (pre-defined based on taxonomy or pathways) together, maintaining group interpretability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Random Forest model selects different features every time I run it. Is this normal? A: Some variation is expected, but large fluctuations are a red flag. In microbiome data, this is often due to groups of highly correlated taxa. The model arbitrarily picks one from the group. Consider using regularized random forest or clustering correlated features before selection.

Q2: How do I choose between Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net for microbiome data? A: See the table below for a structured comparison.

Q3: I used Lasso and it selected only one feature from a known co-abundant genus. Have I lost information? A: Yes, likely. Lasso's "winner-takes-all" behavior with correlated features is a key drawback. For interpretability, you want the whole group identified. Use Elastic Net with a lower α (e.g., 0.5) or Sparse Group Lasso to encourage group selection.

Q4: Are there stability metrics I should report in my paper? A: Absolutely. Reporting the stability index of your final selected feature set is becoming a best practice. The table below summarizes common metrics.

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Regularization Methods for Multicollinear Microbiome Data

| Method | Handles Multicollinearity? | Feature Selection | Preserves Groups? | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridge (L2) | Yes - stabilizes coefficients | No - keeps all features | Yes (shrinks together) | Prediction priority, all features are potentially relevant |

| Lasso (L1) | Poor - selects one from a group | Yes - creates sparse set | No ("winner-takes-all") | Simple, highly interpretable models when correlations are low |

| Elastic Net | Yes - balance of L1/L2 | Yes - creates sparse set | Can encourage grouping | General purpose for high-dim, correlated microbiome data |

| Sparse Group Lasso | Yes | Yes - at group/feature level | Yes - explicit group structure | Known taxonomic/phylogenetic groups need to be selected or dropped together |

Table 2: Stability Metrics for Feature Selection Results

| Metric | Formula / Description | Interpretation | Threshold for "Stable" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jaccard Index | ∣A∩B∣ / ∣A∪B∣ | Overlap between two feature sets A and B. | > 0.6 over multiple splits |

| Consistency Index (Ic) | (rd - p²) / (p - p²) where r=∣A∩B∣, p=k/p_total | Adjusts for chance agreement between sets of size k. | > 0.8 |

| Average Weight Stability | Correlation of feature weights/importances across subsamples. | Consistency of feature ranking, not just presence. | > 0.7 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Diagnostics for 16S rRNA Amplicon Data

- Input: Normalized (e.g., CLR-transformed) OTU/ASV count table (n samples x p features).

- Procedure:

a. For each microbial feature

iinp: i. Regressfeature_iagainst all otherp-1features using ordinary least squares. ii. Calculate the R-squared (R²) of this regression. iii. ComputeVIF_i = 1 / (1 - R²_i). b. Output a vector of VIF values for allpfeatures. - Decision: Sequentially remove the feature with the highest VIF > 10. Recalculate VIFs for remaining features. Repeat until all VIFs ≤ 10. This yields a non-collinear feature subset.

Protocol: Stability Assessment via Bootstrap Feature Selection

- Input: Full microbiome dataset (X, y).

- Procedure:

a. Generate

B=50bootstrap samples by randomly sampling n rows from (X, y) with replacement. b. Run your chosen feature selection method (e.g., Lasso with CV) on each bootstrap sample to get a selected feature setS_b. c. Calculate the pairwise Jaccard index between all(B*(B-1))/2pairs of sets. d. Report the mean and standard deviation of the pairwise Jaccard indices as the stability measure.

Visualizations

Title: Consequences & Solutions for Multicollinear Feature Selection

Title: VIF Diagnostic Protocol for Microbiome Features

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Microbiome Feature Selection |

|---|---|

scikit-learn (Python) |

Core library providing implementations of Lasso, Ridge, Elastic Net, PCA, and cross-validation utilities for model training and feature selection. |

mixOmics (R) |

Specialized package for multivariate analysis of omics data, includes sparse PLS-DA and DIABLO for integrated, stable feature selection on correlated data. |

glmnet (R)/sklearn.linear_model |

Highly optimized routines for fitting Lasso and Elastic Net models with cross-validation, essential for high-dimensional microbiome data. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transform | A normalization technique for compositional microbiome data that mitigates spurious correlations, a prerequisite for stable selection. |

pingouin (Python)/corrplot (R) |

Libraries for calculating and visualizing correlation matrices and Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) to diagnose multicollinearity. |

| QIIME 2 / PICRUSt2 / HUMAnN3 | Bioinformatic pipelines for processing raw sequences and inferring functional pathway abundances, enabling feature selection at the pathway level. |

Stability Selection Library (e.g., stabs in R) |

Implements the stability selection framework, which combines subsampling with selection algorithms to improve reliability. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I differentiate between a true biological co-abundance signal and a technical artifact introduced during sequencing?

- Answer: True co-abundance often persists across different bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., DADA2, Deblur) and normalization methods (e.g., CSS, TSS, log-ratio). Technical artifacts, such as those from index hopping or batch effects, are often correlated with specific sequencing runs or sample preparation batches. Conduct a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) colored by batch ID. If the first principal components separate by batch, batch correction (e.g., via ComBat or percentile normalization) is required before interpreting co-abundance.

FAQ 2: My feature selection model fails due to high multicollinearity among microbial taxa. What is the likely source and how can I address it?

- Answer: The primary sources are Functional Redundancy (different taxa performing the same function leading to correlated abundances) and Co-abundance Networks (ecological guilds or cross-feeding interactions). To address this:

- Aggregate Features: Group taxa at a higher taxonomic level (e.g., genus instead of OTU/ASV) or into functional guilds using databases like METACYC or KEGG.

- Use Robust Methods: Employ feature selection methods designed for collinear data, such as:

- Elastic Net: A regularized regression that combines L1 and L2 penalties.

- MIC: Maximal Information Coefficient for non-linear dependencies.

- HSIC-Lasso: Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion Lasso for non-linear, high-dimensional data.

- Leverage Networks: Use SparCC or SPIEC-EASI to construct networks and select hub features rather than all correlated members.

FAQ 3: I suspect functional redundancy is masking key biomarkers in my case-control study. How can I test for this and refine my analysis?

- Answer: Perform functional profiling (e.g., with PICRUSt2, Tax4Fun2, or HUMAnN3) on your metagenomic or 16S data. Then, test for pathway-level differential abundance using tools like MaAsLin2 or LEFSe. If pathways are significant while individual taxa are not, functional redundancy is likely. Feature selection should then be performed on pathway abundances, or taxa can be grouped by their contribution to key pathways.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Technical Artifacts in 16S rRNA Sequencing and Their Mitigation

| Artifact Source | Effect on Data (Multicollinearity) | Diagnostic Test | Mitigation Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Effects | Introduces false correlations within batches | PERMANOVA on batch metadata | Apply ComBat-seq or SVA, include batch as covariate in models. |

| Index Hopping | Inflates rare taxa counts, creates spurious cross-sample links | Check for reads in negative controls; high similarity in heterogenous samples. | Use unique dual indexing (UDI), bioinformatic filters (e.g., decontam R package). |

| PCR Amplification Bias | Skews abundance ratios, causing false positive correlations | Use of technical replicates; spike-in controls. | Employ a low-cycle PCR protocol, use PCR-free library prep if possible. |

| Variable Sequencing Depth | Induces compositionality, spurious correlations | Rarefaction curve analysis; comparison of library sizes. | Use Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) methods like CLR transformation with a prior. |

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Handling Multicollinearity from Co-abundance

| Method | Type | Handles Non-linearity? | Key Advantage for Microbiome Data | Software/Package |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Net | Regularized Regression | No | Selects groups of correlated features, good for high-dimensional data. | glmnet (R), scikit-learn (Python) |

| SparCC | Correlation Inference | No | Accounts for compositionality, infers robust correlations. | SpiecEasi (R), native Python version |

| HSIC-Lasso | Kernel-based Selection | Yes | Captures complex, non-linear dependencies between taxa. | hsic-lasso (Python) |

| Graphical Lasso | Network Inference | No | Infers conditional dependencies (partial correlations), controlling for indirect effects. | SpiecEasi (R), skggm (Python) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying and Correcting for Batch-Induced Technical Artifacts

Objective: To diagnose and statistically remove batch effects that induce false multicollinearity. Materials: Normalized feature table (OTU/ASV), metadata with batch ID, R statistical software. Procedure:

- Diagnosis: Perform a PERMANOVA (adonis2 function in

veganR package) using a Bray-Curtis distance matrix with 'Batch' as the predictor. A significant p-value (p < 0.05) indicates a batch effect. - Visualization: Generate a PCA plot (using the

prcompfunction) of the CLR-transformed data, colored by batch. - Correction: Apply the

ComBat_seqfunction from thesvaR package. Input the raw count matrix, batch ID, and (if applicable) a model matrix for biological groups you wish to preserve. - Verification: Re-run the PERMANOVA and PCA on the corrected data. The batch effect should no longer be significant or visually apparent.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Co-abundance Network for Feature Grouping

Objective: To group collinear features into network modules for aggregated analysis.

Materials: Filtered, compositional-normalized (e.g., CLR) abundance table. R with SpiecEasi and igraph packages.

Procedure:

- Network Inference: Run the

spiec.easi()function using the 'mb' (Meinshausen-Bühlmann) or 'glasso' method. Use a reasonably low lambda.min.ratio (e.g., 1e-3) for a dense network. - Network Creation: Convert the output adjacency matrix to an

igraphobject usingadj2igraph(). - Module Detection: Perform community detection using the clusterfastgreedy() function to identify modules of highly interconnected taxa.

- Feature Aggregation: For each sample, sum the CLR-transformed abundances of all taxa within a given module to create a module eigentaxon (ME) value. Use these MEs as new, less collinear features in downstream models.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Diagnostic Workflow for Technical Artifact Identification

Diagram Title: Three Strategies to Overcome Functional Redundancy

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent & Computational Solutions Table

| Item | Function in Context of Multicollinearity | Example/Product |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Provides a known mock community to diagnose technical artifacts (e.g., PCR/sequencing bias) that can cause spurious correlations. | Zymo Research, D6300 |

| PhiX Control v3 | Improves base calling accuracy on Illumina platforms, reducing sequence errors that can create artificial OTUs/ASVs and false correlations. | Illumina, FC-110-3001 |

| UNIQUE DUAL INDEXES (UDIs) | Minimizes index hopping (sample cross-talk), a major source of false-positive inter-sample correlations. | Illumina Nextera UD Indexes |

| PICRUSt2 Software | Predicts metagenome functional content from 16S data, allowing analysis at the less-redundant pathway level instead of collinear taxa. | BioBakery Suite |

| SpiecEasi R Package | Infers microbial ecological networks (co-abundance) from compositional data, essential for identifying hub features within correlated guilds. | CRAN / GitHub |

| glmnet R Package | Performs Elastic Net regression, a key method for feature selection in the presence of high multicollinearity. | CRAN |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: I've calculated VIFs for my 500 ASVs, and many are extremely high (>100). What is the most practical first step to address this?

A1: High VIFs (>10 is a common threshold, but >5 can be concerning) indicate severe multicollinearity. Your first step should be to reduce feature dimensionality before applying VIF.

- Action: Perform an initial variance-based filter. Remove ASVs with near-zero variance or very low prevalence (e.g., present in <10% of samples). Then, consider aggregating phylogenetically related ASVs to the Genus or Family level. Recalculate VIF on this reduced set. This often resolves the most extreme issues.

Q2: When I compute the correlation matrix for my OTU table, it's massive and visually uninterpretable. How can I effectively identify problematic collinear groups?

A2: A full correlation matrix for hundreds of OTUs is not useful visually.

- Action: Use your correlation matrix programmatically. Set a high correlation threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.9). Write a script to identify clusters of features where each member is highly correlated with at least one other member. These clusters are candidates for removal or aggregation. Tools like

findCorrelationin R'scaretpackage automate this.

Q3: My condition index is above the critical value (often 30), but VIFs for individual ASVs are moderate. Which metric should I trust?

A3: This discrepancy is informative. A high condition index indicates a dependency among three or more features, not just a pair. Moderate VIFs can miss these complex multicollinearities.

- Action: Trust the condition index as a red flag. Investigate the variance decomposition proportions associated with the high-index dimension. Features with high proportions (>0.5) on that dimension form the problematic collinear group. You may need to drop one or more features from this specific group.

Q4: I need to select a non-collinear set of features for a predictive model (like LASSO or random forest). Should I use VIF, correlation, or condition indices?

A4: Use a sequential approach:

- Correlation Matrix First: Identify and remove one feature from each pair with |r| > 0.95 (prioritizing the feature with lower biological relevance or mean abundance).

- VIF Second: On the remaining features, iteratively remove the feature with the highest VIF > 10 until all VIFs are acceptable.

- Condition Index Check: For final diagnostic, compute the condition index of the selected feature set to ensure no hidden multicollinearity remains.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Multicollinearity in Microbiome Features

Objective: To diagnose and mitigate multicollinearity among microbial features (OTUs/ASVs) prior to statistical modeling for feature selection.

Materials & Software:

- R (v4.0+) or Python 3.8+

- R Packages:

car,vegan,caret,corrplot/ Python Libraries:statsmodels,scikit-learn,pandas,numpy,seaborn - Input Data: Normalized (e.g., CSS, CLR) OTU/ASV abundance table (samples x features).

Methodology:

1. Data Preprocessing:

- Filter out low-abundance features (e.g., those with a total count < 10 across all samples).

- Apply a variance-stabilizing transformation (e.g., Center Log-Ratio - CLR). Note: CLR on compositional data requires care with zeros.

2. Calculate Pairwise Correlation Matrix:

- Compute Spearman or Pearson correlations between all feature pairs.

- Code (R):

cor_matrix <- cor(clr_table, method="spearman") - Visualize a subset (e.g., top 50 most variable ASVs) using a heatmap.

3. Compute Variance Inflation Factors (VIF):

- Treat each feature as a response variable regressed against all others.

- VIF = 1 / (1 - R²). Typically calculated using a linear model, but for compositional data, a GLM with appropriate distribution may be considered.

- Code (R using

car):

4. Calculate Condition Indices and Variance Decomposition Proportions:

- Perform a singular value decomposition (SVD) on the design matrix (your feature table).

- Condition Index: √(λmax / λi) for each singular value (λ_i).

- Examine the matrix of variance decomposition proportions to see which features contribute to each high condition index.

- Code (R):

5. Mitigation Actions Based on Results:

- Feature Removal: From highly correlated pairs (from Step 2) or groups (from Step 4), remove the less informative feature.

- Feature Aggregation: Aggregate taxonomically related features to a higher rank.

- Use Regularized Models: Proceed with models like LASSO or Ridge regression that can handle some multicollinearity.

Table 1: Interpretation Guidelines for Multicollinearity Diagnostics

| Diagnostic Tool | Threshold for Concern | What it Identifies | Primary Limitation for Microbiome Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise Correlation | r | > 0.8 - 0.9 | Linear dependence between two features. | Misses complex multi-feature collinearity. | |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | VIF > 5 (Moderate) VIF > 10 (Severe) | Inflation of a feature's coefficient variance due to collinearity. | Computationally heavy for 1000s of ASVs; assumes linear relationships. | ||

| Condition Index (CI) | CI > 10 (Moderate) CI > 30 (Severe) | Overall instability of the model matrix; identifies multi-feature dependencies. | Requires careful inspection of variance proportions to pinpoint features. |

Table 2: Example Output from a Multicollinearity Diagnostic on a Simulated ASV Dataset (n=50 top ASVs)

| ASV ID | Taxonomic Assignment (Genus) | VIF | Max Correlation with another ASV | In High CI Cluster? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASV_001 | Bacteroides | 12.7 | 0.94 (with ASV_005) | Yes |

| ASV_005 | Bacteroides | 14.3 | 0.94 (with ASV_001) | Yes |

| ASV_032 | Faecalibacterium | 3.2 | 0.41 (with ASV_040) | No |

| ASV_087 | Akkermansia | 1.8 | -0.32 (with ASV_012) | No |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Condition Index | 35.6 (Dimension 15) |

Visualization of Workflows

Multicollinearity Diagnosis and Mitigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Analysis | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

R with car & vegan packages |

Core statistical computing. car provides vif() function. vegan handles ecological data. |

Essential open-source toolkit. Ensure packages are updated. |

Python with statsmodels & scikit-learn |

Alternative open-source platform. statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence.variance_inflation_factor calculates VIF. |

Preferred for integration into machine learning pipelines. |

| CLR Transformation Code | Applies a compositional transform to mitigate the unit-sum constraint of relative abundance data. | Requires imputation of zeros (e.g., using zCompositions::cmultRepl() in R). |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster Access | Enables correlation/VIF calculation on large feature sets (e.g., >5,000 ASVs) in a reasonable time. | Cloud computing services (AWS, GCP) are a viable alternative. |

| Script for Cluster Identification | Custom script to identify groups of correlated features from a correlation matrix above a threshold. | Reduces manual inspection of large matrices. Can use graph-based clustering. |

From Theory to Pipelines: Effective Methods to Mitigate Multicollinearity in Your Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My LASSO model in R (glmnet) selects an unexpectedly high number of features (or none) from my microbiome OTU table, even when I vary alpha. What could be wrong?

A: This is frequently caused by improper data scaling. Microbiome abundance data (e.g., OTU counts, relative abundances) often have vastly different variances across features. LASSO is sensitive to feature scale—features with larger variance are unfairly penalized. Solution: Standardize all predictor features (X matrix) to have zero mean and unit variance before model fitting. Use glmnet's standardize=TRUE argument (default) or manually scale. Do not standardize your outcome variable for count-based models.

Q2: When applying Elastic Net, how do I practically choose the optimal alpha (mixing) and lambda (penalty) parameters for a sparse microbiome model? A: Use a nested cross-validation approach to prevent data leakage and overfitting.

- Protocol: Create an outer k-fold (e.g., 5-fold) CV loop for performance estimation. Within each training fold, run an inner CV loop (e.g., 10-fold) over a grid of alpha (e.g., seq(0, 1, by=0.1)) and lambda values. Select the (alpha, lambda) pair that minimizes the deviance or mean squared error in the inner CV. Refit the model on the entire outer training set with these parameters and evaluate on the outer test fold. Repeat for all outer folds.

- Common Pitfall: Using the same CV for both hyperparameter tuning and final performance reporting inflates results.

Q3: I'm getting convergence warnings or extremely slow performance when fitting a sparse regression model on my large metagenomic feature set (p >> n). What can I do? A: High-dimensional data exacerbates computational demands.

- Increase Iterations: For

glmnet, increase themaxitparameter (e.g., to 1e6). - Check Preprocessing: Ensure you are using a sparse matrix format (

Matrixpackage in R) if your data has many zeros. - Feature Pre-screening: Consider a univariate pre-filter (e.g., variance filtering or correlation with outcome) to reduce dimensionality before applying LASSO/Elastic Net, though this risks removing synergistic signals.

- Algorithm Choice: Use the

gammaargument inglmnetto implement the Adaptive LASSO for potentially more stable selection.

Q4: How do I interpret the coefficients from a fitted Elastic Net model for microbiome feature selection, given the data is compositional? A: Direct interpretation as effect size is problematic. Due to the compositional nature of microbiome data (features sum to a constant), regularization can arbitrarily shift coefficient magnitude between correlated taxa. Best Practice: Focus on feature selection stability, not just coefficient magnitude. Use stability selection or repeated subsampling to identify features consistently selected across multiple model fits. Report the selection frequency for each taxon.

Q5: The selected features from my LASSO model vary dramatically with a small change in the random seed for data splitting. Is the model useless? A: Not useless, but it indicates low selection stability, common in high-dimensional, correlated microbiome data. Solution: Implement Stability Selection.

- Protocol: Subsample your data (e.g., 50% of samples) without replacement 100-1000 times. For each subsample, run LASSO/Elastic Net across a range of lambda values (not just one optimal). Record which features are selected. Calculate each feature's selection probability (proportion of subsamples where it was selected). Features with probability above a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 0.8) are considered stably selected. This mitigates the volatility inherent in single-model fits.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Regularization Techniques for Microbiome Feature Selection

| Technique | R/Python Function | Key Hyperparameter(s) | Pros for Microbiome Data | Cons for Microbiome Data | Typical Use Case in Microbiome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO (L1) | glmnet(..., alpha=1) |

Lambda (λ) | Forces exact coefficients to zero, yielding a sparse, interpretable model. | Selects only one feature from a group of highly correlated (collinear) taxa. | Initial screening for strong, univariate-associated biomarkers. |

| Ridge (L2) | glmnet(..., alpha=0) |

Lambda (λ) | Handles multicollinearity well; keeps all features, shrinking coefficients. | Does not perform feature selection; all features remain in model. | Prediction-focused tasks where feature interpretation is secondary. |

| Elastic Net | glmnet(..., alpha=β) |

Alpha (α), Lambda (λ) | Compromise: selects groups of correlated taxa while encouraging sparsity. | Introduces a second hyperparameter (α) to tune. | General-purpose feature selection when multicollinearity is suspected. |

| Stability Selection | c060::stabsel or custom |

Selection Probability Threshold | Identifies features stable across subsamples, reducing false positives. | Computationally intensive. | Validating and reporting robust microbial signatures from sparse models. |

Table 2: Example Hyperparameter Grid for Nested CV (Elastic Net on 16S Data)

| Parameter | Search Values | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha (α) | seq(0, 1, length.out = 11) |

0=Ridge, 1=LASSO, intermediate=Elastic Net. |

| Lambda (λ) | 10^seq(-3, 2, length=100) |

Penalty strength; typically searched on log scale. |

| Inner CV Folds | 10 | For hyperparameter tuning within training set. |

| Outer CV Folds | 5 | For final unbiased performance estimation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Pipeline for Sparse Regression on Relative Abundance Data

- Input: OTU/ASV table (samples x taxa), clinical metadata (outcome vector).

- Preprocessing: Filter low-prevalence taxa (<10% of samples). Apply a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation or variance-stabilizing transformation (VST) to address compositionality. Standardize all transformed features (mean=0, SD=1).

- Model Fitting: Use

cv.glmnetwithfamily="gaussian"(continuous outcome) or"binomial"(binary outcome). Setalphaas desired or tune. - Tuning: Let

cv.glmnetperform 10-fold CV to find the optimallambda(lambda.1seis recommended for sparser models). - Feature Extraction: Extract non-zero coefficients from the model fit at the optimal

lambda. - Validation: Apply stability selection (see Protocol 2) or validate on a held-out cohort.

Protocol 2: Stability Selection Implementation

- For

bin 1 toB(e.g.,B=500):- Randomly subsample

N/2samples without replacement. - Run

glmneton the subsample across a range of lambda values (e.g.,lambda.1se * c(0.5, 1, 2)). - Record the set of selected features

S_b(lambda)for each lambda.

- Randomly subsample

- For each feature

j, compute its selection probability:π_j = max_{λ} ( #{b : j ∈ S_b(λ)} / B ). - Select features with

π_j≥π_thr(e.g., 0.8). The threshold can be derived to control per-family error rate (PFER).

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Sparse Regression Workflow for Microbiome Data

Title: Geometry of LASSO (Diamond) vs Ridge (Circle) Constraints

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Regularization Analysis of Microbiome Data |

|---|---|

R glmnet package |

Core engine for fitting LASSO, Ridge, and Elastic Net regression models efficiently via coordinate descent. |

compositions R package |

Provides the clr() function for Centered Log-Ratio transformation, a key method to handle compositional data before regularization. |

Matrix R package |

Enables the use of sparse matrix objects to store and compute on high-dimensional, zero-inflated OTU tables, improving speed and memory usage. |

c060 or stabs R packages |

Implements stability selection methods to assess the reliability of features selected by penalized models. |

mixOmics R package |

Offers sparse multivariate methods (e.g., sPLS-DA) tailored for omics data, providing an alternative regularization framework. |

Python scikit-learn |

Provides ElasticNet, Lasso, and Ridge classes, along with extensive CV tools, for a Python-based workflow. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transform | Not a reagent, but a critical mathematical "tool" that transforms compositional data to a Euclidean space, making standard regularization applicable. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster Access | Often necessary for running repeated subsampling (stability selection) on large metagenomic feature sets (>10k taxa). |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

General Troubleshooting for Dimensionality Reduction

Q1: My PCA components explain a very low percentage of variance in my microbiome data. What could be wrong? A: This is often caused by high-frequency noise or excessive sparsity. First, apply appropriate filtering to remove low-abundance or low-variance features. Consider using a variance-stabilizing transformation (e.g., centered log-ratio for compositional data) before PCA. If the issue persists, the underlying data structure may be non-linear, and non-linear methods (e.g., UMAP, t-SNE) might be more appropriate, though they are not directly related to multicollinearity mitigation.

Q2: When applying PLS for feature selection, the model is severely overfitting. How can I improve its generalizability? A: Overfitting in PLS typically stems from using too many latent components. Use cross-validation (e.g., 10-fold) to determine the optimal number of components that minimizes the prediction error. Additionally, ensure your response variable (e.g., disease status) is not confounded by batch effects. Implement a permutation test to assess the significance of your model's performance.

Q3: How do I handle many zero values in my OTU/ASV table before running phylogenetically-informed PCA?

A: Phylogenetically-informed methods like Phylo-PCA are sensitive to the compositional nature of data. Do not use simple mean imputation for zeros. Apply a Bayesian or multiplicative replacement method designed for compositional data (e.g., from the zCompositions R package). Alternatively, use a phylogenetic inner product matrix that accounts for sparsity.

Q4: I am getting inconsistent results from PLS-DA on different subsets of my microbiome cohort. What steps should I take? A: Inconsistency can arise from cohort stratification or technical variation.

- Check for Confounders: Test for associations between your PLS components and metadata like age, BMI, or batch.

- Normalization: Ensure consistent normalization (e.g., CSS, TSS) across all subsets.

- Stability Analysis: Perform a stability selection procedure by running PLS-DA on multiple bootstrapped samples and selecting features that appear frequently.

Troubleshooting Phylogenetically-Informed Variants

Q5: When running Phylo-PCA, the software fails due to memory issues with a large phylogeny. How can I resolve this? A: The covariance matrix based on a large tree is computationally intensive.

- Option 1: Use a filtered, smaller set of representative taxa (e.g., at the genus level) for the initial analysis.

- Option 2: Employ algorithms that work directly with the tree structure without computing the full covariance matrix, if available in the software.

- Option 3: Increase memory allocation for your computing environment, or switch to a high-performance computing cluster.

Q6: What is the main practical difference between Phylo-PCA and standard PCA for microbiome feature selection? A: Standard PCA treats each microbial taxon as an independent feature, while Phylo-PCA incorporates evolutionary relationships. Consequently, Phylo-PCA will group phylogenetically similar taxa together in its components, even if their abundances are not directly correlated. This often leads to more biologically interpretable axes of variation (e.g., separating broad clades) and reduces the redundancy caused by phylogenetic correlation.

Q7: Can phylogenetically-informed PLS (Phylo-PLS) be used for regression with a continuous outcome, like a metabolite concentration? A: Yes. The phylogenetic constraint can be integrated into the PLS framework by using the phylogenetic covariance matrix to define a penalty term or by transforming the OTU table using phylogenetic eigenvectors. This guides the model to consider evolutionary relationships when finding components that maximize covariance with the continuous outcome, potentially leading to more robust biomarkers.

Table 1: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Multicollinear Microbiome Data

| Method | Acronym | Key Purpose | Handles Multicollinearity? | Incorporates Phylogeny? | Output Useful for Feature Selection? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis | PCA | Variance maximization, noise reduction | Yes (creates orthogonal components) | No | Indirect (via component loadings) |

| Phylogenetic PCA | Phylo-PCA/PCA | Variance maximization under phylogenetic constraint | Yes | Yes | Indirect, phylogenetically grouped |

| Partial Least Squares | PLS (or PLS-DA) | Maximize covariance with an outcome | Yes (extracts latent components) | No | Yes (via variable importance) |

| Phylogenetically-Informed PLS | Phylo-PLS | Maximize covariance with outcome under constraint | Yes | Yes | Yes, with phylogenetic guidance |

Table 2: Typical Workflow Parameters and Recommendations

| Step | Parameter/Choice | Standard PCA/PLS Recommendation | Phylogenetically-Informed Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-processing | Zero Handling | Bayesian/multiplicative imputation | Phylogeny-aware imputation or ignore | Preserves compositionality, phylogeny structure |

| Transformation | Normalization | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | CLR or PhILR (Phylogenetic Isometric Log-Ratio) | Achieves Euclidean geometry; PhILR creates orthogonal parts |

| Model Tuning | Component Number | Cross-validation, scree plot | Cross-validation, phylogenetic signal check | Prevents overfitting, selects meaningful axes |

| Validation | Model Significance | Permutation test (for PLS-DA) | Phylogenetic permutation (tip-shuffling) | Ensures results are not due to chance or tree structure alone |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard PCA for Microbiome Data Pre-processing

Objective: Reduce dimensionality and mitigate multicollinearity prior to downstream feature selection or modeling.

- Input: Filtered OTU/ASV count table (samples x features).

- Normalization: Convert counts to relative abundances (Total Sum Scaling).

- Transformation: Apply Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation using a geometric mean pseudocount.

- Center & Scale: Center the data (mean=0) and scale to unit variance (optional, but recommended for abundance ranges).

- Compute PCA: Perform singular value decomposition (SVD) on the preprocessed matrix.

- Output: Use component scores (for visualization) and loadings (to identify contributing taxa).

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic PCA (Phylo-PCA) Implementation

Objective: Perform PCA on microbiome data while incorporating evolutionary relationships to produce phylogenetically structured components.

- Prerequisites: OTU table and a corresponding rooted phylogenetic tree for all taxa.

- Calculate Covariance: Compute the expected covariance matrix of trait evolution under a Brownian motion model using the phylogenetic tree. This creates matrix C.

- Transform Data: Whiten the CLR-transformed OTU data using the inverse square root of C. This step decorrelates the data according to the phylogeny.

- Apply Standard PCA: Perform standard PCA on the phylogenetically transformed data.

- Interpretation: The resulting principal components represent major axes of phylogenetically independent variation.

Protocol 3: PLS-DA for Discriminatory Feature Selection

Objective: Identify microbial features most predictive of a categorical outcome (e.g., disease vs. healthy).

- Input: Preprocessed (CLR) feature matrix X and a dummy-coded response matrix Y.

- Cross-Validation: Set up k-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal number of latent components (ncomp).

- Model Training: Fit a PLS model (e.g., using SIMPLS algorithm) to find components that maximize covariance between X and Y.

- Variable Importance: Calculate Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores for each feature.

- Feature Selection: Retain features with VIP score > 1.0 (common threshold) as candidates for biomarkers.

- Validation: Assess model performance and significance via permutation testing on the cross-validated accuracy.

Visualizations

Title: Standard PCA Pre-processing Workflow

Title: PLS Model Validation & Troubleshooting Logic

Title: Phylogenetic PCA (Phylo-PCA) Procedure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Tools for Dimensionality Reduction in Microbiome Research

| Item | Function & Relevance | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA / ITS Sequencing Data | Raw microbial community data. The foundational input. | Must be processed (DADA2, QIIME2, mothur) into an OTU/ASV table. |

| Reference Phylogenetic Tree | Required for phylogenetically-informed variants. | Generated from sequences using tools like FastTree, RAxML, or sourced from GTDB. |

| CLR-Transformed Data Matrix | A compositionally appropriate input for PCA/PLS. | Created using the compositions (R) or scikit-bio (Python) packages. |

| Phylogenetic Covariance Matrix (C) | Encodes expected evolutionary relationships. | Calculated from the tree using ape (R) picante (R) or skbio (Python). |

| VIP Score Table | Output from PLS-DA for feature selection. Ranks taxa by predictive importance. | Features with VIP > 1.0 are considered important contributors to the model. |

| Permutation Test p-value | Validates PLS-DA model significance against random chance. | A p-value < 0.05 indicates the model's discrimination is statistically significant. |

| Cross-Validation Error Plot | Diagnostic plot to determine optimal number of latent components (for PLS/PLS-DA). | The component number at the minimum error is chosen to avoid overfitting. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting and FAQs

Q1: My co-occurrence network is too dense (fully connected or too many edges), making it impossible to identify meaningful modules or representative taxa. What went wrong? A1: This typically indicates an inappropriate correlation threshold or method for network inference.

- Primary Check: Re-examine your correlation measure and significance testing. For microbiome count data, robust measures like SparCC or SPIEC-EASI (via

SpiecEasipackage) are preferred over Pearson/Spearman to mitigate compositionality effects. Ensure you are applying a p-value correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg). - Solution Protocol: Rerun network inference with stricter thresholds.

- Calculate pairwise associations using a compositionally aware method.

- Apply a dual threshold: retain only edges with

|correlation| > 0.3(or a higher, data-driven cutoff) and an adjusted p-value < 0.01. - Visualize the network with the new adjacency matrix. Iteratively adjust thresholds until the network has a clear modular structure.

Q2: After selecting a "representative taxon" from a network module, I find its abundance is very low. Is it still a valid representative for downstream analysis (e.g., as a predictor in a regression model)? A2: Potentially, but with caution. A low-abundance, highly connected "hub" taxon can be a valid biological proxy for its module's state. However, it may introduce technical noise.

- Actionable Steps:

- Validate Correlation: Ensure the representative taxon's abundance profile is highly correlated (e.g., Spearman Ï > 0.8) with the first principal component (PC1) of its entire module's abundance matrix. This confirms it captures the module's variance.

- Consider Aggregation: As an alternative, use the module's PC1 score (module eigentaxon) as the representative feature. This is often more robust.

- Log-Transform: For regression, apply a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation to the representative taxon's abundance to stabilize variance.

Q3: How do I formally test if network-based selection reduces multicollinearity compared to selecting all taxa or using other filter methods? A3: You can quantify multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Compare VIF scores across different feature sets.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Create three feature sets for the same samples: Set A: All taxa (CLR-transformed). Set B: Top N taxa by variance or abundance. Set C: Representative taxa (one per network module, CLR-transformed).

- For each set, fit a multiple linear regression model (with a dummy outcome if needed, or a relevant clinical variable).

- Calculate the VIF for each feature in each model.

- Compare the distribution of VIFs. Successful network-based selection (Set C) should yield a set with a lower mean/median VIF and no features with VIF > 5-10.

Q4: My network modules are unstable—they change completely when I subset my samples. How can I improve robustness? A4: This suggests your network structure is not consistent across the population. Implement bootstrap or subsampling validation.

- Robustness Testing Protocol:

- Generate 100 random subsamples of your data (e.g., 80% of samples without replacement).

- For each subsample, reconstruct the co-occurrence network and identify modules.

- Use a consensus clustering approach (e.g., in R

WGCNApackage functions likemodulePreservation) to assess how often taxa are grouped together. - Only select representative taxa from modules that appear in >70% of the subsamples.

Q5: What is the step-by-step workflow from raw ASV table to final set of representative taxa? A5: Follow this detailed methodology.

| Step | Procedure | Tool/Function (R) | Purpose | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Preprocessing | Filter low-abundance taxa (<0.01% prevalence). | phyloseq::filter_taxa |

Reduce noise & sparsity. | prune_taxa(taxa_sums(x) > X, x) |

| 2. Transformation | Apply Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transform. | compositions::clr |

Handle compositionality. | Use pseudocount if zeros present. |

| 3. Network Inference | Calculate robust correlations. | SpiecEasi::spiec.easi |

Build sparse graph. | method='mb', lambda.min.ratio=1e-2 |

| 4. Network Construction | Create undirected graph from adjacency matrix. | igraph::graph_from_adjacency_matrix |

Object for analysis. | mode='undirected', weighted=TRUE |

| 5. Module Detection | Identify clusters (modules). | igraph::cluster_fast_greedy |

Find taxa communities. | Use edge weights. |

| 6. Representative Selection | For each module, select taxon with highest connectivity (hub). | igraph::degree or correlate with module eigentaxon (PC1). |

Choose proxy taxon. | Choose method: Intra-modular connectivity. |

| 7. Validation | Calculate VIF for selected taxa set. | car::vif on a linear model. |

Quantify multicollinearity reduction. | VIF threshold < 5 or 10. |

Representative Taxa Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Network-Based Selection |

|---|---|

| R with phyloseq | Core package for microbiome data object management, preprocessing, and integration with analysis tools. |

| SpiecEasi Package | Provides the spiec.easi() function for inferring sparse microbial association networks from compositional data. |

| igraph Package | Essential library for all network analysis steps: graph construction, community detection, and centrality calculation. |

| compositions Package | Offers the clr() function for proper Centered Log-Ratio transformation of compositional count data. |

| WGCNA Package | Although designed for gene networks, its functions for consensus module detection and preservation statistics are highly adaptable for microbiome networks. |

| car Package | Contains the vif() function to calculate Variance Inflation Factors, critical for validating the reduction of multicollinearity. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Network inference (bootstrapping, SPIEC-EASI) is computationally intensive; HPC access is often necessary for robust analysis. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My SELBAL algorithm fails to converge or finds an empty balance. What are the likely causes and solutions?

A: This is often due to data sparsity or inappropriate initialization.

- Cause: Excessive zeros in your ASV/OTU table can prevent the algorithm from identifying a meaningful balance between two groups of taxa.

- Solution: Apply a prudent prevalence filter (e.g., retain features present in >10% of samples) before running SELBAL. Ensure your

num.iterandnum.stepparameters are sufficiently high (e.g., 1000 and 5, respectively). Consider using the provided initialization vectors if you have prior biological knowledge.

Q2: ANCOM-BC reports many differentially abundant taxa, but the W-statistic seems inflated. How do I validate these findings?

A: The W-statistic in ANCOM-BC is a test statistic, not an effect size. Overly broad findings may indicate unaccounted-for confounding.

- Cause: The model's

grouporformulavariable may be correlated with other metadata (e.g., batch, age) not included in the model, leading to false positives. - Solution: Include all relevant technical and biological covariates in the

formulaargument (e.g.,~ batch + age + group). Always check thebeta(estimated log fold change) andse(standard error) columns to assess the magnitude and precision of the effect, not just the p-value.

Q3: When using a compositionally-aware method like ALDEx2 or a CLR-based model, how should I handle samples with zero counts for a feature of interest?

A: These methods require a prior or pseudo-count to handle zeros for the log-ratio transformation.

- Cause: The Geometric Mean (G) in the denominator of the CLR is zero if any feature is zero in a sample, making the ratio undefined.

- Solution: Use the method-specific recommended approach. For ALDEx2, use the

include.sample.sum=FALSEargument and its built-in Monte-Carlo sampling from the Dirichlet distribution. For general CLR, a centered log-ratio (CLR) with a prior (e.g., Bayesian-multiplicative replacement as in thezCompositionsR package) is superior to a simple uniform pseudo-count.

Q4: My cross-sectional study has high multicollinearity among microbial features. Which method is most robust for feature selection in this context?

A: In a high-multicollinearity context within compositional data, your primary tools are regularization and balance-based approaches.

- Recommendation: Consider SELBAL or mmvec if your goal is to find co-abundant groups predictive of a phenotype. For identifying individual, differentially abundant features, use ANCOM-BC (which uses a linear model framework) or a zero-inflated Gaussian Mixture Model like metagenomeSeq's fitFeatureModel, as they are less sensitive to inter-feature correlation than methods assuming feature independence.

Q5: How do I choose between correlation-based networks (like SparCC) and balance-based approaches (like SELBAL) for understanding microbial associations?

A: The choice depends on your biological question.

- SELBAL/Quasi-balances: Best for supervised analysis—finding a microbial driver (a balance) strongly associated with a specific outcome (e.g., disease state, drug response). It reduces multicollinearity by construction.

- SparCC/CCLasso: Best for unsupervised inference of global microbial interaction networks. They estimate all pairwise correlations in a compositionally-robust manner, useful for generating ecological hypotheses.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Running a SELBAL Analysis for Biomarker Discovery

- Input Preparation: Format your data as a matrix (samples x taxa) and a vector for the outcome variable.

- Preprocessing: Apply a prevalence filter (e.g., >10%) and a variance filter. Do NOT center log-ratio (CLR) transform the data.

- Execution: Use the

selbal()function with key arguments:y: The outcome variable vector.x: The preprocessed taxa matrix.num.iter: Set to 1000.num.step: Set to 5.

- Validation: Use the built-in cross-validation (

selbal.cv()) to assess the predictive ability (AUC or RMSE) of the identified balance. - Output Interpretation: The algorithm returns the identified balance (two sets of taxa), its coefficients, and its cross-validated performance.

Protocol 2: Conducting Differential Abundance Analysis with ANCOM-BC

- Data Object: Load your data into a

phyloseqobject or create aSummarizedExperimentobject. - Model Specification: Use the

ancombc()function. Crucial argument isformula, where you specify your fixed effects (e.g.,~ disease_state + batch). - Zero Handling: Set

zero_cut = 0.90to ignore taxa with >90% zeros. The method uses a pseudo-count prior internally. - Results Extraction: Extract the

resobject, which contains data frames forbeta(log-fold changes),se(standard errors),W(test statistics), andp_val(p-values) for each taxon and covariate. - Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a false discovery rate (FDR) correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to the p-values for the covariate of interest.

Data Summaries

Table 1: Comparison of Compositionally-Aware Feature Selection Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Handles Zeros? | Output | Robust to Multicollinearity? | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELBAL | Identifies a single, optimal log-ratio balance | Requires low sparsity | A predictive balance (two taxa groups) | High (constructs a ratio) | Supervised biomarker discovery |

| ANCOM-BC | Linear model with bias correction & sampling fraction | Pseudo-count prior | DA taxa with log-fold changes | Medium (regularized estimation) | Identifying individual DA features |

| ALDEx2 | Monte-Carlo Dirichlet sampling, CLR, MW test | Dirichlet prior | Posterior effect sizes & p-values | Low | General DA testing, small n |

| CLR-LASSO | CLR transform + L1-penalized regression | Requires pseudo-count | Sparse set of predictive taxa | High (via regularization) | High-dimensional prediction |

| SparCC | Iterative correlation estimation on log ratios | Excludes zeros | Inferred correlation network | N/A (network inference) | Unsupervised ecological inference |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: SELBAL Algorithm Workflow

Diagram 2: ANCOM-BC Model Structure

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Compositional Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

R/Bioconductor phyloseq |

Data container and preprocessing engine for microbiome data. | Essential for organizing OTU tables, taxonomy, and sample metadata. |

zCompositions R package |

Implements Bayesian-multiplicative replacement of zeros. | Preferred method for handling zeros prior to CLR transformation. |

selbal R package |

Implements the SELBAL algorithm for balance discovery. | Use selbal.cv() for mandatory cross-validation. |

ANCOMBC R package |

Implements the ANCOM-BC differential abundance testing framework. | Key function: ancombc() with formula specification. |

ALDEx2 R package |

Compositional DA tool using Dirichlet-multinomial simulation. | Provides robust effect size estimates (effect column). |

mia R package (Bioconductor) |

Implements microbiome-specific compositional data analysis tools. | Includes tools for balance analysis (e.g., trainBalance). |

| Proper Metadata Table | Comprehensive sample covariate information. | Critical for including confounders in models (ANCOM-BC, etc.). |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ Section

Q1: During feature selection in QIIME2, my script fails with a "matrix is singular" error. How is this related to multicollinearity and how do I fix it?

A: This error often indicates perfect multicollinearity, where one ASV/OTU is a linear combination of others, common in microbiome data due to co-occurring taxa. To address this within a QIIME2 workflow:

- Pre-filtering: Use

qiime feature-table filter-featureswith--p-min-frequencyand--p-min-samplesto remove rare features that cause instability. - Aggregation: Collapse taxa to a higher taxonomic level (e.g., Genus) using

qiime taxa collapseto reduce redundancy. - Variance Threshold: Apply

qiime feature-table filter-features --p-min-frequencyto remove low-variance features. - Post-modeling Selection: Run your primary analysis (e.g., DESeq2 via

qiime deic2), then export the feature table and apply a multicollinearity-handling method (like LASSO regression) in R/Python on the significant features.

Q2: In mothur, my classify.otu output has many taxa with identical distributions across samples, leading to model convergence issues in downstream R analysis. What step did I miss?

A: This points to highly correlated features. Integrate correlation-based filtering into your mothur pipeline:

- After generating your shared file (e.g.,

final.an.shared), generate a correlation matrix in R using thecor()function on the transposed feature table. - Identify feature pairs with correlation > |0.95|.

- Create a "redundant list" file and use

mothur > remove.groups()to remove one feature from each highly correlated pair before downstream analysis. This preprocessing reduces multicollinearity before feature selection.

Q3: When using qiime composition add-pseudocount before ANCOM-BC, my results show an inflated number of significant features. Is this a multicollinearity artifact?

A: Potentially, yes. While ANCOM-BC is robust to compositionality, it does not explicitly handle multicollinearity. Highly correlated features can all appear significant. Solution: Integrate a variance-stabilizing step and post-hoc correlation check.

1. Run ANCOM-BC as standard (qiime composition ancombc).

2. Export the significant features and their CLR-transformed abundances.

3. In R, calculate the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for these significant features. Remove features with VIF > 10 iteratively.

4. Re-run the final statistical model on the decorrelated set.

Q4: For shotgun metagenomic functional pathway analysis (using HUMAnN3), how do I handle multicollinearity in pathway abundance data before machine learning?

A: Functional pathway abundances are often highly correlated. Integrate the following protocol:

| Step | Tool/Code | Purpose | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Normalization | humann3 renorm |

Renormalize pathway abundances to Copies per Million (CPM) | --units cpm |

| 2. Filter Low Abundance | Custom R/Python script | Remove low-variance pathways | Keep features with variance > 25th percentile |

| 3. Address Collinearity | stats R package |

Calculate pairwise Spearman correlation | cor(method="spearman") |

| 4. Feature Reduction | caret::findCorrelation |

Identify & remove one feature from correlated pairs | cutoff = 0.9 |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Errors & Solutions

| Error Message | Likely Cause | Integrated Solution (within QIIME2/mothur workflow) |

|---|---|---|

"Model did not converge" in qiime longitudinal linear-mixed-effects |

High multicollinearity among input features. | Pre-process with SparCC (qiime diversity sparcc) to identify correlations, then filter the feature table. |

"NA/NaN/Inf" errors in R after qiime tools export |

Perfect multicollinearity causing matrix inversion failure. | Integrate qiime deicode rpca for robust, regularized dimensionality reduction before export. |

| Unstable, highly variable feature importance scores in random forest. | Correlated predictors skewing importance measures. | Use qiime sample-classifier regress-samples with the --p-parameter-tuning flag to enable internal feature selection, or use --p-estimator to specify L1-penalized (lasso) models. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrating Correlation Filtering into a QIIME2 Feature Selection Pipeline

Objective: To produce a decorrelated feature table for robust downstream statistical modeling.

- Input: A QIIME2 feature table (

.qza), filtered to remove singletons and rare features. - Export:

qiime tools export --input-table feature-table.qza --output-path exported - Convert to TSV: Use

biom convert -i feature-table.biom -o table.tsv --to-tsv R Script for Correlation Filtering:

Re-import to QIIME2: Convert the TSV back to a BIOM file and import with

qiime tools import.

Protocol 2: Incorporating Regularized Regression (LASSO) Post-mothur Classification

Objective: Apply a feature selection method inherently handling multicollinearity after standard mothur OTU analysis.

- Input: A mothur

consensus.taxonomyfile and the corresponding count table. - Merge & Format in R: Combine data and format for

glmnet. LASSO Regression Execution:

Output: A list of OTUs selected by LASSO, which are robust to multicollinearity, for further biological interpretation.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for handling multicollinearity.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting decision tree for multicollinearity errors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context of Multicollinearity & Feature Selection |

|---|---|

| QIIME2 Core (2024.2+) | Provides the ecosystem for data import, processing, and initial filtering steps crucial for reducing feature redundancy early. |

| mothur (v.1.48.0+) | Enables precise OTU clustering and taxonomic classification; the remove.groups command is key for pre-filtering correlated features. |

R caret & glmnet Packages |

Essential external tools for post-QIIME2/mothur analysis. caret::findCorrelation identifies redundant features; glmnet performs LASSO regression for embedded selection. |