Unveiling Microbial Dark Matter: How Single-Cell Sequencing is Revolutionizing Ecology and Drug Discovery

Single-cell sequencing technologies are fundamentally transforming microbial ecology by enabling researchers to explore the vast genetic and functional heterogeneity within bacterial populations.

Unveiling Microbial Dark Matter: How Single-Cell Sequencing is Revolutionizing Ecology and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Single-cell sequencing technologies are fundamentally transforming microbial ecology by enabling researchers to explore the vast genetic and functional heterogeneity within bacterial populations. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of microbial single-cell sequencing, the latest methodological advances like M3-seq and Microbe-seq, and critical troubleshooting strategies for common technical challenges. It further offers a comparative analysis of platform performance and validation techniques, illustrating how these tools yield novel insights into antibiotic persistence, phage-host interactions, and microbiome dynamics, thereby opening new avenues for therapeutic discovery and clinical application.

From Bulk to Single Cell: Unveiling the Hidden Diversity of Microbial Communities

The field of microbial ecology has undergone a profound transformation, driven by technological revolutions that have progressively enhanced our resolution of the microbial world. The historical trajectory has moved from traditional culturing, which revealed a limited fraction of microbial diversity, to bulk metagenomics, which provided a comprehensive but averaged view of community function, and finally to single-cell resolution, which now unlocks the genetic black box of individual microorganisms within their native contexts [1]. This evolution is critical because microbial populations, even those with identical genetic backgrounds, exhibit significant phenotypic and functional heterogeneity [2] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this intra-population variability is crucial for advancing studies in antimicrobial resistance, host-pathogen interactions, and industrial microbiology, as mean trait values often mask the unique contributions of individual cells [2].

The Limitations of Pre-Single-Cell Eras

The Culturing Bottleneck

Traditional microbial ecology relied on culturing techniques, which are inherently biased. It is estimated that over 99% of microorganisms resist cultivation under standard laboratory conditions, severely limiting the scope of discoverable diversity and function.

The Metagenomic Revolution and Its Shortcomings

The advent of high-throughput sequencing prompted the blossom of metagenomics, allowing researchers to sequence the collective genome of all microbes in an environment without the need for cultivation [3]. This approach answered two fundamental questions: "who is there and what are they doing" by annotating sequencing reads against functional databases [3].

However, metagenomics has significant bottlenecks:

- Difficulties in assembly and annotation: The process of assembling short reads from complex mixtures of genomes remains computationally challenging and often fails to produce complete genomes, particularly for low-abundance taxa [3] [4].

- The averaging effect: Bulk DNA extraction from environmental samples obscures the significant variability between individual bacterial cells, leading to an incomplete understanding of strain heterogeneity, phage-host interactions, and the precise linkage of metabolic functions to specific species [3] [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Microbial Sequencing Approaches

| Feature | Target (16S) Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics | Single-Cell Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | "Who is there?" | "Who is there and what are they doing?" | "What is each individual cell doing?" |

| Resolution | Taxonomic (genus level) | Community & functional (averaged) | Single-cell & functional |

| Ability to Link Function to Species | No | Partial, through binning | Yes, direct link |

| Genome Assembly Quality | Not applicable | Fragmented, especially for rare species | High-quality genomes possible |

| Key Limitation | Limited taxonomic & functional resolution | Assembly bottlenecks, averaging effect | Amplification bias, contamination |

The Advent of Single-Cell Resolution

Single-cell sequencing emerged as a powerful complementary technique to overcome the limitations of metagenomics [4]. By isolating and sequencing genetic material from individual bacterial cells, this technology allows for:

- Linking function to species: Directly associating metabolic capabilities with specific microbial taxa [3].

- Revealing heterogeneity: Uncovering intra-population variation in genetics and activity that is critical for adaptation [2] [1].

- Accessing rare biosphere: Generating high-quality genomes for species with low abundance that would be lost in metagenomic sequencing [3].

- Studying host-virus interactions and subspecies variations [3].

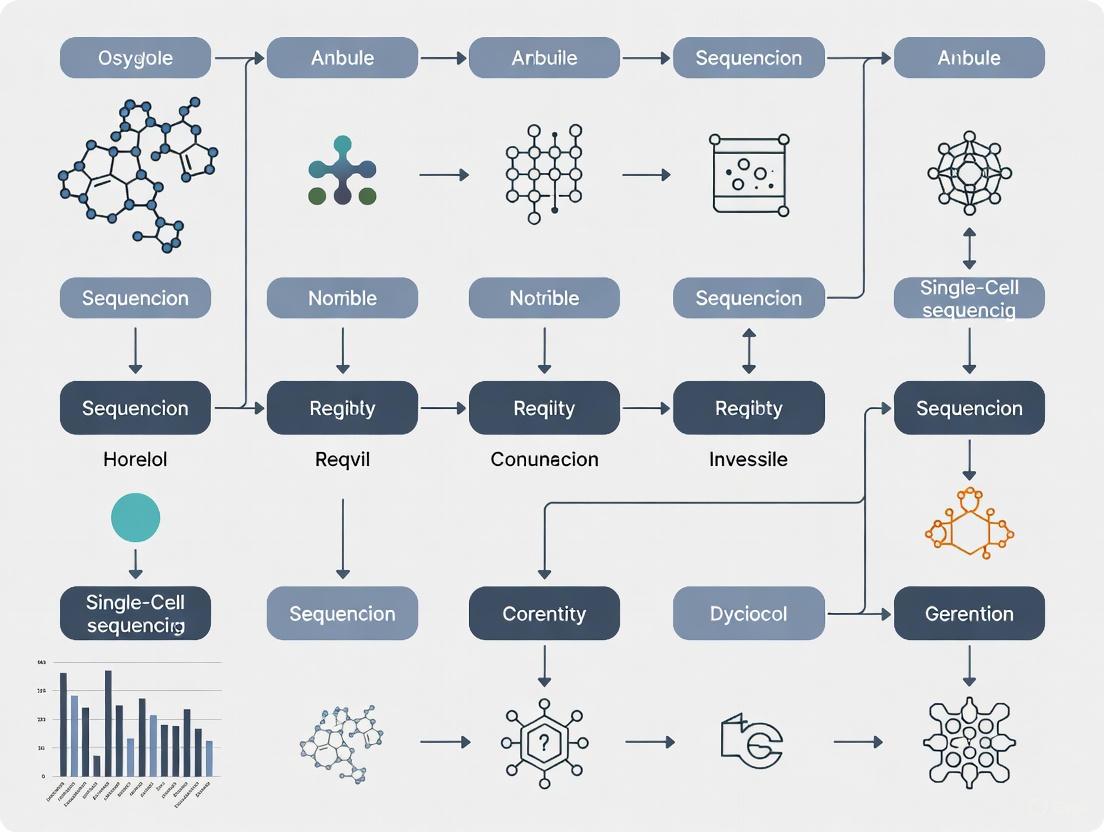

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logical relationships in single-cell metagenomics:

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Metagenomic Workflow

Key Technological Advances in Single-Cell Methods

Single-Cell Isolation and Whole Genome Amplification

The first step involves isolating single cells from environmental samples using microfluidics, flow cytometry, or micromanipulation [3]. A major breakthrough was the development of semi-permeable capsules (SPCs), which overcome limitations of traditional droplet microfluidics by allowing full reagent exchange and multi-step workflows on thousands of individual cells in parallel [4].

A critical innovation was Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA), which uses random hexamer primers and Phi29 DNA polymerase to amplify the femtograms of DNA in a single bacterial cell to micrograms required for sequencing [3]. Recent improvements like WGA-X use a thermo-stable mutant phi29 polymerase to recover a greater proportion of single-cell genomes [3].

Analytical Technologies: From Genomics to Metabolic Activity

Single-cell stable isotope probing (SC-SIP) techniques, particularly using Raman microspectroscopy and nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS), enable spatially resolved tracking of isotope tracers in individual cells [5]. This allows researchers to:

- Identify metabolically active cells within complex communities

- Measure cellular growth rates and metabolic heterogeneity

- Study cell-cell interactions including symbiosis, cross-feeding, and syntrophy [5]

Table 2: Quantitative Results from SPC-Based Single-Cell Sequencing [4]

| Sample Type | Sequencing Approach | Number of SAGs Detected | SAGs Used for Analysis | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sewage | Deep Sequencing | 1,796 | 576 | Linking ARGs to host species |

| Sewage | Shallow Sequencing | 12,731 | 2,456 | Broad microbial diversity mapping |

| Pig Feces | Deep Sequencing | 1,220 | 599 | Linking ARGs to host species |

| Pig Feces | Shallow Sequencing | 17,909 | 1,599 | Broad microbial diversity mapping |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SPC-Based Single-Cell Metagenomics

Sample Preparation and Cell Encapsulation

- Sample Collection & Storage: Collect environmental samples (e.g., sewage, feces) and store at -80°C prior to processing.

- Cell Detachment: Suspend 0.1 g of sample in 150 μL of 2.5% NaCl solution. Add 50 μL of detergent mix (100 mM EDTA, 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1% Tween 80) and 50 μL methanol. Shake vigorously for 60 minutes at 500 rpm.

- Sonication & Filtration: Sonicate three times for 1 minute each in a water bath. Add 1 mL of 2.5% NaCl and filter through an 8μM filter syringe.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge supernatant at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes. Remove supernatant and suspend cell pellets in 1x PBS. Wash twice at 8,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- SPC Generation: Use impedance flow cytometry to count cells. Generate SPCs on the ONYX platform using core and shell solutions, targeting 0.1 cells/SPC (lambda value) to minimize multiple encapsulations. Cross-link shells using light exposure device and recover SPCs with emulsion breaker solution.

Cell Lysis and DNA Amplification

- Enzymatic Lysis: Incubate SPCs in 1 mL mixed lysis solution (50 U/μL Lysozyme, 2 U/mL Zymolyase, 22 U/mL lysostaphin, 250 U/mL mutanolysin in PBS) at 37°C overnight. Wash SPCs three times with 1x PBS.

- Proteinase K Treatment: Incubate SPCs in 1 mL of 1 mg/mL Proteinase K in PBS at 40°C overnight. Wash three times with PBS.

- Alkaline Lysis: Resuspend SPCs in alkaline lysis solution (0.4 M KOH, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM DTT) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Wash three times with neutralization buffer (1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5) and three times with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with 0.1% Triton X-100.

- Whole Genome Amplification: Incubate SPCs with WGA mix at 45°C for 1 hour. Inactivate reaction at 65°C for 10 minutes. Wash SPCs three times with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with 0.1% Triton X-100.

- Quality Control: Stain SPCs with 1× SYBR Green in 1x PBS to confirm DNA amplification by fluorescence microscopy.

Barcoding and Sequencing

- DNA Debranching & End Preparation: Perform according to kit manual.

- Combinatorial Barcoding: Conduct four-step combinatorial split-and-pool barcoding to label DNA fragments with unique cell identifiers.

- Sequencing Approaches: Choose between:

- Deep Sequencing: Fewer cells (<2,000) with higher coverage for comprehensive genomic analysis.

- Shallow Sequencing: More cells (>10,000) with lower coverage for diversity assessment and abundance estimates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Metagenomics

| Item | Function | Example Products/Catalog Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| SPC Innovator Kit | Microfluidic encapsulation of single cells in semi-permeable capsules | Atrandi Biosciences CKN-G11 [4] |

| ONYX Platform | Instrument for high-throughput SPC production | Atrandi Biosciences CHN-ONYX2 [4] |

| Single-Microbe DNA Barcoding Kit | Whole genome amplification and combinatorial barcoding | Atrandi Biosciences CKP-BARK1 [4] |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) | Various suppliers [3] |

| Lysozyme, Zymolyase, Lysostaphin, Mutanolysin | Enzyme cocktail for bacterial cell wall lysis | Various suppliers [4] |

| Proteinase K | Protein degradation for DNA release | Promega [4] |

| Impedance Flow Cytometer | Accurate counting of bacterial cells for encapsulation | Bactobox (SBT instrument) [4] |

| Tripelennamine Hydrochloride | Tripelennamine Hydrochloride, CAS:154-69-8, MF:C16H21N3.ClH, MW:291.82 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bz-DTPA | Bz-DTPA, CAS:102650-30-6, MF:C22H28N4O10S, MW:540.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Addressing Technical Challenges in Single-Cell Genomics

The single-cell approach faces several technical hurdles that require specific solutions:

Contamination Control

DNA contamination is a major challenge as MDA can amplify contaminating DNA, leading to failed experiments. Solutions include:

- Experimental measures: Strict cleaning with ethylene oxide treatment of disposables, heat-sensitive DNA nucleases, UV irradiation of reagents, and HEPA-filtered environments [3].

- Computational approaches: Post-sequencing identification and removal of contaminated DNA by alignment to reference genomes or tetramer frequency-based composition analysis [3].

Overcoming Amplification Bias

MDA causes highly uneven read coverage and chimeric sequences. Mitigation strategies include:

- Experimental optimization: Reducing reaction volumes to increase effective template concentration, combining DNA samples of the same species, or using duplex-specific nuclease to degrade highly abundant sequences [3].

- Bioinformatic normalization: Screening and trimming reads according to k-mer depth before assembly using specialized software like SPAdes, EULER+Velvet-SC, or IDBA-UD [3].

The following diagram illustrates the main challenges and solutions in the single-cell genomics workflow:

Diagram 2: Single-Cell Technical Challenges & Solutions

Future Perspectives

The trajectory of microbial ecology continues to advance with several emerging technologies:

- Single-cell transcriptomics: Platforms like VITA now enable sequencing of single bacterial transcriptomes, revealing heterogeneity in gene regulation and responses to external stimuli [1].

- Mass spectrometry imaging: MALDI-MSI and SIMS techniques are being adapted to study metabolic interactions in complex microbial consortia at single-cell resolution [2].

- Integration with meta-omics: Single-cell genomics increasingly complements metagenomic data, providing reference genomes that improve metagenomic binning, while metagenomic reads can enhance single-cell genome assembly [3].

As these technologies mature, they will further unravel the complex interactions within microbial ecosystems, providing unprecedented insights for environmental science, medicine, and biotechnology.

Traditional bulk sequencing methods, such as metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, have profoundly advanced our understanding of microbial communities. However, these approaches provide population-averaged data, masking the substantial heterogeneity that exists among individual cells within genetically identical populations [6] [7]. Microbial single-cell genomics and transcriptomics have emerged to address this limitation, enabling the resolution of biological processes at the fundamental unit of life: the single cell. These techniques are redefining our understanding of microbiome function and dynamics, from uncovering transcriptional heterogeneity and antibiotic responses to characterizing mobile genetic elements in both simple biofilms and complex multispecies ecosystems [8].

In microbial ecology, the application of these methods is particularly valuable for dissecting the functional diversity of uncultivated species, unraveling host-microbe interactions at the cellular level, and identifying rare but critical subpopulations—such as antibiotic-persistent cells—that drive community responses to environmental stresses [6] [7]. This article provides a detailed overview of the core concepts, methodologies, and applications of microbial single-cell genomics (Microbe-seq) and transcriptomics (scRNA-seq), framed within the context of advancing ecological research.

Microbial Single-Cell Genomics (Microbe-seq)

Conceptual Foundation

Microbial single-cell genomics involves the sequencing of genomic DNA from individual microbial cells. Its primary goal is to obtain Single-Amplified Genomes (SAGs) from uncultivated or environmental microbes, bypassing the need for cultivation and enabling the exploration of microbial "dark matter" [9] [10]. This approach stands in contrast to Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs), which are consensus genomes reconstructed from mixed populations and may not accurately represent the genomes of distinct species or strains [6]. A key advantage of Microbe-seq is the ability to natively link mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids and phages, to their host cell chromosomes, providing insights into horizontal gene transfer and its role in microbial adaptation and evolution [9] [11].

Key Workflow and Protocol: High-Throughput SAG Generation

The following protocol outlines the major steps for obtaining high-quality SAGs from complex microbial communities, utilizing semi-permeable capsules for isolation and amplification [9].

- Step 1: Cell Encapsulation and Lysis. Individual microbial cells are isolated into semi-permeable capsules. The cells are then lysed using harsh chemical and enzymatic conditions to break down the rigid bacterial cell wall and access the genomic DNA [9] [11].

- Step 2: Whole Genome Amplification (WGA). The femtogram-level of DNA from a single cell is amplified to microgram quantities for sequencing. Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) is a widely used technique, employing random primers and the high-fidelity phi29 DNA polymerase in an isothermal reaction. This results in long amplification products, often exceeding 12 kb [10]. Recent advancements like WGA-X use a thermostable mutant of phi29 to improve genome recovery, particularly from cells with high GC content [10].

- Step 3: Single-Cell Barcoding and Library Preparation. The amplified genomes (SAGs) are tagged with unique molecular barcodes through iterative rounds of ligation. This allows for the pooling and multiplexed sequencing of thousands of SAGs while retaining the ability to trace each sequence back to its cell of origin [9]. Libraries can be prepared for either short-read or long-read sequencing platforms.

- Step 4: Sequencing and Data Analysis. The barcoded libraries are sequenced, and data is processed to yield demultiplexed SAGs for downstream assembly and analysis. SAGs can achieve >90% genome recovery per cell and often produce longer contigs than MAGs from corresponding samples [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Microbe-seq

Table 1: Key research reagents for microbial single-cell genomics.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Permeable Capsules | Physically isolates individual cells for processing | Enables high-throughput analysis of thousands of cells [9] |

| Lysis Buffers | Breaks open the tough microbial cell wall | Often contain lysozyme; optimized for Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria [6] |

| phi29 DNA Polymerase | Enzymatic driver of Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) | Used in Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) for high-fidelity, long-range amplification [10] |

| Barcoding Oligonucleotides | Uniquely labels DNA from each single cell | Allows for multiplexed sequencing and bioinformatic demultiplexing [9] |

| Microfluidic Device / FACS | High-throughput platform for single-cell isolation | Fluidigm C1, 10X Genomics; or Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting [7] |

| (Rac)-5-Hydroxymethyl Tolterodine | (Rac)-5-Hydroxymethyl Tolterodine, CAS:200801-70-3, MF:C22H31NO2, MW:341.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HU 331 | HU 331, CAS:137252-25-6, MF:C21H28O3, MW:328.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 1: Microbial single-cell genomics (Microbe-seq) workflow.

Microbial Single-Cell Transcriptomics (scRNA-seq)

Conceptual Foundation

Microbial single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) captures genome-wide transcriptional profiles of individual microbial cells. It is designed to uncover phenotypic heterogeneity within isogenic populations, identify rare cell types and metabolic states, and characterize specific host-bacterial interactions at the single-cell level [6] [7]. Applying scRNA-seq to bacteria presents unique technical hurdles that differentiate it from eukaryotic protocols. These challenges include: the absence of poly(A) tails on bacterial mRNAs, the very low total RNA content (approximately 0.1 pg, 100-1000 times less than a mammalian cell), the dominance of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) which constitutes >80% of total RNA, and the rigid cell wall that complicates lysis [6] [8] [12].

Key Workflow and Protocol: smRandom-Seq

smRandom-seq is a droplet-based high-throughput method that has been successfully applied to complex microbiomes, including human gut samples [8] [12]. The protocol below details its key steps.

- Step 1: Cell Fixation and Permeabilization. Bacteria are fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA) to crosslink and stabilize RNAs, proteins, and DNA. Cells are then permeabilized to allow entry of reagents for in-situ reactions [12].

- Step 2: In-Situ cDNA Synthesis with Random Primers. Unlike eukaryotic scRNA-seq that uses poly(T) primers, smRandom-seq uses random hexamer primers to capture all RNA types, circumventing the lack of poly(A) tails on bacterial mRNA. Reverse transcription occurs inside the permeabilized cell to generate cDNA [12]. A poly(dA) tail is later added to the 3' end of the cDNA using terminal transferase (TdT).

- Step 3: Droplet-Based Barcoding. Single bacteria are co-encapsulated with uniquely DNA-barcoded beads in microfluidic droplets. Within the droplet, the poly(A)-tailed cDNAs are released and captured by poly(T) primers on the beads, thereby labeling all cDNA from a single cell with the same unique barcode [12].

- Step 4: rRNA Depletion and Library Sequencing. After breaking the droplets and amplifying the pooled cDNA library, CRISPR-based depletion is used to selectively remove cDNA derived from ribosomal RNA. This crucial step enriches for mRNA sequences, reducing the rRNA percentage from over 80% to around 32% and significantly improving the efficiency of mRNA detection [12]. The library is then sequenced, and bioinformatic pipelines are used to attribute sequences to individual cells based on their barcodes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Microbial scRNA-seq

Table 2: Key research reagents for microbial single-cell transcriptomics.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Fixes cells to stabilize RNA and halt degradation | Standard crosslinking agent for preserving cellular contents [12] |

| Random Hexamer Primers | Initiates reverse transcription of all RNA types | Critical for capturing non-polyadenylated bacterial mRNA [7] [12] |

| Terminal Transferase (TdT) | Adds poly(A) tail to synthesized cDNA | Enables subsequent capture by poly(T) barcoding beads [12] |

| Barcoded Beads & Microfluidics | Tags all cDNA from a single cell with a unique barcode | Enables multiplexing of thousands of cells (e.g., 10X Chromium, custom systems) [7] [12] |

| CRISPR Cas9 Nuclease | Depletes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences from library | Dramatically increases the proportion of informative mRNA reads; alternative: RNase H [7] [12] |

| 2-Amino-4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine | 2-Amino-4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine|CAS 106447-97-6 | High-purity 2-Amino-4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine (CAS 106447-97-6) for life science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

| IPTG | IPTG, CAS:105431-82-1, MF:C9H18O5S, MW:238.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Microbial single-cell transcriptomics (scRNA-seq) workflow, based on smRandom-seq.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

The selection of an appropriate single-cell method depends heavily on the research question. The table below provides a direct comparison of bulk and single-cell approaches, as well as the distinct applications of genomics and transcriptomics.

Table 3: Comparison of microbial community analysis techniques, including single-cell methods.

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics | Microbial Single-Cell Genomics (Microbe-seq) | Microbial Single-Cell Transcriptomics (scRNA-seq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level [9] | Species-level [9] | Strain-level [9] | Strain-level & sub-strain states [8] |

| Functional Profiling | No [9] | Yes (Genetic potential) [9] | Yes (Genetic potential) [9] | Yes (Active expression) [7] |

| Linkage of Genes | No | No (MAGs) [6] | Yes (SAGs, plasmids, hosts) [9] | No (profiles mRNA only) |

| Handles Heterogeneity | No (Bulk average) | No (Bulk average) | Yes (Genomic variation) | Yes (Transcriptional variation) [6] |

| Key Application | Community composition | Gene catalog & MAG recovery | Genome assembly of uncultivated taxa [10] | Cell states, host-pathogen interactions, resistance mechanisms [6] [8] |

Application Notes in Microbial Ecology and Drug Development

Dissecting Antibiotic Responses and Persistence

Single-cell transcriptomics has proven invaluable for identifying and characterizing rare, transient subpopulations that survive antibiotic treatment. In a study profiling E. coli under ampicillin stress, smRandom-seq captured transcriptome changes in thousands of individual bacteria. It revealed distinct subpopulations with unique gene expression patterns, including the upregulation of SOS response and specific metabolic pathways, which were undetectable with bulk methods [12]. This granular view of heterogeneous stress responses provides new targets for overcoming antibiotic tolerance and persistence.

Elucidating Host-Microbe Interactions

Dual RNA-seq approaches now allow for the simultaneous profiling of host and bacterial transcriptomes at single-cell resolution. This has been used to uncover the mechanisms of infection, commensalism, and immune modulation. For example, the VITA platform (based on smRandom-seq) has been applied to model systems to demonstrate how hosts and commensal bacteria synergistically antagonize opportunistic pathogens, revealing phenotypic heterogeneity in bacterial pathogenicity at single-cell resolution [8].

Exploring Functional Heterogeneity and Redundancy in Complex Ecosystems

Single-cell techniques can map functional roles across species and within populations in natural environments. A landmark study of the bovine rumen microbiome using scRNA-seq analyzed over 2,500 microbial species and revealed extensive functional redundancy—where different species perform overlapping metabolic steps—as well as significant heterogeneity in gene expression within single species [8]. This resolves a key limitation of bulk metatranscriptomics, which cannot distinguish whether multiple functions are performed by many cells of one species or by a few cells from several species.

Linking Genomic Content to Host and Function

Single-cell genomics excels at connecting mobile genetic elements (MGEs) like plasmids and phage to their host chromosomes. This capability is crucial for tracking the flow of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence factors through microbial populations via horizontal gene transfer. By barcoding all DNA from a single cell, Microbe-seq can directly link an ARG on a plasmid to the genome of the bacterium that harbors it, providing a clear picture of the genetic drivers of adaptation and resistance in complex communities [9].

Within seemingly homogeneous bacterial populations lies a hidden world of cellular heterogeneity, a critical driver of adaptive behaviors such as antibiotic persistence, virulence, and metabolic specialization. For decades, this heterogeneity constituted a scientific 'black box' [13]. Conventional bulk genomic and transcriptomic techniques, which average signals across millions of cells, inevitably masked the crucial cell-to-cell variations that define population-level resilience and function [7] [6]. The advent of single-cell sequencing technologies has finally provided the key to unlocking this black box, enabling researchers to dissect microbial communities at an unprecedented resolution. This Application Note details the specific technical hurdles that historically obscured bacterial heterogeneity and presents the cutting-edge protocols and reagents that are now illuminating this dynamic field for microbial ecologists, disease researchers, and drug development professionals.

The Technical Barriers: Deconstructing the 'Black Box'

The transition from bulk to single-cell analysis in bacteriology presented a unique set of challenges that stalled progress for years. These challenges centered on the fundamental physiological and molecular differences between bacterial and mammalian cells.

The Physical and Molecular Barriers

The path to single-cell analysis is fraught with technical obstacles, each contributing to the historical opacity of bacterial heterogeneity.

- Rigid Cell Walls and Lysis: Bacterial cells are encased in a rigid exoskeleton—a thick layer of peptidoglycan in Gram-positive organisms and an additional outer membrane in Gram-negatives. Standard lysis buffers effective for mammalian cells are often inadequate, requiring optimized protocols involving lysozyme, EDTA, and Triton X-100 to permeabilize this barrier without degrading the precious, sparse RNA within [6].

- Minuscule RNA Quantity and Quality: A single bacterial cell contains approximately 0.1 pg of total RNA, which is 100-200 times less than a typical mammalian cell. Furthermore, only 4-5% of this RNA is mRNA, with the vast majority (>80%) being ribosomal RNA (rRNA). Bacterial mRNAs also lack poly(A) tails, have notoriously short half-lives (often only minutes), and exist at a mean copy number of just a few molecules per gene per cell [7] [6]. This combination of low abundance, instability, and lack of a universal capture handle rendered bacterial mRNA virtually invisible to standard single-cell RNA-seq protocols designed for eukaryotes.

The Historical Limitations of Bulk Sequencing

Traditional sequencing approaches, while foundational, were intrinsically limited for studying cellular variation as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Approaches in Microbial Ecology

| Feature | Bulk Metatranscriptomics | Single-Cell Genomics | Single-Cell Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-averaged | Individual cell | Individual cell |

| Functional Linkage | Indirect statistical association | Direct link of gene to phylogeny | Direct link of gene expression to cell state |

| Identifies Heterogeneity | No | Yes, for genetic elements | Yes, for transcriptional states |

| Sensitivity to Rare Cells | Low, signal diluted | Yes, given sufficient sequencing | High, can profile rare subpopulations |

| Key Challenge | Genome assembly, binning | Amplification bias, chimeras [3] | RNA capture, rRNA depletion [7] |

As outlined in Table 1, while metatranscriptomics could suggest "what" functions a community was performing, it could not determine "which" cells were responsible. Similarly, single-cell genomics could link genetic potential to a specific cell but could not reveal how that potential was dynamically expressed [3]. This critical gap in understanding functional heterogeneity was the core of the black box.

Modern Methodologies: Illuminating the Black Box

Recent technological breakthroughs have directly addressed the historical barriers, leading to the development of several powerful workflows for bacterial single-cell transcriptomics.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) Workflows

The core challenge of distinguishing mRNA from abundant rRNA has been tackled via two primary strategies: post-hoc rRNA depletion and targeted probe-based capture. A generalized workflow for these methods is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Generalized workflow for bacterial scRNA-seq. Following sample fixation, single cells are isolated and their transcripts are tagged with cellular barcodes (BCs) and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) using different indexing strategies. After library preparation, ribosomal RNA is depleted before final sequencing and data analysis [7] [14].

Key methodologies include:

- Combinatorial Indexing (e.g., PETRI-seq, microSPLiT): This approach uses iterative split-pooling steps to tag transcripts with unique barcode combinations, avoiding the need for physical cell isolation. While highly scalable, early versions suffered from a high percentage of rRNA-derived reads [7] [14].

- Droplet-Based Indexing (e.g., BacDrop, smRandom-seq): These methods use microfluidics to encapsulate single cells in droplets for barcoding. BacDrop performs rRNA depletion in situ using RNase H, whereas smRandom-seq uses random priming and has been successfully applied to human stool microbiomes [7].

- Massively-Parallel, Multiplexed, Microbial Sequencing (M3-seq): M3-seq combines combinatorial and droplet-based indexing, performing robust rRNA depletion after library amplification using RNase H. This post-hoc depletion strategy minimizes the risk of losing mRNA molecules before amplification, enhancing sensitivity. This protocol is detailed in Section 4.1 [14].

Microscopy-Based Spatial Techniques

As a complementary approach, imaging-based techniques like par-seqFISH and bacterial-MERFISH use multiple rounds of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with gene-specific probes to quantify and localize hundreds of transcripts within individual cells in their native spatial context, even within biofilms or host tissues [7].

Application Notes & Detailed Protocols

Protocol: M3-seq for Bacterial Single-Cell Transcriptomics

The M3-seq protocol is designed for high-throughput, transcriptome-scale profiling across many samples and conditions [14].

I. Sample Preparation and Round-One Indexing

- Cell Culture and Fixation: Grow bacterial cultures (e.g., E. coli MG1655, B. subtilis 168) to the desired phase (e.g., OD~600~ = 0.3 for exponential). Fix cells immediately using formaldehyde (e.g., 3% for 15 min) to preserve RNA and crosslink transcripts.

- Permeabilization: Pellet fixed cells and wash. Permeabilize the cell wall by resuspending in a buffer containing lysozyme (e.g., 1 mg/mL for 30 min at 37°C).

- In-Situ Reverse Transcription (Round-One Indexing): Distribute permeabilized cells across a 96-well plate. In each well, perform reverse transcription using a master mix containing:

- Random hexamer primers with a well-specific barcode (BC1) and a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI).

- Reverse transcriptase (e.g., Maxima H-).

- dNTPs and reaction buffer. This step tags all transcripts within a cell with the same BC1 and unique UMIs.

II. Pooling and Droplet-Based Round-Two Indexing

- Cell Pooling: Combine the contents of all 96 wells into a single tube. You now have a pool of cells where transcripts are pre-tagged with one of 96 BC1s.

- Droplet Generation and Lysis: Load ~100,000 pooled cells into a commercially available droplet system (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium Next GEM Single Cell ATAC kit). Within the droplets, cells are lysed, and a second, droplet-specific barcode (BC2) is ligated to the BC1-tagged cDNA molecules. The combination of BC1 and BC2 creates a unique combinatorial index for each cell.

III. rRNA Depletion and Library Construction

- Library Amplification and Transcription: Break the droplets and purify the barcoded cDNA. Amplify the library and transcribe it into single-stranded RNA.

- RNase H-based rRNA Depletion: Hybridize the RNA library to DNA oligonucleotides complementary to the dominant rRNA sequences of your target species. Add RNase H, which specifically cleaves RNA in RNA:DNA hybrids, thereby digesting the rRNA. This step has been shown to increase mRNA-aligned reads by 11-27 fold [14].

- Sequencing Library Prep: Reverse transcribe the rRNA-depleted RNA back into cDNA. Construct sequencing libraries using standard protocols (fragmentation, adapter ligation, PCR amplification). Sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq or similar platform.

Protocol: Functional Phenotyping with SDR-seq

For directly linking genomic variation to transcriptional phenotypes in microbial populations, Single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) is a powerful tool [15]. This protocol is adapted from mammalian cell studies and represents the frontier of multi-omic microbiology.

I. Cell Fixation and In-Situ Reverse Transcription

- Cell Fixation: Create a single-cell suspension from a microbial community. Fix cells using a non-crosslinking fixative like glyoxal, which preserves nucleic acid accessibility better than PFA.

- In-Situ RT and Preamplification: Permeabilize fixed cells. Perform in-situ reverse transcription using custom primers. For RNA, this can involve poly(dT) primers if studying a eukaryotic host, or random hexamers for the microbiome. For DNA, this step involves multiplexed targeted preamplification of specific genomic loci of interest (e.g., antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factors). Tag all products with a sample barcode and UMI.

II. Droplet-Based Multiplexed PCR

- Droplet Encapsulation and Lysis: Load the preamplified cells onto a platform like the Mission Bio Tapestri. Cells are encapsulated into first droplets, then lysed with proteinase K.

- Multiplexed PCR: A second droplet is formed containing the lysed cell, a barcoding bead with cell-specific barcodes, and primers for hundreds of targeted gDNA and RNA sequences. A multiplexed PCR simultaneously amplifies all targets, tagging them with the cell barcode.

III. Library Separation and Sequencing

- Library Separation: Break the droplets and pool the amplicons. Separate the gDNA and RNA libraries using distinct overhangs on their respective primers.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Generate NGS libraries for each modality. Sequence and bioinformatically process the data, using the cell barcodes to confidently pair gDNA genotypes (e.g., single-nucleotide variants in a resistance gene) with RNA expression phenotypes (e.g., upregulated stress response pathways) from the same cell [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the above protocols requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools, as cataloged in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Single-Cell Genomics

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme | Enzymatic digestion of peptidoglycan cell wall for permeabilization. | Concentration and incubation time must be optimized for different bacterial species [6]. |

| Random Hexamer Primers | Initiate reverse transcription of bacterial mRNA, which lacks a poly-A tail. | Essential for unbiased cDNA synthesis; can lead to high rRNA reads without depletion [7] [6]. |

| RNase H | Enzyme that cleaves RNA in RNA:DNA hybrids. | Used in post-hoc rRNA depletion (e.g., M3-seq); more sensitive than in-situ depletion [14]. |

| rRNA-specific DNA Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to hybridize to conserved rRNA sequences. | Used with RNase H for depletion; universal probe sets are needed for complex microbiomes [7]. |

| Combinatorial Barcodes | Unique nucleotide sequences to tag individual cells and transcripts. | Enable pooling of thousands of cells; reduce index collision rates (e.g., <1% in M3-seq) [14]. |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity polymerase used in Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) for single-cell genomics. | Can cause uneven coverage and chimeric reads; improved versions (WGA-X) are available [3]. |

| Microfluidic Chip (10X Genomics) | Generates nanoliter-scale droplets for single-cell barcoding. | Enables high-throughput processing; requires optimization of cell loading concentration [7] [14]. |

| Atrazine mercapturate | Atrazine mercapturate, CAS:138722-96-0, MF:C13H22N6O3S, MW:342.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-trans-leukotriene B4 | 6-trans-Leukotriene B4 | High Purity | For Research Use | 6-trans-Leukotriene B4, a leukotriene isomer for inflammation & immunology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Data Analytics and Visualization Tools

The complex, high-dimensional data generated by these technologies require advanced bioinformatic pipelines for interpretation.

- ViSCAR (Visualization and Single-Cell Analytics using R): This toolset allows for the exploration and correlation of single-cell attributes from live-cell imaging data. It can model spatiotemporal evolution, discover epigenetic inheritance, and characterize stochasticity in phenomena like persister cell formation [13].

- Standard scRNA-seq Pipelines: Tools like CellRanger and Seurat are adapted for bacterial data. The core steps include quality control, normalization, dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP), clustering, and cell type annotation. For dynamic processes, tools like Monocle and scVelo can infer pseudotemporal trajectories and RNA velocity [16].

- Ligand-Receptor Analysis: Tools like CellChat and CellPhoneDB can be used to infer intercellular communication networks within a microbial community, mapping how subpopulations may interact via secreted metabolites or signaling molecules [16].

The 'black box' of bacterial cellular heterogeneity has been pried open. The methodological breakthroughs in single-cell sequencing—addressing the profound challenges of cell lysis, RNA capture, rRNA depletion, and multi-omic integration—have provided an unparalleled view into the functional diversity of microbial life. These Application Notes provide a framework for employing these powerful protocols to link genetic identity to phenotypic function at the ultimate resolution. As these tools become more accessible and integrated into microbial ecology and clinical research, they promise to revolutionize our understanding of microbiome dynamics, pathogen behavior, and the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at controlling complex bacterial communities.

This application note details advanced protocols for investigating microbial survival strategies, focusing on the interplay between bet-hedging, persister cell formation, and phage infection dynamics. These phenomena are critical to understanding treatment failure in chronic infections and the evolution of antibiotic resistance. The content is framed within a broader research thesis utilizing single-cell sequencing to dissect microbial heterogeneity and function in complex ecological contexts. The guidance provided is intended for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to incorporate cutting-edge microbial ecology techniques into their work.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Dynamics

Bet-Hedging as an Evolutionary Strategy

Bet-hedging is an evolutionary strategy that maximizes long-term fitness by reducing variance in reproductive success across generations in an unpredictable environment. In immunological and microbial contexts, it involves a population proactively generating phenotypic diversity, ensuring that some subsets survive under unforeseen conditions [17]. This is categorized as either conservative bet-hedging (a single, generalist phenotype) or diversified bet-hedging (multiple, distinct phenotypes produced simultaneously) [17].

Table 1: Characteristics of Evolutionary Strategies in Fluctuating Environments

| Strategy | Description | Immunological Context | Key Benefit | Key Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversible Plasticity | Phenotype shifts toward an optimum in response to environmental signals. | Immune cell activation; inducible responses. | Responsive to predictable environmental change. | Can lag behind rapidly changing environments. |

| Irreversible Plasticity | Phenotype is determined by environmental conditions during development. | Helper T cell polarization and differentiation. | Beneficial if environment is predictable within a lifetime. | Costly during co-infections or with heterogeneous signals. |

| Conservative Bet-Hedging | A single phenotype that is suboptimal but not catastrophic in most environments. | A specialized response not specific to a signal. | Minimizes variance in fitness across time. | Suboptimal in any given environment. |

| Diversified Bet-Hedging | Proactive variation in offspring phenotypes is generated. | Generation of multiple immune cell phenotypes regardless of environment. | Optimal for rapidly changing, unpredictable environments. | Each phenotype is potentially costly in the wrong environment. |

In microbial systems, bet-hedging can manifest as a subpopulation entering a dormant or persister state, a form of diversified bet-hedging that protects the population from sudden eradication by phage predation or antibiotic treatment [18].

Phage-Bacteria Interaction Parameters

Quantitative modeling of phage-bacteria dynamics is essential for predicting the outcome of phage therapy. Key parameters include growth rates, infection rates, and the emergence of resistant or persistent populations.

Table 2: Experimentally Derived Parameters from Phage-Bacteria Dynamics Studies

| Organism & Phage | Parameter | Symbol | Estimated Value | Notes | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (no phage) | Intrinsic Growth Rate | k | 0.469 - 0.602 hâ»Â¹ | Depends on initial OD; Carrying Capacity (C): ~0.810-0.877 (OD) | [19] |

| K. pneumoniae with phage vBKpn2-P4 | Infection Rate | Ï | 0.9359 - 0.9625 | [19] | |

| Burst Size | β | 170.4 - 225.8 phage/cell | Previous estimates for other Kpn phages range from ~32 to 303. | [19] | |

| Rate of Emergence of Resistant Bacteria | μ | 0.4449 - 0.5544 | Probability from wild-type duplication. | [19] | |

| Phage-Induced Cell Death Rate | η | 0.7879 - 0.8542 hâ»Â¹ | Very high compared to bacterial growth rate. | [19] | |

| Campylobacter jejuni with phage | Proliferation Threshold | ~10â´ CFU/mL | Bacterial concentration required for phage population growth. | [20] |

These quantitative insights reveal the rapid emergence of phage-resistant mutants, which can outcompete susceptible strains and complicate phage therapy [19]. Furthermore, the existence of threshold phenomena, such as the proliferation threshold (bacterial density required for phage population growth), is a critical concept not found in traditional antibiotic pharmacokinetics [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolating and Differentiating Phage-Resistant vs. Persister Cells

This protocol allows for the separation and quantification of genetically resistant mutants from phenotypically tolerant persister cells following phage exposure [21].

Workflow: Isolation of Phage Survivors and Persister Assay

Materials:

- Lytic Phage Stock: e.g., T2, T4, or lambda (cI mutant) for E. coli; Kp11 for K. pneumoniae [21] [22].

- Bacterial Strain: e.g., E. coli BW25113 or a clinical isolate [21].

- Growth Medium: Lytic Broth (LB) [21].

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS): For washing and dilution [21].

- LB Agar Plates: With and without phage supplementation.

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Inoculate a single bacterial colony into 15 mL of LB broth and incubate with shaking (250 rpm) at 37°C until the culture reaches the late exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5) [21].

- Phage Challenge: Add lytic phage to the culture at a Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) of approximately 0.1. Incubate for 3-4 hours with shaking [21].

- Wash and Plate: After incubation, wash the culture twice with PBS to remove external phages. Perform serial dilutions in PBS.

- Plate 100 µL of appropriate dilutions onto standard LB agar plates to determine the total number of surviving cells.

- Plate 100 µL of the same dilutions onto LB agar plates containing a high titer of the same phage. Only genetically resistant mutants will grow on these plates [21].

- Incubation and Enumeration: Incubate all plates overnight at 37°C. Count the resulting Colony Forming Units (CFUs).

- Calculation: The population of persister cells is calculated as the difference between the total survivors (from phage-free plates) and the resistant mutants (from phage-containing plates) [21].

Protocol 2: Generating and Confirming a Phage-Tolerant Persister State

This protocol uses rifampin pretreatment to artificially enrich a culture for persister cells, which can then be challenged with phages to study tolerance mechanisms [21].

Materials:

- Rifampin Stock Solution: 100 mg/mL in DMSO.

- Ampicillin Stock Solution: Or another appropriate antibiotic at 10x MIC.

- Lytic Phage Stock.

Procedure:

- Persister Enrichment: Grow a bacterial culture to late exponential phase. Treat with rifampin (100 µg/mL) for 30 minutes to inhibit transcription in growing cells [21].

- Lysis of Non-Persisters: Add ampicillin (10x MIC) and incubate for a duration sufficient to lyse the majority of non-persister, growing cells (e.g., 4 hours) [21].

- Phage Challenge: Wash the enriched persister population twice with PBS to remove antibiotics. Resuspend in fresh medium and challenge with lytic phage at an MOI of ~0.1 for 3 hours [21].

- Viability Assessment: Wash cells twice with PBS to remove external phages. Perform serial dilutions and plate on LB agar to enumerate viable cells. Compare the survival rate of the rifampin-pre-treated population to an untreated control to confirm enhanced phage tolerance [21].

Protocol 3: Single-Cell Sequencing of Phage Survivors

This protocol leverages single-cell genomics to link phylogenetic identity to functional genes and viral elements in individual bacterial cells that survive phage challenge, directly addressing the thesis context of microbial ecology [3] [23].

Workflow: Single-Cell Sequencing of Phage Survivors

Materials:

- Cell Sorter: Microfluidics device or fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS).

- Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) Kit: Containing Phi29 DNA polymerase and random hexamer primers [3].

- DNA Clean-up Kit.

- Library Prep Kit for high-throughput sequencing.

- UV-treated reagents and HEPA-filtered environment to minimize contamination [3].

Procedure:

- Single-Cell Isolation: After a phage killing assay, isolate individual bacterial cells from the surviving population. This can be achieved through serial dilution, micromanipulation, flow cytometry, or microfluidics [3] [23].

- Whole Genome Amplification (WGA): Lyse individual cells and amplify their genomic DNA using Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA). This step is critical as a single bacterial cell contains only femtograms of DNA [3].

- Note: MDA can introduce chimeric reads and uneven genome coverage. The use of a thermo-stable mutant phi29 polymerase (e.g., in WGA-X) can improve genome recovery [3].

- Library Construction and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified DNA and sequence using an appropriate high-throughput platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Assembly and Binning: Assemble reads into contigs and bin them by individual cell.

- Contamination Control: Identify and remove contaminated sequences by aligning to reference genomes (e.g., human) or using tetramer frequency-based composition analysis [3].

- Coverage Normalization: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., SPAdes, IDBA-UD) to screen and trim reads based on k-mer depth to mitigate coverage unevenness [3].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate genomes to identify genes, including phage defense systems, virulence factors, and metabolic pathways, directly linking function to the single cell's phylogeny [23].

Visualization of Key Mechanisms and Workflows

Bacterial Survival Strategies Under Phage Pressure

The following diagram summarizes the decision tree of bacterial survival mechanisms when faced with lytic phage infection, integrating concepts of bet-hedging, resistance, and persistence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example(s) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lytic Phages | To exert selective pressure and study infection dynamics. | T2, T4, lambda (cI) for E. coli; Kp11 for K. pneumoniae; Paride for P. aeruginosa. | Select a well-characterized, strictly lytic phage. MOI is critical for experimental design. |

| Defined Growth Media | To ensure reproducible growth and entry into stationary phase/dormancy. | Lytic Broth (LB), M9 minimal medium. | Use a fully defined medium for rigorous studies of dormancy [18]. |

| Antibiotics for Selection | To isolate or enrich for specific populations (e.g., persisters). | Rifampin, Ampicillin. | Use at high concentrations (e.g., 10x MIC) to lyse non-persister cells [21]. |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase & MDA Kits | For Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) in single-cell genomics. | Commercial MDA kits, WGA-X. | Essential for amplifying femtograms of DNA from a single cell to micrograms for sequencing [3]. |

| Microfluidic Cell Sorter | To isolate individual bacterial cells from a mixed population. | Commercial flow cytometers, custom microfluidic devices. | Enables high-throughput single-cell isolation for sequencing [3] [23]. |

| Phage-Resistant Mutant Strains | As controls in persistence assays and for studying resistance mechanisms. | Spontaneous resistant mutants isolated from plaques. | Characterize colony morphology (e.g., mucoidy) and confirm stable resistance [21]. |

| Sorbitan Sesquioleate | Sorbitan Sesquioleate | Non-Ionic Surfactant | Sorbitan sesquioleate is a non-ionic surfactant for research, ideal for stabilizing emulsions. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Nafenopin-CoA | Nafenopin-coenzyme A | High-Purity PPARα Research | Nafenopin-coenzyme A is a high-purity conjugate for metabolic & PPARα pathway research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

A Technical Deep Dive: Platforms, Workflows, and Groundbreaking Applications

Single-cell sequencing technologies have transformed microbial ecology by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity in complex biological systems, moving beyond the limitations of population-level average measurements [24] [12]. While initially developed for eukaryotic cells, these techniques now empower researchers to investigate individual microbial genotypes and functional expression, revealing unprecedented diversity within isogenic populations [25] [12]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of three principal technological platforms—plate-based, droplet-based, and split-pool barcoding—for single-cell transcriptomics in microbial systems. Each method addresses the unique challenges of bacterial transcriptomics, including low RNA content, lack of polyadenylated tails, tough cell walls, and small cell size [24] [26] [12]. The selection of an appropriate platform is crucial for experimental success, balancing throughput, sensitivity, cost, and technical accessibility to address specific research questions in microbial ecology, host-pathogen interactions, and antibiotic resistance.

Platform Comparison Tables

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

| Feature | Plate-Based Methods | Droplet-Based Methods | Split-Pool Barcoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Physical isolation of cells into multi-well plates [27] | Microfluidic co-encapsulation of cells with barcoded beads in droplets [27] [12] | Combinatorial barcoding via successive rounds of pooling and splitting [26] [27] |

| Typical Throughput | Low to medium (96-384 wells) [27] | High (Thousands to tens of thousands of cells) [12] | Very High (Tens of thousands of cells) [26] |

| mRNA Capture Chemistry | Poly(T) and/or random hexamers | Primarily poly(T) after poly(A) tailing; random primers in smRandom-seq [12] | Random hexamers, often with in-situ polyadenylation [26] |

| Key Technical Challenges | Low throughput, labor-intensive, cell loss [25] | Bacterial lysis in droplets, RNA capture efficiency [12] | Cell clumping/doublets, ligation errors, complex bioinformatics [27] |

| mRNA Enrichment Strategy | Ribosomal RNA depletion probes [26] | CRISPR-based rRNA depletion (e.g., smRandom-seq) [12] | Enzymatic polyadenylation + Terminator exonuclease [26] |

| Automation & Equipment Needs | Liquid handler, cell sorter | Specialized microfluidic equipment [12] | Standard lab equipment (no custom machinery) [27] |

| Relative Cost per Cell | High | Medium | Low, especially at large scale [27] |

Table 2: Application Suitability and Data Output

| Characteristic | Plate-Based Methods | Droplet-Based Methods | Split-Pool Barcoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Use Cases | Small, targeted studies; validation; precious samples | Large-scale profiling of heterogeneous populations | Population-scale studies; labs without microfluidics [27] |

| Species Specificity | High (manual selection) | High (~99% in smRandom-seq) [12] | High (99.2% in microSPLiT) [26] |

| Typical Genes/Cell | Varies by protocol | ~1000 genes for E. coli (smRandom-seq) [12] | 138 for E. coli, 230 for B. subtilis (microSPLiT) [26] |

| Doublet/Multiplet Rate | Very low | Low (e.g., 1.6% in smRandom-seq) [12] | Moderate (increases with cell clumping) [27] |

| Data Complexity | Standard NGS analysis | Standard droplet-based pipelines | Complex demultiplexing required [27] |

| Commercial Examples | SMART-seq3 [27] | 10X Genomics, Parse Biosciences (evergreen) | Parse Biosciences (SPLiT-seq), Atrandi Biosciences [28] [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: Microbial Split-Pool Ligation Transcriptomics (microSPLiT)

Based on: Kuchina et al., Science (2020) [26]

Sample Preparation and Fixation:

- Grow bacterial cultures (e.g., B. subtilis PY79, E. coli MW1255) to the desired optical density (e.g., OD₆₀₀ = 0.5).

- Fix cells immediately by adding ice-cold 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) to a final concentration of 1.6% and incubate on ice for 1 hour.

- Quench the fixation reaction with 1.25M glycine.

- Pellet cells, wash with PBS, and resuspend in a permeabilization buffer.

Permeabilization and mRNA Enrichment:

- Permeabilize fixed cells using a combination of lysozyme (for gram-positive) and a mild detergent like Tween-20 (for gram-negative). Optimization is critical for different species [26].

- To enrich for mRNA, treat permeabilized cells with E. coli Poly(A) Polymerase I (PAP) to preferentially add poly(A) tails to bacterial mRNA. This was found to increase mRNA reads approximately 2.5-fold [26].

- Alternatively, test 5'-phosphate-dependent exonuclease (Terminator exonuclease) to degrade processed rRNA.

Split-Pool Barcoding (4 Rounds):

- Round 1: Distribute the cell suspension across a 96-well plate, where each well contains a unique Barcode 1 and reverse transcription primers (a mix of random hexamers and poly-T primers). Perform in-cell reverse transcription.

- Pool and Split: Pool all cells from the plate, then randomly redistribute them into a new 96-well plate.

- Round 2: In the new plate, ligate a well-specific Barcode 2 to the cDNA. Repeat the pool-and-split process for Rounds 3 and 4 to ligate Barcodes 3 and 4.

- Note: After RT, mild sonication is required to break cell clumps and ensure a single-cell suspension for subsequent rounds [26].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- After the final barcoding round, pool all cells and extract the barcoded cDNA.

- Prepare a sequencing library via PCR amplification.

- Sequence on an Illumina platform. Demultiplex cells bioinformatically using their unique combination of four barcodes.

Protocol 2: Droplet-based Single-Microbe RNA-seq (smRandom-seq)

Based on: Wang et al., Nature Communications (2023) [12]

Fixation and Permeabilization:

- Fix bacteria overnight in ice-cold 4% PFA to crosslink cellular components.

- Permeabilize fixed cells to allow reagent entry for in-situ reactions.

In-Situ cDNA Synthesis with Random Primers:

- Add random primers containing a GAT 3-letter PCR handle to the permeabilized cells.

- Perform multiple temperature cycles to maximize primer binding to transcripts.

- Conduct in-situ reverse transcription to generate first-strand cDNA.

- Use Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) to add a poly(dA) tail to the 3' end of the cDNA. This is a critical step that allows subsequent capture by poly(T) barcodes in droplets [12].

- Wash cells after each step to remove excess primers and reagents.

Droplet Encapsulation and Barcoding:

- Encapsulate single bacteria with a poly(T) barcoded bead in a ~100 μm droplet using a custom microfluidic device. The beads are synthesized with unique barcodes via a 3-step ligation reaction [12].

- Inside the droplet, release the poly(T) primers from the bead using USER enzyme cleavage and release the cDNA from the bacteria using RNase H.

- The poly(T) primers hybridize to the poly(dA)-tailed cDNAs, and a barcoding reaction is performed to tag all cDNAs from a single cell with the same cell barcode and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs).

Library Prep and rRNA Depletion:

- Break the droplets and amplify the barcoded cDNA library via PCR.

- Perform CRISPR-based ribosomal RNA depletion on the final library to significantly enrich for mRNA (reducing rRNA percentage from ~83% to 32%) [12].

- Sequence the library on a short-read platform.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflow of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Platforms

Diagram 2: Bioinformatics Pipeline for Split-Pool Data Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Poly(A) Polymerase I | Enzymatically adds poly(A) tails to bacterial mRNA for capture in microSPLiT and related protocols [26]. |

| Lysozyme & Tween-20 | Critical for optimizing permeabilization of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial cell walls, respectively [26]. | |

| Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) | Adds poly(dA) tails to cDNA in smRandom-seq, enabling subsequent capture by poly(T) barcodes [12]. | |

| USER Enzyme | Used in smRandom-seq to efficiently release barcoded primers from beads within droplets [12]. | |

| CRISPR-guided rRNA Depletion Kit | Dramatically enriches mRNA fraction in final sequencing libraries (e.g., from 83% to 32% rRNA) [12]. | |

| Computational Tools | CleanBar | A flexible, open-source tool for demultiplexing reads from split-and-pool barcoding, handling ligation errors and variable barcode positions [28]. |

| splitpipe & STARsolo | Recommended bioinformatics pipelines for processing SPLiT-seq data, balancing speed and accuracy [27]. | |

| SCSit, zUMI, alevin-fry splitp | Alternative pipelines for SPLiT-seq data processing, each with different strengths and computational demands [27]. | |

| Commercial Platforms | Atrandi Biosciences System | A commercial platform using semi-permeable capsules and split-pool barcoding for microbial single-cell genomics [28]. |

| Parse Biosciences | Provides commercialized, accessible SPLiT-seq kits for single-cell transcriptomics without specialized microfluidics [27]. | |

| Lixumistat hydrochloride | Lixumistat hydrochloride, MF:C13H17ClF3N5O, MW:351.75 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyltetrazine-Sulfo-NHS ester sodium | Methyltetrazine-Sulfo-NHS ester sodium, MF:C15H13N5NaO7S, MW:430.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The study of microbial communities has been revolutionized by sequencing technologies, yet traditional metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches measure bulk expression, averaging signals across entire populations and obscuring crucial single-cell heterogeneity [7]. Even genetically identical bacteria can exhibit functional specialization, leading to distinct subpopulations such as antibiotic-resistant persisters or metabolically variant cells that are essential for population survival but invisible to bulk measurements [29]. The development of high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) for bacteria addresses this critical gap, enabling the unbiased discovery of rare cell states and transcriptional dynamics within complex microbial communities [14] [7].

Two prominent platforms, M3-seq (Massively-parallel, Multiplexed, Microbial sequencing) and BacDrop, have emerged as powerful tools for large-scale bacterial single-cell transcriptomics. Both methods leverage combinatorial barcoding strategies to profile hundreds of thousands of bacterial cells in single experiments, providing unprecedented resolution to investigate microbial ecology, host-pathogen interactions, antibiotic resistance, and phage infection dynamics [14] [7]. This article details their methodologies, applications, and protocols to guide researchers in employing these transformative technologies.

M3-seq and BacDrop represent significant advancements over earlier bacterial scRNA-seq methods like MATQ-seq and PETRI-seq, which were limited in throughput to a few thousand cells [14]. They belong to a broader ecosystem of technologies that also includes microSPLiT (a combinatorial indexing method requiring no specialized equipment) and smRandom-seq (a droplet-based method requiring custom microfluidics) [7].

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Bacterial scRNA-seq Platforms

| Feature | M3-seq | BacDrop | microSPLiT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (cells) | 10ⵠ- 10ⶠ[14] | 10ⵠ- 10ⶠ[7] | 10ⵠ- 10ⶠ[29] |

| mRNA Capture | Random priming [14] | Random priming [7] | Random priming & poly(A) tailing [29] |

| rRNA Depletion | RNase H (post-library) [14] | RNase H (in-cell stage) [7] | Poly(A) polymerase enrichment [29] |

| Barcoding Strategy | Combinatorial (in-situ + droplet) [14] | Droplet-based [7] | Combinatorial (split-pool) [29] |

| Specialized Equipment | 10X Genomics Chromium [14] | 10X Genomics Chromium [7] | None [29] |

| Key Application Example | Phage infection, bet-hedging [14] | Heterogeneous MGE expression [7] | Metabolism, sporulation [29] |

M3-seq combines plate-based in situ indexing with droplet-based indexing to assign a unique combinatorial barcode to each cell's transcripts [14]. A critical innovation is its implementation of post-hoc rRNA depletion using RNase H after library amplification, which reportedly reduces the risk of losing non-rRNA transcripts and increases sensitivity for mRNA, tRNAs, sRNAs, and UTRs [14].

BacDrop is a droplet-based method that also uses random priming for mRNA capture but performs in-cell rRNA depletion with RNase H prior to library amplification [7]. Its compatibility with the widely available 10X Genomics Chromium controller enhances its accessibility [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of M3-seq from Pilot Studies

| Metric | Exponential Phase E. coli | Stationary Phase E. coli |

|---|---|---|

| Reads per Cell (pre-depletion) | ~1,000-2,000 [14] | Similar range [14] |

| rRNA Read Proportion (pre-depletion) | 90-97% [14] | High [14] |

| Fold Increase in mRNA Reads (post-depletion) | 11-27x [14] | 11-27x [14] |

| Fold Increase in tRNA Reads (post-depletion) | 15-20x [14] | 15-20x [14] |

| Index Collision Rate (with combinatorial barcoding) | 0.7% - 1.5% (corrected) [14] | 0.7% - 1.5% (corrected) [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

M3-seq Protocol

The M3-seq protocol involves two primary rounds of indexing and a crucial post-amplification rRNA depletion step [14].

Part 1: Sample Preparation and Indexing

- Cell Fixation and Permeabilization: Grow bacterial cultures to the desired phase (e.g., OD₆₀₀ = 0.3 for exponential). Harvest cells and fix immediately with formaldehyde to preserve the transcriptomic state. Wash fixed cells and permeabilize using lysozyme and mild detergents to enable access for enzymes and oligonucleotides while maintaining cell integrity [14].

- Round-One Indexing (In Situ): Distribute the permeabilized cells into a 96-well plate, where each well contains a unique barcoded primer (BC1). Perform in situ reverse transcription with random primers to generate cDNA tagged with the well-specific BC1 and a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) [14].

- Round-Two Indexing (Droplet-based): Pool all cells from the first-round plate. Load a suspension of up to 100,000 cells into a 10X Genomics Chromium controller to encapsulate single cells into droplets. Within the droplets, a second cell barcode (BC2) is ligated to the BC1-indexed cDNA molecules. The combination of BC1 and BC2 creates a unique cellular identifier for each cell [14].

Part 2: Library Preparation and rRNA Depletion

- Library Amplification: Break the droplets and recover the barcoded cDNA. Amplify the library via PCR to generate sufficient material for sequencing [14].

- rRNA Depletion (RNase H): Convert the amplified library to single-stranded RNA. Hybridize this RNA to DNA probes complementary to rRNA sequences. Add RNase H, which specifically cleaves the RNA in RNA:DNA hybrids, to digest ribosomal RNAs. The remaining rRNA-depleted library is then reverse-transcribed back into cDNA for sequencing [14]. This post-hoc depletion results in a dramatic increase in non-rRNA reads [14].

BacDrop Protocol

The BacDrop protocol integrates rRNA depletion earlier in the workflow, within the permeabilized cells [7].

- Cell Fixation and Permeabilization: Similar to M3-seq, cultures are fixed and permeabilized to make transcripts accessible [7].

- In-Cell rRNA Depletion: The permeabilized cells are incubated with rRNA-specific DNA probes and RNase H. This step digests rRNA in situ before the barcoding reactions, aiming to deplete ribosomal sequences at the source [7].

- Droplet-Based Barcoding and RT: The rRNA-depleted cells are co-encapsulated with barcoded gel beads in droplets using the 10X Chromium system. Within each droplet, cell lysis occurs, and the released mRNAs are barcoded during reverse transcription, assigning a unique cell barcode to all transcripts from a single cell [7].

- Library Construction: The barcoded cDNA is recovered, amplified, and prepared for sequencing following standard protocols [7].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logical relationship of these two main methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of M3-seq and BacDrop requires careful preparation and sourcing of key reagents. The table below details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for M3-seq and BacDrop

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fixative (e.g., Formaldehyde) | Preserves the transcriptional state of cells at the time of collection by crosslinking biomolecules. | Critical for preventing RNA degradation and maintaining cell integrity during permeabilization [14] [29]. |

| Permeabilization Cocktail (Lysozyme/Detergents) | Breaks down the bacterial cell wall to allow entry of barcoding primers and enzymes. | Must be optimized to allow access while preventing leakage of cellular contents [14] [29]. |

| Barcoded Primers & Oligos | Unique nucleotide sequences used to label all transcripts from a single cell. | The foundation of combinatorial indexing; requires careful design and quality control [14] [29]. |

| RNase H | Enzyme that degrades the RNA strand in an RNA-DNA hybrid. | Core to rRNA depletion in both M3-seq (post-library) and BacDrop (in-cell) [14] [7]. |

| Universal rRNA Probes | DNA oligonucleotides complementary to conserved rRNA sequences. | Used with RNase H to specifically target and deplete abundant rRNA [7]. |

| Poly(A) Polymerase (PAP) | Adds poly(A) tails to bacterial mRNAs. | Used in microSPLiT to enrich for mRNA over rRNA, as PAP favors mRNAs under specific conditions [29]. |

| 10X Genomics Chromium Controller & Kits | Microfluidic platform for generating nanoliter-scale droplets for single-cell barcoding. | Essential equipment for droplet-based methods like M3-seq and BacDrop; widely accessible [14] [7]. |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-propargyl | (S,R,S)-AHPC-propargyl, MF:C27H34N4O5S, MW:526.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Thalidomide-O-PEG2-Acid | Thalidomide-O-PEG2-Acid, MF:C20H22N2O9, MW:434.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Microbial Ecology and Pathogen Research

The application of M3-seq, BacDrop, and related technologies is yielding new insights into microbial life at single-cell resolution.

- Uncovering Bet-Hedging and Antibiotic Persistence: M3-seq has been used to reveal rare subpopulations of E. coli that employ bet-hedging strategies associated with stress responses. This heterogeneity is crucial for understanding how bacterial populations survive antibiotic treatment and other environmental challenges [14].

- Dissecting Phage-Host Interactions: Both M3-seq and microSPLiT have been applied to profile phage infection dynamics. M3-seq revealed independent prophage induction programs in Bacillus subtilis in response to DNA-damaging antibiotics, while microSPLiT has characterized infection heterogeneity in Bacteroides fragilis [14] [7].

- Profiling Complex Microbiomes: smRandom-seq, another droplet-based method, has demonstrated the ability to profile single-cell transcriptomes directly from human stool and bovine rumen microbiomes, opening the door to in situ functional studies of complex, native microbial communities [7].

- Characterizing Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs): BacDrop has been used to investigate the heterogeneous expression of MGEs and antibiotic response genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae, providing insights into the mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer and resistance gene dissemination [7].

M3-seq and BacDrop represent a paradigm shift in microbial ecology, moving beyond bulk population averages to explore the functional heterogeneity that underpins bacterial survival, adaptation, and interaction. Their ability to profile hundreds of thousands of cells in a single experiment makes it feasible to discover rare but critically important cell states, such as persisters, and to dissect complex interactions in phage infections and microbiome contexts. As these protocols continue to be refined and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly become standard tools for unraveling the intricate workings of microbial communities in health, disease, and the environment.

The field of microbial ecology has been revolutionized by single-cell sequencing technologies, which enable researchers to investigate the vast diversity of uncultivated microbial taxa and their functional roles within complex ecosystems [30]. Traditional metagenomic sequencing of entire environmental communities faces challenges in genome assembly and metabolic reconstruction of individual members, particularly in highly diverse systems [30]. Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represent complementary approaches that overcome these limitations by providing genomic and transcriptomic information at the fundamental unit of biology—the single cell [31] [32]. For microbial ecologists, these technologies offer unprecedented insights into the genetic potential and functional activities of individual microorganisms, revealing previously hidden heterogeneity and enabling the study of rare populations that may play critical ecological roles [14].

The integration of WGA and scRNA-seq provides a powerful framework for connecting genomic capacity with actual gene expression in single microbial cells, offering a more complete understanding of how microbial communities respond to environmental changes, interact with hosts, and perform ecosystem functions [30] [14]. This article details the experimental protocols and applications of these transformative technologies within the specific context of microbial ecology research.

Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) for Single-Cell Genomic Sequencing

Principles and Applications in Microbial Ecology

Whole Genome Amplification is a critical enabling technology for obtaining sufficient DNA for genomic sequencing from the minute amounts present in single microbial cells [32]. In microbial ecology, WGA has opened a window into the "microbial dark matter" of uncultivated taxa, allowing researchers to access genomic information from organisms that have not been grown in axenic culture [30]. The primary purpose of WGA is to non-selectively amplify the entire genome sequence from trace tissues and single cells, providing sufficient DNA template for comprehensive genome research without sequence bias [32]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse environmental samples, including soil bacteria, marine Crenarchaeota, Prochlorococcus, and candidate phyla like TM7 from soil and human oral cavity [30].

Key WGA Methodologies

Various WGA methods have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations for microbial ecological studies. These methods can be broadly categorized into PCR-based, isothermal amplification, and microfluidic amplification approaches [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Whole Genome Amplification Methods

| Method | Amplification Principle | Coverage Uniformity | Genome Completeness | Primary Applications in Microbial Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOP-PCR | PCR-based with degenerate oligonucleotide primers | Low due to exponential amplification bias | Low (∼70%) | Copy number variation analysis in large genome regions [32] |

| MDA | Isothermal amplification using phi29 polymerase | High due to linear amplification | High (often >70%) | Primary choice for uncultivated microbial species; generates high-molecular-weight DNA [30] [32] |

| MALBAC | Isothermal amplification with looping mechanism | Improved uniformity through quasi-linear pre-amplification | High | Single-cell sequencing of microbes with high GC content; reducing amplification bias [32] |

Detailed WGA Protocol for Single Microbial Cells

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Isolation

- Environmental Sample Processing: Begin by enriching microbial fractions from environmental samples (soil, water, air). For soil samples, employ density gradient centrifugation; for aquatic samples, use tangential filtration if biomass concentration is necessary [30].

- Single-Cell Isolation: Isolate individual microbial cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), micromanipulation, or microfluidic systems. FACS can process thousands of cells rapidly, while micromanipulation allows visual confirmation of single-cell capture and morphological observation [30].

- Cell Lysis: Transfer single cells to reaction vessels containing lysis buffer. Permeabilize microbial cells with lysozyme treatment to break down rigid cell walls [14].

DNA Amplification

- MDA Reaction Setup: For multiple displacement amplification, prepare reaction mixture containing:

- Phi29 DNA polymerase with high processivity and strand displacement capability

- Random hexamer primers

- dNTPs

- Reaction buffer